Abstract

Consumers with serious mental illness (N=166) enrolling in two community-based mental health programs, a vocational Program of Assertive Community Treatment and a clubhouse certified by the International Center for Clubhouse Development (ICCD), were asked about their interest in work. About one third of the new enrollees expressed no interest in working. Equivalent supported employment services were then offered to all participants in each program. Stated interest in work and receipt of vocational services were statistically significant predictors of whether a person would work and how long it would take to get a job. Two thirds of those interested in work and half of those with no initial interest obtained a competitive job if they received at least one hour of vocational service. Once employed, these two groups held comparable jobs for the same length of time. These findings demonstrate the importance of making vocational services continuously available to all people with serious mental illness, and the viability of integrating these services into routine mental health care.

Keywords: competitive employment, PACT, clubhouse, work interest

Over the past two decades, services integration and coordination have become a focus for both mental health system administrators and the federal government (Bickman, 1996; Goldman, Rosenberg, & Manderscheid, 1988). Vocational rehabilitation, historically considered an auxiliary service in mental health treatment planning (Noble, Honberg, Hall, & Flynn, 1997), is now evolving into a blend of mental health and vocational services that offers a naturally occurring contrast of two competing approaches to services integration. Supported employment services for people with serious mental illness can be generally classified as either (1) interventions integrated at the system or agency level (across programs) in which staff from a vocational program meet regularly with staff from mental health programs to discuss client needs and service plans, or (2) interventions integrated at the program or staff level (within programs) in which vocational services are routinely available along with mental health services. When employment services are integrated within a program, they may be provided by vocational specialists who work side by side on a daily basis with the same program’s mental health staff, or they may be further integrated at the staff level, wherein generalist staff routinely provide a variety of community supports including vocational rehabilitation.

Specialized vocational programs that routinely collaborate with clinical or case management programs include Boston University’s Choose-Get-Keep program (Danley & Anthony, 1987) and its derivations (Rimmerman, Botuck, & Levy, 1995); job clubs (Jacobs, Collier, & Wissusik, 1992); the Individual Placement and Support model (IPS) (Drake, 1998); and a variety of generic supported employment interventions (e.g., Gervey, Parrish, & Bond, 1995). Mental health programs that have specialist vocational staff include some mobile case management teams (Okapaku, Anderson, Sibulkin, Butler, & Bickman, 1997; Mowbray et al., 1994), Family-aided Assertive Community Treatment (FACT) (McFarlane, Stastny, Deakins, & Dushay, 1995), and several well-known multi-service programs, such as Portals in California (Brekke, Ansel, Long, Slade, & Weinstein, 1999), the Village in California (Chandler, Levin, & Barry, 1999), and Thresholds in Chicago (Cook & Razzano, 1992). Mental health programs that rely on generalist staff to provide vocational services in tandem with mental health services include the Program of Assertive Community Treatment (PACT) (Stein & Test, 1980; Russert & Frey, 1991) and clubhouses based on Fountain House in New York (Beard, Propst, & Malamud, 1982; Macias, Jackson, Schroeder, & Wang, 1999).

Most supported employment programs utilize a similar set of support strategies, such as job development and on-the-job training (Trach, 1990; Bond, Picone, Mauer, Fishbein, & Stout, 2000), but there are important differences between programs in how these services are offered. Enrollment in a specialized employment program requires a consumer to express interest in obtaining paid work. Mental health staff may assess work readiness or encourage enrollment, but ultimately the consumer must say he or she is ready to look for work. Newer models of supported employment screen for work interest through mandatory attendance at two to four induction sessions (Bebout, Becker, & Drake, 1998; Drake, Becker, & Anthony, 1994). This focus of program resources on highly motivated consumers reduces the chance that employment services will be wasted on persons not yet ready to work (Bond, Drake, Becker, & Mueser, 1999). By contrast, programs that provide both employment and mental health services have no formal application process for obtaining vocational help. Program staff can informally offer practical help and initiate a job search any time the consumer seems willing. This allows consumers to take tentative steps toward employment without public commitment. This simple difference in procedures has far-reaching implications.

WORK INTEREST AS A CONSUMER SELECTION TOOL

Research on work motivation and serious mental illness has addressed disincentives (Noble, 1998), disability accommodations (Gates, Akabas, & Oran-Sabia, 1998), stigma (Diksa & Rogers, 1996), job preferences (Becker, Drake, Farabaugh & Bond, 1996), and pay (Bell, Milstein, & Lysaker, 1993), but has not yet addressed more directly intent to seek work and its impact on eventual employment. Psychological theories of planned behavior (Ajzen, 1996) and goal striving (Gollwitzer, 1999) suggest that intent will lead to employment when an individual is consciously focused on work through practical planning and firm determination. If almost all people with serious mental illness want paid work and have the self-confidence to state their interest and the initiative to seek help in finding a job, providing vocational services through specialized employment programs may well be fair and efficient.

On the other hand, if large numbers of people with serious mental illness who can work lack the initiative to enroll in an employment program, then we need to consider the value of routinely integrating employment supports into mental health programs. Advocates for the integration of employment services into mental health programs emphasize the therapeutic value of work (Black, 1988; Frey, 1994; Harding, Strauss, Hafez, & Lieberman, 1987; Rogers, 1995), as well as the disabling effects of unemployment (Dooley, Catalano, & Wilson, 1994), and argue that work is an inherent right of treatment (Strauss, Harding, & Silverman, 1988). Restricting vocational services to only a portion of the population of persons with psychiatric disabilities, who are already willing to work, challenges such a zero-exclusion philosophy (Bybee, Mowbray, & McCrohan, 1996). If individuals are reluctant to work simply because they lack sufficient self-confidence or experience, then a critical component of vocational services should be the cultivation of a decision to work (Cook & Razzano, 2000). Withholding vocational supports from mental health service consumers until they express interest in work may rob them of an opportunity for life improvement.

Almost all evaluative research on vocational rehabilitation has been on system-integrated or agency-integrated programs, primarily the Choose-Get-Keep program developed by Boston University (BU) (Danley & Anthony, 1987) and the model of IPS developed at Dartmouth Medical School (Bond, Drake, Mueser, & Becker, 1997). Although a few program-integrated vocational interventions have published descriptive reports of employment rates and services provision (Chandler et al., 1999; Macias, Barreira, Alden, & Boyd, 2001), results from controlled effectiveness studies are lacking. Comparison studies that do exist have compared strong, supported employment programs to mental health programs with relatively weak vocational components (e.g., Drake, Becker, Biesanz, Torrey, McHugo, & Wyzik, 1994; Drake, Becker, Biesanz, Wyzik, & Torrey, 1996; Drake et al., 1999) or to vocational programs with an educational or skill training emphasis (e.g., Drake, McHugo, Becker, Clark, & Anthony, 1996). Mode of service delivery and service intensity have both varied at once in these studies, making the impact of programmatic differences indistinguishable from dosage effects. There is still no clear evidence concerning whether it is better to integrate high-quality supported employment and mental health services across different programs or within the same multi-service program.

The present study offers an opportunity to answer three pertinent research questions: (1) How prevalent is work interest within a community-based sample of persons with serious mental illness? (2) Is a stated interest in work an indicator of greater receptivity to vocational services? and (3) Is a stated interest in work predictive of actual employment?

METHOD

This study was conducted as part of the Employment Intervention Demonstration Program (EIDP) of the federal Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA). The eight-project EIDP was funded for a period of five years (1995–2000) and included a coordinating center as well as a common data collection protocol. The present quasi-experimental research study was conducted with data from only the Worcester, Massachusetts, EIDP project when it was 2.5 years into service funding. Within the Massachusetts EIDP, consumers with serious mental illness were randomly assigned to one of two widely implemented service models: a Program of Assertive Community Treatment (PACT) or a clubhouse program certified by the International Center for Clubhouse Development, Inc. The focus of the present study is on a shared characteristic of these two programs (i.e., staff-level integration of vocational services), rather than on their operational differences. Because the current findings address critical policy issues, it was deemed appropriate to pool data across the two experimental interventions for work interest versus no work interest consumers. Early intervention outcomes are presented only to substantiate that the findings were not limited to just one or the other experimental condition. Conclusions about the relative effectiveness of PACT versus clubhouse should wait until the experimental outcomes are available for a common 24–month point-of-service study period.

The Vocational Interventions

The PACT Model

The Program of Assertive Community Treatment (Stein & Test, 1980; Test & Stein, 1980; Test et al., 1997) is an intensive mobile treatment team providing a full range of direct clinical and rehabilitation services in consumers’ homes or in other locations within the community. The PACT approach utilizes a multi-disciplinary team of generalist staff from a variety of disciplines, including psychiatrists, clinical psychologists, registered nurses, social workers, case managers, vocational specialists, and substance abuse specialists (Russert & Frey, 1991). The PACT at Community Healthlink, Inc., in Worcester, Massachusetts, was created by Leonard Stein, M.D., and Jana Frey, Ph.D., of Madison, Wisconsin. Together with Dr. Mary Ann Test, Dr. Stein shaped the original PACT program in Madison 20 years ago. Dr. Frey integrated supported employment into PACT in the 1980s and, as Director of the original PACT at Mendota Mental Health Center in Madison, now provides national training in the vocationally integrated version of PACT. Operational and organizational fidelity of the Worcester PACT to the vocationally integrated PACT model was verified on an annual basis through site visits by both Dr. Frey and Dr. Gary Bond during the project’s start-up phase, and by Dr. Frey on an annual basis thereafter. Dr. Bond also verified that the Worcester PACT team was delivering supported employment services of the same quality as those provided by other models of supported employment (e.g., choice in jobs, rapid job search, assertive outreach, follow-along supports), even though the team did not operate in the same way as agency-integrated employment programs (e.g., vocationally trained staff did not function as a vocational unit distinct from other PACT staff, vocationally trained staff provided substantial non-vocational support services, other PACT staff provided employment supports, and the program did not screen for work interest).

The ICCD Clubhouse Model

The Clubhouse model (Anderson, 1998; Beard, 1987) is a facility-based intervention designed to offer persons with serious mental illness membership in a mutually supportive community. A defining aspect of the Clubhouse model is the “work-ordered day” (Beard et al., 1982), in which members and staff work side by side Monday through Friday to perform voluntary work essential to the clubhouse. On weekends, evenings, and holidays, members and staff plan and participate in social activities. All certified clubhouses provide comprehensive case management by trained staff and an array of services, including supported education, supported housing, help with entitlements, transportation, supportive counseling, and medication oversight. Certified clubhouses also provide supported employment services, such as rapid job searches, job development, on-site job training, and follow-along job support. Regardless of what path a consumer’s recovery takes, the clubhouse is available as a lifetime source of support and companionship (Macias & Rodican, 1997). The Clubhouse program in Worcester, Massachusetts, Genesis Club, Inc., was continuously certified by the International Center for Clubhouse Development (ICCD), confirming its adherence to the International Standards for Clubhouse Programs (Propst, 1982; Macias, Propst, Rodican, & Boyd, in press). Genesis Club is also representative of certified clubhouses, with operational characteristics and outcomes close to the averages established by the ICCD Benchmarks for Clubhouse Programs (Macias et al., 2001).

Research Participants

The study sample consisted of all active research participants enrolled in the two Worcester experimental programs (N=166). Admission criteria for the project were (a) age 18 or older, (b) a DSM-IV diagnosis of serious mental illness, (c) absence of severe mental retardation (IQ>65), and (d) being currently unemployed. The EIDP sample was recruited from within and around the city of Worcester, Massachusetts. The recruitment plan was designed by the project’s Advisory Council, composed of representatives from the National Alliance for the Mentally Ill (NAMI), consumer advocacy groups, the regional Department of Mental Health, and intervention service providers. A strong effort was made to recruit participants from diverse sources in order to obtain a heterogeneous and representative sample of people with serious mental illness. Referral sources included families, advocacy organizations, mental health programs, the department of mental health, treatment and correctional facilities, and homeless shelters, as well as self-referrals in response to radio and newspaper advertising.

Attrition in the EIDP Project

Of the 177 clients entering the research project, 11 were lost to follow-up within the first three months of the study: Two refused all project participation, 5 moved out of state, 3 died, and 1 could never be contacted after the baseline interview. The sample for this midpoint analysis had 166 consumers, 86 enrolled in PACT and 80 in the Clubhouse program. The 11 participants omitted from the present analysis were similar to the study sample on background variables and work history, except that they all were Caucasian.

Participant Length of Time in Study

The present analyses were conducted about 2.5 years after start-up of project services. Enrollment in the PACT and Clubhouse programs averaged five participants per program each month, in keeping with the PACT model standards. At this midpoint in the 5-year SAMHSA project, the 166 study participants had been enrolled for an average of about 1.3 years (M=468 days). The range in project tenure was from 2.4 months to 2.4 years. The mean length of time in the project was about the same for participants interested (M=454.9 days; SD=213.2) and not interested (M=497.9 days; SD=245.3) in paid work, and was equivalent for the two experimental conditions.

Data Sources and Research Instruments

Data sources for the present analysis were records from previous service providers, participant baseline interviews, and experimental agency daily service logs and records of consumer employment. Variables retrieved from service records were diagnosis and history of substance abuse; interviews provided reports of work history, medications, and financial status, as well as participant ratings of quality of life (Lehman, Kernan, & Postrado, 1997) and self-esteem (Rosenberg, 1979). The Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) (Kay, Fiszbein, & Opler, 1987) was administered by interviewers trained by Lewis Opler, M.D., a close collaborator on the development of the PANSS. Interviewers had high inter-rater reliability for the positive (r=.95), negative (r=.89), and general (r=.94) PANSS subscales (Trumbetta, McHugo, & Drake, 1997).

Interest in work was measured by a single question asked verbally in all baseline research interviews: “Are you currently interested in working?” A response was coded as 1 if the participant reported interest in getting a job, or 0 if he or she did not want to work or was uncertain. The interviewer clarified that the question pertained to only paid employment if the consumer expressed interest in an avocation or volunteering. The question was asked immediately after a “select all that apply” item documenting current work status: employed, leave of absence, looking for work, keeping house, school, volunteer work, training, or unable to work.

RESULTS

I. How Prevalent is Work Interest in a Sample of Persons with Serious Mental Illness?

Sample Description

About half (52%) of the study participants were diagnosed as having a schizophrenia spectrum disorder. The majority (61%) had a documented history of serious substance abuse, and a third (32%) did not have a high school diploma. Two thirds (69%) received social security benefits. The sample was balanced in regard to gender (55% male), and the average age was 39 years. The residential status of participants at baseline reflects diversity in recruitment, with 56% living independently, 8% in supported or assisted living housing, 16% living as a dependent with their family, and 15% hospitalized. A few participants were in jail or homeless. Nearly all (96%) had worked for pay at some time in their lives, with the length of unemployment immediately preceding entry into the project varying from less than a month to 27 years (M=5 years). Overall, the study sample was representative of the Worcester Area Department of Mental Health population statistics in regard to demographics (e.g., 21% ethnic minority), and monthly income (M=$565).

Prevalence of Work Interest

At the time of enrollment, 30% of the study sample expressed no interest in getting a job. This percentage was about the same for both PACT (26%) and Clubhouse (34%) conditions. The vast majority of consumers who did not express an interest in working gave a definite “no” (n=40); only a few were uncertain about whether they wanted to work (n=9). Interest and no-work-interest groups were similar in regard to all background characteristics except ethnicity; a higher percentage of ethnic minority enrollees lacked interest in obtaining work.

II. Is a Stated Interest in Work an Indicator of Greater Receptivity to Vocational Services?

The majority of both work-interest and no-work-interest participants received employment supports (79% and 65%, respectively). Participants who expressed no interest in work at enrollment, but did take a competitive job, received more vocational services than participants who had expressed interest (M=39.09 vs. 23.88 hours)—about a third more preparatory hours (help with interview, resume or job hunting, vocational counseling) (M=17.13 vs. 10.11), and a third more on-the-job hours (M=21.96 vs. 13.77). These mean scores did not differ significantly for PACT and Clubhouse.

III. Is a Stated Interest in Work Predictive of Actual Employment?

Relation of Work Interest to Job Placement Rate

The present study counted as employment only those jobs that met the federal definition of competitive work, that is, jobs located in integrated, mainstream settings that paid at least minimum wage (Department of Labor, 1998; Workforce Investment Act, 1998). All independent, supported, and transitional employment fit this federal definition (Macias et al., in press) and had the same wages, hours, and employer supervision as jobs held by non-disabled coworkers. As Table 1 shows, a greater percentage of work-interest than no-work-interest participants obtained a competitive job during the study period (51.3% vs. 28.6%), with an overall intent-to-treat employment rate of 44.6% when service tenure averaged a little more than a year. The employment rate was 62.7% for the 110 participants who received at least one hour of vocational service, the definition of “engagement” suggested by Bybee and colleagues (1996). A job placement rate more equivalent to published rates for employment programs providing only vocational services would be the percentage employed of all work-interest consumers who engaged in vocational services. This employment rate was 67.5%, and it was comparable for PACT and Clubhouse (66% and 70%, respectively). However, nearly half (48.1%) of participants in both PACT and Clubhouse who had not expressed initial work interest did take a competitive job once they engaged in vocational services.

TABLE 1.

Employment Outcomes for Total Sample

| Variables | Interest (n=117) | No Interest (n=49) | Total (N=166) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Percentages | % (n) | % (n) | % (n) |

| Days in Project | |||

| Less than one year | 35.9 (42) | 26.5 (13) | 33.1 (55) |

| One year to 18 mo. | 27.4 (32) | 28.6 (14) | 27.7 (46) |

| 18 months or longer | 36.8 (43) | 44.9 (22) | 39.2 (65) |

| Received Vocational Services | |||

| Any vocational services | 78.6 (92) | 65.3 (32) | 74.7 (124) |

| Engaged (1 hour service) | 70.9 (83) | 55.1 (27) | 66.3 (110) |

| Job Placement Rates | |||

| All study participants | 51.3 (60/117) | 28.6 (14/49) | 44.6 (74/166) |

| Vocationally engaged | 67.5 (56/83) | 48.1 (13/27) | 62.7 (69/110) |

Relation of Work Interest to Time to First Job

Table 2 reports work performance for all employed participants. Length of time from project enrollment to first job averaged 146 days for work-interest participants and 208 days for participants without initial work interest. Likewise, mean length of time between first vocational service and job placement was 95 days for work-interested participants versus 145 days for those with no initial interest in work. Overall, about half of all employed participants began work within 3.5 months (Md=104.50 days) of enrollment, and two thirds began a job within 6 months. There were no statistically significant differences between PACT and Clubhouse programs on any of these time-to-first-job variables.

TABLE 2.

Work Outcomes for Employed Participants

| Variables | Interest (n=60) M (SD) Md |

No Interest (n=14) M (SD) Md |

Total (n=74) M (SD) Md |

|---|---|---|---|

| Days in project | 552.60 (190.10) 583.00 |

642.71 (238.00) 734.50 |

569.65 (201.39) 608.50 |

| Total days to job | 146.13 (134.12) 94.50 |

207.64 (160.01) 166.00 |

157.77 (140.31) 104.50 |

| Days from first voc service to job | 95.14 (116.14) 42.00 |

145.07 (164.40) 81.00 |

104.85 (127.17) 49.50 |

| Total days of work | 182.13 (164.38) 115.00 |

232.50 (173.43) 234.50 |

191.66 (166.10) 120.00 |

| Days per job | 109.77 (101.88) 75.30 |

147.90 (137.63) 90.70 |

116.98 (109.49) 77.30 |

| Days on longest job | 138.55 (127.63) 95.00 |

179.50 (138.49) 149.50 |

146.30 (129.78) 99.00 |

| Total hours of work | 501.42 (662.81) 213.72 |

739.32 (561.63) 885.50 |

543.78 (648.82) 227.96 |

Note: Medians are included because the variables are skewed.

Statistical Analysis of Work Interest as a Predictor of Time to First Job

Analyzing length of time until the first job within a sample of both employed and unemployed participants introduces statistical problems that can be dealt with by survival analysis (e.g., Klein & Moeschberger, 1997; Singer & Willett, 1991), also known as event history analysis (Allison, 1984; Petersen, 1995). Specifically, some participants have indeterminant values for days to first job because they did not obtain work during the study period; these right censored values are handled by survival analysis.

Six participants were dropped from the survival analysis because they had missing values on one or more of the predictor variables used in the Cox regression model (Figure 1). The dropped participants were evenly split with respect to gender, ethnic status, and diagnosis; 4 expressed no interest in work at the time of enrollment and 2 obtained employment during the study.

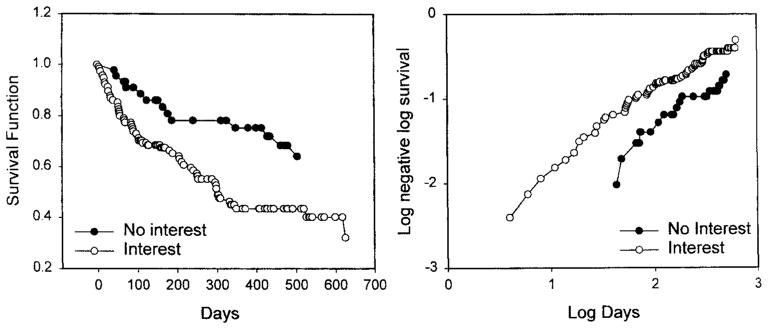

FIGURE 1. Estimated Survival Functions and the Log of the Negative Log Estimated Survival Functions.

The left panel shows estimated survival functions stratified by expressed interest in work. The right panel shows the log of the negative log estimated survival functions stratified by expressed interest in work.

The left panel of Figure 1 presents two survival functions, one for participants who expressed an interest in work and one for participants who expressed no interest in work. In the context of the present study, the survival functions show the probability that a participant does not obtain a job by a given point in time. Note that the survival functions approach zero as participants obtain jobs, indicating that the probability that a participant does not obtain a job decreases over time. The higher curve for those not interested in work indicates that these participants took longer to obtain a job. A log-rank test rejects the null hypothesis of equality of the two curves (χ2[1, N=160]=8.76, p=.003). A value of 0.5 on the ordinate corresponds to the point where half of the participants obtained jobs. Figure 1 suggests that the median survival time for half of the participants interested in work was about 300 days, whereas the curve for those not interested in work is still above 0.6 even after 500 days. The actual median survival times cannot be estimated because more than 50% of the observations in each group are right censored (Lee, 1992), with the longest survival times being censored values (i.e., survival time is equal to time-in-study for persons who did not work at all).

The right panel of Figure 1 presents the log of the negative log of the estimated survival function separately for the interest and no-interest groups. This type of plot is useful for assessing whether the proportional hazards assumption made in the regression model discussed below is appropriate (for the interest variable); if it is, then the curves should be approximately parallel. The right panel of Figure 1 shows that the curves appear to be parallel, so the proportional hazards assumption seems appropriate. We also check this assumption for the interest and other predictor variables by including interaction terms with time in the model.

To examine the effects of expressed interest in work and other variables on time to first job, a semiparametric proportional hazards model (Cox & Oakes, 1984) was used, which makes no assumptions about the distribution of the event times. This approach allows us to examine predictors of time to first job, while controlling for other variables, such as background and demographic characteristics. The basic approach is to model the log of the hazard rate (taking into account censored values) as a function of predictor variables. For discrete-time formulations, the hazard rate is the probability of an event occurring (e.g., obtaining a job) within a time interval, given that the event has not yet occurred. In the present analyses, we use a continuous time formulation, which Allison (1984) and Petersen (1995) note is most commonly used; the interpretation of the hazard rate is similar in this case, except that it refers to a density rather than to a probability.

Twenty variables, including initial interest in work and intervention condition, were entered as predictors in the model. From the results for this full model, we considered a reduced model that dropped nine predictors with small parameter-to-standard-error ratios. The reduced model included five demographic variables (gender, age, ethnicity, education, and residential status) to statistically control for their effects on employment, and three clinical variables (diagnosis, medication, and substance abuse), which past research has found to be predictive of consumer employment. Work variables included in the analysis were stated interest in paid work, receipt of vocational services, and years on longest job held before study entry. A likelihood ratio test of the effect of dropping the nine predictors is obtained by subtracting the −2 log likelihoods of the reduced model from that of the full model, which gives χ2(9, N=160)=0.807, p=.9997; therefore, the reduced model is not rejected.

Table 3 shows the parameter estimates for the reduced model. The demographic variables had no apparent effect on the hazard rate of obtaining a job. Time on longest prior job and whether a participant was on atypical medication also do not have significant effects. Participants with schizophrenia or a history of substance abuse did take longer to obtain a job, but these effects are marginal. In contrast, expressed interest in work and receipt of vocational services both clearly had significant effects; large positive coefficients for these two variables indicate that those who received vocational services obtained a job sooner, as did those who had expressed initial work interest.

TABLE 3.

Estimates from Semiparametric Proportional Hazards Model of Time to First Job on Predictors for Reduced Model (N=160)

| Variable | Estimate | SE | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male (dummy) | 0.178 | 0.258 | .4905 |

| Ethnic minority (dummy) | 0.408 | 0.347 | .2397 |

| Age (years) | 0.012 | 0.015 | .4296 |

| At least high school (dummy) | 0.462 | 0.322 | .1509 |

| Living independently (dummy) | 0.121 | 0.295 | .6805 |

| Length of time on longest job (years) | −0.052 | 0.033 | .1216 |

| Diagnosis of schizophrenia (dummy) | −0.450 | 0.263 | .0873 |

| Atypical anti-psychotic (dummy) | 0.258 | 0.258 | .3188 |

| History of substance abuse (dummy) | −0.440 | 0.256 | .0853 |

| Interest in paid work (dummy) | 1.060 | 0.355 | .0028 |

| Received vocational services (dummy) | 2.731 | 0.734 | .0002 |

The proportional hazards model assumes that hazard rates are proportional, and Figure 1 shows that this assumption appears to be valid for the interest variable. To see if this assumption is reasonable for the other variables included in the reduced model, we fit a model that included interaction terms of time (days to first job) with the 11 variables; this allows the log of the negative log survival functions to be non-parallel. Subtracting the −2 log likelihoods of the model with interaction terms from the model without interaction terms gives χ2(11, N=160)=10.116, p=.3411; an absence of significant interactions suggests that the assumption of proportional hazards is reasonable.

Relation of Work Interest to Duration of Work

As can be seen in Table 2, participants not initially interested in work actually worked longer than those who had expressed interest in work, regardless of whether duration of work is measured as total days of work, total hours of work, days per job, or days on longest job. Although persons who expressed no interest in work started work later than those expressing interest, the two groups worked the same percentage of time while in the project (35% vs. 35%). Participants interested and not interested in work also earned equivalent wages (M=$6.26 vs. $5.73 per hour) and worked equivalent hours per week (M=18.7 vs. 18.1).

Average total days of work was about 6 months, with time on a single job averaging a little more than 4 months. Interest and no-interest groups were evenly split between those who held single versus multiple jobs, with an average of two jobs per person (M=1.97; range=1–9). Although fewer ethnic minority participants had expressed an initial interest in work, they were more likely than Caucasian participants to actually take a job (51.4% vs. 42.7%) and eventually worked a comparable length of time while in the study (200.46 vs. 199.88 days). There were no statistically significant differences between PACT and Clubhouse on any work duration variable.

DISCUSSION

The present study’s intent-to-treat job placement rate of 29% for all participants not interested in work (that is, for those participants who typically would not enroll in an employment program) surpasses the estimated 7% to 15% work rates for the population of consumers with serious mental illness (Anthony & Blanch, 1987; Noble, 1998). Moreover, the competitive job placement rate of 48% for persons with no initial work interest who engaged in at least one hour of vocational service approximates the average 58% and 34% annual competitive job rates for experimental supported employment programs serving only work-interest consumers that have been reported in research reviews (Bond et al., 1997; Crowther, Marshall, Bond, & Huxley, 2001). This 48% employment rate for no-work-interest consumers also compares favorably with net increases of 11% to 57% in job placements over comparable periods of time attained by Individual Placement and Support (IPS) teams replacing day treatment programs. These small sample studies in New Hampshire (Drake, Becker, Biesanz, et al., 1994; Drake, Becker, et al., 1996) and Rhode Island (Becker et al., 2001) screened not only for work interest, but also for any impairments that might prevent work. Since these studies, like the present research, found that from one fourth to one third of all persons with serious mental illness are reluctant to enter employment programs, the present findings question the value of statewide initiatives that advocate for the sole provision of competitive employment services by such specialized programs. More important, cross-study comparisons suggest that rate of job placement may not be the best measure for informing policy decisions. Participants in the present study who did not have an initial interest in work were employed a comparable number of total hours over an average 12-month period (M=739.3) as participants in either an IPS program (M=777.4 hours) or a group skills training program (M=509.7 hours) over a longer 18-month study period (Drake, McHugo, et al., 1996). Once vocational supports are in place, persons not initially interested in work who decide to try work can stay employed as long or longer than highly motivated consumers.

The success of vocationally integrated PACT and certified clubhouse programs with persons not initially interested in work leads to a question of practical importance: Does the allocation of vocational service dollars to persons uninterested in work compromise the outcomes of other consumers in the same program who are committed to obtaining employment? When the results of the present study are compared with the outcomes of comparable research samples over 18-month periods, the overall 68% employment rate for persons interested in work who received PACT and Clubhouse vocational services approximates the exemplary 61% and 78% published rates for the model of IPS (Drake, McHugo, et al., 1996; Drake et al. 1999). Apparently, providing less motivated consumers with the same or more vocational services does not reduce employment opportunities for those already interested in finding competitive work.

CONCLUSIONS

Study findings suggest that about a third of all mental health consumers lack the initiative or interest to enroll in an employment program, and stated disinterest reflects a genuine hesitancy to seek competitive work. It is reasonable to use interest in work, expressed either verbally or through attendance at mandatory induction sessions, as a screening device to concentrate program resources on the most highly motivated and promising individuals. However, the findings also show that receptivity to work can be improved through the receipt of vocational services, and, therefore, reported (dis)interest is not a justifiable inclusion (or exclusion) criterion. Although consumers lacking an initial interest in work may require more services and take longer to become employed, many are as capable of job success as persons initially interested in work if they are encouraged in their efforts.

It is crucial that policy makers consider the findings of the present study when allocating public funds for vocational services. Most existing service systems have centralized coordination of separate mental health and vocational programs by umbrella agencies (e.g., mental health centers). Auspice agency oversight is intended to ensure that consumers get the services they need. However, it is questionable whether the limited extent of services integration achieved through intra-program collaboration can effectively serve all persons with serious mental illness. As Leona Bachrach (1996) has pointed out, program gatekeeping is most problematic when it is subtle (i.e., when admission is restricted not on the basis of some obvious personal characteristic of the consumer, but on the basis of a lack of consumer receptivity to the program’s special offerings). Such a subtle bias is clearly the case when vocational programs base admission on consumers’ a priori willingness to go to work. Persons who lack the confidence to enroll in an employment program will not be given opportunities to envision themselves working. Considering the emphasis now being placed on rapid job placement and the widespread belief that work itself engenders work motivation, it is contradictory and of questionable ethics to limit the availability of vocational services. Such a restriction in services is akin to stopping outreach to homeless individuals or to persons with substance abuse whenever these individuals do not immediately see the benefits of accepting housing or treatment. A lack of receptivity to services does not alter a person’s need. When service networks stratify the population of adults with serious mental illness into those who can recover and move on with their lives (e.g., those with work interest who are admitted to vocational programs) versus those that must be stabilized and maintained (e.g., those with no work interest who receive no vocational supports), then these service networks become “just as sturdy institutions as the old state hospitals” (Harding, 1996). The findings of the present study underscore the viability of providing employment supports in tandem with other community support services within all mental health programs.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to give credit to the project’s Advisory Council which oversaw all aspects of the research project: Gerald Kokernak, Elaine Hill, Kenneth Hetzler, Deborah Ekstrom, Mary Query, Dorothy LaPointe, Grace LaPearl, Ann Healy, Paul DeNubila, Patricia Colonna, Ellen McGrail, Kevin Bradley, Colleen McKay, Allison Negron, and Jeffrey Stovall. Special thanks are extended to Marylou Sudders, Commissioner of Mental Health for the State of Massachusetts, for her continual support and recognition that made the project possible, and to the University of Massachusetts Medical School, Department of Psychiatry, which provided the project with office space. Thanks is also extended to the members and research staff of Fountain House in New York City who entered and checked the data, especially Andrew Schonebaum, M.A., Research Unit Leader. Special thanks to Charles Rodican, M.S.W., Research Administrator of Fountain House, who oversaw all aspects of the research project and provided insightful critiques of the manuscript.

Footnotes

This publication was made possible by cooperative agreement number SM 51831 to Fountain House, Inc., from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) Center for Mental Health Services (CMHS) as part of the Employment Intervention Demonstration Program (EIDP). Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the DHHS, SAMHSA, CMHS, or other EIDP collaborating partners. Funding for data analysis was provided by grants to Fountain House, Inc., from the van Ameringen Foundation and from Llewellyn and Nicholas Nicholas.

Contributor Information

Cathaleene Macias, Director of Research at Fountain House, Inc., New York, NY.

Lawrence T. DeCarlo, Assistant Professor at Teachers College, Columbia University, New York, NY

Qi Wang, Senior Researcher at Fountain House, Inc., New York, NY

Jana Frey, Director of the Program of Assertive Community Treatment at Mendota Mental Health Institute, Madison, WI

Paul Barreira, Chief of Community Clinical Services, McLean Hospital, Harvard Medical School

References

- Ajzen I. The directive influence of attitudes on behavior. In: Gollwitzer PM, Bargh JA, editors. The psychology of action. New York: The Guilford Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Allison PD. Event history analysis: Regression for longitudinal event data. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson SB. We are not alone: Fountain House and the development of clubhouse culture. New York: Fountain House; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Anthony W, Blanch A. Supported employment for persons with psychiatric disabilities: A historical and conceptual perspective. Psychosocial Rehabilitation Journal. 1987;11(2):5–24. [Google Scholar]

- Bachrach LL. Psychosocial rehabilitation and psychiatry: What are the boundaries? Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. 1996;41:28–35. doi: 10.1177/070674379604100108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beard JH. The rehabilitation services of Fountain House. In: Stein L, Test MA, editors. Alternatives to mental hospital treatment. New York: Plenum Press; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Beard JH, Propst RN, Malamud TJ. The Fountain House model of psychiatric rehabilitation. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal. 1982;5:47–53. [Google Scholar]

- Bebout RR, Becker DR, Drake RE. A research induction group for clients entering a mental health research project: A replication study. Community Mental Health Journal. 1998;34(3):289–295. doi: 10.1023/a:1018769825030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker D, Bond GR, McCarthy D, Thompson D, Xie H, McHugo GJ, Drake RE. Converting day treatment centers to supported employment programs in Rhode Island. Psychiatric Services. 2001;52(3):351–357. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.52.3.351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker D, Drake R, Farabaugh A, Bond G. Job preferences of clients with severe psychiatric disorders participating in supported employment programs. Psychiatric Services. 1996;47(11):1223–1226. doi: 10.1176/ps.47.11.1223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell M, Milstein R, Lysaker P. Pay and participation in work activity: Clinical benefits for clients with schizophrenia. Psychosocial Rehabilitation Journal. 1993;17(2):173–176. [Google Scholar]

- Bickman L. A continuum of care: More is not always better. American Psychologist. 1996;51(7):689–701. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.51.7.689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black BJ. Work and mental illness: Transitions to employment. Baltimore, MD: The Johns Hopkins University Press; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Bond GR, Drake RE, Becker DR, Mueser KT. Effectiveness of psychiatric rehabilitation approaches for employment of people with severe mental illness. Journal of Disability Policy Studies. 1999;10(1):18–52. [Google Scholar]

- Bond GR, Drake RE, Mueser KT, Becker DR. An update on supported employment for people with severe mental illness. Psychiatric Services. 1997;48(3):335–346. doi: 10.1176/ps.48.3.335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bond GR, Picone J, Mauer B, Fishbein S, Stout R. The Quality of Supported Employment Implementation Scale. Journal of Vocational Rehabilitation. 2000;14:201–212. [Google Scholar]

- Brekke JS, Ansel M, Long J, Slade E, Weinstein M. Intensity and continuity of services and functional outcomes in the rehabilitation of persons with schizophrenia. Psychiatric Services. 1999;50(2):248–256. doi: 10.1176/ps.50.2.248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bybee D, Mowbray CT, McCrohan NM. Towards zero exclusion in vocational services for persons with psychiatric disabilities: Prediction of service receipt in a hybrid vocational/case management service program. Psychosocial Rehabilitation Journal. 1996;19(4):15–27. [Google Scholar]

- Chandler D, Levin S, Barry P. The menu approach to employment services: Philosophy and five-year outcomes. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal. 1999;23(1):24–33. [Google Scholar]

- Cook JA, Razzano L. Natural vocational supports for persons with severe mental illness: Thresholds supported competitive employment program. New Directions for Mental Health Services. 1992;56:23–41. doi: 10.1002/yd.23319925604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook JA, Razzano L. Vocational rehabilitation for persons with schizophrenia: Recent research and implications for practice. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2000;26(1):87–103. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a033448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox DR, Oakes D. Analysis of survival data. London: Champman and Hall; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Crowther RE, Marshall M, Bond GR, Huxley P. Helping people with severe mental illness to obtain work: Systematic review. British Medical Journal. 2001;322:204–208. doi: 10.1136/bmj.322.7280.204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danley KS, Anthony WA. The Choose-Get-Keep Model: Serving severely disabled psychiatrically disabled people. American Rehabilitation. 1987;13(4):27–29. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Labor. Job Training Program Act, Disability Grant Program Funded Under Title III, Section 323, and Title IV, Part D, Section 452. Federal Register. 1998 Mar 30;63(60) [Google Scholar]

- Diksa E, Rogers S. Employer concerns about hiring persons with a psychiatric disability: Results of the employer attitude questionnaire. Rehabilitation Counseling Bulletin. 1996;40(1):31–44. [Google Scholar]

- Dooley D, Catalano R, Wilson G. Depression and unemployment: Panel findings from the Epidemiologic Catchment Area Study. American Journal of Community Psychology. 1994;22(6):745–761. doi: 10.1007/BF02521557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drake RE. A brief history of the Individual Placement and Support Model. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal. 1998;22(1):3–7. [Google Scholar]

- Drake RE, Becker DR, Anthony WA. The use of a research induction group in mental health services research. Hospital and Community Psychiatry. 1994;45:487–489. doi: 10.1176/ps.45.5.487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drake RE, Becker DR, Biesanz JC, Torrey WC, McHugo GJ, Wyzik PF. Rehabilitative day treatment vs. supported employment: I. Vocational outcomes. Community Mental Health Journal. 1994;30(5):519–532. doi: 10.1007/BF02189068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drake RE, Becker DR, Biesanz JC, Wyzik PF, Torrey WC. Day treatment versus supported employment for persons with severe mental illness: A replication study. Psychiatric Services. 1996;47(10):1125–1127. doi: 10.1176/ps.47.10.1125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drake RE, McHugo GJ, Bebout RR, Becker DR, Harris M, Bond GR, Qimby E. A randomized clinical trial of supported employment for inner-city patients with severe mental disorders. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1999;56:627–633. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.56.7.627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drake RE, McHugo GJ, Becker DR, Clark RE, Anthony WA. The New Hampshire Study of supported employment for people with severe mental illness. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1996;64(2):391–399. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.64.2.391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frey JL. Long term support: The critical element to sustaining competitive employment: Where do we begin? Psychosocial Rehabilitation Journal. 1994;17(3):127–133. [Google Scholar]

- Gates LB, Akabas SH, Oran-Sabia V. Relationship accommodations involving the work group: Improving work programs for persons with mental illness. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal. 1998;21(3):264–272. [Google Scholar]

- Gervey R, Parrish A, Bond GR. Survey of exemplary supported employment programs for persons with psychiatric disabilities. Journal of Vocational Rehabilitation. 1995;5:115–125. [Google Scholar]

- Goldman H, Rosenberg J, Manderscheid RW. Defining the target population for vocational rehabilitation. In: Ciardiello JA, Bell MD, editors. Vocational rehabilitation of persons with prolonged psychiatric disorders. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Gollwitzer PM. Implementation intentions: Strong effects of simple plans. American Psychologist. 1999;54(7):493–503. [Google Scholar]

- Harding CM. Some things we’ve learned about vocational rehabilitation of the seriously and persistently mentally ill. Paper presented at the Boston University Research Colloquium; Brookline, MA. 1996. Apr, [Google Scholar]

- Harding CM, Strauss JS, Hafez H, Lieberman PB. Work and mental illness: Toward an integration of the rehabilitation process. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 1987;175(6):317–327. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs HE, Collier R, Wissusik D. The job-finding module: Training skills for seeking competitive employment. New Directions in Mental Health Services. 1992;53:105–115. doi: 10.1002/yd.23319925312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kay SR, Fiszbein A, Opler LA. The positive and negative syndrome scale (PANSS) for schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 1987;13:261–276. doi: 10.1093/schbul/13.2.261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein JP, Moeschberger ML. Survival analysis: Techniques for censored and truncated data. New York: Springer-Verlag; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Lee ET. Statistical methods for survival data analysis. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Lehman AF, Kernan E, Postrado L. Toolkit for evaluating quality of life for persons with severe mental illness. Cambridge, MA: HSRI; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Macias C, Barreira P, Alden M, Boyd J. Benchmarks of mental health organizational performance: A practical approach to setting goals for psychiatric rehabilitation. Psychiatric Services. 2001;52(2):207–213. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.52.2.207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macias C, Jackson R, Schroeder C, Wang Q. What is a clubhouse? Report on the ICCD 1996 Survey of USA Clubhouses. Community Mental Health Journal. 1999;35(2):181–190. doi: 10.1023/a:1018776815886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macias C, Propst R, Rodican C, Boyd J. Strategic planning for ICCD clubhouse implementation: Development of the Clubhouse Research and Evaluation Screening Survey (CRESS) Mental Health Services Research. doi: 10.1023/a:1011523615374. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macias C, Rodican C. Coping with recurrent loss in mental illness: Unique aspects of clubhouse communities. Journal of Personal and Interpersonal Loss. 1997;2:205–221. [Google Scholar]

- McFarlane WR, Stastny P, Deakins SA, Dushay R. Employment outcomes in Family-aided Assertive Community Treatment (FACT). Paper presented at the American Psychiatric Association Institute on Psychiatric Services; Boston, MA. 1995. Oct, [Google Scholar]

- Mowbray CT, Rusilowski-Clover G, Arnold J, Allen C, Harris S, McCrohan N, Greenfield A. Project WINS: Integrating vocational services on mental health case management teams. Community Mental Health Journal. 1994;30(4):347–362. doi: 10.1007/BF02207488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noble JH., Jr Policy reform dilemmas in promoting employment of persons with severe mental illnesses. Psychiatric Services. 1998;49(6):775–781. doi: 10.1176/ps.49.6.775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noble JH, Jr, Honberg RS, Hall LL, Flynn LM. A legacy of failure: The inability of the federal-state vocational rehabilitation system to serve people with severe mental illness. Arlington, VA: National Alliance for the Mentally Ill; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Okapaku SO, Anderson KH, Sibulkin AE, Butler JS, Bickman L. The effectiveness of a multidisciplinary case management intervention on the employment of SSDI applicants and beneficiaries. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal. 1997;20(3):34–41. [Google Scholar]

- Petersen T. Analysis of event histories. In: Arminger G, Clogg CC, Sobel ME, editors. Handbook of statistical modeling for the social and behavioral sciences. New York: Plenum Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Propst R. The standards for clubhouse programs: Why and how they were developed. Psychosocial Rehabilitation Journal. 1982;16(2):25–30. [Google Scholar]

- Rimmerman A, Botuck S, Levy JM. Job placement for individuals with psychiatric disabilities in supported employment. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal. 1995;19(2):37–44. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers J. Work is key to recovery. Psychosocial Rehabilitation Journal. 1995;18(4):5–10. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg M. Conceiving the self. New York: Basic Books; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Russert MG, Frey JL. The PACT vocational model: A step into the future. Psychosocial Rehabilitation Journal. 1991;14(4):7–18. [Google Scholar]

- Singer JD, Willett JB. Modeling the days of our lives: Using survival analysis when designing and analyzing longitudinal studies of duration and the timing of events. Psychological Bulletin. 1991;110:268–290. [Google Scholar]

- Stein L, Test MA. An alternative to mental hospital treatment: I. Conceptual model, treatment program and clinical evaluation. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1980;37:392–397. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1980.01780170034003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strauss JS, Harding CM, Silverman M. Work as treatment for psychiatric disorder: A puzzle in pieces. In: Ciardello JA, Bell MD, editors. Vocational rehabilitation for persons with prolonged mental illness. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Test MA, Knoedler W, Allness DJ, Burke SS, Kameshima S, Rounds L. Comprehensive community care of persons with schizophrenia through the Programme of Assertive Community Treatment (PACT) In: Brenner HD, Boker W, Genner R, editors. Toward a comprehensive therapy for schizophrenia. Seattle, WA: Hogrefe & Huber; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Test MA, Stein LI. An alternative to mental hospital treatment: III. Social cost. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1980;37:409–412. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1980.01780170051005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trach JS. Supported employment program characteristics. In: Rusch R, editor. Supported employment: Models, methods and issues. Sycamore, IL: Sycamore Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Trumbetta S, McHugo GJ, Drake RE. EIDP Study Interview Reliability Report. Concord, NH: Dartmouth University; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Workforce Investment Act of 1998. PL 105–220, Aug. 7, 1998.