Abstract

Objectives

To estimate the cost-effectiveness of ranolazine when added to standard-of-care (SoC) antianginals compared with SoC alone in patients with stable coronary disease experiencing ≥3 attacks/week.

Setting

An economic model utilising a UK health system perspective, a 1-month cycle-length and a 1-year time horizon.

Participants

Patients with stable coronary disease experiencing ≥3 attacks/week starting in 1 of 4 angina frequency health states based on Seattle Angina Questionnaire Angina Frequency (SAQAF) scores (100=no; 61–99=monthly; 31–60=weekly; 0–30=daily angina).

Intervention

Ranolazine added to SoC or SoC alone. Patients were allowed to transition between SAQAF states (first cycle only) or death (any cycle) based on probabilities derived from the randomised, controlled Efficacy of Ranolazine in Chronic Angina trial and other studies. Patients not responding to ranolazine in month 1 (not improving ≥1 SAQAF health state) discontinued ranolazine and were assumed to behave like SoC patients.

Primary and secondary outcomes measures

Costs (£2014) and quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) for patients receiving and not receiving ranolazine.

Results

Ranolazine patients lived a mean of 0.701 QALYs at a cost of £5208. Those not receiving ranolazine lived 0.662 QALYs at a cost of £5318. The addition of ranolazine to SoC was therefore a dominant economic strategy. The incremental cost-effectiveness ratio was sensitive to ranolazine cost; exceeding £20 000/QALY when ranolazine's cost was >£203/month. Ranolazine remained a dominant strategy when indirect costs were included and mortality rates were assumed to increase with worsening severity of SAQAF health states. Monte Carlo simulation found ranolazine to be a dominant strategy in ∼71% of 10 000 iterations.

Conclusions

Although UK-specific data on ranolazine's efficacy and safety are lacking, our analysis suggest ranolazine added to SoC in patients with weekly or daily angina is likely cost-effective from a UK health system perspective.

Keywords: CARDIOLOGY, HEALTH ECONOMICS

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the first economic modelling study of ranolazine from the UK perspective.

The model utilised data from the randomised and controlled Efficacy of Ranolazine in Chronic Angina (ERICA) trial.

As a simplifying assumption, angina states were assumed not to change after the first month.

It is unclear whether our findings are generalisable to patients with less frequent angina symptoms.

Results of the short duration ERICA trial were extrapolated to a 1-year time horizon.

The prevalence of stable angina in the UK is about 2.1 million people.1 Stable angina is associated with an unfavourable impact on health-related quality-of-life (HrQoL),2 3 morbidity and mortality4 and economic outcomes (increased direct and lost productivity costs);5 6 with afflicted patients reporting their health to be twice as poor as those who previously suffered a stroke, and direct treatment costs of at least £700 million per year.7

Ranolazine is indicated in the UK for the treatment of chronic stable angina and the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) endorses its use in persons with stable angina who cannot tolerate or have contraindications to the first-line therapies of β-blockers or calcium channel blockers, or for persons whom symptoms are not controlled after optimal use of β-blockers and calcium channel blockers.8 The Combination Assessment of Ranolazine In Stable Angina (CARISA),9 Efficacy of Ranolazine in Chronic Angina (ERICA)10 and Type 2 Diabetes Evaluation of Ranolazine in Subjects With Chronic Stable Angina (TERISA)11 randomised controlled trials demonstrated ranolazine's ability to significantly reduce weekly angina frequency by 0.4–1.2 attacks when added to standard-of-care (SoC) antianginal therapies, as well as, reduce sublingual nitroglycerin consumption. Moreover, in TERISA, ranolazine was found to significantly improve HrQoL of patient with stable angina, as evidence by an improvement in the physical component subscore of the Short-Form-36.11

Here we report the results of a cost-effectiveness analysis from a UK perspective to estimate the costs, quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) and incremental cost-effectiveness of ranolazine when added to SoC antianginal therapy compared with SoC antianginal therapy alone in patients with stable coronary disease experiencing frequent angina attacks.

Methods

We followed the Consolidated Health Economic Evaluation Reporting Standards (CHEERS) statement in reporting this cost-effectiveness analysis.12

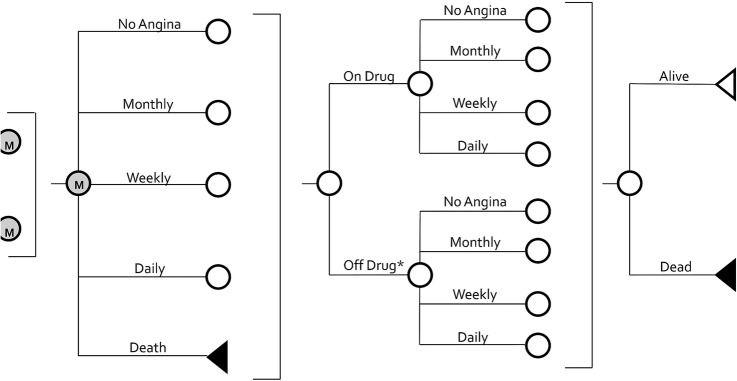

This economic decision model utilised a 1-year time horizon, a cycle length of 1 month and was performed from the UK health system perspective. It included five mutually exclusive health states; four related to angina frequency (no, monthly, weekly and daily angina symptoms) and the absorbing health state of death (figure 1). This model was built using efficacy and tolerability data from the ERICA trial;10 a randomised controlled trial of 565 patients with stable coronary artery disease experiencing ≥3 angina attacks/week (ie, 5.6±0.18 episodes/week and consuming 4.7±0.21 nitroglycerin tablets/week) assigned to receive ranolazine (500 mg twice daily for the first week followed by 1000 mg twice daily thereafter) or placebo in addition to SoC antianginal therapy (including a maximal dose of amlodipine in all patients, 45% and 52% long-acting nitrate and ACE inhibitor use, and no β-blocker use). As observed in ERICA, patients entering the model started in 1 of 3 of the 4 angina frequency health states (no patients started in the ‘no angina’ state) based on Seattle Angina Questionnaire Angina Frequency (SAQAF) domain scores.13 Patients scoring 100 points on the SAQAF were deemed to have no angina symptoms, whereas scores of 61–99, 31–60 and 0–30 represented monthly, weekly and daily angina symptoms, respectively.14 We utilised the SAQAF to define our model's health states because it was an important patient-reported outcome measure utilised in the ERICA trial10 and has been used in other angina clinical trials9 11 and prior stable angina epidemiological and cost-of-illness analyses.2–5 13

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the economic decision model. The model was used to determine separately the total cost of treatment accrued and quality-adjusted life-years lived by the patients with stable angina receiving and not receiving ranolazine. Regardless of treatment assignment, patients entered the model in one of three angina frequency health states based on SAQAF scores (100=no; 61–99=monthly; 31–60=weekly; 0–30=daily angina; no patients started in ‘no’ angina) and were allowed to transition between states in the first month based on treatment-specific probabilities derived from the Efficacy of Ranolazine in Chronic Angina trial and other studies. Patients not responding to ranolazine in month 1 (ie, not improving ≥1 SAQAF health state) or experiencing an adverse event requiring discontinuation were assumed to stop taking ranolazine and behave like SoC (plus placebo) patients. Only patients assigned to receive ranolazine at the initiation of the model could discontinue therapy (for lack of efficacy or adverse drug events) and discontinuation could only occur during the first cycle. Patients randomised to SoC (plus placebo) started and had to remain ‘off drug’. In the 2nd through 12th month, all patients were assumed to stay in the same angina frequency health state for the remainder of the model's time horizon or until death. Transition to death could occur during any cycle. M, Markov node; SAQAF, Seattle Angina Questionnaire Angina Frequency; SoC, standard-of-care.

Patients transitioned between the four aforementioned angina frequency health states and the death state during the first cycle. After this, patients were assumed to remain in the same health state, apart from those who died. The model's first set of 12, 1-month cycle-length transition probabilities were calculated directly from the ERICA trial using individual patient data.10 Transition probabilities for ranolazine patients achieving adequate efficacy on treatment, defined as improving by at least one angina frequency health state (eg, transitioning from daily to weekly angina symptoms) were calculated based on rates observed in corresponding ERICA patients (table 1). For patients not receiving ranolazine, the probability of moving from one angina frequency health state to another was calculated based on those observed in the SoC arm of the ERICA trial (table 2).

Table 1.

Transition probability matrix for ranolazine responders during the first cycle

| SAQAF EOT classification |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | Monthly | Weekly | Daily | |

| SAQAF baseline classification | ||||

| No | – | – | – | – |

| Monthly | 2/2 (100%) 95% CI (34% to 100%) |

– | – | – |

| Weekly | 13/95 (13.7%) 95% CI (8% to 22%) |

82/95 (86.3%) 95% CI (78% to 92%) |

– | – |

| Daily | 2/47 (4.3%) 95% CI (1% to 14%) |

10/47 (21.3%) 95% CI (12% to 35%) |

35/47 (74.5%) 95% CI (60% to 85%) |

– |

The SAQAF Domain category ranolazine responders started in are depicted on the vertical axis (100=no, 61–99=monthly, 31–60=weekly and 0–30=daily symptoms) and the category they finished the double-blind trial period in is depicted on the horizontal axis. For example, 47 ranolazine responders began the study reporting ‘daily’ angina symptoms and 0 (0%), 35 (74.5%), 10 (21.3%) and 2 (4.3%) of these same patients reported having daily, weekly, monthly and no angina symptoms at the end of the trial.

EOT, end-of-treatment; SAQAF, Seattle Angina Questionnaire Angina Frequency.

Table 2.

Transition probability matrix for standard-of-care (plus placebo) during the first cycle

| SAQAF EOT classification |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | Monthly | Weekly | Daily | |

| SAQAF baseline classification | ||||

| No | – | – | – | – |

| Monthly | 1/20 (5.0%) 95% CI (0.9% to 24%) |

17/20 (85.0%) 95% CI (64% to 95%) |

2/20 (10.0%) 95% CI (3.0% to 30%) |

0/20 (0%) 95% CI (0% to 16%) |

| Weekly | 8/193 (4.1%) 95% CI (2% to 8%) |

65/193 (33.7%) 95% CI (27% to 41%) |

112/193 (58.0%) 95% CI (51% to 65%) |

8/193 (4.1%) 95% CI (2% to 8%) |

| Daily | 2/68 (2.9%) 95% CI (0.8% to 10%) |

9/68 (13.2%) 95% CI (7% to 23%) |

33/68 (48.5%) 95% CI (37% to 60%) |

24/68 (35.3%) 95% CI (25% to 47%) |

The SAQAF Domain category standard-of-care patients started in are depicted on the vertical axis (100=no, 61–99=monthly, 31–60=weekly and 0–30=daily symptoms) and the category they finished the double-blind trial period in is depicted on the horizontal axis. For example, 68 standard-of-care patients began the study reporting ‘daily’ angina symptoms and 24 (35.3%), 33 (48.5%), 9 (13.2%) and 2 (2.9%) of these same patients reported having daily, weekly, monthly and no angina symptoms at the end of the trial.

EOT, end-of-treatment; SAQAF, Seattle Angina Questionnaire Angina Frequency.

Starting the second month (cycle 2) onwards, all patients were assumed to stay in the same angina frequency health state (no loss or additional efficacy in either treatment group could occur) for the remainder of the model's time horizon unless they died. During any cycle of the model, patients could transition to the death health state based on all-cause mortality rates in patients with angina (5.8%/year), derived from a prospective cohort study of patients with coronary artery disease from six Veterans Affairs General Internal Medicine Clinics.4

Patients receiving ranolazine could also discontinue treatment due to adverse drug reactions or lack of efficacy during, and only during, the first month of treatment. This assumption was based on the reasoning that patients reporting a lack of efficacy or adverse reactions requiring discontinuation of therapy would most likely do so in the first month10 11 and data from the TERISA trial11 suggesting the majority of the effect of ranolazine is seen in the first few weeks of treatment. The rates of ranolazine discontinuation due to adverse reactions and lack of efficacy were derived from the ERICA trial (table 3). Patients discontinuing ranolazine for any reason were assumed to follow the same pattern as SoC (plus placebo) patients.

Table 3.

Base-case variables and ranges used in sensitivity analysis

| Variable | Base-Case | Range | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| SAQAF classification definition | |||

| No | SAQAF=100 | NA | 6, 13 |

| Monthly | SAQAF=61–99 | NA | 6, 13 |

| Weekly | SAQAF=31–60 | NA | 6, 13 |

| Daily | SAQAF=0–30 | NA | 6, 13 |

| SAQAF classification at baseline | 6, 10 | ||

| No | 0% | NA | 6, 10 |

| Monthly | 6.1% | 100% | 6, 10 |

| Weekly | 71.0% | 100% | 6, 10 |

| Daily | 22.9% | 100% | 6, 10 |

| Definition of SAQAF responder | Improvement of ≥1 SAQAF classification | 20-point change in SAQAF | 5, 6 |

| Ranolazine non-response | 48% during first 4 weeks | 42.2–53.9% | 10 |

| Ranolazine discontinuation due to AE | 1.1% during first 4 weeks | 0.37–6% | 10 |

| All-cause mortality by angina frequency | |||

| No | 4.6% per year | 3.8–5.5% | 5 |

| Monthly | 4.8% per year | 3.8–6.1% | 5 |

| Weekly | 8.1% per year | 6.1–10.8% | 5 |

| Daily | 10.9% per year | 7.5–15.4% | 5 |

| All-cause mortality for all patients with angina | 5.8% per year | NA | 5 |

| Angina frequency utility (using EOT data) | 2, 10, 15 | ||

| No | 0.87 | 0.84–0.90 | 2, 10, 15 |

| Monthly | 0.76 | 0.75–0.77 | 2, 10, 15 |

| Weekly | 0.65 | 0.64–0.66 | 2, 10, 15 |

| Daily | 0.54 | 0.52–0.56 | 2, 10, 15 |

| Cost of ranolazine twice daily at any dose | £48.98/month | £24.49–£97.96 | 16 |

| Stable angina direct treatment costs/year (not including ranolazine) | 6 | ||

| No | £3529 | £3276–£3786 | 6 |

| Monthly | £4711 | £4255–£5023 | 6 |

| Weekly | £5493 | £4765–£6229 | 6 |

| Daily | £8374 | £6754–£9990 | 6 |

| Stable angina indirect costs/year | |||

| No | £2362 | £1011–£3373 | 7 |

| Monthly | £4012 | £2694–£5395 | 7 |

| Weekly | £4271 | £2694–£5395 | 7 |

| Daily | £8194 | £5395–£10 783 | 7 |

AE, adverse event; EOT, end-of-treatment; NA, not applicable; SAQAF, Seattle Angina Questionnaire Angina Frequency.

Our model determined the mean total cost of treatment accrued by the patient cohorts receiving and not receiving ranolazine separately, as well as the mean number of QALYs. This allowed for the calculation of incremental cost-effectiveness ratios (ICERs) defined as the difference in mean costs between the ranolazine plus SoC and SoC alone (plus placebo) patients divided by the difference in mean QALYs for each treatment. We also provide in this report an ICER defined as the difference in mean costs between the two groups divided by the difference in SAQAF response rate. Since the time horizon did not exceed 1 year, no discounting was performed. The model was programmed in TreeAge Pro V.2007 (TreeAge Software Inc, Williamstown, Massachusetts, USA).

We calculated QALYs by multiplying the time spent in each health state by corresponding EuroQol (EQ)-5D utilities estimates (scores between 1.0 and −0.564, on a scale where 1.0=perfect health and 0.0=death) for each angina frequency health state. EQ-5D utility scores were calculated by taking individual patient data from the ERICA trial and a applying them to a previously derived SAQ to UK EQ-5D mapping equation developed by Goldsmith et al.2 15

This cost-effectiveness analysis was performed from the UK health system perspective, and therefore, included only direct (inpatient, outpatient and drug) costs of treating stable angina. Direct medical costs were based on data from an economic substudy of the Metabolic Efficiency with Ranolazine for Less Ischemia in Non-ST Elevation Acute Coronary Syndrome (MERLIN)-TIMI 36 trial6 which assessed the association between angina frequency and subsequent cardiovascular resource utilisation among 5460 stable outpatients who completed the SAQ 4 months after experiencing an acute coronary syndrome and who were then followed for an additional 8 months. The monthly cost of both doses of ranolazine were set at published British National Formulary (BNF) pricing, and assumed to be the same for the 750 and 1000 mg doses.16 Since the CARISA trial9 suggested no clinically relevant difference in efficacy between the 750 and 1000 mg doses, we assumed the dose of ranolazine was titrated as in the ERICA trial even though the 1000 mg dose is not approved in the UK. All costs were inflated, when needed, using the Medical Care component of the Consumer Price Index17 and later expressed in 2014 British Sterling Pounds (£).

We performed one-way sensitivity analysis on all variables in table 3 over their a priori determined plausible ranges. In addition, we performed a number of scenario analyses to test whether: (1) assuming 100% of patients started the model in the daily and weekly angina frequency health states, (2) factoring in indirect costs, (3) allowing mortality rates to vary based on angina frequency health state severity, and (4) assuming not all patients failing to respond to ranolazine would discontinue therapy would impact the model's overall results and conclusions. We also performed an analysis changing the definition of response to ranolazine to a 20-point change in SAQAF (a previously determined threshold for a minimally important clinical improvement on the SAQAF domain).14

For our scenario analyses, lost productivity costs were derived from a published cost-of-illness study of patients with stable angina.6 This study calculated indirect costs, by estimating costs of lost productivity by those with stable angina, as well as all unpaid time devoted to caregiving by family members and friends. Mortality rates stratified by angina frequency published by Spertus et al4 were used to allow patients to transition to the death health state, conditional on SAQ angina frequency health state, but not treatment arm.

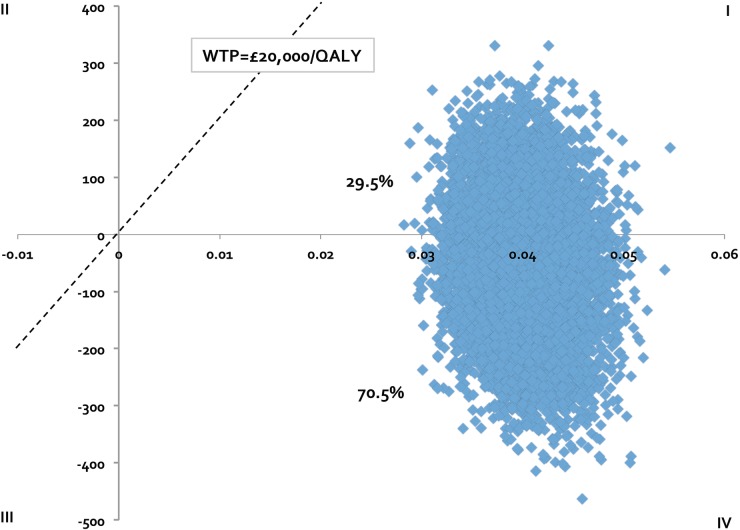

Finally, we performed a 10 000 iteration Monte Carlo simulation (MCS) to determine the joint uncertainty of model parameters. For each variable in MCS, we assumed a triangle distribution (defined by a likeliest, low and high value) since the true nature of variance for these variables is not well understood and the triangle distribution (when used appropriately) does not violate the requirements of any variable (ie, costs cannot be less than $0 and probabilities and utilities must lie between 0 and 1). The results of the MCS are provided as an incremental cost-effectiveness plane, with ICERs <£0 and £20 000/QALY gained considered economically dominant and cost-effective, respectively.

Results

Two hundred and seventy-seven participants (97% from Eastern Europe) receiving ranolazine in the ERICA trial were analysable, of whom 144 (52%) improved by at least 1 SAQAF classification during the 6-week double-blind trial period. Only 118 of 281 (42%) participants in the SoC only (plus placebo) group met the response definition (absolute difference in response rates=10%, 95% CI 2% to 18%). Patients improving at least 1 SAQAF classification (regardless of treatment) experienced a mean 32±14 point change in SAQAF score from baseline. Ranolazine patients lived a mean of 0.701 QALYs at a cost of £5208. Those not receiving ranolazine lived 0.662 QALYs and at a cost of £5318. Thus, the addition of ranolazine was shown to be a dominant economic strategy.

In performing one-way sensitivity analysis, the ICER was found sensitive to ranolazine cost; exceeding £20 000/QALY when the cost of ranolazine increased to >£203/month (table 4). On scenario analysis, ranolazine remained a dominant economic strategy when indirect costs were included in the model; when mortality rates were assumed to increase with worsening severity of SAQAF health states; or when both indirect costs and differences in mortality rates based on SAQAF were assumed. The model indicated that ranolazine would remain cost-effective, even if 100% of patients classified as non-responders continued on ranolazine past the first month (ICER=£4051/QALY). When the response to ranolazine was redefined to incorporate a 20-point change on the SAQAF score (in the base-case analysis, response was defined as improving by at least 1 SAQAF health state), the ICER was £1692/QALY. MCS found the addition of ranolazine cost-effective in >99% of 10 000 iterations assuming a £20 000/QALY willingness-to-pay threshold, and a dominant economic strategy in 70.5% of iterations run (figure 2).

Table 4.

Results of base-case, sensitivity and scenario analyses

| Sensitivity or scenario analysis | Treatment | Cost | QALY | ICER vs placebo |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Base-case | Ranolazine | £5208 | 0.701 | Ranolazine dominant |

| SoC+placebo | £5318 | 0.662 | – | |

| 100% daily | Ranolazine | £5915 | 0.639 | Ranolazine dominant |

| SoC+placebo | £6160 | 0.614 | – | |

| 100% weekly | Ranolazine | £5058 | 0.713 | Ranolazine dominant |

| SoC+placebo | £5109 | 0.672 | – | |

| Mortality differences assumed | Ranolazine | £5190 | 0.700 | Ranolazine dominant |

| SoC+placebo | £5272 | 0.659 | – | |

| Indirect costs included | Ranolazine | £9237 | 0.701 | Ranolazine dominant |

| SoC+placebo | £9725 | 0.662 | – | |

| Indirect costs included and mortality differences assumed | Ranolazine | £9203 | 0.700 | Ranolazine dominant |

| SoC+placebo | £9639 | 0.659 | – | |

| 20-point change | Ranolazine | £5362 | 0.688 | £1692/QALY |

| SoC+placebo | £5318 | 0.662 | – |

Results for the base-case and scenario analyses are depicted above. Incremental cost-effectiveness ratios were calculated as the difference in costs divided by the difference in QALYs between the two treatments. Ranolazine added to SoC therapy was considered cost-effective compared with SoC therapy alone when an incremental cost-effectiveness ratio was less than £20 000/QALY.

QALY, quality-adjusted life-year; SoC, standard-of-care.

Figure 2.

Incremental cost-effectiveness plane. Incremental cost-effectiveness plane based on 10 000 Monte Carlo simulation iterations, which drew parameters for each input simultaneously from probability distributions. Incremental cost (2014£) is on the vertical axis and incremental efficacy (quality-adjusted life-years, QALYs) is on the horizontal axis. As depicted on the incremental cost-effectiveness plane, the probability of ranolazine being cost-effective was >99% (quadrants II and III), assuming a willingness-to-pay (WTP) threshold of £20 000/QALY. We estimated there was a 70.5% chance the addition of ranolazine to standard-of-care therapy would be a dominant economic strategy compared with standard-of-care alone (quadrant III).

Discussion

The results of our economic analysis suggest that treatment of chronic stable angina with ranolazine is a dominant economic strategy when administered in addition to SoC antianginal in patients reporting daily or weekly angina symptoms. Importantly, our base-case analysis was built on the clinical assumption that patients who do not respond to ranolazine treatment (ie, continue to suffer the same degree of anginal symptoms) are taken off therapy and behave similarly to placebo patients. This responder-type analysis methodology has been utilised in other UK National Health Service/NICE cost-effectiveness models.18 19 Of note, our analysis indicates that from a UK perspective, discontinuing therapy in patients not adequately responding to therapy is not necessary to achieve cost-effectiveness.

Importantly, the definition of response used in our analysis (requiring a decrease in symptoms as measured by improving an entire angina frequency classification) is one that is easily translatable to clinical practice by simply questioning patients if their angina frequency is daily, weekly, monthly or absent. Nonetheless, alterative responder definitions merit consideration. One of the scenario analysis we performed utilised an alternative responder definition requiring a 20-point improvement in SAQAF score.14 Even with this more stringent definition of responder requiring a more robust benefit, the addition of ranolazine was still shown to be cost-effective with an ICER of £1692/QALY gained.

A small number of prior European economic analyses performed from the Spanish,20 Italian21 and Russian perspectives22 have also demonstrated the addition of ranolazine to SoC for the treatment of patients with chronic angina can be economically substantiated. Two of these analyses20 21 reported ICERs for ranolazine of ∼€8500/QALY gained; well below the €30 000/QALY gained willingness-to-pay threshold commonly referenced. The third, a Russian model,22 did not calculated cost/QALY gained but rather used change in angina frequency as its principal measure of effectiveness. This economic model estimated increased expenditures for medication in the ranolazine group, but reduced costs of emergency care and hospitalisations; resulting in a 20% decrease in the cost-effectives ratio for ranolazine added to SoC versus SoC alone (1641 RUB vs 1965 RUB, respectively). Our model described in this paper is novel and adds important information to the current body of literature. To our knowledge, this is the first report of the cost-effectiveness of ranolazine from the UK health system perspective, and our findings are supportive of NICE's current recommendation for ranolazine use in stable angina.8 Additionally, the aforementioned models20–22 used only direct medical costs, while our model (as a sensitivity analysis) included both direct and indirect costs. The addition of indirect costs to our model yielded an even larger gap (decrease) in treatment costs with the use of ranolazine compared with SOC alone (δ: £488 vs £110), substantiating the benefit of ranolazine from a societal perspective. Perhaps most importantly, our analysis is the only one to estimate transition probabilities and health utility scores using individual patient-level data from the randomised controlled ERICA trial.10 Access to this level of data likely increases the internal validity of our model by providing more accurate estimates of transition probabilities across SAQAF health states; as well as, allowing us to map UK EQ-5D equivalent health utility values (the EQ-5D being NICE's preferred health utility measure) needed for calculating QALYs.15 23

There are also limitations to consider when putting the results of our model into context. First, we needed to extrapolate the results of the 7-week double-blind treatment duration of the ERICA trial10 to a 1-year time horizon. Because the duration to which ranolazine will remain efficacious is unclear, we did not attempt to extend the model's time horizon out to longer than 1 year, and thus this model should be considered hypothesis generating. The fact that ∼85% of patients in the Ranolazine Open Label Experience (ROLE)24 remained on therapy and only 4.2% of 746 ranolazine-treated patients electively discontinued therapy at 1 year suggests our 1-year time horizon may be justifiable, as does longer term follow-up data from the MERLIN trial which shows stability in SAQAF, physical limitation and quality-of-life domain scores in patients with stable coronary disease over 12 months.6 14 25 Second, our analysis evaluated the cost-effectiveness of ranolazine in those suffering weekly or daily angina. Therefore, it is unclear whether our findings would be generalisable to patients with less frequent angina symptoms (eg, monthly). This being said, the TERISA trial11 did support ranolazine's efficacy in a population with a wider range of angina frequencies (an average weekly angina frequency between 1 and 28, and at least 1 angina episode/week). It is also important to note that we assumed UK patients as a group would have similar response to ranolazine as patients enrolled in the multinational ERICA trial. Unfortunately, data to test this assumption were not available in ERICA. Third, the dosage of ranolazine utilised in ERICA10 (500 mg twice daily for the first week followed by 1000 mg twice daily thereafter) differs from the approved dose in Europe (initial dose of 375 mg twice daily, titrated to 500 mg twice daily after 2–4 weeks, and based on patient response, further titrated to a maximum dose 750 mg twice daily).23 Importantly, data from the CARISA trial9 demonstrated greater improvements in exercise duration and reductions in angina attacks and nitroglycerin use compared with placebo with both the 750 mg (p≤0.03 for all end points) and 1000 mg (p≤0.03 for all end points) twice daily doses of ranolazine at 12 weeks; with no clinically relevant difference in efficacy between the 750 and 1000 mg doses. For this reason, using data from the 1000 mg twice daily arm of pivotal ERICA trial in this European model seems acceptable. Fourth, in the ERICA trial, β-blockers were not used to treat angina, and therefore we could not assess the cost-effectiveness of adding ranolazine to β-blocker therapy (which is often effective and inexpensive). Importantly, the TERISA trial provides data suggesting ranolazine remained efficacious when added to ∼90% β-blocker background therapy.11 Despite this, additional cost-effectiveness analyses based on TERISA data would be helpful in demonstrating ranolazine's cost-effectiveness in heavily β-blocker-treated population (as well as in a wider range of angina symptom frequencies and patients with diabetes). Finally, our model did not directly incorporate the impact of adverse drug reactions to ranolazine. These adverse events, however, are typically not serious (eg, usually limited to dizziness, nausea and constipation), and consequently are not likely to have any significant impact on costs or QALYs.10 11

Footnotes

Contributors: CIC, CGK and NF were involved in study concept and design, acquisition of data, and analysis and interpretation of data. CIC and CGK drafted the manuscript. CIC, CGK and NF were involved in critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. CIC and CGK provided administrative, technical or material support. CIC was involved in study supervision. CIC and CGK had full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. The authors meet criteria for authorship as recommended by the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICJME) and were fully responsible for all content and editorial decisions, and were involved in all stages of manuscript development.

Funding: This work was supported by Menarini International Operations, Luxembourg, SA, makers of ranolazine.

Competing interests: CIC has received grant funding and consultancy fees from Gilead Sciences Inc, Foster City, California, USA and Menarini International Operations, Luxembourg, SA. NF received grant funding from Menarini International Operations, Luxembourg, SA.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.British Heart Foundation. Coronary heart disease statistics 2010. https://www.bhf.org.uk/~/media/files/research/heart-statistics/hs2010_coronary_heart _disease_statistics.pdf (accessed 6 Mar 2015).

- 2.Goldsmith KA, Dyer MT, Buxton MJ et al. Mapping of the EQ-5D index from clinical outcome measures and demographic variables in patients with coronary heart disease. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2010;8:54 10.1186/1477-7525-8-54 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goldsmith KA, Dyer MT, Schofield PM et al. Relationship between the EQ-5D index and measures of clinical outcomes in selected studies of cardiovascular interventions. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2009;7:96 10.1186/1477-7525-7-96 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Spertus JA, Jones P, McDonell M et al. Health status predicts long-term outcome in outpatients with coronary disease. Circulation 2002;106:43–9. 10.1161/01.CIR.0000020688.24874.90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arnold SV, Morrow DA, Lei Y et al. Economic impact of angina after an acute coronary syndrome: insights from the MERLIN-TIMI 36 trial. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 2009;2:344–53. 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.108.829523 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McGillion MH, Croxford R, Watt-Watson J et al. Cost of illness for chronic stable angina patients enrolled in a self-management education trial. Can J Cardiol 2008;24:759–64. 10.1016/S0828-282X(08)70680-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stewart S, Murphy NF, Walker A et al. The current cost of angina pectoris to the National Health Service in the UK. Heart 2003;89:848–53. 10.1136/heart.89.8.848 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) Pathway. Managing stable angina. http://pathways.nice.org.uk/pathways/stable-angina#path=view%3A/pathways/stable-angina/managing-stable-angina.xml&content=view-node%3Anodes-anti-anginal-drug-treatment (accessed 19 Aug 2015).

- 9.Chaitman BR, Pepine CJ, Parker JO et al. Combination Assessment of Ranolazine In Stable Angina (CARISA) Investigators. Effects of ranolazine with atenolol, amlodipine, or diltiazem on exercise tolerance and angina frequency in patients with severe chronic angina: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2004;291:309–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stone PH, Gratsiansky NA, Blokhin A et al. Antianginal efficacy of ranolazine when added to treatment with amlodipine: the ERICA (Efficacy of Ranolazine in Chronic Angina) trial. J Am Coll Cardiol 2006;48:566–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kosiborod M, Arnold SV, Spertus JA et al. Evaluation of ranolazine in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and chronic stable angina: results from the TERISA randomized clinical trial (Type 2 Diabetes Evaluation of Ranolazine in Subjects with Chronic Stable Angina). J Am Coll Cardiol 2013;61:2038–45. 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.02.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Husereau D, Drummond M, Petrou S et al. Consolidated Health Economic Evaluation Reporting Standards (CHEERS) statement. BMJ 2013;346:f1049 10.1136/bmj.f1049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Spertus JA, Winder JA, Dewhurst TA et al. Development and evaluation of the Seattle Angina Questionnaire: a new functional status measure for coronary artery disease. J Am Coll Cardiol 1995;25:333–41. 10.1016/0735-1097(94)00397-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang Z, Kolm P, Boden WE et al. The cost-effectiveness of percutaneous coronary intervention as a function of angina severity in patients with stable angina. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 2011;4:172–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.The National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence Decision Support Unit. Technical support document 10: The use of mapping methods to estimate health state utility values. http://www.nicedsu.org.uk/TSD%2010%20mapping %20FINAL.pdf (accessed 6 Mar 2015).

- 16.MedicinesComplete, British National Formulary. https://www.medicinescomplete.com/about/subscribe.htm (accessed 6 Mar 2015).

- 17.Consumer Price Indexes (CPI). US Bureau of Labor Statistics, Division of Consumer Prices and Price Indexes. http://www.bls.gov/cpi/ (accessed 2 Jun 2013).

- 18.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Donepezil, rivastigmine, galantamine and memantine for the treatment of Alzheimer's disease (including a review of TA19). http://guidance.nice.org.uk/?action=byID&o=11599 (accessed 2 Jun 2013).

- 19.Slof J, Gras A. Sativex® in multiple sclerosis spasticity: a cost-effectiveness model. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res 2012;12:439–41. 10.1586/erp.12.40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hidalgo-Vega A, Ramos-Goñi JM, Villoro R. Cost-utility of ranolazine for the symptomatic treatment of patients with chronic angina pectoris in Spain. Eur J Health Econ 2014;15:917–25. 10.1007/s10198-013-0534-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lucioni DC, Mazzi S.. Una valutazione economic de ranolazina add-on nel trattamento dell'angina stabile cronica. PharmacoEcono Ital Res Artic 2009;11:141–52. 10.1007/BF03320519 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gorokhova SG, Ryazhenov VV, Gorokhov et al. Cost-effectiveness of ranolazine for the treatment of angina pectoris in Russia. Value Health 2014;17:A487 10.1016/j.jval.2014.08.1429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.European Medicines Agency. Ranexa: European public assessment report product information: Annex I—Summary of product characteristics. http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/EPAR_-_Product_Information/human/000805/WC500045937.pdf (accessed 2 Apr 2015).

- 24.Koren MJ, Crager MR, Sweeney M. Long-term safety of a novel antianginal agent in patients with severe chronic stable angina: the Ranolazine Open Label Experience (ROLE). J Am Coll Cardiol 2007;49:1027–34. 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.10.067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Arnold SV, Morrow DA, Wang K et al. , MERLIN-TIMI 36 Investigators. Effects of ranolazine on disease-specific health status and quality of life among patients with acute coronary syndromes: results from the MERLIN-TIMI 36 randomized trial. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 2008;1:107–15. 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.108.798009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]