INTRODUCTION

The annual National Birth Defects Prevention Network (NBDPN) Congenital Malformations Surveillance Report includes state-level data on major birth defects (i.e., conditions present at birth that cause adverse structural changes in one or more parts of the body) and a directory of population-based birth defects surveillance systems in the United States. Beginning in 2012, these annually updated data and directory information are available in an electronic format accompanied by a data brief. This year’s report includes data from 41 population-based birth defects surveillance programs and a data brief highlighting the more common trisomy conditions (i.e., disorders characterized by an additional chromosome): trisomy 21 (commonly referred to as Down syndrome), trisomy 18, and trisomy 13.

State-Specific Data Collection and Presentation for Selected Birth Defects

Data collection

The NBDPN Data Committee, in collaboration with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), invited population-based birth defects surveillance programs in the United States to submit data on major birth defects affecting central nervous, eye, ear, cardiovascular, orofacial, gastrointestinal, genitourinary, and musculoskeletal systems, as well as trisomies, amniotic bands, and fetal alcohol syndrome. Table 1 lists these 47 conditions and their diagnostic codes (International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification [ICD-9-CM]; and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention/British Pediatric Association Classification of Diseases [CDC/BPA]).

Table 1.

ICD-9-CM and CDC/BPA Codes for 47 Birth Defects Reported in the NBDPN Annual Report

| Birth defects | ICD-9-CM codes | CDC/BPA codes |

|---|---|---|

| Central nervous system | ||

| Anencephalus | 740.0 – 740.1 | 740.00 – 740.10 |

| Spina bifida without anencephalus | 741.0 – 741.9 | 741.00 – 741.99 |

| w/o 740.0 – 740.10 | w/o 740.0 – 740.10 | |

| Hydrocephalus without spina bifida | 742.3 w/o 741.0, 741.9 | 742.30 – 742.39 |

| w/o 741.00 – 741.99 | ||

| Encephalocele | 742.0 | 742.00 – 742.09 |

| Microcephalus | 742.1 | 742.10 |

| Eye | ||

| Anophthalmia/microphthalmia | 743.0, 743.1 | 743.00 – 743.10 |

| Congenital cataract | 743.30 – 743.34 | 743.32 |

| Aniridia | 743.45 | 743.42 |

| Ear | ||

| Anotia/microtia | 744.01, 744.23 | 744.01, 744.21 |

| Cardiovascular | ||

| Common truncus | 745.0 | 745.00 |

| Transposition of great arteries | 745.10, .11, .12, .19 (For CCHD screening*, 745.10 only) |

745.10–745.19 (exclude 745.13, 745.15, 745.18) (For CCHD screening*, only 745.10, 745.11, 745.14, 745.19) |

| Tetralogy of Fallot | 745.2 | 745.20 – 745.21, 747.31 |

| Ventricular septal defect | 745.4 | 745.40 – 745.49 (exclude 745.487, 745.498) |

| Atrial septal defect | 745.5 | 745.51 – 745.59 |

| Atrioventricular septal defect (endocardial cushion defect) | 745.60, .61, .69 | 745.60 – 745.69, 745.487 |

| Pulmonary valve atresia and stenosis | 746.01, 746.02 | 746.00 – 746.01 |

| (For CCHD screening*, 746.01 only) | (For CCHD screening*, 746.00 only) | |

| Tricuspid valve atresia and stenosis | 746.1 | 746.10 (exclude 746.105) (For CCHD screening*, 746.10 exclude 746.105 and 746.106) |

| Ebstein anomaly | 746.2 | 746.20 |

| Aortic valve stenosis | 746.3 | 746.30 |

| Hypoplastic left heart syndrome | 746.7 | 746.70 |

| Patent ductus arteriosus | 747.0 | 747.00 |

| Coarctation of aorta | 747.10 | 747.10 – 747.19 |

| Total anomalous pulmonary | ||

| venous return (TAPVR) | 747.41 | 747.42 |

| Orofacial | ||

| Cleft palate without cleft lip | 749.0 | 749.00 – 749.09 |

| Cleft lip with and without cleft palate | 749.1, 749.2 | 749.10 – 749.29 |

| Choanal atresia | 748.0 | 748.0 |

| Gastrointestinal | ||

| Esophageal atresia/tracheoesophageal fistula | 750.3 | 750.30 – 750.35 |

| Rectal and large intestinal atresia/stenosis | 751.2 | 751.20 – 751.24 |

| Pyloric stenosis | 750.5 | 750.51 |

| Hirschsprung disease (congenital megacolon) | 751.3 | 751.30 – 751.34 |

| Biliary atresia | 751.61 | 751.65 |

| Genitourinary | ||

| Renal agenesis/hypoplasia | 753.0 | 753.00 – 753.01 |

| Bladder exstrophy | 753.5 | 753.50 |

| Obstructive genitourinary defect | 753.2, 753.6 | 753.20–29 and 753.60–69 |

| Hypospadias | 752.61 | 752.60 – 752.62 (exclude 752.61 and 752.621) |

| Epispadias | 752.62 | 752.61 |

| Musculoskeletal | ||

| Reduction deformity, upper limbs | 755.20 – 755.29 | 755.20 – 755.29 |

| Reduction deformity, lower limbs | 755.30 – 755.39 | 755.30 – 755.39 |

| Gastroschisis | 756.79 | 756.71 |

| Omphalocele | 756.79 | 756.70 |

| Congenital hip dislocation | 754.30, .31, .35 | 754.30 |

| Diaphragmatic hernia | 756.6 | 756.61 |

| Chromosomal | ||

| Trisomy 13 | 758.1 | 758.10 – 758.19 |

| Down syndrome (trisomy 21) | 758.0 | 758.00 – 758.09 |

| Trisomy 18 | 758.2 | 758.20 – 758.29 |

| Other | ||

| Fetus or newborn affected by maternal alcohol use | 760.71 | 760.71 |

| Amniotic bands | No code | 658.80 |

ICD-9-CM, International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification; CDC/BPA, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention/British Pediatric Association Classification of Diseases; NBDPN, National Birth Defects Protection Network; w/o, without; CCHD, critical congenital heart defect.

The primary targets for critical congenital heart defect (CCHD) screening include hypoplastic left heart syndrome, pulmonary atresia with intact septum, tetralogy of Fallot, total anomalous pulmonary venous return, dextro-Transposition of great arteries (d-TGA), tricuspid atresia, and truncus arteriosus.

Participating state birth defects programs provided counts of all cases of the birth defects listed in Table 1 as well as counts of live births and male live births in their catchment areas for births occurring from January 1, 2006 through December 31, 2010. The cases for all defects were reported by maternal census race/ethnic categories: White non-Hispanic, Black/African-American non-Hispanic, Hispanic, Asian/Pacific Islander non-Hispanic, American Indian/Alaska Native non-Hispanic. Additionally, trisomy cases were provided by six categories of maternal age at delivery: less than 20 years, 20 to 24 years, 25 to 29 years, 30 to 34 years, 35 to 39 years, and 40+ years.

Data presentation

State-specific data from 41 population-based birth defects surveillance programs in the United States are available on-line S1-S121. Similar to the previous NBDPN annual reports, the data for each program are presented by 5 maternal racial/ethnic categories for all reported defects and by 2 maternal age categories (less than 35 years, 35+ years) for Down syndrome, trisomy 18, and trisomy 13. Prevalence for each condition was calculated from the following formula to obtain the prevalence per 10,000 live births: (total birth defect cases for any pregnancy outcome for × years/total live births for × years) * 10,000 (Mason et al., 2005). The total live birth denominator is used for all reported birth defects except for hypospadias, which is calculated using a denominator of total male live births.

This data report attempts to present state surveillance data that was uniformly collected; however, differences in program methodology for case ascertainment can be expected, such as the use of different diagnostic coding systems to classify birth defects and varying administrative data sources. Some of these state-specific methods are included in the footnotes of the accompanying tables, but a more detailed description is provided in the state birth defects surveillance program directory, available on-line S122-S172.

Highlighting Trisomies

This year’s data brief focuses on the three most common aneuploidies (Down syndrome, trisomy 18, and trisomy 13). Trisomy occurs when there is an extra chromosome resulting in 47 chromosomes instead of 46. Most cases of trisomy involve an extra chromosome in all cells (full trisomy), but sometimes the extra chromosome is only contained in some cells (mosaic trisomy) or just a part of the extra chromosome is present in the affected cells (partial trisomy) (Sherman et al., 2007).

Down syndrome is the most common of these three aneuploidies, occurring in approximately 1 in 691 live births in the United States (Parker et al., 2010). This is followed by trisomy 18, affecting approximately 1 in 3762 live births and trisomy 13, affecting approximately 1 in 7906 live births (Parker et al., 2010).

Ascertainment of trisomy cases among the population-based birth defects surveillance systems includes a range of prenatal and postnatal data sources. These can include administrative databases, such as hospital discharge data, vital records, and Medicaid databases; in-patient and out-patient medical records; and specialty facilities, such as cytogenetic laboratories and prenatal diagnostic facilities. Approximately one-third of the birth defects programs use trained staff or abstractors who review medical records for case finding (active case-finding) while approximately two-thirds rely on hospital reporting and/or administrative databases (passive case-finding). Some of the programs with passive case-finding methodology engage in follow-up activities to confirm the reported cases. State-specific data sources and methodologies are included in the state birth defects surveillance program directory, available on-line S122-S172.

Trisomy Data Presentation

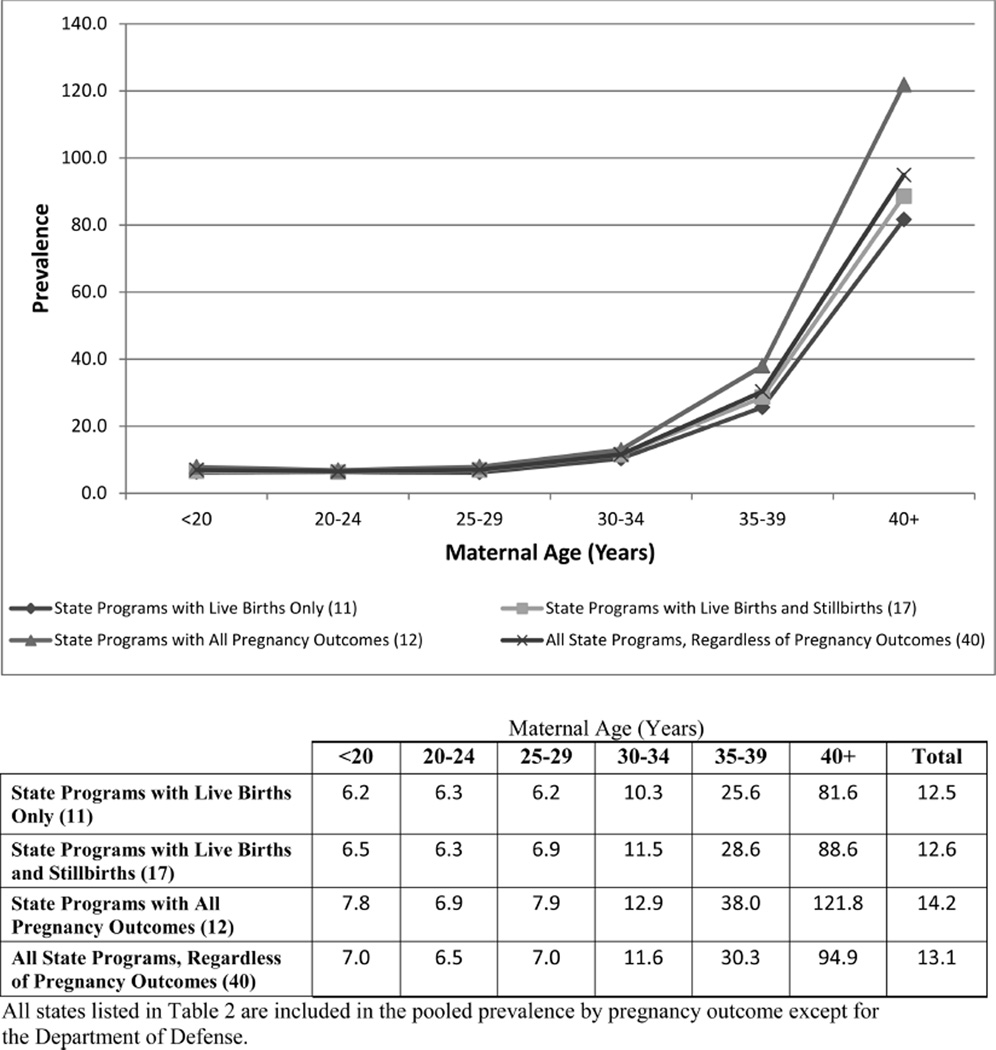

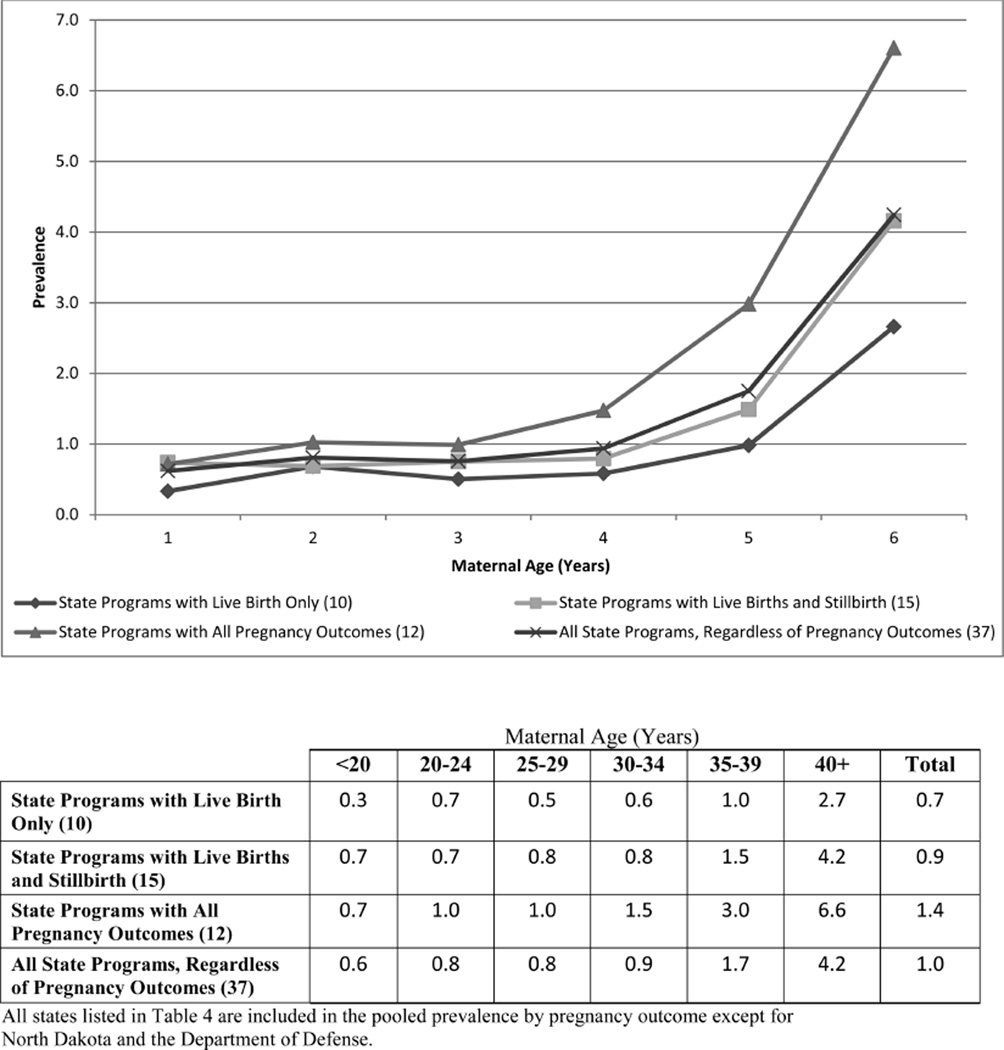

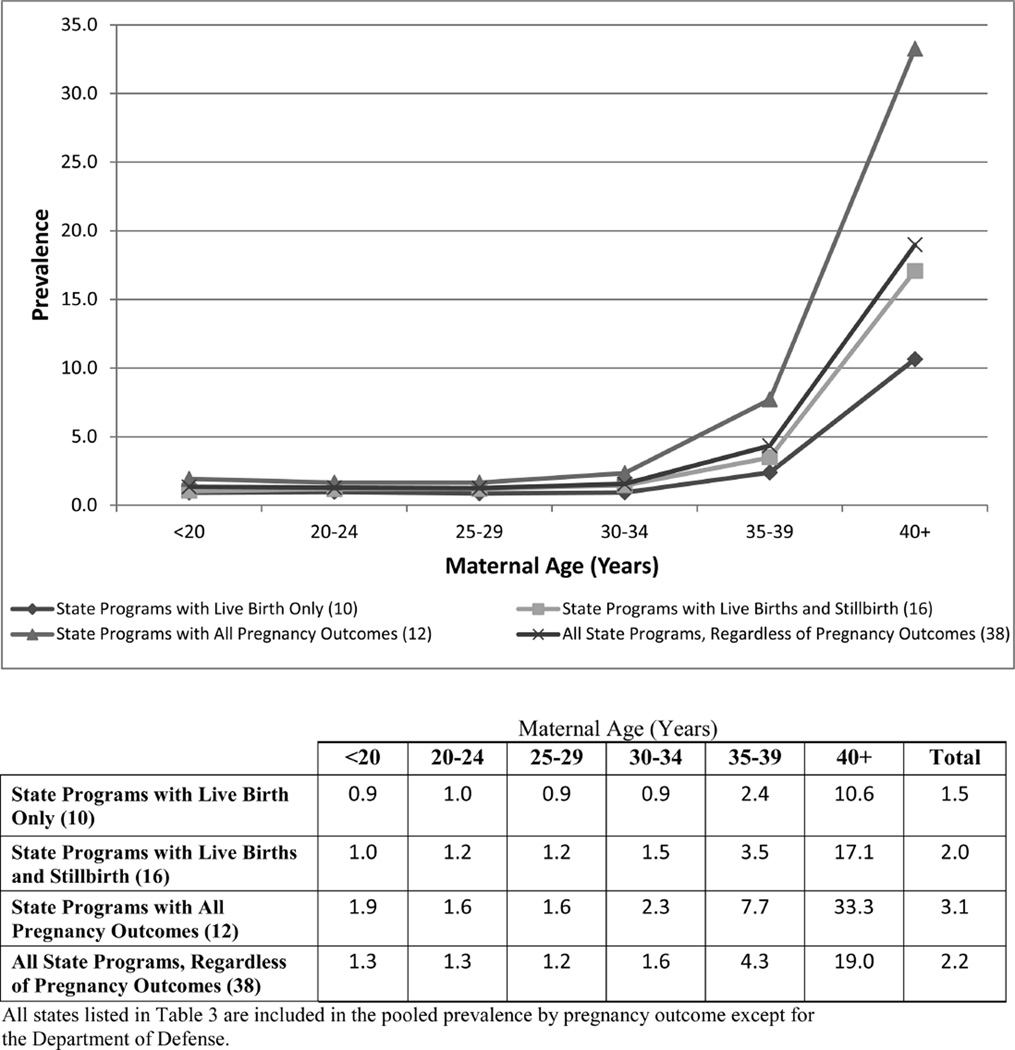

Table 2 presents the counts and live birth prevalence for Down syndrome by six maternal age categories (Table 2a) and by maternal race/ethnicity (Table 2b). The list of states is grouped by pregnancy outcomes reported: live births only, live births and stillbirths, or all pregnancy outcomes. The same stratifications are presented for trisomy 18 and 13 in Tables 3 and 4, respectively. A graphical presentation of the pooled prevalence of state programs by pregnancy outcomes and maternal age group for the trisomies is presented in Figures 1–3. The states that contributed to the pooled prevalence are listed in Tables 2 to 4.

Table 2.

| a Down Syndrome Counts and Prevalence by Maternal Age, 2006 to 2010 (Prevalence per 10,000 Live Births) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal age (years) | |||||||||

| State | <20 | 20–24 | 25–29 | 30–34 | 35–39 | 401 | Total* | Notes | |

| Live births | |||||||||

| Alaskap | 7 | 15 | 11 | 16 | 21 | 17 | 87 | 1 | |

| 12.9 | 9.2 | 6.7 | 14.6 | 39.1 | 121.3 | 15.6 | |||

| Department of Defensep | 20 | 165 | 156 | 167 | 160 | 112 | 804 | 6 | |

| 6.5 | 8.6 | 8.9 | 16.7 | 37.7 | 125.4 | 14.1 | |||

| Floridap | 84 | 222 | 207 | 269 | 400 | 301 | 1483 | ||

| 7.2 | 7.6 | 6.6 | 10.8 | 30.0 | 91.5 | 13.0 | |||

| Indianap | 32 | 59 | 88 | 119 | 119 | 98 | 515 | 10 | |

| 6.9 | 4.9 | 6.8 | 13.5 | 31.9 | 106.9 | 11.9 | |||

| Louisianaa | 11 | 23 | 30 | 35 | 42 | 37 | 178 | 12 | |

| 6.1 | 5.3 | 7.8 | 14.9 | 39.7 | 157.3 | 13.1 | |||

| Minnesotaa | 6 | 9 | 22 | 39 | 59 | 48 | 183 | 16 | |

| 4.8 | 4.8 | 6.5 | 11.8 | 34.3 | 110.5 | 15.3 | |||

| Nevadap | 13 | 24 | 35 | 42 | 62 | 46 | 258 | 23 | |

| 4.4 | 6.0 | 6.2 | 10.1 | 29.0 | 89.0 | 13.3 | |||

| New Jerseyp | 17 | 54 | 68 | 140 | 196 | 154 | 672 | 22 | |

| 5.0 | 5.7 | 4.8 | 8.5 | 20.7 | 66.0 | 12.2 | |||

| New Yorkp | 52 | 151 | 197 | 312 | 414 | 358 | 1484 | ||

| 6.2 | 6.1 | 6.1 | 9.7 | 21.9 | 70.6 | 12.2 | |||

| Vermontp | 2 | 3 | 7 | 6 | 12 | 9 | 39 | 30 | |

| 8.9 | 4.2 | 7.9 | 7.4 | 28.3 | 91.6 | 12.3 | |||

| Washingtonp | . | . | . | . | . | . | 461 | 31 | |

| . | . | . | . | . | . | 13.0 | |||

| West Virginiap | 2 | 11 | 8 | 11 | 8 | 6 | 70 | 32 | |

| 1.5 | 3.5 | 2.7 | 6.1 | 10.9 | 52.2 | 6.9 | |||

| Live births and stillbirths | |||||||||

| Arizonaa | 35 | 68 | 89 | 122 | 137 | 121 | 572 | 3 | |

| 6.1 | 5.4 | 6.6 | 12.1 | 28.0 | 91.3 | 11.8 | |||

| Delawarea | 0 | 6 | 4 | 13 | 9 | 10 | 43 | 5 | |

| 0.0 | 6.7 | 3.9 | 16.1 | 22.3 | 112.2 | 12.0 | |||

| Illinoisp | 61 | 118 | 155 | 217 | 310 | 249 | 1121 | 9 | |

| 7.2 | 6.2 | 6.4 | 9.9 | 28.1 | 99.7 | 12.9 | |||

| Kansasp | 8 | 32 | 38 | 34 | 40 | 36 | 203 | 11 | |

| 3.9 | 5.8 | 6.2 | 8.2 | 23.1 | 97.6 | 10.2 | |||

| Kentuckyp | 19 | 38 | 50 | 56 | 84 | 47 | 303 | ||

| 5.2 | 4.5 | 6.1 | 10.6 | 37.9 | 90.9 | 10.7 | |||

| Marylandp | 24 | 46 | 45 | 75 | 116 | 93 | 401 | 14 | |

| 7.5 | 5.8 | 4.4 | 7.6 | 20.8 | 64.8 | 10.5 | |||

| Massachusettsa | 16 | 42 | 55 | 105 | 146 | 122 | 486 | 13 | |

| 7.0 | 6.9 | 5.9 | 9.0 | 20.9 | 71.7 | 12.8 | |||

| Mainep | 4 | 14 | 18 | 13 | 23 | 9 | 81 | 15 | |

| 7.5 | 8.2 | 9.1 | 8.5 | 30.4 | 56.0 | 12.2 | |||

| Michiganp | 45 | 99 | 147 | 176 | 205 | 127 | 821 | ||

| 7.5 | 6.8 | 8.3 | 12.4 | 31.4 | 87.9 | 13.5 | |||

| Mississippip | 8 | 35 | 36 | 53 | 46 | 16 | 194 | ||

| 2.2 | 4.8 | 5.9 | 15.8 | 33.5 | 56.4 | 8.8 | |||

| Missourip | 34 | 72 | 89 | 108 | 137 | 68 | 508 | 17 | |

| 9.3 | 7.8 | 9.2 | 16.8 | 48.8 | 117.3 | 15.7 | |||

| North Dakotap | 2 | 4 | 7 | 12 | 8 | 7 | 41 | 19 | |

| 6.1 | 3.5 | 4.5 | 12.5 | 21.3 | 91.4 | 9.2 | |||

| Nebraskap | 5 | 25 | 46 | 53 | 50 | 48 | 227 | 20 | |

| 4.6 | 7.6 | 10.6 | 17.3 | 39.5 | 182.6 | 17.0 | |||

| Ohiop | 15 | 19 | 39 | 23 | 39 | 30 | 165 | ||

| 9.2 | 4.8 | 8.9 | 7.3 | 26.9 | 102.4 | 11.1 | |||

| Tennesseep | 46 | 97 | 109 | 97 | 144 | 93 | 586 | ||

| 8.6 | 7.8 | 9.2 | 12.2 | 40.4 | 128.2 | 14.0 | |||

| Virginiap | 27 | 83 | 76 | 139 | 147 | 125 | 732 | 29 | |

| 6.3 | 6.8 | 5.2 | 10.6 | 21.1 | 74.0 | 13.8 | |||

| Wisconsinp | 17 | 41 | 58 | 115 | 114 | 85 | 430 | ||

| 5.9 | 5.3 | 5.5 | 14.0 | 31.8 | 113.4 | 12.8 | |||

| All Pregnancy Outcomes | |||||||||

| Arkansasa | 17 | 39 | 46 | 45 | 52 | 39 | 238 | 2 | |

| 5.9 | 5.9 | 8.1 | 13.8 | 39.8 | 150.8 | 11.9 | |||

| Coloradop | 31 | 58 | 98 | 130 | 221 | 153 | 715 | 4 | |

| 9.7 | 7.4 | 10.2 | 15.3 | 49.1 | 150.4 | 20.6 | |||

| Georgia/CDCa | 26 | 50 | 71 | 110 | 163 | 96 | 535 | 7 | |

| 12.4 | 8.9 | 10.2 | 15.7 | 40.2 | 94.3 | 20.0 | |||

| Iowaa | 19 | 32 | 57 | 55 | 80 | 55 | 299 | 8 | |

| 11.0 | 6.4 | 8.6 | 12.4 | 44.9 | 150.6 | 15.0 | |||

| North Carolinaa | 55 | 106 | 118 | 152 | 205 | 132 | 771 | 18 | |

| 7.6 | 6.2 | 6.8 | 10.9 | 30.3 | 93.9 | 12.1 | |||

| New Hampshirea | 2 | 14 | 13 | 18 | 14 | 7 | 70 | 21 | |

| 4.8 | 10.1 | 6.7 | 9.4 | 14.4 | 32.4 | 10.2 | |||

| Oklahomaa | 21 | 59 | 60 | 48 | 76 | 67 | 332 | 24 | |

| 5.8 | 6.9 | 7.6 | 10.6 | 40.7 | 174.0 | 12.3 | |||

| Puerto Ricoa | 29 | 56 | 46 | 59 | 78 | 56 | 324 | 25 | |

| 7.1 | 7.7 | 7.8 | 16.2 | 50.1 | 161.6 | 14.2 | |||

| Rhode Islandp | 2 | 8 | 12 | 13 | 24 | 16 | 84 | 26 | |

| 3.8 | 6.5 | 7.9 | 8.9 | 29.5 | 86.0 | 14.6 | |||

| South Carolinaa | 16 | 25 | 33 | 26 | 54 | 35 | 189 | 27 | |

| 6.9 | 4.7 | 6.4 | 7.2 | 32.9 | 101.1 | 10.3 | |||

| Texasa | 173 | 302 | 338 | 436 | 570 | 390 | 2209 | 28 | |

| 7.9 | 6.8 | 7.7 | 13.4 | 36.7 | 119.3 | 13.7 | |||

| Utaha | 14 | 55 | 73 | 85 | 95 | 79 | 401 | ||

| 8.0 | 7.8 | 7.7 | 13.9 | 43.7 | 188.2 | 14.8 | |||

| b Down Syndrome Counts and Prevalence by Maternal Race/Ethnicity, 2006 to 2010 (Prevalence per 10,000 Live Births) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal race/ethnicity | ||||||||

| State | White non-Hispanic |

Black non-Hispanic |

Hispanic | Asian and Pacific Islanders Non-Hispanic |

American Indian/ Alaska Native Non-Hispanic |

Total* | Notes | |

| Live births | ||||||||

| Alaskap | 44 | . | . | . | 28 | 87 | 1 | |

| 13.0 | . | . | . | 20.0 | 15.6 | |||

| Department of Defensep | 550 | 105 | 90 | 35 | 9 | 804 | 6 | |

| 14.6 | 12.9 | 14.2 | 13.6 | 8.6 | 14.1 | |||

| Floridap | 667 | 314 | 423 | 45 | 4 | 1483 | ||

| 13.2 | 12.7 | 12.9 | 14.6 | 17.9 | 13.0 | |||

| Indianap | 403 | 37 | 53 | 15 | 1 | 515 | 10 | |

| 12.6 | 6.6 | 13.7 | 15.5 | 12.8 | 11.9 | |||

| Louisianaa | 106 | 54 | 9 | 8 | <5 | 178 | 12 | |

| 15.0 | 9.9 | 12.9 | 31.7 | . | 13.1 | |||

| Minnesotaa | 89 | 45 | 25 | 15 | 3 | 183 | 16 | |

| 14.1 | 20.3 | 17.9 | 9.9 | 19.9 | 15.3 | |||

| Nevadap | 84 | 24 | 125 | 17 | 1 | 258 | 23 | |

| 10.3 | 13.7 | 16.7 | 11.1 | 4.4 | 13.3 | |||

| New Jerseyp | 307 | 102 | 200 | 38 | 3 | 672 | 22 | |

| 12.0 | 12.3 | 14.0 | 7.0 | 48.1 | 12.2 | |||

| New Yorkp | 735 | 263 | 357 | 92 | 1 | 1484 | ||

| 12.4 | 13.3 | 12.9 | 7.3 | 4.3 | 12.2 | |||

| Vermontp | 36 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 39 | 30 | |

| 12.0 | 26.7 | 26.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 12.3 | |||

| Washingtonp | . | . | . | . | . | 461 | 31 | |

| . | . | . | . | . | 13.0 | |||

| West Virginiap | 48 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 70 | 32 | |

| 5.1 | 8.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 6.9 | |||

| Live births and stillbirths | ||||||||

| Arizonaa | 239 | 19 | 253 | 16 | 35 | 571 | 3 | |

| 11.7 | 9.8 | 12.2 | 10.2 | 11.5 | 11.8 | |||

| Delawarea | 28 | 7 | 4 | 4 | 0 | 43 | 5 | |

| 14.6 | 7.3 | 7.4 | 25.4 | 0.0 | 12.0 | |||

| Illinoisp | 753 | 149 | 165 | 39 | 1 | 1121 | 9 | |

| 16.4 | 9.8 | 7.9 | 8.4 | 8.1 | 12.9 | |||

| Kansasp | 130 | 6 | 36 | 5 | 0 | 203 | 11 | |

| 9.2 | 4.3 | 11.0 | 8.8 | 0.0 | 10.2 | |||

| Kentuckyp | 248 | 28 | 17 | 4 | 1 | 303 | ||

| 10.5 | 10.8 | 11.8 | 10.2 | 29.7 | 10.7 | |||

| Marylandp | 199 | 112 | 45 | 26 | 1 | 401 | 14 | |

| 11.3 | 8.8 | 8.8 | 10.0 | 12.3 | 10.5 | |||

| Massachusettsa | 315 | 53 | 75 | 28 | 3 | 486 | 13 | |

| 12.3 | 15.9 | 13.9 | 9.7 | 38.4 | 12.8 | |||

| Mainep | 71 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 81 | 15 | |

| 11.5 | 5.8 | 29.3 | 0.0 | 17.8 | 12.2 | |||

| Michiganp | 578 | 136 | 39 | 31 | 3 | 821 | ||

| 13.7 | 12.4 | 8.8 | 14.6 | 10.5 | 13.6 | |||

| Mississippip | 100 | 77 | 9 | 1 | 1 | 194 | ||

| 9.1 | 7.8 | 12.0 | 4.3 | 6.5 | 8.8 | |||

| Missourip | 395 | 48 | 40 | 18 | 4 | 508 | 17 | |

| 16.1 | 9.8 | 22.2 | 23.0 | 27.0 | 15.7 | |||

| North Dakotap | 35 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 41 | 19 | |

| 9.8 | 13.9 | 0.0 | 33.2 | 0.0 | 9.2 | |||

| Nebraskap | 163 | 10 | 42 | 5 | 1 | 227 | 20 | |

| 16.5 | 11.5 | 20.6 | 16.0 | 4.8 | 17.0 | |||

| Ohiop | 126 | 27 | 8 | 3 | 1 | 165 | ||

| 11.1 | 10.9 | 11.6 | 9.6 | 46.3 | 11.1 | |||

| Tennesseep | 393 | 116 | 64 | 10 | 0 | 586 | ||

| 14.0 | 13.3 | 16.5 | 12.2 | 0.0 | 14.0 | |||

| Virginiap | 322 | 114 | 113 | 43 | 0 | 732 | 29 | |

| 10.6 | 9.9 | 16.2 | 11.7 | 0.0 | 13.8 | |||

| Wisconsinp | 307 | 26 | 65 | 27 | 5 | 430 | ||

| 12.3 | 7.4 | 19.3 | 19.1 | 9.2 | 12.8 | |||

| All pregnancy outcomes | ||||||||

| Arkansasa | 176 | 26 | 33 | 3 | 0 | 238 | 2 | |

| 13.1 | 6.7 | 15.5 | 6.9 | 0.0 | 11.9 | |||

| Coloradop | 295 | 30 | 169 | 17 | 1 | 715 | 4 | |

| 14.3 | 19.4 | 15.7 | 14.6 | 4.0 | 20.6 | |||

| Georgia/CDCa | 173 | 165 | 127 | 25 | 2 | 535 | 7 | |

| 23.0 | 16.1 | 20.2 | 15.4 | 78.1 | 20.0 | |||

| Iowaa | 237 | 8 | 38 | 10 | 0 | 299 | 8 | |

| 14.1 | 9.6 | 23.3 | 20.6 | 0.0 | 15.0 | |||

| North Carolinaa | 434 | 143 | 143 | 26 | 14 | 771 | 18 | |

| 12.2 | 9.5 | 13.8 | 13.1 | 16.0 | 12.1 | |||

| New Hampshirea | 49 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 70 | 21 | |

| 7.9 | 8.8 | 12.8 | 12.4 | 64.5 | 10.2 | |||

| Oklahomaa | 203 | 24 | 67 | 6 | 32 | 332 | 24 | |

| 11.8 | 9.8 | 18.9 | 9.9 | 10.6 | 12.3 | |||

| Puerto Ricoa | 0 | 0 | 324 | 0 | 0 | 324 | 25 | |

| . | . | 14.2 | . | . | 14.2 | |||

| Rhode Islandp | 48 | 5 | 16 | 2 | 0 | 84 | 26 | |

| 13.4 | 10.1 | 13.4 | 7.9 | 0.0 | 14.6 | |||

| South Carolinaa | 109 | 52 | 21 | 4 | 0 | 189 | 27 | |

| 10.6 | 8.7 | 12.4 | 12.8 | 0.0 | 10.3 | |||

| Texasa | 703 | 182 | 1232 | 67 | 3 | 2209 | 28 | |

| 12.7 | 9.9 | 15.3 | 11.2 | 10.3 | 13.7 | |||

| Utaha | 285 | 5 | 84 | 14 | 3 | 401 | ||

| 13.7 | 19.4 | 19.3 | 15.5 | 8.8 | 14.8 | |||

Total includes unknown maternal age.

Active case-finding

Passive case-finding (with or without case confirmation).

Total includes unknown race.

active case-finding

passive-case finding (with or without case confirmation).

Table 3.

| a Trisomy 18 Counts and Prevalence by Maternal Age, 2006 to 2010 (Prevalence per 10,000 Live Births) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal Age (Years) | ||||||||

| State | <20 | 20–24 | 25–29 | 30–34 | 35–39 | 401 | Total* | Notes |

| Live births | ||||||||

| Alaskap | <6 | <6 | <6 | <6 | <6 | <6 | 10 | 1 |

| . | . | . | . | . | . | 1.8 | ||

| Department of Defensep | 5 | 14 | 27 | 14 | 18 | 16 | 99 | 6 |

| 1.6 | 0.7 | 1.5 | 1.4 | 4.2 | 17.9 | 1.7 | ||

| Floridap | 12 | 43 | 34 | 39 | 40 | 49 | 217 | |

| 1.0 | 1.5 | 1.1 | 1.6 | 3.0 | 14.9 | 1.9 | ||

| Indianap | 3 | 5 | 12 | 11 | 8 | 13 | 53 | 10 |

| 0.6 | 0.4 | 0.9 | 1.2 | 2.1 | 14.2 | 1.2 | ||

| Louisianaa | <5 | <5 | 7 | <5 | 5 | <5 | 24 | 12 |

| . | . | 1.8 | . | 4.7 | . | 1.8 | ||

| Minnesotaa | 3 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 6 | 8 | 24 | 16 |

| 2.4 | 0.5 | 0.9 | 0.9 | 3.5 | 18.4 | 2.0 | ||

| Nevadap | 4 | 3 | 5 | 4 | 2 | 9 | 32 | 23 |

| 1.4 | 0.7 | 0.9 | 1.0 | 0.9 | 17.4 | 1.7 | ||

| New Jerseyp | 1 | 9 | 6 | 11 | 17 | 13 | 57 | 22 |

| 0.3 | 1.0 | 0.4 | 0.7 | 1.8 | 5.6 | 1.0 | ||

| New Yorkp | 5 | 19 | 22 | 19 | 42 | 39 | 146 | |

| 0.6 | 0.8 | 0.7 | 0.6 | 2.2 | 7.7 | 1.2 | ||

| Vermontp | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 30 |

| 0.0 | 2.8 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 10.2 | 0.9 | ||

| West Virginiap | 1 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 11 | 32 |

| 0.8 | 0.3 | 1.0 | 0.6 | 0.0 | 26.1 | 1.1 | ||

| Live births and stillbirths | ||||||||

| Arizonaa | 3 | 15 | 23 | 17 | 12 | 18 | 89 | 3 |

| 0.5 | 1.2 | 1.7 | 1.7 | 2.4 | 13.6 | 1.8 | ||

| Delawarea | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 10 | 5 |

| 2.8 | 1.1 | 2.0 | 1.2 | 5.0 | 33.7 | 2.8 | ||

| Illinoisp | 7 | 23 | 27 | 27 | 51 | 38 | 192 | 9 |

| 0.8 | 1.2 | 1.1 | 1.2 | 4.6 | 15.2 | 2.2 | ||

| Kansasp | 0 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 7 | 26 | 11 |

| 0.0 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 1.2 | 2.9 | 19.0 | 1.3 | ||

| Kentuckyp | 1 | 5 | 3 | 4 | 14 | 6 | 45 | |

| 0.3 | 0.6 | 0.4 | 0.8 | 6.3 | 11.6 | 1.6 | ||

| Marylandp | 4 | 10 | 14 | 20 | 23 | 36 | 108 | 14 |

| 1.2 | 1.3 | 1.4 | 2.0 | 4.1 | 25.1 | 2.8 | ||

| Massachusettsa | 4 | 11 | 7 | 10 | 10 | 20 | 62 | 13 |

| 1.7 | 1.8 | 0.7 | 0.9 | 1.4 | 11.7 | 1.6 | ||

| Michiganp | 6 | 21 | 28 | 25 | 20 | 28 | 132 | |

| 1.0 | 1.4 | 1.6 | 1.8 | 3.1 | 19.4 | 2.2 | ||

| Mississippip | 1 | 7 | 7 | 8 | 7 | 2 | 32 | |

| 0.3 | 1.0 | 1.2 | 2.4 | 5.1 | 7.0 | 1.5 | ||

| Missourip | 5 | 17 | 14 | 13 | 18 | 16 | 83 | 17 |

| 1.4 | 1.9 | 1.4 | 2.0 | 6.4 | 27.6 | 2.6 | ||

| North Dakotap | 0 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 5 | 19 |

| 0.0 | 2.6 | 0.6 | 0.0 | 2.7 | 0.0 | 1.1 | ||

| Nebraskap | 2 | 7 | 11 | 7 | 8 | 8 | 43 | 20 |

| 1.8 | 2.1 | 2.5 | 2.3 | 6.3 | 30.4 | 3.2 | ||

| Ohiop | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 6 | 10 | 23 | |

| 1.2 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.3 | 4.1 | 34.1 | 1.5 | ||

| Tennesseep | 9 | 18 | 17 | 4 | 18 | 10 | 76 | |

| 1.7 | 1.5 | 1.4 | 0.5 | 5.0 | 13.8 | 1.8 | ||

| Virginiap | 4 | 7 | 7 | 21 | 19 | 17 | 89 | 29 |

| 0.9 | 0.6 | 0.5 | 1.6 | 2.7 | 10.1 | 1.7 | ||

| Wisconsinp | 6 | 6 | 15 | 13 | 10 | 16 | 66 | |

| 2.1 | 0.8 | 1.4 | 1.6 | 2.8 | 21.3 | 2.0 | ||

| All pregnancy outcomes | ||||||||

| Arkansasa | 6 | 6 | 9 | 9 | 11 | 14 | 55 | 2 |

| 2.1 | 0.9 | 1.6 | 2.8 | 8.4 | 54.1 | 2.7 | ||

| Coloradop | 6 | 17 | 19 | 31 | 44 | 39 | 164 | 4 |

| 1.9 | 2.2 | 2.0 | 3.7 | 9.8 | 38.3 | 4.7 | ||

| Georgia/CDCa | 2 | 13 | 11 | 14 | 36 | 53 | 131 | 7 |

| 1.0 | 2.3 | 1.6 | 2.0 | 8.9 | 52.1 | 4.9 | ||

| Iowaa | 7 | 4 | 13 | 16 | 17 | 12 | 69 | 8 |

| 4.1 | 0.8 | 2.0 | 3.6 | 9.5 | 32.9 | 3.5 | ||

| North Carolinaa | 16 | 36 | 22 | 26 | 43 | 36 | 181 | 18 |

| 2.2 | 2.1 | 1.3 | 1.9 | 6.4 | 25.6 | 2.8 | ||

| New Hampshirea | 0 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 5 | 11 | 21 |

| 0.0 | 0.7 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 23.1 | 1.6 | ||

| Oklahomaa | 6 | 13 | 10 | 10 | 9 | 8 | 56 | 24 |

| 1.7 | 1.5 | 1.3 | 2.2 | 4.8 | 20.8 | 2.1 | ||

| Puerto Ricoa | 13 | 11 | 16 | 10 | 22 | 11 | 83 | 25 |

| 3.2 | 1.5 | 2.7 | 2.7 | 14.1 | 31.7 | 3.6 | ||

| Rhode Islandp | 1 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 5 | 4 | 19 | 26 |

| 1.9 | 1.6 | 1.3 | 2.0 | 6.2 | 21.5 | 3.3 | ||

| South Carolinaa | 6 | 5 | 9 | 2 | 8 | 11 | 41 | 27 |

| 2.6 | 0.9 | 1.7 | 0.6 | 4.9 | 31.8 | 2.2 | ||

| Texasa | 32 | 73 | 66 | 70 | 113 | 94 | 448 | 28 |

| 1.5 | 1.6 | 1.5 | 2.2 | 7.3 | 28.8 | 2.8 | ||

| Utaha | 4 | 12 | 22 | 19 | 22 | 20 | 99 | |

| 2.3 | 1.7 | 2.3 | 3.1 | 10.1 | 47.6 | 3.7 | ||

| b Trisomy 18 Counts and Prevalence by Maternal Race/Ethnicity, 2006–2010 (Prevalence per 10,000 Live Births) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal race/ethnicity | ||||||||

| State | White non-Hispanic |

Black non-Hispanic |

Hispanic | Asian and Pacific Islanders |

American Indian/ Alaska Native |

Total* | Notes | |

| Live births | ||||||||

| Alaskap | <6 | . | . | . | <6 | 10 | 1 | |

| . | . | . | . | . | 1.8 | |||

| Department of Defensep | 70 | 9 | 14 | 5 | 0 | 99 | 6 | |

| 1.9 | 1.1 | 2.2 | 1.9 | 0.0 | 1.7 | |||

| Floridap | 80 | 67 | 59 | 6 | 0 | 217 | ||

| 1.6 | 2.7 | 1.8 | 1.9 | 0.0 | 1.9 | |||

| Indianap | 37 | 9 | 5 | 1 | 0 | 53 | 10 | |

| 1.2 | 1.6 | 1.3 | 1.0 | 0.0 | 1.2 | |||

| Louisianaa | 15 | 5 | <5 | <5 | 0 | 24 | 12 | |

| 2.1 | 0.9 | . | . | 0.0 | 1.8 | |||

| Minnesotaa | 11 | 8 | 1 | 4 | 0 | 24 | 16 | |

| 1.7 | 3.6 | 0.7 | 2.6 | 0.0 | 2.0 | |||

| Nevadap | 9 | 1 | 19 | 2 | 0 | 32 | 23 | |

| 1.1 | 0.6 | 2.5 | 1.3 | 0.0 | 1.7 | |||

| New Jerseyp | 20 | 15 | 17 | 5 | 0 | 57 | 22 | |

| 0.8 | 1.8 | 1.2 | 0.9 | 0.0 | 1.0 | |||

| New Yorkp | 54 | 38 | 41 | 10 | 0 | 146 | ||

| 0.9 | 1.9 | 1.5 | 0.8 | 0.0 | 1.2 | |||

| Vermontp | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 30 | |

| 1.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.9 | |||

| West Virginiap | 9 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 11 | 32 | |

| 1.0 | 2.7 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1.1 | |||

| Live births and stillbirths | ||||||||

| Arizonaa | 36 | 3 | 35 | 5 | 10 | 89 | 3 | |

| 1.8 | 1.5 | 1.7 | 3.2 | 3.3 | 1.8 | |||

| Delawarea | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 10 | 5 | |

| 2.1 | 3.1 | 3.7 | 6.4 | 0.0 | 2.8 | |||

| Illinoisp | 109 | 35 | 36 | 11 | 0 | 192 | 9 | |

| 2.4 | 2.3 | 1.7 | 2.4 | 0.0 | 2.2 | |||

| Kansasp | 14 | 1 | 9 | 0 | 0 | 26 | 11 | |

| 1.0 | 0.7 | 2.7 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1.3 | |||

| Kentuckyp | 40 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 45 | ||

| 1.7 | 0.4 | 2.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1.6 | |||

| Marylandp | 59 | 21 | 15 | 6 | 0 | 108 | 14 | |

| 3.4 | 1.6 | 2.9 | 2.3 | 0.0 | 2.8 | |||

| Massachusettsa | 29 | 11 | 15 | 4 | 0 | 62 | 13 | |

| 1.1 | 3.3 | 2.8 | 1.4 | 0.0 | 1.6 | |||

| Michiganp | 86 | 33 | 5 | 3 | 0 | 132 | ||

| 2.0 | 3.0 | 1.1 | 1.4 | 0.0 | 2.2 | |||

| Mississippip | 16 | 13 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 32 | ||

| 1.5 | 1.3 | 2.7 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1.5 | |||

| Missourip | 61 | 12 | 7 | 2 | 0 | 83 | 17 | |

| 2.5 | 2.4 | 3.9 | 2.6 | 0.0 | 2.6 | |||

| North Dakotap | 4 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 5 | 19 | |

| 1.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 16.6 | 0.0 | 1.1 | |||

| Nebraskap | 31 | 5 | 5 | 0 | 1 | 43 | 20 | |

| 3.1 | 5.7 | 2.5 | 0.0 | 4.8 | 3.2 | |||

| Ohiop | 15 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 23 | ||

| 1.3 | 3.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1.5 | |||

| Tennesseep | 51 | 14 | 10 | 1 | 0 | 76 | ||

| 1.8 | 1.6 | 2.6 | 1.2 | 0.0 | 1.8 | |||

| Virginiap | 43 | 17 | 7 | 7 | 0 | 89 | 29 | |

| 1.4 | 1.5 | 1.0 | 1.9 | 0.0 | 1.7 | |||

| Wisconsinp | 50 | 7 | 6 | 2 | 0 | 66 | ||

| 2.0 | 2.0 | 1.8 | 1.4 | 0.0 | 2.0 | |||

| All pregnancy outcomes | ||||||||

| Arkansasa | 38 | 11 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 55 | 2 | |

| 2.8 | 2.8 | 2.8 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 2.7 | |||

| Coloradop | 35 | 3 | 33 | 5 | 0 | 164 | 4 | |

| 1.7 | 1.9 | 3.1 | 4.3 | 0.0 | 4.7 | |||

| Georgia/CDCa | 47 | 33 | 17 | 10 | 1 | 131 | 7 | |

| 6.3 | 3.2 | 2.7 | 6.2 | 39.1 | 4.9 | |||

| Iowaa | 53 | 6 | 8 | 1 | 0 | 69 | 8 | |

| 3.2 | 7.2 | 4.9 | 2.1 | 0.0 | 3.5 | |||

| North Carolinaa | 99 | 38 | 25 | 10 | 2 | 181 | 18 | |

| 2.8 | 2.5 | 2.4 | 5.0 | 2.3 | 2.8 | |||

| New Hampshirea | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 11 | 21 | |

| 1.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1.6 | |||

| Oklahomaa | 37 | 9 | 2 | 1 | 7 | 56 | 24 | |

| 2.1 | 3.7 | 0.6 | 1.6 | 2.3 | 2.1 | |||

| Puerto Ricoa | 0 | 0 | 83 | 0 | 0 | 83 | 25 | |

| . | . | 3.6 | . | . | 3.6 | |||

| Rhode Islandp | 11 | 1 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 19 | 26 | |

| 3.1 | 2.0 | 3.4 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 3.3 | |||

| South Carolinaa | 22 | 13 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 41 | 27 | |

| 2.1 | 2.2 | 3.5 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 2.2 | |||

| Texasa | 147 | 49 | 223 | 22 | 0 | 448 | 28 | |

| 2.7 | 2.7 | 2.8 | 3.7 | 0.0 | 2.8 | |||

| Utaha | 75 | 5 | 15 | 1 | 1 | 99 | ||

| 3.6 | 19.4 | 3.4 | 1.1 | 2.9 | 3.7 | |||

Total includes unknown maternal age.

active case-finding

passive case-finding (with or without case confirmation).

Total includes unknown race.

active case-finding

passive case-finding (with or without case confirmation).

Table 4.

| a Trisomy 13 Counts and Prevalence by Maternal Age, 2006 to 2010 (Prevalence per 10,000 Live Births) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal age (years) | ||||||||

| State | <20 | 20–24 | 25–29 | 30–34 | 35–39 | 40+ | Total* | Notes |

| Live births | ||||||||

| Alaskap | <6 | <6 | <6 | <6 | <6 | <6 | 7 | 1 |

| . | . | . | . | . | . | 1.3 | ||

| Department of Defensep | 4 | 19 | 17 | 16 | 6 | 4 | 68 | 6 |

| 1.3 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.6 | 1.4 | 4.5 | 1.2 | ||

| Floridap | 5 | 20 | 21 | 20 | 21 | 13 | 100 | |

| 0.4 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.8 | 1.6 | 4.0 | 0.9 | ||

| Indianap | 0 | 5 | 4 | 8 | 5 | 1 | 23 | 10 |

| 0.0 | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.9 | 1.3 | 1.1 | 0.5 | ||

| Louisianaa | <5 | <5 | <5 | 0 | 0 | <5 | 9 | 12 |

| . | . | . | 0.0 | 0.0 | . | 0.7 | ||

| Minnesotaa | 0 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 11 | 16 |

| 0.0 | 2.1 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 2.3 | 2.3 | 0.9 | ||

| Nevadap | 1 | 4 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 12 | 23 |

| 0.3 | 1.0 | 0.0 | 0.7 | 0.5 | 1.9 | 0.6 | ||

| New Jerseyp | 1 | 2 | 2 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 17 | 22 |

| 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 1.3 | 0.3 | ||

| New Yorkp | 4 | 21 | 22 | 16 | 13 | 14 | 90 | |

| 0.5 | 0.8 | 0.7 | 0.5 | 0.7 | 2.8 | 0.7 | ||

| Vermontp | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 30 |

| 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.3 | ||

| West Virginiap | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 6 | 32 |

| 0.0 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.0 | 1.4 | 0.0 | 0.6 | ||

| Live births and stillbirths | ||||||||

| Arizonaa | 5 | 13 | 11 | 8 | 10 | 6 | 53 | 3 |

| 0.9 | 1.0 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 2.0 | 4.5 | 1.1 | ||

| Delawarea | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 5 |

| 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 2.5 | 0.0 | 0.3 | ||

| Illinoisp | 7 | 18 | 19 | 26 | 25 | 7 | 106 | 9 |

| 0.8 | 1.0 | 0.8 | 1.2 | 2.3 | 2.8 | 1.2 | ||

| Kansasp | 0 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 13 | 11 |

| 0.0 | 0.4 | 0.5 | 0.2 | 1.7 | 0.0 | 0.7 | ||

| Kentuckyp | 3 | 11 | 6 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 25 | |

| 0.8 | 1.3 | 0.7 | 0.2 | 0.9 | 1.9 | 0.9 | ||

| Marylandp | 3 | 2 | 5 | 11 | 9 | 10 | 40 | 14 |

| 0.9 | 0.3 | 0.5 | 1.1 | 1.6 | 7.0 | 1.0 | ||

| Massachusettsa | 2 | 4 | 5 | 2 | 8 | 5 | 26 | 13 |

| 0.9 | 0.7 | 0.5 | 0.2 | 1.1 | 2.9 | 0.7 | ||

| Michiganp | 4 | 10 | 16 | 14 | 5 | 5 | 57 | |

| 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.9 | 1.0 | 0.8 | 3.5 | 0.9 | ||

| Mississippip | 3 | 0 | 4 | 8 | 1 | 0 | 16 | |

| 0.8 | 0.0 | 0.7 | 2.4 | 0.7 | 0.0 | 0.7 | ||

| Missourip | 4 | 10 | 9 | 7 | 8 | 4 | 42 | 17 |

| 1.1 | 1.1 | 0.9 | 1.1 | 2.9 | 6.9 | 1.3 | ||

| Nebraskap | 1 | 4 | 9 | 5 | 2 | 1 | 22 | 20 |

| 0.9 | 1.2 | 2.1 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 3.8 | 1.6 | ||

| Ohiop | 0 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 12 | |

| 0.0 | 0.8 | 0.7 | 0.9 | 0.7 | 6.8 | 0.8 | ||

| Tennesseep | 3 | 9 | 11 | 5 | 6 | 1 | 35 | |

| 0.6 | 0.7 | 0.9 | 0.6 | 1.7 | 1.4 | 0.8 | ||

| Virginiap | 4 | 8 | 7 | 10 | 11 | 11 | 54 | 29 |

| 0.9 | 0.7 | 0.5 | 0.8 | 1.6 | 6.5 | 1.0 | ||

| Wisconsinp | 2 | 2 | 8 | 6 | 7 | 2 | 27 | |

| 0.7 | 0.3 | 0.8 | 0.7 | 2.0 | 2.7 | 0.8 | ||

| All pregnancy outcomes | ||||||||

| Arkansasa | 2 | 5 | 6 | 6 | 2 | 1 | 22 | 2 |

| 0.7 | 0.8 | 1.1 | 1.8 | 1.5 | 3.9 | 1.1 | ||

| Coloradop | 2 | 8 | 8 | 29 | 30 | 7 | 89 | 4 |

| 0.6 | 1.0 | 0.8 | 3.4 | 6.7 | 6.9 | 2.6 | ||

| Georgia/CDCa | 1 | 7 | 7 | 13 | 11 | 6 | 45 | 7 |

| 0.5 | 1.2 | 1.0 | 1.9 | 2.7 | 5.9 | 1.7 | ||

| Iowaa | 0 | 5 | 14 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 33 | 8 |

| 0.0 | 1.0 | 2.1 | 1.1 | 2.2 | 13.7 | 1.7 | ||

| North Carolinaa | 8 | 17 | 14 | 17 | 13 | 7 | 76 | 18 |

| 1.1 | 1.0 | 0.8 | 1.2 | 1.9 | 5.0 | 1.2 | ||

| New Hampshirea | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 5 | 21 |

| 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.5 | 1.0 | 9.3 | 0.7 | ||

| Oklahomaa | 1 | 9 | 11 | 3 | 5 | 2 | 31 | 24 |

| 0.3 | 1.0 | 1.4 | 0.7 | 2.7 | 5.2 | 1.2 | ||

| Puerto Ricoa | 3 | 6 | 4 | 6 | 8 | 3 | 30 | 25 |

| 0.7 | 0.8 | 0.7 | 1.6 | 5.1 | 8.7 | 1.3 | ||

| Rhode Islandp | 0 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 0 | 10 | 26 |

| 0.0 | 1.6 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 6.2 | 0.0 | 1.7 | ||

| South Carolinaa | 3 | 3 | 6 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 20 | 27 |

| 1.3 | 0.6 | 1.2 | 1.1 | 1.2 | 5.8 | 1.1 | ||

| Texasa | 15 | 46 | 40 | 35 | 34 | 21 | 191 | 28 |

| 0.7 | 1.0 | 0.9 | 1.1 | 2.2 | 6.4 | 1.2 | ||

| Utaha | 2 | 12 | 10 | 14 | 13 | 5 | 56 | |

| 1.1 | 1.7 | 1.1 | 2.3 | 6.0 | 11.9 | 2.1 | ||

| b Trisomy 13 Counts and Prevalence by Maternal Race/Ethnicity, 2006 to 2010 (Prevalence per 10,000 Live Births) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal race/ethnicity | |||||||

| State | White non-Hispanic |

Black non-Hispanic |

Hispanic | Asian and Pacific Islanders Non-Hispanic |

American Indian/ Alaska Native Non-Hispanic |

Total* | Notes |

| Live births | |||||||

| Alaskap | <6 | . | . | . | <6 | 7 | 1 |

| . | . | . | . | . | 1.3 | ||

| Department of Defensep | 40 | 19 | 7 | 1 | 0 | 68 | 6 |

| 1.1 | 2.3 | 1.1 | 0.4 | 0.0 | 1.2 | ||

| Floridap | 42 | 32 | 23 | 0 | 0 | 100 | |

| 0.8 | 1.3 | 0.7 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.9 | ||

| Indianap | 14 | 4 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 23 | 10 |

| 0.4 | 0.7 | 1.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.5 | ||

| Louisianaa | <5 | <5 | <5 | 0 | 0 | 9 | 12 |

| . | . | . | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.7 | ||

| Minnesotaa | 2 | 5 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 11 | 16 |

| 0.3 | 2.3 | 2.9 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.9 | ||

| Nevadap | 5 | 1 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 12 | 23 |

| 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.7 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.6 | ||

| New Jerseyp | 5 | 4 | 6 | 1 | 0 | 17 | 22 |

| 0.2 | 0.5 | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.3 | ||

| New Yorkp | 42 | 18 | 22 | 8 | 0 | 90 | |

| 0.7 | 0.9 | 0.8 | 0.6 | 0.0 | 0.7 | ||

| Vermontp | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 30 |

| 0.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.3 | ||

| West Virginiap | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 32 |

| 0.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.6 | ||

| Live births and stillbirths | |||||||

| Arizonaa | 16 | 4 | 24 | 7 | 2 | 53 | 3 |

| 0.8 | 2.1 | 1.2 | 4.5 | 0.7 | 1.1 | ||

| Delawarea | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 5 |

| 0.5 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.3 | ||

| Illinoisp | 70 | 19 | 12 | 4 | 0 | 106 | 9 |

| 1.5 | 1.3 | 0.6 | 0.9 | 0.0 | 1.2 | ||

| Kansasp | 4 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 13 | 11 |

| 0.3 | 0.0 | 0.6 | 3.5 | 0.0 | 0.7 | ||

| Kentuckyp | 18 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 25 | |

| 0.8 | 0.8 | 2.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.9 | ||

| Marylandp | 21 | 13 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 40 | 14 |

| 1.2 | 1.0 | 0.6 | 0.8 | 0.0 | 1.0 | ||

| Massachusettsa | 18 | 3 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 26 | 13 |

| 0.7 | 0.9 | 0.9 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.7 | ||

| Michiganp | 37 | 12 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 57 | |

| 0.9 | 1.1 | 0.7 | 0.9 | 0.0 | 0.9 | ||

| Mississippip | 6 | 9 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 16 | |

| 0.5 | 0.9 | 0.0 | 4.3 | 0.0 | 0.7 | ||

| Missourip | 26 | 8 | 6 | 2 | 0 | 42 | 17 |

| 1.1 | 1.6 | 3.3 | 2.6 | 0.0 | 1.3 | ||

| Nebraskap | 14 | 2 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 22 | 20 |

| 1.4 | 2.3 | 2.5 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1.6 | ||

| Ohiop | 10 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 12 | |

| 0.9 | 0.8 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.8 | ||

| Tennesseep | 17 | 12 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 35 | |

| 0.6 | 1.4 | 0.8 | 1.2 | 0.0 | 0.8 | ||

| Virginiap | 17 | 7 | 11 | 1 | 0 | 54 | 29 |

| 0.6 | 0.6 | 1.6 | 0.3 | 0.0 | 1.0 | ||

| Wisconsinp | 20 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 27 | |

| 0.8 | 0.9 | 0.9 | 0.7 | 0.0 | 0.8 | ||

| All pregnancy outcomes | |||||||

| Arkansasa | 16 | 4 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 22 | 2 |

| 1.2 | 1.0 | 0.9 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1.1 | ||

| Coloradop | 22 | 1 | 14 | 1 | 1 | 89 | 4 |

| 1.1 | 0.6 | 1.3 | 0.9 | 4.0 | 2.6 | ||

| Georgia/CDCa | 13 | 24 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 45 | 7 |

| 1.7 | 2.3 | 0.5 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1.7 | ||

| Iowaa | 24 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 33 | 8 |

| 1.4 | 1.2 | 2.5 | 2.1 | 0.0 | 1.7 | ||

| North Carolinaa | 34 | 23 | 14 | 2 | 1 | 76 | 18 |

| 1.0 | 1.5 | 1.3 | 1.0 | 1.1 | 1.2 | ||

| New Hampshirea | 3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 21 |

| 0.5 | 8.8 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.7 | ||

| Oklahomaa | 20 | 4 | 2 | 0 | 5 | 31 | 24 |

| 1.2 | 1.6 | 0.6 | 0.0 | 1.7 | 1.2 | ||

| Puerto Ricoa | 0 | 0 | 30 | 0 | 0 | 30 | 25 |

| . | . | 1.3 | . | . | 1.3 | ||

| Rhode Islandp | 2 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 10 | 26 |

| 0.6 | 4.0 | 2.5 | 3.9 | 0.0 | 1.7 | ||

| South Carolinaa | 8 | 10 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 20 | 27 |

| 0.8 | 1.7 | 0.6 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1.1 | ||

| Texasa | 63 | 23 | 94 | 10 | 0 | 191 | 28 |

| 1.1 | 1.3 | 1.2 | 1.7 | 0.0 | 1.2 | ||

| Utaha | 37 | 2 | 16 | 1 | 0 | 56 | |

| 1.8 | 7.8 | 3.7 | 1.1 | 0.0 | 2.1 | ||

Total includes unknown maternal age.

active case-finding

passive case-finding (with or without case confirmation).

Total includes unknown race.

active case-finding

passive case-finding (with or without case confirmation).

Figure 1.

Pooled prevalence (per 10,000 live births) of Down syndrome by maternal age (years).

Figure 3.

Pooled prevalence (per 10,000 live births) of trisomy 13 by maternal age (years).

Table 5 highlights the change in prevalence of Down syndrome, trisomy 18 and trisomy 13 by pregnancy outcome during this data reporting period (2006–2010) compared with an earlier reporting period (2000–2004), as published in the 2007 NBDPN Annual Report (NBDPN, 2007).

Table 5.

Change in Prevalencea of Down Syndrome, Trisomy 18, and Trisomy 13 by Pregnancy Outcomes

| State category by pregnancy outcomes |

Down syndrome (Trisomy 21) |

Trisomy 18 |

Trisomy 13 |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2000–2004b | 2006–2010 | PR(95% CI) | 2000–2004b | 2006–2010 | PR (95% CI) | 2000–2004b | 2006–2010 | PR (95% CI) | |

| Live births onlyc (n56) |

12.17 | 12.33 | 1.01 (0.97,1.06) | 1.23 | 1.41 | 1.15 (1.01,1.32) | 0.87 | 0.70 | 0.80 (0.67,0.96) |

| Live births and stillbirthsd (n59) |

11.96 | 12.84 | 1.07 (1.03,1.12) | 1.65 | 1.93 | 1.17 (1.05,1.30) | 0.85 | 0.97 | 1.13 (0.97,1.32) |

| All pregnancy outcomese (n59) |

13.36 | 14.44 | 1.08 (1.04,1.12) | 2.51 | 3.19 | 1.27 (1.17,1.38) | 1.25 | 1.42 | 1.14 (1.01,1.28) |

PR, prevalence ratio; CI, confidence intervals.

Prevalence per 10,000 live births.

Only states that reported for both periods were included. See footnotes 3–5 for the specific states. Source: NBDPN. Population-based Birth Defects Surveillance Data from Selected States, 2000–2004. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol. 2007 Dec;79(12):874–942.

States included Alaska, Florida, Indiana, New Jersey, New York, and West Virginia.

States included Arizona, Delaware, Illinois, Massachusetts, Michigan, Mississippi, Tennessee, Virginia, and Wisconsin.

States included Arkansas, Colorado, CDC/Georgia, Iowa, North Carolina, Oklahoma, Puerto Rico, Texas, and Utah.

DISCUSSION

Data Sources

Variability in the observed prevalence of trisomies across states could be due to true differences; however, other reasons may account for the differences observed, including case ascertainment methodology, ability of a surveillance system to capture all affected cases, and state variations for risk factors such as the distribution of maternal age in these populations. State programs vary in the number and type of data sources used to capture cases. The NBDPN data request stipulated that the birth defect counts provided for the report must be based on multiple data sources (not just vital records); however, the number of additional data sources can differ depending on state legislation, data access, and resources. Cragan and Gilboa (2009) noted that the inclusion of prenatal records from perinatal offices and maternal-fetal medicine departments increased the prevalence of chromosomal abnormalities by over 30%. Similarly, Tao et al. (2013) reported an increase of nearly 8% of all cases of chromosomal abnormalities for the reporting years 2008– 2010 in the New York surveillance registry by including cytogenetic laboratory reports.

Pregnancy Outcomes

In addition to data sources, another possible variation in the reported prevalence is the inclusion of different pregnancy outcomes in the case definition. Approximately one-third of the birth defects programs ascertain cases among live births only, one-third ascertain cases among live births and still births, and the remaining one-third capture cases for all pregnancy outcomes. Several factors affect a program’s decision to identify cases among pregnancy ending in nonlive births, such as program purpose, legal authority, and the availability of data. For example, a program designed to provide follow-up services for affected individuals might only ascertain cases among live births.

However, to understand the full impact of trisomies on the population, it is important to consider all pregnancy outcomes. The pooled prevalence from states with all pregnancy outcomes consistently show a higher prevalence, as presented in Figures 1–3, than the pooled prevalence from states with live births only or states with live births and stillbirths. Crider et al. (2008) reported a prevalence of trisomy 18 among live births only at 1.16 cases per 10,000 live births; among all pregnancy outcomes combined (live births, stillbirths, and elective terminations), the prevalence increased to 4.01 cases per 10,000 live births. Similarly, the prevalence of trisomy 13 changed from 0.63 per 10,000 live births for live births only to 1.57 per 10,000 live births for all pregnancy outcomes combined. Jackson et al. (2013) also reported a shift in the prevalence of Down syndrome from 11.5 per 10,000 live births for cases among live births only to 16.3 per 10,000 live births for cases among all pregnancy outcomes.

Prenatal Testing

Prenatal testing allows for a more accurate ascertainment of cases by surveillance systems, especially if they are diagnosed and captured in medical records. Prenatal diagnostic testing and elective termination have been shown to affect the live birth prevalence of Down syndrome (Mikkelsen, 1992; Cornel et al., 1993; Krivchenia et al., 1993; Bishop et al., 1997; Forrester and Merz, 1999) and of trisomies 18 and 13 (Crider et al., 2008). Noninvasive screening methods such as maternal protein serum assays and ultrasound have become more accurate and are being used with increasing frequency (Baker et al., 2004; Benn et al., 2004; Ekelund et al., 2008; Nakata et al., 2010). Additionally, a recent method of noninvasive prenatal testing that uses cell free fetal DNA collected from maternal blood has recently been used to screen for Down syndrome, trisomy 18, and trisomy 13 (Langlois et al., 2013). This method shows much promise as a screening tool and will likely result in a change in prevalence if early terminations are missed by states that capture all pregnancy outcomes. The data presented in this data report are not affected by cell free fetal DNA analysis because this screening tool was not commonly used/ employed until recently; however, as all noninvasive prenatal screening and testing methods increase in use, the effect on prevalence estimates derived from population-based birth defects surveillance systems will need to be monitored. The frequency with which prenatal detection results in elective pregnancy termination varies among states; opinions about and the use of elective pregnancy termination have been shown to differ by age, race/ethnicity, religion, socioeconomic status, marital status, and type of health insurance (Harris and Mills, 1985; Jones et al., 2010; Pazol et al., 2011).

Maternal Age

Maternal age is the most consistent risk factor associated with increased prevalence (Hecht and Hook, 1996; Mikkelsen, 1985). As expected, the prevalence consistently increases by maternal age as shown in Figures 1–3. However, surveillance systems that do not collect cases from all pregnancy outcomes are more likely to under-ascertain cases in the older maternal age groups than in the younger groups; this is more pronounced for trisomy 18 and 13 than for Down syndrome. The data suggest that pregnancy loss (e.g., stillbirths, terminations) is more common among advanced maternal age groups. Previous studies have shown an increased risk of stillbirths as well as increased usage of prenatal testing in women 35 years and older (Reddy et al., 2006; Crider et al., 2008; Jackson et al., 2011).

The maternal age distribution in the United States has shifted toward older ages over the past few decades (Martin et al., 2012); however, during the birth period included in this report (2006–2010), this trend has remained relatively stable. Although advanced maternal age is a known risk factor for trisomy, advanced paternal age has not been observed to be an independent risk factor after adjusting for maternal age (Janerich and Bracken, 1986; De Souza and Morris, 2010).

Maternal Race/Ethnicity

There appears to be modest variation in the prevalence of trisomy 13 and 18 by race/ethnicity, but previous reports have not been consistent. Crider et al. (2008) found the highest prevalence for each among non-Hispanic whites, but others found a lower or no difference in prevalence among non-Hispanic whites compared with Hispanics and non-Hispanic blacks (Canfield et al., 2006; Kucik et al., 2012). Variation in prevalence of Down syndrome by race/ethnicity has been more consistently reported. The prevalence among Hispanics is significantly higher than among non-Hispanic whites, particularly among births to mothers 35 years or older (CDC, 1994; Canfield et al., 2006; Agopian et al., 2012; Kucik et al., 2012), while non-Hispanic black women have the lowest observed prevalence. These differences may be related to differential use of prenatal diagnostic services (Kupper-mann et al., 1996, 2006). Jackson et al. (2013) suggest that biological causes, such as maternal age, as well as social factors, such as attitudes regarding elective termination and access to care, might contribute to the race/ethnicity differences observed in the prevalence of Down syndrome.

Trends in Prevalence and Survival

Information on trends in prevalence of trisomy 18 and 13 is sparse (Crider et al., 2008), but the increasing prevalence of Down syndrome has been documented previously (Shin et al., 2009; Cocchi et al., 2010). This report provides evidence that this trend continues for Down syndrome, trisomy 18, and trisomy 13. Compared with birth prevalence estimates reported in the 2007 Annual report of the NBDPN, an increase in the pooled prevalence was noted for all three trisomy groups as reported by state programs that included all pregnancy outcomes and by those that reported live births and still births (Table 5) (NBDPN, 2007). The pooled prevalence among states that reported only live births increased for Down syndrome and trisomy 18 but declined slightly for trisomy 13. From 1979 to 2003, Shin et al. (2009) reported an increase in the live birth prevalence for Down syndrome from 9.0 to 11.8 per 10,000 live births, so the live birth prevalence in this report supports a continuing increase.

Although trisomy 13 and 18 are nearly always fatal (Rasmussen et al., 2003; Vendola et al., 2010), the improved survival of those born live with Down syndrome has been previously documented (Kucik et al., 2013; Zhu et al., 2013) with the most recent 1-year survival probability (birth period 1997–2003) estimated as high as 94% (Kucik et al., 2013). The greatest survival improvement has been observed among those individuals with Down syndrome born of low birth weight or with a co-occurring congenital heart defect (Kucik et al., 2013; Zhu et al., 2013), which is the leading cause of death among infants and children with Down syndrome (Shin et al. 2007; Zhu et al., 2013).

CONCLUSIONS

This data report provides state-specific birth defects data from 41 population-based birth defects surveillance programs in the United States and continues to be an important data source to understand the impact of these conditions. The focus on trisomy conditions highlights continuing trends and underscores the importance of accounting for differences in ascertainment and reporting practices to fully understand the variation in prevalence by state. With the increasing prevalence of trisomies and improved survival of affected individuals, this report serves as an important notice to clinicians, health officials, and health care planners of the growing public health importance of trisomies; additionally, it suggests the need for more research on the role of prenatal detection in improving postnatal health and health service planning that addresses the lifetime needs of a growing population.

Supplementary Material

Figure 2.

Pooled prevalence (per 10,000 live births) of trisomy 18 by maternal age (years).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the state birth defects surveillance programs that submitted data for this report: Alaska Birth Defects Registry; Arkansas Reproductive Health Monitoring System; Arizona Birth Defects Monitoring Program; California Birth Defects Monitoring Program; Colorado Responds To Children With Special Needs; Delaware Birth Defects Surveillance Project; United State Department of Defense (DoD) Birth and Infant Health Registry; Florida Birth Defects Registry; Metropolitan Atlanta Congenital Defects Program; Iowa Registry For Congenital and Inherited Disorders; Illinois Adverse Pregnancy Outcomes Reporting System; Indiana Birth Defects & Problems Registry; Kansas Birth Defects Information System; Kentucky Birth Surveillance Registry; Louisiana Birth Defects Monitoring Network; Massachusetts Center for Birth Defects Research and Prevention; Maryland Birth Defects Reporting and Information System; Maine Birth Defects Program; Michigan Birth Defects Registry; Minnesota Birth Defects Information System; Missouri Birth Defects Surveillance System; Mississippi Birth Defects Registry; North Carolina Birth Defects Monitoring Program; North Dakota Birth Defects Monitoring System; Nebraska Birth Defects Registry; New Hampshire Birth Conditions Program; New Jersey Special Child Health Services Registry; Nevada Birth Outcomes Monitoring System; New York State Congenital Malformations Registry; Ohio Connections for Children with Special Needs; Oklahoma Birth Defects Registry; Puerto Rico Birth Defects Surveillance and Prevention System; Rhode Island Birth Defects Program; South Carolina Birth Defects Program; Tennessee Birth Defects Registry; Texas Birth Defects Epidemiology and Surveillance Branch; Utah Birth Defect Network; Virginia Congenital Anomalies Reporting and Education System; Vermont Birth Information Network; Washington State Birth Defects Surveillance System; Wisconsin Birth Defects Registry; and West Virginia Congenital Abnormalities Registry, Education and Surveillance System. The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Footnotes

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article.

REFERENCES

- Agopian AJ, Marengo LK, Mitchell LE. Predictors of trisomy 21 in the offspring of older and younger women. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol. 2012;94:31–35. doi: 10.1002/bdra.22870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker D, Teklehaimanot S, Hassan R, Guze C. A look at a Hispanic and African American population in an urban prenatal diagnostic center: referral reasons, amniocentesis acceptance, and abnormalities detected. Genet Med. 2004;6:211–218. doi: 10.1097/01.gim.0000132684.94642.a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benn PA, Egan JF, Fang M, Smith-Bindman R. Changes in the utilization of prenatal diagnosis. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;103:1255–1260. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000127008.14792.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bishop J, Huether CA, Torfs C, et al. Epidemiologic study of Down syndrome in a racially diverse California population, 1989–1991. Am J Epidemiol. 1997;145:134–147. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CDC. Down syndrome prevalence at birth-United States, 1983–1990. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1994;43:617–622. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canfield MA, Honein MA, Yuskiv N, et al. National estimates and race/ethnic-specific variation of selected birth defects in the United States, 1999–2001. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol. 2006;76:747–756. doi: 10.1002/bdra.20294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cocchi G, Gualdi S, Bower C, et al. International trends of Down syndrome 1993–2004: Births in relation to maternal age and terminations of pregnancies. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol. 2010;88:474–479. doi: 10.1002/bdra.20666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornel MC, Breed AS, Beekhuis JR, et al. Down syndrome: effects of demographic factors and prenatal diagnosis on the future livebirth prevalence. Hum Genet. 1993;92:163–168. doi: 10.1007/BF00219685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cragan JD, Gilboa SM. Including prenatal diagnoses in birth defects monitoring: experience of the Metropolitan Atlanta Congenital Defects Program. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol. 2009;85:20–29. doi: 10.1002/bdra.20508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crider KS, Olney RS, Cragan JD. Trisomies 13 and 18: population prevalences, characteristics, and prenatal diagnosis, metropolitan Atlanta, 1994–2003. Am J Med Genet A. 2008;146:820–826. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.32200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Souza E, Morris JK EUROCAT Working Group. Case-control analysis of paternal age and trisomic anomalies. Arch Dis Child. 2010;95:893–897. doi: 10.1136/adc.2009.176438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekelund CK, Jorgensen FS, Petersen OB, et al. Impact of a new national screening policy for Down’s syndrome in Denmark: population based cohort study. BMJ. 2008;337:a2547. doi: 10.1136/bmj.a2547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forrester MB, Merz RD. Prenatal diagnosis and elective termination of Down syndrome in a racially mixed population in Hawaii, 1987–1996. Prenat Diagn. 1999;19:136–141. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris RJ, Mills EW. Religion, values and attitudes toward abortion. J Sci Study Relig. 1985;24:119–236. [Google Scholar]

- Hecht CA, Hook EB. Rates of Down syndrome at livebirth by one-year maternal age intervals in studies with apparent close to complete ascertainment in populations of European origin: A proposed revised rate schedule for use in genetic and prenatal screening. Am J Med Genet. 1996;62:376–385. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-8628(19960424)62:4<376::AID-AJMG10>3.0.CO;2-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson JM, Crider KS, Rasmussen SA, et al. Trends in cytogenetic testing and identification of chromosomal abnormalities among pregnancies and children with birth defects, Metropolitan Atlanta, 1968–2005. Genet Med. 2011;158A:116–123. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.34385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson JM, Crider KS, Rasmussen SA, et al. Frequency of prenatal cytogenetic diagnosis and pregnancy outcomes by maternal race-ethnicity and the effect on the prevalence of trisomy 21, Metropolitan Atlanta, 1996–2005. Am J Med Genet. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.36247. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones RK, Finer LB, Singh S. Characteristics of U.S. abortion patients, 2008. New York, NY: Guttmacher Institute; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Janerich DT, Bracken MB. Epidemiology of trisomy 21: a review and theoretical analysis. J Chronic Dis. 1986;39:1079–1093. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(86)90141-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kucik JE, Shin M, Siffel C, et al. Congenital Anomaly Multistate Prevalence and Survival Collaborative. Trends in survival among children with Down syndrome in 10 regions of the United States. Pediatrics. 2013;131:e27–e36. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-1616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kucik JE, Alverson CJ, Gilboa SM, Correa A. Racial/ethnic variations in the prevalence of selected major birth defects, metropolitan Atlanta, 1994–2005. Public Health Rep. 2012;127:52–61. doi: 10.1177/003335491212700106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krivchenia E, Huether CA, Edmonds LD, et al. Comparative epidemiology of Down syndrome in two United States population, 1970–1989. Am J Epidemiol. 1993;137:815–828. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuppermann M, Gates E, Washington AE. Racial-ethnic differences in prenatal diagnostic test use and outcomes: Preferences, socioeconomics, or patient knowledge? Obstet Gynecol. 1996;87:675–682. doi: 10.1016/0029-7844(96)00017-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuppermann M, Learman LA, Gates E, et al. Beyond race or ethnicity and socioeconomic status: predictors of prenatal testing for Down syndrome. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;107:1087–1097. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000214953.90248.db. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langlois S, Brock JA, Genetics Committee et al. Current status in non-invasive prenatal detection of Down syndrome, trisomy 18, and trisomy 13 using cell-free DNA in maternal plasma. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2013;35:177–181. doi: 10.1016/S1701-2163(15)31025-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason CA, Kirby RS, Sever LE, Langlois PH. Prevalence is the preferred measure of frequency of birth defects. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol. 2005;73:690–692. doi: 10.1002/bdra.20211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin JA, Hamilton BE, Ventura SJ, et al. Births: Final data for 2010. National Center for Health Statistics; 2012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikkelsen M. Down anomaly: new research of an old and well known syndrome. In: Berg K, editor. Medical genetics: past, present, future. New York: Alan R. Liss; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Mikkelsen M. The impact of prenatal diagnosis on the incidence of Down syndrome in Denmark. Birth Defects Orig Artic Ser. 1992;28:44–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakata N, Wang Y, Bhatt S. Trends in prenatal screening and diagnostic testing among women referred for advanced maternal age. Prenat Diagn. 2010;30:198–206. doi: 10.1002/pd.2434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NBDPN. Population-based birth defects surveillance data from selected states, 2000–2004. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol. 2007;79:874–942. doi: 10.1002/bdra.20428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker SE, Mai CT, Canfield MA, et al. Updated national birth prevalence estimates for selected birth defects in the United States, 2004–2006. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol. 2010;88:1008–1016. doi: 10.1002/bdra.20735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pazol K, Zane S, Parker WY, et al. Abortion surveillance - United States, 2007. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2011;60:1–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen SA, Wong LY, Yang Q, et al. Population-based analyses of mortality in trisomy 13 and trisomy 18. Pediatrics. 2003;111(Pt 1):777–784. doi: 10.1542/peds.111.4.777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy UM, Ko CW, Willinger M. Maternal age and the risk of stillbirth throughout pregnancy in the United States. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;195:764–770. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2006.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherman SL, Allen EG, Bean LH, Freeman SB. Epidemiology of Down syndrome. Ment Retard Dev Disabil Res Rev. 2007;13:221–227. doi: 10.1002/mrdd.20157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin M, Besser LM, Kucik JE, et al. Congenital anomaly multistate prevalence and survival collaborative. Prevalence of Down syndrome among children and adolescents in 10 regions of the United States. Pediatrics. 2009;124:1565–1571. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-0745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin M, Kucik JE, Correa A. Causes of death and case fatality rates among infants with down syndrome in metropolitan Atlanta. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol. 2007;79:775–780. doi: 10.1002/bdra.20414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tao Z, Wang Y, Dicesare DK, et al. Electronic clinical laboratory reports as a source for ascertaining and confirming chromosomal anomalies reported to the New York State Congenital Malformations Registry. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2013;19:E17–E24. doi: 10.1097/PHH.0b013e31825739e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vendola C, Canfield M, Daiger SP, et al. Survival of Texas infants born with trisomies 21, 18, and 13. Am J Med Genet A. 2010;152A:360–366. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.33156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu JL, Hasle H, Correa A, et al. Survival among people with Down syndrome: a nationwide population-based study in Denmark. Genet Med. 2013;15:64–69. doi: 10.1038/gim.2012.93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.