Abstract

In comparison to men, women exhibit enhanced responsiveness to the stimulating and addictive properties of cocaine. A growing body of evidence implicates the steroid hormone estradiol in mediating this sex difference, yet the mechanisms underlying estradiol enhancement of behavioral responses to cocaine in females are not known. Recently, we have found that estrogen receptor alpha (ERα) functionally couples with the metabotropic glutamate receptor 5 (mGluR5) to mediate the effects of estradiol on both cellular activation as well as dendritic spine plasticity in brain regions involved in cocaine-induced behavioral sensitization. Thus, we sought to determine whether mGluR5 activation is required for the facilitative effects of estradiol on locomotor responses to cocaine. To test this hypothesis, ovariectomized (OVX) female rats were tested for locomotor activity on the first and fifth days of daily systemic injections of cocaine. For the two days prior to each locomotor test, animals were injected with the mGluR5 antagonist MPEP (or vehicle) and estradiol (or oil). MPEP treatment blocked the facilitative effects of estradiol on cocaine-induced locomotor sensitization, without affecting acute responses to cocaine or the inhibitory actions of estradiol on weight gain. Considered together, these data indicate that mGluR5 activation is critical for the actions of estradiol on cocaine-induced behavioral sensitization.

Keywords: nucleus accumbens, estrogen, drug addiction, behavioral sensitization

Abuse of psychostimulants such as cocaine differs between men and women. Women begin using psychostimulants at an earlier age than men, escalate their use more quickly, and report greater subjective effects of these drugs [1]. Notably, responses to cocaine in women vary across the menstrual cycle with elevated responsiveness during the follicular phase [2], highlighting the contribution of estradiol to this differential response to cocaine. Indeed, studies in rodents have demonstrated that sex differences in the behavioral response to cocaine are eliminated following ovariectomy, and are restored following treatment with estradiol [3,4]. Despite such observations, little is known regarding the underlying neural mechanisms that mediate the facilitative effects of estradiol on cocaine-induced behaviors.

There is a growing body of evidence implicating metabotropic glutamate receptors (mGluRs) as an underlying mechanism for many of the neuroanatomical and behavioral effects of estradiol [5]. Recently, we found that estrogen receptor alpha (ERα) is functionally coupled to mGluR5 in striatal medium spiny neurons (MSNs) [6], an interaction that appears to be critical for plasticity within brain areas that regulate behavioral sensitization to cocaine. Similar to several recent studies examining the effects of cocaine [7,8], estradiol decreases dendritic spine density of MSNs in the core subdivision of the nucleus accumbens 24-48 hours after hormone administration [9]. Furthermore, pretreatment with the mGluR5 antagonist MPEP blocks this effect of estradiol [10]. Given that mGluR5 signaling has previously been implicated in the locomotor responses to cocaine [11,12], we hypothesized that in females ERα/mGluR5 signaling is required for estradiol facilitation of cocaine-induced locomotor sensitization.

Ovariectomized Sprague-Dawley rats were purchased from Harlan Laboratories (Madison, WI, USA) at 175-199 g, and pair housed upon arrival in polycarbonate cages with wire mesh tops. Females were maintained on a 12:12 hr light:dark cycle (lights on at 6 am), with all behavior testing occurring between the hours of 9 am and 2 pm. Food and water were available ad libitum. Animal procedures were carried out in accordance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (8th Ed.) and approved by the University of Minnesota Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

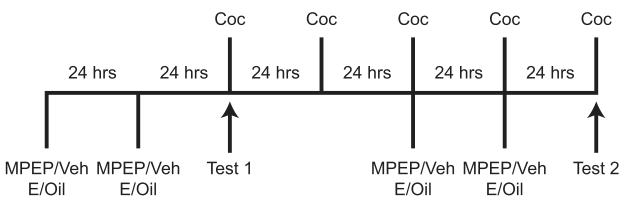

Throughout the experiment, females were injected s.c. with 2 μg of estradiol (17β-estradiol; Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) in 0.1 ml cottonseed oil (or cottonseed oil alone), on a two days on, two days off schedule (Figure 1). Females were also injected i.p. with 1 mg/kg/ml MPEP (2-methyl-6-(phenylethynyl)pyridine hydrochloride; Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA) in saline (or saline vehicle alone) 30 min prior to each hormone injection. We found previously that this dose of MPEP blocks estradiol-induced changes in dendritic spines within the nucleus accumbens core when measured 24 hrs later, but has no effect on spine density in the absence of estradiol treatment [10]. Beginning on the third day of the experiment (the day immediately following the second day of hormone injections), females were injected i.p. for five consecutive days with 15 mg/kg/ml of cocaine (cocaine hydrochloride; Sigma) in saline. This pattern of cocaine injections was chosen because it induces modest (if any) sensitization in untreated OVX female rats [1,4], thereby allowing us to more clearly identify the facilitative effect of estradiol on sensitization as well as any potential blockade of that effect following MPEP treatment.

Figure 1.

Timeline of experimental manipulations. OVX female rats were injected with MPEP or vehicle (Veh), followed by estradiol (E) or oil, on days 1, 2, 5, and 6 (n = 12-13 per group). Cocaine (Coc) was injected on days 3-7. Locomotor activity was assessed on the first and fifth Coc injection days.

Locomotor activity was assessed in clear, polycarbonate open field chambers (47.5 × 25.5 × 20.5 cm) containing corncob bedding. Females were initially placed into a chamber for 30 min (Habituation session), injected with cocaine, and then immediately returned to that chamber for 60 min (Test session). Each chamber was situated within a sensing frame (Kinder Scientific, Poway, CA, USA) that generated an X-Y grid of photobeams within the chamber. Data from the sensing frames were transmitted to a computer running Motor Monitor software (Kinder Scientific). This software further discriminated beam breaks into ambulations and fine movements. Ambulations were defined as a change of the animal’s entire body position on the X-Y grid. Fine movements were defined as all beam breaks that did not meet the criterion for an ambulation. Fine movements therefore comprised a range of behaviors, including grooming and sniffing. The number of rears (elevation of the animal onto its hind paws with fore paws placed upon the wall of the chamber) was also quantified, by a researcher blind to the experimental condition of the animal. At the conclusion of the Test session, females were returned to their home cages.

All data were analyzed using SPSS for Macintosh, version 20.0 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY, USA). Data were first examined to determine if the assumptions of parametric statistical tests were met. For all statistical tests, results were considered to be significant if p < .05. Body weight was subjected to a mixed-design factorial ANOVA, with time (initial weight, weight at first cocaine test, and weight at fifth cocaine test) as a repeated factor, and drug (MPEP or vehicle) and hormone (estradiol or oil) as independent factors. Significant time x hormone interactions were further examined for the effect of time within each hormone treatment group using paired-samples t-tests (error term derived from interaction analysis), with Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons. The number of ambulations, fine movements, and rears during the first and fifth Habituation and Test sessions were also examined via factorial ANOVAs, and significant time x drug x hormone interactions were further examined for the effect of time within each treatment group using paired-samples t-tests (error term derived from interaction analysis).

MPEP injections did not significantly affect locomotor responses during Habituation sessions. Females performed fewer ambulations (F(1,45) = 90.61, p = .000), fine movements (F(1,46) = 60.35, p = .000), and rears (F(1,43) = 45.63, p = .000) in the fifth vs. the first session (data not shown). However, there were no significant effects of drug, hormone, or drug x hormone interactions.

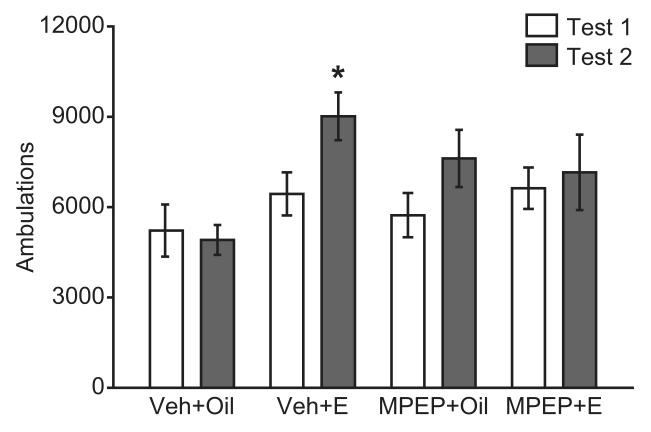

MPEP treatment blocked the estradiol facilitation of sensitized ambulatory activity following repeated cocaine injections. The effects of estradiol treatment and test session on ambulatory activity differed across drug treatment groups, as evidenced by a significant time x drug x hormone treatment interaction (F(1,43) = 4.49, p = .040) (Figure 2). Specifically, females treated with estradiol + vehicle had significantly higher ambulations in the fifth vs. first Test sessions (t(11) = −2.61, p = .024), an effect that was not observed in any other treatment group. There were no significant effects of drug, hormone, or significant drug x hormone interaction on the initial ambulatory responses to cocaine.

Figure 2.

Estradiol enhancement of cocaine-induced ambulations is dependent on mGluR5. In estradiol (E) treated females, ambulations (mean ± SEM) were higher in response to the fifth cocaine (Coc) vs. first Coc injection (Test 2 vs. Test 1, *p < .05 (paired-samples t-test)). This hormone effect was not observed when MPEP was administered 30 minutes prior to estradiol. In addition, MPEP alone did not affect Coc-induced ambulations.

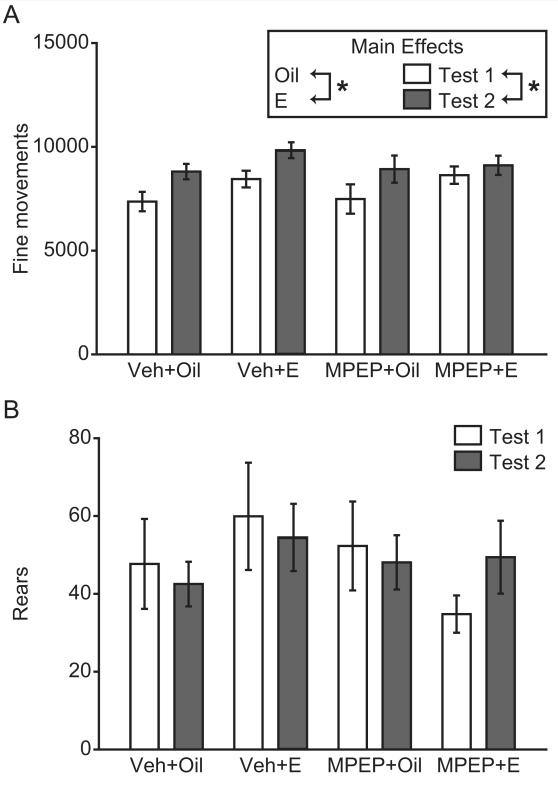

Treatment with MPEP did not significantly affect measures of non-ambulatory locomotor activity. During the Test sessions, females exhibited more fine movements during the fifth vs. the first session (F(1,44) = 12.08, p = .001) and more fine movements in response to estradiol compared to oil treatment (F(1,44) = 5.03, p = .030) (Figure 3A). These effects did not significantly differ as a function of MPEP treatment. There were also no significant effects of time, drug, or hormone treatment on rearing during the Test sessions, or significant interaction of these factors (Figure 3B).

Figure 3.

Increase in fine motor movements following estradiol treatment and across test day. (A) Females exhibited more fine movements following the fifth cocaine (Coc) vs. the first Coc injection (Test 2 vs. Test 1), and more fine movements when injected with estradiol (E) vs. oil. (B) There were no differences within/across groups on rearing. *p < .05 (ANOVA main effect).

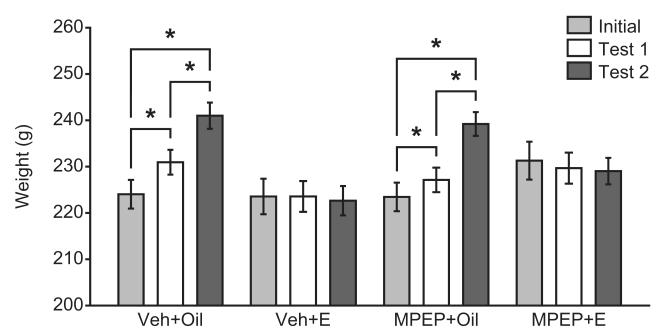

Treatment with estradiol significantly attenuated weight increases in OVX females. The effect of time on weight gain differed depending on hormone treatment group (F(2,90) = 107.03, p = .000), but did not significantly differ across drug treatment groups or across both drug and hormone treatments. Weight increased significantly from the start of the experiment to the first session (t(24) = −6.15, p = .000), and from the first to the fifth session (t(24) = −12.65, p = .000), in oil-treated females irrespective of drug condition (Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons). This pattern of weight increase with time was not observed in estradiol-treated females.

Our findings demonstrate that estradiol facilitation of cocaine-induced locomotor sensitization depends critically on activation of the metabotropic glutamate receptor subtype mGluR5. This effect was specific to ambulatory responses, since injections of the mGluR5 antagonist MPEP did not block the effects of estradiol treatment on other motor responses or on weight gain. In light of previous work implicating mGluR5 in mediating estradiol-dependent neural plasticity within the nucleus accumbens core (NAcC), our data identify a novel mechanism whereby estradiol can potentiate cocaine-induced locomotor sensitization in females, as well as a potential therapeutic target for treating psychostimulant addiction in women.

The effects of MPEP on estradiol facilitation of locomotor responses were specific to sensitized, rather than acute, responses to cocaine. Furthermore, MPEP treatment alone did not significantly alter ambulatory responses. This is likely due to the timing and dose of our drug injections. We chose to administer 1 mg/kg MPEP only on the two days before each locomotor test, given previous studies demonstrating that higher doses inhibit the acute cocaine-induced locomotor responses when administered just prior to testing [11,12]. This highlights one of the advantages of the present work. Using a lower dose and shifting the timing of injections allowed the effects of MPEP to be more directly attributed to blocking the downstream effects of estradiol, a critical point given the focus of the present work on elucidating the mechanisms underlying estradiol effects on locomotor sensitization. But consequently, the role of mGluR5 signaling independent of estradiol remains to be more clearly established within our model (e.g., the role of mGluR5 agonism on structural plasticity and locomotor sensitization in females).

In addition to the locomotor-facilitating effects of estradiol, we also observed an inhibition of weight gain in estradiol-treated females that is consistent with previous work [13]. Therefore, one could posit that the observed effects of MPEP represent indirect actions on estradiol-dependent physiological responses (e.g., food intake and/or metabolism). This seems unlikely for two reasons. First, weight gain was inhibited in estradiol-treated females that received either MPEP or vehicle. Second, the degree of locomotor sensitization did not correlate with changes in weight, regardless of hormone or drug treatment condition (data not shown). These results suggest that MPEP acted to specifically inhibit the locomotor-enhancing effects of estradiol, without broadly disrupting physiological processes related to locomotion.

Our findings implicate mGluR5 activation in the signaling pathway whereby estradiol ultimately facilitates cocaine-induced locomotion. This may occur via an estrogen receptor alpha (ERα)-dependent mechanism. In OVX female mice, activation of ERα through systemic administration of PPT increases ambulations and stereotypy scores compared to untreated females, an effect that is not mimicked by administration of DPN, an estrogen receptor beta agonist [14]. Furthermore, treatment with PPT, but not DPN, in OVX females increased responding on the inactive lever (an indication of general locomotor activation) during reinstatement of cocaine self administration [15].

Our group has previously shown that in the female striatum, ERα can directly transactivate mGluR5 [6]. The present data are consistent with this model. Interestingly, activation of group I mGluR signaling by estradiol has both immediate and long-term consequences within the nervous system. Insight can be drawn from studies examining the neural regulation of female sexual receptivity. Within this model, stimulation of membrane estrogen receptors in the hypothalamus is required to elicit lordosis behavior days later [16]. Initial actions of ERα/mGluR1a signaling result in the rapid (within 30 min) activity-induced internalization of μ-opioid receptors in the medial preoptic nucleus [17], followed by a slower (within 4 hrs) but lasting increase in dendritic spine density in the arcuate nucleus [18]. This parallels what is seen within the striatum. Specifically, stimulation of estrogen receptors [19] or group 1 mGluRs [20] rapidly induce striatal dopamine release, via disinhibition of local dopaminergic terminals [21]. These pathways appear integrated, as estradiol facilitation of dopamine release via inhibition of GABAergic signaling is dependent on mGluR5 [22]. Hours later, this same signaling pathway results in the reduction in dendritic spine density within the NAcC [9,10]. Given that estradiol can potentiate cocaine-induced locomotor sensitization when administered repeatedly beginning 30 min [3] or several days prior to the first cocaine injection [4,23,24], stimulation of the ERα/mGluR5 signaling pathway likely results in an coordinated sequence of acute and longer-lasting effects within the NAcC, which may ultimately lead to the behavioral outcomes observed here.

A substantial body of evidence supports a role for the NAcC in the behavioral and neuroanatomical responses to cocaine. Lesions of the NAcC increase novelty- and cocaine-induced locomotor responses in male rats [25], whereas lesions of the nucleus accumbens shell have no effect. Structural plasticity within the NAcC as well as changes in excitability [26] may be critical for mediating the sensitizing effects of cocaine on locomotor activity. Initial studies suggested an increase in dendritic spine density within the NAcC following chronic cocaine [e.g., 27,28]. However, more recent studies using advanced staining techniques and 3-D imaging, thought to more accurately capture neuroanatomical structure [29], have observed a decrease in spine density within this brain region following cocaine administration [7,8], similar to the acute effects of estradiol. The cooperative properties of estradiol and cocaine regulating neuroplasticity within the NAcC may therefore provide the basis for females exhibiting heightened responsiveness to psychostimulants.

Considered in light of previous research, our data suggest that estradiol may act via an mGluR5-dependent mechanism to potentiate the neuroanatomical and locomotor-stimulating effects of cocaine. Despite strong commonalities between the development of behavioral sensitization and addiction susceptibility [30], the behavioral sensitization model cannot capture the full extent of psychostimulant use/abuse. Further research is required to determine whether the effects of estradiol on psychostimulant self-administration in females are also dependent on interactions between ERα and mGluR5.

Highlights.

mGluR5 blockade disrupted estradiol-enhancement of locomotor sensitization

There was no effect on non-ambulatory locomotor responses (e.g., rearing)

Physiological responses to estradiol were also not disrupted by mGluR5 blockade

Figure 4.

Estradiol attenuation of weight gain is unaffected by mGluR5 antagonism. In oil-treated OVX females, weight increased across the experimental time course, an effect that was not observed following estradiol (E) treatment. The inhibitory effects of E were not altered by MPEP treatment. *p < .05 (paired-samples t-tests with Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons).

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Sonal Nagpal for her assistance with data collection. This work was supported by NIH grants DA035008 to PGM and RLM, DA035008-S1 to PGM and LAM, and core funding NS062158.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- [1].Segarra AC, Agosto-Rivera JL, Febo M, Lugo-Escobar N, Menéndez-Delmestre R, Puig-Ramos A, et al. Estradiol: A key biological substrate mediating the response to cocaine in female rats. Horm Behav. 2010;58:33–43. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2009.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Evans SM, Haney M, Foltin RW. The effects of smoked cocaine during the follicular and luteal phases of the menstrual cycle in women. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2002;159:397. doi: 10.1007/s00213-001-0944-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Hu M, Becker JB. Effects of sex and estrogen on behavioral sensitization to cocaine in rats. J Neurosci. 2003;23:693–9. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-02-00693.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Sircar R, Kim D. Female gonadal hormones differentially modulate cocaine-induced behavioral sensitization in Fischer, Lewis, and Sprague-Dawley rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1999;289:54–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Meitzen J, Mermelstein PG. Estrogen receptors stimulate brain region specific metabotropic glutamate receptors to rapidly initiate signal transduction pathways. J Chem Neuroanat. 2011;42:236–41. doi: 10.1016/j.jchemneu.2011.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Grove-Strawser D, Boulware MI, Mermelstein PG. Membrane estrogen receptors activate the metabotropic glutamate receptors mGluR5 and mGluR3 to bidirectionally regulate CREB phosphorylation in female rat striatal neurons. Neuroscience. 2010;170:1045–55. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2010.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Dumitriu D, LaPlant Q, Grossman YS, Dias C, Janssen WG, Russo SJ, et al. Subregional, dendritic compartment, and spine subtype specificity in cocaine regulation of dendritic spines in the nucleus accumbens. J Neurosci. 2012;32:6957–66. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5718-11.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Waselus M, Flagel SB, Jedynak JP, Akil H, Robinson TE, Watson SJ., Jr. Long-term effects of cocaine experience on neuroplasticity in the nucleus accumbens core of addiction-prone rats. Neuroscience. 2013;248:571–84. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2013.06.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Staffend NA, Loftus CM, Meisel RL. Estradiol reduces dendritic spine density in the ventral striatum of female Syrian hamsters. Brain Struct Funct. 2011;215:187–94. doi: 10.1007/s00429-010-0284-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Peterson BM, Mermelstein PG, Meisel RL. Estradiol mediates dendritic spine plasticity in the nucleus accumbens core through activation of mGluR5. Brain Struct Funct. 2014 doi: 10.1007/s00429-014-0794-9. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].McGeehan AJ, Janak PH, Olive MF. Effect of the mGluR5 antagonist 6-methyl-2-(phenylethynyl)pyridine (MPEP) on the acute locomotor stimulant properties of cocaine, d-amphetamine, and the dopamine reuptake inhibitor GBR12909 in mice. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2004;174:266–73. doi: 10.1007/s00213-003-1733-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Herzig V, Schmidt WJ. Effects of MPEP on locomotion, sensitization and conditioned reward induced by cocaine or morphine. Neuropharmacology. 2004;47:973–84. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2004.07.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Wade GN. Gonadal hormones and behavioral regulation of body weight. Physiol Behav. 1972;8:523–34. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(72)90340-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Van Swearingen AED, Sanchez CL, Frisbee SM, Williams A, Walker QD, Korach KS, et al. Estradiol replacement enhances cocaine-stimulated locomotion in female C57BL/6 mice through estrogen receptor alpha. Neuropharmacology. 2013;72:236–49. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2013.04.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Larson EB, Carroll ME. Estrogen receptor β, but not α, mediates estrogen’s effect on cocaine-induced reinstatement of extinguished cocaine-seeking behavior in ovariectomized female rats. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2006;32:1334–45. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Kow L-M, Pfaff DW. The membrane actions of estrogens can potentiate their lordosis behavior-facilitating genomic actions. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:12354–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0404889101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Dewing P, Boulware MI, Sinchak K, Christensen A, Mermelstein PG, Micevych P. Membrane estrogen receptor-α interactions with metabotropic glutamate receptor 1a modulate female sexual receptivity in rats. J Neurosci. 2007;27:9294–300. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0592-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Christensen A, Dewing P, Micevych P. Membrane-initiated estradiol signaling induces spinogenesis required for female sexual receptivity. J Neurosci. 2011;31:17583–9. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3030-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Becker JB. Direct effect of 17β-estradiol on striatum: Sex differences in dopamine release. Synapse. 1990;5:157–64. doi: 10.1002/syn.890050211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Bruton RK, Ge J, Barnes NM. Group I mGlu receptor modulation of dopamine release in the rat striatum in vivo. Eur J Pharmacol. 1999;369:175–81. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(99)00072-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Schultz KN, Esenwein SA von, Hu M, Bennett AL, Kennedy RT, Musatov S, et al. Viral vector-mediated overexpression of estrogen receptor-α in striatum enhances the estradiol-induced motor activity in female rats and estradiol-modulated GABA release. J Neurosci. 2009;29:1897–903. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4647-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Yang H, Peckham E, Becker J. 2009 Neuroscience Meeting Planner. Society for Neuroscience; Chicago, IL: 2009. Investigation into the mechanisms mediating the rapid effect of 17ß-estradiol on dopamine release in the striatum. Program No. 771.1. Online. [Google Scholar]

- [23].Peris J, Decambre N, Coleman-Hardee ML, Simpkins JW. Estradiol enhances behavioral sensitization to cocaine and amphetamine-stimulated striatal [3H]dopamine release. Brain Res. 1991;566:255–64. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(91)91706-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Perrotti LI, Russo SJ, Fletcher H, Chin J, Webb T, Jenab S, et al. Ovarian hormones modulate cocaine-induced locomotor and stereotypic activity. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2001;937:202–16. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2001.tb03566.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Ito R, Robbins TW, Everitt BJ. Differential control over cocaine-seeking behavior by nucleus accumbens core and shell. Nat Neurosci. 2004;7:389–97. doi: 10.1038/nn1217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Kourrich S, Thomas MJ. Similar neurons, opposite adaptations: Psychostimulant experience differentially alters firing properties in accumbens core versus shell. J Neurosci. 2009;29:12275–83. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3028-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Norrholm SD, Bibb JA, Nestler EJ, Ouimet CC, Taylor JR, Greengard P. Cocaine-induced proliferation of dendritic spines in nucleus accumbens is dependent on the activity of cyclin-dependent kinase-5. Neuroscience. 2003;116:19–22. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(02)00560-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Li Y, Acerbo MJ, Robinson TE. The induction of behavioural sensitization is associated with cocaine-induced structural plasticity in the core (but not shell) of the nucleus accumbens. Eur J Neurosci. 2004;20:1647–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2004.03612.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Golden SA, Russo SJ. Mechanisms of psychostimulant-induced structural plasticity. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2012:2. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a011957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Vezina P, Leyton M. Conditioned cues and the expression of stimulant sensitization in animals and humans. Neuropharmacology. 2009;56(Supplement 1):160–8. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2008.06.070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]