Abstract

Background

Psychosocial factors impact survival in patients undergoing cardiac transplantation, but it is unclear whether they affect outcomes in patients undergoing left ventricular assist device (LVAD) implantation as destination therapy (DT).

Methods

Patients undergoing DT LVAD at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota from February 2007 to December 2013 were included. Psychosocial characteristics at the time of LVAD implantation were abstracted from the medical record. Andersen-Gill and Cox models were used to examine the association between psychosocial characteristics and all-cause readmission and death, respectively. Patients were censored at death or last follow-up through September 2014.

Results

Among 136 patients (mean age 64 years, 17% female), most were married/living with a partner (82%), half (55%) had post-high school education, and a history of depression was common (32%). While most patients were former tobacco users (60%) only a small proportion were current tobacco users (10%), had a history of alcohol abuse (16%) or illegal drug use (7%). After a mean follow-up of 2.2 ±1.8 years, 78% of patients had been readmitted (range 0–14 per person) and 49% had died. There were no statistically significant differences in the risk of death according to psychosocial characteristics. However, current tobacco users had lower risk of readmission (adjusted HR 0.57, 95% CI 0.38–0.88), while illegal drug use (HR 1.55, 95% CI 1.01–2.35) and depression (HR 1.77, 95% CI 1.40–2.22) were associated with higher readmission risk.

Conclusions

Psychosocial characteristics are not significant predictors of death, but are associated with readmission risk after DT LVAD.

Keywords: psychosocial, heart failure, left ventricular assist device, depression, mortality

INTRODUCTION

Left ventricular assist devices (LVAD) are increasingly utilized as destination therapy (DT) in patients that are not candidates for heart transplantation1–4. While survival after DT LVAD has improved over time, hospital readmissions and their associated morbidity remain high5. Optimal patient selection is essential in improving outcomes, but many of the factors associated with favorable outcomes remain poorly understood.

Psychosocial characteristics such as depression have been associated with worse outcomes in patients with heart failure6, including in patients undergoing heart transplantation7. However, much less is known about whether psychosocial characteristics predict worse outcomes after DT LVAD. Maltby, et al retrospectively applied the psychosocial assessment of candidates for transplant (PACT) to 48 patients undergoing LVAD at a single center, and found that patients with lower scores had higher 30-day readmission rates8. Cogswell, et al reported increased mortality and risk of driveline infections in 20 patients with active substance abuse compared to those without9. Although prior studies hint towards the importance of understanding psychosocial factors in DT LVAD patients, they are small in number and only assess certain characteristics. A recent systematic review highlighted the paucity of data evaluating the association between psychosocial characteristics and outcomes, and called for additional research10.

It is important for us to better understand the role that psychosocial factors may play in outcomes after DT LVAD. Unlike transplant, where the limited organ supply requires choosing candidates with optimal psychosocial characteristics, DT LVAD therapy is more readily available as it does not rely on organ donors. While the International Society of Heart and Lung Transplantation recommends that all potential LVAD candidates undergo a detailed psychosocial evaluation11, there are no clear guidelines on what constitutes an acceptable psychosocial risk. As a result, many programs will offer DT LVAD to candidates despite psychosocial concerns if it is felt they will otherwise benefit. Data are needed to inform programs about whether such candidates are truly at elevated risk of adverse outcomes.

Our study aims to address these gaps in knowledge by comprehensively examining the association between psychosocial characteristics pre-LVAD with outcomes following implantation.

METHODS

Identification of Patients

All patients undergoing LVAD as DT at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota from 2007 through December 31, 2013 were eligible for inclusion. If patients were initially implanted as DT, but then became eligible for transplant, they were censored at the time of heart transplant. The study was approved by the Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Board. Dr. Dunlay’s time to complete the study was funded through the NIH (K23 HL 116643). The authors are solely responsible for the design and conduct of this study, all study analyses, the drafting and editing of the paper and its final contents.

Psychosocial Characteristics

Psychosocial characteristics assessed include marital status, tobacco, alcohol and illegal drug use, history of depression, education level, and health insurance payer. All patients are seen by a social worker for review of psychosocial factors prior to LVAD. Selected patients are seen by a psychiatrist in consultation if clinically indicated. Marital status and education were defined based on patient self-report in a survey that all Mayo Clinic patients are asked to complete annually as a part of their care. Marital status was categorized as married/living with a partner, single/never married, divorced, or widowed. Education was categorized as less than high school, high school graduate, some college or 2-year degree, 4-year college graduate, or post-graduate studies. Tobacco use was defined by tobacco use in any form (smoking or chewing tobacco) and categorized as never-user, current if currently using or quit <6 months ago, or former tobacco user. Alcohol use was defined as none/minimal if the patient drank no alcohol or only rare/occasional alcohol. Moderate alcohol use was defined as up to 1 drink per day for women or 2 drinks per day for men. Heavy alcohol use was defined as more than 8 drinks a week for women or 15 drinks per week for men or recurrent binge drinking12. Patients were categorized as alcohol abusers if they were self-described alcoholics, previously attended an alcohol treatment program, had prior legal issues due to alcohol, or were felt to abuse alcohol by psychiatric or social worker assessment. Illegal drug use was defined as never user, former non-intravenous drug user, former intravenous drug user, or current non-intravenous drug user if currently using or quit <6 months ago. There were no patients who were current intravenous drug users. Depression was defined by documentation by a physician or social worker of a current or prior diagnosis of major depressive disorder or depression requiring treatment. Adjustment disorder was not included in this definition. Some patients also had the Patient Health Questionnaire 9 (PHQ-9) administered pre-LVAD. As this was only present in a portion of the population, and scores can be elevated in the setting of medical illness for reasons other than depression, we did not include results in our definition of depression. The patient’s primary insurance payer was categorized as either government (Medicare or Medicaid) or private. There were no uninsured patients.

Additional Patient Characteristics

All other patient characteristics were abstracted from data in the electronic medical record. Clinicians’ diagnoses were used to define hypertension and peripheral vascular disease. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) was defined based on clinician’s diagnosis or greater than mild obstructive lung disease on pulmonary function testing. Cerebrovascular disease was defined as a prior history of stroke or transient ischemic attack, prior carotid revascularization, or moderate or greater carotid stenosis on ultrasound pre-LVAD. Diabetes mellitus was defined by physician diagnosis or use of diabetes medications. Body mass index (BMI) (kg/m2) was calculated using height and weight pre-LVAD and obesity included a BMI ≥30 kg/m2. All laboratory data were taken from the morning of LVAD surgery or the closest date prior to that point if not available on that day (all within 1 week pre-LVAD). Echocardiograms were performed and evaluated by the Mayo Clinic Echocardiographic Laboratory using M-mode, quantitative, and semiquantitative methods to measure left ventricular ejection fraction (EF) according to the American Society of Echocardiography guidelines13. The Interagency Registry for Mechanically Assisted Circulatory Support (INTERMACS) patient profile has been used to describe the severity of illness prior to device implantation and ranges in score from 1 (critical cardiogenic shock) to 7 (advanced New York Heart Association class III symptoms)14. The Leitz Miller score (developed to predict in-hospital mortality, although never validated for use in patients with continuous flow LVADs) was calculated using pre-operative variables as: 7 points for platelets ≤148,000/µL, 5 points for albumin ≤3.3 g/dL, 4 points for INR>1.1, 4 points for use of vasodilators, 3 points for mean pulmonary artery pressure <25mm Hg, 2 points for AST>45 U/mL, 2 points for hematocrit ≤34%, 2 points for blood urea nitrogen >51 U/dL, and 2 points for no intravenous inotropes1.

Outcomes

Deaths were as noted in the medical record. For patients who were still alive at last follow-up, they were censored at their date of last follow-up. Readmissions were defined as all-cause hospitalizations at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota that occurred during follow-up through September 30, 2014. The primary cause of readmission was classified by the primary International Classification of Diseases, 9th revision (ICD-9) code and verified by manual record review. The initial postoperative length of stay was defined as the number of days from the time of LVAD implantation to hospital discharge.

Statistical analysis

The association between psychosocial characteristics and mortality were examined using Kaplan Meier curves and differences compared using the log-rank test. Cox proportional hazard regression models were used to assess the association between psychosocial characteristics and death adjusting for potential confounders. Andersen Gill models were used to examine the association between psychosocial characteristics and all-cause readmission. Unlike traditional Cox models, which only account for the first readmission, Andersen Gill models account for the impact of multiple readmissions in generating a hazard ratio. Differences in the proportion of cause-specific readmissions according to psychosocial factors were analyzed using Chi-square and Fisher’s exact test. Analyses were performed using STATA version 10.0. A p value of <0.05 was used as the level of significance.

RESULTS

In total, 136 patients were implanted with LVAD as DT during the study period. The baseline characteristics of the population are shown in Table 1. Most patients were older (mean age 63.6 years), male (83.1%), and had ischemic cardiomyopathy (52.9%). The primary contraindication to transplant was age in 76 (55.9%), obesity (BMI≥35 kg/m2) in 10 (7.4%), other comorbidities in 24 (18.5%), psychosocial factors such as substance abuse, depression, or lack of social support in 17 (12.5%), and other reasons in 7 (5.1%). Most patients had multiple contraindications to transplant. At the time of LVAD implantation, most patients were married/living with a partner (82.4%) and approximately half had some post-high school education. While most patients were former smokers (59.6%), only a small fraction of patients were current smokers (10.3%). Furthermore, while a small proportion of patients had a history of heavy alcohol use (16.3%) or illegal drug use (6.7%), very few were currently heavy alcohol drinkers (n=5) or actively using drugs (n=3). Based upon documentation in the medical record, after LVAD eight patients used tobacco (four current users at the time of LVAD, four former users), three patients used alcohol excessively (two former heavy alcohol users, one with no known history of alcohol abuse), and four patients used illegal drugs (three prior users, one new user).

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of 136 Patients

| Characteristic | Missing (N) | Summary |

|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 0 | 63.6 (11.8) |

| Male, N(%) | 0 | 113 (83.1) |

| Ischemic, N(%) | 0 | 72 (52.9) |

| Prior sternotomy, N(%) | 0 | 73 (53.7) |

| Baseline EF, % | 0 | 17.5 (7.3) |

| Comorbidities | ||

| Depression | 0 | 43 (31.9) |

| Hypertension, N(%) | 0 | 65 (48.1) |

| Diabetes, N(%) | 0 | 51 (37.5) |

| Peripheral vascular disease, N(%) | 0 | 31 (22.8) |

| COPD, N(%) | 0 | 22 (16.2) |

| Cerebrovascular disease, N(%) | 0 | 41 (30.1) |

| Obese, N(%) | 0 | 53 (39.0) |

| Charlson comorbidity index, median (25th–75th percentile) | 0 | 4 (3, 6) |

| Laboratory Data | ||

| Total bilirubin | 1 | 1.4 (1.1) |

| Aspartate aminotransferase | 1 | 68.4 (167.9) |

| Alanine aminotransferase | 2 | 72.0 (202.9) |

| Albumin ≤3.3 mg/dL | 6 | 27 (20.8) |

| Platelets ≤148,000 | 0 | 60 (44.1) |

| Blood urea nitrogen | 0 | 31.9 (15.3) |

| Creatinine >1.5 mg/dL | 0 | 46 (33.8) |

| INR>1.1 | 1 | 99 (73.3) |

| INTERMACS profile | 0 | 3 (2, 4) |

| Leitz-Miller score, median (25th, 75th percentile) | 6 | 10 (6, 13) |

| Marital status | 0 | |

| Married/ living with a partner, N(%) | 112 (82.4) | |

| Single/ never married, N(%) | 9 (6.6) | |

| Divorced, N(%) | 7 (5.1) | |

| Widowed, N(%) | 8 (5.9) | |

| Tobacco use | 0 | |

| Never user | 41 (30.1) | |

| Former tobacco use | 81 (59.6) | |

| Current tobacco use | 14 (10.3) | |

| Alcohol use | 1 | |

| No/ minimal alcohol use, N(%) | 77 (57.0) | |

| Current moderate consumption, N(%) | 36 (26.7) | |

| Former heavy consumption/ abuse, N(%) | 17 (12.6) | |

| Current heavy consumption/ abuse, N(%) | 5 (3.7) | |

| Illegal drug use | 1 | |

| None, N(%) | 126 (93.3) | |

| Former non-intravenous, N(%) | 4 (2.7) | |

| Former intravenous, N(%) | 2 (1.5) | |

| Current non-intravenous, N(%) | 3 (2.2) | |

| Education | 21 | |

| Didn’t graduate high school, N(%) | 10 (8.7) | |

| High school graduate/ GED, N(%) | 42 (36.5) | |

| Some college or 2-year degree, N(%) | 24 (20.9) | |

| 4-year degree, N(%) | 25 (21.7) | |

| Post-graduate studies, N(%) | 14 (12.2) | |

| Distance from Implanting Center (miles) | 2 | |

| <120 | 38 (28.4) | |

| 120–240 | 30 (22.4) | |

| >240 | 66 (49.3) | |

| Primary Insurer | 1 | |

| Medicare or Medicaid (government) | 96 (71.1) | |

| Private | 39 (28.9) |

A history of depression was common (31.9%), and 27 (62.8%) patients with a history of depression were taking anti-depressants at the time of LVAD implantation. In total, 40 (29.4%) patients saw a psychiatrist prior to LVAD implantation. The PHQ-9 was administered in 44 (32.4%) patients pre-LVAD, and scores were indicative of depression severity of none/ minimal (score 0–4), mild (score 5–9), moderate (score 10–14), and moderately severe (score 15–19) in 27.3%, 36.4%, 29.5%, and 6.8%, respectively. While PHQ-9 scores were not significantly different in patients with a history of depression vs. those without (mean 8.5 vs. 7.1, p=0.38), patients with a history of depression more often had scores indicative of at least moderate depression (53.8% vs. 29.0%).

The median (25th–75th percentile) length of stay after LVAD implantation was 17 (11, 28) days. In total, 16 patients did not survive to hospital discharge after their LVAD implantation. There was no difference in post-operative length of stay or need for inpatient rehabilitation post-discharge by psychosocial characteristics. After a mean follow-up of 2.2 ±1.8 years, 94 (78% of the 120 who survived the LVAD implantation hospitalization) patients had been re-hospitalized (range 0–15 per person, mean 1.3 per person*year follow-up) and 67 (59%) had died. There were 8 patients (5.8%) that subsequently received a heart transplant. In three patients the issue that originally precluded them from transplant listing was alcohol (n=1) or recent tobacco use (n=2), and they were able to be listed after a period of abstinence. Two additional patients who were not transplant candidates prior to LVAD due to recent tobacco use have since been listed and are awaiting transplant.

Psychosocial Characteristics and Death

We found no significant association between psychosocial characteristics at the time of LVAD implantation and death (Table 2). There was no difference in the risk of death in patients with depression whether they were or were not on an anti-depressant at the time of LVAD implantation (p value for interaction= 0.71). There was no association between PHQ-9 scores and death. There was no association between the primary contraindication to transplant and death.

Table 2.

Psychosocial Characteristics and Outcomes After LVAD

| Unadjusted | *Adjusted | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | P value | HR (95% CI) | P value | |

| Death | ||||

| Married/partner | 1.27 (0.65–2.48) | 0.49 | 1.46 (0.68–3.13) | 0.33 |

| Current tobacco use | 0.36 (0.11–1.14) | 0.082 | 0.39 (0.12–1.26) | 0.11 |

| Heavy alcohol use/abuse | 1.40 (0.71–2.75) | 0.33 | 1.77 (0.86–3.64) | 0.12 |

| Illegal drug use | 0.94 (0.34–2.58) | 0.90 | 1.03 (0.32–3.32) | 0.97 |

| Depression | 1.45 (0.88–2.38) | 0.15 | 1.51 (0.90–2.52) | 0.12 |

| Post-high school education | 1.30 (0.76–2.21) | 0.34 | 1.30 (0.75–2.25) | 0.36 |

| Private insurance | 0.97 (0.55–1.68) | 0.90 | 1.07 (0.60–1.91) | 0.82 |

| Distance from implant center† | 1.26 (0.77–2.05) | 0.36 | 1.33 (0.81–2.19) | 0.25 |

| Readmission | ||||

| Married/partner | 1.10 (0.83–1.46) | 0.50 | 1.08 (0.78–1.50) | 0.65 |

| Current tobacco use | 0.65 (0.43–0.98) | 0.042 | 0.57 (0.38–0.88) | 0.010 |

| Heavy alcohol use/abuse | 1.32 (0.96–1.79) | 0.084 | 1.26 (0.91–1.75) | 0.17 |

| Illegal drug use | 1.67 (1.17–2.39) | 0.005 | 1.55 (1.01–2.35) | 0.043 |

| Depression | 1.72 (1.38–2.15) | <0.001 | 1.77 (1.40–2.22) | <0.001 |

| Post-high school education | 0.74 (0.58–0.95) | 0.012 | 0.82 (0.64–1.07) | 0.14 |

| Private insurance | 1.00 (0.78–1.27) | 0.17 | 0.99 (0.77–1.27) | 0.92 |

| Distance from implant center† | 0.65 (0.53–0.81) | <0.001 | 0.64 (0.51–0.80) | <0.001 |

All models are adjusted for age, sex, and Charlson comorbidity index. Readmission models are also adjusted for distance from implant center

Distance from implant center >median

Psychosocial Characteristics and Readmission

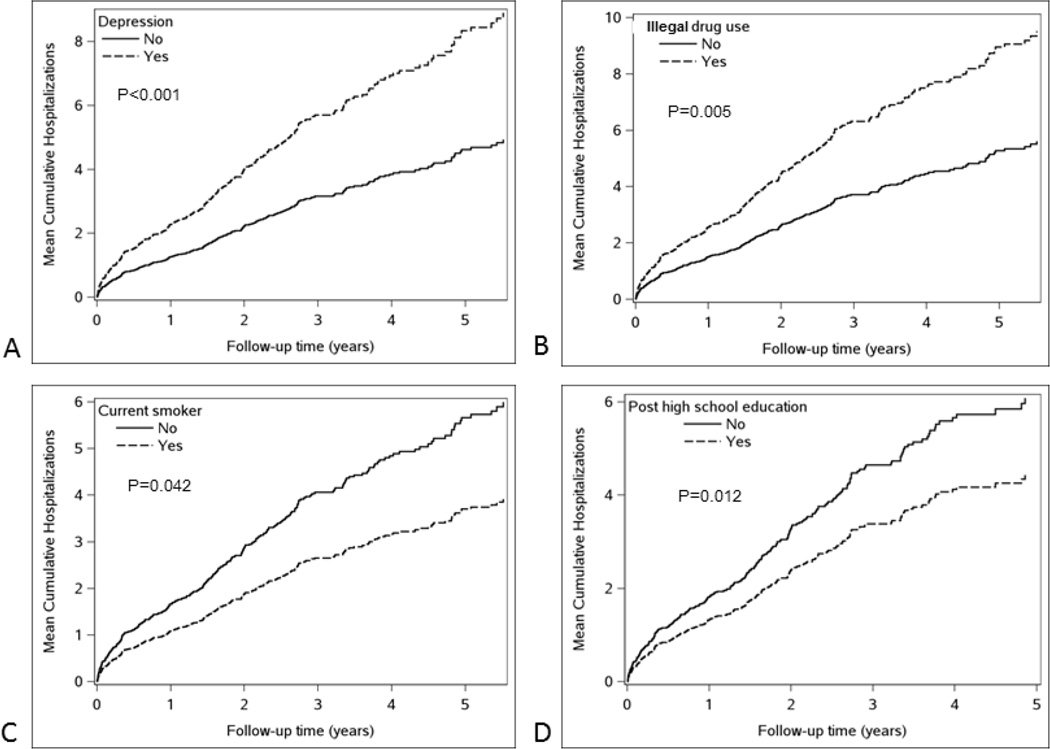

In total, there were 387 readmissions over the course of follow-up. The most common reasons for readmissions were gastrointestinal disorders including bleeding (15.8%), ventricular arrhythmias (12.1%), heart failure (12.0%), driveline-related issues including infection and fracture (8.0%), and hemolysis/suspected LVAD thrombus (5.2%). The association between psychosocial characteristics and readmission are shown in Table 2 and the Figure. Prior to adjusting for potential confounders, illegal drug use (HR 1.67, 95% CI 1.17–2.39) and depression (HR 1.72, 95% CI 1.38–2.15) were associated with higher readmission risk, while a post-high school education (HR 0.74, 95% CI 0.58–0.95) and current tobacco use (HR 0.65, 95% CI 0.43–0.98) were associated with lower readmission risk. In addition, living further from the implanting center was associated with a lower risk of readmission. However, this may be due to the fact that we are unable to capture readmissions to other hospitals, and patients that live further away may be more likely to be readmitted elsewhere. To minimize potential confounding, we adjusted for distance from implanting center in all of our readmission models. After adjusting for age, sex, comorbidity, and distance from implanting center, both illegal drug use (HR 1.55, 95% CI 1.01–2.35) and depression (HR 1.77, 95% CI 1.40–2.22) remained associated with higher readmission risk. Current tobacco use was associated with a lower risk of readmission (HR 0.57, 95% CI 0.38–0.88). Education level was no longer associated with readmission risk. The attenuation of the association between education level and readmission risk was primarily related to adjustment for the Charlson comorbidity index. There was no association between PHQ-9 scores and readmission risk.

Figure. Cumulative Readmissions Over Time by Psychosocial Characteristics.

The estimated mean cumulative readmissions over time by depression (A), illegal drug use (B), current tobacco use (C) and post-high school education (D) are shown.

Differences in the proportion of cause-specific readmission according to psychosocial factors are shown in Table 3. Patients with illegal drug use were disproportionately admitted for hemolysis and driveline-related issues (35.0% of total admissions for drug-users vs. 10.6% for non-drug users, p<0.001), and only rarely for heart failure or ventricular arrhythmias (5.0% of total admissions for drug users vs. 26.0% for non-drug users, p=0.002). Current tobacco users experienced a low number of readmissions overall, but had a lower proportion for GI bleeding (p=0.041), and a higher proportion for driveline-related issues (p=0.033). Patients with post-high school education experienced a lower proportion of readmissions for hemolysis (p=0.019) and married patients had a lower proportion of readmissions for ventricular arrhythmias (p=0.004).

Table 3.

Cause-Specific Proportion of Readmissions According to Psychosocial Factors

| GI Disorders |

Heart Failure |

Ventricular Arrhythmias |

Driveline Infection/ Fracture |

Hemolysis/ LVAD thrombus |

Stroke | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | 61 (15.8) | 45 (11.6) | 47 (12.1) | 31 (8.0) | 20 (5.2) | 14 (3.6) |

| Married/partner | ||||||

| Yes | 55 (16.5) | 41 (12.3) | 34 (10.2)† | 27 (8.1) | 18 (5.4) | 13 (3.9) |

| No | 6 (11.1) | 4 (7.4) | 13 (24.1) | 4 (7.4) | 2 (3.7) | 1 (1.9) |

| Current tobacco user | ||||||

| Yes | 1 (3.1)* | 1 (3.1) | 7 (21.9) | 6 (18.8)* | 2 (6.3) | 1 (3.1) |

| No | 60 (16.9) | 44 (12.4) | 40 (11.3) | 25 (7.0) | 18 (5.1) | 13 (3.7) |

| Heavy alcohol use/abuse | ||||||

| Yes | 8 (11.8) | 5 (7.4) | 4 (5.9) | 8 (11.8) | 5 (7.4) | 3 (4.4) |

| No | 53 (16.6) | 40 (12.5) | 43 (13.5) | 23 (7.2) | 15 (4.7) | 11 (3.4) |

| Illegal drug use | ||||||

| Yes | 3 (7.5) | 1 (2.5)* | 1 (2.5)* | 7 (17.5)* | 7 (17.5)† | 2 (5.0) |

| No | 58 (16.7) | 44 (12.7) | 46 (13.3) | 24 (6.9) | 13 (3.7) | 12 (3.5) |

| Depression | ||||||

| Yes | 30 (18.5) | 21 (13.0) | 17 (10.5) | 10 (6.2) | 9 (5.6) | 4 (2.5) |

| No | 31 (13.8) | 24 (10.7) | 30 (13.3) | 21 (9.3) | 11 (4.9) | 10 (4.4) |

| Post-high school education | ||||||

| Yes | 15 (11.9) | 20 (15.9) | 18 (14.3) | 12 (9.5) | 2 (1.6)† | 5 (4.0) |

| No | 34 (18.3) | 19 (10.2) | 17 (9.1) | 18 (9.7) | 15 (8.1) | 5 (2.7) |

| Private health insurance | ||||||

| Yes | 19 (20.7) | 8 (8.7) | 13 (14.1) | 10 (10.9) | 6 (6.5) | 3 (3.3) |

| No | 42 (14.2) | 37 (12.5) | 34 (11.5) | 21 (7.1) | 14 (4.7) | 11 (3.7) |

Values shown are N(% of total readmissions for patients with the psychosocial characteristic shown).

Difference in proportion of readmissions *p<0.05 and †p<0.025 in patients with vs. without the psychosocial characteristic

DISCUSSION

This study was the first to comprehensively assess the association between baseline psychosocial characteristics and outcomes after DT LVAD implantation. We found that several psychosocial characteristics are predictive of readmission. A history of illegal drug use and depression are associated with a higher risk of readmission, while tobacco use is associated with lower readmission risk. Psychosocial characteristics were not significant predictors of mortality.

Depression was very common pre-DT LVAD, occurring in nearly one-third of patients. This is not surprising, as clinically significant depression is present in at least one in five heart failure patients6, 15, and 18% of patients were noted to have a history of a mood disorder prior to LVAD implantation at another institution16. While depression has been associated with worse outcomes in patients with heart failure6 and those undergoing cardiac transplantation7, whether depression was associated with worse outcomes in patients undergoing DT LVAD was unclear. Herein, we found that depression was associated with increased risk of readmission in patients undergoing DT LVAD. While not a significant predictor of death, the hazard ratio for death was 1.51 for depression, and our relatively small number of deaths limited our power to detect a difference. These findings support the fact that depression is not a benign condition and can be associated with worse outcomes after LVAD. Depression can result in modified behavior such as medical non-compliance17 which could contribute to a need for hospitalization. While our study does not provide insight as to whether treatment of depression results in improved outcomes, it underscores the need for appropriate identification and consideration of depression in risk-stratification and communication of risk prior to DT LVAD.

We also found that illegal drug use was associated with increased readmission risk. Most patients were former users, with only a few having active use at the time of LVAD implantation. This is the second report to find that illegal drug use is associated with worse outcomes after LVAD, as Cogswell et al reported a higher risk of death and driveline infection in patients with active substance abuse at their center9. As such, drug use appears to be consistently associated with increased risk for adverse outcomes after LVAD. We also found that patients with drug use were disproportionately readmitted for hemolysis and driveline-related issues, problems that may be more influenced by compliance with site care and anticoagulation compared with other causes of readmission. Further work is needed to understand whether additional treatment and counseling is helpful in mitigating this risk.

We were surprised to find that current tobacco use was associated with lower risk of readmission. It is possible that current tobacco users were deemed ineligible for transplant due to tobacco use rather than other comorbidities and, therefore, represent a lower-risk group. This may also represent another example of the “smoker’s paradox”, whereby smokers fare better than their non-smoking counterparts after presenting with a medical condition. After acute myocardial infarction, this is felt to result from the fact that smokers develop coronary artery disease as a result of smoking rather than other comorbidities, and thus have better survival as they are “healthier” than their counterparts18.

We found no association between psychosocial characteristics and mortality. This may be due to the relatively small patient population, although this is the largest study to date assessing such characteristics. Psychosocial characteristics are known to affect behavior, which may result in increased care-seeking (e.g. readmissions) but have less effect on outcomes such as death. However, further work is needed in larger populations of patients to confirm our findings.

We found no association between health insurance coverage and outcomes. This is in contrast to reports in the general heart failure population, where privately insured patients tend to have lower readmission rates than patients with government insurance19. Similarly, we found no association between marital status and outcomes. As LVAD patients are generally required to have a caregiver to help them post-operatively even if unmarried, it is not surprising that marital status was not a strong predictor of outcomes in this population. However, more educated patients had a lower risk of readmission, though this was mitigated by adjustment for comorbidities. Patients with greater health literacy are known to have better compliance with medical therapy20 and lower healthcare utilization including hospitalizations21.

Strengths and Limitations

There are several limitations that are important to understand when interpreting these data. Our study is retrospective in nature and includes only patients at a single medical center. Psychosocial variables were defined based on medical record documentation. The prevalence of some characteristics such as alcohol and illegal drug use may be underestimated due to patient unwillingness to disclose information. However, it is notable that patients were evaluated by a social worker prior to LVAD and information was gathered from both patients and family members. Finally, patients who receive DT LVAD are still selected and the criteria used for selection may vary by center. The association between psychosocial characteristics and outcomes may differ at centers that implant LVADs in patients with a different psychosocial risk pattern. Finally, readmissions at other institutions were not captured in this study. However, recent data suggests that 86% of readmissions after LVAD are to the implanting hospital22. In addition to the limitations, there are several notable strengths. This is the first study to extensively assess the association between psychosocial characteristics and outcomes. In addition to capturing the association with death, this study also examined hospital readmission, which is an important concern after LVAD implantation.

Clinical Implications

There are important clinical implications of these data. Patients with a history of depression and illegal drug use are at higher risk for readmission after DT LVAD, and these factors should be considered in risk stratifying patients prior to surgery. It is important to identify such characteristics as medical intervention may lessen the burden and improve patient outcomes.

Conclusion

Psychosocial characteristics are associated with risk of readmission after DT LVAD implantation. A thorough assessment of psychosocial characteristics should be an important component of the evaluation and risk stratification of patients for DT LVAD. Further work is needed to understand whether addressing psychosocial factors prior to DT LVAD modifies risk.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

FUNDING SOURCES, Dr. Dunlay’s research is supported by the NIH (K23 HL 116643).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

DISCLOSURES. The authors have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

All authors have approved the final article.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lietz K, Long JW, Kfoury AG, et al. Outcomes of left ventricular assist device implantation as destination therapy in the post-REMATCH era: implications for patient selection. Circulation. 2007;116(5):497–505. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.691972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lund LH, Matthews J, Aaronson K. Patient selection for left ventricular assist devices. Eur J Heart Fail. 2010;12(5):434–443. doi: 10.1093/eurjhf/hfq006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rogers JG, Bostic RR, Tong KB, Adamson R, Russo M, Slaughter MS. Cost-effectiveness analysis of continuous-flow left ventricular assist devices as destination therapy. Circ Heart Fail. 2012;5(1):10–16. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.111.962951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Slaughter MS, Meyer AL, Birks EJ. Destination therapy with left ventricular assist devices: patient selection and outcomes. Curr Opinion Cardiol. 2011;26(3):232–236. doi: 10.1097/HCO.0b013e328345aff4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Khazanie P, Hammill BG, Patel CB, et al. Trends in the use and outcomes of ventricular assist devices among medicare beneficiaries, 2006 through 2011. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63(14):1395–1404. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.12.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moraska AR, Chamberlain AM, Shah ND, et al. Depression, healthcare utilization, and death in heart failure: a community study. Circ Heart Fail. 2013;6(3):387–394. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.112.000118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zipfel S, Schneider A, Wild B, et al. Effect of depressive symptoms on survival after heart transplantation. Psychosom Med. 2002;64(5):740–747. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000031575.42041.6a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maltby MC, Flattery MP, Burns B, Salyer J, Weinland S, Shah KB. Psychosocial assessment of candidates and risk classification of patients considered for durable mechanical circulatory support. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2014;33(8):836–841. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2014.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cogswell R, Smith E, Hamel A, et al. Substance abuse at the time of left ventricular assist device implantation is associated with increased mortality. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2014 Oct;33(10):1048–1055. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2014.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bruce CR, Delgado E, Kostick K, et al. Ventricular assist devices: a review of psychosocial risk factors and their impact on outcomes. J Card Fail. 2014 Dec;20(12):996–1003. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2014.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Feldman D, Pamboukian SV, Teuteberg JJ, et al. The 2013 International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation Guidelines for mechanical circulatory support: executive summary. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2013 Feb;32(2):157–187. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2012.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Center for Disease Control and Prevention; [Accessed December 4, 2014]. Alcohol and public health: Frequently asked questions. http://www.cdc.gov/alcohol/faqs.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gottdiener JS, Bednarz J, Devereux R, et al. American Society of Echocardiography recommendations for use of echocardiography in clinical trials. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2004;17(10):1086–1119. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2004.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stevenson LW, Pagani FD, Young JB, et al. INTERMACS profiles of advanced heart failure: the current picture. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2009 Jun;28(6):535–541. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2009.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rutledge T, Reis VA, Linke SE, Greenberg BH, Mills PJ. Depression in heart failure a meta-analytic review of prevalence, intervention effects, and associations with clinical outcomes. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;48(8):1527–1537. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.06.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Reynard AK, Butler RS, McKee MG, Starling RC, Gorodeski EZ. Frequency of depression and anxiety before and after insertion of a continuous flow left ventricular assist device. Am J Cardiol. 2014;114(3):433–440. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2014.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.DiMatteo MR, Lepper HS, Croghan TW. Depression is a risk factor for noncompliance with medical treatment: meta-analysis of the effects of anxiety and depression on patient adherence. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160(14):2101–2107. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.14.2101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Andrikopoulos GK, Richter DJ, Dilaveris PE, et al. In-hospital mortality of habitual cigarette smokers after acute myocardial infarction; the "smoker's paradox" in a countrywide study. Eur Heart J. 2001;22(9):776–784. doi: 10.1053/euhj.2000.2315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Allen LA, Smoyer Tomic KE, Smith DM, Wilson KL, Agodoa I. Rates and predictors of 30-day readmission among commercially insured and Medicaid-enrolled patients hospitalized with systolic heart failure. Circ Heart Fail. 2012;5(6):672–679. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.112.967356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Noureldin M, Plake KS, Morrow DG, Tu W, Wu J, Murray MD. Effect of health literacy on drug adherence in patients with heart failure. Pharmacotherapy. 2012;32(9):819–826. doi: 10.1002/j.1875-9114.2012.01109.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mitchell SE, Sadikova E, Jack BW, Paasche-Orlow MK. Health literacy and 30-day postdischarge hospital utilization. J Health Communication. 2012;17(Suppl 3):325–338. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2012.715233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dunlay SM, Haas LR, Herrin J, et al. Use of Post-acute Care Services and Readmissions After Left Ventricular Assist Device Implantation in Privately Insured Patients. J Card Fail. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2015.06.012. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]