Abstract

Objective

There have been calls to remove ‘carcinoma’ from terminology for in situ cancers such as ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS), to reduce overdiagnosis and overtreatment. We investigated the effect of describing DCIS as ‘abnormal cells’ versus ‘pre-invasive breast cancer cells’ on women's concern and treatment preferences.

Setting and participants

Community sample of Australian women (n=269) who spoke English as their main language at home.

Design

Randomised comparison within a community survey. Women considered a hypothetical scenario involving a diagnosis of DCIS described as either ‘abnormal cells’ (arm A) or ‘pre-invasive breast cancer cells’ (arm B). Within each arm, the initial description was followed by the alternative term and outcomes reassessed.

Results

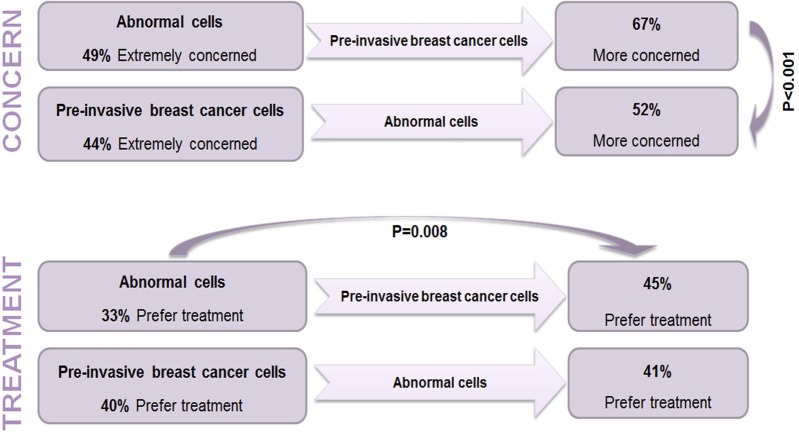

Women in both arms indicated high concern, but still indicated strong initial preferences for watchful waiting (64%). There were no differences in initial concern or preferences by trial arm. However, more women in arm A (‘abnormal cells’ first term) indicated they would feel more concerned if given the alternative term (‘pre-invasive breast cancer cells’) compared to women in arm B who received the terms in the opposite order (67% arm A vs 52% arm B would feel more concerned, p=0.001). More women in arm A also changed their preference towards treatment when the terminology was switched from ‘abnormal cells’ to ‘pre-invasive breast cancer cells’ compared to arm B. In arm A, 18% of women changed their preference to treatment while only 6% changed to watchful waiting (p=0.008). In contrast, there were no significant changes in treatment preference in arm B when the terminology was switched (9% vs 8% changed their stated preference).

Conclusions

In a hypothetical scenario, interest in watchful waiting for DCIS was high, and changing terminology impacted women's concern and treatment preferences. Removal of the cancer term from DCIS may assist in efforts towards reducing overtreatment.

Keywords: PUBLIC HEALTH

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the first study to assess the effects of alternative terms for ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) on both psychological outcomes and treatment preferences.

Participants were a national community sample including women from a range of demographic backgrounds.

The experimental design allowed inclusion of participants who were unbiased by previous knowledge and information about DCIS.

Limitations of the study include its hypothetical design, therefore women facing a real diagnosis of DCIS may respond differently.

Preferences for watchful waiting were predicated on the statement, ‘if research shows watchful waiting is a safe and effective option’; the subject of two current randomised trials of women with DCIS.

Introduction

Ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) is a pre-invasive malignancy of the breast. Since the onset of organised breast screening, its incidence has rapidly increased, with DCIS representing approximately 20% of screen-detected cancers.1 In the USA, approximately 50 000 women are diagnosed with DCIS each year2 and in Australia, around 1600 women are diagnosed annually.3 Although DCIS is divided into three grades with different rates of progression (suggested estimates range between 14% and 53% and are uncertain);4 it is almost always treated as if it were invasive cancer, with most women receiving either a mastectomy (20 000/year in the USA)5 6 or a lumpectomy, often combined with radiation therapy. A recent review by the Independent UK Panel on Breast Cancer Screening7 concluded that there is sizeable overdiagnosis and overtreatment of screen-detected breast lesions including DCIS. Although the review did not separate DCIS and invasive breast cancer in the overdiagnosis estimates (19% as a proportion of cancers diagnosed during the screening period, or 11% of breast cancer incidence during screening and for the remainder of the woman's lifetime), it is widely appreciated that the proportion of overdiagnosis is likely greater among DCIS cases. Accordingly, watchful waiting has been proposed as a potentially appropriate alternative treatment strategy for DCIS.8

It is well recognised that DCIS is challenging to define and explain, with clinicians and health-care professionals divided in opinion and practice about how to communicate it to patients.9–11 The common terms used to describe DCIS include pre-cancer, carcinoma, intraductal breast cancer, stage 0 cancer and non-invasive cancer; this terminology has been suggested as a potential driver of both confusion about the meaning of diagnosis, and distinction between DCIS and invasive cancer,12 13 and a desire for more invasive treatments.8 Experts have recently suggested that the terms cancer or carcinoma should be removed from the label and instead be reserved for conditions that are likely to progress if left untreated.14–16 Alternative terminologies removing the cancer label have been suggested,8 14 15 and include ductal intraepithelial neoplasia and indolent lesions of intraepithelial origin (IDLE).

This study set out to examine whether the use of terminology including the term cancer to describe DCIS, increased hypothetical concern and treatment preferences among a community sample of Australian women.

Method

Design

We used a randomised design within a broader community survey with female participants randomised into one of two information arms (figure 1). All participants received information about a hypothetical scenario describing DCIS without using the term DCIS itself (box 1), and participants were asked to imagine the hypothetical diagnosis were given to them. Arms A and B differed based on the order of terms used to describe the DCIS condition. Participants in arm A first received the term ‘abnormal cells’, while participants in arm B received the term ‘pre-invasive breast cancer cells’. Measures of concern and treatment preference for the hypothetical diagnosis were taken at this time point (time 1). Participants in both arms were then asked to imagine the same scenario with the alternative term used to describe DCIS and were again asked to indicate their level of concern and treatment preference (time 2). By switching the term within the arms, we were able to analyse the effect of changing the terminology both between participants and within participants.

Figure 1.

Study design.

Box 1. Description of ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) and treatment options*.

Initial terminology

Breast screening (mammograms) detects changes of cells in the breast as well as finding breast cancers. In some women these [abnormal cells/pre-invasive breast cancer cells] can progress to invasive cancer and in others they do not. It is estimated that, if left untreated, about one-third may progress to breast cancer over 10 years or more. That means that for about two-thirds of women these [abnormal cells/pre-invasive breast cancer cells] may not become cancer.

Imagine you had an abnormal breast screen and follow-up tests showed that there were [abnormal cells/pre-invasive breast cancer cells] found in your breast…

Treatment description

[Abnormal breast cells/ pre-invasive breast cancer cells] are usually treated by surgery, radiation or drugs, as in the case of breast cancer. Another approach is called watchful waiting, where doctors closely monitor the [abnormal cells/pre-invasive breast cancer cells] with regular mammograms and only treat if cells become more abnormal.

Alternative terminology

Thinking again about the previous scenario, if these [abnormal cells/pre-invasive breast cancer cells] in your breast were instead called [pre-invasive breast cancer cells/abnormal cells] (rather than [abnormal cells/pre-invasive breast cancer cells]).

*See online supplementary appendix 1 for the complete scenario and measures used.

Setting and participants

Participants were 269 Australian women aged 18 years and above, who spoke English as their main language at home.

The initial sample size calculation for the broader survey was performed with the objective of estimating proportions with acceptable precision for the entire sample. The sample of women used in this analysis provided at least 90% power to detect differences of 20% between any two proportions compared with a χ2 test and using a significance level of 0.05.

Procedures

The survey was carried out by the Social Research Centre (SRC), an independent research agency. A dual frame random digit dialling sample design was employed with a 50:50 split between landline and mobile samples. On calling the randomly selected telephone numbers, interviewers requested to speak with the person in the household aged 18 years or over who had the last birthday (landlines) or confirmed if the phone answerer was over 18 years of age (mobiles). Once a potential participant was established, interviewers provided information about the research purpose and process, and obtained informed consent. The total survey took approximately 15 min. Analysis of the DCIS scenario was conducted on female participants (n=269) only.

Measures

Participants were given the scenario as described, and asked their initial level of concern and their initial treatment preference between treatment (surgery, radiation or drugs) or watchful waiting. The terminology in each arm was then alternated and the outcomes (concern and treatment preferences) were assessed again (figure 1).

Time 1 measures

Concern: How concerned would you be about your result? Five-point Likert scale ranging from extremely concerned to not concerned at all.

-

Treatment preference: If research shows that watchful waiting is a safe and effective option, how do you think you would prefer to manage these abnormal cells/pre-invasive breast cancer cells?

Five-point response option scale: definitely prefer treatment, probably prefer treatment, prefer to do nothing, probably prefer watchful waiting (close monitoring by doctors), definitely prefer watchful waiting.

Time 2 measures

The following statement was read:

Thinking again about the previous scenario, if these abnormal cells/pre-invasive breast cancer cells were instead called pre-invasive breast cancer cells/abnormal cells [switched terminology],

Change in concern: Would you be more concerned or less concerned about your screening test result? Three-point response options: more concerned, no difference, less concerned.

Treatment preference: As above for time 1.

Analysis

Responses for level of concern were combined into three categories: extremely concerned, moderately concerned and not concerned/no opinion. Responses for treatment preferences were combined into two categories: prefer treatment and prefer watchful waiting. χ2 Tests were used to compare the level of concern and treatment preferences between arms based on the terminology given at each time point in the survey. The difference within groups regarding treatment options according to the change of terminology was tested using MacNemar’s test. There were a limited number of missing values with a maximum of 8% missing cases for a variable (see online supplementary appendix 2). We used a complete case analysis assuming missing completely at random. The significance level was set at 0.05 and the data were analysed using SPSS V.22.

Results

A total of 3307 telephone calls were made to recruit 500 survey participants. Of these, 1282 telephone numbers were eligible, 620 people agreed to participate and 500 participants (both men and women) completed the full survey with 282 women included in the initial analysis of the DCIS scenario. Thirteen women reported that they had had or currently have breast cancer, and were excluded, leaving a total of 269 women in the analysed sample (figure 2). The overall adjusted response rate for the survey was 48%. Participants were from a variety of demographic backgrounds, and varied in their experience with cancer screening and diagnosis (table 1), and included a higher proportion of women around breast screening and diagnostic age. Although the sample included a large proportion of women with low levels of education (48%), overall, the women in our study had slightly higher levels of education than those of the general Australian population.

Figure 2.

Participant recruitment. *Out of scope participants included persons under age 18 years, those whose main language spoken at home was not English and those who had a medical condition rendering them physically unable to complete the interview (DCIS, ductal carcinoma in situ).

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics

| Characteristic | Number of survey respondents, n=269 (%) |

|---|---|

| Age, years | |

| 18–29 | 36 (13.4) |

| 30–49 | 78 (29.0) |

| 50–69 | 109 (40.5) |

| ≥70 | 46 (11.1) |

| Education | |

| <High school | 44 (17.8) *(26.9) |

| Completed high school education only | 81 (30.1) *(38.7) |

| Bachelor degree/advanced diploma | 91 (33.8) *(26.5) |

| >Bachelor degree | 49 (18.2) *(7.7) |

| Experience with cancer screening | |

| Breast cancer | 173 (64.3) |

| Other forms of cancer | 144 (53.5) |

*Australian population data from the Australian Bureau of Statistics 2011 Census.

Concern about diagnosis

Initial concern (assessed at time 1)

As shown in table 2, initial concern was high in both arms with 47% of women across arms indicating they would be ‘extremely concerned’ and 48% ‘moderately concerned’ following a diagnosis of the condition described (DCIS). There were no statistically significant differences between arm A (‘abnormal cells’) and arm B (‘pre-invasive breast cancer cells’) for women, with 49% and 44%, respectively, indicating they would be ‘extremely concerned’, p=0.60 (table 2).

Table 2.

Women's level of concern and treatment preferences by terminology (n=269)

| Women randomised to |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total (n=269) (%) | Arm A ‘Abnormal cells’ first (n=141) (%) |

Arm B ‘Pre-invasive breast cancer cells’ first (n=128) (%) |

p value | |

| If presented with the initial terminology you would be | ||||

| Extremely concerned | 47 | 49 | 44 | |

| Moderately concerned | 48 | 45 | 51 | 0.60 |

| Not concerned/No opinion | 5 | 6 | 5 | |

| If presented with the alternative terminology you would be | ||||

| More concerned | 60 | 67 | 52 | |

| No difference | 24 | 15 | 35 | 0.001 |

| Less concerned | 16 | 18 | 13 | |

| If presented with the initial terminology you would | ||||

| Prefer treatment | 36 | 33 | 40 | 0.23 |

| Prefer watchful waiting | 64 | 67 | 60 | |

| If presented with the alternative terminology you would | ||||

| Prefer treatment | 43 | 45 | 41 | 0.51 |

| Prefer watchful waiting | 57 | 55 | 59 | 0.008* >0.99† |

*McNemar's test comparing the change in treatment preferences according to terminology used, for Arm A.

†McNemar's test comparing the change in treatment preferences according to terminology used, for Arm B.

Change in concern (assessed at time 2)

When the alternative term was used at time 2, the majority of women across arms stated they would be ‘more concerned’ (60%). However, women in arm A (initially given ‘abnormal cells’, then ‘pre-invasive breast cancer cells’ terminology) were significantly more likely to report increased concern than women in arm B who received information in the alternative order (67% vs 52%, p=0.001) (figure 3).

Figure 3.

Change in concern and treatment preference for women (n=269).

Treatment preferences

Initial treatment preferences (assessed at time 1)

Overall initial treatment preferences for watchful waiting were high (64%). There were no statistically significant differences in treatment preferences between arm A (‘abnormal cells’) and arm B (‘pre-invasive breast cancer cells’) for women (33% and 41% of women, respectively, favouring treatment, p=0.23).

Change in treatment preference (assessed at time 2)

There were within-group differences observed in the change in treatment preferences when terms were switched. Women in arm A were more likely to prefer treatment at time 2 when the terminology was switched from ‘abnormal cells’ to ‘pre-invasive breast cancer cells’, but there were no differences in arm B. In total, 18% of the women in arm A changed their preference to treatment when the terminology switched from ‘abnormal cells’ to ‘pre-invasive breast cancer cells’, while only 6% changed their preference to watchful waiting (p=0.008) (figure 3 and online supplementary appendix 3). No significant treatment preference changes were observed in arm B (9% vs 8%, p>0.99).

Discussion

In a randomised comparison of terms for DCIS among a national community sample of women, interest in watchful waiting was high irrespective of the terminology used. Changes in level of concern and treatment preferences were observed when terms with and without the word cancer were alternated. Women who received the ‘abnormal cells’ terminology first reported being significantly more concerned when given the alternative terminology (‘pre-invasive breast cancer cells’) at time 2. Women also indicated increased preferences for treatment when terminology was switched from ‘abnormal cells’ to ‘pre-invasive breast cancer cells’. This pattern was not observed when women were presented the terminology in the opposite order (cancer term first then ‘abnormal cells’ second). Overall, these findings suggest that terminology including the word cancer in a hypothetical scenario can influence level of concern and treatment preferences.

Although it has recently been stated that removal of the term cancer may reduce anxiety and desire for more invasive treatments,15–18 we could find only one research letter directly addressing this issue.19 That study of 394 women without breast cancer also found that women were more likely to choose surgery for treatment of DCIS when a cancer term (non-invasive cancer) was used compared with non-cancer terms breast lesion or abnormal cells. Forty-seven per cent of the women opted for surgery when the cancer term was used compared to 34% and 31% when the terms breast lesion and abnormal cells were used, respectively.19 In contrast to Omer, we did not find a difference in initial treatment preferences between the cancer and non-cancer terms; however, our study has important advantages in that it assessed the use of alternative terms within the same individuals and found a significant effect on both a psychological outcome (concern) and treatment preferences. Our study was conducted among a national community sample with a high proportion of older women from lower educational backgrounds. It is unclear how women in Omer's study were recruited, the response rate and whether they were a clinic or convenience sample. Their sample also included a higher proportion of adults with tertiary education and, indeed, high numeracy was found to be a predictor of treatment preferences in the study.

Women in our sample demonstrated higher levels of interest in watchful waiting. In addition to the demographic differences already described, this finding may be explained in part by different treatment options presented in each study: treatment (including medication) versus watchful waiting in our study in contrast to surgery, medication or active surveillance presented by Omer et al.

The overall level of concern to a hypothetical DCIS diagnosis was, not surprisingly, high. However, we had not anticipated the high level of interest in watchful waiting: 64% (initial treatment preference overall). The term watchful waiting was used in our questions to participants and it was also described as ‘close monitoring by doctors’. Importantly, the questions were explicitly predicated on the statement, ‘if research showed it to be a safe and effective option’, as has been shown in treatment for early stage prostate cancer20–22 and is currently being trialled for DCIS.23 24 In addition, it was clearly stated that the woman diagnosed could proceed to treatment (surgery, radiotherapy, medical management) in the future if needed, as would be the case in clinical practice. This was included following results from research by Gavaruzzi et al,25 which indicated greater endorsement for active treatment when watchful waiting excluded possible treatment in the future.

There were strengths as well as limitations to our study. First, our sample was a national community sample of women, which included a comparatively high proportion of women with lower levels of education (48%), that is, they either did not complete high school or had no post-high school qualifications (age 18 years). Women of all ages were included in the study since it is possible (although rare) for women outside the screening age to receive a diagnosis of DCIS. Our sample, however, did include a higher proportion of older women of screening age.

The study was limited by its hypothetical design as women facing a real diagnosis of DCIS may respond differently to participants in our survey. However, the experimental design allowed us to include participants who were unbiased by previous knowledge and information about DCIS, and enabled the use of standardised scenarios that could be directly compared. It is currently extremely difficult to test different terminologies among women diagnosed with DCIS (outside a clinical trial of watchful waiting for DCIS) since this needs to be a treatment option supported by clinicians. This may not be the case until rates of progression of DCIS to invasive cancer and the impact of watchful waiting is better established and understood through randomised controlled trials of this strategy.23 24 Testing women who have already received a diagnosis would not be meaningful since responses would be biased by their previous treatment decisions and the previous terminology used by clinicians. We also note that we gave participants an estimated population average for the risk of progression from DCIS to invasive cancer to ensure clarity and comprehension of the scenario. In practice, risk of progression is likely to vary according to age, tumour grade and other factors, and more individually tailored information would be given to patients. Furthermore, we note that the significant difference observed in arm A when terms were switched from non-cancer to cancer is unlikely to be a result of demand characteristics from the study design (with women feeling obliged to change their response). If this were the case, the same pattern would be expected in both randomised arms, but it was not observed in arm B. In addition, the changes we observed in arm A were in the same direction and consistent for both outcomes; concern and treatment preference.

There is growing concern about the problem of overdiagnosis and overtreatment of inconsequential disease. One strategy to mitigate this problem may be to change the terminology currently used to describe cancer-related conditions that have low malignant potential,15 such as DCIS. This could potentially encourage clinicians and patients to both opt for more conservative treatment strategies such as watchful waiting, although it would have to be part of a broader effort to support conservative treatment. Our research shows that a national sample of women demonstrated high levels of interest in watchful waiting, which has not previously been reported and supports the need for the two trials currently underway on this topic.23 24 Switching terminology from ‘abnormal cells’ to ‘pre-invasive breast cancer’ influenced women's concern and treatment preferences at least in a hypothetical setting. Together, the findings provide evidence that further investigation of the effects of changing DCIS terminology is needed in clinical populations as removing the cancer term may reduce concern and overtreatment, as proposed by Esserman et al.15 At minimum it shows that language is a powerful tool that has the potential to shape both understanding and actions.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the participants in our survey and the Social Research Centre (Kim Borg and Shane Compton).

Footnotes

Twitter: Follow Kirsten McCaffery @KirstenMcCaffer

Contributors: KM contributed to study design, data collection, analysis, interpretation, drafting and revising the manuscript. BN, RM, JH, AT-P, LI and AB contributed to study design, interpretation and revising the manuscript. All the authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding: This research was supported by a Program Grant awarded to the Screening and Test Evaluation Program (STEP; Number 633003) from the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC). KM is supported by an NHMRC Career Development Fellowship (Number 1029241). RM is supported by a Bond University Pro Vice Chancellor Scholarship.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: Ethical approval for the study was obtained through the Bond University Human Research Ethics Committee (RO 1765).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Wallis MG, Clements K, Kearins O et al. . The effect of DCIS grade on rate, type and time to recurrence after 15 years of follow-up of screen-detected DCIS. Br J Cancer 2012;106:1611–17. 10.1038/bjc.2012.151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts & Figures. Secondary Cancer Facts & Figures 2013. http://www.cancer.org/research/cancerfactsfigures/cancerfactsfigures/cancer-facts-figures-2013

- 3.Australian Institute of Health & Welfare. BreastScreen Australia monitoring report 2011–2012. October 2014.

- 4.Erbas B, Provenzano E, Armes J et al. . The natural history of ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast: a review. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2006;97:135–44. 10.1007/s10549-005-9101-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tuttle TM, Jarosek S, Habermann EB et al. . Increasing rates of contralateral prophylactic mastectomy among patients with ductal carcinoma in situ. J Clin Oncol 2009;27:1362–7. 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.1681 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gomez SL, Lichtensztajn D, Kurian AW et al. . Increasing mastectomy rates for early-stage breast cancer? Population-based trends from California. J Clin Oncol 2010;28:e155–7. 10.1200/JCO.2009.26.1032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Independent UK Panel on Breast Cancer Screening. The benefits and harms of breast cancer screening: an independent review. Lancet 2012;380:1778–86. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61611-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Esserman L, Shieh Y, Thompson I. Rethinking screening for breast cancer and prostate cancer. JAMA 2009; 302:1685–92. 10.1001/jama.2009.1498 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Partridge A, Winer JP, Golshan M et al. . Perceptions and management approaches of physicians who care for women with ductal carcinoma in situ. Clin Breast Cancer 2008;8:275–80. 10.3816/CBC.2008.n.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kennedy F, Harcourt D, Rumsey N. Perceptions of ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) among UK health professionals. Breast 2009;18:89–93. 10.1016/j.breast.2009.01.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fallowfield L, Matthews L, Francis A et al. . Low grade Ductal Carcinoma in situ (DCIS): how best to describe it? Breast 2014;23:693–6. 10.1016/j.breast.2014.06.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.De Morgan S, Redman S, White KJ et al. . “Well, have I got cancer or haven't I?” The psycho-social issues for women diagnosed with ductal carcinoma in situ. Health Expect 2002;5:310–8. 10.1046/j.1369-6513.2002.00199.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.De Morgan S, Redman S, D'Este C et al. . Knowledge, satisfaction with information, decisional conflict and psychological morbidity amongst women diagnosed with ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS). Patient Educ Couns 2011;84:62–8. 10.1016/j.pec.2010.07.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Esserman LJ, Thompson IM Jr, Reid B. Overdiagnosis and overtreatment in cancer: an opportunity for improvement. JAMA 2013;310:797–8. 10.1001/jama.2013.108415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Esserman LJ, Thompson IM, Reid B et al. . Addressing overdiagnosis and overtreatment in cancer: a prescription for change. Lancet Oncol 2014;15:e234–42. 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70598-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Allegra CJ, Aberle DR, Ganschow P et al. . NIH state-of-the-science conference statement: diagnosis and management of ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS). NIH Consens State Sci Statements 2009;26:1–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dunn BK, Srivastava S, Kramer BS. The word “cancer”: how language can corrupt thought. BMJ 2013;347:f5328 10.1136/bmj.f5328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Galimberti V, Monti S, Mastropasqua MG. DCIS and LCIS are confusing and outdated terms. They should be abandoned in favor of ductal intraepithelial neoplasia (DIN) and lobular intraepithelial neoplasia (LIN). Breast 2013;22:431–5. 10.1016/j.breast.2013.04.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Omer ZB, Hwang ES, Esserman LJ et al. . Impact of ductal carcinoma in situ terminology on patient treatment preferences. JAMA Intern Med 2013;173:1830–1. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.8405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hayes JH, Ollendorf DA, Pearson SD et al. . Active surveillance compared with initial treatment for men with low-risk prostate cancer: a decision analysis. JAMA 2010;304:2373–80. 10.1001/jama.2010.1720 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bul M, Zhu X, Valdagni R et al. . Active surveillance for low-risk prostate cancer worldwide: the PRIAS study. Eur Urol 2013;63:597–603. 10.1016/j.eururo.2012.11.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thomas I, Thrasher JB, Aus G et al. . Guideline for the management of clinically localized prostate cancer: 2007 update. J Urol 2007;177:2106–2131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Francis A, Fallowfield L, Rea D. The LORIS trial: addressing overtreatment of ductal carcinoma in situ. Clin Oncol 2015;27:6–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Elshof LE, Tryfonidis K, Slaets L et al. . Feasibility of a prospective, randomised, open-label, international multicentre, phase III, non-inferiority trial to assess the safety of active surveillance for low risk ductal carcinoma in situ—The LORD study. Eur J Cancer 2015;51:1497–510. 10.1016/j.ejca.2015.05.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gavaruzzi T, Lotto L, Rumiati R et al. . What makes a tumor diagnosis a call to action? On the preference for action versus inaction. Med Decis Making 2011;31:237–44. 10.1177/0272989X10377116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]