Abstract

Objectives

Agriculture has undergone major changes, and farmers have been found to have a high prevalence of depression symptoms. We investigated the risk of work disability in Norwegian farmers compared with other occupational groups, as well as the associations between symptoms of anxiety and depression and future disability pension.

Methods

We linked working participants of the HUNT2 Survey (1995–97) aged 20–61.9 years, of whom 3495 were farmers and 25 521 had other occupations, to national registry data on disability pension, with follow-up until 31 December 2010. We used Cox proportional hazards regression to estimate hazard ratios (HRs) of disability pension, and to investigate the associations between symptoms of anxiety and depression caseness at baseline (score on the anxiety or depression subscales of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) ≥8) and disability pension.

Results

Farmers had a twofold increased risk of disability pension (age-adjusted and sex-adjusted HR 2.07, 95% CI 1.80 to 2.38) compared with higher grade professionals. Farmers with symptoms of depression caseness had a 53% increased risk of disability pension (HR 1.53, 95% CI 1.25 to 1.87) compared with farmers below the cut-off point of depression caseness symptoms, whereas farmers with symptoms of anxiety caseness had a 51% increased risk (HR 1.51, 95% CI 1.23 to 1.86).

Conclusions

Farmers have an increased risk of disability pension compared with higher grade professionals, but the risk is lower than in most other manual occupational groups. Farmers who report high levels of depression or anxiety symptoms are at substantially increased risk of future work disability, and the risk increase appears to be fairly similar across most occupational groups.

Keywords: PSYCHIATRY, OCCUPATIONAL & INDUSTRIAL MEDICINE, PUBLIC HEALTH

Strengths and limitations of this study.

We used data from a large total population-based cohort, the Nord-Trøndelag Health Survey 2 (HUNT2) in Norway, with a high participation rate. Agriculture is an important industry in the region, and the number of farmers who participated in HUNT2 is relatively high.

The study used a cohort design with a long follow-up time.

The end point, disability pension, was measured using national registry data.

A considerable number of participants stated that they had several occupations. We classified these participants according to the occupation with the highest socioeconomic status, but do not know if it was their main occupation.

Despite the size of the HUNT2 Survey, the number of events in some occupational groups was still low.

Introduction

Farmers are exposed to a wide array of work-related stressors, which include a hazardous physical work environment and long working hours,1 as well as financial difficulties and other uncertainties associated with farming.2 The ongoing structural changes in agriculture may be another source of stress.3 While farm size continues to increase in developed countries, the number of farmers decreases4 and anticipation of job loss has been shown to affect health even before a change in employment status occurs.5

Results of studies on the mental health of farmers vary. A systematic review found no conclusive evidence that the mental health of farmers differs from that of the general population, although the authors did conclude that farming is associated with ‘a unique set of characteristics’ which may be harmful to mental health.2 Two large cross-sectional studies which were not included in the systematic review found that Norwegian farmers had an average prevalence of anxiety symptoms and a high prevalence of depression symptoms compared with other occupational groups.6 7

However, the interpretation of occupational studies is complicated by several factors. Occupation is one of the three main ways of characterising socioeconomic status,8 making it a marker for socioeconomic conditions and health behaviours that extend beyond the work environment only. In addition, confounding due to self-selection (‘the healthy worker effect’) may introduce bias,9 especially in cross-sectional studies.10 This self-selection includes both selection of healthy people into employment and selection of unhealthy people out of the workforce,9 and is more pronounced in physically demanding occupations.11

Disability pension is one of the major premature ways out of the workforce in Norway. In 2014, 9.4% of the population aged 18–67 received disability pension.12 Depression, anxiety and low socioeconomic status are associated with an increased risk of disability pension,13 14 but the impact of anxiety or depression on the risk of future disability pension may not be the same in different occupational groups. Farmers differ from other manual occupations in several respects. Norwegian farms are largely family-owned, and are inherited by the oldest child (formerly the oldest son). In addition, farmers are generally self-employed, and thus have a higher degree of work autonomy than most other manual occupations.1 Uncertainties regarding farm succession in the family,15 or practical and financial consequences of being self-employed, may play a role in the disability pension process in farmers. In addition, farmers appear particularly reluctant to seek medical help for mental illness due to stigma.3 We hypothesised that these or other factors which are unique to farming may result in a lower selection of farmers with depression into disability pension than in other occupations. If farmers with depression stay in the workforce longer than people with depression who work in other occupations, it may be one of the explanations for the high prevalence of depression symptoms found in cross-sectional studies of Norwegian farmers, rather than an increased incidence of depression.

In the present study, we aimed to investigate the risk of disability pension in Norwegian farmers compared with other occupational groups, using data from a large prospective population-based cohort with both health and occupational data. Further, we investigated the associations between symptoms of anxiety and depression and future disability pension, in farmers as well as in other occupational groups.

Materials and methods

The HUNT Study (Helseundersøkelsen i Nord-Trøndelag, the Nord-Trøndelag Health Study) includes three large total population-based cohorts from Nord-Trøndelag County, Norway: HUNT1 (1984–1986), HUNT2 (1995–1997) and HUNT3 (2006–2008), with 125 000 participants in total.16–18 Nord-Trøndelag County is situated in central Norway, and has around 135 000 inhabitants. The county has a large agricultural population and is largely rural; the largest of its six main towns has around 21 000 inhabitants.19

We used HUNT2 as the baseline for our study. All 92 936 residents of Nord-Trøndelag aged 20 and above were invited to take part in HUNT2, and 66 140 participated (participation rate 71.2%). Data on the participants were collected using several questionnaires, as well as measurements such as weight and height.17 In total, 65 232 answered the first questionnaire (Q1) of HUNT2, and we used this population as the base for our study. Using the unique 11-digit personal identification number given to all residents of Norway, HUNT2 was linked with national registry data from Statistics Norway on disability pensions and retirement pensions. To be eligible for a disability pension in Norway, you must be aged between 18 and 67 years, and your ability to work must be permanently reduced by at least 50% due to illness or injury. This tax financed scheme covers all residents of Norway.20

Study participants

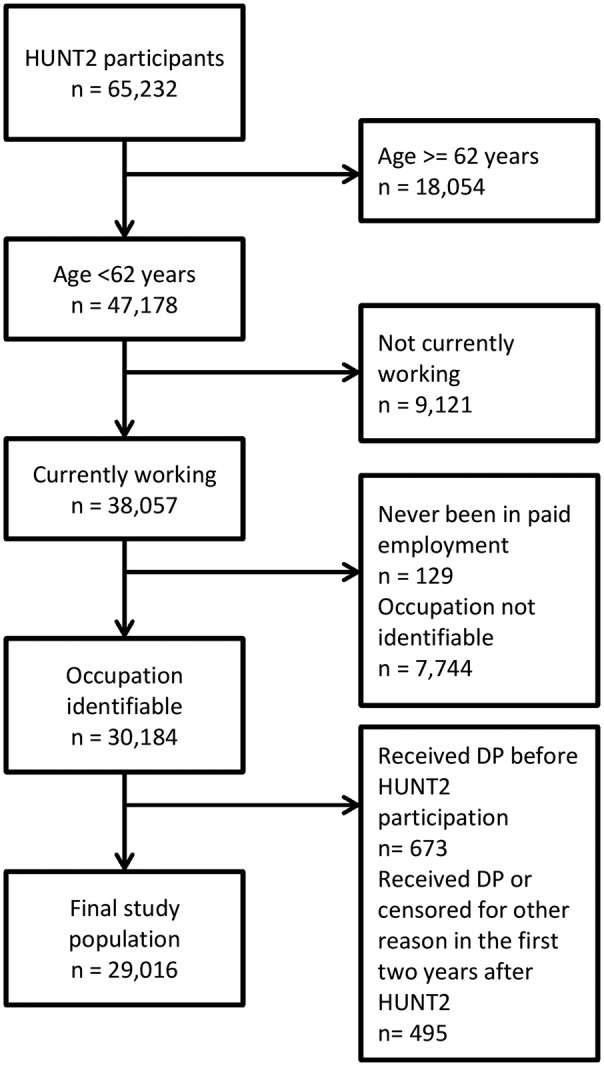

The selection criteria for our study were: (1) age <62 years at the time of participation in HUNT2, (2) currently working, (3) available occupation data and (4) not currently receiving disability pension, full or partial or having received disability pension in the past. A flow chart showing the selection of study participants is shown in figure 1.

Figure 1.

Selection of study participants. The HUNT2 Survey (1995–97). HUNT2, Nord-Trøndelag Health Survey 2; DP=disability pension.

The statutory age of retirement in Norway is 67 years. The process of receiving a disability pension is lengthy, and we excluded participants aged 62 years or older to avoid possible bias resulting from participants very near the statutory age of retirement who may not have time to reach the end point. There were 47 178 HUNT2 participants aged 61.9 years or younger at the time of screening, 38 057 of whom stated that they were currently in paid employment and/or were self-employed. However, 129 of them also stated that they had never been in paid employment and were excluded, as were 7744 who did not have an identifiable occupation. The questions on occupation were on questionnaire 2 (Q2), which was handed out at the health examination station at the time of participation and returned by mail. This resulted in a lower participation rate on Q2 than on Q1, which was sent by mail together with the study invitation and handed in at the time of study participation. Of the 7744 who did not have an identifiable occupation, 6152 (79.4%) had not returned Q2.

We excluded 673 participants who had received disability pension, full or partial, before participation in HUNT2. To minimise reverse causality, we excluded the first 2 years of follow-up, including the 495 participants who received a disability pension or were censored due to retirement pension, death or emigration in this period. Thus, our final study population consisted of 29 016 people.

Measurement of occupation

Measurement of occupation was based on self-report. The occupational groups used in HUNT2 were comparable to the Erikson-Goldthorpe-Portocarero (EGP) social class scheme,21 and we used a simplified version of the EGP scheme. The EGP scheme uses characteristics of employment relations, such as decision latitude and job autonomy, to classify occupations and there is no implicit hierarchical rank.22 A substantial proportion of the study participants (9.1%) stated that they had two or more occupations and, for the purpose of our study, we assigned one occupation to each respondent. We assumed that if a respondent had several occupations, the occupation having the highest socioeconomic status would be the one exerting the main influence on health. Consequently, we classified the respondents with two or more occupations according to their presumed highest ranking occupation.

The occupational groups in HUNT2, in the order of decreasing socioeconomic status used by us, were: (1) ‘Management position in public or private enterprise,’ (2) ‘Self-employed professional (eg, dentist, lawyer),’ (3) ‘Lower professional occupation (eg, nurse, technician, teacher),’ (4) ‘Non-professional occupation (shop, office, public service),’ (5) ‘Farmer or forest owner,’ (6) ‘Self-employed businessperson,’ (7) ‘Skilled worker, artisan, foreman,’ (8) ‘Driver, chauffeur,’ (9) ‘Fisherman,’ and (10) ‘Semiskilled, unskilled worker’. We merged some of the 10 occupational groups from HUNT2 into the following six categories based on the EGP social class scheme: Higher grade professionals (1, 2), lower grade professionals (3), routine non-manual workers (4), farmers (5), self-employed businessmen (6), skilled manual workers (7–9) and unskilled manual workers (10).

Measurement of symptoms of anxiety and depression

We used the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) as a measure of symptoms of anxiety and depression. The HADS is a screening tool consisting of 14 questions on a self-administered questionnaire. There are seven questions related to anxiety (HADS-A) and seven questions related to depression (HADS-D). Each question is scored on a scale from 0 to 3, yielding two subscales ranging from 0 to 21, where a higher score indicates a higher level of distress.23 We defined having valid HADS-A or HADS-D scores as having answered at least five out of the seven questions on the HADS-A or HADS-D subscale, respectively. If a participant had answered five or six questions on one subscale, the respondent's total subscale score was multiplied by 7/5 or 7/6, respectively. We used a cut-off of eight to define ‘caseness’ on both subscales, indicating a possible and probable case of anxiety or depression. This cut-off has been found to give an optimal balance between sensitivity and specificity, both of which are around 0.80 for both anxiety and depression.24

Statistical methods

We used Directed Acyclic Graphs (DAGs) to evaluate possible confounding.25 We considered age and sex to be confounders, in the association between occupation and disability pension, and in the association between depression or anxiety and disability pension. We did not adjust for education, because both education and occupation are ways of measuring socioeconomic status.8

We estimated the HR of disability pension in different occupational groups using the Cox proportional hazard regression analysis. We started follow-up 2 years after participation in HUNT2. The end point was the date of being granted disability pension. Subjects were censored at the date of retirement pension, loss to follow-up (emigration), age 67 or death, whichever came first. The dates of death of HUNT participants were updated regularly from the National Registry. Right censoring was at 31 December 2010, which was the last day for which data on disability pensions were available. The analyses were performed both stratified by and adjusted for sex. We adjusted for age, and included occupational group as a categorical variable in the model.

Whether physical health status at baseline is a mediator or a confounder in the relationship between occupation and disability pension is debatable, but we adjusted for it in model 2. Since answering ‘yes’ to the question “Do you suffer from any long-term illness or injury of a physical or psychological nature that impairs your functioning in everyday life? (Long-term means at least 1 year)” could also include anxiety or depression, we used its follow-up question as a measure of long-lasting physical illness: “If yes, how would you describe your impairment due to physical illness?” The categories were ‘slight’, ‘moderate’ or ‘severe’. Anyone who had not answered this follow-up question was classified as ‘no’, except respondents who had not answered the first question on having any long-lasting illness or injury, who were set to missing.

We used the Cox proportional hazard regression model to investigate the association between symptoms of anxiety or depression caseness and future disability pension in different occupational groups. The analyses were stratified by occupational group. We entered symptoms of anxiety caseness as a dichotomous variable in the model, and used study participants in the same stratum (occupational group) without symptoms of anxiety caseness as the reference category. In model 1, we adjusted for age and sex. We considered long-lasting physical illness to be a confounder in the relationship between symptoms of anxiety caseness and disability pension, and adjusted for it in model 2. We then repeated the analyses, using symptoms of depression caseness instead of anxiety.

To estimate the impact symptoms of anxiety and depression caseness had on the 5-year risk difference for being granted a disability pension, we estimated the marginal effect using logistic regression, adjusting for sex and age. Since younger workers have a low risk of being granted disability pension, we also estimated the 5-year risk difference in study participants aged ≥50 only.

In the sensitivity analyses, we analysed the time periods <7 years and ≥7 years of follow-up separately. The proportional hazards assumption on the models was also tested using log-minus-log plots.

The analyses were conducted using STATA V.13.1.

Results

Characteristics of the study participants are shown in table 1. Of all the occupational groups, farmers had the highest mean depression symptoms score and the highest prevalence of depression caseness. Farmers also reported the highest prevalence of poor or not very good self-reported health, and of long-lasting physical impairment.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the study participants

| Higher grade professionals |

Lower grade professionals |

Routine non-manual workers |

Farmers |

mean | SD | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Per cent | mean | SD | n | Per cent | mean | SD | n | Per cent | mean | SD | n | Per cent | |||

| n | 3130 | 5948 | 6083 | 3495 | ||||||||||||

| Women | 3130 | 25.7 | 5948 | 66.9 | 6083 | 80.5 | 3495 | 26.3 | ||||||||

| Age | 3130 | 44.5 | 8.8 | 5948 | 41.9 | 9.6 | 6083 | 41.5 | 10.6 | 3495 | 43.7 | 10.2 | ||||

| Education | 3120 | 5934 | 6045 | 3459 | ||||||||||||

| Less than secondary school | 26.7 | 19.1 | 68.6 | 83.8 | ||||||||||||

| Secondary school graduate | 7.4 | 5.4 | 19.6 | 9.9 | ||||||||||||

| Higher education | 65.9 | 75.5 | 11.8 | 6.3 | ||||||||||||

| Self-rated health ‘poor’ or ‘not very good’ | 3111 | 10.1 | 5902 | 12.1 | 6032 | 14.1 | 3474 | 17.3 | ||||||||

| Long-lasting physical impairment* | 3083 | 6.1 | 5818 | 6.8 | 5925 | 6.6 | 3375 | 8.4 | ||||||||

| Long-lasting mental health impairment* | 3083 | 2.6 | 5818 | 3.2 | 5925 | 3.4 | 3375 | 3.2 | ||||||||

| Daily smoker | 2996 | 22.9 | 5656 | 21.4 | 5845 | 33.4 | 3301 | 23.2 | ||||||||

| Hours of paid work per week | 2990 | 39.4 | 8.8 | 5528 | 33.4 | 8.8 | 5823 | 30.8 | 10.4 | 1850 | 36.8 | 19.2 | ||||

| HADS-A score | 3115 | 4.0 | 3.1 | 5916 | 4.0 | 3.0 | 6045 | 4.2 | 3.2 | 3454 | 4.1 | 3.1 | ||||

| Caseness HADS-A† | 3115 | 13.6 | 5916 | 12.6 | 6045 | 14.3 | 3454 | 13.8 | ||||||||

| HADS-D score | 3116 | 2.9 | 2.8 | 5924 | 2.7 | 2.6 | 6057 | 2.9 | 2.7 | 3462 | 3.7 | 3.0 | ||||

| Caseness HADS-D‡ | 3116 | 7.3 | 5924 | 5.6 | 6057 | 6.5 | 3462 | 11.6 | ||||||||

| Self-employed |

Skilled manual workers |

Unskilled manual workers |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Per cent | mean | SD | n | Per cent | mean | SD | n | Per cent | mean | SD | |

| n | 1388 | 4647 | 4325 | |||||||||

| Women | 1388 | 38.7 | 4647 | 15.2 | 4325 | 56.3 | ||||||

| Age | 1388 | 43.0 | 9.8 | 4647 | 40.2 | 10.3 | 4325 | 40.4 | 11.1 | |||

| Education | 1380 | 4622 | 4279 | |||||||||

| Less than secondary school | 76.3 | 88.0 | 85.6 | |||||||||

| Secondary school graduate | 10.5 | 8.2 | 11.5 | |||||||||

| Higher education | 13.2 | 3.9 | 2.9 | |||||||||

| Self-rated health ‘poor’ or ‘not very good’ | 1385 | 14.3 | 4624 | 14.2 | 4300 | 16.6 | ||||||

| Long-lasting physical impairment* | 1351 | 7.4 | 4522 | 7.2 | 4178 | 7.7 | ||||||

| Long-lasting mental health impairment* | 1351 | 2.4 | 4522 | 3.6 | 4178 | 4.6 | ||||||

| Daily smoker | 1337 | 33.0 | 4459 | 34.0 | 4153 | 41.0 | ||||||

| Hours of paid work per week | 989 | 39.0 | 14.6 | 4443 | 37.5 | 7.4 | 4025 | 31.7 | 10.9 | |||

| HADS-A score | 1374 | 4.4 | 3.3 | 4613 | 3.9 | 3.0 | 4282 | 4.3 | 3.3 | |||

| Caseness HADS-A† | 1374 | 15.9 | 4613 | 11.9 | 4282 | 15.1 | ||||||

| HADS-D score | 1378 | 3.2 | 2.7 | 4617 | 3.1 | 2.7 | 4291 | 3.1 | 2.8 | |||

| Caseness HADS-D‡ | 1378 | 7.8 | 4617 | 7.0 | 4291 | 8.0 | ||||||

Working participants of the HUNT2 Survey (1995–97), aged 20–61.9 years of age.

*Lasting at least 1 year, causing impairment of daily function.

†Caseness=score ≥8 on the anxiety symptom subscale.

‡Caseness=score ≥8 on the depression symptom subscale.

HADS-A, the anxiety subscale of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; HADS-D, the depression subscale of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; SD, standard deviation.

The results in table 2 showed a decreased risk of disability pension in occupational groups of higher socioeconomic status. Farmers had a twofold increased risk (age-adjusted and sex-adjusted HR 2.07, 95% CI 1.80 to 2.38) compared with higher grade professionals. This risk increase in farmers was lower than in other manual occupations, but higher than in non-manual occupations. Compared with male higher grade professionals, male farmers had a 145% higher risk (HR 2.45, 95% CI 2.07 to 2.90) of disability pensioning. In women, the risk increase was 47% (HR 1.47, 95% CI 1.15 to 1.89).

Table 2.

HRs with 95% CIs for disability pension according to occupational position

| Model 1 |

Model 2 |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | n events | Rate* | 95% CI | HR | 95% CI | HR | 95% CI | |

| Both sexes | ||||||||

| Higher grade professionals | 3130 | 287 | 8.3 | 7.4 to 9.3 | 1 | NA | 1 | NA |

| Lower grade professionals | 5948 | 731 | 10.9 | 10.2 to 11.8 | 1.38 | 1.20 to 1.58 | 1.38 | 1.19 to 1.59 |

| Non-manual routine workers | 6083 | 946 | 14.3 | 13.4 to 15.2 | 1.71 | 1.49 to 1.96 | 1.72 | 1.49 to 1.98 |

| Farmers | 3495 | 608 | 16.3 | 15.1 to 17.7 | 2.07 | 1.80 to 2.38 | 2.00 | 1.73 to 2.31 |

| Self-employed | 1388 | 269 | 18.1 | 16.1 to 20.4 | 2.40 | 2.03 to 2.84 | 2.40 | 2.02 to 2.84 |

| Skilled manual workers | 4647 | 620 | 12.0 | 11.1 to 13.0 | 2.20 | 1.92 to 2.54 | 2.13 | 1.85 to 2.47 |

| Unskilled manual workers | 4325 | 821 | 17.7 | 16.5 to 19.0 | 2.58 | 2.25 to 2.96 | 2.54 | 2.21 to 2.93 |

| Total person-time at risk: | 318 009 | |||||||

| Women | ||||||||

| Higher grade professionals | 803 | 95 | 10.6 | 8.6 to 12.9 | 1 | NA | 1 | NA |

| Lower grade professionals | 3981 | 544 | 12.1 | 11.2 to 13.2 | 1.23 | 0.99 to 1.53 | 1.27 | 1.01 to 1.59 |

| Non-manual routine workers | 4899 | 814 | 15.3 | 14.3 to 16.4 | 1.46 | 1.18 to 1.80 | 1.52 | 1.22 to 1.90 |

| Farmers | 919 | 181 | 18.8 | 16.2 to 21.7 | 1.47 | 1.15 to 1.89 | 1.46 | 1.13 to 1.90 |

| Self-employed | 537 | 105 | 18.2 | 15.0 to 22.0 | 1.83 | 1.39 to 2.41 | 1.82 | 1.36 to 2.43 |

| Skilled manual workers | 707 | 117 | 14.8 | 12.4 to 17.8 | 1.93 | 1.47 to 2.53 | 1.92 | 1.44 to 2.54 |

| Unskilled manual workers | 2434 | 545 | 21.2 | 19.5 to 23.1 | 2.14 | 1.72 to 2.66 | 2.18 | 1.74 to 2.73 |

| Total person-time at risk: | 156 051 | |||||||

| Men | ||||||||

| Higher grade professionals | 2327 | 192 | 7.5 | 6.5 to 8.6 | 1 | NA | 1 | NA |

| Lower grade professionals | 1967 | 187 | 8.5 | 7.4 to 9.8 | 1.27 | 1.04 to 1.55 | 1.27 | 1.03 to 1.56 |

| Non-manual routine workers | 1184 | 132 | 10.1 | 8.5 to 12.0 | 1.78 | 1.43 to 2.22 | 1.72 | 1.37 to 2.16 |

| Farmers | 2576 | 427 | 15.5 | 14.1 to 17.0 | 2.45 | 2.07 to 2.90 | 2.35 | 1.98 to 2.80 |

| Self-employed | 851 | 164 | 18.1 | 15.5 to 21.1 | 2.80 | 2.27 to 3.45 | 2.82 | 2.28 to 3.49 |

| Skilled manual workers | 3940 | 503 | 11.5 | 10.5 to 12.5 | 2.40 | 2.03 to 2.83 | 2.31 | 1.94 to 2.74 |

| Unskilled manual workers | 1891 | 276 | 13.3 | 11.8 to 15.0 | 2.96 | 2.46 to 3.56 | 2.87 | 2.37 to 3.47 |

| Total person-time at risk: | 161 959 | |||||||

The HUNT2 Survey (1995–97).

Cox proportional hazards regression. Follow-up from 2 years after baseline measurements until 31 December 2010. Model 1: Adjusted for age. Model 2: Adjusted for age and long-lasting limiting physical illness at baseline.

*Rate of disability pension per 1000 person-years.

NA, not applicable.

The association between symptoms of anxiety caseness and the risk of disability pension in different occupational groups, adjusted for age and sex, are shown in table 3. Farmers with symptoms of anxiety caseness had a 51% increased risk of disability pension of (HR 1.51, 95% CI 1.23 to 1.86) compared with farmers without symptoms of anxiety caseness. Symptoms of anxiety caseness increased the risk of disability pension in all the occupational groups, and the HRs were quite similar, with a range from 1.51 to 1.75. The 5-year risk difference in disability pension is shown in online supplementary table S1. The 5-year risk differences were higher in the group aged ≥50 than for all ages, but the risk differences were relatively similar in the different occupational groups.

Table 3.

HRs with 95% CIs for disability pension according to baseline symptoms of anxiety

| Model 1 |

Model 2 |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | n events | n events with HADS-A ≥8 | Person-time at risk | HR | 95% CI | HR | 95% CI | |

| Higher grade professionals | 3115 | 285 | 53 | 34 595 | 1.62 | 1.12 to 2.18 | 1.38 | 1.01 to 1.88 |

| Lower grade professionals | 5916 | 718 | 139 | 66 460 | 1.70 | 1.41 to 2.04 | 1.64 | 1.36 to 1.98 |

| Non-manual routine workers | 6045 | 934 | 191 | 65 948 | 1.66 | 1.42 to 1.95 | 1.59 | 1.35 to 1.88 |

| Farmers | 3454 | 599 | 109 | 36 892 | 1.51 | 1.23 to 1.86 | 1.36 | 1.09 to 1.69 |

| Self-employed | 1374 | 262 | 55 | 14 700 | 1.75 | 1.30 to 2.37 | 1.88 | 1.38 to 2.57 |

| Skilled manual workers | 4613 | 613 | 113 | 51 396 | 1.63 | 1.33 to 2.00 | 1.49 | 1.19 to 1.85 |

| Unskilled manual workers | 4282 | 804 | 177 | 46 019 | 1.65 | 1.40 to 1.95 | 1.46 | 1.22 to 1.74 |

The HUNT2 Survey (1995–97).

Cox proportional hazard regression.

Follow-up from 2 years after baseline measurements until 31 December 2010.

Model 1: Adjusted for age and sex.

Model 2: Adjusted for age, sex and long-lasting limiting physical illness at baseline.

HADS-A, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, anxiety subscale. Cut-off for caseness: ≥8.

The association between symptoms of depression caseness and the risk of disability pension in different occupational groups are presented in table 4. Farmers with symptoms of depression caseness had a 53% increased risk of disability pension of (HR 1.53, 95% CI 1.25 to 1.87) compared with farmers without symptoms of depression caseness. Symptoms of depression caseness increased the risk of work disability in all occupational groups, but the variation in HR was higher than that for anxiety. On the basis of the relative risk measures (HR), we found that higher grade professionals and unskilled manual workers had the highest HRs following the high depression symptoms load at baseline. However, when estimating an absolute measure, the 5-year risk difference showed only minor differences between occupations (see online supplementary table S1). The risk difference in the self-employed group was negative (−1.6%, 95% CI −15.8% to 12.7%), suggesting that the self-employed with symptoms of depression caseness at baseline had a lower risk of disability pension than their colleagues without symptoms of depression caseness at baseline. However, the estimate is uncertain because of the small number of events with symptoms of depression caseness in the self-employed category.

Table 4.

HRs with 95% CIs for disability pension according to baseline symptoms of depression

| Model 1 |

Model 2 |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | n events | n Events with HADS-D ≥8 | Person-time at risk | HR | 95% CI | HR | 95% CI | |

| Higher grade professionals | 3116 | 285 | 48 | 34 602 | 2.43 | 1.78 to 3.31 | 1.93 | 1.38 to 2.68 |

| Lower grade professionals | 5924 | 723 | 67 | 66 516 | 1.59 | 1.23 to 2.04 | 1.50 | 1.16 to 1.94 |

| Non-manual routine workers | 6057 | 937 | 99 | 66 061 | 1.66 | 1.35 to 2.05 | 1.48 | 1.19 to 1.85 |

| Farmers | 3462 | 602 | 116 | 36 933 | 1.53 | 1.25 to 1.87 | 1.36 | 1.10 to 1.69 |

| Self-employed | 1378 | 265 | 29 | 14 725 | 1.30 | 0.88 to 1.92 | 1.18 | 0.79 to 1.76 |

| Skilled manual workers | 4617 | 613 | 71 | 51 440 | 1.35 | 1.05 to 1.73 | 1.20 | 0.92 to 1.56 |

| Unskilled manual workers | 4291 | 807 | 123 | 46 089 | 1.93 | 1.59 to 2.34 | 1.71 | 1.40 to 2.09 |

The HUNT2 Survey (1995–97).

Cox proportional hazard regression.

Follow-up from 2 years after baseline measurements until 31 December 2010.

Model 1: Adjusted for age and sex.

Model 2: Adjusted for age, sex and long-lasting limiting physical illness.

HADS-D, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, depression subscale. Cut-off for caseness: ≥8.

Results of the sensitivity analyses can be found in online supplementary tables S2–4. The HRs of disability pension were similar in the first 7 and past 7 years of follow-up in most of the occupational groups. There was a tendency for the risk increase following symptoms of depression or anxiety caseness at baseline to be stronger in the first 7 years of follow-up than in the last 7 years of follow-up.

Discussion

We found that although farmers, especially males, had an increased risk of disability pension compared with higher grade professionals, they had a lower risk of disability pension than most other manual occupational groups. Symptoms of anxiety and symptoms of depression were risk factors for future disability pension in farmers as well as in other occupational groups, and there did not appear to be any substantial differences between occupations.

Even though farmers have a physically demanding job, and had the highest prevalence of ‘poor’ or ‘not very good’ self-reported health at baseline, we found that farmers had a low risk of disability pension compared with most other manual occupational groups. Although the high prevalence of poor self-reported health may partially be caused by farmers having a higher mean age than most of the other occupational groups, this suggests that farmers may work longer with compromised health before receiving a disability pension. A Swedish study found that farmers continued to work full-time or part-time around retirement age to a larger extent than employees.26 Farmers may stay occupationally active despite health symptoms due to uncertainty surrounding farm succession,15 being self-employed or other unique social or practical factors related to farming.2 Another possible explanation may be that farmers have a high level of control or autonomy in their work situation.1 In the Job Demand Control (JDC) model, the combination of high job demands and low job control is associated with mental strain.27 Farmers have been found to have ‘low strain’ jobs, characterised by low levels of work intensity and high levels of job autonomy, and thus are at low risk of stress and with more favourable health outcomes.28 This is not in accordance with our findings of high prevalences of depression caseness and self-reported poor health in farmers.

In addition to the potential beneficial effect of high job control on health, a high level of job control may also enable farmers to adjust their work so they can keep working despite having a health problem. They may decrease or change their production, or work slower, but compensate by working longer hours. The mean number of hours of paid work per week among farmers is surprisingly low in this study, and is not in accordance with the literature,1 including a study from HUNT3 (2006–2008), in which 81.9% of male farmers reported working more than 40 h per week.7 It is unknown whether our finding actually reflects the true number of work hours for farmers, or whether there may be under-reporting due to the phrasing of the question, which asked for the number of hours of ‘paid work’ per week. It is possible that the distinction between paid and unpaid working hours may get blurred on a farm, especially if the respondent also has an off-farm job.

The literature on mental health and disability pension in farmers is scarce, but in a cohort of Finnish farmers, high psychological distress was associated with an increased cause-specific risk of disability pension during the 10-year follow-up period, including disability pensions granted for all causes and for depression.29 Symptoms of anxiety and depression were associated with an increased risk of disability pension in all occupations in our study. However, two occupational groups, in the opposite ends of the socioeconomic spectrum, had a stronger association between symptoms of depression and future disability pension than the other occupational groups: Higher grade professionals and unskilled manual workers. Higher grade professionals generally have the lowest risk of adverse health outcomes,8 but it may be particularly demanding to stay occupationally active when suffering from depression if your job involves high demands on social and cognitive performance. However, the risk difference in higher grade professionals is similar to that of almost all of the other occupational groups. This suggests that higher grade professionals had a higher HR than the other occupational groups in the stratified analyses because of their underlying low risk of disability pension. On the other hand, although unskilled manual workers had the highest HR of receiving disability pension, they still had a relatively strong association between symptoms of depression caseness and disability pension, as well as the highest risk difference of all the occupational groups. This suggests that unskilled manual workers, who have the least amount of job control, and are exposed to the most adverse socioeconomic conditions, may be more likely to receive a disability pension following symptoms of depression at baseline than other occupational groups. This supports the findings of a large Finnish study, in which return to work after a work disability episode due to depression was slower in workers of low socioeconomic status and recurrent work disability episodes due to depression were more common.30

Having a physically demanding job has been shown to be associated with an increased risk of disability pension, even compared with workers in other blue-collar jobs in the same industry.31 This suggests that staying in the workforce while having chronic, physical pain may be more difficult when having a physically demanding job. However, our results indicate that despite socioeconomic differences in health8 and healthcare utilisation,32 this may not be the case for mental illness, such as anxiety and depression. The risk increase associated with anxiety and depression caseness at baseline appeared to be relatively similar across most occupational groups, with the possible exception of unskilled manual workers. This is consistent with a review article which found that socioeconomic status was not related to the recurrence of a major depressive disorder.33 Thus, it does not seem likely that a decreased selection of farmers with depression into disability pension is part of the explanation for the high prevalence of depression symptoms found in farmers. This suggests that other causes, such as stress, financial problems, a high workload or other factors, may be behind the cross-sectional findings of a high prevalence of depression symptoms in Norwegian farmers.6 7

Strengths and limitations

Our study has several strengths. HUNT2 is a total population-based survey with a high participation rate. For end points and censoring, we used national registry data on disability pension, retirement pension and death, all of which can be considered complete. Emigration was negligible and, as a result, we were able to follow a large number of men and women over a period of up to 14 years with minimal loss to follow-up. The population of Nord-Trøndelag County follows Norwegian trends in disability14 and mortality34 closely, and our results should be generalisable to other parts of Norway. The extent to which our results are generalisable to other welfare states is unknown, but we believe our results may be of interest internationally.

The HADS is not a clinical diagnosis of depression or anxiety, and a respondent can get a transiently increased score when going through, for instance, physical illness, divorce or personal loss. Compared with other occupational groups, a higher proportion of farmers reported having poor health, whereas a higher proportion of farmers were married, and a lower proportion were divorced (data not shown). We do not have data on other potentially stressful situations that may transiently influence the HADS score, but we do not have any reason to believe that farmers differ systematically from other occupational groups. Symptoms of anxiety and depression caseness were only measured once. We do not know if the participants suffered from anxiety or depressive symptoms in the years between HUNT2 participation and the end of follow-up, and the associations between anxiety or depression and disability pension were weaker in the last 7 years of follow-up than in the first 7 years. One study found that of the HUNT2 participants aged 45–64 years who reported an HADS-D score of ≥8, around 40% had a HADS-D score of ≥8 in HUNT3, 11 years later.35

The EGP scheme uses characteristics of employment relations to classify occupations, and any observed health differences between occupational groups can thus be attributable to differences in working relations, autonomy and rewards systems. This may make the EGP scheme less suitable for investigating health gradients, although the EGP scheme also inherently reflects material resources.22 Perhaps more importantly, the EGP scheme is not hierarchical and our hierarchical method of assigning group membership to participants who had several occupations therefore constitutes a weakness. For some of the occupations, it is not necessarily clear where they belong in a hierarchical system, especially in one that is based on characteristics of employment relations. This is particularly challenging for farmers, self-employed and possibly also fishermen, due to the nature of their jobs and their high degree of work autonomy. Farming is a manual occupation, but farmers have a high decision latitude; they often own large properties and run their own businesses. Fishermen may be in a similar situation as farmers, whereas the self-employed are likely to be a diverse group. Self-employed academics, such as physicians and lawyers, were included in the higher grade professionals group, but the self-employed businessmen in our study are still likely to be working in diverse fields and with varying levels of skill.

Furthermore, for the participants who had stated that they had several occupations, we do not know which occupation is their main occupation. Our assumption that the socioeconomic status of a participant was determined by the occupation with the highest socioeconomic status may not hold if that occupation was not their main occupation. This is particularly relevant because our group of interest, farmers, often have an off-farm job as well. Of the 3495 respondents we classified as farmers, 24.5% had two or more occupations. In total, 4273 respondents stated that they were farmers, and 38.2% had two or more occupations.

Even though the number of study participants is high, there were not enough cases of disability pension among participants with symptoms of anxiety or depression to stratify the analyses by sex. Thus, we were unable to investigate possible sex differences in the associations between symptoms of anxiety or depression and disability pension.

A non-participation study of HUNT3 found that non-participants had lower socioeconomic status and higher mortality than participants, and that depression was a more restricting factor for participation than anxiety.36 HUNT2 had a higher participation rate than HUNT3,18 but, assuming that the underlying processes were similar in HUNT2, both the risk of disability pension and the association between symptoms of depression caseness and disability pension are likely to be underestimated. The underestimation may be more pronounced in occupational groups of low socioeconomic status than in groups of high socioeconomic status.

Conclusions

We found that farmers had an intermediate risk of disability pension, although the risk was low compared with manual occupations. Male farmers were at higher relative risk than female farmers. Even though farming is physically demanding, our results indicate that farmers may work longer with physical health problems before receiving a disability pension than other occupations. However, despite differences in work conditions and socioeconomic status, self-reported symptoms of anxiety and depression caseness appear to have a fairly similar relation with the risk of future disability pension in most occupational groups. More research is needed to elucidate the causes of the high depression symptom level of farmers, as well as the processes surrounding disability pension in farmers.

Acknowledgments

The Nord-Trøndelag Health Study (HUNT) is a collaboration between the HUNT Research Centre (Faculty of Medicine, Norwegian University of Science and Technology NTNU), Nord-Trøndelag County Council, Central Norway Health Authority and the Norwegian Institute of Public Health. The authors would like to thank librarian Ingrid Ingeborg Riphagen for assistance with the literature search.

Footnotes

Contributors: MOT, BH, JHB and SK designed the study. MOT conducted the analyses with assistance from JHB and SK. MOT wrote the first draft of the manuscript. BH, JHB, DG and SK revised the draft, and all authors contributed to and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding: The project was funded by the Research Levy on Agricultural Products/the Agricultural Agreement Research Fund, Norway. The funders had no involvement in study design, data collection and analysis, preparation of the manuscript or the decision to publish.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: All participants of HUNT2 provided written informed consent. The HUNT Study was approved by the Regional Committee for Medical and Health Research Ethics (REC Central), as was this study (2012/1359).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Parent-Thirion A, Fernández Macías E, Hurley J, et al.Fourth European Working Conditions Survey. Luxembourg: Office for Official Publications of the European Communities, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fraser CE, Smith KB, Judd F et al. Farming and mental health problems and mental illness. Int J Soc Psychiatry 2005;51:340–9. 10.1177/0020764005060844 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kallioniemi MK, Simola A, Kinnunen B et al. Stress in farm entrepreneurs. In: Langan-Fox J, Cooper CL, eds. Handbook of stress in the occupations. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing Limited, 2011:385–406. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Donham KJ, Thelin A. Introduction and overview. In: Donham KJ, Thelin A, eds. Agricultural medicine: occupational and environmental health for the health professions. Ames: Blackwell Publishing, 2006:3–27. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ferrie JE, Shipley MJ, Marmot MG et al. Health effects of anticipation of job change and non-employment: longitudinal data from the Whitehall II study. BMJ 1995;311:1264–9. 10.1136/bmj.311.7015.1264 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sanne B, Mykletun A, Dahl AA et al. Occupational differences in levels of anxiety and depression: the Hordaland Health Study. J Occup Environ Med 2003;45:628–38. 10.1097/01.jom.0000069239.06498.2f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Torske M, Hilt B, Glasscock D et al. Anxiety and depression symptoms among farmers. The HUNT Study. J Agromedicine 2015;In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Glymour MM, Avendano M, Kawachi I. Socioeconomic status and health. In: Berkman LF, Kawachi I, Glymour MM, eds. Social epidemiology. 2nd edn New York: Oxford University Press, 2014:17–62. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rothman KJ, Greenland S, Lash TL. Validity in epidemiologic studies. In: Rothman KJ, Greenland S, Lash TL, eds. Modern epidemiology. 3rd edn Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2008:128–47. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pearce N, Checkoway H, Kriebel D. Bias in occupational epidemiology studies. Occup Environ Med 2007;64:562–8. 10.1136/oem.2006.026690 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li CY, Sung FC. A review of the healthy worker effect in occupational epidemiology. Occup Med (Lond) 1999;49:225–9. 10.1093/occmed/49.4.225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mottakere av uførepensjon som andel av befolkningen. Oslo: NAV, 2014. https://www.nav.no/no/NAV+og+samfunn/Statistikk/AAP+nedsatt+arbeidsevne+og+uforetrygd+-+statistikk/Tabeller/Mottakere+av+uf%C3%B8repensjon+som+andel+av+befolkningen+*),+etter+fylke.+Aldersstandardiserte+tall.+Pr..409157.cms (accessed 14 Sep 2015). [Google Scholar]

- 13.Knudsen AK, Overland S, Aakvaag HF et al. Common mental disorders and disability pension award: seven year follow-up of the HUSK study. J Psychosom Res 2010;69:59–67. 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2010.03.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Krokstad S, Johnsen R, Westin S. Social determinants of disability pension: a 10-year follow-up of 62 000 people in a Norwegian county population. Int J Epidemiol 2002;31:1183–91. 10.1093/ije/31.6.1183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rogers M, Barr N, O'Callaghan Z et al. Healthy ageing: farming into the twilight. Rural Society 2014;22:251–62. 10.5172/rsj.2013.22.3.251 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Holmen J, Midthjell K, Forsen L et al. [A health survey in Nord-Trondelag 1984–86. Participation and comparison of attendants and non-attendants]. Tidsskr Nor Laegeforen 1990;110:1973–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Holmen J, Midthjell K, Krüger Ø et al. The Nord-Trøndelag Health Study 1995–97 (HUNT2): objectives, contents, methods and participation. Nor Epidemiol 2003;13:19–32. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Krokstad S, Langhammer A, Hveem K et al. Cohort profile: the HUNT Study, Norway. Int J Epidemiol 2013;42:968–77. 10.1093/ije/dys095 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Population. Oslo: Statistics Norway 2015. https://www.ssb.no/statistikkbanken/selecttable/hovedtabellHjem.asp?KortNavnWeb=folkemengde&CMSSubjectArea=befolkning&PLanguage=1&checked=true (accessed 24 Mar 2015). [Google Scholar]

- 20.Disability benefit. NAV, 2011. https://www.nav.no/en/Home/Benefits+and+services/Pensions+and+pension+application+from+outside+Norway/Disability+benefit (accessed 7 Apr 2015).

- 21.Erikson R, Goldthorpe JH. The constant flux. A study of class mobility in industrial societies. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Galobardes B, Shaw M, Lawlor DA et al. Indicators of socioeconomic position. In: Oakes JM, Kaufman JS, eds. Methods in social epidemiology. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 2006:47–85. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1983;67:361–70. 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb09716.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bjelland I, Dahl AA, Haug TT et al. The validity of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. An updated literature review. J Psychosom Res 2002;52:69–77. 10.1016/S0022-3999(01)00296-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Glymour MM, Greenland S. Causal diagrams. In: Rothman KJ, Greenland S, Lash TL, eds. Modern epidemiology. 3rd edn Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2008: 183–209. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thelin A, Holmberg S. Farmers and retirement: a longitudinal cohort study. J Agromedicine 2010;15:38–46. 10.1080/10599240903389623 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Karasek RA. Job demands, job decision latitude, and mental strain: implications for job redesign. Adm Sci Q 1979;24:285–308. 10.2307/2392498 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Parent-Thirion A, Vermeylen G, van Houten G, et al.Eurofound. Fifth European working conditions survey. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Manninen P, Heliövaara M, Riihimäki H et al. Does psychological distress predict disability? Int J Epidemiol 1997;26:1063–70. 10.1093/ije/26.5.1063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ervasti J, Vahtera J, Pentti J et al. Depression-related work disability: socioeconomic inequalities in onset, duration and recurrence. PLoS ONE 2013;8:e79855 10.1371/journal.pone.0079855 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jarvholm B, Stattin M, Robroek SJ et al. Heavy work and disability pension—a long term follow-up of Swedish construction workers. Scand J Work Environ Health 2014;40:335–42. 10.5271/sjweh.3413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vikum E, Krokstad S, Westin S. Socioeconomic inequalities in health care utilisation in Norway: the population-based HUNT3 survey. Int J Equity Health 2012;11:48 10.1186/1475-9276-11-48 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hardeveld F, Spijker J, De Graaf R et al. Prevalence and predictors of recurrence of major depressive disorder in the adult population. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2010;122:184–91. 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2009.01519.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Causes of death. Oslo-Kongsvinger: Statistics Norway, 2013. (accessed 23 Jun 2014). https://www.ssb.no/statistikkbanken/selecttable/hovedtabellHjem.asp?KortNavnWeb=dodsarsak&CMSSubjectArea=helse&PLanguage=1&checked=true

- 35.Solhaug HI, Romuld EB, Romild U et al. Increased prevalence of depression in cohorts of the elderly: an 11-year follow-up in the general population-the HUNT study. Int Psychogeriatr 2012;24:151–8. 10.1017/S1041610211001141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Langhammer A, Krokstad S, Romundstad P et al. The HUNT study: participation is associated with survival and depends on socioeconomic status, diseases and symptoms. BMC Med Res Methodol 2012;12:143 10.1186/1471-2288-12-143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]