Abstract

Objectives

To identify the role of chronic comorbidities, considered together in a literature-validated index (Cumulative Illness Rating Scale, CIRS), and antibiotic or proton-pump inhibitor (PPI) treatments as risk factors for hospital-acquired Clostridium difficile infection (CDI) in elderly multimorbid hospitalised patients.

Design

Retrospective cohort study.

Setting

Subacute hospital geriatric care ward in Italy.

Participants

505 (238 male (M), 268 female (F)) elderly (age ≥65) multimorbid patients.

Main outcome measures

The relationship between CDI and CIRS Comorbidity Score, number of comorbidities, antibiotic, antifungal and PPI treatments, and length of hospital stay was assessed through age-adjusted and sex-adjusted and multivariate logistic regression models. The CIRS Comorbidity Score was handled after categorisation in quartiles.

Results

Mean age was 80.7±11.3 years. 43 patients (22 M, 21 F) developed CDI. The prevalence of CDI increased among quartiles of CIRS Comorbidity Score (3.9% first quartile vs 11.1% fourth quartile, age-adjusted and sex-adjusted p=0.03). In the multivariate logistic regression analysis, patients in the highest quartile of CIRS Comorbidity Score (≥17) carried a significantly higher risk of CDI (OR 5.07, 95% CI 1.28 to 20.14, p=0.02) than patients in the lowest quartile (<9). The only other variable significantly associated with CDI was antibiotic therapy (OR 2.62, 95% CI 1.21 to 5.66, p=0.01). PPI treatment was not associated with CDI.

Conclusions

Multimorbidity, measured through CIRS Comorbidity Score, is independently associated with the risk of CDI in a population of elderly patients with prolonged hospital stay.

Keywords: Multimorbidity, Clostridium difficile, Elderly, Proton pump inhibitors, Antibiotic

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Calculation of Cumulative Illness Rating Scale (CIRS) scores is a rapid, inexpensive way to determine the overall multimorbidity burden of elderly hospitalised patients.

The association of multimorbidity with Clostridium difficile infection has never been extensively studied in elderly multimorbid patients with prolonged hospital stay.

The retrospective study design may limit the generalisability of results.

Asymptomatic carriers of C. difficile were not identified.

Physical performance of patients and polypharmacy were not considered as potential confounders.

Introduction

Clostridium difficile infection (CDI) is one of the leading healthcare-associated infections in Western countries, responsible for diarrhoea and colitis in patients with abnormal gut microbiota and impaired local immunity.1 Even if the prevalence of community-acquired CDI is continuously rising,2 most cases occur in patients with prolonged hospitalisation, accounting for a rise in mortality and burden of healthcare costs.3

Systemic antibiotic therapy in the previous 30 days has been traditionally considered as the most important risk factor for CDI. Virtually, exposure to all types of antibiotics has been linked to an increased risk of CDI, with the highest ORs for cephalosporins, clindamycin and carbapenems.4 This risk is also consistently influenced by the timing and duration of antibiotic treatment.5

However, a significant number of hospital-acquired and community-acquired CDI occurs in patients without any recent antibiotic exposure in their personal history.6–8

As such, although widespread antibiotic use can increase environmental C. difficile contamination and thus the risk of infection also for those who are not on antibiotic treatment,7 alternative factors may be involved. Older age, cancer chemotherapy, inflammatory bowel disease, chronic kidney disease (CKD), organ transplantation, immunodeficiency and exposure to asymptomatic carriers or infected patients have all been recognised as independent risk factors.1 9 10 Chronic proton-pump inhibitor (PPI) therapy may also be associated with CDI,11 even if some studies have questioned the strength of this independent association.12

Since most hospital-acquired cases of CDI occur in oldest-old patients with a high burden of chronic comorbidities affecting multiple organs and systems,13 multimorbidity itself may play a relevant role in defining the risk of CDI.14 Multimorbidity scores have been demonstrated as useful tools for predicting the risk of severe hospital-acquired infections by other multidrug-resistant bacteria.15 16

Therefore, the aim of this retrospective hospital-based study is to evaluate the risk factors of CDI in a cohort of multimorbid, hospitalised elderly patients with a prolonged hospital stay. We focus on the possible role of Cumulative Illness Rating Scale (CIRS) Comorbidity Score, a literature-validated17 index particularly useful in defining the prognostic trajectory of geriatric-hospitalised patients.18

Methods

All clinical records of patients admitted to the Critical Subacute Care Unit of Parma University Hospital, Northern Italy, from 1 January to 30 June 2013 were analysed by using a retrospective cohort study design. This unit is an internal medicine ward primarily devoted to elderly multimorbid patients requiring prolonged hospital stay for critical conditions. Admission is generally planned after some days of hospital stay in other acute care medical or surgical wards.

Inclusion criteria for this study were age ≥65 years, absence of a well-defined terminal condition with a survival prognosis <30 days, presence of at least two of the following criteria: reduced muscular strength, reduced gait speed, forced bed rest, lack of autonomy in activities of daily living, >5% weight loss in the previous 6 months.

CDI was defined according to the presence of at least one stool sample with a laboratory confirmation of positive C. difficile toxin assay in a patient with diarrhoea or visualisation of pseudomembranes on colonoscopic examination. Diarrhoea was defined as three or more loose bowel movements per day, with no other known cause. All other patients fulfilling the eligibility criteria were considered as CDI negative.

The cumulative incidence of CDI in our unit, according to data from Healthcare Hospital Direction, consisted of 8 cases per 100 patients in 2013, with 1432 unit-admissions in the same year. Therefore, we considered 6 months (January–June 2013) as a sufficient time period of observation to reach the target number of 452 patients, and in order to achieve an absolute precision of 2.5% and a confidence level of 95%.

For each patient, the following variables were considered for possible association with CDI: age, sex, hospital stay before transferral to our unit, total length of stay, antibacterial, antifungal and PPI treatment, CIRS Comorbidity Score, overall number of comorbidities. Presence of specific comorbidities (including cardiovascular disease, respiratory disease, dementia, stroke, cancer, CKD, liver disease) and in-hospital death were also recorded. CIRS is a tool validated in the scientific literature for geriatric hospitalised patients.17 The calculated score ranging from 0 to 4 is the result of disease severity for each of 14 items representing possible organs affected by a chronic disease. The CIRS Comorbidity Score is the sum of all scores assigned to 14 items. The CIRS Severity Index is the number of items ranking three or four in disease severity. All the considered variables were collected from clinical records of eligible patients. The CIRS Comorbidity Score was calculated for each patient at the time of admission to our ward and recorded in clinical records. Participants with missing data in clinical records were not considered for final analysis.

Variables were reported as number and percentage, mean±SD or, for not normally skewed distributions, median and IQR. Characteristics of patients were compared across CDI positivity and negativity using Kruskal-Wallis tests for continuous variables, after adjustment for age and sex. Logistic regression models were used to examine the relationship between CIRS Comorbidity Score after stratification in quartiles and the risk of having CDI. Logistic regression models were adjusted for age and sex (model 1). The relationship between quartiles of CIRS Comorbidity Score and CDI was also adjusted for other variables that were significant in the univariate analysis (model 2). Since antibiotic treatment is the most common and powerful risk factor for CDI, an additional analysis was also performed after categorising patients according to exposure to antibiotic treatment to better test the association between CIRS Comorbidity Score and CDI. All analyses were performed using the SAS statistical package, V.9.1 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, North Carolina, USA) with a type I error of 0.05.

This study was carried out without any extra-institutional funding. All the clinical investigations were performed according to the principles expressed in the Declaration of Helsinki. Given the retrospective design of the study, specific informed consent was obtained, according to Italian law.

Results

The total number of patients admitted to the subacute care ward from January to June 2013 was 633 (298 male (M), 335 female (F)). In total, 128 of them (60 M, 68 F) were excluded from the study for not meeting the inclusion criteria (120 patients, 56 M, 64 F) or for missing CIRS scores in clinical records (8 patients, 4 M, 4 F). The remaining 505 patients (238 M, 267 F, mean age 81±10 years) were considered for statistical analysis. The general characteristics of 505 patients are summarised in table 1. The most frequent chronic comorbidities were cardiovascular disease (55%), respiratory disease (44%), dementia (43%) and stroke (30%). Exposure to PPI, systemic antibacterial and antifungal treatment in the whole cohort were 87%, 44% and 13%, respectively. The in-hospital mortality rate was 22%.

Table 1.

Main features of the population studied (n=505)

| Age, years | 80.7±11.3 |

| Men | 47 (238/505) |

| Mean hospital stay before transferral to our unit, days | 20.8±19.8 |

| Mean length of stay in our unit, days | 15.5±11.9 |

| Mean total length of stay, days | 36.2±24.3 |

| Death | 22 (108/505) |

| Infection (Clostridium difficile excluded) | 62 (313/505) |

| Cardiovascular disease | 55 (278/505) |

| Respiratory disease | 44 (222/505) |

| Dementia | 43 (216/505) |

| Stroke | 30 (150/505) |

| Cancer | 25 (126/505) |

| Chronic kidney disease | 24 (122/505) |

| Liver disease | 9 (48/505) |

| C. difficile infection | 8.5 (43/505) |

| PPI treatment | 87 (434/505) |

| Antibacterial treatment | 44 (223/505) |

| Antifungal treatment | 13 (67/505) |

Data are reported as percentage (number) or mean±SD whenever appropriate.

PPI, proton-pump inhibitor.

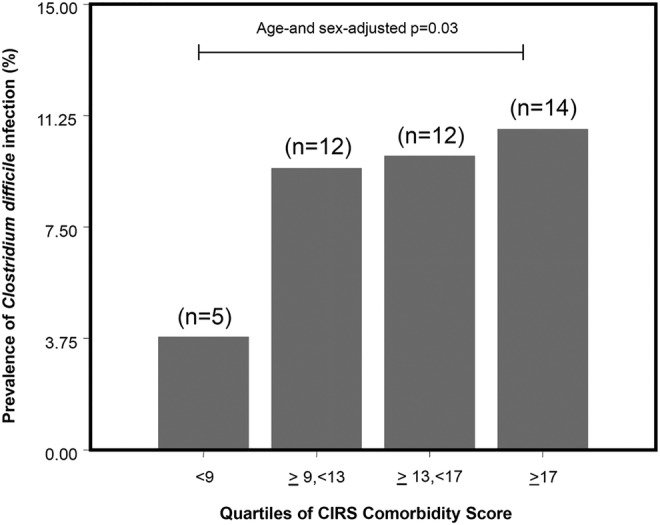

Forty-three patients of the 505 (22 M, 21 F, 8.5%) were classified as CDI positive according to the criteria exposed above. The other 462 patients were therefore classified as CDI negative. The prevalence of CDI by quartile of CIRS Comorbidity Score is shown in figure 1. Age-adjusted and sex-adjusted tests for linear trend showed a significant association between CDI and quartiles of CIRS Comorbidity Score (p=0.03).

Figure 1.

Prevalence of Clostridium difficile infections after quartile categorisation of Cumulative Illness Rating Scale (CIRS) Comorbidity Score in the studied population (n=505).

Table 2 shows a comparison between CDI-positive and CDI-negative patients for all other considered covariates. Notably, CDI-positive patients had significantly higher rates of antibacterial and antifungal therapy and longer hospital stays. PPI treatment did not significantly differ between the two groups.

Table 2.

Comparison between general characteristics of CDI-positive and CDI-negative patients

| CDI positive (N=43) | CDI negative (N=462) | p Value* | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 82.6±8.5 | 80.4±10.4 | 0.20 |

| Men | 22 (51.2) | 216 (46.8) | 0.41 |

| Mean hospital stay before transferral to our unit, days | 23±18 | 21±20 | 0.43 |

| Mean length of stay in our unit, days | 30±16 | 14±11 | 0.02 |

| Mean total length of stay, days | 53±28 | 35±27 | 0.03 |

| Number of comorbidities | 3 (3–5) | 3 (2–4) | 0.01 |

| PPI treatment | 40 (93) | 394 (85.8) | 0.19 |

| Antibacterial treatment | 31 (72.1) | 192 (41.6) | <0.001 |

| Antifungal treatment | 10 (23.3) | 57 (12.3) | 0.03 |

| Cardiovascular disease | 23 (53.5) | 255 (55.2) | 0.55 |

| Respiratory disease | 20 (46.5) | 202 (43.7) | 0.91 |

| Dementia | 23 (53.5) | 193 (41.7) | 0.21 |

| Stroke | 17 (39.5) | 133 (28.8) | 0.18 |

| Cancer | 8 (18.6) | 117 (25.4) | 0.40 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 16 (37.2) | 106 (22.9) | 0.05 |

| Liver disease | 7 (16.3) | 41 (8.9) | 0.09 |

Statistically significant differences (p≤0.05) are indicated in bold.

Data are reported as number (%), mean±SD or median (IQR) whenever appropriate.

*Age-adjusted and sex-adjusted when appropriate.

CDI, Clostridium difficile infection; PPI, proton-pump inhibitor.

In the age-adjusted and sex-adjusted logistic regression model (table 3, model 1), patients in the highest quartile of CIRS Comorbidity Score (values ≥17) carried out a significantly higher risk of CDI, as compared with those in the lowest quartile (values <9) (OR 2.89, 95% CI 1.02 to 8.54, p=0.045). This relationship was also confirmed in the multivariable logistic regression model (model 2), shown in table 3 (OR for highest vs lowest quartile 5.07, 95% CI 1.28 to 20.14, p=0.02). The only other factor significantly associated with CDI was the antibacterial therapy (OR 2.61, 95% CI 1.21 to 5.64, p=0.01) (table 3). An alternative multivariable logistic regression model including the number of comorbidities instead of CIRS Comorbidity Score is shown in the online supplementary material.

Table 3.

Factors associated with a higher risk for Clostridium difficile infection at age-adjusted and sex-adjusted (model 1) and multivariate (model 2) logistic regression models

| OR | 95% CI | p Value* | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 (age-adjusted and sex-adjusted) | |||

| CIRS Comorbidity Score | |||

| First quartile (<9) | – | – | – |

| Second quartile (≥9, <13) | 2.49 | 0.84 to 7.42 | 0.10 |

| Third quartile (≥13, <17) | 2.54 | 0.85 to 7.64 | 0.09 |

| Fourth quartile (≥17) | 2.89 | 1.02 to 8.54 | 0.045 |

| Age | 1.01 | 0.97 to 1.05 | 0.47 |

| Sex (female vs male) | 0.78 | 0.41 to 1.49 | 0.45 |

| Model 2 (fully adjusted) | |||

| CIRS Comorbidity Score | |||

| First quartile (<9) | – | – | – |

| Second quartile (≥9, <13) | 3.50 | 0.48 to 25.38 | 0.22 |

| Third quartile (≥13, <17) | 2.55 | 0.85 to 7.68 | 0.09 |

| Fourth quartile (≥17) | 5.07 | 1.28 to 20.14 | 0.02 |

| Antibacterial therapy | 2.61 | 1.21 to 5.64 | 0.01 |

| Antifungal therapy | 1.54 | 0.67 to 3.53 | 0.31 |

| Age | 1.03 | 0.98 to 1.07 | 0.21 |

| Sex (female vs male) | 0.67 | 0.34 to 1.33 | 0.26 |

| Mean length of stay in our unit | 1.02 | 0.99 to 1.02 | 0.14 |

| Mean total length of stay | 1.05 | 0.99 to 1.02 | 0.43 |

CIRS, Cumulative Illness Rating Scale.

*Statistically significant differences (p≤0.05) are indicated in bold.

To explore the relationship between multimorbidity measured through CIRS Comorbidity Score and CDI, a further analysis was performed categorising patients according to exposure to antibiotics (223 patients with antibiotics, of whom 31 were CDI positive, and 282 patients without antibiotics, of whom 12 were CDI positive). The CIRS Comorbidity Score was significantly higher in CDI-positive patients only in the antibiotics-treated group (median CDI positive 15, IQR 12 to 18, vs median CDI negative 12, IQR 8 to 17, p=0.016).

Discussion

This study shows that, in a cohort of elderly patients with prolonged hospital stay, multimorbidity is significantly and independently associated with CDI onset, especially for those who have a very high number of chronic comorbidities (ie, those who have a CIRS Comorbidity Score ≥17). Antibiotic therapy is confirmed to be an independent risk factor for CDI in our cohort.

Our study has several limitations. First, even if the considered cohort has a high burden of multimorbidity and a high incidence of CDI, the retrospective design did not allow us to explore the contribution of single diseases and C. difficile colonisation status in defining the risk of CDI.19 Second, no phenotypical characterisation of C. difficile strains is provided, while the risk of CDI at least partly depends on microbe-related factors.20 Moreover, information on other factors recently associated with risk of CDI, such as polypharmacy, notably exposure to antidepressants, opioids and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and functional status,21–24 was not available in this cohort.

Despite previous reports stating that CIRS Comorbidity Score is associated with overall comorbidity burden and prognosis in hospitalised elderly patients,18 its narrow range of values may not be sufficiently accurate for describing clinical complexity in our cohort. As shown in table 3, only CIRS Comorbidity Score in the top quartile (≥17) was significantly associated with CDI, as compared with those patients in the first quartile (<9). Thus, multimorbidity exerts an additional contribution to a lesser extent than antibiotic therapy in defining the risk of CDI.

Very few studies have explored the association between multimorbidity and CDI and, to the best of our knowledge, none has assessed it through CIRS. The information on CIRS is perhaps the main strength of the present study. Moreover, the focus on a population of elderly patients with prolonged hospital stay allows one to understand the contribution of other risk factors besides antibiotic therapy exactly on those patients who more frequently develop CDI.13 Interestingly, a recent study carried out with a geriatric methodology and considering multimorbidity in a literature-validated index (Charlson score) failed to demonstrate a significant correlation between this parameter and CDI onset and severity. Moreover, the cohort considered for the final analysis consisted also of patients younger than 65 years.24 However, in other reports, the Charlson score was proven to be a significant determinant of an adverse outcome in patients with hospital-acquired CDI.25 26 Stevens et al14 recently demonstrated that a multimorbidity index specifically designed for infectious disease investigations (chronic disease score-infectious disease, CDS-ID) is a significant predictor of CDI in a large retrospective cohort of adult inpatients. However, this research did not focus on high-risk patients (ie, geriatric patients admitted to an internal medicine ward and with prolonged hospital stay) but included all patients admitted to a third-level specialty care hospital who received at least 2 days of antibiotic treatment. Moreover, unlike CIRS, CDS-ID takes into account only some potential conditions, namely peptic ulcer disease, kidney disease, diabetes, cancer, respiratory illness, organ transplant and not the complex broad spectrum of disease that may coexist in geriatric patients with complex health needs.15 However, our results seem to confirm that multimorbidity also plays a relevant role in a geriatric setting.

It is noteworthy that in our cohort 12 CDI-positive patients of the 43 were not exposed to previous antibiotic treatment. In this case, it is plausible that the crucial factor for infection onset is the high level of ward antibiotic use that may have increased the environmental contamination and ecological pressure.7 Thus, multimorbidity may play only a secondary role.

PPI exposure was not associated with CDI onset, and these data are consistent with most of the recent literature.12 However, the widespread use of these drugs in our cohort (86.5%) may represent a possible bias and questions the potential inappropriateness of PPI prescription in this specific setting of older patients. A recent Italian multicentre study conducted in internal medicine wards has shown that PPI administration is unjustified in 62% of cases, highlighting the need for thorough medication revision both at hospital admission and discharge.27 Moreover, in the oldest-old patients, the prevalence of atrophic gastritis is very high, thus making gastric acid suppression virtually useless.28

In conclusion, multimorbidity may represent an additional risk factor for CDI onset in elderly patients with prolonged hospital stay, alongside with antibiotic treatment. The CIRS Comorbidity Score may be a useful tool to estimate this additional risk, especially in patients who undergo long-term antibiotic treatment. Since elderly patients are nowadays those who most frequently develop CDI, further studies are needed to explore the association between this infection and the domains of multimorbidity, frailty and polypharmacy, which are intrinsic features of geriatric patients admitted to hospital. A precise definition of risk factors, other than antibiotic therapy, involved in CDI will allow one to adopt effective preventive measures in order to limit the increasing CDI-related health costs.29

Footnotes

Contributors: AT and AN were responsible for the study concept and design and drafting and critical revision of the manuscript. GF was responsible for statistical analysis and interpretation of data. BP, IM and LG were responsible for data collection, interpretation and critical revision of the manuscript. FT, MV, MM and TM were responsible for the study concept and design and critical revision of the manuscript. FL was responsible for statistical analysis, interpretation of data and critical revision of the manuscript.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: The study protocol was approved by the local ethics committee (Comitato Etico per Parma, ID 10739).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Leffler DA, Lamont JT. Clostridium difficile infection. N Engl J Med 2015;372:1539–48. 10.1056/NEJMra1403772 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lessa FC, Mu Y, Bamberg WM et al. Burden of Clostridium difficile infection in the United States. N Engl J Med 2015;372:825–34. 10.1056/NEJMoa1408913 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lofgren ET, Cole SR, Weber DJ et al. Hospital-acquired Clostridium difficile infections. Estimating all-cause mortality and length of stay. Epidemiology 2014;25:570–5. 10.1097/EDE.0000000000000119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Slimings C, Riley TV. Antibiotics and hospital-acquired Clostridium difficile infection: update of systematic review and meta-analysis. J Antimicrob Chemother 2014;69:881–91. 10.1093/jac/dkt477 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brown KA, Fisman DN, Moineddin R et al. The magnitude and duration of Clostridium difficile infection risk associated with antibiotic therapy: a hospital cohort study. PLoS ONE 2014;9:e105454 10.1371/journal.pone.0105454 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barletta JF, Sclar DA. Proton pump inhibitors increase the risk for hospital-acquired Clostridium difficile infection in critically ill patients. Crit Care 2014;18:714 10.1186/s13054-014-0714-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brown K, Valenta K, Fisman D et al. Hospital ward antibiotic prescribing and the risks of Clostridium difficile infection. JAMA Intern Med 2015;175:626–33. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.8273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Khanna S, Pardi DS, Aronson SL et al. The epidemiology of community-acquired Clostridium difficile infection: a population-based study. Am J Gastroenterol 2012;107:89–95. 10.1038/ajg.2011.398 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wilcox MH, Mooney L, Bendall R et al. A case-control study of community-associated Clostridium difficile infection. J Antimicrob Chemother 2008;62:388–96. 10.1093/jac/dkn163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chitnis AS, Holzbauer SM, Belflower RM et al. Epidemiology of community-associated Clostridium difficile infection, 2009 through 2011. JAMA Intern Med 2013;173:1359–67. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.7056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dial S, Delaney JA, Barkun AN et al. Use of gastric acid-suppressive agents and the risk of community-acquired Clostridium difficile-associated disease. JAMA 2005;294:2989–95. 10.1001/jama.294.23.2989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Novack L, Kogan S, Gimpelevich L et al. Acid suppression therapy does not predispose to Clostridium difficile infection: the case of the potential bias. PLoS ONE 2014;9:e110790 10.1371/journal.pone.0110790 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mellace L, Consonni D, Jacchetti G et al. Epidemiology of Clostridium difficile-associated disease in internal medicine wards in Northern Italy. Intern Emerg Med 2013;8:717–23. 10.1007/s11739-012-0752-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stevens V, Concannon C, van Wijngaarden E et al. Validation of the chronic disease score-infectious disease (CDS-ID) for the prediction of hospital-associated Clostridium difficile infection (CDI) within a retrospective cohort. BMC Infect Dis 2013;13:150 10.1186/1471-2334-13-150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McGregor JC, Kim PW, Perencevich EN et al. Utility of Chronic Disease Score and Charlson Comorbidity Index as comorbidity measures for use in epidemiologic studies of antibiotic-resistant organisms. Am J Epidemiol 2005;161:483–93. 10.1093/aje/kwi068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nouvenne A, Ticinesi A, Lauretani F et al. Comorbidities and disease severity as risk factors for carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae colonization: report of an experience in an internal medicine unit. PLoS ONE 2014;9:e110001 10.1371/journal.pone.0110001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Salvi F, Miller MD, Grilli A et al. A manual of guidelines to score the modified Cumulative Illness Rating Scale and its validation in acute hospitalized elderly patients. J Am Geriatr Soc 2008;56:1926–31. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.01935.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zekry D, Loures Valle BH, Lardi C et al. Geriatrics index of comorbidity was the most accurate predictor of death in geriatric hospital among six comorbidity scores. J Clin Epidemiol 2010;63:1036–44. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.11.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Alasmari F, Seiler SM, Hink T et al. Prevalence and risk factors for asymptomatic Clostridium difficile carriage. Clin Infect Dis 2014;59:216–22. 10.1093/cid/ciu258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Loo VG, Bourgault AM, Poirier L et al. Host and pathogen factors for Clostridium difficile infection and colonization. N Engl J Med 2011;365:1693–703. 10.1056/NEJMoa1012413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rogers MA, Greene MT, Young VB et al. Depression, antidepressant medications, and risk of Clostridium difficile infection. BMC Med 2013;11:121 10.1186/1741-7015-11-121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Suissa D, Delaney JA, Dial S et al. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and the risk of Clostridium difficile-associated disease. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2012;74:370–5. 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2012.04191.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mora AL, Salazar M, Pablo-Caeiro J et al. Moderate to high use of opioid analgesics are associated with an increased risk of Clostridium difficile infection. Am J Med Sci 2012;343: 277–80. 10.1097/MAJ.0b013e31822f42eb [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rao K, Micic D, Chenoweth E et al. Poor functional status as a risk factor for severe Clostridium difficile infection in hospitalized older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 2013;61:1738–42. 10.1111/jgs.12442 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rodriguez-Pardo D, Almirante B, Bartolomé RM et al. , Barcelona Clostridium difficile Study Group. Epidemiology of Clostridium difficile infection and risk factors for unfavorable clinical outcomes: results of a hospital-based study in Barcelona, Spain. J Clin Microbiol 2013;51:1465–73. 10.1128/JCM.03352-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hardt C, Berns T, Treder W et al. Univariate and multivariate analysis of risk factors for severe Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea: importance of co-morbidity and serum C-reactive protein. World J Gastroenterol 2008;14:4338–41. 10.3748/wjg.14.4338 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pasina L, Nobili A, Tettamanti M et al. Prevalence and appropriateness of drug prescriptions for peptic ulcer and gastro-esophageal reflux in a cohort of hospitalized elderly. Eur J Intern Med 2011;22:205–10. 10.1016/j.ejim.2010.11.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Goni E, Caleffi A, Nouvenne A et al. Gastric function assessed by Gastropanel® in very old patients (over 80 years old) and appropriateness of PPI administration. Helicobacter 2014;19(Suppl 1):166. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Eckmann C, Wasserman M, Latif F et al. Increased hospital length of stay attributable to Clostridium difficile infection in patients with four co-morbidities: an analysis of hospital episode statistics in four European countries. Eur J Health Econ 2013; 14:835–46. 10.1007/s10198-013-0498-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]