Abstract

Mild traumatic brain injury (mTBI) is recognized as a prevalent and significant risk concern for youth. Appropriate school return is particularly challenging. The medical and school systems must be prepared partners to support the school return of the student with mTBI. Medical providers must be trained in assessment and management skills with a focused understanding of school demands. Schools must develop policies and procedures to prepare staff to support a gradual return process with the necessary academic accommodations. Ongoing communication between the family, student, school, and medical provider is essential to supporting recovery. A systematic gradual return to school process is proposed including levels of recommended activity and criteria for advancement. Targets for intervention are described with associated strategies for supporting recovery. A ten element PACE model for activity-exertion management is introduced to manage symptom exacerbation. A strong medical-school partnership will maximize outcomes for students with mTBI.

Keywords: Mild traumatic brain injury, TBI, youth, pediatric, concussion

The management of youth following a mild traumatic brain injury (mTBI) has no greater challenge or complexity than the return to their biggest “job” - school. Managing return to school post-mTBI is a multifaceted process without a specific body of research evidence to guide the process as of yet. Nevertheless, medical providers need practical management strategies to assist the student’s return to school. Equally important, school systems must be prepared to provide appropriate academic supports to recovering students. Managing mTBI in the school setting can borrow from other areas of research and practice until it has achieved its own evidence base. This paper discusses a practical approach to guiding school return, applying general principles and methods of symptom management. The goal is to provide both the medical provider and school system with a joint, collaborative approach to assisting the recovering student with their school reintegration. Following a brief introduction to the general issues of mTBI in children and adolescents, the paper is organized as follows: Preparing the medical and school systems to facilitate school return, partnering to guide the five-stage gradual return to school, and applying a 10-element activity-exertion management approach to facilitate recovery.

Increased awareness of mTBI in children and adolescents over the past several years has set the scene and established the necessity for this paper. Fundamentally, an expeditious, yet appropriately managed, return to school after mTBI is critical to the overall health and well-being of the recovering student. Time away from school can pose a significant threat to their academic and psychological well-being. School return following mTBI has gained initial attention over the past three years in clinical practice1,2 and in the public health arena as the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) toolkits address mTBI in schools via the “Heads Up to Schools: Know Your Concussion ABC’s”3,4,5. More so, recently, the American Academy of Pediatrics issued a clinical report6 to bring attention to school return issues following sport-related concussion to the pediatrics community. Though a scant evidence-based literature currently exists to guide the return to school process, we review the effects of an mTBI on the student’s school performance, and offer practical management strategies.

As the manifestation of an mTBI can vary significantly from student to student, a generic, cookie-cutter approach to mTBI management in the school setting should not be applied. Mild TBI may have certain commonalities in its clinical presentation but each has its own unique characteristics. The individualized assessment and treatment of the student’s clinical symptom profile must, therefore, be individualized7,8,9. The variability in clinical presentation and length of recovery poses a challenge to the medical provider and school to apply a student-specific plan of treatment and supports. To further complicate matters, there has been recent debate on the most effective approach to managing the mTBI recovery process10, in terms of an active or passive treatment approach. Traditionally, emphasis was placed on “rest” of both physical and cognitive activity7 with the justification that the neurometabolic derangement associated with mTBI11 required a restful period of time to re-establish equilibrium. Yet some argue that the application of rest as a treatment for mTBI may have been taken to an extreme. Questions are now being asked as to how much rest should be prescribed, at what point in time, and for how long should it be applied12. An overreliance on extended periods of total or near-total rest as the primary or sole treatment modality after the acute injury phase has sparked questions about its efficacy in facilitating recovery, and with its over-application possibly interfering with recovery. These issues are critically important to consider when planning the student’s return to school. This paper takes a practical approach to the “activity-rest” debate and proposes a management model that balances both in a monitored manner.

As backdrop to the school issues, the recent reports of the Institute of Medicine (IOM)13 and the evidence-based sport concussion guidelines of the American Academy of Neurology (AAN)14 concluded that little solid research evidence related to outcomes of youth mTBI exists upon which to base management strategies. At the high school and college levels, available statistics for sport-related mTBI indicate the large majority of male athletes (85%) recover over a period of 1–3 weeks15. Outcome data such as the duration of recovery is lacking, however, for younger athletes, females and other injury causes and mechanisms. If these timeframes do, in fact, apply to most mTBIs across the school ages, the amount of time that a student requires an academic support plan will be relatively short in duration, relative to other educational handicapping conditions. Nevertheless, most students with mTBI will require some level of academic support for a short time period, with a smaller percentage requiring more significant supports over a longer duration. Presently, early post-injury it is difficult to predict which students will manifest a prolonged, complicated recovery pattern. Ultimately, a better understanding of these early predictors of recovery outcome and duration will assist the medical provider in choosing the most appropriate, tailored management strategy from the outset. This knowledge will also allow the school to plan more proactively for the student’s academic support needs. In the meantime, we must rely on practical and logical guidance to manage the student’s recovery and associated return to school.

Themes in Preparing the School Support System

A smooth reentry into school following any medical issue is critically important for the student given its central importance in their life. A well-prepared medical-school partnership is essential to implement proper management following an mTBI. To provide guidance for this partnership, we examined the school return program materials for several other pediatric neurologic and medical disorders. Students with migraine headaches can find guidance in the document “Migraines and Going Back to School - 10 Tips,” an unpublished set of guidelines by Teri Robert in 2012. Similarly, the Epilepsy Foundation of America, the American Diabetes Association, and the National Asthma Education & Prevention Program have produced materials to guide a smooth return to school.

A review of these materials reveals six common themes that can be applied to students with mTBI: (1) formal education and training of school personnel regarding the nature of the condition, its effects on school learning, and the types of supports and accommodations that can be provided; (2) definition of the roles of school personnel, family, and student serve with respect to the activities and strategies that support recovery; (3) preparation of the school environment, recognizing possible triggers of medical problems or symptom exacerbation while maintaining a normalized environment whenever possible; (4) the use of standardized forms or materials to guide teaching staff in the symptoms to monitor, the specific supports to provide to the student, and the conditions for communication with parents; (5) development and active use of a student-specific medical management plan that ties together the student’s individualized needs and plan of accommodations; and (6) regular, ongoing communication between the medical provider, school, student and family to assure understanding of the student’s evolving medical, academic and social-emotional support needs.

The common themes in these materials illustrate the important point that effective management and support of the student starts with well-prepared and coordinated medical and school systems. These six key themes can be applied directly to the family and student with mTBI in their return to school.

All medical providers and key school personnel should be trained for their specific role in the support of the student with mTBI, with a focus on manifestations in the school setting.

The student with an mTBI shall receive an initial medical evaluation to guide management, including definition of their symptom profile (type and severity), with ongoing monitoring of symptom status through to recovery.

A school mTBI team must be defined, skilled in translating the student symptom profile into academic supports/ accommodations.

The student symptom profile will be communicated directly by the medical provider to the mTBI-trained school team using a student-specific mTBI management plan.

Periodic in-school monitoring of symptom progress will be conducted, adjusting supports accordingly.

Regular, ongoing communication occurs between the family, medical provider, student, and school regarding the student’s symptom status and progress.

Medical System Preparation

The student who sustains an mTBI may enter into the medical system at a number of different points, including the pre-hospital emergency medical system, emergency department/trauma service, urgent care system, primary care office, or specialty care (e.g., neurology, sports medicine) system. Although each point of entry may not necessarily play the same role in the return to school process, each has a responsibility for addressing the question of return to school via discharge teaching/ patient instruction. In the same way that planning for return to work is critical for injured adults in the Emergency Room setting, so must return to school planning be considered a necessary issue to address at each level of medical care.

Training Resources for Medical Providers

Inconsistency exists in the extent to which medical providers are prepared to translate their medical findings into meaningful, individualized school supports for students. Fortunately, resources exist to address this need. As general preparation, all healthcare providers that interact with students who sustain an mTBI should take advantage of the CDC education and training resources for mTBI (www.cdc.gov/concussion). Training in the assessment and management of mTBI can be obtained through the “Heads Up: Brain Injury in Your Practice” toolkit16 within which tools such as the Acute Concussion Evaluation17 can be accessed. These materials can be supplemented by the online video instruction of the evaluation and management of mTBI in the “Heads Up to Clinicians: Concussion Training” program. The Acute Concussion Evaluation (ACE)17,18 and the Sport Concussion Assessment Tool, 3rd Edition (SCAT3)19 were developed to guide the medical provider through a standard protocol for assessing these key elements of mTBI.

Evaluation of mTBI requires obtaining a solid definition of the injury characteristics (i.e. cause and mechanism of injury; presence of loss of consciousness, retrograde/ anterograde amnesia, and early signs), a review of pre-morbid and post-injury risk factors that may influence recovery, and a thorough assessment of all post-concussion signs and symptoms18. This evaluation provides the definition of the student’s symptom profile, which then can be communicated to the school for translation into school support recommendations. To further prepare oneself on the school-related manifestation of mTBI, the medical provider is directed to the CDC “Heads Up to Schools: Know Your Concussion ABCs” toolkit.3

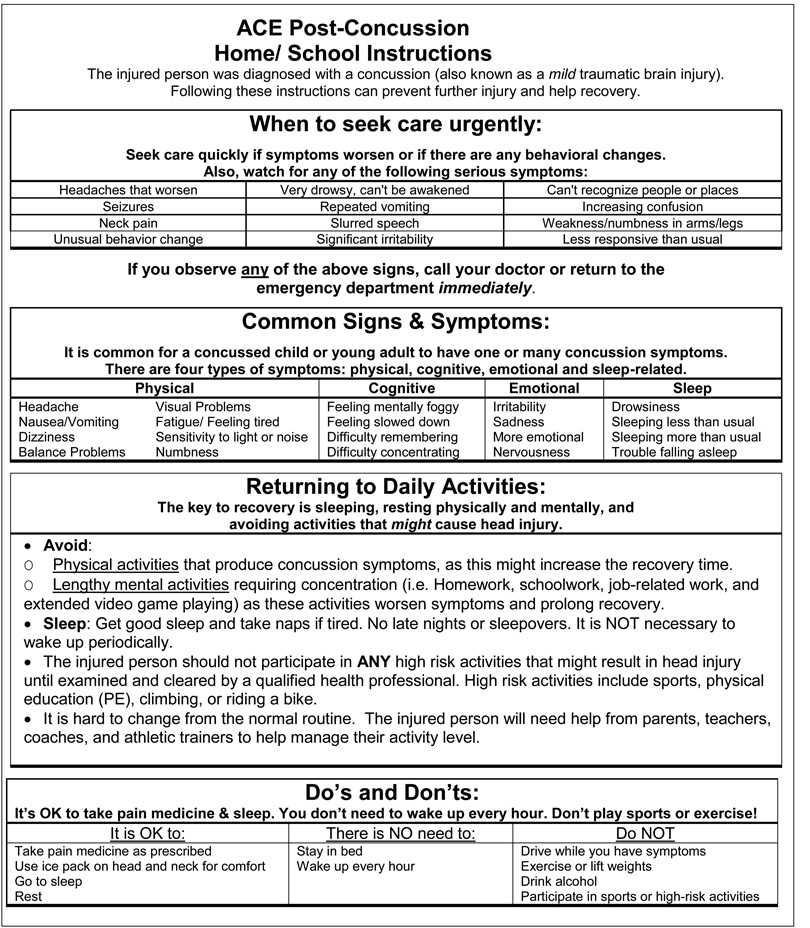

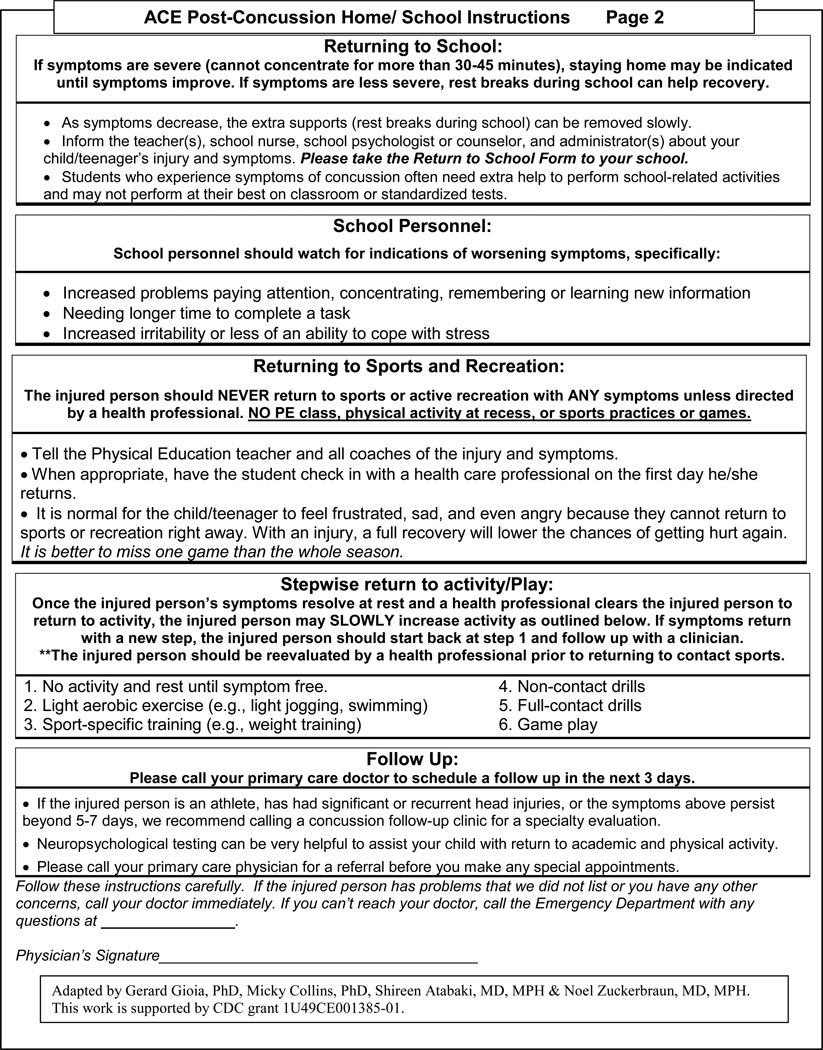

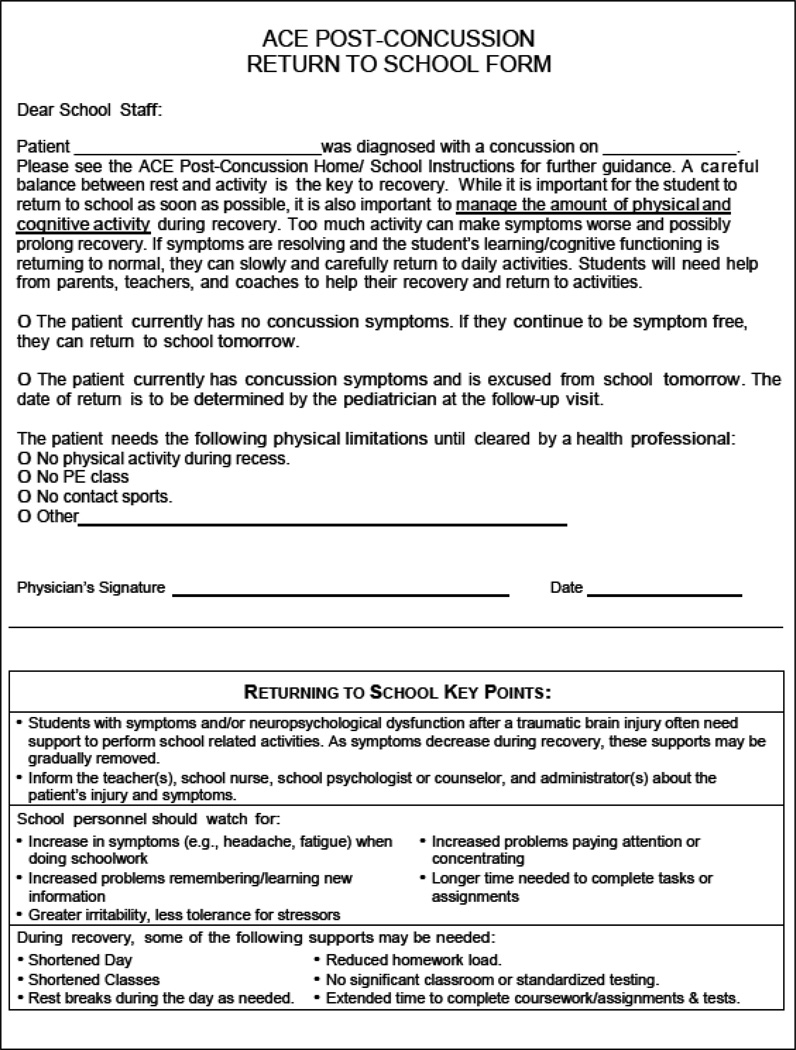

Early post-injury, medical providers are typically posed with several key questions when considering school management planning: (1) When should the student return to school? How long should they remain out of school? (2) When the student returns to school, should it be for a full day or partial day? If a partial day is recommended, how and when should they transition into a full day? (3) What types of in-school accommodations should the student receive and for how long? (4) What tools are available to guide Return to School planning? These questions are best addressed in concert with the mTBI-prepared school personnel. In sections that follow, we discuss the schools’ preparation to address these issues as well so that educated management decisions can be made on behalf of the student. To assist the medical provider in making school-related management recommendations, two discharge planning tools are available to the medical provider. The ACE Post-Concussion Home/School Instructions (See Appendix A) was developed via a CDC-funded study for acute guidance in the first few days post-injury, providing standard, universal instructions to families and schools. After the acute stage of the injury, the ACE Care Plan16,18 was developed as companion tool to the ACE to provide more individualized management guidance.

Mild TBI-specific discharge instructions can have a positive impact on the student’s general recovery and return to school. We demonstrated this effect in a recent CDC-funded study addressing acute mTBI assessment and management within the Emergency Department (ED). The effectiveness of the ED-modified Acute Concussion Evaluation (ACE-ED) tools was examined in guiding the post-injury follow-up of patients, age’s 5–21 years20. The post-acute ACE Care Plan tool was modified for the acute care setting to become the ACE Post-Concussion Home-School Discharge Instructions to guide early management of daily life, school, work and return to sport issues. Additionally, a Return to School Form (see Appendix B) was used to guide the return to school process, alerting school personnel to key problems and symptoms, as well as the potential need for school supports. The study was designed such that one-half of the sample received the ACE-ED discharge instructions and Return to School Form while the other half received standard general guidance. The ACE-ED intervention group, when compared to the standard care group, demonstrated improved medical follow-up care at 1, 2 and 4 weeks post-injury (e.g., 32% vs. 61% at Week 4, p<0.001) with a significant increase in parental recall of the discharge instructions. With explicit instruction, parental recall of concussion symptom education, activity restrictions, and sports recommendations was significantly increased.

Importantly for the purposes of this paper, the largest effect was found in the parents’ recall of instructions for school management. The median number of school days missed post-injury was only two days in both groups. Two-thirds of parents in the ACE-ED intervention group reported using the ACE-ED Return to School form, and a greater number of children in this group reported receiving academic supports than the standard care group (17% vs. 4%; F=19.5, p<.001, eta2=.06). Report of return to normal activity was significantly longer, which was likely the result of greater information about the child’s symptom status guiding post-injury activities. Overall, this study highlights the significant benefits of patient-specific, symptom-based management guidance for overall recovery and the student’s return to school.

School System Preparation

As just described, the trained medical provider initiates the process of school return by defining the student’s symptom profile, making an early determination regarding gradual return to school process, and providing initial management guidance. We now turn our attention to the preparation of the school to receive the injured student and provide appropriate supports. The student’s academic needs can be effectively addressed only through a prepared school system skilled in translating the student symptom profile into academic supports and accommodations.

Schools and school systems currently vary widely in their understanding of mTBI, its academic, physical, and social-emotional manifestations, and the types of supports available for students. On the positive side, active school supports for the student with mTBI has improved over the past ten years. There remains, however, a national need to implement systematic school-based concussion awareness, education, and management programs. While Traumatic Brain Injury is an explicit category for special education eligibility, students with mTBI typically do not meet the criteria for services under this mechanism. Mild TBI can, therefore, fall into an undefined service gap. Few state and local education agencies have formal policies and procedures for service delivery to support the academic needs of the student with mTBI.

To fill this service gap, three programmatic recommendations are offered to implement a top-down school-based academic mTBI management program: (1) establish state and local school policies and procedures for the identification and academic management of students with mTBI, (2) educate school personnel about mTBI, including formation and role definition of the school-based team, and, (3) implementation of school-based concussion management action plans. Just as in other accommodation-based educational service plans, each student’s needs require individualization, involving the cooperation and coordination of multiple school personnel with ongoing assessment and adjustment of the plan through the timeline of recovery. Table 1 outlines the processes for a school-based mTBI management program, with delineation of responsible parties, and the benchmarks for completion.

Table 1.

School Concussion Management: Activities & Responsibilities*

| Activity | Responsible Parties | Evidence of Completion |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Concussion Management Policies & Procedures (P & P) | School Administration [school nurse, counselor, psychologist] | Written policy in school manual; copy provided to all school staff |

| 2. Development of School Concussion Resource Team | School Administration; school nurse, counselor, psychologist, designated teacher, athletic trainer | Written policy in school manual |

| 3. Examine teaching/support methods to support recovery, maximize learning/performance, reduce symptom exacerbation | School Administration; school nurse, counselor, psychologist | Written policies on teaching methods |

| 4. Teacher/Staff Education & Training (online video training, CDC School Professional Fact Sheet) | Teacher, School Counselor, School Nurse, Administrators | Verification of completion provided to school administration |

| 5. Develop list of concussion resources for education, consultation & referral (medical, school, state/local Brain Injury Association) | School administration | List of resources provided in P & P; available to school staff & families |

Adapted from Sady et al. 2011

The development of mTBI management policies and procedures is the first step to help returning students succeed as they recover from a concussion with attention paid to the six themes common to the various medical and neurologic conditions described above. Policies would address: (1) a brief description of mTBI/ concussion, (2) definition of the school “receiving team” to guide reentry, (3) the gradual process to assist the student’s return into school life (learning, social activity, etc.), and (4) criteria for when students can safely return to physical activity and full cognitive activity. A school-based action plan must be in place before the start of the school year based on these policies and procedures to ensure that all students are appropriately served once identified. School and athletic staff should be fully informed of the plan and trained in its implementation via in-service training.

The second step in developing a school- or system-wide concussion management program involves educating school personnel about (1) concussions and their effects, and (2) each professional’s role in management when an injury occurs. Ideally, concussion education would occur prior to the start of the school year so that teachers, counselors, administrators, coaches, and nurses alike are prepared to support a concussion when it occurs. All school staff should be familiarized with the general principles for supporting the student’s return, including classroom teachers, PE teachers, coaches, and staff that supervise free time such as lunch and recess. It is critical to identify the key school personnel and define the roles each will play to support the student’s return. Although individual schools may vary, key team members might include the school nurse/ health aide, school counselor, school psychologist, speech/language pathologist, athletic trainer (high school level), PE teacher and a school administrator. School policies should specify how school personnel will be informed about a returning student’s injury and specific symptoms, and ways they can assist with the student’s transition process and making accommodations for a student. At present, most schools typically do not have a coordinated team with definable roles, including a school-medical liaison, prepared to support the recovering student from the outset of the injury. The aforementioned CDC “Heads Up to Schools: Know Your Concussion ABCs3” toolkit materials are available to assist the education and training of school personnel. Specific accommodations can be found from a variety of sources, including the CDC “Helping Students Recover from a Concussion: Classroom Tips for Teachers.5” It is further recommended that school systems engage an mTBI expert to provide in-service education and training to school-based personnel at the elementary, middle and high school levels.

Each school is potentially unique in their personnel, duties, skillsets, and interests. As a result, there is not a “one size fits all” concussion management plan for every school, but the same goals of supporting the student’s return nevertheless apply. The gradual return to school plan and the aforementioned program components and processes should be adapted in whatever way is most effective. Each effective management plan must involve the injured student, their parents, and a carefully coordinated team of school personnel. One person should serve as the medical lead (e.g., nurse, school psychologist, or athletic trainer) regularly track symptoms, looking for improvement or worsening, and communicating these changes to the rest of the team. The student’s guidance counselor or school psychologist can then coordinate cognitive/ academic accommodations, using a symptom log to track and guide adjustments. In addition to self-reported symptoms, the student’s teachers should also be observant of the potential cognitive and emotional effects of injuries such as increased problems paying attention or concentrating, greater challenges remembering or learning new information, needing more time to complete tasks or assignments, greater irritability and less tolerance for stressors, and the possibility of increased symptoms (i.e., cognitive exertional effects such as headache and fatigue) when doing schoolwork. Throughout the course of recovery, it is essential that students receive a consistent, supportive, and positive message from all school staff about expectations and accommodations during recovery.

Partnering to Guide the Gradual Return to School

With an established partnership between the mTBI-prepared medical and school systems, effective and efficient communication of the students' needs can occur. The student’s symptom profile can be communicated to the mTBI-trained school team via such tools as the symptom table of the ACE and the ACE Care Plan or the SCAT3. As the student progresses in their recovery, periodic in-school monitoring of symptom progress can be conducted using, for example, the CDC’s Concussion Signs and Symptoms Checklist of the school toolkit3, adjusting the supports accordingly as the student moves through the gradual return process. This dynamic process necessitates regular communication of student status/ progress between the family, medical provider, student and school. Next, we describe the five stages of the gradual return to school process followed by the key targets for student support and treatment.

Stages in the Gradual Return to School Process

Starting from the point of injury, a gradual return to school process is recommended. Table 2 highlights the stages of gradual return, including proposed decision criteria for moving to the next stage. This progression should be coordinated between the medical provider and school personnel as the student’s recovery and associated level of support is a shared activity. Importantly, the plan is dictated by the student’s symptom status (number and severity of symptoms) – and their tolerance for activity. At the outset, the medical provider most likely will make the recommendation for the initial stage of return, but ongoing decisions about progression through the gradual return process requires active school involvement, symptom monitoring, and depends on the student’s progress in the school setting. Importantly, although six sequential steps are outlined, recovery patterns for any given student can vary. Depending on the student’s speed of recovery, they may not need to progress through each stage if their symptom status does not dictate it. In addition, the length of time required at any given stage will be individually determined by their symptom status and pace of recovery. This point highlights the critical importance of regular, periodic individualized monitoring and re-assessment of the student to provide the appropriate type and amount of school support. Flexibility in the application of the gradual school return plan is essential. For example, many students will likely need to stay home only one or two days (Stage 0) immediately following their injury with a steady reduction in symptoms during that time such that they can likely progress relatively rapidly to a full day with moderate supports (Stage 3). At the same time, more severe or complex injuries may require a longer stay at home due to significant persistent symptoms that are not resolving in a typical manner. In an even smaller number of cases, Homebound Instruction, provided by the school system, may be necessary.

Table 2.

Gradual Return to Academics

| Stage | Description | Activity Level | Criteria to Move to Next Stage |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | No return, at home | Day 1 - Maintain low level cognitive and physical activity. No prolonged concentration. Cognitive Readiness Challenge: As symptoms improve, try reading or math challenge task for 10–30 minutes; assess for symptom increase. |

To Move To Stage 1: (1) Student can sustain concentration for 30 minutes before significant symptom exacerbation, AND (2) Symptoms reduce or disappear with cognitive rest breaks* allowing return to activity. |

| 1 | Return to School, Partial Day (1–3 hours) | Attend 1–3 classes, with interspersed rest breaks. Minimal expectations for productivity. No tests or homework. | To Move To Stage 2: Student symptom status improving, able to tolerate 4–5 hours of activity with 2–3 cognitive rest breaks built into school day. |

| 2 | Full Day, Maximal Supports (maximal supports required throughout day) | Attend most classes, with 2–3 rest breaks (20–30’), no tests. Minimal HW (< 60’). Minimal-moderate expectations for productivity. | To Move To Stage 3: Number & severity of symptomsimproving, needs only 1–2 cognitive rest breaks built into school day. |

| 3 | Return to Full Day, Moderate Supports (moderate supports provided in response to symptoms during day) | Attend all classes with 1–2 rest breaks (20–30’); begin quizzes. Moderate HW (60–90’) Moderate expectations for productivity. Design schedule for make-up work. | To Move To Stage 4: Continued symptom improvement, needs no more than 1 cognitive rest break per day |

| 4 | Return to Full Day, Minimal Supports (Monitoring final recovery) | Attend all classes with 0–1 rest breaks (20–30’); begin modified tests (breaks, extra time). HW (90+’) Moderate- maximum expectations for productivity. | To Move To Stage 5: No active symptoms, no exertional effects across the full school day. |

| 5 | Full Return, No Supports Needed | Full class schedule, no rest breaks. Max. expectations for productivity. Begin to address make-up work. | N/A |

Cognitive rest break: a period during which the student refrains from academic or other cognitively demanding activities, including schoolwork, reading, TV/games, conversation. May involve a short nap or relaxation with eyes closed in a quiet setting.

It is recommended that most symptomatic students start at Stage 0 – No Return, At Home - for a day or two after the mTBI - and maintain a low level of cognitive and physical activity, engaging in no activities that demand prolonged concentration at least for the first day. In the first post-injury day, it can be difficult to know how the student will respond to the cognitive and physical demands of school. Having a controlled home environment can be helpful to make the determination of their readiness to return. The student’s level of symptoms should be carefully assessed during this early post-acute period. As symptoms improve and become more tolerable with respect to daily activities, it is recommended that their sensitivity to school-like cognitive activity in the controlled home environment be assessed. This can be accomplished by engaging the student in a “Cognitive Readiness Challenge” task such as a reading or math assignment for 10–30 minutes. Assess for symptom increase during or after the task as this will give an indication of the student’s tolerance for classroom activity. The proposed criteria for return to school is defined as the student tolerating at least 30 minutes of cognitive activity with only mild symptom exacerbation, and with a reduction of symptoms after a rest period from cognitive activity. Thirty minutes is chosen as this represents the greater part of a typical class period. A positive response to the cognitive rest break is an important criterion as this reduction in symptoms will allow the student to return to class to continue productive learning activity. A “cognitive rest break” is defined as a period during which the student refrains from academic or other cognitively demanding activities, including schoolwork, reading, TV/games, conversation. For some students, this period also may involve a short nap or relaxation with eyes closed in a quiet setting free of excessive stimulation.

Stage 1. Return to School, Partial Day: At this stage, the student demonstrates that they can tolerate between one to three classes (up to one-half of the day) with interspersed rest breaks of 20–30 minutes. At this stage, the main goal is for the student’s return to the routine of school attendance although there should be minimal expectations for academic productivity due to a significant symptom burden. No homework would be assigned at this stage and the student would not participate in any quizzes, tests or exams. The criteria for moving to the next stage, a full day of school, would be improving symptom status where the student can tolerate attendance in class for up to 4–5 hours per day with 2–3 cognitive rest breaks built into the school day.

Stage 2. Return to School, Full Day, Maximal Supports: The student is now able to handle the physical and cognitive demands of most of the school day but symptoms are still significant enough that maximal supports are necessary such as 2–3 rest breaks, no tests or quizzes, and homework of less than one hour. Expectations for productivity would be minimal to moderate. With continued improvement in the number and severity of symptoms, as indicated by the regular, ongoing monitoring, supports can be reduced to a moderate level with a move to the next stage.

Stage 3. Return to School, Full Day, Moderate Supports: At this stage, symptoms are improving and the student can attend all classes, but continues to require 1–2 cognitive rest breaks across the day. Given the reduced symptom status, the student can now begin to take quizzes and the duration of homework can be extended to 90 minutes (in 20–30 minute increments). Expectations for academic productivity also can increase. At this point, depending on how long the student has been restricted in their academic program, a schedule for make-up classwork, homework, and tests will need to be devised. The teaching faculty may need to decide what the essential is to be made up, especially if the volume of work is significant. In the experience of this author, making up missed work is one of the most stressful aspects of concussion recovery, necessitating that it be handled carefully with the student.

Stage 4. Return to School, Full Day, Minimal Supports: At Stage 4, the student now requires minimal supports and may need one or less rest break during the day. They can handle most of the work demands, including beginning to take modified exams as their symptoms require (e.g., given extended time to complete the exams, with possible breaks built in). Homework requirements are now nearing their typical level, although the student must be sure not to stay up late at night and interfere with their critically important sleep requirement. Once symptoms have fully resolved with a full day of school demands, the student can proceed to the final stage.

Stage 5. Return to School, Full Day, No Supports: At this point, the student has no active symptoms and no exertional effects across the full school day. They can manage a full class schedule with the need for no rest breaks. Expectations for academic productivity have returned to the pre-injury level. At this time, the previous schedule for make-up work should be reviewed, modified as necessary, and initiated.

Targets for Student Support and Treatment

When considering the types of academic needs and supports that the student may require, two primary and related targets should be considered: (1) how the mTBI affects the neuropsychological functions that impact school learning and performance, and (2) the effect that school learning and performance may have on symptom expression. For the former, we describe the types of academic accommodations and adjustments that can be provided in the classroom. For the latter, we describe a strategy to manage the student’s activity-exertion relationship effectively, allowing maximal school participation.

Academic needs and accommodations. A variety of cognitive and behavioral/ emotional impairments frequently accompany an mTBI. The cognitive impairments include poor attention/concentration, working memory, new learning and memory, speed of information processing, and executive functioning, while the behavioral/emotional issues include increased irritability, poor mood regulation, and poor control of emotional response to stressors. To further define how these impairments manifest in school, we asked a clinic sample of elementary, middle and high school students with mTBI (n=216) to describe the new-onset problems they were having in school. They reported in-school cognitive problems paying attention (58%), understanding new material (44%), and slowed performance completing homework (49%). In addition, they reported headaches interfering with learning (66%) and fatigue in class (54%). High school students reported more of these in-school problems relative to the younger grade levels. A higher number of reported school problems were correlated with a higher symptom burden on the Post-Concussion Symptom Inventory, indicating that the more symptomatic students tended to struggle the most in school.

To support these in-school challenges, the medical provider can recommend specific classroom accommodations and adjustments such as modifying the length of assignments, giving extended time to complete tasks, and providing classroom notes to the student who cannot keep pace with note-taking in a lecture. Table 3 provides a set of academic accommodations that correspond to the range of neuropsychological impairments that affect school learning and performance. For example, difficulties with working memory can result in holding instructions and other information in mind, affecting school tasks such as reading comprehension, math calculation, and writing. Accommodations can include repetition of the information in class, providing written instructions to support oral, use of a calculator, and shortened reading passages. Table 4 offers accommodations to address physical symptoms that can affect learning and performance in school. For example, light and noise sensitivity can produce a worsening of symptoms in bright or loud environments. Accommodations might include the student wearing sunglasses, sitting away from the bright sunlight or other noxious classroom lighting. They might also avoid noisy or crowded environments such as the lunchroom, assemblies, hallways in favor of quieter environments.

Table 3.

Accommodations for Post-Concussion Neuropsychological (Cognitive and Emotional) Symptoms Affecting School

| Post-Concussion Effect |

Functional School Problem |

Accommodation/Management Strategy |

|---|---|---|

| Attention/Concentration | Short focus on lecture, classwork, homework | Shorter assignments, break down tasks, lighter work load |

| “Working” Memory | Holding instructions in mind, reading comprehension, math calculation, writing | Repetition, written instructions, use of calculator, short reading passages |

| Memory Consolidation/Retrieval | Retaining new information, accessing learned info when needed | Smaller chunks to learn, recognition cues |

| Processing Speed | Keep pace with work demand, process verbal information effectively | Extended time, slow down verbalinfo, comprehension-checking |

| Cognitive Fatigue | Decreased arousal/activation to engage basic attention, working memory | Rest breaks during classes, homework, and exams |

| Anxiety | Interferes with concentration; Student may push through symptoms to prevent falling behind | Reassurance from teachers and team about accommodations; Workload reduction, alternate forms of testing |

| Depression/Withdrawal | Withdrawal from school or friends due to stigma or activity restrictions | Engage student with friends at lunch or recess, build in time for socialization |

| Irritability | Poor tolerance for stress, alienate peers or teachers | Reduce stimulation and stressors, provide rest break |

Table 4.

Accommodations for Post-Concussion Physical Symptoms Affecting School

| Post-Concussion Effect |

Functional School Problem |

Accommodation/Management Strategy |

|---|---|---|

| Headaches | Interferes with concentration, increased irritability | Rest breaks, short nap |

| Light/Noise Sensitivity | Symptoms worsen in bright or loud environments | Wear sunglasses, seating away from bright sunlight or other light.Avoid noisy/crowded environments such as lunchroom, assemblies, hallways. |

| Dizziness/Balance Problems | Unsteadiness when walking | Elevator pass, class transition prior to bell |

| Sleep Disturbance | Decreased arousal, shifted sleep schedule | Later start time, shortened day |

| Symptom Sensitivity (exertional effects) |

Symptoms worsen with over-activity, resulting in any of the above problems | Reduce cognitive or physical demands below symptom threshold; provide rest breaks; complete work in small increments until symptom threshold increases |

Additional recommendations for classroom accommodations can be found in several other excellent resources including the CDC handout “Helping Students Recover from a Concussion: Classroom Tips for Teachers5,” Brain 101 School-Wide Concussion Management Program (http://brain101.orcasinc.com)21 and the Colorado REAP program22.

Management of Exertional Effects. The second target for intervention encompasses managing the exertional effects that the student may experience in response to the cognitive, emotional and physical demands of the school setting. As background to this intervention strategy, we advocate for “optimal” activity (i.e., maximal activity with minimal symptoms) during recovery. We recognize that active treatment approaches to mTBI currently are in their earliest stages of research and understanding as outlined in the recent AAN evidence-based review14. Nevertheless, the “active rehabilitation” model of mTBI treatment has gained increasing interest12,23,24. In applying an active rehabilitation model of treatment, an individualized approach is essential taking into account the type and severity of the biomechanical injury, symptom pattern, and patient history that potentially modifies the injury and symptoms. A thorough evaluation of the student’s physical, cognitive and emotional history and post-concussion symptoms is essential to guide an effective school-based rehabilitation program.

As a foundation, mTBI is generally viewed to be an injury to the neurometabolic/ neurotransmission mechanisms of the brain with a significant crisis in terms of available energy to perform one’s typical everyday cognitive and physical activities10. Recovery is hypothesized to be the gradual re-establishing of the brain’s equilibrium with respect to these neurometabolic/ neurotransmission functions. A generally accepted treatment recommendation is to refrain from engaging in activities that significantly worsen one’s symptoms. Symptom exacerbation following physical or cognitive activity is commonly reported and is hypothesized at least in the early post-acute phase to be a signal that the brain’s dysfunctional neurometabolism is being pushed beyond its tolerable limits25. Periods of prolonged concentration, class work, homework or lengthy classes have the potential of producing an increase in symptoms such as headaches, fatigue or decreased concentration. As with other aspects of mTBI, these “exertional effects” can vary from person to person, task to task and across recovery, necessitating an individualized assessment of the student’s cognitive exertional response. We sought to determine how common exertional effects were reported in our concussion clinic population and found that 62.5% of high school students (n= 206) reported a worsening of their post-mTBI symptoms with cognitive demands in school26. This level of exertional response would suggest that in order to optimize the student’s academic productivity and well-being, active management of the cognitive exertional effects must be attended to.

Activity-Exertion Management Process. To manage these exertional effects, we propose a practical symptom management approach based on therapeutic principles used in the field of pediatric psychology with other medical disorders such as pain, acute and chronic illness27. We recognize that further research is necessary to establish full efficacy of this approach but believe that its foundation with other medical illnesses provides justification for its application to the patient with mTBI. The goal of this approach is to teach the patient and family an active, positive and progressive approach to manage their symptoms. In the case of mTBI, the intervention focus is on the progressive management of “optimal” cognitive and physical activities, while monitoring and supporting the student’s emotional response, to avoid significant symptom exacerbation. The therapeutic strategy is intended to engage the student back into their school and social activities maximally and confidently while not significantly worsening symptoms. At the very least, this approach aims to reduce the adverse effects of increased symptom levels, which can further impair learning and performance and increase anxiety, yet engage the student in their school program to the maximum extent possible.

In guiding recovery in the school, therefore, management of the student’s type and degree of cognitive and physical activity is central, not allowing the hypothesized neurophysiologic threshold to be exceeded, and keeping symptoms in check. Yet, another critical feature to guiding recovery is not to reinforce the child for being too underactive. Thus, the strategy for the medical provider is to positively encourage the child to engage in cognitive and physical activities that are tolerable but do not significantly worsen symptoms. This moderated, “optimal” activity strategy (“Not too much, not too little”) gains preliminary support from Majerske et al.28 who found better mTBI outcomes in recovering patients that we not too underactive or overactive.

To achieve this goal, the student and family must be taught a strategy for coordinating activity level with exertional effects (i.e., activity-exertion management). In doing so, the student’s pre- and post-injury cognitive and emotional developmental status must be considered. Younger children can be taught basic strategies for monitoring symptoms but likely need significantly more guidance and direction than the more cognitively sophisticated adolescent. Individual differences in exertional effects also must be considered. Some students are able to perform certain tasks more automatically, requiring less exertion. For example, the more proficient reader may be able to tolerate a greater amount of reading (i.e., manifest less of an exertional increase in symptoms) than the less proficient reader. One would not want to over restrict this more capable reader. Relatedly, reading a pleasure book requires less exertional concentration than reading a history book for facts. The point here is that the person’s skill levels and the type/ intensity of the activity must be understood when considering the activity-exertion relationship. As another example, a youngster with a history of Attention-Deficit/ Hyperactivity Disorder may also require greater constraints or structure applied to their activity-exertion management plan to ensure that they do not impulsively overexert in their daily activities. Finally, the student’s emotional history is a critical factor to take into account when planning the treatment strategy, especially if there is a history of anxiety or mood disorder. Children with such a history may require special supports to encourage their active, constructive participation in the rehabilitation program as there may be a tendency toward greater sensitivity to symptoms. Other motivations should be considered in guiding the student’s recovery plan, such as the student with impending academic deadlines that may push them to exceed their capabilities (e.g., engaging in hours of sustained homework, staying up late multiple nights to finish homework or projects to the detriment of their sleep). Needless to say, an individualized approach is essential, based on the student’s pre-injury factors and post-injury symptom status.

Ten Elements for mTBI Activity-Exertion Management

As the student progresses through an individualized gradual return to school program with tailored academic accommodations, the medical-school alliance must assure a careful balance between increasing cognitive/ physical activity and controlled exertion. The student must learn the skills of activity-exertion management. To facilitate this learning, we introduce the Progressive Activities of Controlled Exertion (PACE) model that articulates ten elements to structure this positive, progressive treatment approach. As already noted, the medical provider must have an understanding of the student’s unique injury, developmental, medical, emotional, and family situation as well as the school environment to tailor the plan appropriately. The 10-element PACE model is offered for two reasons: to provide clinicians with a script to use in an active, progressive management approach, as well as a possible structure for future research. The PACE model is developed for use by the medical provider and school personnel, especially the school nurse, psychologist, and guidance counselor who may be responsible for its implementation, oversight and regular modification in the school setting. The ten-element PACE model is organized into four conceptual stages: (1) setting the positive foundation for recovery, (2) defining the parameters of activity-exertion management across the day and week, (3) teaching activity-exertion monitoring skills, and (4) reinforcing positive progress toward recovery.

Set the Positive Foundation (Elements 1–3)

Provide the student, family, and school with a psychologically positive, active problem-solving context for rehabilitation. Use frequent statements such as “You will improve and recover.” “Your efforts to manage your activity and time will pay off.” “Recovery is the light at the end of the tunnel, and you will reach it.” “You have control of your activity.” Highlight for the child and family symptoms that may have already resolved or are improving as evidence of progress toward recovery. Framing the injury and its recovery in a positive, constructive, reassuring manner is critical.

Explore and manage the emotional response of the child and family to the injury. Assess how it has disrupted their lives. Ask what stresses or demands they are facing (school, peer, athletics). How do they typically manage stress? What do they know about mTBI and its effects? What have they heard about mTBI, and how is this affecting a positive, constructive, active approach to recovery? What fears or anxieties do they have about the injury and its effects? Correcting non-productive or incorrect thoughts/ knowledge about mTBI (e.g., one injury will result in long-term brain damage) is critical. (See the developmentally appropriate education in #3.) Realigning the emotions associated with these errant thoughts in a positive, constructive direction is essential to an active approach to recovery.

Provide developmentally appropriate education regarding mTBI and its dynamics (i.e., software injury), including the typical timeframes for recovery (i.e., typically days to several weeks) and the relationship between the student’s level of activity and the potential for symptom exacerbation (exertional effects). Types of exertion are reviewed: physical, cognitive, emotional – and the need to manage their energy demands. This knowledge serves as the basis for teaching the concepts of moderated “optimal” activity, managing the activity-exertion relationship, and sub-exertion effects threshold.

Define Parameters of Activity-Exertion Schedule (Elements 4–5)

Define the student’s typical daily schedule (before, during, after school, weekends), including the times of the day when activities might present the greatest exertional challenges (“hot spots”) and lesser challenges (“cool spots”). Next, define the specific type, intensity and duration of cognitive and physical activities within the schedule and their exertional effects on symptoms (e.g., “first period is a 60 minute Algebra class, which is very hard for me because there is a long lecture and my headaches increase a lot.” vs. “second period is a 60 minute Art class where we work at our own pace on our sculpture project, and I feel fine.”). This definition allows the medical provider to target the most troublesome or symptom-eliciting activities, and can be used to teach the student the specific activity-exertion connection. Possible symptom triggers are also defined - e.g., sensitizing/ exacerbating environmental stimulation (sound, light).

Define the limits of tolerability for activity intensity/duration - i.e., where symptoms do not increase substantially/ meaningfully. Ideally, this should be done for each key class. A sample question might be “How long can you typically go in your classes before you notice your symptoms become much worse and affect your learning?” Use these time / intensity limits as the frame within which to schedule the “work-rest” breaks.

Teach Activity/ Monitoring/ Management Skills (Elements 6–8)

Teach the concept of engaging in “Not too little, not too much” activity. The student’s goal is to find the activity “sweet spot” where activity time and effort are maximized without symptoms worsening. In other words, teach the related concepts of moderated activity and symptom management. It is important to emphasized to the student, parents and teachers that small increases in symptoms (e.g., where exertion ratings change by 1) are not counterproductive to recovery but large increases may be.

Teach “reasonable” symptom monitoring and recording. Be aware of the child or parent that is either an overly anxious over-reporter or an oblivious under-reporter, and coach them accordingly to monitor symptoms reasonably. For example, counsel the over-reporter to tolerate a bit more of the symptoms, and the under-reporter to attend a bit more closely to their symptom exacerbation.

Instruct the student to work up to their symptom limits, but to not exceed them, by being aware of (i.e., reasonable monitoring) their symptoms. When the symptoms increase several points on their exertion monitoring scale, take a defined rest break. Emphasize that tolerating a mild increase in symptoms is OK, but too much increase is not. When symptoms return to “typical” levels, they should return to the activity.

Reinforce Progress to Recovery (Elements 9–10)

Help the student to understand that the recovery process is dynamic, and with good activity-exertion management under their control, they will feel better, and the symptoms will decrease. Highlight symptoms that may already be resolving as evidence of progress toward recovery.

As the student improves (i.e., reduced symptoms and greater tolerance for activity), it is important to work constructively with the child and family (and school) to gradually increase the time/ intensity of activity, while continuing to monitor the exertional symptom response. The “sweet spot” of activity-exertion management will be moving closer to their normal schedule and toward the recovery state.

Conclusion

The effective return to school of the student with mTBI is one of the most significant challenges in the recovery process, requiring preparation and careful coordination between the medical systems and the school system. Preparation of both systems can be achieved with existing educational programs and available tools. Key considerations for the medical provider include the individualized definition of the student’s history and symptom profile, following a gradual return to school pathway, knowledge and application of academic accommodations tailored to student’s defined needs, and direct communication with the school mTBI team. Medical guidance of the student’s return to school should take an active, positive, progressive approach to mTBI management with a specific focus on the school challenges faced by the recovering student. To implement an effective, individualized school support program across the span of recovery, the schools must develop a system-wide management program. The program should include the articulation of policies and procedures for student identification and supports, education and training of the school team with defined roles, and implementation of a school-based action plan from initial identification of the student to final recovery. As indicated in the IOM report13, there is a significant need to develop a solid evidence base to better understand the effects of mTBI in the developing child, which will help to refine our efforts to providing effective return to school services for all students.

Table 5.

Concussion Activity-Exertion Management: Progressive Activities of Controlled Exertion (PACE)

| Stage | Treatment Component | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Set the Positive Foundation | 1. Establish a positive, active problem-solving context | Provide the student, family, and school with a psychologically positive, active problem-solving context for rehabilitation. Framing the injury and its recovery in a positive, constructive, reassuring manner is critical. |

| 2. Assess and manage emotional response to injury | Explore the emotional response of the child and family to the injury. Assess how it has disrupted their lives. Ask what stresses or demands they are facing (school, peer, athletics). | |

| 3. Developmentally appropriate education about mTBI and its effects | Provide developmentally appropriate education regarding the dynamics of mTBI (i.e., software injury, energy deficit), and the relationship between the student’s level of activity and symptom exacerbation (exertional effects). Review the sources of exertion: physical, cognitive, emotional – and the need to manage these energy demands. | |

| Define the Parameters of Activity-Exertion | 4a. Define daily schedule 4b. Define type, intensity & duration of cognitive & physical activities and their exertional effects |

a. Define the student’s typical daily schedule (before, during, after school, weekends), b. Define times of the day when activities present the greatest exertional challenges (“hot spots”) and lesser challenges (“cool spots”). Identify the type, intensity and duration of cognitive and physical activities within the daily schedule. |

| 5. Define tolerability for activity intensity and duration | Define limits of tolerability for activity intensity/duration. Identify when symptoms do not increase substantially. This should be done for each key class. Sample question: “How long can you typically go in your classes before you notice your symptoms worsening and affecting your learning?” Use time/intensity limits to schedule “work-rest” breaks. | |

| Teach Activity-Exertion Monitoring Skills | 6. Teach “Not too little, not too much” concept | Teach the concept of moderated activity - engaging in “Not too little, but not too much” activity. The student’s goal is to find the activity “sweet spot” where activity time and effort are maximized without symptoms worsening. |

| 7. Teach “reasonable” symptom monitoring | Teach “reasonable” symptom monitoring and recording. Be aware of child or parent that isoverly anxious or oblivious. Coach them to monitor symptoms reasonably. | |

| 8. Teach working to tolerable limits – using a work-rest-work-rest approach | Instruct the student to work up to their symptom limits, but to not exceed them, by being aware of (i.e., reasonable monitoring) their symptoms. Emphasize tolerance of a mild increase in symptoms, but not excessive increase. | |

| Reinforce Progress | 9. Recovery is dynamic; activity-exertion management will reduce symptoms | Instruct that the recovery process is dynamic, controlled activity-exertion management will feel better, and symptoms will decrease. Highlight examples of resolving symptoms as evidence of progress toward recovery. |

| 10. Gradual increase activity time/intensity. | As symptoms reduced with greater tolerance for activity, gradually increase the time/intensity of activity. The “sweet spot” of activity-exertion will move closer to their norm. |

Acknowledgments

Funding: This paper was supported in part by CDC Awards U17/ CCU323352 and U49CE001385, and NIH Grants # M01RR020359 from the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR), a component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), and NIH # P30/HDO40677-07.

Appendix A

Appendix B

Footnotes

Author contributions: GAG contributed to the concept, writing, and editing of the article.

Declaration of conflicting interests: GAG is a test co-author of the Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Function for which he receives royalties. He is a co-author of the Acute Concussion Evaluation (ACE), ACE Care Plan, ACE Home/School Instructions for which he receives no remuneration.

Ethical approval: The research associated with this article was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Children's National Medical Center (protocol # 00000084)

References

- 1.Sady MD, Vaughan CG, Gioia GA. School and the concussed youth: Recommendations for concussion education and management. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am. 2011;22(4):701–719. doi: 10.1016/j.pmr.2011.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McGrath N. Supporting the student-athlete’s return to the classroom after a sport-related concussion. J Athl Train. 2010;45(5):492–498. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-45.5.492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Centers for Disease Control. [Accessed January 17, 2014];Heads up to schools: Know your concussion ABCs [updated March 23, 2012] Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/concussion/HeadsUp/schools.html.

- 4.Centers for Disease Control. [Accessed January 17, 2014];Returning to School After a Concussion: A Fact Sheet for School Professionals [updated March 23, 2012] Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/concussion/HeadsUp/schools.html.

- 5.Centers for Disease Control. [Accessed January 17, 2014];Helping Students Recovery from a Concussion: Classroom Tips for Teachers [updated March 23, 2012] Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/concussion/HeadsUp/schools.html.

- 6.Halstead ME, McAvoy K, Devore CD, et al. Returning to learning following a concussion. Pediatrics. 2013;132(5):948–957. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-2867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McCrory P, Meeuwisse WH, Johnston K, et al. Consensus statement on concussion in sport - the second international conference on concussion in sport held in Prague, November 2004. Br J Sports Med. 2005;37(2):141–159. [Google Scholar]

- 8.McCrory P, Meeuwisse WH, Johnston K, et al. Consensus statement on concussion in sport - the third international conference on concussion in sport held in Zurich, November 2008. Phys Sportsmed. 2009;37(2):141–159. doi: 10.3810/psm.2009.06.1721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aubry M, Cantu R, Dvorak J, et al. Summary and agreement statement of the First International Conference on Concussion in Sport, Vienna 2001. Recommendations for the improvement of safety and health of athletes who may suffer concussive injuries. Br J Sports Med. 2002;36(1):6–10. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.36.1.6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schneider KJ, Iverson GL, Emery CA, et al. The effects of rest and treatment following sport-related concussion: a systematic review of the literature. Br J Sports Med. 2013;47(5):304–307. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2013-092190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Giza CC, Hovda DA. The Neurometabolic Cascade of Concussion. J Athl Train. 2001;36(3):228–235. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Silverberg ND, Iverson GL, Caplan B, Bogner J. Is rest after concussion ‘the best medicine?’ recommendations for activity aesumption following concussion in athletes, civilians, and military service members. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2013;28(4):250–259. doi: 10.1097/HTR.0b013e31825ad658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Institute of Medicine’s Committee on Sports-Related Concussions in Youth. Sports-Related Concussions in Youth: Improving the Science, Changing the Culture. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Giza CC, Kutcher JS, Ashwal S, et al. Summary of evidence-based guideline update: evaluation and management of concussion in sports: Report of the Guideline Development Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2013;80(24):2250–2257. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31828d57dd. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McCrea MA. Mild traumatic brain injury and postconcussion syndrome: The new evidence base for diagnosis and treatment. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Centers for Disease Control. [Accessed January 17, 2014];Heads up: Brain injury in your practice. 2007 Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/concussion/headsup/physicians_tool_kit.html.

- 17.Gioia G, Collins M, Isquith P. Improving identification and diagnosis of mild traumatic brain injury with evidence: Psychometric support for the acute concussion evaluation. The. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2008;23(4):230–242. doi: 10.1097/01.HTR.0000327255.38881.ca. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gioia GA. Pediatric Assessment and Management of Concussions. Pediatr Ann. 2012;41(5):198–203. doi: 10.3928/00904481-20120426-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guskiewicz KM, Register-Mihalik J, McCrory P, et al. Evidence-based approach to revising the SCAT2: Introducing the SCAT3. Br J Sports Med. 2013;47:289–293. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2013-092225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zuckerbraun N, Atabaki S, Collins M, Thomas D, Gioia G. Use of Modified Acute Concussion Evaluation Tools in the Emergency Department. Pediatrics. 2013;133(4):635–642. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-2600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Oregon Center for Applied Science. Brain 101: The Concussion Playbook. 2007 http://brain101.orcasinc.com/

- 22.McAvoy K. REAP the benefits of good concussion management. Rocky Mountain Youth Sports Medicine Institute; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Leddy J, Willer B. Use of graded exercise testing in concussion and return-to-activity management. Curr Sports Med Rep. 2013;12(6):370–376. doi: 10.1249/JSR.0000000000000008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Leddy JJ, Kozlowski K, Donnelly JP, et al. A preliminary study of subsymptom threshold exercise training for refractory post-concussion syndrome. Clin J Sports Med. 2010;20(1):21–27. doi: 10.1097/JSM.0b013e3181c6c22c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Griesbach GS. Exercise after traumatic brain injury: is it a double-edged sword? PMR. 2011;3(6 Suppl 1):S64–S72. doi: 10.1016/j.pmrj.2011.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gioia GA, Vaughan CG, Reesman JH, et al. Characterizing post-concussion exertional effects in the child and adolescent. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2010;16(S1):178. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Aylward BS, Bender JA, Graves MM, Roberts MC. Historical developments and trends in pediatric psychology. In: Roberts MC, Steele RG, editors. Handbook of Pediatric Psychology. 4th Edition. New York: Guilford Press; 2009. pp. 3–18. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Majerske CW, Mihalik JP, Ren D, Collins MW, Reddy CC, Lovell MR, Wagner AK. Concussion in sports: postconcussive activity levels, symptoms, and neurocognitive performance. J Athl Train. 2008;43(3):265–274. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-43.3.265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]