Abstract

Objective:

To test the hypothesis that disease severity in patients with cystic fibrosis (CF) is correlated with an increased risk of sleep apnea.

Methods:

A total of 34 CF patients underwent clinical and functional evaluation, as well as portable polysomnography, spirometry, and determination of IL-1β levels.

Results:

Mean apnea-hypopnea index (AHI), SpO2 on room air, and Epworth Sleepiness Scale score were 4.8 ± 2.6, 95.9 ± 1.9%, and 7.6 ± 3.8 points, respectively. Of the 34 patients, 19 were well-nourished, 6 were at nutritional risk, and 9 were malnourished. In the multivariate model to predict the AHI, the following variables remained significant: nutritional status (β = −0.386; p = 0.014); SpO2 (β = −0.453; p = 0.005), and the Epworth Sleepiness Scale score (β = 0.429; p = 0.006). The model explained 51% of the variation in the AHI.

Conclusions:

The major determinants of sleep apnea were nutritional status, SpO2, and daytime sleepiness. This knowledge not only provides an opportunity to define the clinical risk of having sleep apnea but also creates an avenue for the treatment and prevention of the disease.

Keywords: Cystic fibrosis; Oxygenation; Sleep apnea, obstructive

Introduction

Hypoxemia is common in patients with advanced cystic fibrosis (CF), especially during rapid eye movement sleep.1 Although hypoxemia is more relevant in children than in adults, because the former have a longer rapid eye movement sleep duration than the latter,2 data on SpO2 in children with CF are scarce.3

In patients with CF, chronic alveolar hypoxia is the most likely cause of pulmonary hypertension, which worsens survival.4 In addition, CF patients experience decreased sleep efficiency,5 which affects their quality of life. Noninvasive ventilation improves alveolar ventilation, controlling hypercapnia and preventing episodes of desaturation during sleep.6

In a study of children with CF, 57% were found to have obstructive sleep apnea syndrome (OSAS).7 In a study of adults, the apnea-hypopnea index (AHI) was found to be similar between CF patients and healthy controls.8

Piper et al. showed significant associations between FEV1 and sleep disorders. It is known that FEV1 correlates positively with sleep duration and efficiency and negatively with the duration and number of awakenings.9

In patients with CF, OSAS might be associated with upper airway obstruction caused by chronic rhinosinusitis and nasal polyposis. In one study, CT confirmed the diagnosis of chronic rhinosinusitis in 93.54% of patients with CF.10

It is speculated that hypoxia affects the regulation of lung inflammation in patients with CF, activating cytokines, including IL-1β.11 The relationship of plasma inflammatory biomarkers with lung function and hospitalization history remains unexplored.12

The objective of the present study was to investigate symptoms and signs for predicting the AHI and sleep-disordered breathing in CF patients admitted for clinical treatment.

Methods

This was a cross-sectional study of consecutive patients with CF. We included 34 patients between 6 and 33 years of age with a diagnosis of CF based on at least two sweat tests showing chloride concentrations > 60 mEq/L, identification of two CF-associated mutations, or a combination of the two.13 Patients were recruited from among those admitted for clinical treatment at the Porto Alegre Hospital de Clínicas Referral Center, in the city of Porto Alegre, Brazil, between July of 2010 and September of 2012. Patients who used psychotropic substances were excluded, as were those with pulmonary decompensation requiring oxygen therapy, those who had been admitted for lung resection, those who were pregnant, and those who had undergone transplantation. The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Porto Alegre Hospital de Clínicas.

All of the patients who agreed to participate in the study underwent clinical and functional evaluation, as well as SpO2 measurement and evaluation with the Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS), during a clinically stable period. The body mass index (BMI) was calculated, and IL-1β levels were determined. The participants also underwent lung function assessment and portable polysomnography. In addition, CT scans were evaluated with the Lund-Mackay scoring system, and disease severity was assessed with the Shwachman-Kulczycki scoring system.

A pulse oximeter (SB220; Rossmax International Ltd, Taipei, Taiwan) was used in order to measure SpO2 on room air, with patients at rest in the 45° Fowler position. After 30 s of artifact-free reading and stabilization of the measured value (expressed in percentage), SpO2 was recorded.

Blood samples were collected between 10:00 a.m. and 12:00 p.m. for determination of IL-1β levels. The blood was centrifuged at 5,000 rpm for 5 min and transferred to microcentrifuge tubes, which were stored in a freezer at −80°C until the time of analysis (which was performed within 20 months after sample collection). Plasma levels of IL-1β were determined with a Human IL-1β TiterZyme(r) Enzyme Immunometric Assay Kit (Enzo Life Sciences, Inc., Farmingdale, NY, USA), in accordance with the manufacturer instructions, being expressed in pg/mL.

Nutritional assessment was performed by a nutritionist associated with the research team and was based on data regarding patient weight, height, and age. The method used in order to collect the aforementioned data has been described in detail elsewhere.14

For patients who were 19 years of age or younger, BMI and height-for-age percentiles were calculated, in accordance with the World Health Organization criteria.15 For those who were over 19 years of age, the BMI was calculated. Nutritional status was determined in accordance with Stallings et al.16 Children and adolescents with a BMI at or above the 50th percentile were considered well-nourished. Adult females with a BMI ≥ 22 kg/m2 and adult males with a BMI ≥ 23 kg/m2 were considered well-nourished.

The Lund-Mackay and Shwachman-Kulczycki scores17 were assessed by the attending pulmonologists and otolaryngologists. The Lund-Mackay score ranges from 0 to 24.18 In individuals under 12 years of age, in whom the sphenoid and frontal sinuses are either absent or underdeveloped, the maximum possible score is 16 rather than 24.

Portable polysomnography

Portable polysomnography was performed with a Somnocheck Effort device (Weinmann GmbH, Hamburg, Germany), which has a SCOPER categorization19 of 0,4,1×,2,4,2 and which has been validated at our institution.20 Airflow and snoring were evaluated by means of a nasal cannula connected to a pressure transducer; HR and SpO2 were measured by means of a pulse oximeter; thoracic movements were evaluated by means of a piezoelectric sensor; and body position was determined by means of a position sensor. Data were recorded from 11:00 p.m. to 7:00 a.m., being analyzed by a trained researcher.

The duration of apnea-hypopnea events was established at 5 s or more for individuals who were 12 years of age or younger and at 10 s or more for those who were over 12 years of age. Central events were defined by the absence of thoracic movement, whereas obstructive events were defined by the presence of respiratory effort. 21 The events were classified as apnea events when airflow was lower than 10% and as hypopnea events when there was a reduction of at least 50% in airflow accompanied by desaturation of 3%, autonomic arousal, or both, the latter being evidenced by an increase in HR (of 6 bpm or more).22

The AHI was calculated by dividing the total number of apnea and hypopnea events by the number of artifact-free hours of recording.21 Sleep apnea was defined as an AHI > 1 respiratory event per hour of sleep in children23 and as an AHI > 5 events/h in individuals over 12 years of age.22

ESS

The ESS is a self-report instrument that addresses the possibility of falling asleep in eight different situations, such as sitting in a car or watching television. The score for each item ranges from 0 (would never doze) to 3 (high chance of dozing). The total score ranges from 0 to 24; a score ≥ 10 indicates excessive daytime sleepiness.24 For patients under 12 years of age, we used the ESS revised for children.

Lung function

Spirometry was performed with a Jaeger-v4.31a spirometer (Jaeger, Würzburg, Germany). We measured FVC, FEV1, FEV1/FVC, and FEF25-75%. The tests were performed in accordance with the Brazilian Thoracic Association guidelines.25

Statistical analysis

Quantitative variables were expressed as mean and standard deviation or as median and interquartile range. Qualitative variables were expressed as absolute and relative frequencies. The Shapiro-Wilk test was used in order to determine the normality of continuous variables.

The Student's t-test was used in order to compare means, and Pearson's correlation test was used in order to assess the association between continuous variables. Multivariate linear regression analysis was used in order to control for confounding factors. Because of the small sample size, the only variables that were used as regressors were age, nutritional status, the ESS score, FEV1, and SpO2 on room air, in order to keep the models within the rules of parsimony. Variables without significance were removed from the model. Collinearity was studied in order to determine whether there was a correlation or association between regressors. The level of significance was set at 5% (p ≤ 0.05).

Results

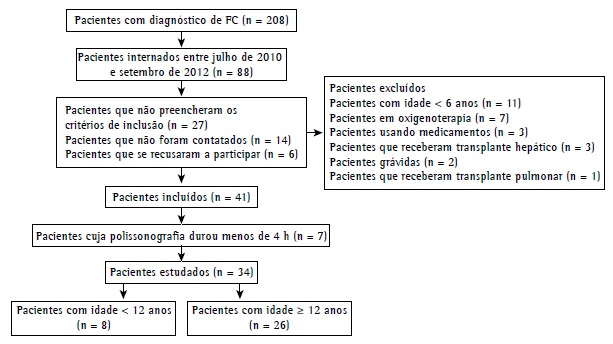

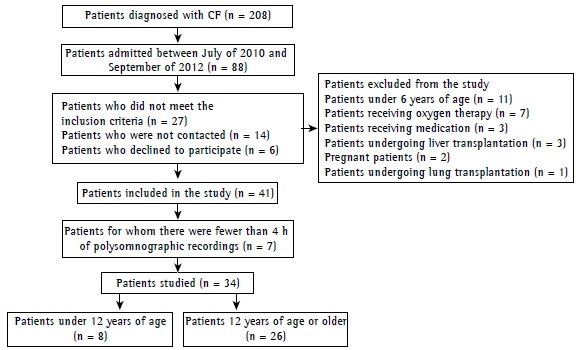

Between July of 2010 and September of 2012, a total of 88 patients were selected. After exclusions, losses, and declinations, 41 patients remained. There were fewer than 4 h of polysomnographic recordings for 7 of those patients, who were therefore excluded. The final sample consisted of 34 patients (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Flowchart of patient selection. CF: cystic fibrosis.

The mean age was 15.9 ± 7.0 years, and most of the patients were male. In addition, 8 were under 12 years of age, and 26 were 12 years of age or older. Mean post-bronchodilator FEV1 was 71 ± 31% of predicted, and mean SpO2 was 95.9 ± 1.9%. Of the sample as whole, 9 (26.47%) were malnourished, all of whom were children. Mean BMI was 18.3 ± 2.4 kg/m2 among the adults and 16.8 ± 2.1 kg/m2 among the children. The general characteristics of the patients are presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Characteristics of the study sample.a .

| Variable | (N = 34) |

|---|---|

| Age, years | 15.9 ± 7.0 (6-33) |

| Male/female, n/n | 20/14 |

| Age at diagnosis, yearsb | 1 (1-24) |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 18.3 ± 2.4 (14-23) |

| SpO2, % | 95.9 ±1.9 (92-99) |

| Mean SpO2, % | 94.8 ± 2.2 (89-97) |

| Minimum SpO2, % | 86.0 ± 4.9 (84-89) |

| Post-BD FEV1, % of predicted | 70.9 ± 30.9 (12-100) |

| IL-1β, pg/mL | 93.9 ± 41.9 (33-219) |

| AHI | 4.80 ± 2.60 (2.63-7.26) |

| Pediatric AHI | 4.93 ± 2.00 (2-8) |

| Adult AHI | 4.76 ± 2.80 (0.80-11) |

| S-K score | 72.5 ± 12.8 (40-100) |

| L-M score | 15.5 ± 5.0 (3-24) |

| ESS score | 7.6 ± 3.8 (0-16) |

| Nutritional status, % of cases | |

| Normal nutritional status | 19 |

| Nutritional risk | 6 |

| Malnutrition | 9 |

| Diabetes, % of cases | 4 |

BMI: body mass index; BD: bronchodilator; AHI: apnea-hypopnea index; S-K: Shwachman-Kulczycki; L-M: Lund-Mackay; and ESS: Epworth Sleepiness Scale. aValues expressed as mean ± SD (range), except where otherwise indicated. bValue expressed as median (interquartile range).

The AHI was found to correlate significantly with age and nutritional status (r = 0.379; p = 0.027 and r = −0.347; p = 0.04, respectively). Other correlations are shown in Table 2.

Table 2. Variables associated with the apnea-hypopnea index in the multivariate analysis.

| Variable | r | p |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 0.379 | 0.027* |

| Nutritional status | −0.347 | 0.044* |

| SpO2 | −0.188 | 0.288 |

| Mean SpO2 | −0.333 | 0.054 |

| Minimum SpO2 | −0.223 | 0.205 |

| Post-BD FEV1 | −0.060 | 0.736 |

| S-K score | 0.017 | 0.924 |

| L-M score | −0.173 | 0.336 |

| IL-1β | 0.130 | 0.535 |

| ESS score | 0.505 | 0.054 |

BD: bronchodilator; S-K: Shwachman-Kulczycki; L-M: Lund-Mackay; and ESS: Epworth Sleepiness Scale. *p < 0.05.

In the multiple linear regression model, age and FEV1 were collinear, the former therefore being excluded. Although SpO2 on room air was found to be less than significant, it remained in the analysis because of its clinical relevance.

Table 3 shows the results of the three variables that were included in the multivariate analysis; after adjustment, nutritional status (p = 0.014), the ESS score (p = 0.006), and SpO2 on room air (p = 0.005) remained significant. The model was able to explain 51% of the variation in the AHI (r2 = 0.51).

Table 3. Multiple linear regression.

| Variable | β | p |

|---|---|---|

| Nutritional risk | −0.386 | 0.014* |

| SpO2 | −0.453 | 0.005* |

| ESS score | 0.429 | 0.006* |

ESS: Epworth Sleepiness Scale. *p < 0.05.

Discussion

In the present study, we developed a model that was able to predict the AHI in patients with CF. Three easily obtainable clinical variables are useful in raising the suspicion of sleep apnea, a condition that can worsen the clinical picture of CF.

The study sample was selected at admission for routine treatment. During exacerbations of CF, sleep quality is impaired. By evaluating patients when their clinical status is at its best, on treatment day 12, approximately, we can avoid including cases in which sleep apnea-a long-term risk-is irrelevant in view of the immediate risk.

The high prevalence of OSAS in our pediatric patients is consistent with the findings of Amin et al., who compared CF patients with healthy controls.26 Given that nasal polyposis is one of the causes of OSAS,10 we evaluated the paranasal sinuses by means of sinus CT scans. However, we found no correlation between the Lund-Mackay score and the AHI.

Patients with OSAS and cough are prone to upper airway injury with epithelial damage and inflammation with neutrophil infiltration resulting from snoring and frequent episodes of airway obstruction.27 This might result in an increase in the soft tissues surrounding the oropharynx, reducing the upper airway diameter and changing the pattern of the air passage.28 However, we found no correlation between the AHI and cough or between the AHI and IL-1β.

In our study, a higher waking SpO2 on room air translated to a lower AHI. However, there was no correlation between FEV1 and the AHI. Likewise, Ramos et al. found no correlation between sleep disorders and lung disease severity.7

In a study by Perin et al.,8 waking SpO2 was similar to that in our study (95.1% vs. 95.9%). However, mean nocturnal SpO2 was different (92.0% vs. 94.8%). This is probably due to differences between the two samples in terms of their characteristics (adults only vs. adults and pediatric patients). In the study by Perin et al.,8 only 2 patients (3.9%) met polysomnographic criteria for the diagnosis of OSAS. This discrepancy is probably due to differences in evaluation methods between the two studies.

The data regarding the AHI in the present study are consistent with those in a study by Fauroux et al.,29 who evaluated adult and pediatric patients with CF. In that study, the BMI was 19 ± 2 kg/m2 among adults and 17 ± 2 kg/m2 among children; for the sample as a whole, the AHI was 4.3 ± 4.0 events/h.29 The adults in our sample had a BMI of 18.3 ± 2.4 kg/m2 and an AHI of 4.7 ± 2.8 events/h. Although FEV1 was lower in the patients in that study than in those in ours (41% vs. 70% of predicted), the nutritional status of the former group of patients was good. Sleepiness, as measured by the ESS score, was similar to that observed in our study (8.6 ± 3.4 vs. 7.6 ± 3.8).29

In 2008, Gregório et al. evaluated 38 children suspected of having sleep apnea.30 The AHI reported by those authors was quite similar to that which we found for the children in the present study (4.7 ± 2.8 vs. 4.9 ± 2.0). In that study, baseline SpO2 was 98 ± 0.8%, because patients with chronic lung disease were excluded from the sample.30 However, during sleep, minimum SpO2 was 84.3 ± 10.5%.30 Therefore, the severity of sleep apnea as measured by the AHI in the present study is consistent with that found in studies involving in-laboratory polysomnography.

Although obesity is a risk factor for OSAS,31 most children with CF are not obese. In our sample, 56% were well-nourished, 18% were at nutritional risk, and 26% were malnourished; a better nutritional status translated to a higher AHI, a finding that is consistent with the literature.

The present study has some limitations. First, the cross-sectional design does not allow us to determine the causal relationship between the independent variables studied and sleep apnea. As proof of concept rather than as a therapeutic indication, the use of continuous positive airway pressure would have allowed us to determine prospectively whether changes in nutritional status, sleepiness, and waking SpO2 on room air can be reversed by controlling sleep apnea. This, however, is beyond the scope of the present study. Second, we did not compare the group of CF patients with a control group. Obtaining a control group for studies involving patients with CF is a challenge that most studies cannot overcome. Studies involving patients with severe asthma might be a good model but are scarce in the literature. Third, the study sample was heterogeneous, including children and adults. However, in addition to allowing the use of age in the regression equations, our sample has the advantage of allowing assessment of a wide range of clinical presentations, given that CF progresses with age. Fourth, we did not perform an evaluation of tonsils and adenoids, using lateral neck X-rays and rhinoscopy.

In addition to the aforementioned limitations, it should be noted that sleep evaluation with portable polysomnography is unfeasible. The use of increased HR alone to detect awakenings might underestimate the AHI.22 A 3% decrease in SpO2 is a valid criterion for defining hypopnea in individuals without lung disease. The use of that criterion in individuals with CF might have overestimated the number of hypopnea events, given that SpO2 can decrease spontaneously, as a result of hypoventilation or local changes in the ventilation/perfusion ratio, without partial pharyngeal obstruction. Despite the aforementioned limitations, our results regarding the AHI are consistent with those of previous studies.

Another limitation of the present study is that portable polysomnography is associated with a high rate of losses. In our experience with patients under investigation for sleep apnea, fewer than 10% are lost; however, in the present study, 17% were lost. Of the recruited children, 33% were lost; that is, 4 of 12 volunteers were lost. Of the adults, only 3 removed the cannula, the oximeter, or both because of discomfort. This suggests that portable polysomnography should not be used in studies involving individuals under 12 years of age.

The small sample size limits the number of variables that can be used in a multivariate model. For a sample size of 34, no more than three variables can be used. Binary logistic regression models, which predict the presence or absence of sleep apnea, could provide immediately useful information. It would be of interest to clinicians to know the odds ratio for each of the findings in individuals suspected of having sleep apnea. We attempted to define critical values using a ROC curve, and we tested various binary logistic regression models. However, the models proved unstable, and no independent variable was significant. This is probably due to the loss of information that inevitably occurs when continuous variables are transformed into binary variables (even more so with only 34 cases).

In conclusion, the results of the present study show that, in patients with CF, the clinical findings most closely associated with the risk of sleep apnea are nutritional status, waking SpO2 on room air, and sleepiness. This model explains 51% of the variation in the AHI and provides clinicians with an opportunity to predict cases of significant sleep apnea.

Footnotes

Financial support: This study received financial support from the Fundo de Incentivo a Pesquisa e Eventos do Hospital de Clínicas de Porto Alegre (FIPE/HCPA, Fund for the Incentive of Research and Events of the Porto Alegre Hospital de Clínicas).

Study carried out at the Hospital de Clínicas de Porto Alegre, Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul, Porto Alegre (RS) Brasil.

References

- 1.Muller NL, Francis PW, Gurwitz D, Levison H, Bryan AC. Mechanism of hemoglobin desaturation during rapid-eye-movement sleep in normal subjects and in patients with cystic fibrosis. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1980;121(3):463–469. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1980.121.3.463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marcus CL. Sleep-disordered breathing in children. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;164(1):16–30. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.164.1.2008171. http://dx.doi.org/10.1164/ajrccm.164.1.2008171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.van der Giessen L, Bakker M, Joosten K, Hop W, Tiddens H. Nocturnal oxygen saturation in children with stable cystic fibrosis. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2012;47(11):1123–1130. doi: 10.1002/ppul.22537. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/ppul.22537 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tonelli AR. Pulmonary hypertension survival effects and treatment options in cystic fibrosis. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2013;19(6):652–661. doi: 10.1097/MCP.0b013e3283659e9f. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/MCP.0b013e3283659e9f [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dancey DR, Tullis ED, Heslegrave R, Thornley K, Hanly PJ. Sleep quality and daytime function in adults with cystic fibrosis and severe lung disease. Eur Respir J. 2002;19(3):504–510. doi: 10.1183/09031936.02.00088702. http://dx.doi.org/10.1183/09031936.02.00088702 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Milross MA, Piper AJ, Norman M, Becker HF, Willson GN, Grunstein RR. Low-flow oxygen and bilevel ventilatory support effects on ventilation during sleep in cystic fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;163(1):129–134. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.163.1.2005130. http://dx.doi.org/10.1164/ajrccm.163.1.2005130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ramos RT, Salles C, Daltro CH, Santana MA, Gregório PB, Acosta AX. Sleep architecture and polysomnographic respiratory profile of children and adolescents with cystic fibrosis. J Pediatr (Rio J) 2011;87(1):63–69. doi: 10.2223/JPED.2055. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0021-75572011000100011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Perin C, Fagondes SC, Casarotto FC, Pinotti AF, Menna Barreto SS, Dalcin Pde T. Sleep findings and predictors of sleep desaturation in adult cystic fibrosis patients. Sleep Breath. 2012;16(4):1041–1048. doi: 10.1007/s11325-011-0599-5. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11325-011-0599-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Piper AJ, Bye PT, Grunstein RR. Sleep and breathing in cystic fibrosis. Sleep Med Clin. 2007;2:87–97. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2004.03.004. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jsmc.2006.11.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boari L, de NP., Castro Júnior Diagnosis of chronic rhinosinusitis in patients with cystic fibrosis: correlation between anamnesis, nasal endoscopy and computed tomography. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol. 2005;71(6):705–710. doi: 10.1016/S1808-8694(15)31236-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Krueger JM, Rector DM, Churchill L. Sleep and cytokines. Sleep Med Clin. 2007;2(2):161–169. doi: 10.1016/j.jsmc.2007.03.003. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jsmc.2007.03.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ngan DA, Wilcox PG, Aldaabil M, Li Y, Leipsic JA, Sin DD. The relationship of systemic inflammation to prior hospitalization in adult patients with cystic fibrosis. BMC Pulm Med. 2012;12:3–3. doi: 10.1186/1471-2466-12-3. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1471-2466-12-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.O'Sullivan BP, Freedman SD. Cystic fibrosis. Lancet. 2009;373(9678):1891–1904. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60327-5. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60327-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pereira JS, Forte GC, Simon MI, Drehmer M, Behling EB. Perfil nutricional de pacientes com fibrose cística em um centro de referência no sul do Brasil. Clin Biomed Res (P Alegre) 2011;31(2):131–137. [Google Scholar]

- 15.World Health Organization . The WHO Child Growth Standards. The WHO Child Growth Standards. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2014. http://www.who.int/childgrowth/ [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stallings VA, Stark LJ, Robinson KA, Feranchak AP, Quinton H. Clinical Practice Guidelines on Growth and Nutrition Subcommittee Evidence-based practice recommendations for nutrition-related management of children and adults with cystic fibrosis and pancreatic insufficiency results of a systematic review. J Am Diet Assoc. 2008;108(5):832–839. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2008.02.020. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jada.2008.02.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.h Shwachman, ll kulczycki. Long-term study of one hundred five patients with cystic fibrosis; studies made over a five- to fourteen-year period. AMA J Dis Child. 1958;96(1):6–15. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1958.02060060008002. http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/archpedi.1958.02060060008002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lund VJ, Mackay IS. Staging in rhinosinusitis. Rhinology. 1993;31(4):183–184. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Collop NA, Tracy SL, Kapur V, Mehra R, Kuhlmann D, Fleishman SA. Obstructive sleep apnea devices for out-of-center (OOC) testing technology evaluation. J Clin Sleep Med. 2011;7(5):531–548. doi: 10.5664/JCSM.1328. http://dx.doi.org/10.5664/jcsm.1328 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tonelli de Oliveira AC, Martinez D, Vasconcelos LF, Gonçalves SC, Lenz MC, Fuchs SC. Diagnosis of obstructive sleep apnea syndrome and its outcomes with home portable monitoring. Chest. 2009;135(2):330–336. doi: 10.1378/chest.08-1859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Iber C, Ancoli-Israel S, Chesson A, Jr, Quan S. The AASM Manual for the scoring of sleep and associated events:rules, terminology and technical specifications. Westchester, IL: American Academy of Sleep Medicine; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ayappa I, Rapaport BS, Norman RG, Rapoport DM. Immediate consequences of respiratory events in sleep disordered breathing. Sleep Med. 2005;6(2):123–130. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2004.08.005. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.sleep.2004.08.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kuhle S, Urschitz MS, Eitner S, Poets CF. Interventions for obstructive sleep apnea in children a systematic review. Sleep Med Rev. 2009;13(2):123–131. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2008.07.006. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.smrv.2008.07.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Johns MW. A new method for measuring daytime sleepiness the Epworth sleepiness scale. Sleep. 1991;14(6):540–545. doi: 10.1093/sleep/14.6.540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sociedade Brasileira de Pneumologia e Tisiologia Diretrizes para Testes de Função Pulmonar. J Pneumol. 2002;28(Suppl 3):S1–S238. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Amin R, Bean J, Burklow K, Jeffries J. The relationship between sleep disturbance and pulmonary function in stable pediatric cystic fibrosis patients. Chest . 2005;128(3):1357–1363. doi: 10.1378/chest.128.3.1357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Birring SS, Ing AJ, Chan K, Cossa G, Matos S, Morgan MD. Obstructive sleep apnoea a cause of chronic cough. Cough. 2007;3:7–7. doi: 10.1186/1745-9974-3-7. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1745-9974-3-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mello CF, Junior, Guimarães HA, Filho, Gomes CA, Paiva CC. Radiological findings in patients with obstructive sleep apnea. J Bras Pneumol. 2013;39(1):98–101. doi: 10.1590/S1806-37132013000100014. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1806-37132013000100014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fauroux B, Pepin JL, Boelle PY, Cracowski C, Murris-Espin M, Nove-Josserand R. Sleep quality and nocturnal hypoxaemia and hypercapnia in children and young adults with cystic fibrosis. Arch Dis Child. 2012;97(11):960–966. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2011-300440. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/archdischild-2011-300440 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gregório PB, Athanazio RA, Bitencourt AG, Neves FB, Terse R, Hora F. Symptoms of obstructive sleep apnea-hypopnea syndrome in children. J Bras Pneumol. 2008;34(6):356–361. doi: 10.1590/s1806-37132008000600004. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1806-37132008000600004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tauman R, Ivanenko A, O'Brien LM, Gozal D. Plasma C-reactive protein levels among children with sleep-disordered breathing. Pediatrics. 2004;113(6):e564–e569. doi: 10.1542/peds.113.6.e564. http://dx.doi.org/10.1542/peds.113.6.e564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]