Abstract

Purpose:

Beam’s-eye-view (BEV) imaging with an electronic portal imaging device (EPID) can be performed during lung stereotactic body radiation therapy (SBRT) to monitor the tumor location in real-time. Image quality for each patient and treatment field depends on several factors including the patient anatomy and the gantry and couch angles. The authors investigated the angular dependence of automatic tumor localization during non-coplanar lung SBRT delivery.

Methods:

All images were acquired at a frame rate of 12 Hz with an amorphous silicon EPID. A previously validated markerless lung tumor localization algorithm was employed with manual localization as the reference. From ten SBRT patients, 12 987 image frames of 123 image sequences acquired at 48 different gantry–couch rotations were analyzed. δ was defined by the position difference of the automatic and manual localization.

Results:

Regardless of the couch angle, the best tracking performance was found in image sequences with a gantry angle within 20° of 250° (δ = 1.40 mm). Image sequences acquired with gantry angles of 150°, 210°, and 350° also led to good tracking performances with δ = 1.77–2.00 mm. Overall, the couch angle was not correlated with the tracking results. Among all the gantry–couch combinations, image sequences acquired at (θ = 30°, ϕ = 330°), (θ = 210°, ϕ = 10°), and (θ = 250°, ϕ = 30°) led to the best tracking results with δ = 1.19–1.82 mm. The worst performing combinations were (θ = 90° and 230°, ϕ = 10°) and (θ = 270°, ϕ = 30°) with δ > 3.5 mm. However, 35% (17/48) of the gantry–couch rotations demonstrated substantial variability in tracking performances between patients. For example, the field angle (θ = 70°, ϕ = 10°) was acquired for five patients. While the tracking errors were ≤1.98 mm for three patients, poor performance was found for the other two patients with δ ≥ 2.18 mm, leading to average tracking error of 2.70 mm. Only one image sequence was acquired for all other gantry–couch rotations (δ = 1.18–10.29 mm).

Conclusions:

Non-coplanar beams with gantry–couch rotation of (θ = 30°, ϕ = 330°), (θ = 210°, ϕ = 10°), and (θ = 250°, ϕ = 30°) have the highest accuracy for BEV lung tumor localization. Additionally, gantry angles of 150°, 210°, 250°, and 350° also offer good tracking performance. The beam geometries (θ = 90° and 230°, ϕ = 10°) and (θ = 270°, ϕ = 30°) are associated with substantial automatic localization errors. Overall, lung tumor visibility and tracking performance were patient dependent for a substantial number of the gantry–couch angle combinations studied.

Keywords: stereotactic body radiation therapy, non-coplanar radiotherapy, markerless tracking, beam’s-eye-view imaging, EPID imaging

1. INTRODUCTION

Stereotactic body radiation therapy (SBRT) is a promising alternative to surgery for patients with localized nonsmall cell lung cancer.1–4 To achieve accurate tumor coverage and critical structure avoidance, SBRT treatment plans often consist of multiple beam angle arrangements.5–10 Recently, studies have shown that combining gantry and couch rotations in non-coplanar beam arrangements can improve dose conformity over coplanar beams only.7,11,12 Despite the improvement, changes in patient breathing patterns can cause lung tumors to move out of the irradiation field.13,14 Therefore, it is important to continuously monitor tumor movement during treatment for coplanar and non-coplanar beam geometries.

An electronic portal imaging device (EPID) can be implemented to monitor tumor location from the treatment beam’s-eye-view (BEV) without introducing additional radiation dose to patients.15–17 Rottmann et al. developed a robust tracking algorithm that estimates tumor location based on automatically detected landmarks from sequential EPID frames.17 The autolocalization of tumor positions resulting from the algorithm has shown great potential in real time multileaf collimator treatment aperture adaptation,18 monitoring relative position of physician-defined gross tumor volume and treatment field19 and estimating delivered dose.20

Since EPID images capture the exit fluence of the treatment beam, their quality for tracking purposes depends on the traversed patient anatomy and thus the combination of gantry and couch angles.21 Therefore, identification of gantry–couch rotations that are associated with reliable autotracking performance can be important for real time treatment monitoring. In this study, we investigated the relationship between gantry–couch rotation and autotracking errors in 123 BEV image sequences.

2. METHODS AND MATERIALS

2.A. Image acquisition

The treatment delivery of ten randomly selected SBRT patients with nonsmall cell lung cancer was monitored with BEV EPID imaging in cine-mode. Radiation dose was delivered from 6 to 12 coplanar and non-coplanar beams. All images were acquired with a 6 MV beam at a frame rate of 12 Hz with an AS1000 portal imager mounted on the gantry of a Varian TX clinical linear accelerator (Varian Medical Systems, Palo Alto, CA). The resolution of the images was 512 × 384 pixels. Each cine-EPID movie (67–221 frames/movie) is hereafter referred to as an image sequence. A total of 123 image sequences with a combined 12 987 frames were acquired.

2.B. Autotracking algorithm and manual tracking

A markerless tracking algorithm for soft-tissue localization (STiL) (Ref. 17) was employed to perform autotracking on all 123 image sequences. This algorithm is described in detail in previous publications.17,18

In addition to the autotracking, manual soft-tissue tracking was also performed on each image sequence. A region-of-interest (ROI) including the tumor was manually chosen in the first frame. The corresponding ROI on all other frames of the same image sequence was then identified by an expert observer (S.Y.) who has two years of experience identifying tumors on in-treatment EPID images. The geometric difference () between the corresponding ROI therefore determined the movement of the target. Each frame was analyzed three times and the order of the presented frames was randomized in order to reduce intraobserver variability and to avoid possible bias, respectively.17,18 A total of 38 961 (12 987 × 3) frames were manually tracked. The average of for three separate tracks was taken as the tumor reference location. The error of automatic tracking for each image sequence was then defined as

| (1) |

where N is the number of frames per image sequence.

Suh et al. found that the error for 2D projection along the imaging beam axis of 3D tumor motion is nearly 2 mm.22 Moreover, in the validation study of STiL, we found the average tracking error for the patient data to be 2 mm.17 We therefore adopted the criterion that the tracking performance with error (δ) ≤ 2 mm was considered to be good. Particularly, tracking error between 2 and 3 mm was considered to be fair tracking performance, while tracking errors >3 mm were considered to be poor performance.

2.C. Image sequence visibility

The quality of tumor visibility in each image sequence was classified as poor, fair, and good according to visual inspection of the expert observer. An image sequence was considered to have good visibility if strong features could be clearly identified on all frames for manual tracking (e.g., patient 1 in Fig. 3). Poor visibility indicates that no feature can be visually identified (e.g., patient 10 in Fig. 3). Fair visibility was assigned to those sequences for which features could sometime be identified for tracking; however, they may become obscured by surrounding tissues with similar intensity on some of the frames [e.g., image sequence acquired at (θ = 90°, ϕ = 25°) in Fig. 5].

FIG. 3.

Examples of good (patient 1) and poor (patient 10) tracking performance. The red arrow in patient 1 indicates strong feature that can be identified for tracking. Both tumors are located in the right lower lobe.

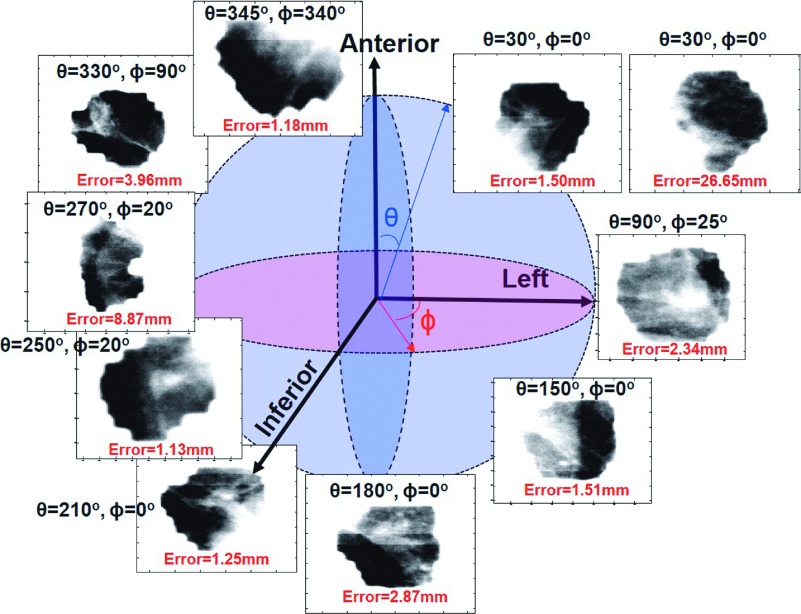

FIG. 5.

Ten example image sequences acquired at different gantry (θ) and couch (ϕ) angles. IEC 61217 Varian coordinate system was used in this study. Particularly, the gantry (θ) and couch (ϕ) angles increase in the clockwise rotation from the therapists’ perspective.

We investigated the impact of the subjective visibility on tracking error by assessing their correlation using Pearson’s correlation coefficient (R). The correlation was considered to be significant if p < 0.05.

2.D. Data analysis

2.D.1. Interpatient variability

To study the variability in tracking performance between patients, the tracking errors for each patient were averaged over all each patient’s image sequences, respectively. ANOVA test was performed to investigate if the tracking error in at least one patient was significantly different (p < 0.05) from another.

2.D.2. Gantry–couch angle dependence

For all patients, there were 38, 11, and 65 unique gantry angles (θ), couch angles (ϕ), and gantry–couch angle combinations, respectively. Similar angles were grouped such that image sequences acquired at the angles θ − 10° ≤ θ < θ + 10° and ϕ − 10° ≤ ϕ < ϕ + 10° were analyzed together. For example, (θ = 190°, ϕ = 10°) included image sequences acquired at 180° ≤ θ < 200° and 0° ≤ ϕ < 20°. For each gantry–couch angle combination (θ,ϕ), the tracking errors were averaged over all the image sequences acquired at the angles θ − 10° ≤ θ < θ + 10° and ϕ − 10° ≤ ϕ < ϕ + 10°.

2.D.3. Tumor location dependence

The patient cohort included tumors located in the left upper lobe, left lower lobe, right upper lobe, and right lower lobe, respectively. The tracking errors of all 123 imaging sequences (12 987 frames) resulting from different tumor locations were compared using ANOVA test to determine whether tumors located in a particular location led to significantly (p < 0.05) better tracking performance.

BEV image quality can be degraded by background signals in the treatment aperture due to spine and organs near the mediastinum wall (e.g., esophagus, heart, and bronchi) leading to poor tumor tracking. We categorized all imaging sequences into those that were acquired with and without beams passing through these organs. The tracking error between these two categories was compared using t-test (p < 0.05) to assess if the presence of these organs in the treatment aperture (BEV) significantly reduced tracking performance.

2.D.4. Relationship between intraobserver variability and autotracking error

As each frame was manually analyzed three times, intraobserver variability was quantified by the standard deviation of these manual tracks . The relationship between and tracking error was assessed using Pearson’s correlation coefficient.

3. RESULTS

3.A. EPID image visibility and interpatient variability

Figure 1 shows that the visibility of EPID images was strongly correlated to the accuracy of tracking with R = − 0.59 (p ∼ 10−13). Of 123 image sequences, 60 (49%), 42 (34%), and 21 (17%) were identified to have poor, fair, and good visibility, respectively. The average tracking error for the image sequences with poor, fair, and good visibility was 5.58, 2.10, and 1.75 mm, respectively.

FIG. 1.

Relationship between subjective visibility and tracking error. The horizontal line and square inside each boxplot represent median and average tracking error, respectively.

Significant interpatient variability (p = 0.01) in tracking performance was observed (Fig. 2). In particular, the average tracking errors ranged from 1.58 to 7.68 mm between all ten patients. Figure 3 shows two example patients, both with tumors located in the right lower lobe. An image sequence of patient 1 acquired at the gantry (θ) and couch (ϕ) angles of 250° and 20°, respectively, demonstrated excellent visibility with tracking error of only 1.31 mm (Fig. 3). However, the visibility of image sequence for patient 10 acquired at (θ = 270°, ϕ = 20°) was poor with tracking error of 8.87 mm.

FIG. 2.

Interpatient variability. The horizontal line and square inside each boxplot represent median and average tracking error, respectively.

3.B. Gantry (θ) and couch (ϕ) angle dependence

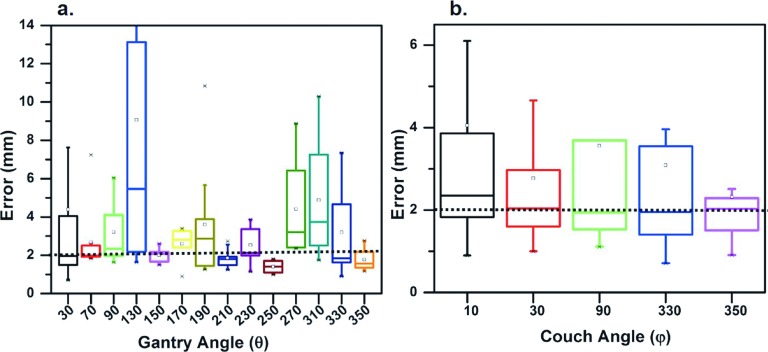

As observed in Fig. 4(a), the best tracking performance was found in image sequences with gantry angle of 250° (±10°) (average δ = 1.40 mm). Image sequences acquired with gantry angles of 150°, 210°, and 350° also led to good tracking performances with average δ = 1.77–2.00 mm [Fig. 4(a)]. Inconsistent tracking performances were found in all other gantry angles with average tracking errors between 2.29 and 9.06 mm. For example, while couch angles were identical (ϕ = 20°) for patients 1 and 10 in Fig. 3, the tracking error for the image sequence of patient 1 acquired at gantry angle of 250° was substantially less than the image sequence of patient 10 acquired at the gantry angle of 270° (as described above). Overall, couch angle was not significantly correlated with tracking error.

FIG. 4.

(a) Tracking error and gantry angle. (b) Tracking error and couch angle. The horizontal line and square inside each boxplot represent median and average tracking error, respectively.

After grouping, there were a total of 49 gantry–couch angle combinations. However, only one image sequence was acquired for 52% (25/48) of the gantry–couch angle combinations. Of these, the gantry–couch rotations of (θ = 30°, 90°, and 350°, ϕ = 350°), (θ = 110° and 230°, ϕ = 30°), (θ = 190°, ϕ = 70°), (θ = 210°, ϕ = 290° and 350°), (θ = 250°, ϕ = 350°), and (θ = 350°, ϕ = 90° and 350°) were found to have good performance with δ = 1.16–1.99 mm. Fair tracking performances were found in (θ = 50°, ϕ = 10° and 30°), (θ = 70°, ϕ = 30° and 350°), (θ = 110°, ϕ = 10° and 350°), (θ = 210°, ϕ = 30°), (θ = 270°, ϕ = 10°), (θ = 330°, ϕ = 50°), and (θ = 130°, 230°, and 290°, ϕ = 350°) with δ = 2.06–2.93 mm. Poor performances were found in (θ = 270°, ϕ = 350°) and (θ = 310°, ϕ = 10° and 310°) with δ ⩾ 3.27 mm.

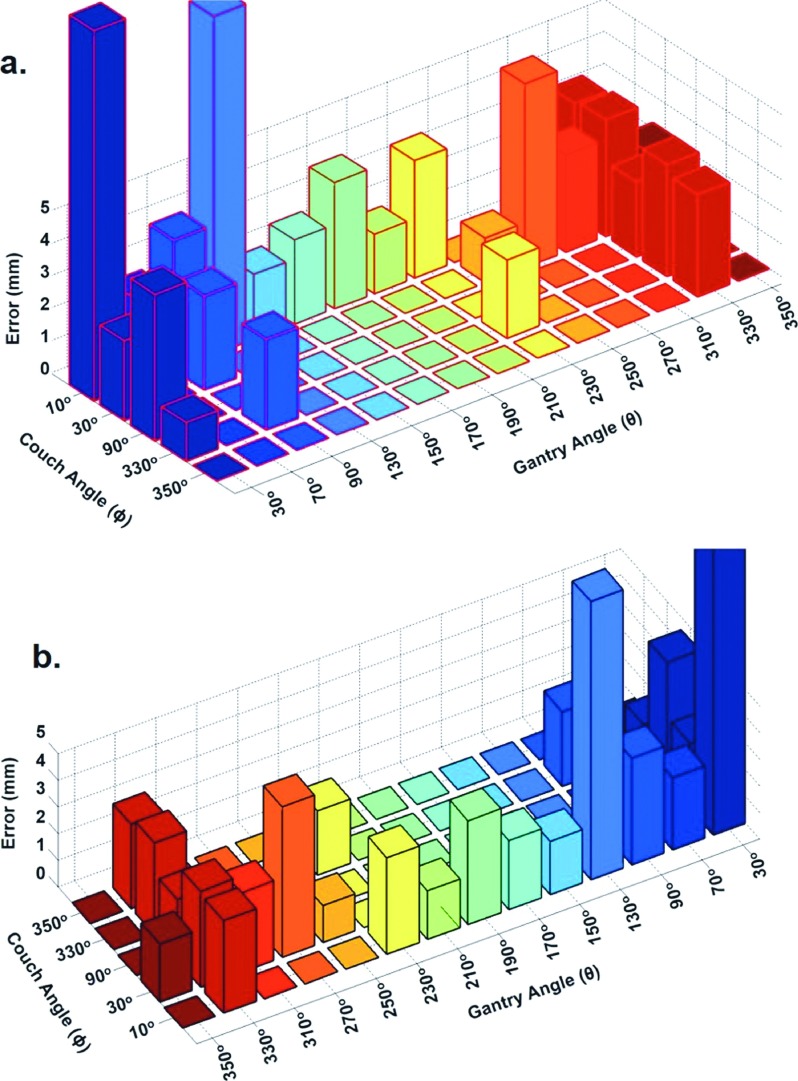

Figure 5 shows examples of EPID image sequences acquired at ten different gantry–couch angle combinations and their tracking errors. Figure 6 only shows the 3D bar plots of average tracking errors for 23 combinations with at least three image sequences. The most accurately tracked image sequences were acquired at (θ = 30°, ϕ = 330°), (θ = 210°, ϕ = 10°), and (θ = 250°, ϕ = 30°) for two, five, and two patients, respectively. The autotracking performances for these image sequences were found to be good with average tracking errors ranging from 1.19 to 1.82 mm (Fig. 6).

FIG. 6.

Gantry (θ) and couch (ϕ) angle dependence of the tracking performance. Each bar indicates average tracking error on an image sequence acquired at a specific (θ, ϕ) combination. Figures 6(a) and 6(b) are the same bar plot displayed in two different orientations for easy visualization.

Seventeen gantry–couch angle combinations including (θ = 30°, ϕ = 10°, 30°, and 90°), (θ = 70°, 130°, 150°, 170°, and 190°, ϕ = 10°), (θ = 90°, ϕ = 30° and 330°), (θ = 310° and 350°, ϕ = 30°), (θ = 330°, ϕ = 10°, 30°, 90°, 330°, and 350°), and (θ = 350°, ϕ = 30°) demonstrated substantial variability in tracking performances between patients. For example, an image sequence acquired at (θ = 30°, ϕ = 10°) was obtained for three patients (Fig. 5). While the tracking performance was found to be good in one patient with error of only 1.50 mm, the tracking performances were poor in the other two patients (δ > 6 mm), leading to an average error of 11.42 mm. Image sequences were acquired at (θ = 70°, ϕ = 10°) for five patients. While the tracking errors were ≤1.98 mm for three patients, errors were found to be δ = 2.18 and 7.24 mm for the other two patients, leading to only fair tracking performance with δ = 2.70 mm. The average tracking errors ranged from 2.18 to 11.42 mm in these seventeen gantry–couch angle combinations.

Gantry–couch rotations (θ = 90° and 230°, ϕ = 10°) and (θ = 270°, ϕ = 30°) led to poor tracking performances for all image sequences with average errors were 3.62 and 5.66 mm, respectively.

3.C. Tumor location dependence

ANOVA test showed that tumors located in the left upper lobe led to significantly better autotracking performance (p = 0.04). In particular, the average tracking error for tumors in the left upper lobe, left lower lobe, right upper lobe, and right lower lobe was 2.40, 6.13, 3.45, and 3.72 mm, respectively.

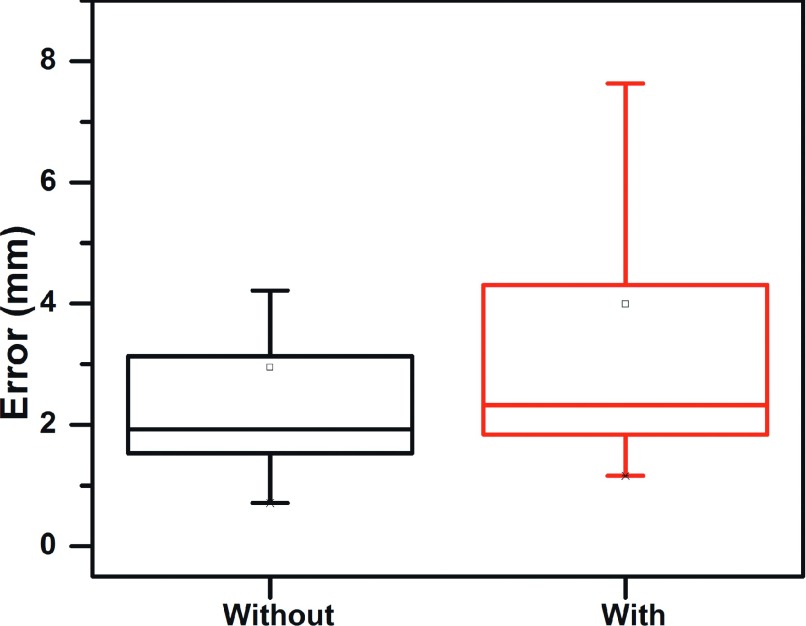

The tracking errors of images acquired from treatment beams that pass through various organs ranged from 1.16 to 26.5 mm (average error = 3.99 mm). The range for those beams that did not traverse these organs was 0.71 to 26.7 mm (average error: 2.95 mm). These results are shown in Fig. 7 and the t-test demonstrated an insignificant difference (p = 0.15).

FIG. 7.

Tracking error of images acquired with and without obstructing organs (e.g., spine, heart, and esophagus) within the treatment aperture.

3.D. Relationship between intraobserver variability and autotracking error

The average intraobserver variability was 1.5 mm (range: 0.65–7.41 mm). Tracking error and variations among three separate manual tracks were moderately correlated with R = 0.60 (p ∼ 10−13), suggesting that images with high intraobserver variability can lead to poor tracking performance.

4. DISCUSSION

EPID images capture the exit fluence of the treatment beam and the projection of patient’s traversed anatomy. Therefore, the quality of EPID images for autotracking depends on the combination of gantry and couch rotations. This study investigated the relationship between gantry–couch rotations and autotracking error.

In this study, we found that the gantry–couch angles of (θ = 30°, ϕ = 330°), (θ = 210°, ϕ = 10°), and (θ = 250°, ϕ = 30°) were associated with accurate automatic tracking of lung tumors (δ ≤ 1.82 mm) (Fig. 6). Although these beam geometries may provide the best tumor visibility, they may not be feasible for all lung SBRT patients. A number of factors, including target dose conformity, avoidance of critical organs, gantry–couch collision, and patient–gantry collisions, need to be considered in choosing the beam geometry or direction.23 For example, the (θ = 210°, ϕ = 10°) beam angle was applied in 50% (5/10) of the patients studied, while the (θ = 30°, ϕ = 330°) and (θ = 250°, ϕ = 30°) angles were only used in 20% (2/10) of the patients. This observation may suggest that these beam geometries may not provide an appropriate dose conformity for the other patients. This hypothesis will be investigated in the future studies.

Gantry angles of 150°, 210°, 250°, and 350° also provided accurate lung tumor localization (δ < 2.0 mm), regardless of the couch angles. Moreover, these gantry angles were used all but one (patient 10) of the plans for the patients studied. This may partially explain the overall poor tracking performance (δ = 5.86 mm) in patient 10 (Figs. 2 and 3). By contrast, the tracking error averaged over all beam angles for patient 1 was only 1.56 mm. For patient 1, 63% (5/8) of the beam geometries included gantry angles of 150°, 210°, 250°, and 350°.

In general, increasing the number of non-coplanar beams can improve overall conformity of dose distribution for a SBRT treatment plan.23 However, studies have investigated the impact of the number of coplanar and non-coplanar beam arrangements on dose distributions in lung SBRT.5,6 It has been found that using more than ten beams had no significant improvement in dose conformity. The gantry–couch angle combinations (θ = 90° and 230° ϕ = 10°) that led to substantial tracking error (δ > 3.5 mm) were found in patients 4 and 7. Eleven and twelve coplanar and non-coplanar beams were used in these two patients, respectively. More accurate real-time tumor localization could be enabled by the exclusion of these beam angles (θ = 90° and 230° ϕ = 10°). However, care should be taken to ensure that there is no degradation in the treatment plan quality.

The automatic localization in a substantial number of the gantry–couch angle combinations may be patient specific. The gantry–couch angle combinations of 35% (17/48) studied led to neither consistently poor nor consistently good tracking performance. One example is the image sequences acquired at (θ = 70°, ϕ = 10°) for five of the patients. In these image sequences, the tracking performance was found to be good for three patients. However, fair to poor performances were found for the other two patients with error of 2.18 and 7.24 mm, respectively. These results suggest that factors other than beam geometry, such as tumor location, may also influence autotracking quality.

Tumor locations may also be associated with tumor motion magnitude, subsequently influencing the quality of EPID images for the purpose of autotracking. Although the autotracking performances were found to be fair to poor for some image sequences for all locations, the tumors located in lower lobes exhibited significantly smaller tracking error (p = 0.04). This may be due, in part, to the relative volume of lung tissue surrounding the lower lobe tumors, providing greater contrast in the BEV images.

The visibility of lung tumors in BEV images can significantly influence the autotracking performance. In particular, the correlation between the visibility and tracking error was −0.59 with p ≪ 0.01. Richter et al. investigated the lung tumor visibility on 668 EPID image sequences and found that the tumor was visible in 47% of the image sequences.24 Contrary to our study, Richter et al. did not show that their visibility measures are related to tracking errors, although they employed a different tracking algorithm. Even with our tracking algorithm, tumors without strong visible features can exhibit poor tracking performance. For example, as observed in Fig. 6, the tumor can be clearly captured on an EPID frame acquired from (θ = 90°, ϕ = 25°). However, since the tumor was surrounded by soft-tissue, it appears to “blend” into the background in some frames, leading to a fair tracking result (δ = 2.34 mm). Improvements in EPID detector technology could provide improved contrast for these borderline tumors, increasing the proportion of image sequences in which lung tumors can be accurately tracked.

In this study, we identified some of gantry–couch rotations that can lead to good (or poor) automatic tumor localization. However, for 52% (25/48) of the non-coplanar treatment beam geometries, only one image sequence was acquired. It is inconclusive that if these beam geometries can consistently provide beam’s-eye-view images for accurate tracking. For example, although an image sequence acquired at the gantry–couch rotation of (θ = 345°, ϕ = 340°) appears to have poor visibility, its tracking error was only 1.18 mm (Fig. 5). Since only one image sequence was acquired at (θ = 345°, ϕ = 340°), it was unclear if the good tracking performance was patient dependent. Therefore, more image sequences need to be acquired for these gantry–couch geometries to further investigate if they can provide accurate tracking.

5. CONCLUSION

Non-coplanar treatment beams with gantry–couch rotation of (θ = 30°, ϕ = 330°), (θ = 210°, ϕ = 10°), and (θ = 250°, ϕ = 30°) provide BEV images for which the most accurate tracking is likely to occur. Gantry angles of 150°, 210°, 250°, and 350° also provide accurate tracking in most cases. Beam geometries including (θ = 90° and 230°, ϕ = 10°) and (θ = 270°, ϕ = 30°) may not be appropriate for BEV lung tumor tracking as they can lead to substantial tracking error (δ > 3.5 mm). More accurate real-time tumor localization could be enabled by the exclusion of these beam angles (θ = 90° and 230° ϕ = 10°). However, care should be taken to ensure that there is no degradation in the treatment plan quality.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The project described was supported, in part, by a grant from Varian Medical Systems, Inc., and Award No. R01CA188446-01 from the National Cancer Institute. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Cancer Institute or the National Institutes of Health.

REFERENCES

- 1.Nagata Y., Takayama K., Matsuo Y., Norihisa Y., Mizowaki T., Sakamoto T., Sakamoto M., Mitsumori M., Shibuya K., Araki N., Yano S., and Hiraoka M., “Clinical outcomes of a phase I/II study of 48 Gy of stereotactic body radiotherapy in 4 fractions for primary lung cancer using a stereotactic body frame,” Int. J. Radiat. Oncol., Biol., Phys. 63, 1427–1431 (2005). 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2005.05.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Onishi H., Shirato H., Nagata Y., Hiraoka M., Fujino M., Gomi K., Karasawa K., Hayakawa K., Niibe Y., Takai Y., Kimura T., Takeda A., Ouchi A., Hareyama M., Kokubo M., Kozuka T., Arimoto T., Hara R., Itami J., and Araki T., “Stereotactic body radiotherapy (SBRT) for operable stage I non-small-cell lung cancer: Can SBRT be comparable to surgery?,” Int. J. Radiat. Oncol., Biol., Phys. 81, 1352–1358 (2011). 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2009.07.1751 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fakiris A. J., Mcgarry R. C., Yiannoutsos C. T., Papiez L., Williams M., Henderson M. A., and Timmerman R., “Stereotactic body radiation therapy for early-stage non-small-cell lung carcinoma: Four-year results of a prospective phase II study,” Int. J. Radiat. Oncol., Biol., Phys. 75, 677–682 (2009). 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2008.11.042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mcgarry R. C., Papiez L., Williams M., Whitford T., and Timmerman R. D., “Stereotactic body radiation therapy of early-stage non-small-cell lung carcinoma: Phase I study,” Int. J. Radiat. Oncol., Biol., Phys. 63, 1010–1015 (2005). 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2005.03.073 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Takayama K., Nagata Y., Negoro Y., Mizowaki T., Sakamoto T., Sakamoto M., Aoki T., Yano S., Koga S., and Hiraoka M., “Treatment planning of stereotactic radiotherapy for solitary lung tumor,” Int. J. Radiat. Oncol., Biol., Phys. 61, 1565–1571 (2005). 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2004.12.066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liu R., Buatti J. M., Howes T. L., Dill J., Modrick J. M., and Meeks S. L., “Optimal number of beams for stereotactic body radiotherapy of lung and liver lesions,” Int. J. Radiat. Oncol., Biol., Phys. 66, 906–912 (2006). 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2006.05.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lim D. H., Yi B. Y., Mirmiran A., Dhople A., Suntharalingam M., and D’souza W. D., “Optimal beam arrangement for stereotactic body radiation therapy delivery in lung tumors,” Acta Oncol. 49, 219–224 (2010). 10.3109/02841860903302897 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fukumoto S.-i., Shirato H., Shimzu S., Ogura S., Onimaru R., Kitamura K., Yamazaki K., Miyasaka K., Nishimura M., and Dosaka-Akita H., “Small-volume image-guided radiotherapy using hypofractionated, coplanar, and noncoplanar multiple fields for patients with inoperable stage I nonsmall cell lung carcinomas,” Cancer 95, 1546–1553 (2002). 10.1002/cncr.10853 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hof H., Herfarth K. K., Münter M., Hoess A., Motsch J., Wannenmacher M., and ü Debus J., “Stereotactic single-dose radiotherapy of stage I non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC),” Int. J. Radiat. Oncol., Biol., Phys. 56, 335–341 (2003). 10.1016/S0360-3016(02)04504-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wulf J., Haedinger U., Oppitz U., Thiele W., Mueller G., and Flentje M., “Stereotactic radiotherapy for primary lung cancer and pulmonary metastases: A noninvasive treatment approach in medically inoperable patients,” Int. J. Radiat. Oncol., Biol., Phys. 60, 186–196 (2004). 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2004.02.060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dong P., Lee P., Ruan D., Long T., Romeijn E., Low D. A., Kupelian P., Abraham J., Yang Y., and Sheng K., “4π noncoplanar stereotactic body radiation therapy for centrally located or larger lung tumors,” Int. J. Radiat. Oncol., Biol., Phys. 86, 407–413 (2013). 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2013.02.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Xiaodong Z., Xiaoqiang L., Enzhuo M. Q., Xiaoning P., and Yupeng L., “A methodology for automatic intensity-modulated radiation treatment planning for lung cancer,” Phys. Med. Biol. 56, 3873–3893 (2011). 10.1088/0031-9155/56/13/009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jiang S. B., “Radiotherapy of mobile tumors,” Semin. Radiat. Oncol. 16, 239–248 (2006). 10.1016/j.semradonc.2006.04.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Keall P. J., Mageras G. S., Balter J. M., Emery R. S., Forster K. M., Jiang S. B., Kapatoes J. M., Low D. A., Murphy M. J., Murray B. R., Ramsey C. R., Van Herk M. B., Vedam S. S., Wong J. W., and Yorke E., “The management of respiratory motion in radiation oncology report of AAPM Task Group 76,” Med. Phys. 33, 3874–3900 (2006). 10.1118/1.2349696 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Berbeco R. I., Hacker F., Ionascu D., and Mamon H. J., “Clinical feasibility of using an EPID in cine mode for image-guided verification of stereotactic body radiotherapy,” Int. J. Radiat. Oncol., Biol., Phys. 69, 258–266 (2007). 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2007.04.051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Park S.-J., Ionascu D., Hacker F., Mamon H., and Berbeco R., “Automatic marker detection and 3D position reconstruction using cine EPID images for SBRT verification,” Med. Phys. 36, 4536–4546 (2009). 10.1118/1.3218845 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rottmann J., Aristophanous M., Chen A., Court L., and Berbeco R., “A multi-region algorithm for markerless beam’s-eye view lung tumor tracking,” Phys. Med. Biol. 55, 5585–5598 (2010). 10.1088/0031-9155/55/18/021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rottmann J., Keall P., and Berbeco R., “Real-time soft tissue motion estimation for lung tumors during radiotherapy delivery,” Med. Phys. 40(9), 091713 (10pp.) (2013). 10.1118/1.4818655 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bryant J. H., Rottmann J., Lewis J. H., Mishra P., Keall P. J., and Berbeco R. I., “Registration of clinical volumes to beams-eye-view images for real-time tracking,” Med. Phys. 41, 121703 (9pp.) (2014). 10.1118/1.4900603 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Aristophanous M., Rottmann J., Court L. E., and Berbeco R. I., “EPID-guided 3D dose verification of lung SBRT,” Med. Phys. 38, 495–503 (2011). 10.1118/1.3532821 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mao W., Hsu A., Riaz N., Lee L., Wiersma R., Luxton G., King C., Xing L., and Solberg T., “Image-guided radiotherapy in near real time with intensity-modulated radiotherapy megavoltage treatment beam imaging,” Int. J. Radiat. Oncol., Biol., Phys. 75, 603–610 (2009). 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2009.04.068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Suh Y., Dieterich S., and Keall P. J., “Geometric uncertainty of 2D projection imaging in monitoring 3D tumor motion,” Phys. Med. Biol. 52, 3439–3454 (2007). 10.1088/0031-9155/52/12/008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Benedict S. H., Yenice K. M., Followill D., Galvin J. M., Hinson W., Kavanagh B., Keall P., Lovelock M., Meeks S., Papiez L., Purdie T., Sadagopan R., Schell M. C., Salter B., Schlesinger D. J., Shiu A. S., Solberg T., Song D. Y., Stieber V., Timmerman R., Tomé W. A., Verellen D., Wang L., and Yin F.-F., “Stereotactic body radiation therapy: The report of AAPM Task Group 101,” Med. Phys. 37, 4078–4101 (2010). 10.1118/1.3438081 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Richter A., Wilbert J., Baier K., Flentje M., and Guckenberger M., “Feasibility study for markerless tracking of lung tumors in stereotactic body radiotherapy,” Int. J. Radiat. Oncol., Biol., Phys. 78, 618–627 (2010). 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2009.11.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]