Abstract

For early-stage lung cancer, the treatment of choice is surgery. In patients who are not surgical candidates or are unwilling to undergo surgery, radiotherapy is the principal treatment option. Here, we review stereotactic body radiotherapy, a technique that has produced quite promising results in such patients and should be the treatment of choice, if available. We also present the major indications, technical aspects, results, and special situations related to the technique.

Keywords: Radiation oncology, Lung neoplasms/radiotherapy, Lung neoplasms/surgery, Respiratory function tests

Introduction

Lung cancer is the most common type of cancer in males and females worldwide, accounting for the highest number of cancer deaths.1 This is probably due to the fact that many lung cancer patients are diagnosed at advanced stages. Patients who are diagnosed at early stages can undergo surgical resection and account for 20-25% of cases. However, 20-30% of such patients are not surgical candidates or are unwilling to undergo surgery.2 Median survival is 13 months for patients with untreated T1 tumors and 8 months for those with untreated T2 tumors, the 5-year cancer-specific survival rate being 16%.3 Therefore, a therapeutic intervention is warranted in this group of inoperable patients, radiation therapy being the traditional alternative.

Conventional radiation therapy involves fractionated radiation doses of 1.8-2.0 Gy/day for a total radiation dose of 60-70 Gy, corresponding to more than six weeks of treatment. Various techniques can be used, ranging from simple, two-dimensional techniques to sophisticated techniques such as three-dimensional radiation therapy and intensity-modulated radiation therapy. However, in patients with stage I lung cancer, the results of conventional radiation therapy are markedly inferior to those of surgery, with local recurrence rates of up to 70%.(4-6)

In an attempt to improve the results, dose escalation studies involving conventional fractionation have been conducted and have generally involved patients with locally advanced disease, showing controversial results regarding the benefits of dose escalation; however, the results regarding increased toxicity have been consistent.(7-9) For the treatment of early-stage lung cancer, another strategy is to combine stereotactic localization techniques with high-dose hypofractionation, and this strategy is the focus of the present review. In general, 1-5 fractions are delivered in a period of less than two weeks.

Initially employed in the treatment of central nervous system tumors, in which context it is popularly known as radiosurgery, stereotactic radiation therapy has yielded promising results since it was first described in 199510 and, in recent years, has been considered the treatment of choice for medically inoperable patients with early-stage non-small cell lung carcinoma (NSCLC).11

Although a variety of terms are used in order to describe stereotactic radiation therapy, the principle remains the same. In North America, it is commonly referred to as stereotactic body radiotherapy (SBRT), whereas in Europe it is known as stereotactic ablative radiotherapy. The term radiosurgery continues to be used, especially by patients and the media.

Biological aspects of high-dose radiation therapy

A key feature of stereotactic radiation therapy is the use of ablative doses of radiation delivered in few fractions and recognized by a biological equivalent dose (BED) > 100 Gy. A mathematical formalism, BED takes into account the radiation dose per fraction, the number of fractions, the total duration of treatment, and the radiosensitivity of tissues. It is used in order to calculate biologically equivalent doses between different fractionation schedules, given that the nominal total dose does not completely reflect the biological effects of radiation therapy on a tumor.

In addition to causing direct and indirect cell damage, delivery of ablative doses of radiation to neoplastic lesions prevents tumor repopulation. Furthermore, ablative radiation therapy causes vascular damage, which results in endothelial apoptosis and remodeling of the microvasculature and probably induces an immune response against the tumor as a result of the use of high radiation doses per fraction.12

In cases in which SBRT is delivered to lung lesions, local control rates are related to the BED employed. In a secondary analysis of retrospective studies examining the clinical implications of SBRT, local control and survival rates were found to be higher when BED was high (≥ 100 Gy10) than when BED was < 100 Gy10.(13,14)

Technical aspects of SBRT

According to Timmerman et al.,15 the toxicity of ablative doses of radiation is related to doses within a radius of 0-3 cm around the edges of the target volume. One can thus imagine a "shell" surrounding the tumor and constituting the volume of damaged normal tissue, which will eventually result in toxicity. Therefore, low rates of SBRT-related toxicity essentially depend on reducing the volume of this shell. This can be achieved with high-dose conformal radiation around the target and a rapid decrease in dose levels around it (defined as high dose gradient).

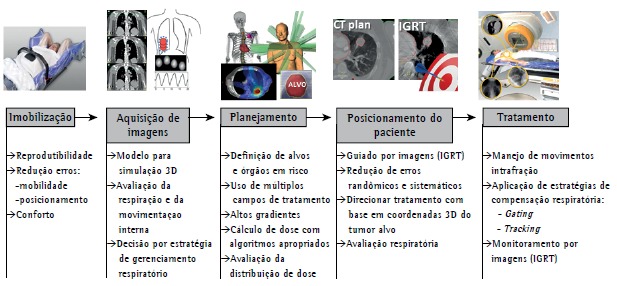

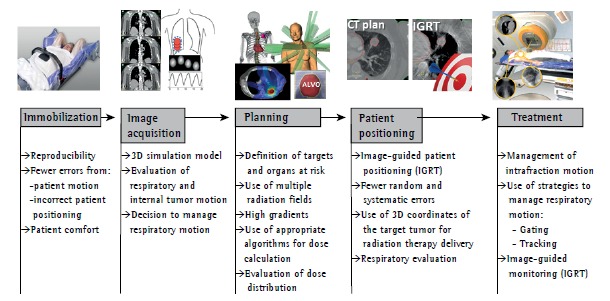

The use of SBRT requires a high level of accuracy throughout the treatment process. Such accuracy is achieved through the integration of modern imaging, simulation, planning, and dose delivery technologies and is maintained during treatment delivery (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Description of the steps involved in stereotactic body radiation therapy. IGRT: image-guided radiotherapy.

The process begins with the production of an immobilization device aimed at minimizing patient motion during treatment (intrafraction motion). In addition to minimizing intrafraction motion, immobilization aids in reproducing patient positioning throughout the treatment period (interfraction motion).

The next step is the acquisition of a CT image with the patient in the treatment position. The CT image is used in order to create a three-dimensional model on which radiation therapy planning will be based. At this stage of the process, internal tumor motion caused by breathing should be evaluated in order to define the margin of treatment field.

Tumor motion can be studied by four-dimensional CT imaging, which is the current gold standard. However, serial CT imaging can also be used.

If target motion amplitude is large, the inclusion of the entire region in the treatment volume might result in exceedingly high rates of SBRT-related toxicity. Therefore, a decision can be made to manage respiratory motion. Techniques to manage respiratory motion include abdominal compression, synchronization of radiation delivery with a particular stage of the respiratory cycle (gating), and moving the radiation beam so as to follow the tumor motion trajectory in real time (tracking).

During planning, multiple radiation fields and a highly conformal dose distribution around the target volume are obtained after the targets have been defined, and specific objectives are established by protocols such as Radiation Therapy Oncology Group (RTOG) 023616 and RTOG 0813,17 by means of which these objectives are evaluated, the tolerance of neighboring organs being taken into account.

Three-dimensional coordinates of the target tumor are used in order to position patients for radiation therapy delivery (stereotactic concept). This is achieved with the use of image-guided radiation therapy techniques that allow visualization of the tumor or of markers implanted during treatment. This technology allows a significant reduction in geometric errors that are inherent to conventional radiation therapy and are related to patient positioning.

SBRT can be performed with linear accelerators, with tools that allow monitoring of target motion, or with systems specifically designed for it, such as CyberKnife(r) (Accuray Inc., Sunnyvale, CA, USA), all of which yield similar results.

Current indications for SBRT and outcomes

Stage I or II NSCLC patients, who have no lymph node involvement and who are medically inoperable, constitute the target population for SBRT. Although there have been reports of SBRT in patients with tumors of up to 10 cm in diameter, mean tumor diameter is 3 cm, and consensus dictates that patients with lesions ≤ 5 cm in diameter can be treated with SBRT. Cases of tumor recurrence and metastatic lesions can also be treated with SBRT.13

Initially, the most relevant studies evaluating the use of SBRT in patients with lung lesions (early-stage NSCLC) examined the treatment of central and peripheral lesions. However, adverse event profiles were found to be different across studies, and the data constituted evidence for the use of SBRT in patients with peripheral lesions.(18-20)

Peripheral lesions

Several retrospective studies have shown local control rates > 80% and a low toxicity profile in patients with small (T1 and T2) peripheral tumors (Table 1).(18,21-26)

Table 1. Studies reporting clinical outcomes in patients with central or peripheral lung lesions treated with stereotactic body radiation therapy.

| Study | Number of patients | Dose | Central or peripheral lesion | Local control | Complications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Onishi et al.21 | 257 | 1-14 fractions (30-84 Gy) | both | 84% (5 years) BED ≥ 100 Gy | ≥ grade 3: pulmonary complications, in 5.4%; esophageal complications, in 1.0%; dermatitis, in 1.2% |

| Nagata et al.22 | 104 | 4 × 12 Gy | both | 3-year progression-free survival, 69% | grade 3: dyspnea, in 9%; pneumonitis, in 7%; intercostal pain, in 2%; cough, in 1% grade 4: dyspnea, in 1% |

| Baumann et al.23 | 57 | 3 × 15 Gy | peripheral | 92% (3 years) | grade 3: 28% grade 4: 1.7% |

| Senthi et al.24 | 676 | 3-8 fractions (54-60 Gy) | both | 89% (5 years) | - |

| Timmerman et al.18 | 70 | 3 × 20-22 Gy | both | 95% (2 years) | pneumonitis, in 6%; rib fractures, in 3% |

| Brown et al.25 | 59 | 1-5 fractions (15.0-67.5 Gy) | both | disease-free survival, 90% | grade 3: pneumonitis, in 7% |

| Van der Voort et al.26 | 70 | 3 × 12-15 Gy | peripheral | 96% (2 years if dose was = 60 Gy) | late toxicity, in 10% |

BED: biological equivalent dose.

In RTOG 0236 (a multicenter phase II study), 52 patients with medically inoperable T1-3 NSCLC (< 5 cm) were treated with 60 Gy delivered in 3 fractions. Long-term results showed a disease-free survival of 26% and an overall survival of 40% after a median follow-up of 4 years. In addition, only 7% of the patients had primary tumor recurrence; however, 13% experienced locoregional recurrence at 3 years. Grade 3 toxicity was reported in 15 patients, and grade 4 toxicity was reported in 2, with no reports of grade 5 toxicity.27

In another study (RTOG 0618), 33 operable patients with T1-3N0 NSCLC were also treated with 60 Gy delivered in 3 fractions. The 2-year local failure rate was 8%.28

An interesting observational study conducted in the Netherlands showed that the introduction of SBRT for the elderly increased survival in inoperable stage I NSCLC patients when compared with historical groups of untreated patients. 29 In patients with peripheral lesions, there is an increased risk of chest wall toxicity, which manifests as pain or rib fracture.30 In patients with apical lesions, there is an increased risk of brachial plexopathy.31 A better understanding of tolerance and dose limits has led to a decrease in the risk of chest wall pain and rib fracture.32

Central lesions

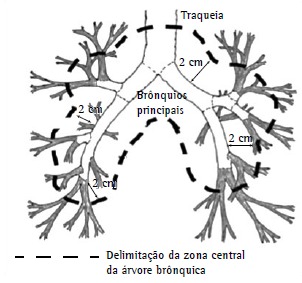

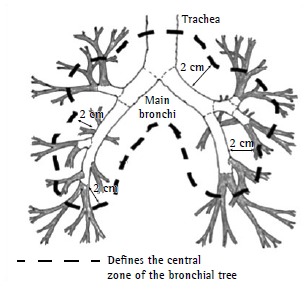

The use of SBRT to treat patients with central lung lesions (Figure 2) began to be questioned after the publication of results showing severe toxicity rates of 17% and 46% at 3 years for peripheral and central lesions, respectively, 6 deaths having been related to the treatment of central lesions.(33,34)

Figure 2. Definition of central zone: region within a radius of 2 cm around the proximal bronchial tree (within the dashed line). Adapted from the Radiation Therapy Oncology Group.16 .

Because of the aforementioned results, it was suggested that it would be safer and more appropriate to use a larger number of fractions (5 or more fractions) and smaller doses per fraction to treat patients with central lesions. It was recommended that the dose limits for adjacent organs and normal structures be rigorously evaluated and that imaging methods that are more consistent be used in order to evaluate tumors and tumor motion during breathing.35

In studies conducted more recently, central lesions were evaluated separately, and the incidence of toxicity was reported to be low, with excellent clinical outcomes (Table 2).(36-42)

Table 2. Clinical outcomes of stereotactic body radiation therapy in central lesions.

| Study | Number of patients | Tumor | Dose | Local control | Survival |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Haasbeek et al.36 | 63 | NSCLC (T1-3N0M0) | 60 Gy (8 fxs) | 92.6% (5 years) | DFS: 71% OS: 49.5% (5 years) |

| Nuyttens et al.37 | 56 | NSCLC: 69.6%; metastatic NSCLC: 30.4% | 45-60 Gy (5 fxs); 48 Gy (6 fxs) | 76% (2 years) | CSS: 80% (3 years) OS: 60% (2 years) |

| Rowe et al.38 | 47 | NSCLC: 59%; metastatic NSCLC: 41% | 50 Gy (4 fxs)a | 2 local failures | PFS: 24% (2 years) |

| Oshiro et al.39 | 21 | recurrent or metastatic NSCLC: 95% | 25-39 Gy (1-10 fxs) | 60% (2 years) | OS: 62.2% (2 years) |

| Unger et al.40 | 20 | metastatic NSCLC: 85%; hilar/main bronchial lesions | 30-40 Gy (5 fxs) | 63% (1 year) | OS: 54% (1 year) |

| Milano et al.41 | 53 | NSCLC: 66%; metastatic NSCLC: 37% | 20-55 Gy (1-18 fxs) | 73% (2 years) | OS: 44% (2 years); T1-2: 72% |

| Chang et al.42 | 27 | T1-2 NSCLC: 48%; recurrent NSCLC: 52% | 40-50 Gy (5 fxs) | 3 failures (40 Gy) | - |

NSCLC: non-small cell lung carcinoma; fxs: fractions; DFS: disease-free survival; OS: overall survival; CSS: cancer-specific survival; and PFS: progression-free survival. aIn 57% of cases.

In the Netherlands, Haasbeek et al. reported data regarding the use of SBRT delivered in 8 fractions of 7.5 Gy to 63 patients with central lung lesions (hilar lesions, in 37, and lesions abutting the pericardium or mediastinal structures, in 26), comparing those patients with those receiving SBRT for the treatment of peripheral lesions. Median follow-up was 35 months, during which no grade 4/5 toxicity was observed, and late grade 3 toxicity was observed in only 4 patients, 2 of whom had chest pain and 2 of whom had worsening dyspnea. Three-year overall survival and local control rates were better in the group of patients with central lesions than in that of those with peripheral lesions: 64.3% vs. 51.1% (p = 0.09) and 92.6% vs. 90.2% (p = 0.9), respectively.36

Because toxicity is always a concern in patients with central lesions, one group of researchers conducted a systematic review of 20 studies and 563 central lung lesions treated with SBRT. Grade 3/4 toxicity was reported in 8.6% of cases, and SBRT-related mortality was 2.7%; albeit low, those rates were higher than those observed in the treatment of peripheral lesions. Three-year local control and overall survival rates were 60-100% and 50-75%, respectively.43

Table 3 (36-42) summarizes the data regarding SBRT toxicity in patients with central legions, and Table 4 (43-49) presents the treatment regimens used in studies showing no grade 3/4 toxicity.36

Table 3. Toxicity of stereotactic body radiation therapy for central lesions, in absolute numbers of patients.

| Study | Deaths | Grade 3 toxicitya | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acute | Late | ||

| Haasbeek et al.36 | cardiac death: 1; respiratory failure: 1 | 1 | 4 |

| Nuyttens et al.37 | - | 4 | 6 |

| Rowe et al.38 | bronchial necrosis: 1 | 4 | |

| Oshiro et al.39 | hemoptysis: 1 | 0 | 2 |

| Unger et al.40 | bronchial fistula: 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Milano et al.41 | bronchial/tracheal lesion: 4 | 0 | 1 |

| Chang et al.42 | - | 1 | |

Chest wall pain, dyspnea, rib fracture, pneumonitis, or chronic cough.

Table 4. Stereotactic body radiation therapy regimens used in the treatment of central lesions in studies showing no grade 3 or 4 toxicity.

| Study | Number of lesions/Number of patients | Dose |

|---|---|---|

| Xia et al.44 | 9/43 | 50 Gy/10 fxs |

| Guckenberger et al.45 | 22/159 | 48 Gy/8 fxs 26.0-37.5 Gy/1-3 fxs |

| Baba et al.43 | 29/124 | 44-52 Gy/4 fxs |

| Olsen et al.46 | 19/130 | 45-50 Gy/5 fxs 54 Gy/3 fxs |

| Takeda et al.47 | 33/232 | 50 Gy/5 fxs |

| Stephans et al.48 | 7/94 | 50 Gy/5 fxs 60 Gy/3 fxs |

| Janssen et al.49 | 29/65 | 40-48 Gy/8 fxs 37.5 Gy/3 fxs |

| fxs: fractions. |

For patients with early-stage NSCLC, SBRT appears to be safe and effective, being the best treatment option for inoperable patients with peripheral or central lesions.

SBRT in patients with clinical stage I NSCLC and no histological confirmation of cancer

It is common practice that patients with solitary pulmonary nodules are referred for therapeutic thoracotomy without previous histological confirmation. In a prospective study evaluating the impact of adding positron emission tomography (PET) to conventional staging, thoracotomy was found to have been "futile" (i.e., was performed in patients with benign disease) in less than 10% of cases.50

The probability of malignancy of a solitary pulmonary nodule can be estimated by age, nodule diameter, smoking history, presence of spiculated margins, affected lobe, and standardized uptake value as assessed by PET.51 According to the American College of Chest Physicians, for patients in whom the probability of malignancy is greater than 60%, surgery is recommended without a histological diagnosis.52

Although technical difficulties and biopsy-related complications are few, they can be decisive in a population of patients who are not surgical candidates and are referred for SBRT.

One of the most controversial topics in SBRT for the treatment of stage I NSCLC is the fact that some studies conducted in Europe have included a considerable proportion of patients without histological confirmation. In a large study conducted in the Netherlands (n = 676), in which all patients were staged by PET, 65% had no histological diagnosis.24 In a comparison between two cohorts of stage I NSCLC patients (with and without histological confirmation), no differences were found between the two regarding local control or survival, suggesting that the inclusion of benign lesions did not bias the results.53

In recent years, a rapid increase in the use of SBRT in stage I NSCLC patients in the USA has been accompanied by an increasing number of patients receiving SBRT solely on the basis of a clinical diagnosis; although such patients currently account for less than 10% of cases, a trend toward increased SBRT use without biopsy has been observed, indicating the possibility of a paradigm change in the near future.54

One group of authors proposed a model to inform decisions regarding SBRT in patients with solitary pulmonary nodules and comorbidities that increase biopsy risks, recommending the use of SBRT without pathological confirmation when the probability of cancer is higher than 85%.55

SBRT in patients with multiple tumors, second primary tumors, or previous treatment

The use of SBRT in patients who have multiple tumors, who have second primary tumors, or who have previously been treated is a concern because it can increase the risk of complications, especially those resulting from multiple overlapping doses or a reduced pulmonary reserve in patients operated on.

To date, all studies investigating patients with multiple tumors, second primary tumors, or previous treatment have been retrospective in nature, and none have clearly separated them. However, patients with multiple primary lung tumors, those with synchronous or metachronous second primary tumors, and those with local recurrence after conventional radiation therapy or surgery can be cured, as shown in previous studies.(56-58)

Two studies have investigated such patients. (59,60) One of the studies evaluated 101 patients with multiple synchronous or metachronous primary lung tumors initially treated with surgery, SBRT, or conventional radiation therapy and subsequently treated with SBRT for the second tumor. The study showed promising results regarding local control, survival, and toxicity. The incidence of pneumonitis was six times higher in the patients who had previously received conventional radiation therapy than in those who had not. Overall survival was better in the patients who had metachronous tumors than in those who had synchronous tumors.59 The other study showed significant toxicity in 36 patients who received SBRT for the treatment of intrathoracic recurrence after having previously received thoracic radiation therapy for localized or advanced disease (mean dose of 61 Gy); 30% of the patients experienced grade 3 toxicity.60

One group of authors reported outcomes of SBRT in 15 patients who had second primary tumors (stage I tumors) and who had undergone pneumonectomy for the primary tumor, half of whom had severe COPD. Only 2 patients developed grade 3 toxicity, and 1-year survival was 90%, showing that SBRT is a safe treatment option.61

In view of the aforementioned findings, SBRT emerges as a promising therapeutic tool in patients with multiple synchronous or metachronous lung lesions and no evidence of regional or distant spread. However, SBRT should be used with caution in patients who have previously received external beam radiation therapy with conventional fractionation and radical doses.

SBRT in operable patients

Patients with stage I lung cancer are candidates for curative treatment and can be divided into three major groups: 1) the group of low-risk surgical patients, who are usually treated by lobectomy; 2) the group of high-risk surgical patients, who are treated with sublobar (segmental or wedge) resection or SBRT; and 3) the group of medically inoperable patients, who are treated with external beam radiation therapy or SBRT.

To date, no randomized studies have compared surgical treatment with SBRT in operable (group 1 or group 2) patients; therefore, the only available data are from prospective studies or case series.

With regard to cases of borderline operability undergoing a more conservative surgical procedure (group 2 patients), an analysis of 19 studies reporting outcomes of SBRT or sublobar resection was published in 2013.62 High (90%) local control rates can be achieved with SBRT, being similar to those achieved with lobectomy, which in turn are higher than those achieved with sublobar resection. In comparison with sublobar resection, SBRT results in lower local recurrence rates (20% vs. 4%; p = 0.07) and lower toxicity.

With regard to low-risk surgical patients (group 1 patients), the available data are from comparisons across studies and from studies of low-risk surgical patients who refused surgery and underwent SBRT. To date, there have been at least three studies on this topic, a total of 264 patients having been studied (median age, 76 years). Local control rates were 93% and 73% for T1 and T2 tumors, respectively. The 3-year survival rate was similar to that achieved with surgical treatment, and the 5-year survival rates for T1 and T2 tumors were 72% and 62%, respectively. Regional and distant recurrence was 20%.(14,63,64)

In a meta-analysis of studies published between 2000 and 2012, the results obtained with SBRT were compared with those obtained with surgery in operable patients with stage I NSCLC. Forty SBRT studies-30 of which were retrospective-comprising a total of 4,850 patients and 23 surgery studies-all of which were retrospective-comprising a total of 7,051 patients were selected for inclusion. The median age was 74 years among the patients who received SBRT and 66 years among those who received surgical treatment. The median follow-up duration was 28 months for SBRT patients and 37 months for surgery patients. The overall survival rates at 1, 3, and 5 years were lower with SBRT (83.4%, 56.6%, and 41.2%, respectively) than with lobectomy (92.5%, 77.9%, and 66.1%, respectively) and limited lung resections (93.2%, 80.7%, and 71.7%, respectively). After adjustment for proportion of operable patients and age, SBRT and surgery had similar overall and disease-free survival. It is therefore clear that patients are selected to undergo SBRT or surgery, older patients undergoing the former and younger, clinically fit patients undergoing the latter.65

In view of the excellent results obtained with SBRT for early-stage lung cancer, the idea of substituting this noninvasive technique for surgery, which is the standard treatment, led to randomized studies comparing SBRT with surgery.(66-68) Despite the efforts of the investigators, all of the aforementioned studies were terminated early because of poor recruitment. It is unknown whether this was due to a lack of referral of patients to the studies or to patient unwillingness to participate in the randomization process.

The investigators of two of the aforementioned studies(66,67) performed a pooled analysis of the collected data.69 Eligible patients were those with clinical T1-2a (< 4 cm), N0M0, operable NSCLC. A total of 58 patients were enrolled and randomly assigned to SBRT (n = 31) or surgery (n = 27). The median follow-up duration was 40.2 months for the SBRT group and 35.4 months for the surgery group. Only 1 patient in the SBRT group died, compared with 6 in the surgery group. Estimated overall survival at 3 years was 95% in the SBRT group and 79% in the surgery group (hazard ratio = 0.14; 95% CI: 0.017-1.190; p = 0.037). Recurrence-free survival at 3 years was 86% in the SBRT group and 80% in the surgery group (hazard ratio = 0.69; 95% CI: 0.21-2.29; p = 0.54). Grade 3 treatment-related adverse events were observed in 3 (10%) of the patients in the SBRT group, no grade 4 events having been observed in that group. In the surgery group, 1 (4%) of the patients died of surgical complications and 12 (44%) had grade 3/4 treatment-related adverse events. The authors concluded that SBRT is at least equivalent to surgery in terms of survival and local control and has reduced toxicity. However, they stated that studies involving larger samples should be conducted in order to corroborate those results.

SBRT in patients with poor lung function or severe COPD

Most of the lung cancer patients who are candidates for SBRT are not surgical patients; therefore, it is important to evaluate the pulmonary toxicity of SBRT in this group of patients.

Several studies have evaluated lung function changes in patients undergoing SBRT. Although FEV1 and DLCO are generally reduced and can decrease further over time,(65,69,70) this has no impact on patient quality of life or survival.(70-76) In one of the aforementioned studies,72 a low body mass index, a high lung volume receiving 20 Gy of SBRT, and a high pre-treatment FVC were predictors of a decline in FVC of more than 10%. In the remaining studies, no clinical or technical risk factors for pulmonary toxicity were identified.

The results of pulmonary function testing in 55 patients included in the RTOG 0236 protocol73 and receiving SBRT for peripheral tumors showed a 5.8% decrease in FEV1 and a 6.3% decrease in DLCO after 2 years of follow-up. There were no major changes in oxygen saturation or arterial blood gases. Neither pre-treatment pulmonary function test results nor dosimetric parameters were predictive of late pulmonary effects, findings that were consistent with those of the remaining studies. Survival was higher among patients who were not surgical candidates because of poor lung function than among those who had good baseline lung function but were not surgical candidates because of cardiac comorbidities. This finding is consistent with those reported by Stephans et al.,74 who performed a functional assessment of 92 medically inoperable patients undergoing SBRT. Although reduced FEV1 and DLCO can be less than significant in patients with severe COPD, they can be significant in patients with normal lung function or mild to moderate COPD.72 In a study evaluating lung function in 30 patients undergoing SBRT, SBRT was found to reduce lung volume and improve DLCO in those without COPD (n = 23) when compared with those with COPD (n = 7).73

Patients with severe COPD (FEV1/FVC < 70% and FEV1 ≤ 50%) undergoing SBRT or surgery were evaluated in a review of the literature.76 Despite the negative selection of SBRT patients, the outcomes were comparable between the two treatment modalities: local or locoregional control rates ≥ 89% and 1- and 3-year survival rates of 79-95% and 43-70%, respectively, for SBRT and of 45-86% and 31-66%, respectively, for surgery. In addition to the fact that SBRT does not require hospitalization, mean 30-day mortality was 0% in the group of patients undergoing SBRT and 10% in that of those undergoing surgery.

There is consensus that poor lung function per se is not a contraindication to SBRT. In fact, SBRT is specifically indicated for such patients. However, individual characteristics such as tumor size, tumor location, comorbidities, and patient performance status should be taken into account when prescribing SBRT.

Ongoing studies

RTOG-081377: a multicenter phase II study evaluating dose escalation in patients with centrally located tumors of less than 5 cm (T1-2N0M0) in order to determine the maximum dose and toxicity profile of SBRT delivered in 5 fractions. Other outcome measures include local control rates, overall survival, and progression-free survival. Although patient recruitment has been completed, no results have yet been published.

RTOG-091578: a phase II study of medically inoperable patients with stage I NSCLC. Patients are randomized to receive 34 Gy in 1 fraction or 48 Gy in 4 fractions.

Final considerations

SBRT is an effective treatment option for early-stage (T1/T2N0) NSCLC of < 5 cm.

Patients who are not surgical candidates constitute the principal study population. However, SBRT is a treatment option for patients who are unwilling to undergo surgery.

Patients with peripheral tumors and those with central tumors can be treated with SBRT, although with different dose fractionation schedules.

Patients with multiple lesions or previous radiation therapy should be evaluated to receive SBRT.

Limited lung function and advanced age are not contraindications to SBRT.

In special situations, treatment can be initiated without a histopathological diagnosis of neoplasm, on the basis of clinical criteria, when a biopsy cannot be performed.

The risk of toxicity should be individually balanced against tumor location and patient prognosis.

The early termination of randomized studies comparing SBRT with surgery in operable patients demonstrates the difficulty in conducting phase III studies on this topic. However, evidence from a pooled analysis of two such studies shows that, in operable patients, SBRT is at least equivalent to surgery in terms of local control and survival, and has reduced toxicity.

A multidisciplinary evaluation plays a central role in therapeutic decision making, treatment, and follow-up.

Footnotes

Financial support: None.

Study carried out in the Departamento de Radioterapia, Hospital Sírio-Libanês, São Paulo (SP), in the Departamento de Radioterapia, Hospital Sírio-Libanês, Brasília (DF), and at the Departamento de Radioterapia, Instituto de Radiologia, Hospital das Clínicas, Faculdade de Medicina, Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo (SP) Brasil.

References

- 1.Jemal A, Bray F, Center MM, Ferlay J, Ward E, Forman D. Global cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin. 2011;61(2):69–90. doi: 10.3322/caac.20107. http://dx.doi.org/10.3322/caac.20107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Siegel R, Naishadham D, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin. 2012;62(1):10–29. doi: 10.3322/caac.20138. http://dx.doi.org/10.3322/caac.20138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Raz DJ, Zell JA, Ou SH, Gandara DR, Anton-Culver H, Jablons DM. Natural history of stage I non-small cell lung cancer implications for early detection. Chest. 2007;132(1):193–199. doi: 10.1378/chest.06-3096. http://dx.doi.org/10.1378/chest.06-3096 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rowell NP, Williams CJ. Radical radiotherapy for stage I/II non-small cell lung cancer in patients not sufficiently fit for or declining surgery (medically inoperable) Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2001;(2):CD002935–CD002935. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002935. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/14651858.cd002935 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nesbitt JC, Putnam JB, Walsh GL, Roth JA, Mountain CF. Survival in early-stage non-small cell lung cancer. Ann Thorac Surg. 1995;60(2):466–472. doi: 10.1016/0003-4975(95)00169-l. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0003-4975(95)00169-L [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Martel MK, Ten Haken RK, Hazuka MB, Kessler ML, Strawderman M, Turrisi AT. Estimation of tumor control probability model parameters from 3-D dose distributions of non-small cell lung cancer patients. Lung Cancer. 1999;24(1):31–37. doi: 10.1016/s0169-5002(99)00019-7. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0169-5002(99)00019-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Saunders M, Dische S, Barrett A, Harvey A, Griffiths G, Palmar M. Continuous, hyperfractionated, accelerated radiotherapy (CHART) versus conventional radiotherapy in non-small cell lung cancer mature data from the randomised multicentre trial. CHART Steering committee. Radiother Oncol. 1999;52(2):137–148. doi: 10.1016/s0167-8140(99)00087-0. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0167-8140(99)00087-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rosenman JG, Halle JS, Socinski MA, Deschesne K, Moore DT, Johnson H. High-dose conformal radiotherapy for treatment of stage IIIA/IIIB non-small-cell lung cancer technical issues and results of a phase I/II trial. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2002;54(2):348–356. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(02)02958-9. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0360-3016(02)02958-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Narayan S, Bradley JD. A randomized phase III comparison of standard-dose (60 Gy) versus high-dose (74 Gy) conformal chemoradiotherapy +/- cetuximab for stage IIIa/IIIb non-small cell lung cancer:Preliminary findings on radiation dose in RTOG 0617. Proceedings of the 53rd Annual Meeting of the American Society of Radiation Oncology; 2011 Oct 2-6; Miami, FL. Washington, DC: American Society for Radiation Oncology; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Blomgren H, Lax I, Näslund I, Svanström R. Stereotactic high dose fraction radiation therapy of extracranial tumors using an accelerator Clinical experience of the first thirty-one patients. Acta Oncol. 1995;34(6):861–870. doi: 10.3109/02841869509127197. http://dx.doi.org/10.3109/02841869509127197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.National Comprehensive Cancer Network . Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer NCCN Guidelines. Fort Washington, PA: NCCN; 2015. www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/nscl.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zeng J, Baik C, Bhatia S, Mayr N, Rengan R. Combination of stereotactic ablative body radiation with targeted therapies. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15(10):e426–e434. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(14)70026-9. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(14)70026-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chi A, Liao Z, Nguyen NP, Xu J, Stea B, Komaki R. Systemic review of the patterns of failure following stereotactic body radiation therapy in early-stage non-small-cell lung cancer clinical implications. Radiother Oncol. 2010;94(1):1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2009.12.008. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.radonc.2009.12.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Onishi H, Shirato H, Nagata Y, Hiraoka M, Fujino M, Gomi K. Stereotactic body radiotherapy (SBRT) for operable stage I non-small-cell lung cancer can SBRT be comparable to surgery? Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2011;81(5):1352–1358. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2009.07.1751. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrobp.2009.07.1751 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Timmerman R, Abdulrahman R, Kavanagh BD, Meyer JL. Meyer JL, Kavanagh BD, Purdy JA, Timmerman R. IMRT, IGRT, SBRT - Advances in the Treatment Planning and Delivery of Radiotherapy. Basel: Karger; 2007. Lung Cancer: A Model for Implementing SBRT into Practice; pp. 368–385.http://dx.doi.org/10.1159/000106047 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Radiation Therapy Oncology Group . RTOG 0236 Protocol Information, A phase II trial of stereotactic body radiation therapy (SBRT) in the treatment of patients with medically inoperable stage I/II non-small cell lung cancer. Philadelphia: RTOG; Feb, 2011. Sep, 2009. http://www.rtog.org/ClinicalTrials/ProtocolTable/StudyDetails.aspx?study=0236 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Radiation Therapy Oncology Group . 2015 Jun 22 - RTOG 0813 Protocol Information, Seamless phase I/II study of stereotactic lung radiotherapy (SBRT) for early stage, centrally located, non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) in medically inoperable patients. Philadelphia: RTOG; Jun, 2015. http://www.rtog.org/ClinicalTrials/ProtocolTable/StudyDetails.aspx?study=0813 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Timmerman R, McGarry R, Yiannoutsos C, Papiez L, Tudor K, DeLuca J. Excessive toxicity when treating central tumors in a phase II study of stereotactic body radiation therapy for medically inoperable early-stage lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(30):4833–4839. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.07.5937. http://dx.doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2006.07.5937 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fakiris AJ, McGarry RC, Yiannoutsos CT, Papiez L, Williams M, Henderson MA. Stereotactic body radiation therapy for early-stage non-small-cell lung carcinoma four-year results of a prospective phase II study. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2009;75(3):677–682. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2008.11.042. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrobp.2008.11.042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bral S, Gevaert T, Linthout N, Versmessen H, Collen C, Engels B. Prospective, risk-adapted strategy of stereotactic body radiotherapy for early-stage non-small-cell lung cancer results of a Phase II trial. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2011;80(5):1343–1349. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2010.04.056. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrobp.2010.04.056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Onishi H, Shirato H, Nagata Y, Hiraoka M, Fujino M, Gomi K. Hypofractionated stereotactic radiotherapy (HypoFXSRT) for stage I non-small cell lung cancer updated results of 257 patients in a Japanese multi-institutional study. J Thorac Oncol. 2007;2(7 Suppl 3):S94–100. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e318074de34. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/JTO.0b013e318074de34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nagata Y, Hiraoka M, Shibata T, Onishi H, Kokubo M, Karasawa K. Stereotactic Body Radiation Therapy For T1N0M0 Non-small Cell Lung Cancer First Report for Inoperable Population of a Phase II Trial by Japan Clinical Oncology Group (JCOG 0403) Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2012;84(Suppl):S46–S46. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2015.07.2278. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrobp.2012.07.330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Baumann P, Nyman J, Lax I, Friesland S, Hoyer M, Rehn Ericsson S. Factors important for efficacy of stereotactic body radiotherapy of medically inoperable stage I lung cancer A retrospective analysis of patients treated in the Nordic countries. Acta Oncol. 2006;45(7):787–795. doi: 10.1080/02841860600904862. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/02841860600904862 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Senthi S, Lagerwaard FJ, Haasbeek CJ, Slotman BJ, Senan S. Patterns of disease recurrence after stereotactic ablative radiotherapy for early stage non-small-cell lung cancer a retrospective analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13(8):802–809. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70242-5. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70242-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brown WT, Wu X, Fayad F, Fowler JF, Amendola BE, García S. CyberKnife radiosurgery for stage I lung cancer results at 36 months. Clin Lung Cancer. 2007;8(8):488–492. doi: 10.3816/CLC.2007.n.033. http://dx.doi.org/10.3816/CLC.2007.n.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Van der Voort van Zyp NC.Prévost J-B.Hoogeman MS.Praag J.van der Holt B.Levendag PC Stereotactic radiotherapy with real-time tumor tracking for non-small cell lung cancer clinical outcome. Radiother Oncol. 2009;91(3):296–300. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2009.02.011. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.radonc.2009.02.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Timmerman RD, Hu C, Michalski J, Straube W, Galvin J, Johnstone D. Long-term Results of RTOG 0236 A Phase II Trial of Stereotactic Body Radiation Therapy (SBRT) in the Treatment of Patients with Medically Inoperable Stage I Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2014;90(Suppl 1):S30–S30. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrobp.2014.05.135 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Timmerman RD, Paulus R, Pass HI, Gore E, Edelman MJ, Galvin JM. RTOG 0618 Stereotactic body radiation therapy (SBRT) to treat operable early-stage lung cancer patients. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(15 Suppl):7523–7523. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Palma D, Visser O, Lagerwaard FJ, Belderbos J, Slotman BJ, Senan S. Impact of introducing stereotactic lung radiotherapy for elderly patients with stage I non-small-cell lung cancer a population-based time-trend analysis. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(35):5153–5159. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.30.0731. http://dx.doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2010.30.0731 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Voroney JP, Hope A, Dahele MR, Purdie TG, Purdy T, Franks KN. Chest wall pain and rib fracture after stereotactic radiotherapy for peripheral non-small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2009;4(8):1035–1037. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3181ae2962. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/JTO.0b013e3181ae2962 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Forquer JA, Fakiris AJ, Timmerman RD, Lo SS, Perkins SM, McGarry RC. Brachial plexopathy from stereotactic body radiotherapy in early-stage NSCLC dose-limiting toxicity in apical tumor sites. Radiother Oncol. 2009;93(3):408–413. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2009.04.018. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.radonc.2009.04.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Andolino DL, Forquer JA, Henderson MA, Barriger RB, Shapiro RH, Brabham JG. Chest wall toxicity after stereotactic body radiotherapy for malignant lesions of the lung and liver. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2011;80(3):692–697. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2010.03.020. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrobp.2010.03.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McGarry RC, Papiez L, Williams M, Whitford T, Timmerman RD. Stereotactic body radiation therapy of early-stage non-small-cell lung carcinoma phase I study. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2005;63(4):1010–1015. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2005.03.073. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrobp.2005.03.073 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Timmerman R, Papiez L, McGarry R, Likes L, DesRosiers C, Frost S. Extracranial stereotactic radioablation results of a phase I study in medically inoperable stage I non-small cell lung cancer. Chest. 2003;124(5):1946–1955. doi: 10.1378/chest.124.5.1946. http://dx.doi.org/10.1378/chest.124.5.1946 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chi A, Nguyen NP, Komaki R. The potential role of respiratory motion management and image guidance in the reduction of severe toxicities following stereotactic ablative radiation therapy for patients with centrally located early stage non-small cell lung cancer or lung metastases. Front Oncol. 2014;4:151–151. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2014.00151. http://dx.doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2014.00151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Haasbeek CJ, Lagerwaard FJ, Slotman BJ, Senan S. Outcomes of stereotactic ablative radiotherapy for centrally located early-stage lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2011;6(12):2036–2043. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e31822e71d8. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/JTO.0b013e31822e71d8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nuyttens JJ. van der Voort van Zyp NC.Praag J.Aluwini S.van Klaveren RJ.Verhoef C Outcome of four-dimensional stereotactic radiotherapy for centrally located lung tumors. Radiother Oncol. 2012;102(3):383–387. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2011.12.023. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.radonc.2011.12.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rowe BP, Boffa DJ, Wilson LD, Kim AW, Detterbeck FC, Decker RH. Stereotactic body radiotherapy for central lung tumors. J Thorac Oncol. 2012;7(9):1394–1399. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3182614bf3. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/JTO.0b013e3182614bf3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Oshiro Y, Aruga T, Tsuboi K, Marino K, Hara R, Sanayama Y. Stereotactic body radiotherapy for lung tumors at the pulmonary hilum. Strahlenther Onkol. 2010;186(5):274–279. doi: 10.1007/s00066-010-2072-y. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00066-010-2072-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Unger K, Ju A, Oermann E, Suy S, Yu X, Vahdat S. CyberKnife for hilar lung tumors report of clinical response and toxicity. J Hematol Oncol. 2010;3:39–39. doi: 10.1186/1756-8722-3-39. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1756-8722-3-39 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Milano MT, Chen Y, Katz AW, Philip A, Schell MC, Okunieff P. Central thoracic lesions treated with hypofractionated stereotactic body radiotherapy. Radiother Oncol. 2009;91(3):301–306. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2009.03.005. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.radonc.2009.03.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chang JY, Balter PA, Dong L, Yang Q, Liao Z, Jeter M. Stereotactic body radiation therapy in centrally and superiorly located stage I or isolated recurrent non-small-cell lung cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2008;72(4):967–971. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2008.08.001. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrobp.2008.08.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Baba F, Shibamoto Y, Ogino H, Murata R, Sugie C, Iwata H. Clinical outcomes of stereotactic body radiotherapy for stage I non-small cell lung cancer using different doses depending on tumor size. Radiat Oncol. 2010;5:81–81. doi: 10.1186/1748-717X-5-81. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1748-717X-5-81 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Xia T, Li H, Sun Q, Wang Y, Fan N, Yu Y. Promising clinical outcome of stereotactic body radiation therapy for patients with inoperable Stage I/II non-small-cell lung cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2006;66(1):117–125. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2006.04.013. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrobp.2006.04.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Guckenberger M, Wulf J, Mueller G, Krieger T, Baier K, Gabor M. Dose-response relationship for image-guided stereotactic body radiotherapy of pulmonary tumors relevance of 4D dose calculation. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2009;74(1):47–54. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2008.06.1939. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrobp.2008.06.1939 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Olsen JR, Robinson CG, El Naqa I, Creach KM, Drzymala RE, Bloch C. Dose-response for stereotactic body radiotherapy in early-stage non-small-cell lung cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2011;81(4):e299–e303. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2011.01.038. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrobp.2011.01.038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Takeda A, Kunieda E, Ohashi T, Aoki Y, Koike N, Takeda T. Stereotactic body radiotherapy (SBRT) for oligometastatic lung tumors from colorectal cancer and other primary cancers in comparison with primary lung cancer. Radiother Oncol. 2011;101(2):255–259. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2011.05.033. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.radonc.2011.05.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Stephans KL, Djemil T, Reddy CA, Gajdos SM, Kolar M, Mason D. A comparison of two stereotactic body radiation fractionation schedules for medically inoperable stage I non-small cell lung cancer the Cleveland Clinic experience. J Thorac Oncol. 2009;4(8):976–982. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3181adf509. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/JTO.0b013e3181adf509 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Janssen S, Dickgreber NJ, Koenig C, Bremer M, Werner M, Karstens JH. Image-guided hypofractionated small volume radiotherapy of non-small cell lung cancer - feasibility and clinical outcome. Onkologie. 2012;35(7-8):408–412. doi: 10.1159/000340064. http://dx.doi.org/10.1159/000340064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.van Tinteren H, Hoekstra OS, Smit EF. van den Bergh JH.Schreurs AJ.Stallaert RA Effectiveness of positron emission tomography in the preoperative assessment of patients with suspected non-small-cell lung cancer the PLUS multicentre randomised trial. Lancet. 2002;359(9315):1388–1393. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(02)08352-6. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08352-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Herder GJ, van Tinteren H, Golding RP, Kostense PJ, Comans EF, Smit EF. Clinical prediction model to characterize pulmonary nodules validation and added value of 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography. Chest. 2005;128(4):2490–2496. doi: 10.1378/chest.128.4.2490. http://dx.doi.org/10.1378/chest.128.4.2490 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Scott WJ, Howington J, Feigenberg S, Movsas B, Pisters K. American College of Chest Physicians Treatment of non-small cell lung cancer stage I and stage II ACCP evidence-based clinical practice guidelines (2nd edition) Chest. 2007;132(3 Suppl):234S–242S. doi: 10.1378/chest.07-1378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Verstegen NE, Lagerwaard FJ, Haasbeek CJ, Slotman BJ, Senan S. Outcomes of stereotactic ablative radiotherapy following a clinical diagnosis of stage I NSCLC comparison with a contemporaneous cohort with pathologically proven disease. Radiother Oncol. 2011;101(2):250–254. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2011.09.017. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.radonc.2011.09.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rutter CE, Corso CD, Park HS, Mancini BR, Yeboa DN, Lester-Coll NH. Increase in the use of lung stereotactic body radiotherapy without a preceding biopsy in the United States. Lung Cancer. 2014;85(3):390–394. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2014.06.013. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.lungcan.2014.06.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Louie AV, Senan S, Patel P, Ferket BS, Lagerwaard FJ, Rodrigues GB. When is a biopsy-proven diagnosis necessary before stereotactic ablative radiotherapy for lung cancer : A decision analysis. Chest. 2014;146(4):1021–1028. doi: 10.1378/chest.13-2924. http://dx.doi.org/10.1378/chest.13-2924 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Aziz TM, Saad RA, Glasser J, Jilaihawi AN, Prakash D. The management of second primary lung cancers A single centre experience in 15 years. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2002;21(3):527–533. doi: 10.1016/s1010-7940(02)00024-6. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S1010-7940(02)00024-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kelsey CR, Clough RW, Marks LB. Local recurrence following initial resection of NSCLC salvage is possible with radiation therapy. Cancer J. 2006;12(4):283–288. doi: 10.1097/00130404-200607000-00006. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00130404-200607000-00006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bauman JE, Mulligan MS, Martins RG, Kurland BF, Eaton KD, Wood DE. Salvage lung resection after definitive radiation (>59 Gy) for non-small cell lung cancer surgical and oncologic outcomes. Ann Thorac Surg. 2008;86(5):1632–1638. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2008.07.042. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.athoracsur.2008.07.042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Chang JY, Liu YH, Zhu Z, Welsh JW, Gomez DR, Komaki R. Stereotactic ablative radiotherapy a potentially curable approach to early stage multiple primary lung cancer. Cancer. 2013;119(18):3402–3410. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28217. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/cncr.28217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kelly P, Balter PA, Rebueno N, Sharp HJ, Liao Z, Komaki R. Stereotactic body radiation therapy for patients with lung cancer previously treated with thoracic radiation. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2010;78(5):1387–1393. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2009.09.070. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrobp.2009.09.070 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Haasbeek CJ, Lagerwaard FJ, Antonisse ME, Slotman BJ, Senan S. Stage I nonsmall cell lung cancer in patients aged > or =75 years outcomes after stereotactic radiotherapy. Cancer. 2010;116(2):406–414. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24759. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/cncr.24759 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Mahmood S, Bilal H, Faivre-Finn C, Shah R. Is stereotactic ablative radiotherapy equivalent to sublobar resection in high-risk surgical patients with stage I non-small-cell lung cancer. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2013;17(5):845–853. doi: 10.1093/icvts/ivt262. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/icvts/ivt262 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Palma D, Visser O, Lagerwaard FJ, Belderbos J, Slotman B, Senan S. Treatment of stage I NSCLC in elderly patients a population-based matched-pair comparison of stereotactic radiotherapy versus surgery. Radiother Oncol. 2011;101(2):240–244. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2011.06.029. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.radonc.2011.06.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lagerwaard FJ, Verstegen NE, Haasbeek CJ, Slotman BJ, Paul MA, Smit EF. Outcomes of stereotactic ablative radiotherapy in patients with potentially operable stage I non-small cell lung cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2012;83(1):348–353. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2011.06.2003. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrobp.2011.06.2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zheng X, Schipper M, Kidwell K, Lin J, Reddy R, Ren Y. Survival outcome after stereotactic body radiation therapy and surgery for stage I non-small cell lung cancer a meta-analysis. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2014;90(3):603–611. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2014.05.055. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrobp.2014.05.055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.ClinicalTrials.gov . Trial of Either Surgery or Stereotactic Radiotherapy for Early Stage (IA) Lung Cancer (ROSEL) Bethesda (MD): National Library of Medicine (US); Jun, 2015. May, 2008. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00687986 [Google Scholar]

- 67.ClinicalTrials.gov . Identifier NCT00840749, Randomized Study to Compare CyberKnife to Surgical Resection In Stage I Non-small Cell Lung Cancer (STARS) Bethesda (MD): National Library of Medicine (US); Apr, 2013. Feb, 2009. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00840749 [Google Scholar]

- 68.Advanced Technology QA Center . ACOSOG PROTOCOL Z4099; RTOG PROTOCOL 1021, Randomized phase III study of sublobar resection (+/- brachytherapy) versus stereotactic body radiation therapy in high risk patients with stage I non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) St. Louis (MO): Washington University in St. Louis School of Medicine; May, 2011. http://atc.wustl.edu/protocols/rtog/1021/1021.html [Google Scholar]

- 69.Chang JY, Senan S, Paul MA, Mehran RJ, Louie AV, Balter P. Stereotactic ablative radiotherapy versus lobectomy for operable stage I non-small-cell lung cancer: a pooled analysis of two randomised trials. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16(6):630–637. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(15)70168-3. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(15)70168-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Guckenberger M, Kestin LL, Hope AJ, Belderbos J, Werner-Wasik M, Yan D. Is there a lower limit of pretreatment pulmonary function for safe and effective stereotactic body radiotherapy for early-stage non-small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2012;7(3):542–551. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e31824165d7. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/JTO.0b013e31824165d7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Stanic S, Paulus R, Timmerman RD, Michalski JM, Barriger RB, Bezjak A. No clinically significant changes in pulmonary function following stereotactic body radiation therapy for early- stage peripheral non-small cell lung cancer an analysis of RTOG 0236. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2014;88(5):1092–1099. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2013.12.050. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrobp.2013.12.050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Takeda A, Enomoto T, Sanuki N, Handa H, Aoki Y, Oku Y. Reassessment of declines in pulmonary function =1 year after stereotactic body radiotherapy. Chest. 2013;143(1):130–137. doi: 10.1378/chest.12-0207. http://dx.doi.org/10.1378/chest.12-0207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Bishawi M, Kim B, Moore WH, Bilfinger TV. Pulmonary function testing after stereotactic body radiotherapy to the lung. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2012;82(1):e107–e110. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2011.01.037. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrobp.2011.01.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Stephans KL, Djemil T, Reddy CA, Gajdos SM, Kolar M, Machuzak M. Comprehensive analysis of pulmonary function Test (PFT) changes after stereotactic body radiotherapy (SBRT) for stage I lung cancer in medically inoperable patients. J Thorac Oncol. 2009;4(7):838–844. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3181a99ff6. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/JTO.0b013e3181a99ff6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Henderson M, McGarry R, Yiannoutsos C, Fakiris A, Hoopes D, Williams M. Baseline pulmonary function as a predictor for survival and decline in pulmonary function over time in patients undergoing stereotactic body radiotherapy for the treatment of stage I non-small-cell lung cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2008;72(2):404–409. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2007.12.051. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrobp.2007.12.051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Palma D, Lagerwaard F, Rodrigues G, Haasbeek C, Senan S. Curative treatment of Stage I non-small-cell lung cancer in patients with severe COPD stereotactic radiotherapy outcomes and systematic review. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2012;82(3):1149–1156. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2011.03.005. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrobp.2011.03.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Radiation Therapy Oncology Group . 2015 Jun 8 - RTOG 0813 Protocol Information, Seamless Phase I/II Study of Stereotactic Lung Radiotherapy (SBRT) for Early Stage, Centrally Located, Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer (NSCLC) in Medically Inoperable Patients. Philadelphia: RTOG; Sep, 2013. https://www.rtog.org/ClinicalTrials/ProtocolTable/StudyDetails.aspx?study=0813 [Google Scholar]

- 78.Radiation Therapy Oncology Group . 2014 Mar 6 - RTOG 0915 Protocol Information, A Randomized Phase II Study Comparing 2 Stereotactic Body Radiation Therapy (SBRT) Schedules for Medically Inoperable Patients with Stage I Peripheral Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Philadelphia: RTOG; Mar, 2011. https://www.rtog.org/ClinicalTrials/ProtocolTable/StudyDetails.aspx?study=0915 [Google Scholar]