Synopsis

Mycophenolic acid (MPA) is an immunosuppressive drug produced by several fungi in Penicillium subgenus Penicillium. This toxic metabolite is an inhibitor of IMP dehydrogenase (IMPDH). The MPA biosynthetic cluster of P. brevicompactum contains a gene encoding a B-type IMPDH, IMPDH-B, which confers MPA-resistance. Surprisingly, all members of subgenus Penicillium contain genes encoding IMPDHs of both the A and B type, regardless of their ability to produce MPA. Duplication of the IMPDH gene occurred prior to and independent of the acquisition of the MPA biosynthetic cluster. Both P. brevicompactum IMPDHs are MPA-resistant while the IMPDHs from a nonproducer are MPA-sensitive. Resistance comes with a catalytic cost: while P. brevicompactum IMPDH-B is >1000-fold more resistant to MPA than a typical eukaryotic IMPDH, its value of kcat/Km is 0.5% of “normal”. Curiously, IMPDH-B of Penicillium chrysogenum, which does not produce MPA, is also a very poor enzyme. The MPA binding site is completely conserved among sensitive and resistant IMPDHs. Mutational analysis shows that the C-terminal segment is a major structural determinant of resistance. These observations suggest that the duplication of the IMPDH gene in Pencillium subgenus Penicillium was permissive for MPA production and that MPA production created a selective pressure on IMPDH evolution. Perhaps MPA production rescued IMPDH-B from deleterious genetic drift.

Keywords: IMPDH, gene duplication, Penicillium, mycophenolic acid, neofunctionalization, drug resistance

Introduction

Filamentous fungi produce a vast arsenal of toxic natural products that require the presence of corresponding defense mechanisms to avoid self-intoxication. The importance of these defense mechanisms is demonstrated by the presence of resistance genes within biosynthetic gene clusters, yet how production and resistance co-evolved is poorly understood. Insights into the inhibition of enzymes involved in self-resistance provide an intriguing strategy for the development of antifungal agents. Further, the elucidation of the defense mechanisms is required for the design of heterologous cell factories producing bioactive compounds.

Self-resistance can involve expression of a target protein that is impervious to the toxic natural product, which suggests that resistance originates from a gene duplication event. The biosynthetic cluster of the immunosuppressive drug mycophenolic acid (MPA) offers an intriguing example of this phenomenon. MPA is a well-characterized inhibitor of IMP dehydrogenase (IMPDH) [1], and the P. brevicompactum MPA biosynthetic cluster contains a second type of IMPDH gene that confers MPA-resistance (IMPDH-B/mpaF; [2, 3]). Curiously, both MPA producers and non-producers in Penicillium subgenus Penicillium contain two IMPDH genes encoding IMPDH-A and IMPDH-B [3]. Phylogenetic analysis suggests that the gene duplication event occurred before or simultaneous with the radiation of Penicillium subgenus Penicillium [2, 3]. How this gene duplication event influenced the acquisition of MPA biosynthesis is not understood.

Here we investigate the relationship between MPA production, MPA resistance and the properties of IMPDH-A and IMPDH-B. While IMPDH-B from the producer organism P. brevicompactum is extraordinarily resistant to MPA, IMPDH-B from the nonproducer P. chrysogenum displays typical sensitivity. Both IMPDH-Bs are very poor enzymes, but P. chrysogenum IMPDH-B is almost nonfunctional. These observations suggest that acquisition of the MPA biosynthetic cluster may have rescued IMPDH-B from deleterious genetic drift.

Experimental

Fungal strains

P. brevicompactum IBT23078, P. chrysogenum IBT5857, A. nidulans IBT27263, and the 11 strains listed in Supplementary Table S1, were grown on Czapek yeast extract agar (CYA) at 25°C [4].

MPA treatment of fungi

Spores from P. brevicompactum IBT23078, P. chrysogenum IBT5857 and A. nidulans IBT27263 were harvested and suspended in sterile water. 10 μl of serial 10-fold spore dilutions were spotted on CYA plates with or without 200 μg/ml MPA. All plates contained 0.8 % (v/v) methanol. Stock solution (25 mg/ml MPA in methanol) and MPA plates were made briefly before the spores were spotted on the plates in order to avoid MPA degradation. MPA was acquired from Sigma.

RNA purification and cDNA synthesis

Spores from P. brevicompactum IBT23078 were harvested and used to inoculate 200 ml yeast extract sucrose (YES) medium in 300 ml shake flasks without baffles [4]. P. brevicompactum was grown at 25°C and 150 rpm shaking. After 48 hours the mycelium was harvested and RNA was purified using the Fungal RNA purification Miniprep Kit (E.Z.N.A) and cDNA was synthesized from the RNA using Finnzymes Phusion™ RT-PCR Kit according to the instructions of the two manufactures.

Plasmid construction

Constructs for expression of His-tagged IMPDHs in E. coli were created by inserting the IMPDH CDSs into a pET28a that had been converted into a USER compatible vector (Figure S1). pET28U was created by PCR amplifying pET28 with the primers 527/528 followed by DpnI treatment to remove the PCR template (Figure S1). The P. brevicompactum IMPDH-B gene was amplified from cDNA from P. brevicompactum. Genes encoding A. nidulans IMPDH-A (AnIMPDH-A), P. brevicompactum IMPDH-A (PbIMPDH-A), P. chrysogenum IMPDH-A (PcIMPDH-A) and P. chrysogenum IMPDH-B (PcIMPDH-B) were obtained from gDNA. In all cases, the three exons of each gene were individually PCR amplified and purified and subsequently USER fused using a method previously described [5, 6]).

The expression constructs for chimeric and mutated IMPDHs were created by fusing the two parts of the IMPDHs using the USER fusion method to introduce the mutation in the primer tail [6]. Chimeric IMPDH of PbIMPDH-B (N-term) and PbIMPDH-A (C-term) was created by USER fusing two P. brevicompactum IMPDH-B and IMPDH-A fragments, which were PCR amplified with primer-pairs 529/667 and 668/540, respectively, into pET28U as described above. Similarly, chimeric IMPDH of PbIMPDH-A (N-term) and PbIMPDH-B (C-term) was created by amplifying PbIMPDH-A and PbIMPDH-B fragments with primer-pairs 539/669 and 670/530, respectively , followed by USER fusing into pET28U. Using gDNA from the proper source, the Y411F (Chinese hamster ovary IMPDH2 numbering) mutation was introduced into A. nidulans IMPDH-A and into P. brevicompactum IMPDH-A and B by amplifying and fusing two IMPDH fragments with primers 545/359 and 546/358; 539/455 and 540/454; and 529/361 and 530/360, respectively. For details on primers see Tables S2 and S3. The PfuX7 polymerase was used for PCR amplification in all cases [7].

Cladistic analysis

Alignment of DNA coding regions and protein were performed with Clustal W implemented in the CLC DNA workbench 6 (CLC bio) using the following parameters: gap open cost = 6.0, gap extension cost = 1.0, and end gap cost = free. A cladogram was constructed with the same software using the neighbour-joining method and 1000 bootstrap replicates [PMID: 3447015]. The DNA sequence of IMPDH and β-tubulin from selected fungi were either generated by degenerate PCR (dPCR, Supplementary Table S1) or retrieved from NCBI. A. nidulans β-tubulin [GenBank:XM_653694], IMPDH-A DNA sequence [GenBank: BN001302 (ANIA_10476)], Coccidioides immitis β-tubulin [GenBank: XM_001243031], IMPDH-A DNA sequence [GenBank: XM_001245054], P. bialowiezense IBT21578 β-tubulin [GenBank:JF302653], IMPDH-A DNA sequence [GenBank:JF302658], IMPDH-B DNA sequence [GenBank:JF302662], P. brevicompactum IBT23078 β-tubulin [GenBank:JF302653], IMPDH-A DNA sequence [GenBank:JF302657], P. carneum IBT3472 β-tubulin [GenBank:JF302650], IMPDH-A DNA sequence [GenBank:JF302656], IMPDH-B DNA sequence [GenBank:JF302660],)], P. chrysogenum IBT5857 β-tubulin [GenBank:XM_002559715], IMPDH-A DNA sequence [GenBank:XM_002562313], IMPDH-B DNA sequence[GenBank:XM_002559146], P. paneum IBT21729 β-tubulin [GenBank:JF302651], IMPDH-A DNA sequence [GenBank:JF302654], IMPDH-B DNA sequence [GenBank:JF302661], P. roqueforti IBT16406 β-tubulin [GenBank:JF302649], IMPDH-A DNA sequence [GenBank:JF302655], IMPDH-B DNA sequence [GenBank:JF302659]. The MPA gene cluster sequence from P. brevicompactum IBT23078, which contains the IMPDH-B gene sequence (mpaF) is available from GenBank under accession number [GenBank:HQ731031]. Full length protein sequences were retrieved from NCBI under the following accessions Candida albicans: [GenBank: EEQ46038], Chinese hamster IMPDH2 [GenBank:P12269], E. coli [GenBank:ACI80035], Human IMPDH type 2 [GenBank:NP_000875], P. chrysogenum IMPDH-A gene [GenBank: CAP94756], IMPDH-B [GenBank:CAP91832], Yeast IMD2 [GenBank:P38697], IMD3 [GenBank:P50095], IMD4 [GenBank:P50094].

Degenerate PCR

Primers and PCR conditions for amplifying part of the genes encoding IMPDH-A, IMPDH-B and beta-tubulin sequence was as described in [3]. Genomic DNA from 11 fungi from the Penicillium subgenus Penicillium sub-clade (Table S1) were extracted using the FastDNA® SPIN for Soil Kit (MP Biomedicals, LLC). PCR primer pairs 236HC/246HC or 531/532 were used to amplify DNA from the gene encoding IMPDH-A. The primer pair 240 HC/241 HC was used to amplify DNA from the gene encoding IMPDH-B, and the primer pair 343/344 was used to amplify β-tubulin.

Expression and purification of His-tagged proteins

Plasmids were expressed in a ΔguaB derivative of E. coli BL21(DE3) [8]. Cells were grown in LB medium at 30°C until OD600 = 1.0 for AnImdA and 1.5 for all other enzymes, and induced overnight at 16°C with 0.5 mM IPTG for AnImdA and 0.1 mM IPTG for all other enzymes. Cells were harvested by centrifugation and resuspended in buffer containing 20 mM Na2HPO4, 500 mM NaCl, 5 mM β-mercaptoethanol, 5 mM imidazole and Complete protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany). Cell lysates were prepared by sonication followed by centrifugation. All enzymes were purified using a HisTrap affinity column (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ) on an AKTA Purifier (Amersham Biosciences, GE Healthcare Piscataway, NJ) and dialyzed into buffer containing 50 mM Tris, pH 8.0, 100 mM KCl, 1 mM DTT and 10% glycerol. All enzymes were purified to >90% purity as determined by SDS-PAGE with the exception of PcIMPDH-B, which was partially purified to ~45% purity due to poor expression and stability (Figure S2).

Enzyme concentration determination

Enzyme concentration was determined by the BioRad assay according to manufacturer's instructions using IgG as a standard. The BioRad assay overestimates IMPDH concentration by a factor of 2.6 [9]. Concentration of active enzyme was determined by MPA titration using an equation for tight binding inhibition (eq 1).

| (1) |

Enzyme assays

Standard IMPDH assay buffer consists of 50 mM Tris, pH 8.0, 100 mM KCl, 1 mM DTT, and varying concentrations of IMP and NAD+ (concentrations used for each enzyme is listed in Table S4. Enzyme activity was measured by monitoring the production of NADH by changes in absorbance increase at 340 nm on a Cary Bio-100 UV-vis spectrophotometer at 25°C (ε340 = 6.2 mM−1 cm−1). MPA inhibition assays were performed at saturating IMP and half-saturating NAD+ concentrations to avoid complications arising from NAD+ substrate inhibition. IMP-independent reduction of NAD+ was observed in the partially purified preparation of PcIMPDH-B at ~25% of the rate in the presence of IMP. The rate of this background reaction was subtracted from rate with IMP for each MPA concentration. Initial velocity data obtained by fitting to either the Michaelis-Menten equation (eq 2) or an uncompetitive substrate inhibition equation (eq 3) using SigmaPlot (Systat Software, Inc.).

| (2) |

| (3) |

Bacterial complementation assays

Cultures were grown overnight in LB medium with 25 μg/ml kanamycin. 5 μl of 1:20 serial dilutions were plated on M9 minimal media containing 0.5% casamino acids, 100 μg/ml L-tryptophan, 0.1% thiamin, 25 μg/ml kanamycin, and 66 μM IPTG. Guanosine supplemented plates contain 50 μg/ml guanosine. MPA plates contain 100 μM MPA. Plates were incubated overnight at 37°C and then grown at room temperature.

Sequences generated in this study

See Table S1 for GenBank accession numbers.

Results

The presence of IMPDH-B is not linked to MPA biosynthesis

The first gene encoding IMPDH-B was identified in P. brevicompactum where it is part of the MPA biosynthetic cluster and confers MPA resistance (P. brevicompactum IMPDH-B is also known as mpaF) [2]. Of the full genome sequences currently available for filamentous fungi, only P. chrysogenum (the sole representative of Penicillium subgenus Penicillium) contains an IMPDH-B gene. We previously analyzed 4 other fungi in Penicillium subgenus Penicillium for the presence of IMPDH genes, and all contain both IMPDH-A and IMPDH-B [3]. We have now expanded this search to include 11 additional Penicillium strains of the Penicillium subgenus. Degenerate PCR analysis revealed that all 11 strains contain both genes encoding IMPDH-A and IMPDH-B (Supplementary Table S1 and Figure S3), suggesting that the presence of IMPDH-B is widespread in species of Penicillium subgenus Penicillium, even though many of these strains do not produce MPA [10]).

It is possible that these MPA non-producer strains may contain latent or cryptic MPA biosynthetic genes. A previously described example is that although P. chrysogenum does not produce viridicatumtoxin, griseofulvin and tryptoquialanine, it does contain sequence regions with high identity to these biosynthetic clusters, which suggests that these gene functions were lost during evolution [11, 12]. Likewise, P. chrysogenum does not produce MPA. However, in this case BLAST searches failed to identify any genes with significant sequence identity to the MPA biosynthesis gene cluster in P. chrysogenum. These searches did identify an IMPDH-B pseudogene in P. chrysogenum. This 260 bp gene fragment has highest identity to IMPDH-B from P. chrysogenum (77%) and 64% identity to IMPDH-B from P. brevicompactum.

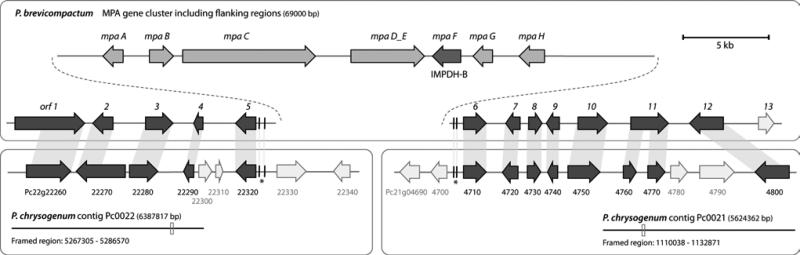

We analyzed the regions surrounding the MPA biosynthetic cluster in P. brevicompactum and used BLAST searches to identify similar genes in P. chrysogenum. In this way, adjacent genes that are highly similar and syntenic to genes found in P. chrysogenum were identified (Figure 1). Interestingly, the genes flanking one side of the cluster correspond to a locus on contig Pc0022, while the other side of the cluster corresponds to a locus located at another contig, Pc0021. Regions further away from the MPA cluster in P. brevicompactum contain additional homologs to P. chrysogenum genes, but these genes are located in many different contigs (Table S5). P. chrysogenum contains small sequence regions with high identity to the flanking region of the MPA cluster. This identity is in the promoter regions and most likely represents conserved regulatory regions. Despite a detailed search, we found no sequence similarity to the regions around the PcIMPDH-B and the pseudo IMPDH-B (Pc22g07570) (data not shown). Together these findings suggest that the MPA cluster has never been present in P. chrysogenum and that a high degree of genome shuffling has occurred since the divergence of P. brevicompactum and P. chrysogenum.

Figure 1. Flanking regions of the MPA-biosynthesis gene cluster.

P. brevicompactum and the corresponding syntenic loci on P. chrysogenum contig Pc0022 and Pc0021 are shown. Regions marked with (*) indicate short conserved sequences (length < 53 bp, identity > 86%).

PbIMPDH-B is MPA-resistant, but PcIMPDH-B is MPA-sensitive

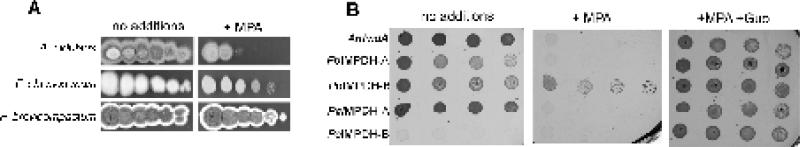

The PbIMPDH-B gene confers MPA resistance on A. nidulans, suggesting that MPA resistance might be a common feature of all IMPDH-B proteins [3]. Consistent with this hypothesis, P. chrysogenum is less sensitive to MPA than A. nidulans, though significantly more sensitive than P. brevicompactum (Figure 2A). These observations suggest that P. chrysogenum IMPDH-B may be semi-resistant to MPA.

Figure 2. MPA resistance in fungi and bacteria expressing fungal IMPDHs.

A. Spot assay to determine sensitivity towards MPA. A ten-fold dilution series of spores from the A. nidulans, P. chrysogenum and P. brevicompactum were grown on CYA plates containing no additives or 6.2 μM MPA. The spot with the highest number of spores in each row contains ~106 spores. B. E. coli ΔguaB was cultured on minimal media supplemented with 100 μM MPA, no additions or 50 μg/ml guanosine and 100 μM MPA.

To further investigate this hypothesis, IMPDHs from P. brevicompactum, P. chrysogenum and A. nidulans were heterologously expressed as N-terminal His6-tagged proteins in an E. coli ΔguaB strain that lacks endogenous IMPDH; these enzymes are denoted PbIMPDH-A, PbIMPDH-B, PcIMPDH-A, PcIMPDH-B and AnImdA (Figure 2B). All strains grow on minimal media in the presence of guanosine (Figure 2B). Bacteria expressing AnImdA, PbIMPDH-A, PbIMPDH-B and PcIMPDH-A grow on minimal media in the absence of guanosine, indicating that active IMPDHs were expressed in all four cases. Only bacteria expressing PbIMPDH-B were resistant to MPA (Figure 2B). PcIMPDH-B failed to grow on minimal media in the absence of guanosine, suggesting that this protein was not able to complement the guaB deletion. This observation suggests that PcIMPDH-B may be nonfunctional.

All five fungal IMPDHs were isolated to further investigate the molecular basis of MPA resistance. With the exception of PcIMPDH-B, all enzymes were purified to >90% purity in one step using a nickel affinity column (Figure S2). PcIMPDH-B was unstable and could only be purified to ~45% homogeneity. Western blot analysis using anti-human IMPDH2 polyclonal antibodies showed that PcIMPDH-B had undergone proteolysis. This degradation could not be prevented by the inclusion of protease inhibitor cocktails during the purification. We performed MPA titrations to determine the concentration of active enzyme in all five protein samples. MPA traps an intermediate in the IMPDH reaction, so that only active enzyme will bind MPA [13]. All of the proteins were ~100% active with the exception of PcIMPDH-B, which was 48% active as expected. The oligomeric states of AnImdA, PbIMPDH-A and PbIMPDH-B were examined by gel filtration chromatography. All three enzymes eluted at a molecular weight of approximately 220 kDa, consistent with being tetramers (Figure S3).

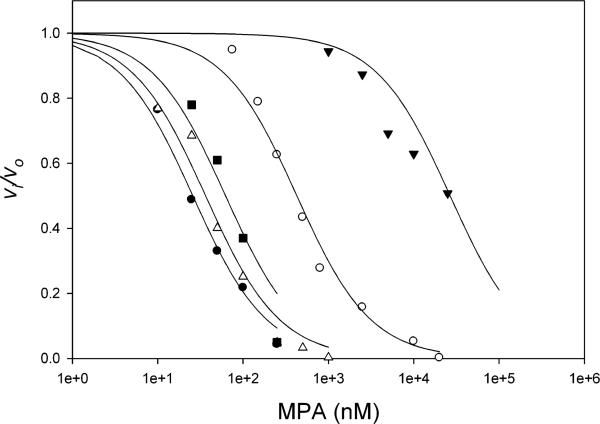

AnImdA, PcIMPDH-A and PcIMPDH-B are all sensitive to MPA, with values of IC50 ranging from 26-60 nM (Figure 3 and Table 1). Similar MPA inhibition has been reported for the mammalian and C. albicans enzymes [13, 14]. These observations indicate that MPA resistance is not a general property of IMPDH-Bs.

Figure 3. MPA inhibition of fungal IMPDHs.

AnImdA, closed circles, PbIMPDH-A, open circles, PbIMPDH-B, closed triangles, PcIMPDH-A, open triangles, PcIMPDH-B, closed squares.

Table 1. Characterization of IMPDHs from filamentous fungi.

Data analyzed as described in Materials and Methods. n.a., not applicable. PbIMPDH-B and PcIMPDH-B did not show NAD+ substrate inhibition up to 5 mM. The concentrations of IMP and NAD+ used for IC50 determination for each enzyme is included in the Supporting information.

| IC50 (MPA) (μM) | kcat (s−1) | KM (IMP) (μM) | kcat/KM (IMP) (M−1s−1) | KM (NAD+) (μM) | kcat/KM (NAD) (M−1s−1) | Kü (NAD+) (mM) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AnImdA | 0.026 ± 0.002 | 0.74 ± 0.06 | 10 ± 1 | 74,000 ± 8,000 | 170 ± 70 | 4,400 ± 100 | 1.5 ± 0.6 |

| PbIMPDH-A | 0.43 ± 0.03 | 0.70 ± 0.08 | 130 ± 30 | 5,400 ± 1,200 | 340 ± 90 | 2,100 ± 900 | 4.7 ± 1.1 |

| PbIMPDH-B | 27 ± 9 | 0.41 ± 0.02 | 1,400 ± 200 | 300 ± 80 | 790 ± 140 | 500 ± 100 | n.a. |

| PcIMPDH-A | 0.036 ± 0.004 | 0.84 ± 0.03 | 40 ± 6 | 21,000 ± 2,000 | 290 ± 60 | 2900 ± 300 | 2.4 ± 0.5 |

| PcIMPDH-B | 0.06 ± 0.01 | 0.0075 ± 0.001 | 600 ± 300 | 12 ± 3 | 640 ± 130 | 11 ± 6 | n.a. |

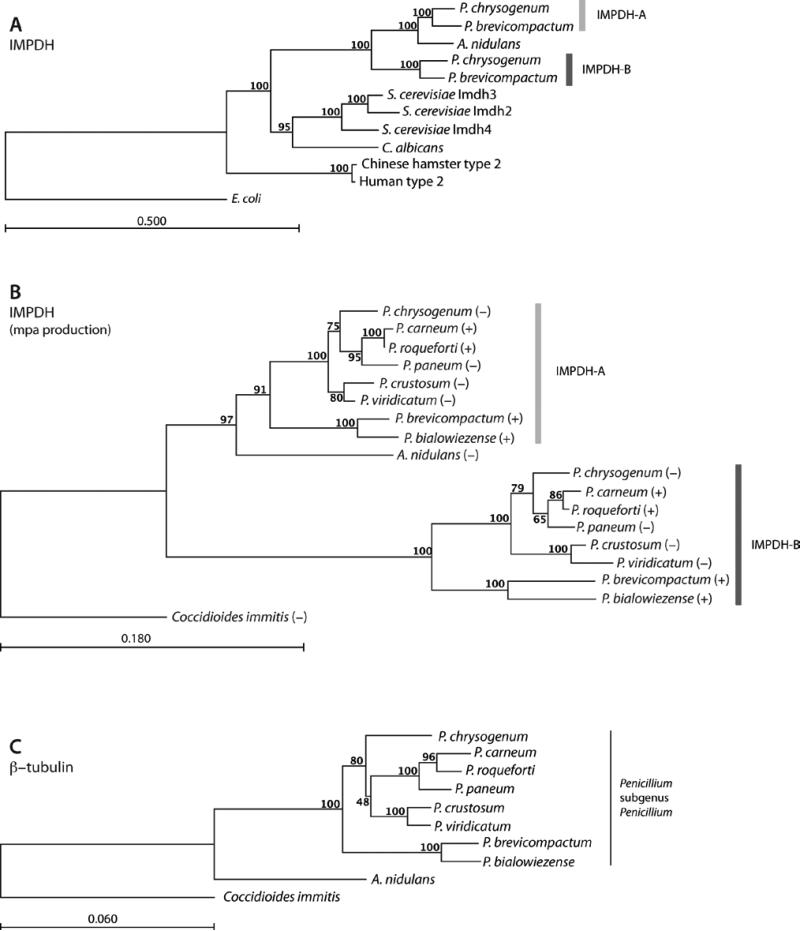

MPA is a poor inhibitor of both PbIMPDH-A and PbIMPDH-B (Figure 3 and Table 1). PbIMPDH-A is 10-fold more resistant than IMPDHs from the other filamentous fungi while PbIMPDH-B is a remarkable ~103-fold more resistant. Thus the ability of P. brevicompactum to proliferate while producing MPA can be explained by the intrinsic resistance of its target enzymes. These observations suggest that MPA production creates a selective pressure on IMPDH evolution. Curiously, similar IC50 values have been reported for Imd2 and Imd3 from Saccharomyces cerevisiae (IC50 = 70 μM and 500 nM for Imd2 and Imd3, respectively;[15]). These enzymes are the only other examples of naturally occurring MPA-resistant IMPDHs from eukaryotes. Cladistic analysis indicates that the S. cerevisiae IMPDHs arose in a distinct gene duplication event (Figure 4). Therefore P. brevicompactum IMPDH-B is unlikely to share a common ancestry with S. cerevisiae Imd2.

Figure 4. IMPDH phylogeny.

A) Rooted cladogram based on full length amino acid sequences. B) and C) Rooted cladograms based on B) IMPDH cDNA sequences (372 – 387 bp) and C) β-tubulin cDNA sequences (950 bp) from eight species from Penicillium subgenus Penicillium and two filamentous fungi outside. P.: Penicillium and A.: Aspergillus. Bootstrap values (expressed as percentage of 1000 replications) are shown at the branch points, and the scale represents changes per unit. In analysis B, MPA production is indicated by “+” or “−“. The sub-clades with Penicillium subgenus Penicillium genes are marked by light gray (IMPDH-A) and dark gray (IMPDH-B). E. coli has been used as outgroup in analysis A, and Coccidioides immitis as outgroup in analyses B and C.

IMPDH-Bs are very poor IMPDHs

The reactions of the fungal IMPDHs were characterized to determine how MPA resistance affects enzymatic function. The values of kcat are similar for AnImdA, PcIMPDH-A, PbIMPDH-A and PbIMPDH-B and generally typical for eukaryotic IMPDHs (Table 1, [13]). Typical values of KM (NAD+) and KM (IMP) are also observed for AnImdA and PcIMPDH-A; the values of KM for PbIMPDH-A are high, but not unprecedented. In contrast, the value of KM(IMP) = 1.4 mM for PbIMPDH-B is ~100-fold higher than the highest value reported for any other IMPDH. Like PbIMPDH-B, PcIMPDH-B exhibits an abnormally high value of KM (IMP). The value of kcat of PcIMPDH-B is more than a factor of 100 less than those of the other fungal IMPDHs. The corresponding values of kcat/KM are the lowest ever observed for an IMPDH by factors of 103 (IMP) and 200 (NAD+) (see [13] for compilation of values). Therefore both IMPDH-Bs are inferior enzymes.

Identification of a major determinant of MPA resistance

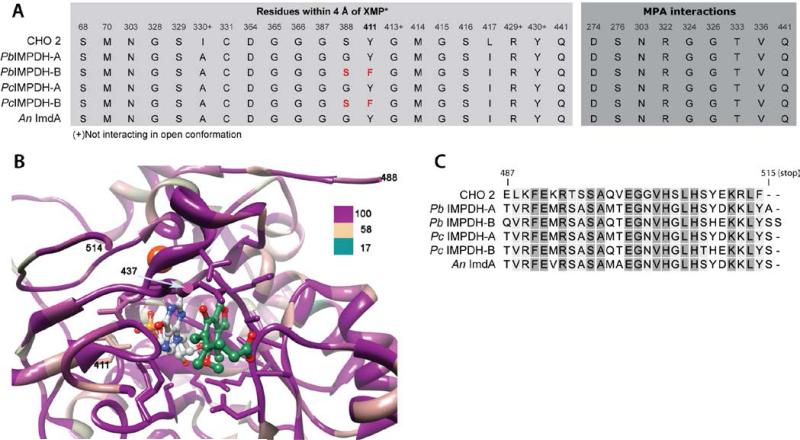

MPA inhibits IMPDHs by an unusual mechanism [16]. The IMPDH reaction proceeds via the covalent intermediate E-XMP*, which forms when the active site cysteine residue attacks the C2 position of IMP, transferring a hydride to NAD+ [13]. The resulting NADH dissociates, allowing MPA to bind to E-XMP*, preventing hydrolysis to form XMP. The crystal structure of the E-XMP*•MPA complex has been solved for Chinese hamster IMPDH type 2 [17], revealing that MPA stacks against the purine ring of E-XMP* in a similar manner to the nicotinamide of NAD+. Surprisingly, all of the residues within 4 Å of MPA are completely conserved in the fungal IMPDHs (Figure 5). Likewise, the IMP binding site is also highly conserved. Only residue 411 is variable (Chinese hamster ovary IMPDH2 numbering); the IMPDH-A enzymes contain a tyrosine residue at this site, while IMPDH-B enzymes have phenylalanine residues (Figure 5). Substitution of Tyr411 with Phe did not increase the MPA resistance of PbIMPDH-A, nor did the Phe411 to Tyr substitution decrease the MPA resistance of PbIMPDH-B (Table 2). Therefore the structural determinants of MPA resistance must reside outside the active site.

Figure 5. The MPA binding site is conserved among drug sensitive and drug resistant eukaryotic IMPDHs.

A) An alignment of IMPDH-A and IMPDH-B from P. brevicompactum 23078 and P. chrysogenum, IMPDH-A from A. nidulans and IMPDH2 from Chinese hamster was mapped onto the x-ray crystal structure of the MPA complex of Chinese hamster IMPDH (PDB accession 1JR1 [17]. 100% conserved, dark magenta; 58% conserved, tan; 17% conserved, dark cyan. MPA, green ball and stick; IMP intermediate, gray ball and stick; K+, gold; residues within 4 Å of MPA and IMP are shown in stick.

B) Amino acid polymorphism in IMPDH of A. nidulans (An), P. brevicompactum (Pb) and P. chrysogenum (Pc). Shown are residues within 4 Å of XMP* and MPA.

C) Alignment of the C-terminal region. The region aligned in the figure represents the fragments that were swapped in the chimerics of PbIMPDH-A and PbIMPDH-B. Underlined: residues that are polymorphic.

Table 2. MPA inhibition of fungal IMPDH variants.

Residue Phe411 is substituted with Tyr in IMPDH-B and residue Tyr411 is substituted with Phe in IMPDH-A. nd, no data.

| IC50 (μM) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WT | 411* | C-terminal swap | C-terminal + 411* | |

| PbIMPDH-A | 0.43 ± 0.03 | 0.16 ± 0.02 | 3 ± 0.2 | 4.1 ± 0.3 |

| PbIMPDH-B | 27 ± 9 | 25 ± 2 | 4.1 ± 0.3 | 3.1 ± 0.3 |

| AnImdA | 0.026 ± 0.002 | 0.026 ± 0.002 | nd | nd |

Inspection of the structure suggested that the C-terminal segment (residues 498-527) was another likely candidate for a structural determinant of MPA resistance (Figure 5). This region includes part of the site that binds a monovalent cation activator, as well as segments that interact with the active site residues. Deletion of this segment inactivates the enzyme [18]. Swapping the 30 residue C-terminal segments revealed that this region is responsible for ~7 of the 60-fold difference in MPA resistance between PbIMPDH-A and PbIMPDH-B, see Table 2. Additional structural determinants of MPA resistance remain to be identified.

Discussion

Phylogenetic analysis indicates that the IMPDH gene was duplicated prior to the radiation of Penicillium subgenus Penicillium (Figure 4 and Figure S4). No remnants of the MPA biosynthetic cluster are present in P. chrysogenum, which suggests that the ability to produce MPA arrived after duplication of the IMPDH genes. Consistent with this hypothesis, both IMPDHs from the MPA-producer P. brevicompactum are more resistant to MPA than the IMPDHs from A. nidulans and P. chrysogenum. Thus, both P. brevicompactum IMPDH-A and IMPDH-B have evolved in response to the presence of MPA. PbIMPDH-B is 1000x more resistant than typical eukaryotic IMPDHs. The structural basis of these functional differences is not readily discerned. Whereas prokaryotic IMPDHs contain substitutions in their active sites that can account for MPA-resistance, no such substitutions are present in the P. brevicompactum IMPDHs. The substitution of Ser or Thr for Ala249 is associated with MPA resistance in C. albicans and S. cerevisiae [14, 15]. This substitution is found in PbIMPDH-A, but not in the more resistant PbIMPDH-B. Substitutions at positions 277 and 462 have also resulted in modest MPA resistance [19], and substitutions at 351 are proposed to cause resistance [20], but again no correlation is observed in the fungal IMPDHs. We identified the C-terminal segment as a new structural determinant of MPA sensitivity, but this segment accounts for only 7x of the 60x difference in resistance between PbIMPDH-B and PbIMPDH-B. Importantly, the extraordinary resistance of PbIMPDH-B comes with a catalytic cost as this enzyme has lost much of the catalytic power of a typical IMPDH, with values of Km(IMP) that are ~100x greater and kcat/Km(IMP) that are 102-103x lower than “normal”. This observation suggests that PbIMPDH-B would be a very poor catalyst at normal cellular IMP concentrations of 20-50 μM [21]. However, IMP concentrations increase 10-35 fold in the presence of MPA [1, 22, 23]. Thus P. brevicompactum may contain millimolar concentrations of IMP during MPA biosynthesis, so that the turnover of PbIMPDH-B would be comparable to a “normal” fungal IMPDH.

Curiously, MPA production does not follow the phylogenetic relationship established by analysis of the IMPDH and beta-tubulin genes (Figure 4). P. chrysogenum does not contain MPA biosynthetic genes although MPA-producers are found on the neighboring branches of the phylogenetic tree. As noted above, P. chrysogenum is more resistant to MPA than A. nidulans (Figure 2A). This resistance could be the result of a gene dosage effect as MPA resistance is associated with amplification of IMPDH genes in several organisms, consistent with this hypothesis [20, 24-27]. We propose that the presence of two IMPDH genes in Pencillium subgenus Penicillium was permissive for MPA production. The failure to observe MPA production in other Pencillium species may reflect inappropriate culture conditions rather than absence of the biosynthetic cluster. If so, it is possible that MPA biosynthesis has been obtained in several independent events. It will be interesting to map the evolution of MPA biosynthesis and resistance as more genomic sequences of filamentous fungi become available.

Gene duplication is generally believed to be a driving force in evolution, allowing one copy to diverge constraint-free while the other copy maintains essential functions. The “escape from adaptive conflict” subfunctionalization model is particularly attractive for the evolution of new enzyme activities [28, 29]. In this model, duplication relieves the constraint of maintaining the original function and allows the emergence of enzymes with new catalytic properties. The blemish in this appealing hypothesis has long been recognized: most mutations are deleterious, so that the extra copy is quickly lost or converted into a pseudogene. Though several elegant and rigorous investigations of the in vitro evolution of new enzyme function demonstrate the feasibility of subfunctionalization (reviewed in [29, 30]), genetic drift is widely recognized as the dominant mechanism in the wider evolution field. Several observations suggest that the emergence of MPA-resistant PbIMPDH-B could be an example of neofunctionalization by a classic Ohno type mechanism - a duplication followed by (largely deleterious) drift until a new environment, MPA production, provides a selection.

PcIMPDH-B displays the effects of deleterious genetic drift: this protein is labile to proteolysis, and the value of kcat ~1% of that of typical eukaryotic IMPDH. Microarray data indicate that P. chrysogenum expresses both IMPDH-A and IMPDH-B under most conditions, so at present there is no evidence for specialized functions for these genes [31, 32]. We cannot rule out that PcIMPDH-B plays another role within the cell, perhaps by interacting with another protein, or even as a heterotetramer with PcIMPDH-A. Nevertheless, our data suggest that the enzymatic properties of both IMPDH-Bs have declined over the course of evolution. In the case of P. brevicompactum, gaining the ability to produce MPA may have rescued IMPDH-B from nonfunctionalization.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Martin Engelhard Kornholt for valuable technical assistance in the laboratory.

Funding

This work was supported by The Danish Council for Independent Research Technology and Production Sciences [09-064967 and 09-064240 (BGH and UHM)] and by National Institutes of Health [GM054403 (LH)].

Abbreviations used

- IMPDH

inosine-5’-monophosphate dehydrogenase

- IMP

inosine 5’-monophosphate

- NAD+

nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide

- MPA

mycophenolic acid

- AnImdA

IMPDH from Aspergillus nidulans

- PbIMPDH-A

IMPDH-A from Penicillium brevicompactum

- PbIMPDH-B

IMPDH-B from P. brevicompactum

- PcIMPDH-A

IMPDH-A from Penicillium chrysogenum

- PcIMPDH-B

IMPDH-B from P. chrysogenum

Footnotes

The final version of record is available at http://www.biochemj.org/content/441/1/219.long

References

- 1.Bentley R. Mycophenolic Acid: A One Hundred Year Odyssey from Antibiotic to Immunosuppressant. Chem. Rev. 2000;100:3801–3826. doi: 10.1021/cr990097b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Regueira TB, Kildegaard KR, Hansen BG, Mortensen UH, Hertweck C, Nielsen J. Molecular Basis for Mycophenolic Acid Biosynthesis in Penicillium brevicompactum. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2011;77:3035–3043. doi: 10.1128/AEM.03015-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hansen BG, Genee HJ, Kaas CS, Nielsen JB, Mortensen UH, Frisvad JC, Patil KR. A new clade of IMP dehydrogenases with a role in self-resistance inmycophenolic acid producing fungi. BMC Microbiol. 2011 doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-11-202. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Frisvad JC, Samson RA. Polyphasic taxonomy of Penicillium subgenus Penicillium - A guide to identification of food and air-borne terverticillate Penicillia and their mycotoxins. Stud. Mycol. 2004:1–173. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Geu-Flores F, Nour-Eldin HH, Nielsen MT, Halkier BA. USER fusion: a rapid and efficient method for simultaneous fusion and cloning of multiple PCR products. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:e55. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hansen BG, Salomonsen B, Nielsen MT, Nielsen JB, Hansen NB, Nielsen KF, Regueira TB, Nielsen J, Patil KR, Mortensen UH. Versatile Enzyme Expression and Characterization System for Aspergillus nidulans, with the Penicillium brevicompactum Polyketide Synthase Gene from the Mycophenolic Acid Gene Cluster as a Test Case. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2011;77:3044–3051. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01768-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Norholm MH. A mutant Pfu DNA polymerase designed for advanced uracil-excision DNA engineering. BMC Biotechnol. 2010;10:21. doi: 10.1186/1472-6750-10-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.MacPherson IS, Kirubakaran S, Gorla SK, Riera TV, D'Aquino JA, Zhang M, Cuny GD, Hedstrom L. The structural basis of Cryptosporidium -specific IMP dehydrogenase inhibitor selectivity. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:1230–1231. doi: 10.1021/ja909947a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang W, Papov VV, Minakawa N, Matsuda A, Biemann K, Hedstrom L. Inactivation of inosine 5′-monophosphate dehydrogenase by the antiviral agent 5-ethynyl-1-β-D-ribofuranosylimidazole-4-carboxamide 5′-monophosphate. Biochemistry. 1996;35:95–101. doi: 10.1021/bi951499q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Frisvad JC, Smedsgaard J, Larsen TO, Samson RA. Mycotoxins, drugs and other extrolites produced by species in Penicillium subgenus Penicillium. Stud. Mycol. 2004:201–241. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chooi YH, Cacho R, Tang Y. Identification of the viridicatumtoxin and griseofulvin gene clusters from Penicillium aethiopicum. Chem. Biol. 2010;17:483–494. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2010.03.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gao X, Chooi YH, Ames BD, Wang P, Walsh CT, Tang Y. Fungal indole alkaloid biosynthesis: genetic and biochemical investigation of the tryptoquialanine pathway in Penicillium aethiopicum. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:2729–2741. doi: 10.1021/ja1101085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hedstrom L. IMP Dehydrogenase: structure, mechanism and inhibition. Chem. Rev. 2009;109:2903–2928. doi: 10.1021/cr900021w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kohler GA, Gong X, Bentink S, Theiss S, Pagani GM, Agabian N, Hedstrom L. The functional basis of mycophenolic acid resistance in Candida albicans IMP dehydrogenase. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:11295–11302. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M409847200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jenks MH, Reines D. Dissection of the molecular basis of mycophenolate resistance in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast. 2005;22:1181–1190. doi: 10.1002/yea.1300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Link JO, Straub K. Trapping of an IMP dehydrogenase-substrate covalent interemediate by mycophenolic acid. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1996;118:2091–2092. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sintchak MD, Fleming MA, Futer O, Raybuck SA, Chambers SP, Caron PR, Murcko M, Wilson KP. Structure and mechanism of inosine monophosphate dehydrogenase in complex with the immunosuppressant mycophenolic acid. Cell. 1996;85:921–930. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81275-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nimmesgern E, Black J, Futer O, Fulghum JR, Chambers SP, Brummel CL, Raybuck SA, Sintchak MD. Biochemical analysis of the modular enzyme inosine monophosphate dehydrogenase. Protein Expression and Purification. 1999;17:282–289. doi: 10.1006/prep.1999.1136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Farazi T, Leichman J, Harris T, Cahoon M, Hedstrom L. Isolation and characterization of mycophenolic acid resistant mutants of inosine 5′monophosphate dehydrogenase. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:961–965. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.2.961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lightfoot T, Snyder FF. Gene amplification and dual point mutations of mouse IMP dehydrogenase associated with cellular resistance to mycophenolic acid. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1994;1217:156–162. doi: 10.1016/0167-4781(94)90029-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hartman N, Ahluwalia G, Cooney D, Mitsuya H, Kageyama S, Fridland A, Broder S, Johns D. Inhibitors of IMP dehydrogenase stimulate the phosphorylation of the anti-human immunodeficiency virus nucleosides 2′,3′-dideoxyadenosine and 2′,3′-dideoxyinosine. Mol. Pharm. 1991;40:118–124. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Balzarini J, Karlsson A, Wang L, Bohman C, Horska K, Votruba I, Fridland A, VanAershot A, Hedewijn P, DeClerq E. Eicar (5-ethynyl-1-b-D-ribofuranosylimidazole-4-carboxamide) a novel potent inhibitor of inosinate dehydrogenase activity and guanylate biosynthesis. J. Biol. Chem. 1993;33:24591–24598. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wu JC. Mycophenolate mofetil: molecular mechanisms of action. Pers. Dru Disc. Des. 1994;2:185–204. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Collart FR, Huberman E. Amplification of the IMP dehydrogenase gene in Chinese hamster cells reistant to mycophenolic acid. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1987;7:3328–3331. doi: 10.1128/mcb.7.9.3328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wilson K, Collart F, Huberman E, Stringer J, Ullman B. Amplification and molecular cloning of the IMP dehydrogenase gene of Leishmania donovani. J. Biol. Chem. 1991;266:1665–1671. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wilson K, Berens RL, Sifri CD, Ullman B. Amplification of the inosinate dehydrogenase gene in Trypanosoma brucei gambienese due to an increase in chromosome copy number. J. Biol. Chem. 1994;269:28979–28987. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kohler GA, White TC, Agabian N. Overexpression of a cloned IMP dehydrogenase gene of Candida albicans confers resistance to the specific inhibitor mycophenolic acid. J. Bact. 1997;179:2331–2338. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.7.2331-2338.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.O'Brien PJ, Herschlag D. Catalytic promiscuity and the evolution of new enzymatic activities. Chem. Biol. 1999;6:R91–R105. doi: 10.1016/S1074-5521(99)80033-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Khersonsky O, Tawfik DS. Enzyme promiscuity: a mechanistic and evolutionary perspective. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2010;79:471–505. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-030409-143718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tracewell CA, Arnold FH. Directed enzyme evolution: climbing fitness peaks one amino acid at a time. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2009;13:3–9. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2009.01.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.van den Berg MA, Albang R, Albermann K, Badger JH, Daran JM, Driessen AJ, Garcia-Estrada C, Fedorova ND, Harris DM, Heijne WH, Joardar V, Kiel JA, Kovalchuk A, Martin JF, Nierman WC, Nijland JG, Pronk JT, Roubos JA, van der Klei IJ, van Peij NN, Veenhuis M, von Dohren H, Wagner C, Wortman J, Bovenberg RA. Genome sequencing and analysis of the filamentous fungus Penicillium chrysogenum. Nat. Biotechnol. 2008;26:1161–1168. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hoff B, Kamerewerd J, Sigl C, Zadra I, Kuck U. Homologous recombination in the antibiotic producer Penicillium chrysogenum: strain DeltaPcku70 shows up-regulation of genes from the HOG pathway. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2010;85:1081–1094. doi: 10.1007/s00253-009-2168-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.