Abstract

Peptide immunotherapy (PIT) is a targeted therapeutic approach, involving administration of disease-associated peptides, with the aim of restoring antigen-specific immunological tolerance without generalized immunosuppression. In type 1 diabetes, proinsulin is a primary antigen targeted by the autoimmune response, and is therefore a strong candidate for exploitation via PIT in this setting. To elucidate the optimal conditions for proinsulin-based PIT and explore mechanisms of action, we developed a preclinical model of proinsulin autoimmunity in a humanized HLA-DRB1*0401 transgenic HLA-DR4 Tg mouse. Once proinsulin-specific tolerance is broken, HLA-DR4 Tg mice develop autoinflammatory responses, including proinsulin-specific T cell proliferation, interferon (IFN)-γ and autoantibody production. These are preventable and quenchable by pre- and post-induction treatment, respectively, using intradermal proinsulin-PIT injections. Intradermal proinsulin-PIT enhances proliferation of regulatory [forkhead box protein 3 (FoxP3+)CD25high] CD4 T cells, including those capable of proinsulin-specific regulation, suggesting this as its main mode of action. In contrast, peptide delivered intradermally on the surface of vitamin D3-modulated (tolerogenic) dendritic cells, controls autoimmunity in association with proinsulin-specific IL-10 production, but no change in regulatory CD4 T cells. These studies define a humanized, translational model for in vivo optimization of PIT to control autoimmunity in type 1 diabetes and indicate that dominant mechanisms of action differ according to mode of peptide delivery.

Keywords: antigens/peptides/epitopes, autoimmunity, diabetes, regulatory T cells, T cells

Introduction

Type 1 diabetes is a T cell-mediated autoimmune disease, characterized by the progressive loss of immunological tolerance to β cell antigens 1. This results in the destruction of β cells in the pancreas and the requirement for lifelong insulin replacement therapy. At diagnosis a significant proportion of β cell mass may remain, and identification of immunotherapeutic approaches that can specifically halt and reverse the autoimmune process to preserve β cells, without generalized immunosuppression, remains a key objective in type 1 diabetes treatment and prevention 2. Proinsulin is one of the primary β cell autoantigens targeted by autoreactive CD4+ T and B lymphocytes in the early phases of the disease 3–7. Specifically combating these responses using antigen-specific immunotherapy (ASI) may be an effective approach for redirecting the autoimmune response prior to, or immediately after, clinical manifestation. Among the different ASI options, administration of peptides representing naturally processed and presented epitopes of a dominant antigen such as proinsulin is an attractive strategy (peptide immunotherapy: PIT) 8.

Human diseases for which peptide-based immunotherapies are under investigation include clinical allergy, rheumatoid arthritis, multiple sclerosis and type 1 diabetes 9–12. Early-stage development of PIT in the relevant clinical setting has provided encouraging indications that this approach has the ability to modify the autoimmune response, via analysis of both surrogate and clinical outcomes. In addition, there have been efforts to develop preclinical models to enable biomarker development, optimization of dose, peptide sequence, peptide number, route of administration and number and frequency of injections, as well as to elucidate mechanisms of action 13. In this respect, the field of autoimmunity has progressed at a slower rate than allergy, with limited availability of appropriate and representative humanized animal models with which to optimize the potential power of this treatment modality while using the same peptide sequences that may be delivered in the clinic.

We therefore explored the utility of a preclinical model of proinsulin autoimmunity in a humanized HLA-DRB1*0401 transgenic HLA-DR4 Tg mouse. The HLA-DRB1*0401 gene confers significant risk of type 1 diabetes and approximately half of patients carry this genotype 14,15. Here we use this model to examine the tolerogenic potential of HLA-DR4 restricted proinsulin peptide-based therapeutic strategies. Our studies focus on proinsulin mono- and multi-peptide therapy, delivered by injection and monopeptide therapy delivered using vitamin D3 (VD3)-modulated tolerogenic dendritic cells (tol-DCs) 16,17. We tested these potential therapeutic strategies for their ability to reverse pre-existing proinsulin autoimmunity in vivo, mirroring the clinical intervention setting for their future use. We show that the success of multi-PIT therapy depends upon the number of peptides used and frequency of dosing, and is associated with regulatory T cell (Treg) proliferation and enhanced antigen-specific Treg function. In contrast, tol-DC peptide delivery is associated with antigen-specific interleukin (IL)-10 secretion. We conclude that modelling proinsulin autoimmunity has important utility in demonstrating the mode of action in vivo and the immunomodulatory potential of proinsulin-based immunotherapies, aiding their translation into the clinical setting.

Materials and methods

Animals

B6.129S2-H2-Ab1tm1Gru Tg (HLA-DRA/H2-Ea, HLA-DRB1*0401/H2-Eb) 1Kito mice (HLA-DR4 Tg) were imported from Taconic (Germantown, NY, USA) and were used in all experiments 18. All animals were specified pathogen-free and maintained under standard conditions at King's College London Biological Services Unit in accordance with Home Office Regulations.

Induction of proinsulin-specific autoimmunity

Mice were challenged subcutaneously (s.c.) at the tail base with 100 μg human proinsulin protein (Biomm, Belo Horizonte, Brazil) emulsified in complete Freund's adjuvant (CFA; Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO, USA). Mice were treated with 200 ng pertussis toxin (PTX; Sigma-Aldrich) delivered via the intraperitoneal cavity at the time of immunization and 1 day later. In some experiments, mice were boosted with 100 μg of proinsulin emulsified in incomplete Freund's adjuvant (IFA; Sigma-Aldrich) s.c. at the tail base. Where indicated, 100 μg ovalbumin (OVA; Worthington Biochemical Corporation, Lakewood, NJ, USA) or haemagglutinin (HA 306-318; Thermo Electronics, Ulm, Germany) was included in the boost.

Peptides and mono/multi-peptide immunotherapy

Naturally processed and presented HLA-DR4 peptides of human proinsulin C13-32 (GGGPGAGSLQPLALEGSLQK), C19-A3 (GSLQPLALEGSLQKRGIV), C22-A5 (QPLALEGSLQKRGIVEQ), mouse proinsulin C13-32 (GGGPGAGDLQTLALEVARQK), C19-A3 (GDLQTLALEVARQKRGIV), C22-A5 (QTLALEVARQKRGIVDQ) and control haemagglutinin (HA) peptide (PKYVKQNTLKLAT) were all provided by Thermo Scientific (Fremont, CA, USA) at 97% purity 19; 1 μg or 10 μg of proinsulin peptide(s) or control HA peptide was delivered in 100 μl sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) by intradermal injection over the abdomen, once weekly for 4 weeks.

Proliferation assay

Draining lymph nodes (DLNs), including inguinal and para-aortic, were homogenized using a BD Cell Strainer (BD Biosciences, Oxford, UK) (70 μm). Cells were washed in RPMI and resuspended at 2.5 × 106 cells/ml in RPMI containing 0·5% autologous mouse serum. Cells (2·5 × 105) were added to each well of a U-bottomed plate. Cells were restimulated with medium alone, α-CD3α-CD28 dynabeads (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA), proinsulin protein (Biomm) or peptides (Thermo). At 48 h supernatants were removed for cytokine analysis and 0·5 mCi/well [3H]-tritiated thymidine was added. The cells were harvested 18 h later using a MicroBeta Trilux machine (Perkin Elmer, Beaconsfield, UK). In the case of carboxyfluorescein succinimidyl ester (CFSE) dilution assay experiments, cells were first incubated with 1 μmol CFSE (Invitrogen) for 10 min at 37°C. Labelling was quenched using 1 ml fetal calf serum (FCS; Invitrogen). Cells were then washed thoroughly, incubated with medium, peptide, protein or dynabeads and proliferation (CFSE dilution) of CD4+ T cells was assessed 96 h later by flow cytometer using a fluorescence activated cell sorter (FACS)Canto III flow cytometer (BD Bioscience). Samples were analysed using FlowJo software (Tree Star, Ashland, OR, USA).

Cytokine enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)/luminex

IFN-γ and IL-10 levels were measured in culture supernatants taken at 48 h using a Ready-SET-Go kit (eBioscience, Hatfield, UK) in accordance with the manufacturer's guidelines. Tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-α and IL-17 levels were measured by cytokine luminex analysis using custom Millipore (Darmstadt, Germany) kits in accordance with the manufacturer's guidelines and samples were analysed on a FLEXMAP 3D.

Proinsulin antibodies

Serum levels of α-proinsulin immunoglobulin (Ig)G1 were measured by a competitive europium-based ELISA, using the reagents and protocol described previously 20. Samples were analysed using a BMG Labtech FLUOstar Omega (BMG Labtech, Ortenberg, Germany) at one well per second.

Flow cytometry

Flow cytometry was performed according to standard protocol. Antibodies [anti-CD4-peridinin chlorophyll (PerCP), anti-forkhead box protein 3 (FoxP3)-allophycocyanin (APC), anti-CD3-phycoerythrin (PE), anti-CD25-fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC), anti-ki67-Pacific Blue (all eBioscience), anti-CD11c-PE cyanin 7 (Cy7), anti-PDL1-PE, anti-CD86-FITC, anti-HLA-APC (all BD Bioscience)] were added to each sample at a dilution of 1 : 100. Intracellular staining was carried out using a standard kit and according to the manufacturer's guidelines (Biolegend, San Diego, CA, USA). Samples were analysed using a FACSCanto III flow cytometer equipped with a 405-nm Violet laser, a 488-nm Argon laser and a 635-nm red diode laser (BD Bioscience) and FlowJo software. Lymphocytes were first identified according to size and granularity using forward- and side-scatter parameters. CD4+ T cells were next identified on the basis of CD3 and CD4 expression. Regulatory T cells were characterized on the basis of high CD25 and FoxP3 expression. Finally, proliferating regulatory CD3+CD4+FoxP3+CD25high T cells were identified on the basis of up-regulation of the nuclear protein, Ki67.

Proinsulin-specific regulation

Tolerance to proinsulin was breached in mice, as described above. Mice then received four weekly intradermal (i.d.) treatments of 1 μg control-PIT or proinsulin multi-PIT (comprising equimolar amounts of C13-22, C19-A3 and C22-A5) before the ongoing autoimmune response to proinsulin was boosted by s.c. injection of proinsulin/IFA. Lymph nodes were removed and CD4+ T cells were isolated by negative selection using a CD4 T cell isolation kit (Miltenyi Biotec, Bisley, UK). Cells were then stained with anti-CD25-FITC (eBioscience) and CD4+ CD25high suppressor T cells were isolated by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) using a BD FACSAria. Responder cells from proinsulin/CFA immunized mice were labelled with CFSE and co-cultured with CD4+ CD25high T cells for 96 h with medium alone, α-CD3α-CD28 dynabeads or proinsulin protein. Proliferation of responder cells (corresponding to CFSE loss) was measured by flow cytometry; % suppression was calculated by:

Vitamin D3-modified tolerogenic dendritic cell culture

To prepare bone marrow (BM)-derived DCs, cell suspensions were obtained from femurs and tibias of female HLA-DR4 Tg mice. The BM cells were cultured in 6-well plates (Corning Costar, Corning, NY, USA) at 1 × 106 cells/well in RPMI containing 10% FCS, IL-4 (40 ng/ml) (Peprotech, Rocky Hill, NJ, USA) and granulocyte–macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) (40 ng/ml) (Peprotech). 1,25(OH)2VitD3 (Sigma-Aldrich) was added to the cultures on days 0 and 3 at a final concentration of 1 × 10−8 M. Fresh medium was added to the cell cultures every 3 days. On day 6, immature DCs were harvested using cold PBS and gentle scraping. DC maturation was induced by 24 h incubation with LPS 100 ng/ml (Sigma-Aldrich) in RPMI containing 0·5% autologous mouse serum. Flow cytometry was performed at day 6 of culture and 24 h following LPS stimulation, to confirm expression of DC markers CD11c, HLA-DR4 and co-stimulatory molecules CD86 and PDL1. On day 7, mature DCs were pulsed with C19-A3 peptide (10 μg/ml) for 2 h before extensive washing with PBS. C19-A3 pulsed and unpulsed vitamin D3 modified DCs were delivered i.d. at 2 × 105 cells/mouse in 100 μl PBS.

Statistics

Results are expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean (s.e.m.). Statistical significance was determined by one-way analysis of variance (anova) or Student's t-test. A value of P < 0·05 was regarded as significant.

Results

HLA-DR4 Tg model of proinsulin autoimmunity

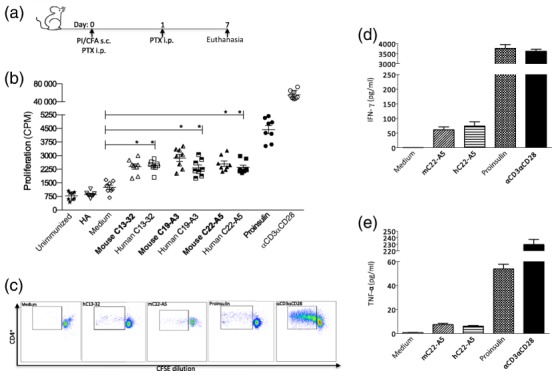

We first developed a humanized model of proinsulin autoimmunity in HLA-DR4 Tg mice, using CFA and PTX to break tolerance (Fig. 1a). To characterize whether proinsulin autoimmunity had been established by this immunization regimen, recall responses were analysed in vitro by measuring proliferation and cytokine production of DLN cell suspensions to human proinsulin protein and HLA-DR4-restricted immunodominant human proinsulin peptides and their murine counterparts (Fig. 1b–e). Priming by this method induced a significant proliferative response to proinsulin protein and peptides of both human and murine origin, as shown by thymidine incorporation (Fig. 1b) and by CFSE dilution of dividing CD4+ T cells (Fig. 1c). In addition, the inflammatory cytokines, IFN-γ and TNF-α, were induced significantly in response to proinsulin protein, human and murine proinsulin peptides with C22-A5 proinsulin peptide shown as a representative example (Fig. 1d,e). Proinsulin autoimmune mice did not show evidence of glucose intolerance or insulitis in these short-term studies when followed-up to 3 months post-autoimmunity induction (data not shown).

Figure 1.

HLA-DR4 Tg mouse model of proinsulin autoimmunity. Mice were immunized subcutaneously (s.c.) with 100 μg proinsulin protein emulsified in complete Freund's adjuvant (CFA). Pertussis toxin was delivered immediately intraperitoneally (i.p.) and 1 day after immunization. Inguinal and para-aortic lymph nodes (LNs) were harvested 7 days later for in vitro analysis (a). Proliferative recall response was measured by thymidine incorporation at 72 h (b) and by carboxyfluorescein succinimidyl ester (CFSE) dilution at 96 h (c). Cytokine luminex analysis was carried out on cell culture supernatants at 48 h to test for the presence of (d) interferon (IFN)-γ, (e) tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-α in response to stimulation of LN cell suspensions to 10 μg/ml murine/human peptides (C22-A5), 50 μg/ml proinsulin protein or positive control αCD3αCD28 dynabeads, as indicated. Data are representative of at least three independent experiments. Bars represent the mean ± standard error of the mean (s.e.m.) *P < 0·05, **P < 0·01, ***P < 0·001; statistical significance was determined by one-way analysis of variance (anova) or Student's t-test, eight mice per group.

Modulating proinsulin autoimmunity with peptide

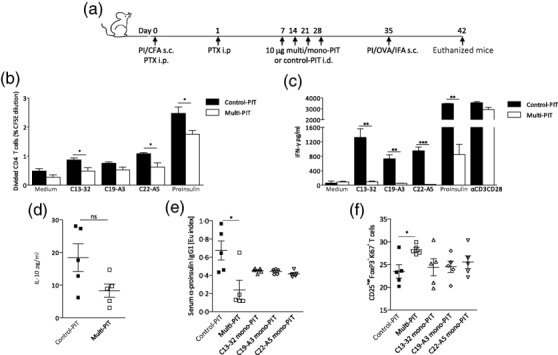

Next, we used this model of proinsulin autoimmunity to assess the capacity of mono- and multi-proinsulin PIT to modulate an established autoimmune response to proinsulin. Proinsulin autoimmunity was established as described in Fig. 1a. The tolerogenic potential of each HLA-DR4-restricted proinsulin peptide was investigated by treating HLA-DR4 Tg mice with four weekly intradermal injections of mono-PIT or multi-PIT (an equimolar cocktail of all three proinsulin peptides) (Fig. 2a). Recall responses were analysed in vitro, following secondary challenge with whole proinsulin-IFA to boost the ongoing autoimmune response (Fig. 2a). Multi-PIT down-modulated the antigen-specific proliferative capacity of DLN cultures significantly in response to proinsulin and proinsulin peptides, but not OVA (Fig. 2b). In addition, multi-PIT decreased the synthesis of the inflammatory mediators IFN-γ (Fig. 2c), IL-17 and IL-13 significantly (data not shown). Interestingly, we did not observe an antigen-specific induction of IL-10 (Fig. 2d). Multi-PIT was also effective at down-modulating the response to proinsulin protein in vivo, as indicated by reduced serum levels of proinsulin-specific IgG (Fig. 2e). In contrast, mono-PIT with C13-32, C19-A3 or C22-A5 showed lower levels of therapeutic potency (Fig. 2e,f).

Figure 2.

Modulating proinsulin autoimmunity with peptide. Tolerance to proinsulin was breached in mice by subcutaneous (s.c.) immunization with 100 μg proinsulin protein emulsified in complete Freund's adjuvant (CFA) and treatment with pertussis toxin intraperitoneally (i.p.) immediately and 1 day after immunization. Mice then received four weekly intradermal (i.d.) treatments of 10 μg control-peptide immunotherapy (PIT) or proinsulin mono/multi-PIT (C13-32; C19-A3; C22-A5), before s.c. immunization with 100 μg proinsulin protein emulsified in incomplete Freund's adjuvant (IFA) to boost the ongoing autoimmune response (a). Lymph nodes (LNs) were harvested 7 days later and LN cell suspensions were cultured with or without proinsulin protein or peptide (C13-32; C19-A3; C22-A5) for 48 h in vitro. Proliferation of CD4+ T cells and interferon (IFN)-γ production were analysed by carboxyfluorescein succinimidyl ester (CFSE) dilution at 96 h (b) and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) at 48 h (c) in response to in vitro stimulation with 50 μg/ml proinsulin protein and 10 μg/ml peptides (C13-32; C19-A3; C22-A5). Mean ± standard error of the mean (s.e.m.) interleukin (IL)-10 production in response to 50 μg/ml proinsulin is shown (d). Serum levels of proinsulin-specific immunoglobulin (Ig)G1 were measured at day 42 (e). Percentages of proliferating CD3+CD4+CD25highforkhead box protein 3 (FoxP3+) regulatory T cells (Tregs) were measured by flow cytometry in LN cultures at day 42 (f). Data are representative of three independent experiments. *P < 0·05, **P < 0·01, ***P < 0·001; statistical significance was determined by one-way analysis of variance (anova) or Student's t-test; (b,c) 15 mice per group; (d–f) five mice per group.

In relation to the mechanism of these effects, analysis of DLNs by flow cytometry demonstrated that the proportion of proliferating Tregs in the lymph nodes following multi-PIT was increased significantly in comparison to control-PIT-treated mice (Fig. 2f). Once again, the combination of three proinsulin peptides delivered as multi-PIT was more effective than mono-PIT at inducing Treg proliferation, suggesting that multiple peptides are more effective than single peptides at modulating an established autoimmune response.

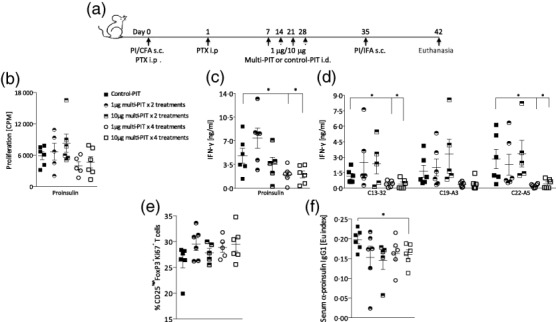

Optimizing modulation of proinsulin autoimmunity with peptide

We next examined how altering the dose or frequency of peptide administration affects the immune modulating potential of PIT. Mice were treated with either 1 or 10 μg of multi-PIT on either two or four occasions (Fig. 3a). To establish the effect of a reduced frequency and/or dose of multi-PIT, recall responses were analysed in vitro by measuring proliferation and cytokine production of DLN cell suspensions to proinsulin protein and proinsulin peptides (Fig. 3b–d). Reducing the number of multi-PIT treatments from four to two resulted in a substantial loss of therapeutic potency. In contrast, four treatments of multi-PIT were effective at down-modulating the response to proinsulin and a reduced dose of 1 μg appeared to be as effective as 10 μg of multi-PIT (Fig. 3b–d). Analysis of DLN composition by flow cytometry, at 7 days post-secondary immunization, revealed an increased level of Treg proliferation in mice that had received multi-PIT in comparison to mice that had received control-PIT, with no significant difference observed between treatment groups (Fig. 3e). Proinsulin-specific serum IgG levels were down-modulated by multi-PIT and were reduced significantly in mice that had received four treatments of 10 μg multi-PIT (Fig. 3f).

Figure 3.

Optimizing modulation of proinsulin autoimmunity with peptide. Increased frequency of low-dose peptide immunotherapy (PIT) is more effective than higher dose or fewer treatments of PIT at reversing the break of tolerance to whole proinsulin. Tolerance to proinsulin was breached in mice by subcutaneous (s.c.) immunization with 100 μg proinsulin protein emulsified in complete Freund's adjuvant (CFA) and treatment with pertussis toxin intraperitoneally (i.p.) immediately and 1 day after immunization. Mice then received four or two weekly intradermal (i.d.) treatments of 10 μg or 1 μg PIT consisting of three proinsulin peptides (C13-32; C19-A3; C22-A5) or control haemagglutinin (HA) peptide, before s.c. immunization with 100 μg proinsulin protein emulsified in incomplete Freund's adjuvant (IFA) to boost the ongoing autoimmune response (a). Lymph nodes (LNs) were harvested at day 42 and LN cells were cultured with or without proinsulin protein or peptide (C13-32; C19-A3; C22-A5) for 48 h in vitro. Proliferation and cytokine production were analysed by thymidine incorporation and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) and the mean ± standard error of the mean (s.e.m.) proliferation in response to 50 μg/ml proinsulin (b) and interferon (IFN)-γ production in response to 50 μg/ml proinsulin (c) or 10 μg/ml proinsulin peptides in draining lymph node (DLN) cultures is shown. Percentage of proliferating CD3+CD4+CD25highFoxP3+ regulatory T cells (Tregs) was measured by flow cytometry in LN cultures at day 42 (e). Serum levels of proinsulin-specific immunoglobulin (Ig)G1 were measured at day 42 (f). Data are representative of at least two independent experiments. *P < 0·05, **P < 0·01, ***P < 0·001; statistical significance was determined by one-way analysis of variance (anova) or Student's t-test, six mice per group.

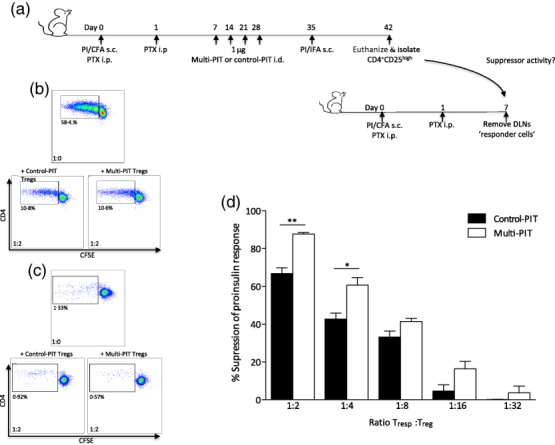

Multi-PIT enhances antigen-specific regulation

We next assessed the impact of multi-PIT on Treg function by measuring proinsulin-specific suppressor activity in the Treg compartment of mice treated with control-PIT compared to those receiving active treatment. CD4+CD25high Tregs were isolated from mice treated with control-PIT or proinsulin multi-PIT and co-cultured, at varying concentrations, with CFSE-labelled responder T cells from mice immunized with proinsulin/CFA (Fig. 4a). Cells were co-cultured in the presence of anti-CD3/anti-CD28 immunomagnetic beads to measure the capacity of control-PIT and multi-PIT Tregs to suppress a polyclonal response. Tregs generated under both treatment conditions demonstrated equivalent suppressive capacity (Fig. 4b). However, in co-cultures stimulated with proinsulin protein there was distinct treatment-related suppressive capacity (Fig. 4c). Tregs from multi-PIT-treated mice suppressed proinsulin-specific responses to a significantly greater degree than Tregs from control-PIT-treated mice (Fig. 4d).

Figure 4.

Multi-peptide immunotherapy (PIT) enhances antigen-specific regulation. Forkhead box protein 3 (FoxP3+) regulatory T cells (Tregs) from mice treated with proinsulin multi-PIT have enhanced proinsulin-specific suppressor activity compared to control-PIT-treated mice. Tolerance to proinsulin was breached in mice by subcutaneous (s.c.) immunization with 100 μg proinsulin protein emulsified in complete Freund's adjuvant (CFA) and treatment with pertussis toxin intraperitoneally (i.p.) immediately and 1 day after immunization. Mice then received four weekly intradermal (i.d.) treatments of 1 μg PIT consisting of three proinsulin peptides (C13-32; C19-A3; C22-A5) or control haemagglutinin (HA) peptide, before s.c. immunization with 100 μg proinsulin protein emulsified in incomplete Freund's adjuvant (IFA) to boost the ongoing autoimmune response (a). Lymph nodes (LNs) were harvested at day 42 and CD4+CD25high Tregs were isolated and co-cultured, at varying concentrations, with carboxyfluorescein succinimidyl ester (CFSE)-labelled responder T cells from mice immunized with proinsulin/complete Freund's adjuvant (CFA). Cells were co-cultured in the presence of αCD3-αCD28 dynabeads (b) or proinsulin protein (c) and proliferation of responder CD4+ T cells was calculated by measuring CFSE dilution by flow cytometry at 96 h. Mean ± standard error of the mean (s.e.m.) proliferation of CFSE-labelled responder cells in response to 50 μg/ml proinsulin in the presence of decreasing concentrations of CD4+CD25high Tregs from either HA- or proinsulin-PIT-treated mice (d). Statistical significance was determined by one-way analysis of variance (anova) or Student's t-test. *P < 0·05, **P < 0·01, 15 mice per group (pooled LNs).

In vivo efficacy of mono-PIT delivered on VD3-DCs

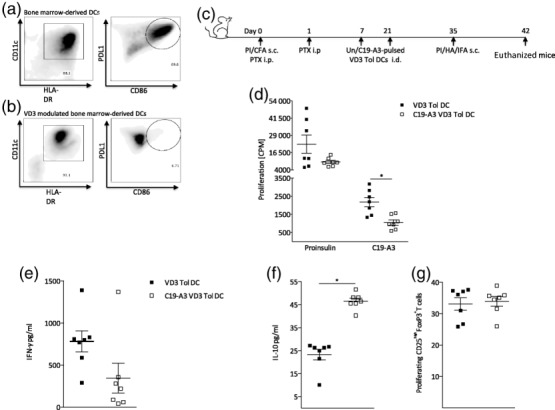

Finally, we used the autoimmunity model to assess the efficacy and mechanism of action of C19-A3 mono-peptide therapy delivered in vivo on the surface of VD3-modulated tolerogenic DCs. BM-derived tol-DCs cultured in the presence of VD3 were monitored by flow cytometry for their expression of cell surface markers. Analysis of untreated (Fig. 5a) or VD3-modulated (Fig. 5b) BM-derived DCs was performed prior to and following LPS maturation. CD11c expression was comparable between untreated and VD3-treated DCs; however, VD3 treatment slightly reduced the expression levels of major histocompatibility complex II (MHCII), consistent with previous reports (Fig. 5a,b) 21. Following LPS maturation, untreated DCs up-regulated both PDL1 and CD86 (Fig. 5a), while VD3-treated DCs expressed programmed death ligand 1 (PDL1) in the absence of CD86. Tolerance to proinsulin was breached in mice that then received two biweekly i.d. treatments of unpulsed or C19-A3-pulsed VD3 tolerogenic DCs. The ongoing autoimmune response was boosted 2 weeks after the final treatment with VD3-DCs (Fig. 5c).

Figure 5.

In vivo efficacy of mono-peptide immunotherapy (PIT) delivered on vitamin D3 (VD3)-DCs. Peptide-loaded VD3-treated tolerogenic dendritic cells (DCs) can reverse the break of tolerance to whole proinsulin. Tolerance to proinsulin was breached in mice by subcutaneous (s.c.) immunization with 100 μg proinsulin protein emulsified in complete Freund's adjuvant (CFA) and treatment with pertussis toxin intraperitoneally (i.p.) immediately and 1 day after immunisation. Mice then received two biweekly i.d. treatments of un- or C19-A3-pulsed VD3 tolerogenic DCs intradermally (i.d.), before s.c. immunization with 100 μg proinsulin protein emulsified in incomplete Freund's adjuvant (IFA) to boost the ongoing autoimmune response. (c). Flow cytometric analysis of untreated (a) or VD3-modulated (b) bone marrow-derived DCs was performed following lipopolysaccharide (LPS) maturation. VD3 did not impair the expression of CD11c, while major histocompatibility complex II (MHCII) levels were decreased slightly but non-significantly. Untreated DCs up-regulate both programmed dearth ligand 1 (PDL1) and CD86 (a), while VD3-treated DCs express PDL1 in the absence of CD86 (b). LNs were harvested at day 42 and LN cells were co-cultured in the presence of C19-A3 or proinsulin protein and proliferation and cytokine production were analysed by thymidine incorporation and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). Mean ± standard error of the mean (s.e.m.) proliferation (d), interferon (IFN)-γ (e) and interleukin (IL)-10 (f) production in response to 10 μg/ml C19-A3 or 50 μg/ml proinsulin is shown. Percentages of proliferating CD3+CD4+CD25highforkhead box protein 3(FoxP3+) were measured by flow cytometry in LN cultures at day 42 (g). Statistical significance was determined by one-way analysis of variance (anova) or Student's t-test. *P < 0·05, **P < 0·01. Data are representative of two independent experiments.

In the active treatment groups, C19-A3-VD3-DC therapy down-modulated the proliferative capacity of DLN cultures significantly in response to proinsulin peptide C19-A3 (Fig. 5d). In addition, production of the inflammatory mediator IFN-γ (Fig. 5e) in response to C19-A3 proinsulin peptide was decreased significantly, while levels of the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10 (Fig. 5f) were increased significantly. This modulation of the immune response was antigen-specific as recall responses to OVA, included in the boost, were of equal measure in unpulsed versus C19-A3-pulsed VD3-DC-treated mice (data not shown). Unlike results observed following multi-PIT, we did not detect an increased Ki67+ proliferation of FoxP3+Tregs in mice treated with unpulsed versus C19-A3 pulsed-VD3-DCs (Fig. 5g).

Discussion

An optimal therapeutic approach for the treatment or prevention of type 1 diabetes should include an antigen-specific strategy that specifically targets pathogenic autoreactive T cells without generalized immunosuppression. An important factor for consideration in the design of this approach is the choice of antigen. Proinsulin is considered widely to be a primary autoantigen for initiation of the autoimmune response in type 1 diabetes 3–7. Targeting proinsulin-specific immunological pathways with ASI may therefore offer the opportunity to intervene at a point in the disease that allows recovery of residual β cell function. Previously, we identified a panel of immunodominant proinsulin epitopes, which are naturally processed, presented and targeted by the pathogenic immune response in patients carrying the HLA-DR4 (B1*0401) disease-associated allele 19. To facilitate the application of this panel therapeutically in HLA-DR4 patients, we developed an HLA-DR4 Tg mouse model of proinsulin-targeting autoimmunity. To mimic peptide therapy more closely in humans, we tested proinsulin peptide immunotherapy in the context of pre-existing autoimmunity, tracking T cell proliferation, cytokine production and autoantibodies to whole proinsulin protein and proinsulin peptides. We first established a robust immunization protocol and confirmed disruption of tolerance to proinsulin by demonstrating equivalent proinsulin recall responses to both human and murine versions of peptide epitopes. By tracking these responses ex vivo, we were able to test the tolerogenic potential of human proinsulin peptide-based therapeutic strategies: mono- and multi-PIT and mono-PIT delivered on the surface of VD3 DCs.

The precise mode of action of PIT is unclear, and the lack of appropriate and representative antigen-specific animal models has limited studies investigating peptide dose, route of delivery and whether multiple peptides spanning more than one antigen/autoantigen can enhance the power and breadth of therapeutic effect in the context of autoimmunity. Using our model, we found that multiple peptides of proinsulin are more potent than single peptides in down-modulating pre-existing autoimmunity. We also observed an increased level of Treg proliferation induced by multi-PIT compared to mono-PIT, supporting previous findings that multiple peptides are superior to single agents 22. Therapeutic potency was also affected by the amount of peptide delivered. Lower doses of peptide are thought to favour the induction of CD4+ T cells with regulatory properties, while large doses are associated with clonal deletion and potential side effects such as anaphylactic shock 10,23,24. In terms of peptide dose, we report that a lower dose of 1 μg was as effective as 10 μg, with 1 μg resulting in a significant decrease in serum levels of proinsulin-specific IgG. Frequency of administration was important at maintaining therapeutic effect with weekly more effective than bi-weekly, a finding that may be informative in the design of future clinical trials. Our aim in using a double manipulation (CFA/proinsulin followed by IFA/proinsulin) was to achieve a robust and committed memory response to proinsulin. Evidence that this was indeed achieved in the double- over the single-primed setting (CFA/proinsulin) included our finding of autoantibodies only in the double-primed, and generally higher levels of cytokine release to proinsulin and a greater degree of resistance to PI peptide-induced control in the same model. These findings contrast with Eisenbarth's study 25 showing that antigen/IFA is tolerogenic, but this involved administering insulin-derived peptides (not whole proinsulin) at a very high dose (100 µg) and not against a background of existing induced autoimmunity. It is probable, therefore, that these conditions result in different outcomes. A further question to be clarified in future studies will be the duration of the tolerance effects, which others have shown can be transient 26.

At present, PIT in clinical development focuses on the intradermal route of administration 27. The extent to which this exploits tolerance-promoting pathways in the skin is not known. The dermis is rich in immature tolerogenic dendritic cells capable of binding and presenting peptide antigen to CD4+ T cells in draining lymph nodes. We therefore investigated the therapeutic potential of delivering peptides already bound to the surface of tolerogenic DCs, using the humanized HLA-DR4 Tg mouse model and the immunodominant peptide of proinsulin, C19-A3. C19-A3-pulsed VD3-DCs reduced proinsulin-specific autoimmunity significantly. This treatment also induced a significant peptide-specific IL-10 secretion and reduced IFN-γ production. These results suggest that VD3-modified DCs bearing proinsulin peptide migrate to lymph nodes and deliver potent immune modulatory effects on ongoing proinsulin autoimmunity. Previous studies in the setting of preclinical models of allergy have made similar observations regarding the IL-10 dependency of PIT effects, which also receives support from clinical trials in allergy, type 1 diabetes and other autoimmune diseases 11,22,28.

The differences we observed between mechanistic effects of the different approaches for peptide delivery (modulated VD3-DCs inducing IL-10 and intradermal peptide lowering responses more globally and inducing FoxP3 Tregs) is noteworthy, and potentially informative for translation. The findings suggest that there are distinct, only partially overlapping therapeutic mechanisms. This may enhance our understanding as to how the two therapies might work in man, and provide guidance for future biomarker development following such vaccinations. Potential mechanisms of tolerance induction by ASI include the induction of anergy and the deletion of pathogenic T cells that target the administered sequence 29. Studies in clinical allergy and autoimmunity suggest that the success of PIT depends upon the induction of Treg subsets 30–32. This includes the expansion of pre-existing Tregs or the conversion of naive CD4 T cells. Different groups have reported that VD3-DCs favour the conversion of naive CD4 T cells into FoxP3+ Tregs or IL-10-producing Tr1 cells 33–35. Here we show that treatment with C19-A3 VD3-DCs results in both an enhanced proliferation of Tregs in vivo and a significant peptide-specific IL-10 response. With regard to mono- and multi-PIT, our data demonstrate an association between reduced effector function and enhanced Treg proliferation. Tregs isolated from mice treated with multi-PIT were effective at suppressing proinsulin-specific CD4+ T cell response in vitro, while suppression of polyclonal responses was equivalent to that of control-PIT treated mice, demonstrating the antigen-selective tolerogenic effects of multi-PIT. Induction or expansion of antigen-specific FoxP3+ Tregs by PIT is a hitherto unreported property of this approach, which suggests that there may be the potential for PIT to stimulate the natural regulatory T cell pool, a finding that may underpin the therapeutic effect of PIT in the clinic and aid biomarker identification.

We conclude that this novel HLA-DR4 model of proinsulin autoimmunity has important utility in demonstrating in vivo the immunomodulatory potential of human proinsulin-based immunotherapies, aiding their translation into the clinical setting for restoration of β cell tolerance in patients with type 1 diabetes.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Luciano Vilela from Biomm for his gift of proinsulin protein. This study was supported by funding from the European Union's (EU FP7) Large-Scale Focused Collaborative Research Project on Natural Immunomodulators as Novel Immunotherapies for Type 1 Diabetes (NAIMIT, 241447); the UK Department of Health via the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Biomedical Research Centre Award to Guy's and St Thomas’ National Health Service Foundation Trust in partnership with King's College London and the Dutch Diabetes Research Foundation. MP receives additional funding via the European Commission Seventh Framework Programme (PEVNET and EE-ASI).

Author contributions

V. B. G. and T. N. contributed to the research design, carried out experiments, data analysis and wrote the manuscript. V. Q. P. carried out experiments. J. D. contributed to the study concept. B. O. R. and M. P. contributed to the study concept, research design and wrote and reviewed the manuscript. M. P. is the guarantor of this work and, as such, had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Disclosure

King's College London has a licence agreement with UCB Pharma to develop a peptide-based immunotherapy programme for type 1 diabetes. M. P. currently receives funds for research from UCB Pharma.

References

- Eisenbarth GS, Nayak RC, Rabinowe SL. Type I diabetes as a chronic autoimmune disease. J Diabet Complications. 1988;2:54–8. doi: 10.1016/0891-6632(88)90002-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Herrath M, Peakman M, Roep B. Progress in immune-based therapies for type 1 diabetes. Clin Exp Immunol. 2013;172:186–202. doi: 10.1111/cei.12085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- You S, Chatenoud L. Proinsulin: a unique autoantigen triggering autoimmune diabetes. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:3108–10. doi: 10.1172/JCI30760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishnamurthy B, Dudek NL, McKenzie MD, et al. Responses against islet antigens in NOD mice are prevented by tolerance to proinsulin but not IGRP. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:3258–65. doi: 10.1172/JCI29602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narendran P, Mannering SI, Harrison LC. Proinsulin-a pathogenic autoantigen in type 1 diabetes. Autoimmun Rev. 2003;2:204–10. doi: 10.1016/s1568-9972(03)00009-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mannering SI, Brodnicki TC. Recent insights into CD4+ T-cell specificity and function in type 1 diabetes. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2007;3:557–64. doi: 10.1586/1744666X.3.4.557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L, Nakayama M, Eisenbarth GS. Insulin as an autoantigen in NOD/human diabetes. Curr Opin Immunol. 2008;20:111–8. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2007.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peakman M, von Herrath M. Antigen-specific immunotherapy for type 1 diabetes: maximizing the potential. Diabetes. 2010;59:2087–93. doi: 10.2337/db10-0630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander C, Ying SBKA, Larche M. Fel d 1-derived T cell peptide therapy induces recruitment of CD4+ CD25+; CD4+ interferon-gamma+ T helper type 1 cells to sites of allergen-induced late-phase skin reactions in cat-allergic subjects. Clin Exp Allergy. 2005;35:52–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2005.02143.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wraith DC. Therapeutic peptide vaccines for treatment of autoimmune diseases. Immunol Lett. 2009;122:134–6. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2008.11.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thrower SL, James L, Hall W, et al. Proinsulin peptide immunotherapy in type 1 diabetes: report of a first-in-man Phase I safety study. Clin Exp Immunol. 2009;155:156–65. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2008.03814.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burton BR, Britton GJ, Fang H, et al. Sequential transcriptional changes dictate safe and effective antigen-specific immunotherapy. Nat Commun. 2014;5:4741. doi: 10.1038/ncomms5741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roep BO, Peakman M. Surrogate end points in the design of immunotherapy trials: emerging lessons from type 1 diabetes. Nat Rev Immunol. 2010;10:145–52. doi: 10.1038/nri2705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- She JX. Susceptibility to type I diabetes: HLA-DQ and DR revisited. Immunol Today. 1996;17:323–9. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(96)10014-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pociot F, McDermott MF. Genetics of type 1 diabetes mellitus. Genes Immun. 2002;3:235–49. doi: 10.1038/sj.gene.6363875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleijwegt FS, Laban S, Duinkerken G, et al. Transfer of regulatory properties from tolerogenic to proinflammatory dendritic cells via induced autoreactive regulatory T cells. J Immunol. 2011;187:6357–64. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1101638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unger WW, Laban S, Kleijwegt FS, van der Slik AR, Roep BO. Induction of Treg by monocyte-derived DC modulated by vitamin D3 or dexamethasone: differential role for PD-L1. Eur J Immunol. 2009;39:3147–59. doi: 10.1002/eji.200839103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito K, Bian HJ, Molina M, et al. HLA-DR4-IE chimeric class II transgenic, murine class II-deficient mice are susceptible to experimental allergic encephalomyelitis. J Exp Med. 1996;183:2635–44. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.6.2635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arif S, Tree TI, Astill TP, et al. Autoreactive T cell responses show proinflammatory polarization in diabetes but a regulatory phenotype in health. J Clin Invest. 2004;113:451–63. doi: 10.1172/JCI19585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babaya N, Liu E, Miao D, Li M, Yu L, Eisenbarth GS. Murine high specificity/sensitivity competitive europium insulin autoantibody assay. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2009;11:227–33. doi: 10.1089/dia.2008.0072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira GB, van Etten E, Verstuyf A, et al. 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3 alters murine dendritic cell behaviour in vitro and in vivo. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2011;27:933–41. doi: 10.1002/dmrr.1275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell JD, Buckland KF, McMillan SJ, et al. Peptide immunotherapy in allergic asthma generates IL-10-dependent immunological tolerance associated with linked epitope suppression. J Exp Med. 2009;206:1535–47. doi: 10.1084/jem.20082901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedotti R, Mitchell D, Wedemeyer J, et al. An unexpected version of horror autotoxicus: anaphylactic shock to a self-peptide. Nat Immunol. 2001;2:216–22. doi: 10.1038/85266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu E, Moriyama H, Abiru N, et al. Anti-peptide autoantibodies and fatal anaphylaxis in NOD mice in response to insulin self-peptides B:9-23 and B:13-23. J Clin Invest. 2002;110:1021–7. doi: 10.1172/JCI15488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniel D, Wegmann DR. Protection of nonobese diabetic mice from diabetes by intranasal or subcutaneous administration of insulin peptide B-(9-23) Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:956–60. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.2.956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehl S, Aichele P, Ramseier H, et al. Antigen persistence and time of T-cell tolerization determine the efficacy of tolerization protocols for prevention of skin graft rejection. Nat Med. 1998;4:1015–9. doi: 10.1038/2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel D, Couroux P, Hickey P, et al. Fel d 1-derived peptide antigen desensitization shows a persistent treatment effect 1 year after the start of dosing: a randomized, placebo-controlled study. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;131:103-9–e101-107. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2012.07.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burton BR, Britton GJ, Fang H, et al. Sequential transcriptional changes dictate safe and effective antigen-specific immunotherapy. Nat Commun. 2014;5:4741. doi: 10.1038/ncomms5741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peakman M, Dayan CM. Antigen-specific immunotherapy for autoimmune disease: fighting fire with fire? Immunology. 2001;104:361–6. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.2001.01335.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verhoef A, Alexander C, Kay AB, Larche M. T cell epitope immunotherapy induces a CD4+ T cell population with regulatory activity. PLOS Med. 2005;2:e78. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0020078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wraith DC. Role of interleukin-10 in the induction and function of natural and antigen-induced regulatory T cells. J Autoimmun. 2003;20:273–5. doi: 10.1016/s0896-8411(03)00046-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarzi M, Klunker S, Texier C, et al. Induction of interleukin-10 and suppressor of cytokine signalling-3 gene expression following peptide immunotherapy. Clin Exp Allergy. 2006;36:465–74. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2006.02469.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penna G, Roncari A, Amuchastegui S, et al. Expression of the inhibitory receptor ILT3 on dendritic cells is dispensable for induction of CD4+Foxp3+ regulatory T cells by 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3. Blood. 2005;106:3490–7. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-05-2044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unger WW, Laban S, Kleijwegt FS, van der Slik AR, Roep BO. Induction of Treg by monocyte-derived DC modulated by vitamin D3 or dexamethasone: differential role for PD-L1. Eur J Immunol. 2009;39:3147–59. doi: 10.1002/eji.200839103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ureta G, Osorio F, Morales J, Rosemblatt M, Bono MR, Fierro JA. Generation of dendritic cells with regulatory properties. Transplant Proc. 2007;39:633–7. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2006.12.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]