Abstract

Objectives

Summarize hepatitis C virus (HCV) prevalence in injecting (IDU) and non-injecting drug users (NIDU), men who have sex with men (MSM), sex workers, and prison inmates in Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC).

Methods

Systematic review on HCV prevalence in sub-populations in LAC. Databases searched from 1-1-2000 to 10-30-2013. Inclusion criteria: prevalence studies in sub-populations in LAC. HCV-antibody was marker for prevalence of current/past HCV infection and HCV-RNA for prevalence of HCV current infection.

Results

IDU HCV current/past infection presented highest prevalence, from 1.7 % in Colombia to over 95 % in Ciudad Juarez and Tijuana, Mexico and pooled regional anti-HCV prevalence was 49 % (CI 95 % 22.6–76.3 %). NIDU, MSM and sex workers anti-HCV prevalence was below 10 %, and pooled regional prevalence of 4 % (CI 95 % 2.6–4.5 %), 3 % (CI 95 % 1.7–4.5 %) and 2 % (CI 95 % 1.0–3.4 %), respectively. Prison inmates presented higher values, but prevalence decreased over the 15-year time span (p < 0.001). Current HCV infection from three countries showed prevalence under 10 % in prison inmates and 1–46 % among drug users.

Conclusions

Disease burden is high and surveillance, prevention and treatment should target these groups in LAC.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s00038-015-0708-5) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Hepatitis C, Latin America, Caribbean, Drug users, Men who have sex with men, Prisoners

Introduction

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection is a leading cause of chronic liver disease, cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma (Perz et al. 2006). Hepatitis C causes chronic infection in almost 3 % of the world population and, since its discovery in 1989, has emerged as a worldwide public health concern (WHO 2010). Recent estimates for Central, South America and the Caribbean indicate HCV population prevalence levels between 1.5 and 3.5 % (Mohd Hanafiah et al. 2013). Furthermore, Brazil and Mexico together may have 4 million people with HCV (Szabo et al. 2012). The burden of HCV varies geographically and among subpopulations (Szabo et al. 2012; Kershenobich et al. 2011; Lavanchy 2011). Several studies from Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC) have reported a high prevalence among injecting drug users (Weissenbacher et al. 2003) and prison inmates (Guimaraes et al. 2001) as well as in other vulnerable populations, such as sex workers (Pando et al. 2006a, b), and men who have sex with men (MSM) (Pando et al. 2012). No systematic review has been conducted on HCV infection prevalence among specific population groups in LAC. To effectively respond to viral hepatitis C through provision of appropriate treatment and care services, it is critical to document a disproportionate impact and burden of disease among different population groups in LAC. This study aims to summarize available information on prevalence of hepatitis C infection in drug users, injecting and non-injecting, MSM, sex workers, male to female transgender populations and prison inmates in LAC.

Methods

A systematic review and meta-analysis on hepatitis C prevalence in different population groups in LAC was conducted according to the PRISMA statement (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) (Moher et al. 2009). Search terms (all fields) for the PubMed, LILACS and SciELO databases were: “hepatitis OR HAV OR HBV OR HCV OR HDV OR HEV” and “prevalence OR epidemiology” and, for the PubMed search only, a combination of the names of regions, countries and big cities in LAC (Electronic Supplemental Material, Table 1 presents the search terms used for the review). Searches included original articles in English, Spanish, French or Portuguese. We also screened the references of retrieved articles. One reviewer screened all abstracts and full texts for the inclusion criteria and conducted the data extraction. A second expert conducted data extraction on a random sample of studies.

The inclusion criteria consisted of the following: primary sources published between 01/01/2000 and 10/01/2013 with data on Hepatitis C prevalence in one or more of the following populations from LAC countries: Sex workers, MSM, transgender populations, prison inmates and drug users. We defined key populations as both most-at-risk populations and vulnerable populations according to the 2013 WHO classification for HIV (WHO 2013a, b). If several publications were based on the same study, only one of the publications was included. Exclusion criteria were studies with a sample size <75 and studies that did not mention the testing markers. The sample size cutoff criteria (75 participants or greater) were decided given the paucity of studies in the region.

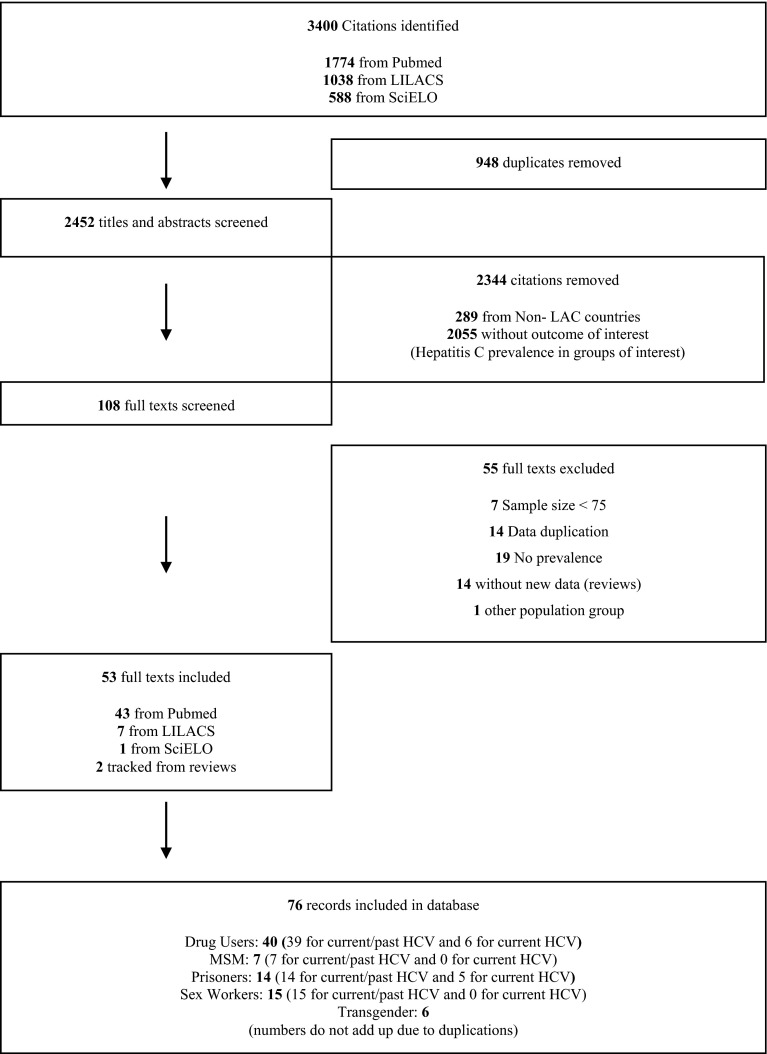

The flow chart of the systematic review and meta-analysis is shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram of the study selection procedure for the review on prevalence of current and/or past Hepatitis C infection in Latin America and the Caribbean from 2000 to 2013

Positivity to anti-HCV antibody was interpreted as current and/or past infection (current/past). HCV-RNA positivity was categorized as current infection. For HCV-RNA, prevalence was given as percentage of the whole study sample although testing was sometimes only done among anti-HCV positive individuals. Whenever possible, prevalence from confirmatory tests was used. Wilson confidence intervals were calculated for each prevalence point.

The quality of the included studies in the review was evaluated with the QATSO scale developed by Wong et col. (Wong et al. 2008). Two additional criteria were evaluated: the acceptability of the case definition for each subpopulation and for the outcome variable and the adequacy of the sample size.

Data extraction

HCV prevalence was extracted from the studies based on hepatitis C marker (antibody or RNA) and by population group. Multiple center studies were split up into sites/cities when possible. Therefore, one reference could yield multiple records. Additional characteristics collected were gender, age group, genotype, data collection period, study setting, country and city or area, sample size, and type of laboratory test.

Statistical analysis

Linear and multiple regression analysis evaluated the influence of year of field work on prevalence, using R statistical language and environment (R Core Team 2011). The analysis was applied within population groups if at least 5 data points were available. For country, dummy variables were created. The country having (1) the lowest prevalence and (2) more than one data point was selected as reference.

Meta-analysis was performed using STATA 12 Software Version 12.0. Prevalence was reported by 95 % confidence intervals (CIs). Random effects models were used, taking into account the possibility of heterogeneity between studies, which was tested with the Cochrane Q test and I2 test. We calculated prediction intervals (PI) to evaluate the dispersion of the estimated prevalence’s.

Subgroup analyses were conducted for results controlling (either by standardization or statistical adjustments) for risk group of infection and country. We performed analyses stratified by geographic area and year of field work.

Results

A total of 3400 references were identified in the three databases (Fig. 1). Most of them were excluded after revising the abstracts. Fifty-three full text citations were included. Only seven studies from the LILACS and one from the SciELO database were included as most of the citations were already found in PubMed. Fifty five studies were excluded; seven due to small sample size, five among drug users, one among prison inmates and one among MSM, from Brazil, Puerto Rico and Mexico. Prevalence was in range with included studies.

Seventy-five data points from the following countries were available for current/past HCV infection: Argentina, Brazil, Colombia, Dominican Republic, Mexico, Panama, Peru, Puerto Rico, Uruguay and Venezuela. For current HCV infection, based on HCV-RNA, 11 data points from the following countries were included: Brazil, Mexico, and Venezuela. The baseline characteristics of the studies appear in Electronic Supplemental Material, Table 2.

All data for transgender populations were from studies focusing on sex workers or conflating transgender and MSM. Therefore, the transgender population was not investigated separately.

Quality of studies

Results of the study quality assessment are provided in Electronic Supplemental Material, Table 3. Eighty-eight percent of studies reported sampling methods, most of them using non-probability sampling (70 %). Measurement of HCV was by laboratory testing for all studies. Thirteen studies had samples sizes of 100 or less and the median sample size of those with sample size >100 was 270 (interquartile range Q25–Q75: 197–500). All the studies used serological markers to diagnose hepatitis C infection and the testing assays were specified in 96 % of the studies. In the majority of cases, a single enzyme immunoassay was used. Confirmatory or supplementary testing was done by immunoblot assays in 20 % of records.

Sex workers

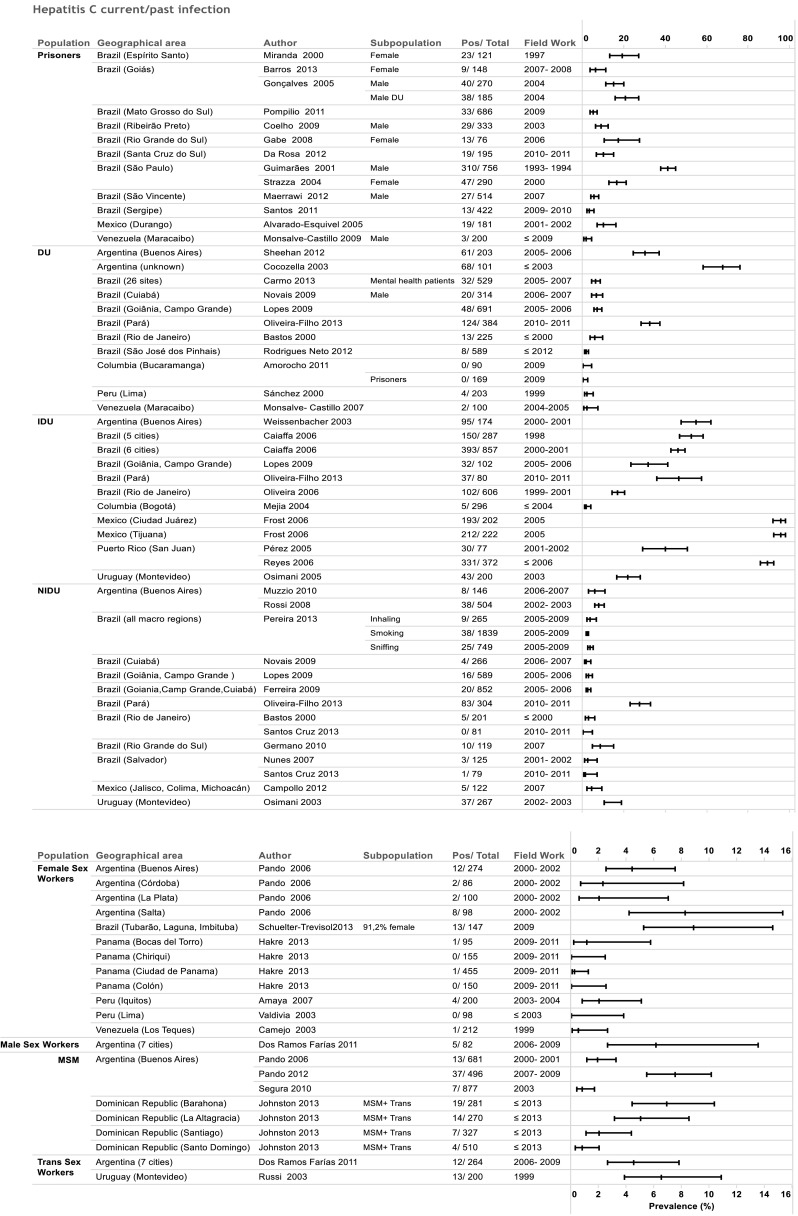

Eight studies met the inclusion criteria, leading to 15 data points on past/current HCV prevalence (Fig. 2) and no data on current HCV infection prevalence.

Fig. 2.

Forest plot for hepatitis C infection prevalence in Latin America and the Caribbean from 2000 to 2013. DU drug users, IDU injecting drug users, NI DU non-injecting drug users, MSM men who have sex with men

Most of the studies focused on female sex workers in five countries. The minimum age of participants was 18 years old, with average age around 27–29 years old in 8 studies, and three studies had average age of 33–36 years old. Current/past infection rate of HCV was below 2 % in Panama (Hakre et al. 2013), Peru (Valdivia et al. 2003; Guerra Amaya et al. 2007) and Venezuela (Camejo and Díaz 2003), and was 0 % in three locations (Chiriquí and Colón in Panama, and Lima, Peru). Highest values were in Argentina (Salta) and Brazil (Southern region of Santa Catarina State) with values up to 9 % (the latter study included 9 % male sex workers and 56 % of the sample inhaled illicit drugs). The pooled weighted estimate for current/past HCV infection among sex workers in Latin America based on available studies was 2 % (CI 95 % 1.0–3.4 %) with significant heterogeneity (p = 0.00) PI (0.56, 5.32).

Among transgender sex workers, current/past HCV prevalence was available from two studies with figures similar to those from studies among female sex workers in Argentina and counting among the higher results found in the region (7 % in Montevideo, and 5 % in seven cities in Argentina) (Dos Ramos Farias et al. 2011; Russi et al. 2003). The latter study also provided HCV prevalence for male sex workers (current/past HCV prevalence of 6 %).

Men who have sex with men

Seven data points from Argentina and Dominican Republic were analyzed (Fig. 2). Two studies reported an average participant age of 30 years old and in four study sites the majority of participants (54–68 %) were <24 years old (Johnston et al. 2013). No studies used HCV-RNA assays, thus no data were available for current HCV infection. Three studies from Buenos Aires seem to support an increase in HCV prevalence between 2001–2003 and 2009 (Pando et al. 2006a, b, 2012; Segura et al. 2010). The pooled estimate value for current/past HCV prevalence was 3 % (CI 95 % 1.7–4.5 %) with statistically significant heterogeneity, PI (−1.12, 8.23).

Prison inmates

Thirteen studies from Brazil, Venezuela (Monsalve-Castillo et al. 2009) and Mexico (Alvarado-Esquivel et al. 2005) provided 14 data points for analysis; the majority of studies were from Brazil (Fig. 2).

Multiple regression analysis indicated that anti-HCV prevalence in prisons has gone down within 15 years (p value 0.001). In Brazil, the oldest study from Sao Paulo with 18.6 % of inmates reporting previous intravenous drug use had an extremely high prevalence of 41 % (Guimaraes et al. 2001). The most recent study was from 2011 (Santa Cruz do Sul) and gave a prevalence of 10 % for anti-HCV (Rosa et al. 2012). In the 2004 study in a prison in Goia, HCV prevalence was 15 %, but increased to 21 % among drug users (Gonçalves 2005). Pooled prevalence for current/past HCV among inmate population was 12.5 % (CI 95 % 7.7–17.3 %) but heterogeneity was statistically significant (p < 0.000), PI (10.67, 19.51).

HCV-RNA indicating current HCV infection was analyzed in all three countries. In Brazil, prevalence was stable at around 3 % in three different studies (Santos et al. 2011; Barros et al. 2013; Pompilio et al. 2011). Prevalence in Venezuela (Monsalve-Castillo et al. 2009) was significantly lower than in Brazil. All except one study evaluated genotypes. Taken these studies together, genotypes were determined in 50 individuals, of which 90 % had genotype 1, being 1a the most common. 8 % had genotype 3.

In three of the five studies, more than 80 % of the anti-HCV positive cases were also HCV-RNA positive. Nevertheless, two studies from Brazil presented a much higher percentage of past infection (Barros et al. 2013; Pompilio et al. 2011).

No significant difference in HCV prevalence was seen by sex in the multiple regression analysis.

Drug users

Eight countries presented data on hepatitis C prevalence in drug users (DU) resulting in 39 data points (Fig. 2), some distinguishing between injecting (IDU) and non-injecting drug users (NIDU) (Ferreira et al. 2009; Bastos et al. 2000; Campollo et al. 2012; Germano et al. 2010; Lopes et al. 2009; Muzzio 2010; Novais et al. 2009; Nunes et al. 2007; Osimani 2003; Pereira et al. 2013; Rossi et al. 2008; Santos Cruz et al. 2013).

Prevalence for anti-HCV in DU remained below 7 % in the majority of studies. However, infection rates for current/past HCV infection among DU were up to 67 % in Argentina in a study conducted in 2003 (Cocozella et al. 2003), and 30 % in 2006 (Sheehan et al. 2012) (prevalence of ever-having injected drugs in both samples was 43 %). A 2011 study from Brazil also showed a current/past HCV infection rate of 32 % (Oliveira-Filho et al. 2013). In DU among mental health patients, no difference in prevalence was seen for DU compared to other studies (Carmo et al. 2013).

Data for anti-HCV among NIDU ranged from 0 to 10 % with the highest values found in a recent study from Brazil (8 %) (Germano et al. 2010), and Uruguay (10 % in 2003) (Osimani and Latorre 2003). The pooled value was 3.6 % (CI 95 % 2.6–4.5 %), PI (2.34, 7.58).

HCV infection rate for IDU varied considerably between and within countries (Brazil, Puerto Rico). The highest values were found in Argentina (55 % in 2001) (Weissenbacher et al. 2003), Brazil (53 % in 1998, 46 % in 2001) (Caiaffa et al. 2006), Puerto Rico (89 % in 2006) (Reyes et al. 2006) and Mexico (Ciudad Juarez and Tijuana) (96 % in 2005) (Frost et al. 2006). A study from Colombia (Bogota) found the lowest anti-HCV prevalence (1.7 %) in IDU (Mejia and Perez 2004). The latter is in agreement with another study conducted in another part of Columbia that indicated an absence of anti-HCV in DU and also in prison inmates who were drug users (Bautista Amorocho et al. 2011). Pooled regional anti-HCV prevalence among IDU was 49 % (CI 95 % 22.6–76.3 %) with significant heterogeneity among studies (p < 0.01), PI (33.45, 62.76).

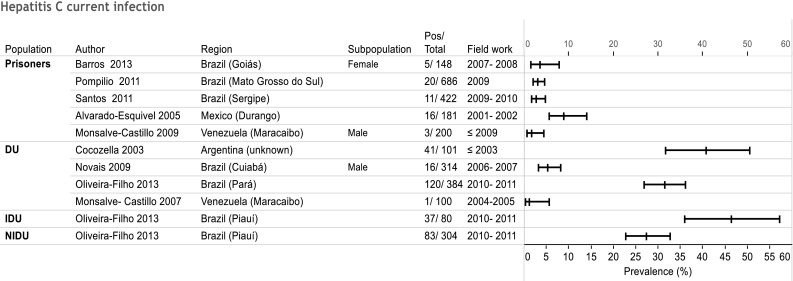

Four studies investigated both anti-HCV and HCV-RNA infection rate in DU, with six data points in total (Cocozella et al. 2003; Novais et al. 2009; Oliveira-Filho et al. 2013; Monsalve-Castillo et al. 2007) (Fig. 3). In all but one study (Oliveira-Filho et al. 2013), prevalence was much lower for HCV-RNA. HCV-RNA prevalence was much higher in IDU than in DU and NIDU in the study by Oliviera-Filho et al. who investigated all three populations. Only three studies from Brazil (Lopes et al. 2009; Novais et al. 2009; Oliveira-Filho et al. 2013) determined HCV genotypes. The study from Pará found a high prevalence of genotype 1b (42 %), especially in NIDU (50 %), while in the other two studies, individuals had genotype 1a in over 60 %.

Fig. 3.

Forest plot for current Hepatitis C infection prevalence Hepatitis C infection in Latin America and the Caribbean from 2000 to 2013. DU drug users, IDU injecting drug users, NIDU non-injecting drug users

Comparison of results among population groups

For HCV current/past infection, IDU presented the highest prevalence (Fig. 2). The study from Mejia and Perez was the only to report a prevalence below 10 %. Among DU, NIDU belonged to the less at risk populations, similar to those found among MSM (with values below 10 %, range 0–10 %). SW, MSM and NIDU summary regional estimates for HCV current or past infection are 2, 3 and 3.6 %, respectively. Prison inmates presented higher values, with a regional value of 12.5 %, with prevalence rates declining over the years.

Information on HCV current infection prevalence was only available in two of the five groups of interest (Fig. 3). In general, it was lower than anti-HCV infection rates, ranging from 1 to 46 %. It was below 10 % in all studies on prison inmates.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first review that systematically summarizes data on hepatitis C prevalence in five key populations from LAC. More than 50 % of studies investigated drug users. There was a significant lack of studies for male sex workers and the transgender population.

Nearly 50 % of all publications included were from Brazil. There are no data for many countries in the region, and studies from only ten countries were included overall. Whereby, the need for greater investment in HCV surveillance studies is high. As reported by the World Health Organization’s Global policy report on the prevention and control of viral hepatitis (WHO 2013a, b), more than 70 % of WHO member countries in LAC indicated that WHO assistance would be necessary for “viral hepatitis surveillance” and “estimating the national burden of viral hepatitis”.

As shown by this review, HCV prevalence results agree with the common epidemiological knowledge on HCV transmission routes. When analyzing HCV prevalence among MSM in the region (pooled 3 % anti-HCV prevalence), we must consider that there can be overlapping injecting drug use and HIV co-infection. Prevalence values appear in consonance with Buffington et al. who report 1.5–3.6 % HCV prevalence among non-injecting and injecting MSM, respectively, in several USA cities (Buffington et al. 2007) or 2.1 % HCV prevalence among MSM clinic attendees in England (Ward and Lee 2014). Results suggest that this population presents a higher risk of HCV than the general population highlighting the need for a greater focus on surveillance and services for MSM (Tohme and Holmberg 2010; Ponde 2011). The rate of infection due to sexual transmission is believed to be low, but factors such as unprotected sex with multiple sex partners, traumatic sex, co-infection with HIV or other STIs increase the risk of transmission and chronicity once infected with HCV (Terrault et al. 2013).

This review focused on vulnerable and risk groups that can have overlapping risk behaviors for HCV transmission. The authors recognize the limitations as information on overlapping risk behaviors in most cases was not readily available for this review.

This study updates and adds-on to reviews on HCV among injecting drug users worldwide (Aceijas and Rhodes 2007; Nelson et al. 2011). Our findings confirm Aceijas and Rhodes review that indicated important variation of HCV prevalence among IDUs in the region. The findings are also consistent with global figures. Nelson et al. found, globally, HCV prevalence among IDUS between 60 and 80 % in 26 countries, and in USA, Russia and China, countries with the largest amount of IDUs, HCV prevalence is estimated from 67 to 73 %. HCV prevalence among FSW was among the lowest found in some countries, and varying prevalence most likely reflects varying levels of injecting drug use. Findings among sex workers are consistent with studies in other regions (Chen et al. 2015; Praseeda et al. 2013; Rantala and van de Laar 2008). For prison inmates, the pooled estimates concur with the regional estimates provided by Larney et al. (2013) and are lower than those in Asia, Europe and North America.

With regard to the diagnosis of HCV infection, all studies used anti-HCV positivity as serological marker that does not distinguish between current and past HCV infection. Only a few publications evaluated HCV-RNA, and even fewer evaluated genotypes of HCV infection. This is likely related to the fact that testing for HCV-RNA and genotyping is technically more complicated and costly. Nevertheless, burden of disease for current HCV infection measured by HCV-RNA and genotyping is of great interest from an epidemiological as well as treatment response perspective.

All publications that evaluated genotypes were studies in Brazilian drug users. Data suggest that genotype 1a might not always be the predominant type (Oliveira-Filho et al. 2013). Further investigation in other countries and key populations are needed to support policies for therapeutic schemes.

Among the limitations of the study are a low sample size cutoff criteria (75 participants or greater) that were decided upon given the paucity of studies in the region and different sampling methodology that could bias prevalence results. Thirteen percent of the fifty five studies were excluded because of a small sample size, but results were not significantly different in prevalence rates from those with higher sample sizes. Another limitation is that the full data extraction was conducted by only one reviewer with an additional reviewer for only a sample of studies. While there was full agreement between reviewers for the sample reviewed by both, variations in data collection could occur for the additional studies not reviewed by both. Other limitation for providing pooled results is the high heterogeneity present among HCV prevalence in the studies. The high heterogeneity in the different analysis can be explained by differences in years of publication of the studies, inherent differences between risk groups and geographic locations. This high heterogeneity may limit the value of the regional summary measures presented; however, differences among prevalence values were expected and could be ascribed to true differences in the prevalence of infection among risk groups and geographical areas. Results can also be affected due to overlapping HIV/HCV epidemics, mainly in IDU and prison inmates. It is important to consider that HIV infection is significant in the same population groups studied for HCV and co-infection results in a more rapid progression of liver disease and HCV-related liver disease is a major cause of death for people living with HIV. Prevalence figures of HCV can be affected because the likelihood of chronic infection of HCV is higher for people living with HIV, while, on the other hand, mortality may be higher among persons co-infected by HCV and HIV.

This systematic review and meta-analysis summarized and assessed trends in prevalence of hepatitis C infection in high risk populations of the region using conventional methods for combining study data. Thus, the Forrest plots presented do not compare risk ratios or other comparative summary measures but prevalence of Hepatitis C. The search strategy included different databases such as Pubmed and Lilacs which is a specific source of scientific articles in the region; we did not include the EMBASE database due to lack of access to such database.

In conclusion, these findings emphasize the need to strengthen surveillance of hepatitis C prevalence targeted towards key populations in LAC using a broader framework of risk and vulnerability. Based on these findings, prevention and treatment strategies should include and focus on most-at-risk and vulnerable populations to respond to the epidemic of hepatitis C infection.

Electronic supplementary material

Conflict of interest

None.

Abbreviations

- LAC

Latin America and the Caribbean

- IDU

Injecting drug users

- NIDU

Non-injecting drug users

- MSM

Men who have sex with men

- HCV

Hepatitis C virus

- DU

Drug users

Footnotes

This review is part of the special issue “Driving the Best Science to Meet Global Health Challenges” edited on the occasion of the 9th European Congress on Tropical Medicine and International Health 2015.

References

- Aceijas C, Rhodes R. Global estimates of prevalence of HCV infection among injecting drug users. Int J Drug Policy. 2007;18(5):352–358. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2007.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvarado-Esquivel C, Sablon E, Martinez-Garcia S, et al. Hepatitis virus and HIV infections in inmates of a state correctional facility in Mexico. Epidemiol Infect. 2005;133(4):679–685. doi: 10.1017/S0950268805003961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barros LA, Pessoni GC, Teles SA, et al. Epidemiology of the viral hepatitis B and C in female prisoners of Metropolitan Regional Prison Complex in the State of Goias, Central Brazil. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2013;46(1):24–29. doi: 10.1590/0037-868216972013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bastos FI, Lowndes CM, Castello-Branco LR, et al. Sexual behaviour and infection rates for HIV, blood-borne and sexually transmitted infections among patients attending drug treatment centres in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Int J STD AIDS. 2000;11(6):383–392. doi: 10.1258/0956462001916100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bautista Amorocho H, Jaimes Moreno BZ, Hincapié López ML. Ausencia de infección por virus de la hepatitis C en usuarios de drogas ilícitas en la ciudad de Bucaramanga, Colombia’s Absence of hepatitis C infection among illegal drug users in Bucaramanga, Colombia. Rev Colomb Gastroenterol. 2011;26(1):15–20. [Google Scholar]

- Buffington J, Murray PJ, Schlanger K, et al. Low prevalence of hepatitis C virus antibody in men who have sex with men who do not inject drugs. Public Health Report. 2007;122(Suppl. 2):63–67. doi: 10.1177/00333549071220S212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caiaffa WT, Bastos FI, Freitas LL, et al. The contribution of two Brazilian multi-center studies to the assessment of HIV and HCV infection and prevention strategies among injecting drug users: the AjUDE-Brasil I and II Projects. Cad Saude Publica. 2006;22(4):771–782. doi: 10.1590/S0102-311X2006000400016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camejo MI, Díaz M. Prevalencia de hepatitis B, hepatitis C y sífilis en trabajadoras sexuales de Venezuela. Rev Saúde Pública. 2003;37(3):339–344. doi: 10.1590/S0034-89102003000300012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campollo O, Roman S, Panduro A, et al. Non-injection drug use and hepatitis C among drug treatment clients in west central Mexico. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2012;123(1–3):269–272. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmo RA, Campos LN, Melo AP, et al. Hepatitis C among patients with mental illness in Brazil: an analysis of associated factors. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2013;35(2):129–133. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2012.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Shen Z, Morano J, et al. Bridging the epidemic: a comprehensive analysis of prevalence and correlates of HIV, Hepatitis C, and syphilis, and infection among female sex workers in Guangxi Province, China. PLoS One. 2015;10(2):1–15. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0115311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cocozella DR, Albuquerque MM, Borzi S, et al. Prevalence of hepatic involvement, alcoholism, hepatis B, C and HIV in patients with background history of drug use] Act Gastroenterol Latinoam. 2003;33(4):177–181. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dos Ramos Farias MS, Garcia MN, Reynaga E, et al. First report on sexually transmitted infections among trans (male to female transvestites, transsexuals, or transgender) and male sex workers in Argentina: high HIV, HPV, HBV, and syphilis prevalence. IJID. 2011;15(9):e635–e640. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2011.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira RC, Rodrigues FP, Teles SA, et al. Prevalence of hepatitis B virus and risk factors in Brazilian non-injecting drug users. J Med Virol. 2009;81(4):602–609. doi: 10.1002/jmv.21464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frost SD, Brouwer KC, Firestone Cruz MA, et al. Respondent-driven sampling of injection drug users in two U.S.-Mexico border cities: recruitment dynamics and impact on estimates of HIV and syphilis prevalence. J Urban Health Bull N Y Acad Med. 2006;83(6 Suppl):i83–i97. doi: 10.1007/s11524-006-9104-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Germano FN, dos Santos CA, Honscha G, et al. Prevalence of hepatitis C virus among users attending a voluntary testing centre in Rio Grande, southern Brazil: predictive factors and hepatitis C virus genotypes. Int J STD AIDS. 2010;21(7):466–471. doi: 10.1258/ijsa.2009.009089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonçalves K (2005) História de vida e situação de saúde no ambiente prisional de Goiás: estudo da prevalência de hepatite C em detentos [Dissertation]. Goiânia: Universidade Católica de Goiás

- Guerra Amaya O, et al. Seroprevalence of antibodies against hepatitis C virus in female sex workers patients from the sexually transmitted infections reference center in Iquitos, Peru. Acta Med Peruana. 2007;24(2):26–30. [Google Scholar]

- Guimaraes T, Granato CF, Varella D, et al. High prevalence of hepatitis C infection in a Brazilian prison: identification of risk factors for infection. Braz J Infect Dis. 2001;5(3):111–118. doi: 10.1590/S1413-86702001000300002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hakre S, Arteaga G, Nunez AE, et al. Prevalence of HIV and other sexually transmitted infections and factors associated with syphilis among female sex workers in Panama. Sex Trans Infect. 2013;89(2):156–164. doi: 10.1136/sextrans-2012-050557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LG, Vaillant TC, Dolores Y, et al. HIV, hepatitis B/C and syphilis prevalence and risk behaviors among gay, transsexuals and men who have sex with men, Dominican Republic. Int J STD AIDS. 2013;24(4):313–321. doi: 10.1177/0956462412472460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kershenobich D, Razavi HA, Sanchez-Avila JF, et al. Trends and projections of hepatitis C virus epidemiology in Latin America. Liver Int. 2011;31(Suppl 2):18–29. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2011.02538.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larney S, Kopinski H, Beckwith CG, et al. The incidence and prevalence of hepatitis C in prisons and other closed settings: results of a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hepatology. 2013;58(4):1215–1224. doi: 10.1002/hep.26387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavanchy D. Evolving epidemiology of hepatitis C virus. Clin Microb Infect. 2011;17(2):107–115. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2010.03432.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopes CL, Teles SA, Espirito-Santo MP, et al. Prevalence, risk factors and genotypes of hepatitis C virus infection among drug users, Central-Western Brazil. Rev Saude Publica. 2009;43(Suppl 1):43–50. doi: 10.1590/S0034-89102009000800008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mejia I, Perez A (2004) Low seroprevalence in a risky environment: an analysis of risk and protective factors based on findings from an IDU study in Bogota, Colombia. In: 15th international conference on the reduction of drug related harm. Melbourne, Australia

- Mohd Hanafiah K, Groeger J, Flaxman AD, et al. Global epidemiology of hepatitis C virus infection: new estimates of age-specific antibody to HCV seroprevalence. Hepatology. 2013;57(4):1333–1342. doi: 10.1002/hep.26141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monsalve-Castillo F, Gómez-Gamboa L, Albillos A, et al. Virus de hepatitis C en poblaciones de riesgo a adquirir la infección. Venezuela. Rev Esp Enferm Dig (Madrid) 2007;99(6):315–319. doi: 10.4321/s1130-01082007000600002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monsalve-Castillo F, Chacin-Bonilla L, Atencio RJ, et al. Low prevalence of hepatitis C virus infection in a prisoner population from Maracaibo, Venezuela. Biomedica. 2009;29(4):647–652. doi: 10.7705/biomedica.v29i4.142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muzzio E. Infecciones y otros problemas de salud en usuarios de pasta base de cocaína en un centro asistencial de Buenos Aires, Argentina. Rev Argent Salud Pública. 2010;1(4):5. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson P, Mathers B, Cowie B, Hagan H, et al. The epidemiology of viral hepatitis among people who inject drugs: results of global systematic reviews. Lancet. 2011;378(9791):571–583. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61097-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novais AC, Lopes CL, Reis NR, et al. Prevalence of hepatitis C virus infection and associated factors among male illicit drug users in Cuiaba, Mato Grosso, Brazil. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2009;104(6):892–896. doi: 10.1590/S0074-02762009000600012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nunes CL, Andrade T, Galvão-Castro B, et al. Assessing risk behaviors and prevalence of sexually transmitted and blood–borne infections among female crack cocaine users in Salvador—Bahia, Brazil. Braz J Infect Dis. 2007;11(6):561–566. doi: 10.1590/S1413-86702007000600007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira-Filho AB, Sawada L, Pinto LC, et al. HCV infection among cocaine users in the state of Para, Brazilian Amazon. Arch Virol. 2013;158(7):1555–1560. doi: 10.1007/s00705-013-1627-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osimani ML (2003) Prácticas de riesgo y prevalencia de infecciones por virus de inmunodeficiencia humana (VIH), hepatitis B (VHB), hepatitis c (VHC) y T. Pallidum (Sífilis) en usuarios de cocaína no inyectable. Instituto IDES, Montevideo, Uruguay

- Osimani ML, Latorre L (eds) (2003) Usuarios de cocaina: prácticas de riesgo y prevalencia de infecciones por VIH, hepatitis B, hepatitis C y T pallidum. Instituto IDES, Montevideo

- Pando MA, Bautista CT, Maulen S, et al. Epidemiology of human immunodeficiency virus, viral hepatitis (B and C), treponema pallidum, and human T-cell lymphotropic I/II virus among men who have sex with men in Buenos Aires, Argentina. Sex Trans Dis. 2006;33(5):307–313. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000194578.06795.2d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pando MA, Berini C, Bibini M, et al. Prevalence of HIV and other sexually transmitted infections among female commercial sex workers in Argentina. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2006;74(2):233–238. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pando MA, Balan IC, Marone R, et al. HIV and other sexually transmitted infections among men who have sex with men recruited by RDS in Buenos Aires, Argentina: high HIV and HPV infection. PLoS One. 2012;7(6):e39834. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0039834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pereira LM, Martelli CM, Moreira RC, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of Hepatitis C virus infection in Brazil, 2005 through 2009: a cross-sectional study. BMC Infect Dis. 2013;13:60. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-13-60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perz JF, Armstrong GL, Farrington LA, et al. The contributions of hepatitis B virus and hepatitis C virus infections to cirrhosis and primary liver cancer worldwide. J Hepatology. 2006;45(4):529–538. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2006.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pompilio MA, Pontes ERJC, Castro ARCM, et al. Prevalence and epidemiology of chronic hepatitis C among prisoners of Mato Grosso do Sul State, Brazil. J Venom Anim Toxins Incl Trop Dis. 2011;17(2):216–222. doi: 10.1590/S1678-91992011000200013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ponde RA. Hidden hazards of HCV transmission. Med Microbiol Immunol. 2011;200(1):7–11. doi: 10.1007/s00430-010-0159-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Praseeda SD, Anuradha D, Jayanthi SS. A study on the HBV and the HCV infections in female sex workers and their co-infection with HIV. J Clin Diagn Res JCDR. 2013;7(2):234–237. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2013/4322.2735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team (2011) R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing. Vienna, Austria

- Rantala M, van de Laar MJ. Surveillance and epidemiology of hepatitis B and C in Europe—a review. Euro Surveill. 2008;13(21):18880. doi: 10.2807/ese.13.21.18880-en. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reyes JC, Colon HM, Robles RR, et al. Prevalence and correlates of hepatitis C virus infection among street-recruited injection drug users in San Juan, Puerto Rico. J Urban Health. 2006;83(6):1105–1113. doi: 10.1007/s11524-006-9109-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosa F, Carneiro M, Duro LN, et al. Prevalence of anti-HCV in an inmate population. Rev Soc Med Brasileira. 2012;58(5):557–560. doi: 10.1016/S0104-4230(12)70249-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossi D, Radulich G, Muzzio E, et al. Multiple infections and associated risk factors among non-injecting cocaine users in Argentina. Cad Saude Publica. 2008;24(5):965–974. doi: 10.1590/S0102-311X2008000500003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russi JC, Serra M, Vinoles J, et al. Sexual transmission of hepatitis B virus, hepatitis C virus, and human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infections among male transvestite comercial sex workers in Montevideo, Uruguay. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2003;68(6):716–720. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos Cruz M, Andrade T, Bastos FI, et al. Key drug use, health and socio-economic characteristics of young crack users in two Brazilian cities. Int J Drug Policy. 2013;24(5):432–438. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2013.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos BF, de Santana NO, Franca AV. Prevalence, genotypes and factors associated with HCV infection among prisoners in Northeastern Brazil. World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17(25):3027–3034. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v17.i25.3027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segura M, Bautista CT, Marone R, et al. HIV/STI co-infections, syphilis incidence, and hepatitis B vaccination: the Buenos Aires cohort of men who have sex with men. AIDS Care. 2010;22(12):1459–1465. doi: 10.1080/09540121003758556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheehan HB, Benetucci J, Muzzio E, et al. High rates of serum selenium deficiency among HIV- and HCV-infected and uninfected drug users in Buenos Aires, Argentina. Pub Health Nutr. 2012;15(3):538–545. doi: 10.1017/S1368980011001364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szabo SM, Bibby M, Yuan Y, et al. The epidemiologic burden of hepatitis C virus infection in Latin America. Ann Hepatol. 2012;11(5):623–635. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terrault NA, Dodge JL, Murphy EL, et al. Sexual transmission of hepatitis C virus among monogamous heterosexual couples: the HCV partners study. Hepatology. 2013;57(3):881–889. doi: 10.1002/hep.26164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tohme RA, Holmberg SD. Is sexual contact a major mode of hepatitis C virus transmission? Hepatology. 2010;52(4):1497–1505. doi: 10.1002/hep.23808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valdivia JA, Rivera S, Ramirez D, et al. Hepatitis C virus infection in female sexual workers from northern Lima. Rev Gastroenterol Peru. 2003;23(4):265–268. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward C, Lee V. Should we offer routine hepatitis C antibody testing in men who have sex with men? J Int AIDS Soc. 2014;17(4 Suppl 3):19591. doi: 10.7448/IAS.17.4.19591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weissenbacher M, Rossi D, Radulich G, et al. High sero prevalence of blood borne viruses among street-recruited injection drug users from Buenos Aires, Argentina. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;37(Suppl 5):S348–S352. doi: 10.1086/377560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong WC, Cheung CS, Hart GJ. Development of a quality assessment tool for systematic reviews of observational studies (QATSO) of HIV prevalence in men having sex with men and associated risk behaviours. Emerg Themes Epidemiol. 2008;5:23. doi: 10.1186/1742-7622-5-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (2010) Viral hepatitis: WHA 63.18. Sixty-third World Health Assembly. Geneva

- World Health Organization (2013) Consolidated guidelines on the use of antiretroviral drugs for treating and preventing HIV infection: recommendations for a public health approach. In: World Health Organization., ed. World Health Organization, Geneva [PubMed]

- World Health Organization (2013) Global policy report on the prevention and control of viral hepatitis in WHO member states. Geneva. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/85397/1/9789241564632_eng.pdf?ua=1. Accessed 22 Feb 2014

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.