Abstract

Objectives

To evaluate 3 pilot chlamydia retesting programmes in South West England which were initiated prior to the release of new National Chlamydia Screening Programme (NCSP) guidelines recommending retesting in 2014.

Methods

Individuals testing positive between August 2012 and July 2013 in Bristol (n=346), Cornwall (n=252) and Dorset (n=180) programmes were eligible for inclusion in the retesting pilots. The primary outcomes were retest within 6 months (yes/no) and repeat diagnosis at retest (yes/no), adjusted for area, age and gender.

Results

Overall 303/778 (39.0%) of participants were retested within 6 months and 31/299 (10.4%) were positive at retest. Females were more likely to retest than males and Dorset had higher retesting rates than the other areas.

Conclusions

More than a third of those eligible were retested within the time frame of the study. Chlamydia retesting programmes appear feasible within the context of current programmes to identify individuals at continued risk of infection with relatively low resource and time input.

Keywords: EPIDEMIOLOGY

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study reflects the experience of local areas in implementing new guidance on retesting for chlamydia within the context of the existing National Chlamydia Screening Programme.

Delivering retesting appears feasible and is likely to diagnose reasonable numbers of additional infections (10% of those retested within the pilot were infected).

The study is limited mainly because the interventions were not standardised across the study sites.

Introduction

Chlamydia is the most commonly diagnosed bacterial sexually transmitted infection (STI) in the UK. In England, the National Chlamydia Screening Programme (NCSP) was piloted in 2003 and implemented nationally in 2008.1 The NCSP recommends that sexually active young men and women aged <25 years are tested for chlamydia annually and on change of sexual partner. In 2013, in England, over 1.7 million chlamydia tests were performed, equating to 25% coverage in 15–24-year.olds. Nationally 14 000 diagnoses of chlamydia were made, positivity 8.1%. Women are tested more than men, with 69% of tests occurring in women.2 Case management of positives includes: antibiotic treatment, partner notification support and provision of safer sex advice. In August 2013, the English NCSP recommended routine offer of a retest for all chlamydia-positive adults after 3 months.3 Prior to this, there was no specific recommendation regarding retesting, although individuals would be offered tests opportunistically at any attendance and are free to seek testing at any time. Individuals who test positive for chlamydia are at an increased risk of subsequently testing positive compared with those who initially test negative.4 Repeat infections are associated with an increased risk of pelvic inflammatory disease and other long-term reproductive sequelae.5

The most effective or cost-effective way to deliver a chlamydia retesting programme within the NCSP context is not known, and local areas need to determine how best to implement the new guidelines within their local system.1 A recent systematic review of active recall for STI and HIV testing found that active recall increased reattendance or retesting in 13 of 14 studies.6 Home sampling and SMS reminders appeared to increase retesting, but the range was wide and the evidence limited by study heterogeneity.6 An earlier study in Cornwall showed that individuals testing positive were more than twice as likely to retest positive than those testing negative (19.4% vs 7.2%).7 In 2012, following the NCSP workshop and consultation about a change in recommendations, pilot retesting programmes were implemented in three areas; Bristol (Avon), Cornwall and Dorset. (Note: Avon refers to the Bristol chlamydia screening office, which covered the Avon area of Bristol, North Somerset, South Gloucestershire and Bath and North East Somerset (BANES) as in previous Primary Care Trust (PCT) organisational structure.) In this study we present an evaluation of these three retest pilot programmes to assess what retest rates and positivity can realistically be expected when retesting is implemented nationally.

Methods

Study population: All individuals who tested positive for chlamydia at their initial visit were eligible for inclusion.

Settings: All three sites are located in South West England. The Bristol site included Bristol city and the surrounding area (Avon). Bristol city is a large, urban centre, with large black ethnic minority population and significant areas of high deprivation and has the highest test volume and population. The surrounding area is rural/suburban. Dorset is a rural, affluent county including the county town of Dorchester. Cornwall is a large, rural county on the South Western peninsula of England. Chlamydia tests in all areas are offered by a variety of service providers with different models of access: genitourinary medicine clinics (GUM), sexual and reproductive health clinics, family planning services, general practice (GP), pharmacies and young peoples’ services such as Brook clinics all offer chlamydia testing. We chose these areas to broadly reflect the range of practice nationally. The delivery of NCSP is locally devolved, and so organisation of chlamydia screening nationally is very heterogeneous and reflects local demography, geography and population needs as well as historical organisation of services.

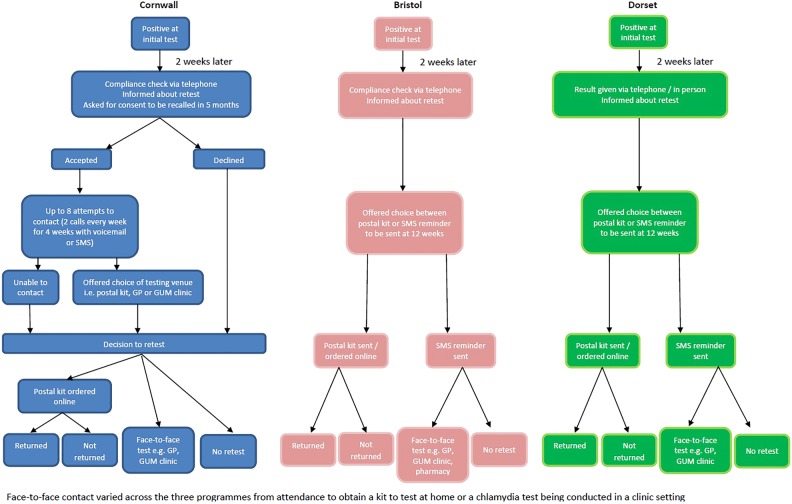

Each area determined locally how to conduct the pilot to fit with their current organisation of screening and patient management (illustrated in figure 1), therefore did not require consistency of scripting in phone calls or text message content. Furthermore, some areas modified their approach in response to user feedback or their experiences. While this reduces the comparability and reproducibility of these pilots, we nonetheless feel it is important to report the experience and outcomes that were achieved in a ‘real-life’ implementation setting.

Figure 1.

Resting pathway followed in each area (GP, general practice; GUM, genitourinary medicine clinics).

Outcomes: Number retested within 6 months and more than 2 weeks after primary test (yes/no) and number reinfected at retest (yes/no). Outcomes were adjusted for age (15–19, 20–25), gender and area of study (Bristol, Dorset, Cornwall).

Study design

In each area, individuals were contacted routinely 2 weeks after their initial visit either to check compliance with their treatment (Bristol and Cornwall) or to discuss their result (Dorset). During this encounter, individuals were informed about their risk of retesting positive and recommended to retest (figure 1). In Bristol and Cornwall, this compliance check was via telephone, and in Dorset, they were either contacted by telephone or seen in clinic to discuss results. In Bristol and Cornwall, the pilots were run by the chlamydia screening office, whereas in Dorset, it was run by the genitourinary (GUM) clinic. Data were collected on age, gender, date of treatment, date and result of retest, whether a postal kit was sent and returned and number of contact attempts. Postal kits contained full instructions to collect urine or vaginal swab and contained a freepost return envelope to return tests to the laboratory.

In Cornwall, individuals were asked for consent to be contacted and recalled in 5 months. If they gave consent a note was made in their records, and up to eight attempts to contact were made (2 calls every week for 4 weeks with a voicemail or SMS, depending on patient preference). If contact was made (patient answered or called back), they were offered a choice of postal testing kit or advised to attend GUM clinic or GP. Individuals were followed up to see if a retest was undertaken and a record of any retests, the result and the venue was made. Individuals who did not wish to be contacted or who could not be contacted remained eligible for the study since they were advised to retest at 3 months, but did not receive a reminder. In Bristol and Dorset, individuals were simply asked if they would prefer to be sent a postal kit or an SMS reminder at 12 weeks. No discussion around consent to be recalled occurred in Bristol or Dorset. In Bristol and Dorset, those that opted for a postal kit were sent it at 12 weeks, which was also accompanied by an SMS reminder in Bristol. Those who did not want to be sent a postal kit were just sent an SMS reminder either to contact the screening office or make an appointment at the GUM clinic. Only one SMS reminder was sent in Bristol and Dorset (compared with multiple attempts in Cornwall). For each individual, it was recorded if a postal kit was sent and whether it was returned, whether they retested via an alternative route (with details if known) and what the results of any retests were.

Each area provided a data set of individuals testing positive during 6–8 months between August 2012 and July 2013 who were then followed up for a further 6 months to assess whether they were retested and the result of the retest. The raw data from each area were standardised and collated in an Excel spreadsheet (provided as pdf in online supplementary material, Supplementary_individual_level_data.pdf). Patient identifiable data (name, date of birth or postcode) were removed and each individual was given a study ID prior to analysis. Individuals were excluded from the analysis if they were older than 25 years of age or younger than 15 or if the information collected was incomplete.

For Cornwall analyses of retesting rates according to (1) the number of attempts to contact individuals and (2) whether or not consent to be recalled was given, were also conducted.

We used logistic regression to analyse the primary outcomes of retesting and positivity at retest. This was done in STATA V.13.1 StatCorp. We describe the retesting pathways in online supplementary appendix 1. No ethical approval was sought as this was a modification of current practice and data were anonymised.

In order to provide a benchmark for self-selected retesting in the absence of a specific retest guideline, we looked back at data previously collected in Cornwall.4 For those tested during the first half of 2008 (January–June), we calculated the number who were retested within 6 months and the proportion positive and negative at first and second test. Comparable data were not available for Dorset or Bristol.

Results

During the study period (August 2012–July 2013), data were collected on 862 individuals testing positive for chlamydia.

Data cleaning

Individuals were excluded if aged under 15 years, over 25 years or if records were incomplete. Cornwall: there were no exclusions giving 252 records included. Bristol: out of 377 records eligible for inclusion, 5 were excluded as patient/outcome details incomplete and 26 excluded as over 25 years old leaving 346 records included. Dorset: out of 243 records eligible for inclusion, 5 were excluded as details incomplete, 1 excluded as <15 years old and 57 were excluded as over 25 years old leaving 180 records included. This gave a total of 778 records of individuals diagnosed with chlamydia eligible for inclusion in the study across the three areas (Bristol 346, Cornwall 252, Dorset 180). The results are summarised in table 1. Most participants were female (68.8%) with a mean age of 21 years.

Table 1.

Summary of retesting study participants (age, gender and area): with number and percentage retested and rediagnosed in Cornwall, Bristol and Dorset, England, August 2012–July 2013

| Area | Gender | Age | N | N retested | Percentage retested | Confirmed result | Positive | Percentage positive |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bristol | Female | 15–19 | 79 | 32 | 40.5 | 31 | 4 | 12.9 |

| 20–25 | 167 | 74 | 44.3 | 73 | 7 | 9.6 | ||

| Subtotal (gender) | 246 | 106 | 43.1 | 104 | 11 | 10.6% | ||

| Male | 15–19 | 14 | 2 | 14.3 | 2 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| 20–25 | 86 | 22 | 25.6 | 20 | 2 | 10.0 | ||

| Subtotal (gender) | 100 | 24 | 24.0 | 22 | 2 | 9.1 | ||

| Subtotal (area) | 346 | 130 | 37.6 | 126 | 13 | 10.3 | ||

| Cornwall | Female | 15–19 | 53 | 24 | 45.3 | 24 | 1 | 4.2 |

| 20–25 | 142 | 60 | 42.3 | 60 | 9 | 15.0 | ||

| Subtotal (gender) | 195 | 84 | 43.1 | 84 | 10 | 11.9 | ||

| Male | 15–19 | 7 | 1 | 14.3 | 1 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| 20–25 | 50 | 7 | 14.0 | 7 | 1 | 14.3 | ||

| Subtotal (gender) | 57 | 8 | 14.0 | 8 | 1 | 12.5 | ||

| Subtotal (area) | 252 | 92 | 36.5 | 92 | 11 | 12.0 | ||

| Dorset | Female | 15–19 | 37 | 24 | 64.9 | 24 | 2 | 8.3 |

| 20–25 | 57 | 29 | 50.9 | 29 | 2 | 6.9 | ||

| Subtotal (gender) | 94 | 53 | 56.4 | 53 | 4 | 7.5 | ||

| Male | 15–19 | 23 | 7 | 30.4 | 7 | 1 | 14.3 | |

| 20–25 | 63 | 21 | 33.3 | 21 | 2 | 9.5 | ||

| Subtotal (gender) | 86 | 28 | 32.6 | 28 | 3 | 10.7 | ||

| Subtotal (area) | 180 | 81 | 45.0 | 81 | 7 | 8.6 | ||

| Total | Female | 15–19 | 169 | 80 | 47.3 | 79 | 7 | 8.9 |

| 20–25 | 366 | 163 | 44.5 | 162 | 18 | 11.1 | ||

| Subtotal (gender) | 535 | 243 | 45.4 | 241 | 25 | 10.4 | ||

| Male | 15–19 | 44 | 10 | 22.7 | 10 | 1 | 10.0 | |

| 20–25 | 199 | 50 | 25.1 | 48 | 5 | 10.4 | ||

| Subtotal (gender) | 243 | 60 | 24.7 | 58 | 6 | 10.3 | ||

| 778 | 303 | 38.9 | 299 | 31 | 10.4 | |||

Overall, 39% (303/778) of individuals were retested within 6 months of their original chlamydia diagnosis. In the pilot areas 779 positives were eligible for retesting, of whom 303 were retested and 31 were positive. In the context of the South of England where positivity is 7.5%, this equates to over 10 000 tests performed to generate 303 retests.

The results of logistic regression to calculate the OR for retesting are given in table 2, presented as unadjusted and adjusted values; adjusted for area of study, age group (15–19, 20–25) and gender. The outcome was retest between 2 weeks and 6 months (yes/no) of the primary test. In the unadjusted analysis, only female gender was significantly associated with increased odds of retesting (OR 2.54, 95% CI 1.81 to 3.56). In the adjusted analysis, female gender (OR 2.87, 95% CI 2.01 to 4.10) and being tested in Dorset (OR 1.69, 95% CI 1.15 to 2.49) were significantly associated with higher levels of retesting.

Table 2.

Logistic regression of retesting probability, with unadjusted and adjusted ORs (by area of study, gender and age group)

| |

Unadjusted |

Adjusted |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (778) | Retested (243) | Percentage retested | OR | CI |

p Value | OR | CI |

p Value | |||

| Lower 95% | Upper 95% | Lower 95% | Upper 95% | ||||||||

| Area | |||||||||||

| Bristol | 346 | 130 | 38 | Ref | Ref | ||||||

| Cornwall | 252 | 92 | 37 | 0.96 | 0.68 | 1.34 | 0.79 | 0.9 | 0.64 | 1.26 | 0.534 |

| Dorset | 180 | 81 | 45 | 1.36 | 0.94 | 1.96 | 0.1 | 1.69 | 1.15 | 2.49 | 0.008 |

| Gender | |||||||||||

| Male | 243 | 60 | 25 | Ref | Ref | ||||||

| Female | 535 | 243 | 45 | 2.5 | 1.81 | 3.56 | <0.001 | 2.87 | 2.01 | 4.1 | <0.001 |

| Age | |||||||||||

| 15–19 | 213 | 90 | 42 | Ref | Ref | ||||||

| 20–25 | 565 | 213 | 38 | 0.83 | 0.6 | 1.14 | 0.246 | 0.99 | 0.71 | 1.38 | 0.95 |

Among those retested with a confirmed negative or positive result, the positivity of chlamydia was 10.4% (31/299). In logistic regression, there was no significant difference in retest positive by area, age or gender, shown in table 3.

Table 3.

Logistic regression of positivity at retest, with unadjusted and adjusted ORs (by area of study, gender and age group) for those with a confirmed negative or positive result at retest

| |

Unadjusted |

Adjusted |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Retest (299) | Retest positive (31) | Percentage positive | OR | 95% CI |

p Value | OR | 95% CI |

p Value | |||

| Lower | Upper | Lower | Upper | ||||||||

| Area | |||||||||||

| Bristol | 113 | 13 | 11.5 | Ref | |||||||

| Cornwall | 81 | 11 | 13.6 | 1.18 | 0.5 | 2.77 | 0.703 | 1.19 | 0.5 | 2.8 | 0.693 |

| Dorset | 74 | 7 | 9.5 | 0.82 | 0.31 | 2.12 | 0.691 | 0.83 | 0.31 | 2.23 | 0.716 |

| Gender | |||||||||||

| Male | 52 | 6 | 11.5 | Ref | |||||||

| Female | 216 | 25 | 11.6 | 1 | 0.39 | 2.57 | 0.995 | 0.95 | 0.35 | 2.54 | 0.915 |

| Age | |||||||||||

| 15–19 | 81 | 8 | 9.9 | Ref | |||||||

| 20–25 | 187 | 23 | 12.3 | 1.25 | 0.53 | 2.9 | 0.611 | 1.21 | 0.51 | 2.86 | 0.669 |

Postal kit use varied substantially (Dorset 0%, Cornwall 27% and Bristol 85%), and return rates also varied (Cornwall 28/42 (67%), Bristol 98/295 (33%), kits were returned (includes one which had not been sent out by the team)). Bristol offered postal kits as default, Cornwall offered a choice when retesting was offered and Dorset did not offer postal kits, therefore only Cornwall likely reflects patient choice per se.

Additional descriptive analysis of Cornwall experience

Cornwall collected more comprehensive data than the other sites and also undertook more extensive efforts to contact patients for retesting. We had also previously analysed data on reinfection and retesting in Cornwall prior to this study, so were able to re-extract comparable data on retesting prior to the updated guidelines.

In Cornwall, 47.5% (58/122) of those who consented to be recalled, and 26.2% (34/130) of those who did not consent were retested (table 4). Women were more likely to consent than men, but there was no difference by age. In logistic regression, those who consented to be contacted were more than twice as likely to be retested after adjustment for age and gender (OR 2.27, 95% CI 1.32 to 3.91). Conversely those who did consent were less likely to be infected at retest compared with those who did not consent to be contacted (OR 0.16, 95% CI 0.03 to 0.73). Full details are provided in online supplementary table A1.

Table 4.

Number and percentage of individuals in Cornwall retested and reinfected, by consent and contact status

| N | Number contacted | Percentage contacted | Retested | Percentage retested | Cumulative per cent retested | Retested positive | Percentage positive | Retested and contacted | Percentage contacted and retested | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No consent | 130 | NA | NA | 34 | 26 | 26 | 8 | 23.5 | – | – |

| 0 | 19 | 0 | 0 | 19 | 100 | 16 | 2 | 10.5 | 0 | – |

| 1 | 58 | 49 | 84 | 28 | 48 | 39 | 1 | 3.6 | 20 | 41 |

| 2 | 5 | 3 | 60 | 4 | 80 | 42 | 0 | 0.0 | 3 | 100 |

| 3 | 9 | 7 | 78 | 1 | 11 | 43 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 14 |

| 4 | 55 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 44 | 0 | 0.0 | 2 | 100 |

| 5 | 10 | 3 | 30 | 2 | 20 | 46 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 33 |

| 6 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 46 | 0 | – | 0 | – |

| 7 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 20 | 47 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | – |

| 8 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 13 | 48 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | – |

| Total (consent) | 122 | 64 | 52 | 58 | 48 | 3 | 5.2 | 27 | 42 |

*All retests had a confirmed positive or negative result.

Up to eight attempts to contact individuals about retesting were made in Cornwall, but multiple contact attempts (more than 3) did not result in higher retest rates. If patients were not contacted in three attempts, they were unlikely to be contacted at all: only 5/81 patients who were contacted more than three times were successfully contacted.

We reanalysed data collected previously in Cornwall to calculate a comparable retest rate before the pilot was implemented, that is, in the absence of a specific recommendation to retest within 6 months. In Cornwall, there were 9489 individuals tested between January and June 2008, of whom 613 (6.46%) were positive. The results of the subsequent tests according to the result of the first test are given in table 2. Overall, 12.6% (77/613) of those positive were retested in the interval on or after 2 weeks and less than 6 months after the initial test. For individuals who were positive at the initial test and who were retested, 9.1% (7/77) were positive again at the subsequent test (tables 4 and 5).

Table 5.

Retesting prior to implementation of routine retest recommendation in Cornwall7

| Test 1 | Negative (n=8876) | Positive (n=613) | Total (n=9489) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number retested | Test 2 negative | 638 | 70 | 708 |

| Test 2 positive | 36 (5.3%) | 7 (9.1%) | 43 (5.7%) | |

| Total | 674 | 77 | 751 | |

| Proportion retested | 674/8876 (7.6%) | 77/613 (12.6%) | 751/9489 (7.9%) |

Reanalysis of previously published data from Cornwall on reinfection and retesting in 2008–2009.

Discussion

Over a third (39%) of chlamydia-positive individuals were retested following the introduction of three different retesting pilots. Women were more than twice as likely as men to be retested and Dorset achieved higher retest rates than other areas (significant only in the adjusted logistic regression; Bristol (38%), Cornwall (37%), Dorset (45%)). These rates were obtained in the context of normal clinical practice rather than a randomised control trial, and therefore we suggest that retesting rates of 40% are achievable in most areas.

The chlamydia positivity among those retested was 10.4%, which is higher than the overall positivity rate for the south of England in 2012 (7.5%).1 Individuals found to be positive at retest may benefit from additional health promotion and assistance with partner notification. Compared with the previous Cornwall study, the proportion reinfected at retest was similar (10.2% in 2012/13 compared with 9.1% found in our reanalysis of data from 2008).7 The proportion retested with an active recall approach (39%, 304/779) was much higher in the pilot areas than in Cornwall (13%, 77/613) when there was no specific guideline to retest.

In Cornwall, considerable effort was invested in both obtaining consent and contacting clients, but this did not significantly increase the retesting rate in comparison to the Bristol and Dorset pilots. Multiple contacts are therefore unlikely to be a cost-effective use of resources. Similarly, postal kits were preferred by some individuals but resulted in high wastage from non-return of kits, particularly in Bristol where these were the primary method of retesting. Notably, a quarter of those who did not consent to be reminded were retested in Cornwall, and were more likely to be infected than those who had consented to be contacted. This may indicate that individuals are able to accurately assess their risk and seek chlamydia screening actively and appropriately. However, of those who received the intervention (reminders and postal kits), the retesting rates increased to 48%, suggesting that for many people additional strategies are needed.

In this evaluation, retesting rates were fairly high across the three areas compared with rates found in studies conducted in the USA and Australia.8 9 Moderate levels of chlamydia retesting have been reported in England, in the absence of a specific recommendation.10 A systematic review found that reminders and postal screening kits could increase retesting rates by 80% and 25%, respectively.11 Recently Desai et al6 also found that home sampling and SMS reminders appeared to increase retesting, but the range was wide and the evidence limited by study heterogeneity. Studies in Australia indicated that SMS reminders increased retesting rates and that an additional financial incentive did not increase rates further.9

The study is limited because the interventions were not standardised and there was no control group. There was variability in the time frame and approach to offering retesting across the areas. Bristol predominantly offered a postal test at 12 weeks, Dorset arranged a clinic appointment at 12 weeks and Cornwall offered retest by post or clinic appointment at 5 months (20 weeks). Reporting also lacked robustness as individuals could have retested elsewhere (eg, through pharmacy or online testing). No information was available on sexual behaviour since first positive or on partner management of individuals retested. The use of postal kits was highly variable, either offered as default (Bristol), an option (Cornwall) or not offered (Dorset). Return rates of kits were somewhat higher when they had been chosen by patients in Cornwall than offered routinely in Bristol. We removed post code information to preserve anonymity, but these data may be useful in assessing whether distance from clinic predicts preference for postal testing. The findings may not be directly applicable to other settings, since all areas organise chlamydia screening activities differently. However, we believe the similarities in retesting and positivity at retest, despite differences and inconsistencies in implementation through the study, outweigh the differences and indicate that 40% retest rate is a reasonable level to achieve in practice, alongside continued recommendation to test annually and on change of partner.

The change in guidelines was implemented locally to fit with local screening arrangements which is both a strength in that it provides ‘real-life’ insight, but also a weakness since the areas did not all implement retesting in exactly the same way. Other areas in England can learn from our experiences and ensure that current levels of retesting are audited, and that a robust protocol for undertaking and evaluating retesting is implemented prior to local changes in practice. Chlamydia retesting programmes appear feasible within the context of current programmes to identify individuals at continued risk of infection with relatively low resource and time input.

Implications for local practice

Based on the findings and experience from our colleagues providing chlamydia retesting within the NCSP, we recommend that clinics ensure that robust data systems should be in place to enable auditing of retest. Clinics should offer patient choice for retesting method, use automated SMS messaging where possible, consider generating clinic appointments (with SMS reminders a few days in advance). No more than three attempts to contact an individual should be made.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the NIHR Health Protection Research Unit (HPRU) in Evaluation of Interventions for support for this study. They would also like to thank the SW Sexual Health Board and the SHIPP Health Integration Team for support and helpful feedback on the evaluations. KJL received funding from HPRU and Sexual Health 24 during the course of this study. Many thanks to Alison Wilson, PHE Dorset (initiated retesting pilot schemes). Pam Gates, Cornwall—provided data from previous Cornwall project which was reanalysed for this paper.

Footnotes

Twitter: Follow Katy Turner at @katymeturner

Contributors: GA collated data set and liaised with service lead for each programme to describe pilot methodology; did data analysis and interpretation of results; wrote first draft and redraft following review by co-authors. KMET supervised GA and conceived study in conjunction with PJH and NO; contributed to design, analysis, interpretation of data and revision of manuscript. PJH conceived study in conjunction with KMET and NO; involved in design, interpretation and revision of manuscript. JM read and approved paper and provided oversight from the Sexual Health Improvement Programme (SHIPP). NO supervised GA and conceived study in conjunction with KMET and PJH; involved in design, interpretation and revision of manuscript; provided oversight of NCSP activities within study areas. MS provided data from Cornwall, and assisted in data collation and interpretation. KP provided data from Bristol and assisted in data collation and interpretation. CP provided data from Dorset and assisted in data collation and interpretation. KJL assisted in the data analysis and interpretation, and commented on the manuscript drafts. All authors reviewed and commented on drafts of the manuscript and have read and approved the submitted paper.

Funding: KMET was funded by NIHR PDF award (NIHR-PDF-2009-02055). KJL received support from the NIHR HPRU Evaluation of Interventions (Bristol).

Competing interests: ISJME COI forms will be provided separately for relevant authors (KMET/PJH). KMET and PJH were members of the NCSP working group on retesting (meeting December 2012).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: The authors had full access to the data informing this study. All individual level study data are provided as a pdf file as online supplementary material (Supplementary_individual_level_data.pdf). This can be provided as .txt or .xls on request.

References

- 1.England, P.H. NCSP professional site: resources and guidelines (cited 2015). http://www.chlamydiascreening.nhs.uk/ps/resources.asp

- 2.England, P.H. CTAD data table 2013. http://www.chlamydiascreening.nhs.uk/ps/data.asp

- 3.Team, N.C.S.P. Consultation report: routine offer of retest to young adults screening positive for chlamydia 2013.

- 4.Hosenfeld CB, Workowski KA, Berman S et al. Repeat infection with Chlamydia and gonorrhea among females: a systematic review of the literature. Sex Transm Dis 2009;36:478–89. 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3181a2a933 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Haggerty CL, Gottlieb SL, Taylor BD et al. Risk of sequelae after Chlamydia trachomatis genital infection in women. J Infect Dis 2010;201(Suppl 2):S134–55. 10.1086/652395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Desai M, Woodhall SC, Nardone A et al. Active recall to increase HIV and STI testing: a systematic review. Sex Transm Infect 2015;91:314–23. 10.1136/sextrans-2014-051930 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Turner KM, Horner PJ, Trela-Larsen L et al. Chlamydia screening, retesting and repeat diagnoses in Cornwall, UK 2003–2009. Sex Transm Infect 2013;89:70–5. 10.1136/sextrans-2012-050696 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hoover KW, Tao G, Nye MB et al. Suboptimal adherence to repeat testing recommendations for men and women with positive Chlamydia tests in the United States, 2008–2010. Clin Infect Dis 2013;56:51–7. 10.1093/cid/cis771 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guy R, Wand H, Knight V et al. SMS reminders improve re-screening in women and heterosexual men with chlamydia infection at Sydney Sexual Health Centre: a before-and-after study. Sex Transm Infect 2013;89:11–15. 10.1136/sextrans-2011-050370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Woodhall SC, Atkins JL, Soldan K et al. Repeat genital Chlamydia trachomatis testing rates in young adults in England, 2010. Sex Transm Infect 2013;89:51–6. 10.1136/sextrans-2012-050490 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guy R, Hocking J, Low N et al. Interventions to increase rescreening for repeat chlamydial infection. Sex Transm Dis 2012;39:136–46. 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e31823ed4ec [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]