Abstract

Objective:

To determine whether simple diagnostic methods can yield relevant disease information in patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA).

Methods:

Patients with RA were randomly selected for inclusion in a cross-sectional study involving clinical evaluation of pulmonary function, including pulse oximetry (determination of SpO2, at rest), chest X-ray, and spirometry.

Results:

A total of 246 RA patients underwent complete assessments. Half of the patients in our sample reported a history of smoking. Spirometry was abnormal in 30% of the patients; the chest X-ray was abnormal in 45%; and the SpO2 was abnormal in 13%. Normal chest X-ray, spirometry, and SpO2 were observed simultaneously in only 41% of the RA patients. A history of smoking was associated with abnormal spirometry findings, including evidence of obstructive or restrictive lung disease, and with abnormal chest X-ray findings, as well as with an interstitial pattern on the chest X-ray. Comparing the patients in whom all test results were normal (n = 101) with those in whom abnormal test results were obtained (n = 145), we found a statistically significant difference between the two groups, in terms of age and smoking status. Notably, there were signs of airway disease in nearly half of the patients with minimal or no history of tobacco smoke exposure.

Conclusions:

Pulmonary involvement in RA can be identified through the use of a combination of diagnostic methods that are simple, safe, and inexpensive. Our results lead us to suggest that RA patients with signs of lung involvement should be screened for lung abnormalities, even if presenting with no respiratory symptoms.

Keywords: Arthritis, rheumatoid; Lung diseases, interstitial; Spirometry; Radiography, thoracic; Airway obstruction

Introduction

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a systemic inflammatory disorder with a 0.5-2% prevalence in the general population.1 Depending on the screening method used, up to 50% of patients exhibit pulmonary involvement. Nevertheless, the majority of cases have a subclinical presentation. (2,3) Recent studies have reported high mortality rates in patients with usual interstitial pneumonia, a severe form of interstitial lung disease (ILD).4 It has been proposed that patients with RA should be screened for ILD, through the use of chest X-rays and pulmonary function tests (PFTs).5 However, there is no consensus (mainly from the standpoint of methods or combinations of methods) regarding the appropriate screening of parenchymal lung disease in RA patients. Historically, studies evaluating chest X-rays in RA patients have detected abnormalities in only 1.6-6% of patients,6 8 whereas more recent studies have reported higher frequencies, ranging from 19% to 29%.3 9 The X-ray devices currently available offer better imaging evaluation, because of advanced image analysis tools and newer acquisition techniques, such as digital radiography,10 than do conventional devices.11

Although HRCT of the chest is more sensitive than is chest X-ray, the former detecting 50% of abnormalities,12 13 it is not recommended as a screening tool for pulmonary involvement in patients with RA, because the disease is highly prevalent and lung abnormalities in RA patients are often minimal.5 In a recent study involving 356 patients newly diagnosed with RA, Mori et al. found that only 15% had relevant abnormalities on HRCT scans,14 suggesting that HRCT should not be routinely performed after RA has been diagnosed.

Spirometry is an inexpensive, readily available tool for grading the severity of pulmonary impairment and can be applied on a large scale. Studies employing spirometry have detected abnormalities, mainly obstructive and restrictive patterns, in approximately 30% of patients with RA.1 Although low DLCO is a reliable early marker of pulmonary impairment,15 the diagnostic tool required in order to determine DLCO is not widely available.

We propose that a combination of clinical evaluations, including the use of pulse oximetry, chest X-ray, and spirometry, would provide accessible measurements that yield relevant disease information in patients with RA. Therefore, we performed a cross-sectional screening evaluation of a convenience sample of RA patients, in order to assess the prevalence of signs of lung disease in RA. We also evaluated the correlations among imaging abnormalities, PFT findings, clinical characteristics, SpO2, and smoking.

Methods

Study population

Between June 2009 and January 2011, patients with RA undergoing regular follow-up evaluations at the Rheumatoid Arthritis Clinic of the Rheumatology Department of the University of São Paulo School of Medicine Hospital das Clínicas, a tertiary care facility (teaching hospital) in the city of São Paulo, Brazil, were randomly referred for pulmonary evaluation. Patients were referred irrespective of respiratory symptoms or known lung disease. All of the referred patients had been diagnosed with RA on the basis of the criteria established in 1987 by the American College of Rheumatology.16 Patients were excluded if they were unable to perform spirometry maneuvers or did not complete the required tests.

Every referred patient met with the same pulmonologist, who gathered demographic and clinical data (age, gender, time from disease onset, occupational and/or environmental exposures and smoking status). Environmental exposures were defined as the presence of mold, birds, or feather bedding in the home, whereas occupational exposures were defined as the presence of toxic fumes or industrial dust in the work environment. Smoking status was characterized as "never smoker", "former smoker", or "current smoker". Smoking history (in pack-years) was also documented. On the basis of the various smoking-related outcomes,(17,18) tobacco smoke exposure (TSE) was classified as absent, low (< 10 pack-years), or high (≥ 10 pack-years).

The protocol for the research project was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Hospital das Clínicas and is in conformity with the guidelines established by the World Medical Association in the Declaration of Helsinki. All participating patients gave written informed consent.

Pulse oximetry

Using a pulse oximeter (Onyx Fingertip Pulse Oximeter, model 9500; Nonin Inc., Plymouth, MN, USA), we measured SpO2 (at rest, on room air) on the same day as the clinical evaluation. On the basis of the SpO2 values, patients were classified as presenting with "normal oxygenation" (SpO2 ≥ 95%), "mild hypoxemia" (SpO2 at 88-94%), or "severe hypoxemia" (SpO2 < 88%), the last being an indication for oxygen therapy.19

Clinical characteristics

Dyspnea was quantified based on the Medical Research Council dyspnea scale.20 This scale comprises five statements that describe nearly the entire range of respiratory disability, from no disability to almost complete incapacity.20 Patients classified as grades 1 or 2 are considered fit, those classified as grade 3 or 4 are considered to have moderate dyspnea, and those classified as grade 5 patients are considered to have severe dyspnea.21 Information on subcutaneous rheumatoid nodules, rheumatoid factor (RF), and antinuclear antibody (ANA) profile, as well as on the current and previous use of disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs and anti-inflammatory drugs, was retrieved by reviewing patient charts. In the statistical analyses, the anticipated potential confounders were subcutaneous rheumatoid nodules and Sjögren's syndrome.

Chest X-rays

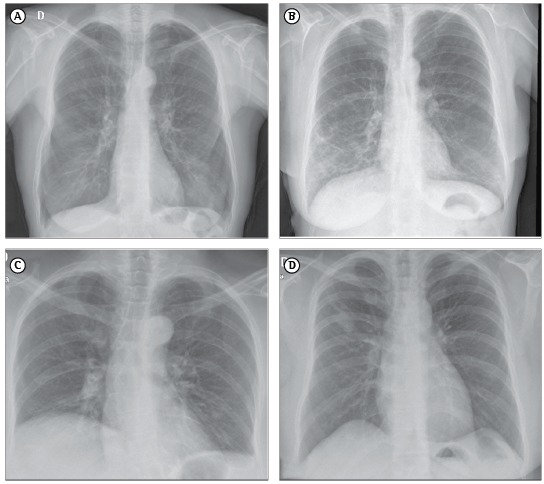

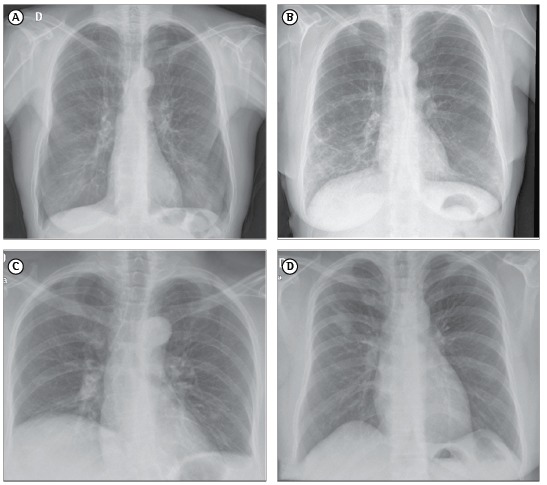

Chest X-rays were obtained with a digital radiography system employing a selenium detector. Images were acquired in posteroanterior and lateral views, at maximum inspiration. The chest X-ray images were analyzed independently by a pulmonologist and a radiologist, both of whom had experience in respiratory disorders. Although neither evaluator was blinded to the RA diagnosis, both were blinded to the clinical data. Disagreements were resolved by consensus, when possible. The evaluators assessed the presence of lung abnormalities using the following five-point confidence scale: 1 = definitely normal; 2 = most likely normal; 3 = equivocal; 4 = most likely abnormal; and 5 = definitely abnormal.22 Lungs were considered to be hyperinflated if any 2 of the following 3 criteria were met: diaphragm flattening; hemidiaphragm below the 10th posterior rib; and enlargement of the retrosternal space.23 Lung volume was considered to be diminished if the hemidiaphragm was above the 9th posterior rib.23 Parenchymal abnormalities were defined as the presence of an alveolar pattern; interstitial nodular opacities; interstitial reticular opacities; isolated lung nodule or mass; a likely calcified nodule; multiple nodules; cavitation; opacities from fibrotic scarring; lobar atelectasis; segmental atelectasis; or isolated hyperinflation.23 We also analyzed architectural distortions and signs of heart disease, such as cardiac or left atrial enlargement. The main profiles observed on the chest X-rays were hyperinflation, interstitial patterns, volume loss, and miscellaneous abnormalities (Figure 1). In patients with RA, hyperinflation and interstitial patterns are usually associated with pulmonary involvement caused by the RA itself, whereas volume loss and miscellaneous abnormalities are not.

Figure 1. Chest X-ray patterns: (A) hyperinflation; (B) interstitial, characterized by reticular or nodular opacities, bronchovascular or peripheral interstitial thickening, and architectural distortion; (C) volume loss, characterized by atelectasis or small lung size, without parenchymal abnormalities; and (D) miscellaneous abnormalities, defined as any lung abnormality not described above, such as nodules, masses, consolidation, and cavitation.

Pre- and post-bronchodilator spirometry

We performed pre- and post-bronchodilator spirometry with a KoKo spirometer (PFT; nSpire Health, Longmont, CO, USA), as described elsewhere.24 Predicted (reference) values were based on previous studies of the Brazilian population.25 The classification and grading of the results were based on the American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society guidelines26:

obstructive disease-defined as an FEV1/FVC ratio < lower limit of normal (LLN), with an FVC ≥ LLN (patients with an FEV1/FVC ratio < LLN and an FVC < LLN in the pre-bronchodilator tests but with normalization of FVC after reversibility testing also being included in this category)

possible restrictive disease-defined as an FEV1/FVC ratio ≥ LLN, with an FVC < LLN and no post-bronchodilator normalization of FVC

mixed disease-defined as an FEV1/FVC ratio < LLN, with an FVC < LLN, post-bronchodilator FVC < LLN and no bronchodilator reversibility

unclassified disease-defined as all other patterns

Statistical analysis

Continuous data are expressed as means or medians, with the observed ranges. Categorical data are expressed as percentages. Inter-rater agreement on the chest X-ray scores was assessed with the kappa statistic. Subgroup comparison was performed with an unpaired t-test for continuous variables with normal distribution or with the Wilcoxon rank-sum test when the assumption of normality was not met. We used the chi-square test (χ2 statistic) to examine independence between categorical variables, and we calculated the relative risk (RR), with its corresponding 95% confidence interval. Adjusted estimates were calculated with ANOVA. All reported values are two-sided and have not been adjusted for multiple comparisons. The Pearson product-moment correlation coefficient was used in order to measure the strength of the associations between parametric continuous variables. The level of statistical significance was set at p < 0.05. All statistical analyses were performed using OpenEpi (Open Source Epidemiologic Statistics for Public Health, Atlanta, GA, USA; http://www.openepi.com) and Stata, version 13 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA).

Results

Patient characteristics

Of the 975 patients actively being followed at the Rheumatoid Arthritis Clinic during the study period, 288 were submitted to initial evaluations. Of those 288 patients, 246 (86%) underwent complete assessments and were included in the final analysis. As can be seen in Table 1, the mean age was 56 ± 10 years, and 85% of the patients were female. The mean disease duration was 16 years. Eight patients (3.2%) had a history of pulmonary tuberculosis. Slightly more than half of the population reported smoking (48.8% were never smokers), and 14.1% reported high TSE. At enrollment in the study, 17.3% of the patients were current smokers (4% with low TSE and 13.3% with high TSE) and 33.7% were former smokers (12.6% with low TSE and 20.9% with high TSE). Of the 246 patients evaluated, 180 (73%) were RF-positive. Data related to ANAs were available for 172 patients, 85 (49.4%) of whom were ANA-positive. Although SpO2 was normal in the majority (86.6%) of the patients, mild hypoxemia was observed in 12.6% and severe hypoxemia (being an indication for oxygen therapy) was observed in 0.8%. On the basis of the Medical Research Council dyspnea scale score, most of the patients (82.1%) were categorized as fit.

Table 1. Comparison between rheumatoid arthritis patients with and without abnormalities on screening tests for lung abnormalities, adjusted for confounders (rheumatoid nodules and Sjögren's syndrome).a .

| Characteristic | No abnormalities | Any abnormalityb | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 101) | (n = 145) | ||

| Female | 89 (88) | 120 (82.8) | 0.007 |

| Age, years | 54.3 ± 10.4 | 58.0 ± 10.6 | 0.013 |

| RF-positive | 73 (72.3) | 107 (73.8) | 0.002 |

| Disease duration, years | 16.9 ± 10.7 | 16.2 ± 10.2 | 0.07 |

| Smoking status | |||

| Ever | 38 (37.6) | 88 (60.7) | < 0.0001 |

| Current | 10 (9.9) | 33 (22.8) | 0.0005 |

| Former | 28 (27.7) | 55 (37.9) | 0.086 |

| Exposures | |||

| Mold | 23 (22.8) | 31 (21.4) | 0.66 |

| Birds | 18 (17.8) | 23 (15.9) | 0.88 |

| Feather pillow | 12 (11.9) | 16 (11.0) | 0.80 |

| Occupational | 8 (7.9) | 21 (14.5) | 0.34 |

| Drugs | |||

| Methotrexate | 88 (87.1) | 138 (95.2) | 0.11 |

| Chloroquine | 83 (82.2) | 110 (75.9) | 0.35 |

| Leflunomide | 67 (66.3) | 104 (71.7) | 0.18 |

| Sulfasalazine | 48 (47.5) | 63 (43.4) | 0.47 |

| Azathioprine | 21 (20.8) | 36 (24.8) | 0.046 |

| Biologic | 37 (36.6) | 34 (23.4) | 0.18 |

| MRC dyspnea scale category | |||

| Fit | 85 (84.2) | 117 (80.7) | 0.24 |

| Moderate dyspnea | 16 (15.8) | 27 (18.6) | 0.23 |

| Severe dyspnea | 0 | 1 (0.7) | 0.80 |

RF: rheumatoid factor; and MRC: Medical Research Council. aValues expressed as n (%) or as mean ± SD. bOn any one of the three diagnostic tests applied (chest X-ray, spirometry, or pulse oximetry).

We stratified the patients by test results: those with normal chest X-ray, spirometry, and pulse oximetry findings (n = 101); and those with abnormalities on any of those tests (n = 145). When we compared those two groups, we found that significant abnormalities were more common in males, elderly patients, RF-positive patients, ever smokers (primarily current smokers), and patients with a history of azathioprine exposure (Table 1). In addition, we drew comparisons between the patients with no or low TSE and those with high TSE (Table 2). In all such comparisons, we adjusted for potential confounders.

Table 2. Comparison between rheumatoid arthritis patients with absent or low tobacco smoke exposure and those with high tobacco smoke exposure, adjusted for confounders (rheumatoid nodules and Sjögren's syndrome).a .

| Characteristic | Absent or low TSE | High TSE | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 161) | (n = 85) | ||

| Female | 138 (86) | 71 (83.5) | 0.50 |

| Age, years | 54.9 ± 11.2 | 59.5 ± 9.0 | 0.006 |

| RF-positive | 116 (72.0) | 64 (75.3) | 0.79 |

| Disease duration, years | 16.6 ± 10.3 | 16.3 ± 10.5 | |

| Abnormalities | |||

| On spirometry | 39 (24.2) | 35 (41.2) | 0.05 |

| On chest X-rays | 59 (36.6) | 51 (60.0) | < 0.001 |

| On pulse oximetry | 15 (9.3) | 18 (21.2) | 0.02 |

| Exposures | |||

| Mould | 34 (21.1) | 20 (23.5) | 0.39 |

| Birds | 29 (18.0) | 12 (14.1) | 0.56 |

| Feather pillow | 16 (9.9) | 12 (14.1) | 0.40 |

| Occupational | 16 (9.9) | 13 (15.3) | 0.15 |

| Drugs | |||

| Methotrexate | 145 (90.1) | 81 (95.3) | 0.11 |

| Chloroquine | 130 (80,8) | 63 (74.1) | 0.35 |

| Leflunomide | 114 (70.8) | 57 (67.1) | 0.26 |

| Sulfasalazine | 67 (41.6) | 44 (51.8) | 0.20 |

| Azathioprine | 34 (21.1) | 23 (27.1) | 0.54 |

| Biologic | 48 (29.8) | 23 (27.1) | 0.71 |

| MRC dyspnea scale category | |||

| Fit | 138 (85.7) | 64 (75.3) | 0.03 |

| Moderate dyspnea | 23 (14.3) | 20 (23.5) | 0.06 |

| Severe dyspnea | 0 | 1 (1.2) | - |

TSE: tobacco smoke exposure; RF: rheumatoid factor; and MRC: Medical Research Council. aValues expressed as n (%) or as mean ± SD.

Pre- and post-bronchodilator spirometry

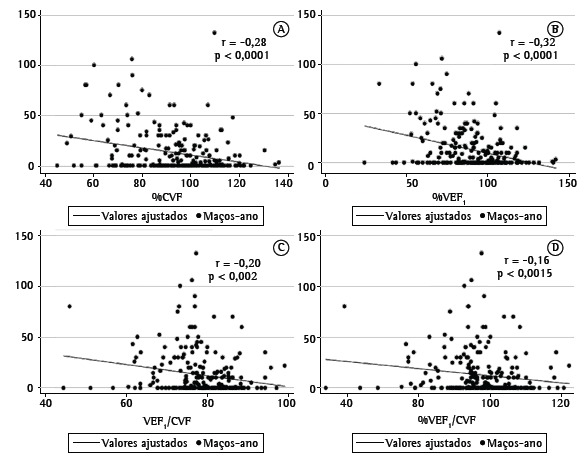

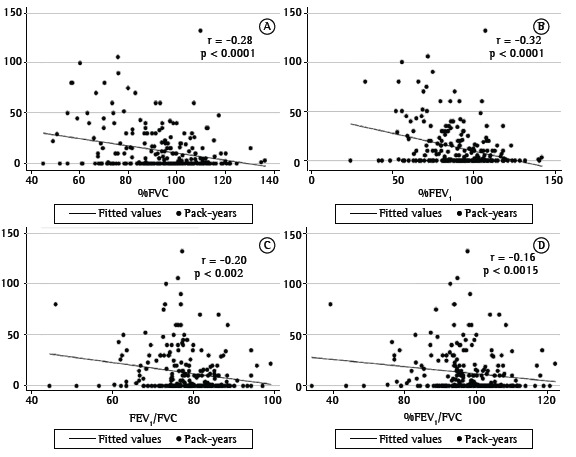

Spirometry was normal in 69.9% of the sample (Table 3). We observed obstructive and restrictive patterns in 11%; mixed patterns in 4.9%; and unclassified patterns in 2.8%. Typically, abnormal tests revealed mild severity. The cumulative TSE (pack-years) exhibited a statistically significant, albeit weak, negative correlation with percent-predicted FVC, percent-predicted FEV1, the percent-predicted FEV1/FVC ratio, and the absolute FEV1/FVC ratio (Figure 2).

Table 3. Spirometry characteristics.a .

| Spirometry findings | (n = 246) |

|---|---|

| Pattern | |

| Normal | 172 (69.9) |

| Obstructive | 28 (11.4) |

| Restrictive | 27 (11.0) |

| Mixed | 12 (4.9) |

| Unspecified | 7 (3) |

| Bronchodilator responsiveness | 24 (9.8) |

| Abnormalities | 74 (30.1) |

| Severity of abnormalitiesb | |

| Mild | 57 (77.0) |

| Moderate | 15 (20.3) |

| Severe | 2 (2.7) |

Values expressed as n (%). bn = 74.

Figure 2. Correlations between smoking history and spirometry parameters, showing that pack-years of smoking correlated negatively with percent-predicted FVC (A), percent-predicted FEV1 (B), the percent-predicted FEV1/FVC ratio (D), and the absolute FEV1/FVC ratio (C).

Chest X-rays

Chest X-rays were normal in 136 (55.3%) of the patients; hyperinflation was present in 61 (24.8%); the interstitial pattern was observed in 36 (14.6%); volume loss was observed in 6 (2.4%); and miscellaneous abnormalities were observed in the remaining 7 (2.8%). The inter-rater agreement was considered moderate (kappa = 0.4).

Combined methods

Only 41% of the patients had normal chest X-rays, normal spirometry findings, and normal SpO2 (Table 4). In 43.9% of the patients, chest X-rays and spirometry findings were normal. Abnormalities on chest X-rays alone were more common than were abnormalities on spirometry alone (26% vs. 11.4%). Because of parenchymal lesions or hyperinflation, 30% of the chest X-rays were classified as "definitely abnormal". Of the 61 patients with hyperinflation seen on the chest X-ray, 38 (62.3%) had normal spirometry findings, whereas spirometry showed an obstructive pattern in 16 (26.2%), a mixed pattern in 5 (8.2%), and a restrictive pattern in only 2 (3.3%). Among the 36 patients whose chest X-ray showed an interstitial pattern, the spirometry findings were normal in 18 (50.0%), showed a restrictive pattern in 11 (30.6%), showed a mixed pattern in 3 (8.3%), and showed an obstructive pattern in 2 (5.6%).

Table 4. Combined screening methods.a .

| Patient status | (N = 246) |

|---|---|

| Normal chest X-ray and normal spirometry | 108 (42.2) |

| Abnormal chest X-ray and normal spirometry | 64 (27.2) |

| Normal chest X-ray and abnormal spirometry | 28 (11.4) |

| Abnormal chest X-ray and abnormal spirometry | 46 (18.7) |

| Hyperinflation on chest X-ray | 61 (24.8) |

| Normal spirometry findingsb | 38 (62.3) |

| Obstructive pattern on spirometryb | 16 (26.2) |

| Restrictive pattern on spirometryb | 2 (3.3) |

| Interstitial pattern on chest X-ray | 36 (14.6) |

| Normal spirometry findingsc | 18 (50.0) |

| Restrictive pattern on spirometryc | 11 (30.6) |

| Obstructive pattern on spirometryc | 2 (5.6) |

| Any abnormalityd | 145 (58.9) |

Values expressed as n (%). bn = 61. cn = 36. dOn any one of the three diagnostic tests applied (chest X-ray, spirometry, or pulse oximetry).

When we analyzed dyspnea, we identified an association between a moderate to high level of dyspnea and a low SpO2 (p = 0.002; RR = 2.42; 95% CI: 1.39-4.20). However, we did not find dyspnea to be associated with abnormal findings on chest X-rays or spirometry.

High TSE showed significant positive associations with an obstructive pattern on spirometry (p = 0.02; RR = 2.18; 95% CI: 1.09-4.38), with a restrictive pattern on spirometry (p = 0.045; RR = 2.04; 95% CI: 1.005-4.139) and with abnormal spirometry findings in general (p = 0.006; RR = 1.70; 95% CI: 1.17-2.46). Nevertheless, 46.4% of the patients with obstructive spirometry patterns reported no or low TSE. High TSE was also positively associated with an interstitial pattern on chest X-rays (p = 0.01; RR = 2.12, 95% CI: 1.16-3.85) and with abnormal chest X-ray findings in general (p = 0.0005; RR = 1.63, 95% CI: 1.25-2.14). Although we identified no significant association between high TSE and hyperinflation seen on chest X-rays, 55.7% of the patients whose chest X-rays showed hyperinflation reported no or low TSE.

Discussion

We found that spirometry and chest X-rays frequently detected lung abnormalities in patients with RA, indicating that, given their feasibility and availability, these inexpensive screening tools should be incorporated into our practice as routine tests for RA patients. The combined analysis with the three diagnostic tools evaluated (chest X-ray, spirometry, and pulse oximetry) revealed abnormalities in 59% of the patients in our sample, suggesting that pulmonary involvement is prevalent and easily diagnosed in RA patients treated at a tertiary care hospital. Morrison et al. used chest X-rays and PFTs to evaluate 104 RA patients and reported abnormalities in 53.8%, mostly pleural disease (in 30%) and tuberculosis (in 44%).9 When patients with a smoking history or concomitant lung disease were excluded, the authors found abnormalities in 19.2% of the patients.

Cortet et al. compared PFTs and HRCT in screening for pulmonary involvement in 68 consecutive patients with RA.1 With spirometry, the authors detected lung abnormalities in 32% of the patients, observing obstructive patterns in 20% and a restrictive pattern in 12%. Using HRCT, the same authors detected lung abnormalities in 80.9% of the patients: bronchiectasis, in 30.5%; pulmonary nodules, in 28%; air trapping, in 25%; ground glass attenuation, in 17.1%; honeycombing, in 2.9%; and pleural effusion, in 1.5%. In our study, we observed abnormalities by spirometry in 30% of the patients (obstructive pattern in 11.4% and restrictive pattern in 11%), similar to the 32% reported in the Cortet et al. study.1 We also noted that lung abnormalities on chest X-rays were common (present in 45% of the patients), including hyperinflation (in 25%) and an interstitial pattern (in 15%). The differences in the frequencies observed on chest X-rays and those detected by HRCT might be attributed to the better sensitivity of HRCT in comparison with chest X-ray. A recent study conducted in Brazil reported HRCT lung abnormalities in 55% of 71 RA patients and found no correlation between lung disease and dyspnea,27 a result that is consistent with our findings and with those in the literature. Doyle et al. recently published slightly different results for RA patients who had been submitted to HRCT for respiratory symptom evaluation or cancer screening.28 Those authors observed statistically significant differences between patients with and without interstitial lung abnormalities, in terms of age, dyspnea, smoking, and spirometry findings. The significant difference in dyspnea might be explained by the inclusion criteria used by the authors. For example, HRCT of the chest was used only in patients in whom it was clinically indicated, which effectively excluded patients with asymptomatic ILD, thereby introducing a selection bias.

Our finding that dyspnea did not correlate with the abnormalities seen on spirometry or chest X-rays could be explained by subclinical abnormalities, given that most of the abnormalities seen on spirometry were mild and the prevalence of normal spirometry was high even when chest X-ray was abnormal. Another possibility is that patients with RA might be physically limited by the osteoarticular involvement. Our findings are consistent with those of a recent study by Mohd Noor et al.,29 who reported that, although 92% of the 63 RA patients evaluated exhibited no dyspnea, 95% and 71% of those patients, respectively, showed lung abnormalities on PFTs and HRCT. Therefore, in patients with RA, it is not advisable to wait until symptoms develop to perform the pulmonary evaluation.

Various risk factors have been associated with pulmonary involvement in RA, including male gender, advanced age, smoking, RF positivity, ANA positivity, and previous exposure to penicillamine or gold salts.7 28 30 31 In the present study, after adjusting for potential confounders, we found that the risk of pulmonary involvement in RA was higher in males, elderly patients, patients with a history of TSE (primarily current smoking), RF-positive patients, and patients with a history of exposure to azathioprine. These findings are consistent with those in the literature. It is possible that advanced patient age and longstanding TSE act synergistically to promote lung damage in patients with RA. It remains unclear whether disease duration is a risk factor for pulmonary involvement in RA.(27,30) In our study, there was no statistically significant between-group difference for disease duration. Azathioprine exposure has not previously been associated with pulmonary involvement in RA, and azathioprine is frequently prescribed to ILD patients in Brazil. Therefore, we believe that our finding (that azathioprine exposure increases the risk of pulmonary involvement in RA) represents a spurious association.

Other studies of patients with RA have demonstrated an association between smoking and airway disease,14 as well as between smoking and ILD.15 In the present study, we found a (weakly) significant negative correlation between TSE (pack-years) and pulmonary function, suggesting that smoking does in fact play a role in RA-associated lung disease. We also observed an association between high TSE and abnormalities on chest X-rays, although we found no association between high TSE and hyperinflation seen on chest X-rays. The majority of cases in which there was such hyperinflation were in never smokers or light smokers, as were approximately half of the cases in which spirometry showed an obstructive pattern. These results indicate that airway disease is common among RA patients and is not critically associated with TSE. Nevertheless, it is clear that TSE plays an important role in enhancing lung damage in RA. In our sample of RA patients, those with high TSE more often showed abnormalities on spirometry, chest X-rays, and pulse oximetry, and there was a negative correlation between TSE and pulmonary function parameters, as shown in Figure 2.

When analyzing post-bronchodilator spirometry findings, we observed that the group of patients who exhibited a positive response was not homogeneous, in terms of the diagnosis. In 11 patients, spirometry showed an obstructive pattern: 2 had asthma; 5 were suspected of having COPD; 3 had RA-associated lung disease; and 1 declined further evaluation. In 5 patients, spirometry showed a mixed pattern: 2 had hyperinflation and were suspected of having COPD; 1 had bronchiolitis; 1 had a history of pulmonary tuberculosis; and 1 had possible COPD and respiratory bronchiolitis-associated ILD. Eight patients had bronchial hyperresponsiveness. As can be seen, post-bronchodilator spirometry did not improve the differential diagnosis.

In the present study, most of the patients whose chest X-rays showed abnormalities exhibited normal spirometry findings. There are two possible explanations for that: the fact that mild lung involvement is common in patients with RA, as evidenced by the relative infrequency of hypoxemia in such patients; and the fact that some RA patients have airway and parenchymal lung disease, which could lead to normal spirometry findings. The latter might explain why spirometry findings can be normal in patients showing hyperinflation on chest X-rays, because mild interstitial abnormalities are not expected to be diagnosed by chest X-ray. We expected an obstructive pattern on spirometry to be uncommon among patients whose chest X-ray showed an interstitial pattern, just as we expected a restrictive pattern on spirometry to be an uncommon finding in patients whose chest X-ray showed hyperinflation.

Another interesting finding of the present study is that the prevalence of abnormalities on chest X-rays was 45%, which is much higher than the 1.6-6% previously described.(6-8) This might be attributed to a number of factors: selection bias, because our patients were invited by a physician to undergo lung screening; in our study, some chest X-rays might have been obtained at less than maximum inspiration; our method of chest X-ray evaluation, analyzing hyperinflation and categorizing the findings as "equivocal", "most likely abnormal", or "definitely abnormal", differed from that employed in other studies; and the possibly superior diagnostic performance of digital X-ray systems,22 which might provide better visualization of peripheral lung structures than do conventional X-ray systems.11 We believe that the two last factors represent the most likely explanations for the relatively high prevalence of abnormalities on chest X-rays in our study, given that the prevalence of abnormalities on spirometry was similar between our study and previous studies(12,32) and that the proportion of chest X-rays classified as "definitely abnormal" in our study (30%) is in fact consistent with the findings of more recent studies evaluating chest X-rays in RA patients.(3,9) Even if we excluded the volume loss pattern (caused by insufficient inspiration), our abnormality frequency would be 42.3%, well above what is expected. Zrour et al. evaluated chest X-rays in 75 RA patients and observed abnormalities in 29.3%.3 Given that we identified parenchymal abnormalities in 17.4% of our patients and lung volume abnormalities in 27.2%, we believe that the discrepancy between our findings and those of the authors cited above is attributable to the fact that we included hyperinflation in our analysis of the chest X-ray findings, as was not done in the Zrour et al. study.3 In the present study, inter-rater agreement was considered moderate, which was not entirely unexpected, because inter-rater differences in the classification of radiographs has long been known to be an inherent source of variation.33

Our study has some limitations. First, this cross-sectional study was based on a sample of patients treated at the rheumatology clinic of a tertiary care referral center. Therefore, it is likely that the patients recruited constituted a population with more advanced or difficult-to-treat disease, which could represent a selection bias. In addition, we did not evaluate the prevalence of crackles, although their importance as a marker for RA-associated ILD has previously been evaluated. 15 Furthermore, because we aimed to perform simple, objective, unbiased measurements, we did not perform echocardiograms. Therefore, chronic heart failure could have been misidentified as ILD. Moreover, because abnormalities were not evaluated by chest HRCT, our study might have underestimated the frequency of pulmonary involvement in RA patients, although our aim was to assess how simple diagnostic tests would perform in patients with RA. Finally, only 29.5% of the patients included in the initial evaluation were undergoing regular follow-up. However, because the invitation to participate in the study was random, we believe that our patient sample is representative of the target population.

In conclusion, RA is a common systemic inflammatory disorder and RA-associated lung disease is common. Studies have shown that pulmonary involvement is present in up to 50% of all patients with RA,(2,3) and the prevalence of RA in Brazil is 1%.34 This theoretical pulmonary involvement in up to 0.25-0.5% of the population likely consists of insignificant or mild abnormalities in the majority of patients. Given these observations, routine screening by HRCT scan and PFTs is not recommended,5 because the number of patients requiring such screening would be tremendous, making this strategy unfeasible. However, RA-associated pulmonary involvement is a source of substantial morbidity and mortality for affected patients,5 and disease progression has been described in approximately 60% of cases,15 which necessitates the implementation of an appropriate screening strategy.

We believe that asymptomatic patients with signs of lung involvement should undergo further investigation with HRCT and PFTs, including the measurement of DLCO and static lung volumes. Nevertheless, it is important to note that radiographic and PFT abnormalities might not lead to progressive disease in all cases.35

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Marianne Karel Verçosa Kawassaki and João Marcos Salge, for their vital technical assistance

Footnotes

Financial support: None.

Study carried out in the Divisão de Pneumologia, Instituto do Coração - InCor - Hospital das Clínicas, Faculdade de Medicina, Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo (SP) Brasil.

References

- 1.Cortet B, Perez T, Roux N, Flipo RM, Duquesnoy B, Delcambre B. Pulmonary function tests and high resolution computed tomography of the lungs in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 1997;56(10):596–600. doi: 10.1136/ard.56.10.596. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/ard.56.10.596 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cortet B, Flipo RM, Rémy-Jardin M, Coquerelle P, Duquesnoy B, Rêmy J. Use of high resolution computed tomography of the lungs in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 1995;54(10):815–819. doi: 10.1136/ard.54.10.815. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/ard.54.10.815 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zrour SH, Touzi M, Bejia I, Golli M, Rouatbi N, Sakly N. Correlations between high-resolution computed tomography of the chest and clinical function in patients with rheumatoid arthritis Prospective study in 75 patients. Joint Bone Spine. 2005;72(1):41–47. doi: 10.1016/j.jbspin.2004.02.001. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jbspin.2004.02.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kim EJ, Elicker BM, Maldonado F, Webb WR, Ryu JH, Van Uden JH. Usual interstitial pneumonia in rheumatoid arthritis-associated interstitial lung disease. Eur Respir J. 2010;35(6):1322–1328. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00092309. http://dx.doi.org/10.1183/09031936.00092309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim EJ, Collard HR, King TE., Jr Rheumatoid arthritis-associated interstitial lung disease the relevance of histopathologic and radiographic pattern. Chest. 2009;136(5):1397–1405. doi: 10.1378/chest.09-0444. http://dx.doi.org/10.1378/chest.09-0444 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stack BH, Grant IW. Rheumatoid interstitial lung disease. Br J Chest. 1965;59(4):202–211. doi: 10.1016/s0007-0971(65)80050-x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0007-0971(65)80050-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lamblin C, Bergoin C, Saelens T, Wallaert B. Interstitial lung diseases in collagen vascular diseases. Eur Respir J Suppl. 2001;32:69s–80s. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gabbay E, Tarala R, Will R, Carroll G, Adler B, Cameron D. Interstitial lung disease in recent onset rheumatoid arthritis. Pt 1Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1997;156(2):528–535. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.156.2.9609016. http://dx.doi.org/10.1164/ajrccm.156.2.9609016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Morrison SC, Mody GM, Benatar SR, Meyers OL. The lungs in rheumatoid arthritis--a clinical, radiographic and pulmonary function study. Afr Med J. 1996;86(7):829–833. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schaefer-Prokop C, Uffmann M, Eisenhuber E, Prokop M. Digital radiography of the chest detector techniques and performance parameters. J Thorac Imaging. 2003;18(3):124–137. doi: 10.1097/00005382-200307000-00002. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00005382-200307000-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ramli K, Abdullah BJ, Ng KH, Mahmud R, Hussain AF. Computed and conventional chest radiography a comparison of image quality and radiation dose. Australas Radiol. 2005;49(6):460–466. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1673.2005.01497.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-1673.2005.01497.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dawson JK, Fewins HE, Desmond J, Lynch MP, Graham DR. Fibrosing alveolitis in patients with rheumatoid arthritis as assessed by high resolution computed tomography, chest radiography, and pulmonary function tests. Thorax. 2001;56(8):622–627. doi: 10.1136/thorax.56.8.622. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/thorax.56.8.622 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Crestani B. The respiratory system in connective tissue disorders. Allergy. 2005;60(6):715–734. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2005.00761.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1398-9995.2005.00761.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mori S, Koga Y, Sugimoto M. Different risk factors between interstitial lung disease and airway disease in rheumatoid arthritis. Respir Med. 2012;106(11):1591–1599. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2012.07.006. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.rmed.2012.07.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gochuico BR, Avila NA, Chow CK, Novero LJ, Wu HP, Ren P. Progressive preclinical interstitial lung disease in rheumatoid arthritis. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168(2):159–166. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2007.59. http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/archinternmed.2007.59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Arnett FC, Edworthy SM, Bloch DA, McShane DJ, Fries JF, Cooper NS. The American Rheumatism Association 1987 revised criteria for the classification of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1988;31(3):315–324. doi: 10.1002/art.1780310302. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/art.1780310302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Calverley PM, Anderson JA, Celli B, Ferguson GT, Jenkins C, Jones PW. Salmeterol and fluticasone propionate and survival in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N Engl J Med. 2007;356(8):775–789. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa063070. http://dx.doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa063070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tashkin DP, Celli B, Senn S, Burkhart D, Kesten S, Menjoge S. A 4-year trial of tiotropium in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(15):1543–1554. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0805800. http://dx.doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa0805800 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease . Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease - Revised 2011. Bethesda: Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease; 2011. http://www.goldcopd.org/guidelines-global-strategy-for-diagnosis-management.html [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stenton C. The MRC breathlessness scale. Occup Med (Lond) 2008;58(3):226–227. doi: 10.1093/occmed/kqm162. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/occmed/kqm162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wedzicha JA, Bestall JC, Garrod R, Garnham R, Paul EA, Jones PW. Randomized controlled trial of pulmonary rehabilitation in severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients, stratified with the MRC dyspnoea scale. Eur Respir J. 1998;12(2):363–369. doi: 10.1183/09031936.98.12020363. http://dx.doi.org/10.1183/09031936.98.12020363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Garmer M, Hennigs SP, Jäger HJ, Schrick F, van de Loo T, Jacobs A. Digital radiography versus conventional radiography in chest imaging diagnostic performance of a large-area silicon flat-panel detector in a clinical CT-controlled study. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2000;174(1):75–80. doi: 10.2214/ajr.174.1.1740075. http://dx.doi.org/10.2214/ajr.174.1.1740075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Goodman LR, Felson B. Felson's principles of chest roentgenology. 3. Philadelphia: Saunders Elsevier; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miller MR, Hankinson J, Brusasco V, Burgos F, Casaburi R, Coates A. Standardisation of spirometry. Eur Respir J. 2005;26(2):319–338. doi: 10.1183/09031936.05.00034805. http://dx.doi.org/10.1183/09031936.05.00034805 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pereira CA, Sato T, Rodrigues SC. New reference values for forced spirometry in white adults in Brazil. J Bras Pneumol. 2007;33(4):397–406. doi: 10.1590/s1806-37132007000400008. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1806-37132007000400008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pellegrino R, Viegi G, Brusasco V, Crapo RO, Burgos F, Casaburi R. Interpretative strategies for lung function tests. Eur Respir J. 2005;26(5):948–968. doi: 10.1183/09031936.05.00035205. http://dx.doi.org/10.1183/09031936.05.00035205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Skare TL, Nakano I, Escuissiato DL, Batistetti R, Tde O Rodrigues, Silva MB. Pulmonary changes on high-resolution computed tomography of patients with rheumatoid arthritis and their association with clinical, demographic, serological and therapeutic variables. Rev Bras Reumatol. 2011;51(4):325–330. 336–337. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Doyle TJ, Dellaripa PF, Batra K, Frits ML, Iannaccone CK, Hatabu H. Functional impact of a spectrum of interstitial lung abnormalities in rheumatoid arthritis. Chest. 2014;146(1):41–50. doi: 10.1378/chest.13-1394. http://dx.doi.org/10.1378/chest.13-1394 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mohd Noor N, Mohd Shahrir MS, Shahid MS, Abdul Manap R, Shahizon Azura AM, Azhar Shah S. Clinical and high resolution computed tomography characteristics of patients with rheumatoid arthritis lung disease. Int J Rheum Dis. 2009;12(2):136–144. doi: 10.1111/j.1756-185X.2009.01376.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1756-185X.2009.01376.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mori S, Cho I, Koga Y, Sugimoto M. Comparison of pulmonary abnormalities on high-resolution computed tomography in patients with early versus longstanding rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2008;35(8):1513–1521. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Perez T, Remy-Jardin M, Cortet B. Airways involvement in rheumatoid arthritis clinical, functional, and HRCT findings. Pt 1Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1998;157(5):1658–1665. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.157.5.9710018. http://dx.doi.org/10.1164/ajrccm.157.5.9710018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vergnenègre A, Pugnere N, Antonini MT, Arnaud M, Melloni B, Treves R. Airway obstruction and rheumatoid arthritis. Eur Respir J. 1997;10(5):1072–1078. doi: 10.1183/09031936.97.10051072. http://dx.doi.org/10.1183/09031936.97.10051072 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Laney AS, Petsonk EL, Attfield MD. Intramodality and Intermodality Comparisons of Storage Phosphor Computed Radiography and Conventional Film-Screen Radiography in the Recognition of Small Pneumoconiotic Opacities. Chest. 2011;140(6):1574–1580. doi: 10.1378/chest.11-0629. http://dx.doi.org/10.1378/chest.11-0629 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mota LM, Cruz BA, Brenola CV, Pereira IA, Rezende-Fronza LS, Bertolo MB. Guidelines for the diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis. Rev Bras Reumatol. 2013;53(2):141–157. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Antin-Ozerkis D, Evans J, Rubinowitz A, Homer RJ, Matthay RA. Pulmonary manifestations of rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Chest Med. 2010;31(3):451–478. doi: 10.1016/j.ccm.2010.04.003. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ccm.2010.04.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]