Abstract

Background

Very brief single-item screening questions (SISQs) for alcohol and other drug use can facilitate screening in health care settings, but are not widely used. Self-administered versions of the SISQs could ease barriers to their implementation.

Objective

We sought to validate SISQs for self-administration in primary care patients.

Design

Participants completed SISQs for alcohol and drugs (illicit and prescription misuse) on touchscreen tablet computers. Self-reported reference standard measures of unhealthy use, and more specifically of risky consumption, problem use, and substance use disorders, were then administered by an interviewer, and saliva drug tests were collected.

Participants

Adult patients aged 21–65 years were consecutively enrolled from two urban safety-net primary care clinics.

Main Measures

The SISQs were compared against reference standards to determine sensitivity, specificity, and area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC) for alcohol and drug use.

Key Results

Among the 459 participants, 22 % reported unhealthy alcohol use and 25 % reported drug use in the past year. The SISQ-alcohol had sensitivity of 73.3 % (95 % CI 65.3–80.3) and specificity of 84.7 % (95 % CI 80.2–88.5), AUC = 0.79 (95 % CI 0.75–0.83), for detecting unhealthy alcohol use, and sensitivity of 86.7 % (95 % CI 75.4–94.1) and specificity of 74.2 % (95 % CI 69.6–78.4), AUC = 0.80 (95 % CI 0.76–0.85), for alcohol use disorder. The SISQ-drug had sensitivity of 71.3 % (95 % CI 62.4–79.1) and specificity of 94.3 % (95 % CI 91.3–96.6), AUC = 0.83 (95 % CI 0.79–0.87), for detecting unhealthy drug use, and sensitivity of 85.1 (95 % CI 75.0–92.3) and specificity of 88.6 % (95 % CI 85.0–91.6), AUC = 0.87 (95 % CI 0.83–0.91), for drug use disorder.

Conclusions

The self-administered SISQs are a valid approach to detecting unhealthy alcohol and other drug use in primary care patients. Although self-administered SISQs may be less accurate than the previously validated interviewer-administered versions, they are potentially easier to implement and more likely to retain their fidelity in real-world practice settings.

KEY WORDS: Screening, Substance use, Validation, Alcohol, Illicit drugs

INTRODUCTION

Screening followed by brief intervention for unhealthy alcohol use in adult primary care patients is recommended by the United States Preventive Services Task Force, and is among the most cost-effective prevention services.1–4 Screening, brief intervention, and referral to treatment (SBIRT) programs, which address drug use as well as alcohol, have been widely promoted and disseminated with the support of federal agencies.5–7 While the efficacy of SBIRT for reducing drug use in U.S. populations has not been clearly established,8–11 screening in medical settings may be justified on clinical grounds. These include the impact of drug use on prevention and treatment of other medical conditions,12 drug–medication interactions,13,14 effects on adherence,15,16 risk of prescription opioid overdose,17 and potential to improve health-related quality of life.18

Nonetheless, screening - even for alcohol alone - has proven difficult to implement and sustain in regular primary care practice.19–21 In recent years, some implementation barriers have been eased by the development of validated single-item screening questions (SISQs) to identify unhealthy use of alcohol and drugs.22,23 The SISQs are brief enough to be easily incorporated into time-pressured practice settings, and have demonstrated high sensitivity and specificity for identification of unhealthy use in primary care patients. A recent study indicates that the SISQs may even be able to accurately identify and distinguish substance dependence.24

SISQs in studies to date have been asked by an interviewer, and this approach has limitations in some practice settings. Interviewer-administered questions can lose their fidelity when administered outside the research context, even by trained staff.25,26 The interviewer-administered approach may also be difficult to incorporate into clinical workflows,27,28 and patients may be less comfortable answering questions face-to-face about a stigmatized behavior such as substance use.29–31

A self-administered version of the SISQs may be preferable in some practice settings, but the validity of adapting the SISQs to a self-administered format must be established before this approach can be widely recommended. Our goal was to test the sensitivity and specificity of the SISQs, as well as their feasibility, when they were self-administered by adult primary care patients using touchscreen tablet computers. Computer self-administration was chosen instead of a paper format because it may allow for easier integration with electronic health records and Web-based patient portals.

METHODS

Participants and Recruitment

Participants were recruited from two safety-net hospital-based adult primary care clinics; Site A was located in Boston and Site B in New York City. Data were collected at Site A in June and July 2012 and at Site B from November 2012 through June 2013. Eligible individuals were 21–65 years of age, English-speaking, and current clinic patients. We excluded individuals over age 65 because the lower prevalence of unhealthy drug and alcohol use in this age group32,33 would not have supported meaningful analyses in our sample.

Participants were recruited consecutively while they were waiting for medical appointments. At Site A, each patient who presented for a scheduled clinic visit was approached, while at Site B patients were recruited from the waiting area using a pre-specified path.22,23 The institutional review boards of New York University School of Medicine and Boston Medical Center approved all study procedures.

Study Procedures

Study visits were conducted in a private room, and participants were informed that responses to assessments were anonymous and confidential. Participants completed the SISQs independently using a touchscreen tablet computer. Any requests for assistance were recorded on paper by a research assistant (RA). Following completion of the SISQs, the RA administered a series of interviews that served as reference standard comparison measures. Saliva testing was offered only to Site B participants, who were informed of the voluntary saliva test after completing all self-reported interviews, and were asked to provide a second informed consent. The total time to complete all study procedures was 30–45 min for most participants.

Measures

Standard demographic data were collected. Health literacy was measured using the Rapid Estimate of Adult Literacy in Medicine (REALM), and standard cutoffs were applied to interpret REALM scores as below or at/above high school level.34

Experimental Instruments: Single-Item Screening Questions (SISQs) for Alcohol and Drugs

The computer self-administered SISQs were identical to those previously validated as interviewer-administered questions.22,23 The alcohol SISQ asked “How many times in the past year have you had X or more drinks in a day?” (X = 5 for men, X = 4 for women). The drug SISQ asked “How many times in the past year have you used an illegal drug or used a prescription medication for non-medical reasons (for example, because of the experience or feeling it caused)?” Participants were instructed to enter a numeric response, and to enter zero if the answer was ‘never.’ Following the scoring system used for the interviewer-administered SISQs, responses were dichotomized, with any response greater than zero indicating a positive screen.

Reference Standard Measures

We compared the self-administered SISQ items to reference standard measures (Table 1) similar to those used in the prior validation studies of the interviewer-administered SISQs.22,23 A combination of these measures was used to define composite reference standard measures indicating unhealthy use, current risky use, problem use, and substance use disorder. A composite reference standard may be used when individual reference measures are imperfect.35

Table 1.

Combination of Reference Standard Measures Defining Unhealthy Use, Current Risky Use, Problem Use, and Substance Use Disorder

| Substance | Condition | Measures used to define the condition | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Timeline follow-back | SIP6 | SIP-D7 | MINI-Plus8 screening item | MINI-Plus8 abuse or dependence | ||

| Alcohol | Unhealthy use1 | + | + | + | + | |

| Current risky use2 | + | |||||

| Problem use3 | + | + | ||||

| Disorder4 | + | |||||

| Drugs | Unhealthy use | + | + | + | + | |

| Current risky use5 | + | |||||

| Problem use3 | + | + | ||||

| Disorder4 | + | |||||

1Any current risky use, problem use, or disorder

2Any use above the recommended limits (> 4 drinks/day or 14 drinks/week for men; > 3 drinks/day or 7 drinks/week for women) in the past 30 days

3Past-year use and at least one problem reported on the Short Inventory of Problems

4MINI positive for abuse or dependence

5Any use of a drug in the past 30 days

6Short Inventory of Problems (SIP) for alcohol

7Short Inventory of Problems for Drugs (SIP-D)

8Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview

Unhealthy use was defined as the presence of current risky use, problem use, or a substance use disorder. Current risky use was based on response to a 30-day timeline follow-back (TLFB) interview.36 An individual was classified as having risky alcohol use if s/he reported use in excess of guideline-recommended limits (5 drinks/day or 14 drinks/week for men; 4 drinks/day or 7 drinks/week for women).37 Risky drug use was any use of an illicit drug or misuse of a prescription medication (using more than prescribed, for reasons other than as prescribed, or without a prescription). At Site B, saliva testing provided an additional measure of current risky use. Testing was performed with the Intercept® immunoassay (OraSure Technologies, Inc., Bethlehem, PA, USA), which has a window of detection of up to 3 days for most drugs.38–40 To assist in the interpretation of results, participants were asked to report any medical use of medications that might be detected in the saliva test.

Problem use was defined as use in the past 12 months, with at least one self-reported consequence of use. Use in the past 12 months was assessed using the MINI-Plus (Version 6.0) screening items for alcohol and drug use.41–42 Consequences were measured using the Short Inventory of Problems (SIP) for alcohol, and the Short Inventory of Problems for Drugs (SIP-D).43,44Substance use disorder was determined by the MINI-Plus (Version 6.0).41–42 The MINI-Plus alcohol and drug modules are structured interviews to assess alcohol and drug use disorders, as defined by DSM-IV abuse or dependence.

Statistical Analysis

We examined descriptive statistics for the sample, including demographic characteristics and prevalence of unhealthy alcohol and drug use reported on the MINI-Plus (for past 12 months) and TLFB (for past 30 days).

Based on the composite reference standard measures, we calculated the sensitivity and specificity of the SISQ-alcohol and SISQ-drug. We computed positive and negative diagnostic likelihood ratios (DLRs) as an additional measure of the diagnostic value of the screening items.45 To provide a measure of discriminatory power, we computed receiver operator characteristic (ROC) curves and examined the area under each curve (AUC). Exact 95 % confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated for all accuracy estimates.

After completing sensitivity and specificity calculations for each site individually, we examined differences in the SISQ results (in comparison to reference standard measures) between the two sites by conducting chi-square analyses. To compare sites with respect to sensitivity, among those who were positive on the reference standard measures, we examined the cross-tabulation of site and SISQ result. Similarly, to compare sites with respect to specificity, we examined the cross-tabulation of site and SISQ result among those who were negative on the reference standard measures. SISQ results differed significantly for the two sites only for the comparison of specificity with respect to any unhealthy drug use. At Site B, there was a higher proportion of false-positive results on the SISQ for unhealthy drug use, with a false-positive fraction (defined as false positive ÷ [false positive + true negative]) of 14/129 at Site B versus 5/206 at Site A; p = 0.001). Because specificity was good at each site (98 % at Site A and 89 % at Site B), the decision was made to combine the two sites for all analyses.

The sensitivity and specificity of the SISQs for detecting unhealthy use was then estimated for a number of pre-specified subgroups in which prior studies have found substance use screening tools to have reduced precision or feasibility.23,46–48 These subgroups were as follows: male, age greater than 50, Hispanic/Latino, primary language other than English, born outside the U.S., and education or health literacy lower than high school level. To determine whether there were significant differences in SISQ accuracy for each subgroup, we performed chi-square analyses, cross-tabulating each subgrouping variable with the SISQ screening result, within groups that were positive (sensitivity) or negative (specificity) on the reference standard measures. Analyses were conducted using version 13 of Stata (StataCorp, 2013; StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA) and its diagnostic testing module.49

RESULTS

Recruitment

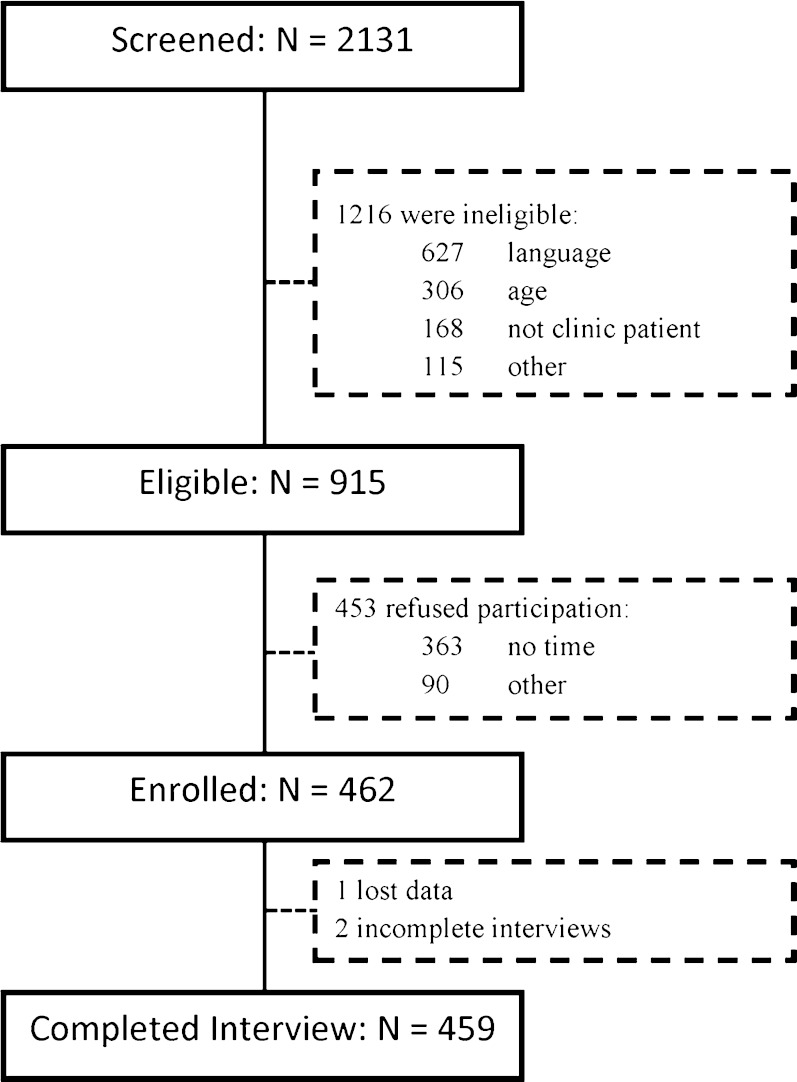

Of the 2131 individuals screened, 915 (43 %) were eligible, and 462 (50 % of those eligible) were enrolled (Fig. 1). Site A contributed 194 participants, and Site B 265 participants. At Site B, 230 (87 %) participants also participated in saliva testing for drug use.

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of participant recruitment at the two sites

Participant Characteristics

Demographic characteristics of participants are summarized in Table 2. Limited demographics of eligible individuals who refused to participate were collected at Site B. Compared to those who participated at Site B, non-participants were more frequently female (57 %), white (36 %), and younger (mean age 42 years). Prevalence of substance use in the past 12 months and past 30 days is reported in Table 3.

Table 2.

Demographic Characteristics of the 459 Participants

| Characteristic | |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | |

| Mean, SD | 46 (12) |

| Median | 48 |

| Range | 21–65 |

| Interquartile range | 19 |

| Gender | |

| Female | 236 (51.4) |

| Male | 221 (48.1) |

| Transgender | 2 (0.4) |

| Race/Ethnicity | |

| Black/African American | 238 (51.0) |

| White/Caucasian | 88 (19.1) |

| Hispanic | 93 (20.2) |

| Other | 38 (8.2) |

| Don’t Know/Refused | 2 (0.4) |

| Primary language | |

| English | 359 (78.2) |

| Spanish | 39 (8.5) |

| Other | 61 (13.3) |

| Country of birth | |

| U.S. | 296 (64.5) |

| Other | 163 (35.5) |

| Education (highest level completed) | |

| Less than HS | 64 (13.9) |

| HS grad or GED | 166 (36.2) |

| Some college or trade school | 116 (25.3) |

| College degree (4-year) | 90 (19.6) |

| Graduate school | 23 (5.0) |

| Health Literacy1 | |

| Below high school | 188 (41.0) |

| High school or greater | 271 (59.0) |

| Employment | |

| Employed | 170 (37.0) |

| Unemployed | 288 (62.7) |

| Don’t know/Refused | 1 (0.2) |

1Based on REALM-Short Form at Site A and full REALM at Site B. Standard cutoffs applied to determine education level in terms of years of completed schooling

Table 3.

Prevalence of Substance Use Based on Responses to MINI and Timeline Follow-Back (N = 459)

| Substance | Past-year use (MINI) N (%) |

Past-month use Timeline follow-back N (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Alcohol | 103 (22.4)a | 88 (19.2)b |

| Drugs | 114 (24.8)c | 73 (15.9) |

| Specific drug categories | ||

| Illicit drugs | 108 (23.5) | |

| Cannabis | – | 58 (12.6) |

| Cocaine | – | 12 (2.6) |

| Heroin | – | 10 (2.2) |

| Hallucinogens | – | 1 (0.2) |

| Prescription drugs (non-medical use) | 21(4.6) | |

| Opioids | – | 5 (1.1) |

| Benzodiazepines | – | 3 (0.7) |

| Stimulants | – | 2 (0.4) |

aAlcohol use on MINI as defined by positive response to item I1: “In the past 12 months, have you had 3 or more alcoholic drinks, within a 3 h period, on 3 or more occasions?”

bUnhealthy past 30 days alcohol use, defined using National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) guidelines of > 4 drinks/day or 14 drinks/week for men; > 3 drinks/day or 7 drinks/week for women

cDrug use on MINI as defined by a positive response to item J1: “In the past 12 months, did you take any of these drugs more than once, to get high, to feel elated, to get ‘a buzz’ or to change your mood?”

Sensitivity and Specificity

The accuracy of the SISQs in comparison to reference standard measures is presented in Table 4. For both the SISQ-alcohol and the SISQ-drug, sensitivity generally increased and specificity decreased as the level of risk rose from risky consumption to problem use or substance use disorder. Diagnostic likelihood ratios (DLRs) indicate that across both substances and all risk categories, participants with a substance use condition were at least three times as likely to have a positive screen, and were less than one-third as likely to have a negative screen. AUCs indicated good discrimination.50

Table 4.

Sensitivity, Specificity, Likelihood Ratios, and Area Under the Curve of the Single-Item Screening Questions for Alcohol and Drugs in Detecting Unhealthy Use, Current Risky Use, Problem Use and Substance Use Disorder (N = 459)

| Substance class | Positive on reference standards N (%) |

Sensitivity % (95 % CI) |

Specificity % (95 % CI) |

Positive LR (95 % CI) | Negative LR (95 % CI) | AUC (95 % CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any unhealthy use | ||||||

| Alcohol | 146 (31.8) | 73.3 (65.3, 80.3) | 84.7 (80.2, 88.5) | 4.8 (3.6, 6.3) | 0.32 (0.24, 0.41) | 0.79 (0.75, 0.83) |

| Drugs1 | 122 (26.7) | 71.3 (62.4, 79.1) | 94.3 (91.3, 96.6) | 12.6 (8.0, 19.7) | 0.30 (0.23, 0.40) | 0.83 (0.79, 0.87) |

| Current risky use | ||||||

| Alcohol | 88 (19.2) | 86.4 (77.4, 92.8) | 78.7 (74.2, 82.8) | 4.1 (3.3, 5.0) | 0.17 (0.10, 0.29) | 0.83 (0.78, 0.87) |

| Drugs | 73 (15.9) | 72.6 (60.9, 82.4) | 86.0 (82.1, 89.3) | 5.2 (3.9, 6.9) | 0.32 (0.22, 0.46) | 0.79 (0.74, 0.85) |

| Problem use | ||||||

| Alcohol | 74 (16.1) | 87.8 (78.2, 94.3) | 76.6 (72.1, 80.8) | 3.8 (3.1, 4.6) | 0.16 (0.09, 0.29) | 0.82 (0.78, 0.87) |

| Drugs1 | 65 (14.2) | 84.6 (73.5, 92.4) | 87.0 (83.3, 90.2) | 6.5 (4.9, 8.6) | 0.18 (0.10, 0.31) | 0.86 (0.81, 0.91) |

| Substance use disorder | ||||||

| Alcohol | 60 (13.1) | 86.7 (75.4, 94.1) | 74.2 (69.6, 78.4) | 3.4 (2.8, 4.1) | 0.18 (0.09, 0.34) | 0.80 (0.76, 0.85) |

| Drugs | 74 (16.1) | 85.1 (75.0, 92.3) | 88.6 (85.0, 91.6) | 7.5 (5.6, 10.0) | 0.17 (0.10, 0.29) | 0.87 (0.83, 0.91) |

1Two cases missing due to incomplete Short Inventory of Problems for Drugs (SIP-D)

Because the SISQ-drug screens conjointly for both illicit and non-medical prescription drug use, we examined whether its sensitivity would differ among those who used prescription drugs only or illicit drugs only. Past-year illicit drug use without prescription drug use was reported by 90 participants, 64 of whom (71 %) screened positive on the SISQ-drug, while past-year prescription drug use without illicit use was reported by 3 participants, 2 of whom (67 %) screened positive on the SISQ-drug.

Among those who participated in saliva testing for drugs, which was offered at Site B, 8 participants tested positive for at least one drug. Each of these participants also reported unhealthy drug use on the self-reported reference standard measures.

Subgroup Analyses

Analyses of the sensitivity and specificity of the SISQs for specific subgroups are presented in Table 5. The only statistically significant differences were reduced sensitivity of the SISQ for detecting unhealthy drug use among non-native English speakers (sensitivity 46.2 versus 74.3 %) and among those with less than a high school education or GED (sensitivity 63.3 versus 79.0 %).

Table 5.

Sensitivity, Specificity, and Area Under the Curve (AUC) of the SISQs Compared to Reference Standard Measures for Unhealthy Alcohol and Drug Use in Select Subgroups (N = 459). (Statistically significant differences between subgroups are in bold text)

| Any unhealthy use | N | Sensitivity % (95 % CI) | Specificity % (95 % CI) | AUC (95 % CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alcohol | ||||

| Female | 236 | 75.0 (60.4, 86.4) | 83.0 (76.8, 88.1) | 0.79 (0.72, 0.86) |

| Male | 223 | 72.4 (62.5, 81.0) | 87.2 (80.0, 92.5) | 0.80 (0.75, 0.85) |

| Age 21–50 | 267 | 75.0 (65.1, 83.3) | 84.2 (77.9, 89.3) | 0.80 (0.75, 0.85) |

| Age 51–65 | 192 | 70.0 (55.4, 82.1) | 85.2 (78.3, 90.6) | 0.78 (0.71, 0.85) |

| Hispanic | 93 | 80.8 (60.6, 93.4) | 80.6 (69.1, 89.2) | 0.81 (0.72, 0.90) |

| Non-Hispanic | 364 | 71.7 (62.7, 79.5) | 85.7 (80.6, 89.8) | 0.79 (0.74, 0.83) |

| English primary language | 359 | 73.2 (64.4, 80.8) | 84.7 (79.5, 89.1) | 0.79 (0.74, 0.84) |

| Non-English primary language | 100 | 73.9 (51.6, 89.8) | 84.4 (74.4, 91.7) | 0.79 (0.69, 0.89) |

| Born in US | 296 | 74.1 (65.0, 81.9) | 85.3 (79.4, 90.1) | 0.80 (0.75, 0.85) |

| Born outside US | 163 | 70.6 (52.5, 84.9) | 83.7 (76.2, 89.6) | 0.77 (0.69, 0.86) |

| Education or health literacy < high school level | 209 | 69.9 (58.0, 80.1) | 84.6 (77.4, 90.2) | 0.77 (0.71, 0.83) |

| Education or health literacy ≥ high school level | 250 | 76.7 (65.4, 85.8) | 84.7 (78.6, 89.7) | 0.81 (0.75, 0.86) |

| Drug | ||||

| Female | 236 | 65.9 (49.4, 79.9) | 94.4 (90.1, 97.2) | 0.80 (0.73, 0.88) |

| Male | 221 | 74.1 (63.1, 83.2) | 94.3 (89.1, 97.5) | 0.84 (0.79, 0.89) |

| Age 21–50 | 266 | 75.6 (65.1, 84.2) | 93.9 (89.3, 96.9) | 0.85 (0.80, 0.90) |

| Age 51–65 | 191 | 61.1 (43.5, 76.9) | 94.8 (90.1, 97.7) | 0.78 (0.70, 0.86) |

| Hispanic | 93 | 60.9 (38.5, 80.3) | 95.7 (88.0, 99.1) | 0.78 (0.68, 0.89) |

| Non-Hispanic | 362 | 73.7 (63.9, 82.1) | 93.9 (90.3, 96.5) | 0.84 (0.79, 0.88) |

| English primary language | 357 | 74.3 (65.1, 82.2) a | 94.4 (90.7, 96.9) | 0.84 (0.80, 0.89) |

| Non-English primary language | 100 | 46.2 (19.2, 74.9) a | 94.3 (87.1, 98.1) | 0.70 (0.56, 0.85) |

| Born in U.S. | 294 | 73.0 (63.2, 81.4) | 94.3 (90.1, 97.1) | 0.84 (0.79, 0.88) |

| Born outside U.S. | 163 | 63.6 (40.7, 82.8) | 94.3 (89.1, 97.5) | 0.79 (0.69, 0.89) |

| Education or health literacy < high school level | 209 | 63.3 (49.9, 75.4) a | 93.3 (88.0, 96.7) | 0.78 (0.72, 0.85) |

| Education or health literacy ≥ high school level | 248 | 79.0 (66.8, 88.3) a | 95.2 (91.0, 97.8) | 0.87 (0.82, 0.92) |

aDifference between groups was statistically significant (p < 0.01)

Feasibility

A majority (71 %) of participants were able to complete the SISQs without assistance. At Site A, most requests for assistance (27/44, 61 %) were because of difficulty reading or comprehending the SISQs; 9 (29 %) were for problems using the computer, and 8 (18 %) were for other types of assistance. At Site B, most requests (68/88, 77 %) were for problems using the computer, almost all due to confusion about how to advance to the next question. At Site B, 10 (11 %) participants had problems reading or comprehending the questions, and 10 (11 %) requested other types of assistance. The SISQs had higher sensitivity and lower specificity for detecting unhealthy use among participants who did not request assistance. With respect to alcohol, sensitivity was 77.5 % (95 % CI 68.6–84.9) and specificity was 81.9 % (95 % CI 76.2–86.8) in those who did not request assistance, while sensitivity was 60.0 % (95 % CI 42.1–76.1) and specificity was 90.7 % (95 % CI 83.1–95.7) in those who did. For drugs, a similar pattern was observed: sensitivity was 76.3 % (95 % CI 66.4–84.5) and specificity was 93.6 % (95 % CI 89.6–96.4) in those who did not request assistance, and sensitivity was 55.2 % (95 % CI 35.7–73.6) and specificity 96.1 % (95 % CI 90.3–98.9) in those who did.

DISCUSSION

The self-administered alcohol and drug SISQs each had adequate sensitivity and high specificity for the detection of unhealthy substance use in this sample of adult primary care patients. While the self-administered SISQs did not have the very high sensitivity and specificity observed for the interviewer-administered versions,22,23 the modest decrement in accuracy must be weighed against the potential advantages of a self-administered approach. These advantages include the ability to accomplish screening prior to the medical encounter, maintaining fidelity even when used outside of a tightly controlled research setting,25 and the more open disclosure of stigmatized behaviors that is achieved with self-administered questionnaires.30,31,51–53

The differences in performance of the self-administered versus interviewer-administered SISQs could also be driven by differences in study populations. The interviewer-administered SISQs were validated in a single site,22,23 while the current study drew from two geographically distinct primary care clinics, serving populations with varied demographic and substance use characteristics.

All brief substance use screening tools have accuracy limitations, and their performance can vary depending on the population and the context in which they are administered. The SISQs have similar sensitivity and specificity to those of other commonly used screening tools, such as the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test consumption items (AUDIT-C)22,54,55 and the Drug Abuse Screening Test (DAST-10),23,56 both of which are significantly longer and relied on a trained interviewer to deliver them in the validation studies.

The accuracy of computer self-administered SISQs might be improved by modifying their delivery to improve comprehension and usability. Many participants requested some assistance in completing the SISQs, and sensitivity was substantially lower in these individuals. Still others may have had difficulty understanding the questions, but did not ask for assistance. It is possible that modifying the self-administered SISQs by providing structured response categories, simplifying the language, and providing definitions of terms, or by using an audio computer-assisted self-interview (ACASI) approach to accommodate those with lower literacy, could improve their accuracy.

Most of the assistance requests were from Site B, and almost all were due to participants having to touch a “Next question” button to advance to the next item. At Site A, a brief tutorial that participants viewed on the computer prior to answering the SISQs likely mitigated this problem. While this type of technical issue could pose a threat to the feasibility of integrating computer self-administered screening in routine care, it may be avoided through simple modifications of the user interface and usability testing prior to implementation.

Brief screening tools like the self-administered SISQs may need to be followed by further assessment to guide clinical interventions. Assessment would be required to identify what substances (other than alcohol) a patient was using, and may be needed to distinguish between individuals with risky or problem use versus dependence. While the interviewer-administered SISQs appear to discriminate between unhealthy use and dependence with good precision by applying different cutoffs,24 further analysis of self-administered SISQs is needed to determine whether these cutoffs can be similarly applied.

Limitations

Our study does have limitations. Both samples were drawn from East Coast safety-net hospital-based primary care clinics, and thus our findings may not fully generalize to other populations. We do not know, for example, how the self-administered SISQs would perform in non-urban settings or in populations with a lower prevalence of illicit drug use. While we would anticipate comprehension of the SISQs to be easier for primary care populations with higher levels of formal education and fewer non-native English speakers, there could be unforeseen problems with their feasibility or acceptability. Similarly, individuals over the age of 65, who may differ in their responses to computer self-administered screening tools or may find them more challenging to operate, were excluded from our study. Many patients were ineligible for the study due to lack of English fluency, indicating that having SISQs available in other languages would be important for their adoption in clinical practice.

We tested only computer self-administered versions of the SISQs, and cannot anticipate how results might differ if they were administered on paper. However, the format of the questions was identical to what would be given in a paper-based version. A limitation of our study design was the lack of biological measures at Site A and the use of only saliva testing at Site B. However, the accuracy of the SISQs was supported by the biological measures that were collected, which detected no cases of drug misuse that were not already reported on the self-reported reference standard instruments.

Perhaps the most important limitation of our findings is that the SISQs were administered anonymously and with an assurance of confidentiality. We do not know how our findings would have been influenced had participants been informed that their medical provider or other clinic staff would receive their results. This is an important area of future research for screening tools like the SISQs, which are intended for use in clinical practice.

CONCLUSIONS

The use of computer self-administered SISQs is a valid approach for detecting unhealthy alcohol and drug use in adult primary care patients. Although interviewer-administered substance use screening tools may have greater accuracy in a research context, in real-world practice settings there can be distinct advantages to using a self-administered approach. The computer self-administered SISQs may facilitate routine screening for substance use in primary care.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Contributors

Seville Meli, Jacqueline German, Ritika Batajoo, Catherine Federowicz, Marshall Gillette, Charlie Jose, Emily Maple, Keshia Toussaint, Arianne Ramautar, Derek Nelsen, Linnea Russell, Naeun Park, Elizabeth Stevens, Andrew Wallach, Barbara Porter, Valerie Perel, and Marc N. Gourevitch.

Funders

NIDA K23 DA030395; NIH/NCATS UL1 TR000038; P30 DA011041. Additional funding was by subcontract from The MITRE Corporation, who were contracted by the White House Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology and the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. The manuscript does not necessarily reflect the views of NIH/NIDA, The MITRE Corporation, the ONC, or SAMHSA.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Maciosek MV, Coffield AB, Edwards NM, Flottemesch TJ, Goodman MJ, Solberg LI. Priorities among effective clinical preventive services: results of a systematic review and analysis. Am J Prev Med. 2006;31(1):52–61. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2006.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moyer VA. Screening and behavioral counseling interventions in primary care to reduce alcohol misuse: U.S. preventive services task force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2013;159(3):210–218. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-159-3-201308060-00652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Solberg LI, Maciosek MV, Edwards NM. Primary care intervention to reduce alcohol misuse ranking its health impact and cost effectiveness. Am J Prev Med. 2008;34(2):143–152. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.09.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Whitlock EP, Polen MR, Green CA, Orleans T, Klein J. Behavioral counseling interventions in primary care to reduce risky/harmful alcohol use by adults: a summary of the evidence for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2004;140(7):557–568. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-140-7-200404060-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA). About SBIRT. Available from: http://www.samhsa.gov/sbirt/about. Accessed 2015 March 30.

- 6.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) In: A guide to substance abuse services for primary care clinicians. Center for Substance Abuse Treatment, editor. Rockville: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 1997. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA). Screening for Drug Use in Medical Settings: National Institutes of Health; 2010. Available from: http://www.webcitation.org/6WjPYIB76. Accessed 2015 March 30.

- 8.Roy-Byrne P, Bumgardner K, Krupski A, Dunn C, Ries R, Donovan D, et al. Brief intervention for problem drug use in safety-net primary care settings a randomized clinical trial. JAMA-J Am Med Assoc. 2014;312(5):492–501. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.7860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Saitz R, Palfai TPA, Cheng DM, Alford DP, Bernstein JA, Lloyd-Travaglini CA, et al. Screening and brief intervention for drug use in primary care the ASPIRE randomized clinical trial. JAMA-J Am Med Assoc. 2014;312(5):502–513. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.7862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Saitz R, Alford DP, Bernstein J, Cheng DM, Samet J, Palfai T. Screening and brief intervention for unhealthy drug use in primary care settings: randomized clinical trials are needed. J Addict Med. 2010;4(3):123–130. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0b013e3181db6b67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for Illicit Drug Use: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. 2008. Available from: http://www.webcitation.org/6WjMUXPGw. Accessed 2015 March 30.

- 12.Danaei G, Ding EL, Mozaffarian D, Taylor B, Rehm J, Murray CJ, et al. The preventable causes of death in the United States: comparative risk assessment of dietary, lifestyle, and metabolic risk factors. PLoS Med. 2009;6(4):e1000058. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Antoniou T, Tseng AL. Interactions between recreational drugs and antiretroviral agents. Ann Pharmacother. 2002;36(10):1598–1613. doi: 10.1345/aph.1A447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lindsey WT, Stewart D, Childress D. Drug interactions between common illicit drugs and prescription therapies. Am J Drug Alcohol Abus. 2012;38(4):334–343. doi: 10.3109/00952990.2011.643997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Malta M, Strathdee SA, Magnanini MM, Bastos FI. Adherence to antiretroviral therapy for human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immune deficiency syndrome among drug users: a systematic review. Addiction. 2008;103(8):1242–1257. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02269.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Arnsten JH, Demas PA, Grant RW, Gourevitch MN, Farzadegan H, Howard AA, et al. Impact of active drug use on antiretroviral therapy adherence and viral suppression in HIV-infected drug users. J Gen Intern Med. 2002;17(5):377–381. doi: 10.1007/s11606-002-0044-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Unintentional poisoning deaths–United States, 1999–2004. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2007;56(5):93–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Baumeister SE, Gelberg L, Leake BD, Yacenda-Murphy J, Vahidi M, Andersen RM. Effect of a primary care based brief intervention trial among risky drug users on health-related quality of life. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2014;142:254–261. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2014.06.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Williams EC, Johnson ML, Lapham GT, Caldeiro RM, Chew L, Fletcher GS, et al. Strategies to implement alcohol screening and brief intervention in primary care settings: a structured literature review. Psychol Addict Behav: J Soc Psychol Addicti Behav. 2011;25(2):206–214. doi: 10.1037/a0022102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kaner E. Brief alcohol intervention: time for translational research. Addiction. 2010;105(6):960–961. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02848.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nilsen P. Brief alcohol intervention–where to from here? Challenges remain for research and practice. Addiction. 2010;105(6):954–959. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02779.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Smith PC, Schmidt SM, Allensworth-Davies D, Saitz R. Primary care validation of a single-question alcohol screening test. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24(7):783–788. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-0928-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Smith PC, Schmidt SM, Allensworth-Davies D, Saitz R. A single-question screening test for drug use in primary care. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170(13):1155–1160. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Saitz R, Cheng DM, Allensworth-Davies D, Winter MR, Smith PC. The ability of single screening questions for unhealthy alcohol and other drug use to identify substance dependence in primary care. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2014;75(1):153–157. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2014.75.153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bradley KA, Lapham GT, Hawkins EJ, Achtmeyer CE, Williams EC, Thomas RM, et al. Quality concerns with routine alcohol screening in VA clinical settings. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26(3):299–306. doi: 10.1007/s11606-010-1509-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Williams EC, Achtmeyer CE, Thomas RM, Grossbard JR, Lapham GT, Chavez LJ, et al. Factors underlying quality problems with alcohol screening prompted by a clinical reminder in primary care: A multi-site qualitative study. J Gen Intern Med. 2015 doi:10.1007/s11606-015-3248-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.Johnson M, Jackson R, Guillaume L, Meier P, Goyder E. Barriers and facilitators to implementing screening and brief intervention for alcohol misuse: a systematic review of qualitative evidence. J Publ Health (Oxf) 2011;33(3):412–421. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdq095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sterling S, Kline-Simon AH, Wibbelsman C, Wong A, Weisner C. Screening for adolescent alcohol and drug use in pediatric health-care settings: predictors and implications for practice and policy. Addict Sci Clin Pract. 2012;7(1):13. doi: 10.1186/1940-0640-7-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Spear SS, M, Gilberti B, Fiellin M, McNeely J. Usability and acceptability of an audio guided computer-assisted self-interview (ACASI) version of the Alcohol, Smoking, and Substance Involvement Screening Test. Presented at Addiction Health Services Research Conference 2013.

- 30.Tourangeau R, Smith TW. Asking sensitive questions - the impact of data collection mode, question format, and question context. Publ Opin Q. 1996;60(2):275–304. doi: 10.1086/297751. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wight RG, Rotheram-Borus MJ, Klosinski L, Ramos B, Calabro M, Smith R. Screening for transmission behaviors among HIV-infected adults. Aids Educ Prev. 2000;12(5):431–441. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Results from the 2012 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Summary of National Findings. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2013 NSDUH Series H-46, HHS Publication No.(SMA) 13–4795.

- 33.Lee JD, Delbanco B, Wu E, Gourevitch MN. Substance use prevalence and screening instrument comparisons in urban primary care. Subst Abus: Off Publ Assoc Med Educ Res Subst Abus. 2011;32(3):128–134. doi: 10.1080/08897077.2011.562732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Arozullah AM, Yarnold PR, Bennett CL, Soltysik RC, Wolf MS, Ferreira RM, et al. Development and validation of a short-form, rapid estimate of adult literacy in medicine. Med Care. 2007;45(11):1026–1033. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3180616c1b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Alonzo TA, Pepe MS. Using a combination of reference tests to assess the accuracy of a new diagnostic test. Stat Med. 1999;18(22):2987–3003. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0258(19991130)18:22<2987::AID-SIM205>3.0.CO;2-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sobell LC, Sobell MB. Timeline follow-back. Measuring alcohol consumption. New York: Springer; 1992. pp. 41–72. [Google Scholar]

- 37.National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA). Helping patients who drink too much: a clinician’s guide, 2005 ed.: NIAAA; 2007. Available from: http://pubs.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/Practitioner/CliniciansGuide2005/guide.pdf. Accessed 2015 March 30.

- 38.Cooke F, Bullen C, Whittaker R, McRobbie H, Chen MH, Walker N. Diagnostic accuracy of NicAlert cotinine test strips in saliva for verifying smoking status. Nicotine Tob Res: Off J Soc Res Nicotine Tob. 2008;10(4):607–612. doi: 10.1080/14622200801978680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Heltsley R, DePriest A, Black DL, Robert T, Marshall L, Meadors VM, et al. Oral fluid drug testing of chronic pain patients. I. Positive prevalence rates of licit and illicit drugs. J Anal Toxicol. 2011;35(8):529–540. doi: 10.1093/anatox/35.8.529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cone EJ, Presley L, Lehrer M, Seiter W, Smith M, Kardos KW, et al. Oral fluid testing for drugs of abuse: positive prevalence rates by Intercept immunoassay screening and GC-MS-MS confirmation and suggested cutoff concentrations. J Anal Toxicol. 2002;26(8):541–546. doi: 10.1093/jat/26.8.541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lecrubier Y, Sheehan D, Weiller E, Amorim P, Bonora I, Harnett Sheehan K, et al. The Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI). A short diagnostic structured interview: reliability and validity according to the CIDI. Eur Psychiatr. 1997;12(5):224–231. doi: 10.1016/S0924-9338(97)83296-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH, Amorim P, Janavs J, Weiller E, et al. The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.): the development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. J Clin Psychiatr. 1998;59(Suppl 20):22–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Allensworth-Davies D, Cheng DM, Smith PC, Samet JH, Saitz R. The Short Inventory of Problems-Modified for Drug Use (SIP-DU): validity in a primary care sample. Am J Addict/Am Acad Psychiatr Alcohol Addict. 2012;21(3):257–262. doi: 10.1111/j.1521-0391.2012.00223.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Feinn R, Tennen H, Kranzler HR. Psychometric properties of the short index of problems as a measure of recent alcohol-related problems. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2003;27(9):1436–1441. doi: 10.1097/01.ALC.0000087582.44674.AF. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Simel DL, Samsa GP, Matchar DB. Likelihood ratios with confidence: sample size estimation for diagnostic test studies. J Clin Epidemiol. 1991;44(8):763–770. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(91)90128-V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Satre D, Wolfe W, Eisendrath S, Weisner C. Computerized screening for alcohol and drug use among adults seeking outpatient psychiatric services. Psychiatr Serv. 2008;59(4):441–444. doi: 10.1176/ps.2008.59.4.441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Butler SFCE, Bromberg JI, Budman SH, Buono DP. Computer-assisted screening and intervention for alcohol problems in primary care. J Technol Hum Serv. 2003;21(3):1–19. doi: 10.1300/J017v21n03_01. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Reichmann WM, Losina E, Seage GR, Arbelaez C, Safren SA, Katz JN, et al. Does modality of survey administration impact data quality: audio computer assisted self interview (ACASI) versus self-administered pen and paper? PLoS One. 2010;5(1):e8728. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Seed P. DIAGT: Stata module to report summary statistics for diagnostic tests compared to true disease status 2010. Available from: http://EconPapers.repec.org/RePEc:boc:bocode:s423401. Accessed 2015 March 30.

- 50.Hanley JA, McNeil BJ. The meaning and use of the area under a receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve. Radiology. 1982;143(1):29–36. doi: 10.1148/radiology.143.1.7063747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Newman JC, Des Jarlais DC, Turner CF, Gribble J, Cooley P, Paone D. The differential effects of face-to-face and computer interview modes. Am J Public Health. 2002;92(2):294–297. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.92.2.294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rogers SM, Willis G, Al-Tayyib A, Villarroel MA, Turner CF, Ganapathi L, et al. Audio computer assisted interviewing to measure HIV risk behaviours in a clinic population. Sex Transm Infect. 2005;81(6):501–507. doi: 10.1136/sti.2004.014266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Turner CF, Al-Tayyib A, Rogers SM, Eggleston E, Villarroel MA, Roman AM, et al. Improving epidemiological surveys of sexual behaviour conducted by telephone. Int J Epidemiol. 2009;38(4):1118–1127. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyp210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Reinert DF, Allen JP. The alcohol use disorders identification test: an update of research findings. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2007;31(2):185–199. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2006.00295.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bradley KA, Bush KR, Epler AJ, Dobie DJ, Davis TM, Sporleder JL, et al. Two brief alcohol-screening tests From the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT): validation in a female Veterans Affairs patient population. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163(7):821–829. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.7.821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Grekin ER, Svikis DS, Lam P, Connors V, Lebreton JM, Streiner DL, et al. Drug use during pregnancy: validating the Drug Abuse Screening Test against physiological measures. Psychol Addict Behav: J Soc Psychol Addict Behav. 2010;24(4):719–723. doi: 10.1037/a0021741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]