Abstract

Objective

To validate the In-hospital Mortality for PulmonAry embolism using Claims daTa (IMPACT) prediction rule, in a database consisting only of inpatient claims.

Design

Retrospective claims database analysis.

Setting

The 2012 Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project National Inpatient Sample.

Participants

Pulmonary embolism (PE) admissions were identified by an International Classification of Diseases, ninth edition (ICD-9) code either in the primary position or secondary position when accompanied by a primary code for a PE complication. The multivariable IMPACT rule, which includes age and 11 comorbidities, was used to estimate patients’ probability of in-hospital mortality and classify them as low or higher risk (≤1.5% deemed low risk).

Primary and secondary outcome measures

The rule's sensitivity, specificity, positive and negative predictive values (PPV and NPV) and area under the receiver operating characteristic curve statistic for predicting in-hospital mortality with accompanying 95% CIs.

Results

A total of 34 108 admissions for PE were included, with a 3.4% in-hospital case-fatality rate. IMPACT classified 11 025 (32.3%) patients as low risk, and low risk patients had lower in-hospital mortality (OR, 0.17, 95% CI 0.13 to 0.21), shorter length of stay (−1.2 days, p<0.001) and lower total treatment costs (−$3074, p<0.001) than patients classified as higher risk. IMPACT had a sensitivity of 92.4%, 95% CI 90.7 to 93.8 and specificity of 33.2%, 95% CI 32.7 to 33.7 for classifying mortality risk. It had a high NPV (>99%), low PPV (4.6%) and an AUC of 0.74, 95% CI 0.73 to 0.76.

Conclusions

The IMPACT rule appeared valid when used in this all payer, inpatient only administrative claims database. Its high sensitivity and NPV suggest the probability of in-hospital death in those classified as low risk by IMPACT was minimal.

Keywords: GENERAL MEDICINE (see Internal Medicine), INTERNAL MEDICINE, THORACIC MEDICINE, VASCULAR MEDICINE

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Many of the 11 comorbidities of the In-hospital Mortality for PulmonAry embolism using Claims daTa (IMPACT) rule were coded for within the claims data using the validated Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality 29-comorbidity software/schema.

Owing to the lack of out-of-hospital mortality data in the National Inpatient Sample (NIS), we could not evaluate the longer term (30-day) mortality of these patients.

As with all claims databases, the NIS may contain inaccuracies or omissions in coded diagnoses/procedures, leading to the potential for misclassification bias.

The 1.5% cut-point for defining low risk for in-hospital mortality can be considered arbitrary, but was chosen (in the original derivation study) on the basis of a review of area under the receiver operating characteristic curve analysis and previous clinical prediction rules.

The incidence of pulmonary embolism (PE) in the USA has increased substantially over the past decade, with incidence estimates surpassing 112 PEs per 100 000 Americans.1 This increased PE incidence has been attributed to improved diagnostic modalities and is associated with a decreased overall case fatality rate. Some have used these data to suggest that there is a substantial fraction of patients with PE who could potentially be discharged directly from the emergency department, observational unit or hospital following an abbreviated stay.1–3 However, to do so would require a method for estimating the risk of complications in patients with PE, in particular early mortality.

Numerous clinical prediction rules for prospectively estimating short-term mortality of patients with PE have been developed.4 The PE Severity Index (PESI),5 simplified PESI (sPESI)6 and Hestia7 scores are among the most sensitive for classifying early mortality risk, and suggest that at least one-third of all patients with PE could be treated at home or following an abbreviated admission.4 A common theme of these prediction rules is their use of vital signs and laboratory values in addition to comorbidity status.4 For this reason, these rules cannot be implemented in most administrative claims databases. In the current era of cost-conscious healthcare, there is a growing need for a benchmarking rule that payers and hospitals can use to assess whether they are providing optimal and efficient acute care for patients presenting with PE.

Coleman et al8 derived such a multivariable benchmarking rule for in-hospital PE mortality using a large US commercial claims database. This prediction rule, dubbed the In-hospital Mortality for PulmonAry embolism using Claims daTa (IMPACT), consists of 11 comorbidities identified using inpatient or outpatient claims data during the 12 months prior to the index PE event (plus age as a continuous variable) and was demonstrated to have a sensitivity and specificity similar to PESI and sPESI.4 However, since there are many hospital specific and commercial claims databases which contain only data from inpatient admissions,9 they contain insufficient claims data to identify relevant comorbidities to populate the aforementioned rule.

The aim of this study was to determine whether the validity of the IMPACT prediction rule developed in a commercial claims database remained acceptable when utilised in an inpatient only claims database.

Methods

We utilised the 2012 Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project National Inpatient Sample (NIS) for this study.10 The NIS contains data on hospital inpatient stays and covers all patients, including those with Medicare, Medicaid, private insurance and the uninsured. The 2012 inpatient core file contained data on 7 296 968 hospitalisations occurring between 1 January 2012 and 31 December 2012 and was drawn from 4378 hospitals within 44 states. Since only analysis on de-identified data was performed, our study was exempt from institutional review board oversight.

Patients ≥18 years of age with a diagnosis of PE were identified using the International Classification of Diseases, ninth edition, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) codes indicating PE as the primary diagnosis (415.11, 415.12, 415.13 and 415.19). To allow for the inclusion of seriously ill patients with PE, we also included admissions with a secondary diagnosis code for PE and a primary code representing one of the following common complications/treatments of PE: respiratory failure (518.81), cardiogenic shock (785.51), cardiac arrest (427.5), secondary pulmonary hypertension (416.8), syncope (780.2), thrombolysis (99.10) and intubation/mechanical ventilation (96.04, 96.05, 96.70–96.72). Admissions with only a secondary diagnosis of PE and those transferred from another healthcare facility were excluded.

The IMPACT prediction rule (a claims-based in-hospital mortality logistic regression prediction rule initially derived in a large US MarketScan commercial and Medicare claims database) was then evaluated in an all-payer inpatient claims only database:8 1/(1+exp(−x); where ×=−5.833+(0.026×age)+(0.402×myocardial infarction, MI)+(0.368×chronic lung disease)+(0.464×stroke)+(0.638×prior major bleeding)+(0.298×atrial fibrillation)+(1.061×cognitive impairment)+(0.554×heart failure)+(0.364×renal failure)+(0.484×liver disease)+(0.523×coagulopathy)+ (1.068×cancer). The 11 comorbidities in the above equation, which were originally calculated using inpatient and outpatient claims data occurring anytime within 12 months before an index PE event, were calculated only on the basis of the maximum of 25 ICD-9-CM diagnosis codes and procedural codes reported for each discharge in the NIS. When possible, the presence or absence of comorbidities as determined using AHRQ's 29-comorbidity index coding software.10 11 A key aspect of the AHRQ 29-comorbidity coding is the use of a diagnosis-related group (DRG) screen in addition to the traditional ICD-9-CM coding. This DRG screen allows comorbidities to be considered as coexisting medical conditions not directly related to the principal diagnosis or the main reason for admission (likely existing prior to the index hospital stay). Since the comorbidities of prior major bleeding, cognitive dysfunction, stroke, MI and atrial fibrillation are not part of the AHRQ 29-comorbidity schema, we coded these variables using ICD-9-CM diagnosis and procedural codes and implemented a similar DRG screen methodology (see online supplementary appendix 1).

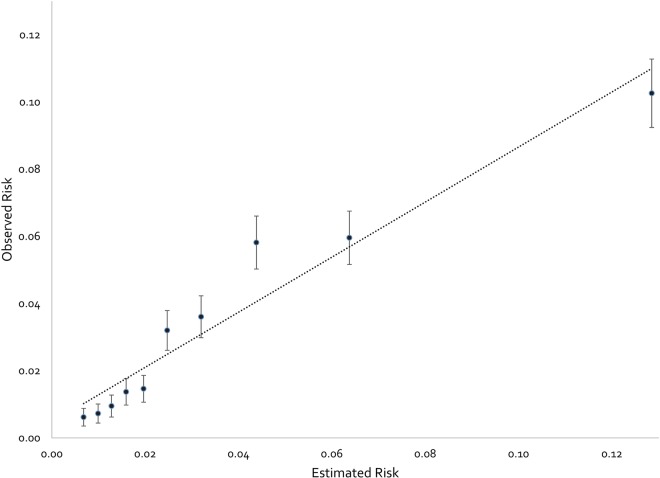

We performed a calibration analysis11 by plotting observed outcome (in-hospital mortality) by decile of predictions by the IMPACT multivariable prediction rule. The calibration plot was characterised by an intercept, which indicates the extent to which predictions are systematically too low or high (‘calibration-in-large’) (a value=0 is ideal), and a calibration slope, which would be equal to 1.0 in the case of a perfect model.

Patients were classified as being low risk for in-hospital mortality if their predicted in-hospital mortality risk using the above equation was ≤1.5% (a threshold defined in the original derivation study on the basis of the area under the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve (AUC) analysis and a review of prior clinical PE in-hospital mortality rules).4 8 To quantify the accuracy of IMPACT for predicting in-hospital mortality in patients with low risk and higher risk PE, we calculated sensitivity (the percentage of patients at high risk for in-hospital mortality who are correctly identified as being high risk as evidenced by in-hospital death occurring), specificity (the percentage of patients at low risk of in-hospital mortality who are correctly identified as being low risk as evidenced by survival to discharge), positive predictive value (PPV; the probability that in the case of being classified as high risk for in-hospital mortality, the patient dies prior to discharge) and negative predictive value (NPV; the probability that in the case of being classified as low risk for in-hospital death, the patient survives to discharge) along with 95% CIs. The AUC was calculated to assess the rule's discriminative power to correctly predict inpatient mortality.

We defined an abbreviated hospital stay as ≤1, ≤2 or ≤3 days based on values utilised in previous studies,12 and determined the proportion of patients in this category. In order to estimate the potential cost savings from an early discharge, we calculated the difference in total hospital costs between low-risk patients having and not having an abbreviated hospital stay. Total hospital costs were estimated from total hospital charges reported in the NIS using supplied cost-to-charge ratios.10

All data management and statistical analyses were performed using SAS V.9.2 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, North Carolina, USA) or IBM SPSS Statistics V.22.0 (IBM Corp, Armonk, New York, USA). Categorical comparisons were made using Pearson's χ2 tests and continuous comparisons were made using either independent samples t tests or Mann-Whitney U tests (where appropriate). A p value <0.05 was considered statistically significant in all situations. The preparation of this report was in accordance with the Transparent Reporting of a multivariable prediction model for Individual Prognosis Or Diagnosis (TRIPOD).13

Results

A total of 34 108 PE admissions were included in this analysis; 97.7% had a primary ICD-9-CM code for PE. Characteristics of patients at baseline are reported in table 1.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics for low-risk and higher-risk patients

| Total, N (%) N=34 108 |

Low risk, N (%) N=11 025 |

Higher risk, N (%) N=23 083 |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years, mean±SD) | 61.93±17.16 | 44.21±11.52 | 70.40±12.24 |

| Male gender | 15 953 (46.7) | 5400 (49.0) | 10 553 (45.7) |

| Living in a rural area | 2318 (6.8) | 623 (5.7) | 1695 (7.3) |

| Payer | |||

| Medicare | 17 227 (50.6) | 1143 (10.4) | 16 084 (69.8) |

| Medicaid | 3193 (9.4) | 1823 (16.6) | 1370 (5.9) |

| Private insurance | 10 606 (31.2) | 6058 (55.1) | 4548 (19.7) |

| Self-pay | 1733 (5.1) | 1190 (10.8) | 543 (2.4) |

| No charge | 169 (0.5) | 123 (1.1) | 46 (0.2) |

| Other | 1109 (3.4) | 656 (6.0) | 453 (2.0) |

| Comorbid diseases, included in claims-based rule | |||

| Myocardial infarction | 572 (1.7) | 26 (0.2) | 546 (2.4) |

| Chronic lung disease | 8530 (25.0) | 1093 (9.9) | 7437 (32.2) |

| Cerebrovascular disease (stroke) | 201 (0.6) | 9 (0.08) | 192 (0.8) |

| Prior major bleeding | 1167 (3.4) | 46 (0.4) | 1121 (4.8) |

| Atrial fibrillation | 3684 (10.8) | 88 (0.08) | 3596 (1.6) |

| Cognitive impairment (dysfunction) | 2362 (6.9) | 1 (0.01) | 2361 (10.2) |

| Heart failure | 4316 (12.7) | 105 (9.5) | 4211 (18.2) |

| Renal failure | 3420 (10.0) | 162 (1.5) | 3258 (14.1) |

| Liver disease (dysfunction) | 774 (2.3) | 70 (0.6) | 704 (3.0) |

| Coagulopathy | 2213 (6.5) | 172 (1.6) | 2041 (8.8) |

| Cancer | 5035 (14.8) | 4 (0.04) | 5031 (21.8) |

| Comorbid diseases; AHRQ-29 comorbidity measure | |||

| AIDS | 90 (0.3) | 50 (0.5) | 40 (0.2) |

| Alcohol abuse | 1079 (3.2) | 425 (3.9) | 654 (2.8) |

| Deficiency anaemias | 6653 (19.5) | 1539 (14.0) | 5114 (22.2) |

| Rheumatoid arthritis/collagen vascular diseases | 1257 (3.7) | 352 (3.2) | 905 (3.9) |

| Chronic blood loss anaemia | 357 (1.0) | 121 (1.1) | 236 (1.0) |

| Depression | 4303 (12.6) | 1446 (13.1) | 2857 (12.4) |

| Diabetes, uncomplicated | 6421 (18.8) | 1326 (12.0) | 5095 (22.1) |

| Diabetes with chronic complications | 983 (2.9) | 178 (1.6) | 805 (3.5) |

| Drug abuse | 906 (2.7) | 536 (4.9) | 370 (1.6) |

| Hypertension | 19 655 (57.6) | 4140 (37.6) | 15 515 (67.2) |

| Hypothyroidism | 4438 (13.0) | 883 (8.0) | 3555 (15.4) |

| Lymphoma | 481 (1.4) | 0 (0) | 481 (2.1) |

| Fluid and electrolyte disorders | 7132 (20.9) | 1466 (13.3) | 5666 (24.5) |

| Metastatic cancer | 2622 (7.7) | 3 (0.03) | 2619 (11.3) |

| Other neurological disorders | 2769 (8.1) | 534 (4.8) | 2235 (9.7) |

| Obesity | 6732 (19.7) | 2823 (25.6) | 3909 (16.9) |

| Paralysis | 640 (1.9) | 161 (1.5) | 479 (2.1) |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 1722 (5.0) | 155 (1.4) | 1567 (6.8) |

| Psychoses | 1580 (4.6) | 719 (6.5) | 861 (3.7) |

| Pulmonary circulation disorders | 4064 (11.9) | 867 (7.9) | 3197 (13.9) |

| Solid tumour without metastasis | 1977 (5.9) | 1 (0.01) | 1976 (8.6) |

| Peptic ulcer disease excluding bleeding | 9 (0.03) | 4 (0.04) | 5 (0.02) |

| Valvular disease | 1983 (5.8) | 281 (2.5) | 1702 (7.4) |

| Weight loss | 1559 (4.6) | 157 (1.4) | 1402 (6.1) |

AHRQ, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

The overall in-hospital PE case-fatality rate was 3.4%. Our calibration analysis demonstrated increasing observed in-hospital mortality risk across the progressively increasing deciles of IMPACT predicted risk, a slope of 0.82 and an intercept of 0.0046 (figure 1). The IMPACT prediction rule classified 11 025 (32.3%) patient admissions as low risk, and low-risk patients had lower in-hospital mortality (odds reduction of 83%; OR, 0.17, 95% CI 0.13 to 0.21), shorter length of stay (LOS) (−1.2 days, p<0.001) and lower total treatment costs (−$3074, p<0.001) than patients classified as higher risk (table 2). Of low-risk patients, 13.1%, 31.1% and 47.7% were discharged within 1, 2 and 3 days of admission. Low-risk patients discharged within 1 day accrued $5465, 95% CI $5018 to $5911 less in treatment costs than those staying longer. Discharge within 2 or 3 days in low-risk patients was also associated with a reduced cost of hospital treatment ($5820, 95% CI $5506 to $6133 and $6314, 95% CI $6031 to $6597, respectively) when compared to those staying longer.

Figure 1.

Calibration plot depicting observed in-hospital mortality by deciles of In-hospital Mortality for PulmonAry embolism using Claims daTa estimated in-hospital mortality risk. Error bars represent 95% CIs. The linear relationship depicted by the dotted line is defined by an equation for a straight line with a calibration slope of 0.82 and (calibration slope) an intercept of 0.0046 (‘calibration-in-the-large’).

Table 2.

Comparison of outcomes between patients classified as low risk and higher risk by the IMPACT prediction rule

| Total, N (%) N=34 108 |

Low risk, N (%) N=11 025 |

Higher risk, N (%) N=23 083 |

p Value* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| In-hospital mortality | 1158 (3.4) | 88 (0.8) | 1070 (4.6) | <0.001 |

| Total treatment cost (mean±SD) | $10 976±$12 240 | $8899±$8344 | $11 972±$13 610 | <0.001 |

| Length of stay (days, mean±SD, %) | 5.2±4.5 | 4.3±3.3 | 5.6±4.9 | <0.001 |

| Within 1 day† | 3160 (9.6) | 1430 (13.1) | 1730 (7.9) | <0.001 |

| Within 2 days† | 7791 (23.6) | 3397 (31.1) | 4394 (20.0) | <0.001 |

| Within 3 days† | 12 715 (38.6) | 5215 (47.7) | 7500 (34.1) | <0.001 |

*p Value for the comparison between low risk and higher risk groups.

†Calculated only when surviving to discharge.

IMPACT, In-hospital Mortality for PulmonAry embolism using Claims daTa.

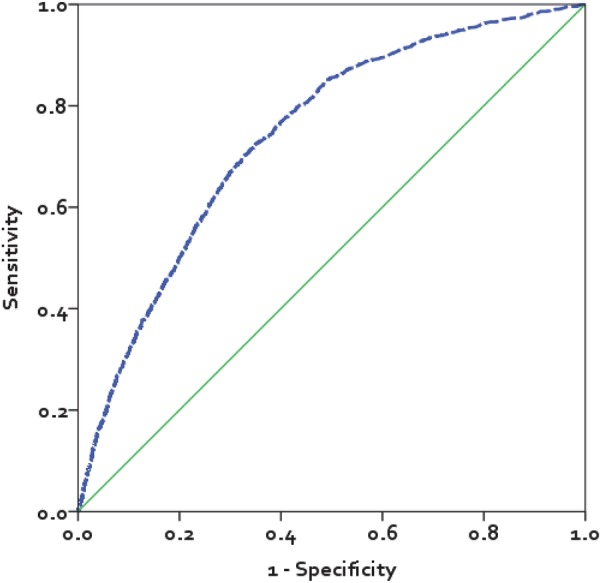

The sensitivity and specificity of IMPACT for prognosticating in-hospital mortality was 92.4%, 95% CI 90.7 to 93.8 and 33.2%, 95% CI 32.7 to 33.7, respectively (table 3). IMPACT's high NPV (>99%) suggests that the probability of in-hospital death in those whom it classifies as low risk is low, but its low PPV (4.6) suggests that it will classify patients who will survive to discharge as high risk (anticipated to die in-hospital). The AUC of IMPACT was 0.74, 95% CI 0.73 to 0.76 (figure 2).

Table 3.

Test characteristics for the IMPACT rule for predicting in-hospital mortality

| Test characteristic | Estimate (95% CI) |

|---|---|

| Sensitivity, % | 92.4 (90.7 to 93.8) |

| Specificity, % | 33.2 (32.7 to 33.7) |

| PPV, % | 4.6 (4.4 to 4.9) |

| NPV, % | 99.2 (99.0 to 99.4) |

| AUC | 0.74 (0.73 to 0.76) |

AUC, area under the receiver operator characteristic curve; IMPACT, In-hospital Mortality for PulmonAry embolism using Claims daTa; NPV, negative predictive value; PPV, positive predictive value.

Figure 2.

Receiver operating characteristic curve for the In-hospital Mortality for PulmonAry embolism using Claims daTa (IMPACT) prediction rule. The area under the curve for IMPACT was 0.74, 95% CI 0.73 to 0.76.

Discussion

The IMPACT prediction rule originally developed by Coleman et al8 in a large US commercial claims database remained valid when adapted for use in the NIS all payer, inpatient only claims database. This rule classified in-hospital mortality risk with high sensitivity (and a high NPV) but modest specificity, meaning it classified nearly all patients who died during the index PE admission into the higher risk group, but also classified patients who survived to discharge as high risk (also supported by the small PPV indicating that many of the patients classified as high risk were false positives). While any prediction rules would ideally be 100% sensitive and specific, high sensitivity is preferable to high specificity when making the decision to discharge a patient with PE early from the hospital or treat them on an outpatient basis. Moreover, the observed sensitivity, specificity and proportion of patients deemed to be at low risk for early mortality when using the IMPACT prediction rule was on par with that seen with the PESI, sPESI and Hestia rules.4 Despite IMPACT having similar prognostic accuracy to previously developed clinical rules, we strongly suggest that the claims-based rule not be used to make treatment decisions, as it was not developed in a clinical setting. The true value of the IMPACT rule is as a benchmarking tool for payers and hospitals to quickly and inexpensively benchmark population rates of PE treated at home or following an abbreviated hospital admission; as well as, to assure high-risk patients remain in-hospital for an adequate period of time.

The IMPACT benchmarking rule has significant potential value due to the common and expensive nature of treating PE in hospital. There are approximately 181 000 admissions for PE yearly in the USA, with a mean LOS of >5 days and hospital treatment costs >$10 000/admission.1 10 Importantly, our analysis found that only 13.1% of patients classified as low risk for in-hospital death were discharged within 1 day of admission, 31.1% within 2 days and <50% were discharged within 3 days. Even though IMPACT was not 100% accurate, and there are valid reasons why clinicians might not discharge a patient with PE early (eg, need for adequate home circumstances and medication adherent patients2 3), when compared to recent studies performed in Canada where approximately 50% of patients with PE were treated as outpatients;14–16 our data suggest that many patients with PE treated at US hospitals may be kept in-house longer than is medically necessary. Since data from this study suggest that a low-risk patient discharged within 3 days has less than half the hospital costs compared to a low-risk patient staying >3 days, we believe there are significant cost savings opportunities to institutions and the healthcare system by assuring patients with PE are safely discharged as soon as possible.

A strength of the IMPACT rule, and subsequently our analysis, was our use of the validated AHRQ 29-comorbidity software/Elixhauser coding schema whenever possible.10 11 This ICD-9-CM coding schema for comorbidities has been demonstrated to be the best predictor of in-hospital mortality among common comorbidity indices for administrative data.17 The AHRQ 29-comorbidity software itself codes for 29 comorbidities; of which 8 comorbidities were included in IMPACT. A key aspect of AHRQ-29 coding is the use of a DRG screen so that comorbidities can be considered as coexisting medical conditions not directly related to the principal diagnosis or the main reason for admission and thus most likely existing prior to the index hospital stay.

Our analysis has some limitations. First, owing to the unavailability of out-of-hospital mortality data in the NIS, we could not evaluate 30-day mortality like some previous clinical rules/scores.4 However, most commercial claims databases and hospitals will also not have broad access to out-of-hospital mortality status. It has been long appreciated that the highest risk of complications or death due to PE is in the first few hours to a week after diagnosis.18–21 Despite the fact that the in-hospital mortality rate observed in this study (3.4%) is lower than the 30-day mortality rate (approximately 9%) reported in studies of clinical prediction rules such as PESI,5 6 the sensitivity of clinical prediction rules do not vary markedly when used to predict in hospital or 30-day mortality.5 22 23 For these reasons, in-hospital mortality seems a reasonable end point for assessing whether a patient is a good candidate for early discharge (or outpatient treatment). Second, as with all claims databases, the NIS may contain inaccuracies or omissions in coded diagnoses/procedures, leading to the potential for misclassification bias. Finally, the use of 1.5% as a cut-point for low risk was somewhat arbitrary. The 1.5% value was chosen on the basis of a review of the ROC curve (to roughly identify a value balancing sensitivity and specificity) and because it approximates the in-hospital mortality rate seen in patients with PE at very low risk and low risk (classes I and II) in the original PESI derivation study.5 8

Conclusion

The IMPACT prediction rule appeared valid when adapted for use in this all payer, inpatient only administrative claims database. The rule classified patients’ mortality risk with high sensitivity, and consequently may be valuable to those wishing to benchmark rates of PE treated at home or following an abbreviated hospital admission.

Footnotes

Contributors: CGK, CIC, CC, JRS and WFP participated in study concept and design and analysis and interpretation of data. CIC, CC, JRS were responsible for acquisition of data. CKG, CIC, WFP were involved in drafting of the manuscript. CIC, CC, JRS and WFP were responsible for critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. CIC, CC and JRS were responsible for administrative, technical or material support. CIC, CGK and CIC were responsible for study supervision and had full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. All the authors read and approved the final manuscript. The authors meet the criteria for authorship as recommended by the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICJME) and were fully responsible for all content and editorial decisions they were also involved in all stages of manuscript development.

Funding: This work was supported by Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC, Raritan, NJ (no grant number).

Competing interests: CIC has received grant funding and consultancy fees from Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC, Raritan, New Jersey, USA; Bayer Pharma AG, Berlin, Germany; and Boehringer-Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals, Inc, Ridgefield, Connecticut, USA. CC and JRS are employees of Janssen Scientific Affairs LLC, Raritan, New Jersey, USA. WFP has received grant funding and consultancy fees from Abbott, Alere, Banyan, Cardiorentis, Janssen, Portola, Roche and The Medicine’s Company, Prevencio and Singulex.

Ethics approval: The ethical approval is obtained from AHRQ.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: The 2012 NIS data utilised for this study can be obtained directly from AHRQ.

References

- 1.Wiener RS, Schwartz LM, Woloshin S. Time trends in pulmonary embolism in the United States: evidence of overdiagnosis. Arch Intern Med 2011;171:831–7. 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kearon C, Akl EA, Comerota AJ, et al. , American College of Chest Physicians. Antithrombotic therapy for VTE disease: Antithrombotic Therapy and Prevention of Thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest 2012;141:e419S–94S. 10.1378/chest.11-2301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Konstantinides SV, Torbicki A, Agnelli G, et al. , Task Force for the Diagnosis and Management of Acute Pulmonary Embolism of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). 2014 ESC guidelines on the diagnosis and management of acute pulmonary embolism. Eur Heart J 2014;35:3033–69. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehu283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kohn CG, Mearns ES, Parker MW et al. . Prognostic Accuracy of clinical prediction rules for early post-pulmonary embolism all-cause mortality: a bivariate meta-analysis. Chest 2015;147:1043–62. 10.1378/chest.14-1888 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aujesky D, Obrosky DS, Stone RA et al. . Derivation and validation of a prognostic model for pulmonary embolism. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2005;172:1041–6. 10.1164/rccm.200506-862OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jiménez D, Aujesky D, Moores L, et al. , IETE Investigators. Simplification of the pulmonary embolism severity index for prognostication in patients with acute symptomatic pulmonary embolism. Arch Intern Med 2010;170:1383–9. 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zondag W, den Exter PL, Crobach MJ, et al. , Hestia Study Investigators. Comparison of two methods for selection of out of hospital treatment in patients with acute pulmonary embolism. Thromb Haemost 2013;109:47–52. 10.1160/TH12-07-0466 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Coleman CI, Kohn CG, Bunz TJ. Derivation and validation of the In-hospital Mortality for Pulmonary embolism using Claims Data (IMPACT) prediction rule. Curr Med Res Opin 201531:1461–8. 10.1185/03007995.2015.1062748 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research. International Digest of Databases. http://www.ispor.org/DigestOfIntDB/CountryList.aspx (last accessed on 8 Apr 2015).

- 10.HCUP National Inpatient Sample (NIS). Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP). Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 2012. http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/nisoverview.jsp (last accessed on 10 Apr 2015). [Google Scholar]

- 11.Steyerberg EW, Vickers AJ, Cook NR et al. . Assessing the performance of prediction models: a framework for traditional and novel measures. Epidemiology 2010;21:128–38. 10.1097/EDE.0b013e3181c30fb2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zondag W, Kooiman J, Klok FA et al. . Outpatient versus inpatient treatment in patients with pulmonary embolism: a meta-analysis. Eur Respir J 2013;42:134–44. 10.1183/09031936.00093712 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moons KG, Altman DG, Reitsma JB et al. . Transparent Reporting of a multivariable prediction model for Individual Prognosis or Diagnosis (TRIPOD): explanation and elaboration. Ann Intern Med 2015;162:W1–73. 10.7326/M14-0698 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Erkens PM, Gandara E, Wells P et al. . Safety of outpatient treatment in acute pulmonary embolism. J Thromb Haemost 2010;8:2412–17. 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2010.04041.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kovacs MJ, Hawel JD, Rekman JF et al. . Ambulatory management of pulmonary embolism: a pragmatic evaluation. J Thromb Haemost 2010;8:2406–11. 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2010.03981.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Baglin T. Fifty per cent of patients with pulmonary embolism can be treated as outpatients. J Thromb Haemost 2010;8:2404–5. 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2010.04055.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sharabiani MT, Aylin P, Bottle A. Systematic review of comorbidity indices for administrative data. Med Care 2012;50:1109–18. 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31825f64d0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gorham LW. A study of pulmonary embolism. II. The mechanism of death; based on a clinicopathological investigation of 100 cases of massive and 285 cases of minor embolism of the pulmonary artery. Arch Intern Med 1961;108:189–207. 10.1001/archinte.1961.03620080021003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dalen JE, Alpert JS. Natural history of pulmonary embolism. Prog Cardiovasc Dis 1975;17:259–70. 10.1016/S0033-0620(75)80017-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Conget F, Otero R, Jiménez D et al. . Short-term clinical outcome after acute symptomatic pulmonary embolism. Thromb Haemost 2008;100:937–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Miniati M, Monti S, Bottai M et al. . Survival and restoration of pulmonary perfusion in a long-term follow-up of patients after acute pulmonary embolism. Medicine (Baltimore) 2006;85: 253–62. 10.1097/01.md.0000236952.87590.c8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vanni S, Nazerian P, Pepe G et al. . Comparison of two prognostic models for acute pulmonary embolism: clinical vs. right ventricular dysfunction guided approach. J Thromb Haemost 2011;9:1916–23. 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2011.04459.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Palmieri V, Gallotta G, Rendina D et al. . Troponin I and right ventricular dysfunction for risk assessment in patients with nonmassive pulmonary embolism in the Emergency Department in combination with clinically based risk score. Intern Emerg Med 2008;3:131–8. 10.1007/s11739-008-0134-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]