Abstract

A macrocyclic tetralactam is threaded by a complementary squaraine dye that is flanked by two polyethylene glycol chains to produce a pseudorotaxane complex with favorable near-infrared fluorescence properties. The association thermodynamics and kinetics were measured for a homologous series of squaraines with different N-alkyl substituents at both ends of the dye. The results show that subtle changes in substituent steric size have profound effects on threading kinetics without greatly altering the very high association constant.

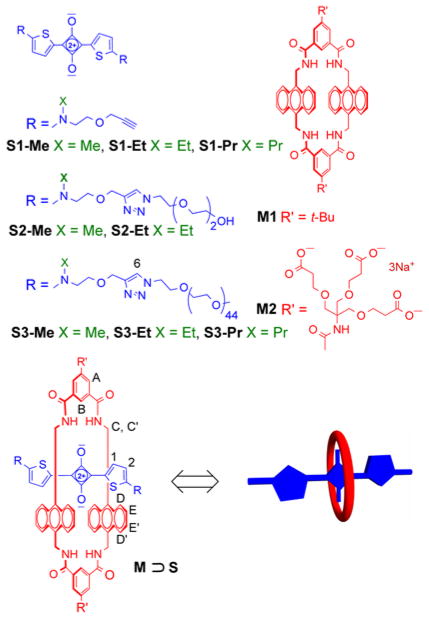

Polymer appended rotaxanes or pseudorotaxanes are functionally attractive molecular architectures with unique structural and dynamic properties.1 Successful rational design of these dynamic systems requires a precise understanding of the structural factors that control the underlying kinetics and thermodynamics.2 We have previously reported that the macrocyclic tetralactam hosts in Scheme 1 can encapsulate highly fluorescent squaraine dyes to give structurally well-defined pseudorotaxane complexes that are well suited for fluorescence imaging of biological samples.3 Squaraine binding studies in different solvents utilized the organic soluble macrocycle M1 or the water soluble version M2: the two structures vary only by the different appendages on the structural periphery. The macrocycles were threaded by the organic soluble bisalkyne squaraine S1-Et, or the water soluble conjugates S2-Et and S3-Et with appended polyethylene glycol (PEG) chains, and very strong binding affinities were recorded due to the complementary fit of squaraine dye inside the macrocycle cavity.3 The two oxygens on the encapsulated squaraine form hydrogens bonds to the four macrocycle NH residues, and there is coplanar stacking of the squaraine aromatic surfaces with the anthracene sidewalls of the macrocycle.4 The macrocycle threading process produced a large ratiometric change in near-infrared optical properties, including turn-on fluorescence, and the pseudorotaxane complexes were stable enough to be visualized during live cell microscopy experiments. The rates of macrocycle threading were remarkably insensitive to the length of the PEG chains attached to the ends of the squaraine dye. For example, extending the length of the PEG chain from ~7 atoms in S2-Et to ~140 atoms in S3-Et only slowed the threading of macrocycle M2 by a factor of three in water. These findings suggest that diffusion of the macrocycle along the PEG chain is not a rate limiting step in the threading process, and this has motivated us to further explore the sensitivity of the squaraine/macrocycle association system to steric effects. Here we report a comparative study of association thermodynamics and kinetics for homologous dye structures with slightly different N-alkyl substituents on the terminal nitrogen atoms at both ends of the squaraine dye (Scheme 2). We find that substituent’s steric size has almost no effect on pseudorotaxane association constant, but there is a large difference in the assembly kinetics. Thus, the N-alkyl substituents act as highly effective “speed bumps” to control the rates of macrocycle threading and dethreading.

Scheme 1.

Chemical structures and atom labels.

Scheme 2.

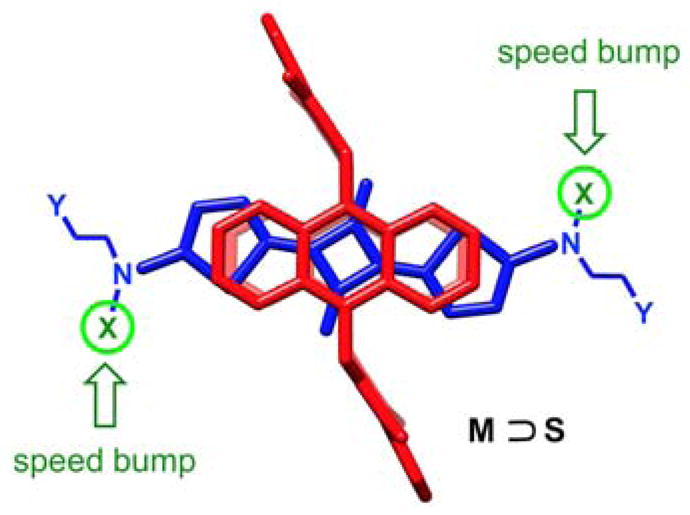

Molecular model of macrocycle/squaraine pseudorotaxane complex (M ⊃ S) showing how the speed bump substituents (X) on the squaraine are located outside the macrocycle cavity. For clarity the peripheral appendages on the surrounding macrocycle and the PEG chains (Y) that flank the squaraine are not shown.

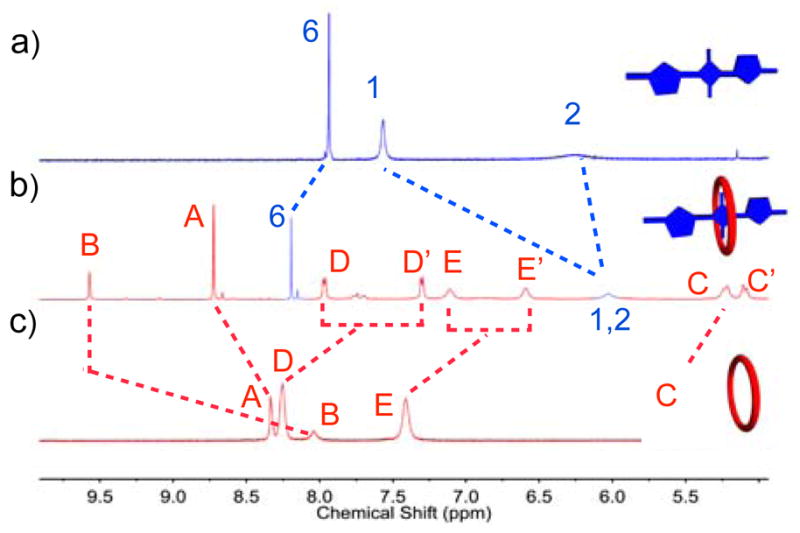

First, we compared the kinetics and thermodynamics for macrocycle threading by the original N-ethyl series of squaraine dyes (i.e., S1-Et, S2-Et, and S3-Et), with a new homologous N-methyl series (S1-Me, S2-Me, and S3-Me). The pseudorotaxane complexes were prepared by mixing separate solutions of M1 or M2 with the different dyes in chloroform, methanol or water, and the self-assembled pseudorotaxane complexes were characterized using the same NMR, fluorescence and UV/Vis absorption methods that were employed previously.3a As expected, macrocycle threading was indicated by several diagnostic and independent spectral features. For example, in Figure 1 are the changes in 1H NMR chemical shifts that occurred when S2-Me was mixed with M2 in D2O to form M2 ⊃ S2-Me (analogous 1H NMR spectra supporting the formation of M1 ⊃ S1-Me in CDCl3 and M2 ⊃ S2-Me in CD3OD are shown in Figures S10 and S11). In agreement with the anisotropic chemical shielding induced by the pseudorotaxane structure, the thiophene proton 1 moved strongly upfield upon complexation, whereas the macrocycle proton B moved strongly downfield. Another common spectral change upon complexation is the 20–30 nm red shift in the squaraine absorption/emission maxima (Table S1). Additional compelling evidence for dye encapsulation by the macrocycle was the observation of efficient energy transfer from an excited anthracene sidewall in the macrocycle (ex: 385 nm) to the encapsulated squaraine dye (em: 704 nm) (Figure S20c).

Figure 1.

Partial 1H NMR spectra (600 MHz, 25 °C, D2O): a) S2-Me, b) 1:1 mixture of M2 and S2-Me to form M2 ⊃ S2-Me, c) M2. Atom labels are provided in Scheme 1.

The association constants listed in Table 1 were determined by conducting fluorescence titration experiments at 20 °C followed by nonlinear fitting of the data to a 1:1 stoichiometry model (the stoichiometry was confirmed by titration experiments using Job’s method, see Figure S20b). Focusing on the most biomedically relevant results in water (entries 5 and 6), the very high association constants for threading of M2 by dyes S2-Me, S2-Et, S3-Me and S3-Et are all within a factor of two.5 The different N-alkyl substituents that flank the encapsulated squaraine dyes are located beyond the macrocycle cavity (Scheme 2), and appear to have very little effect on pseudorotaxane complex stability in water. The thermodynamic factors controlling the association of M2 with S2-Me or S2-Et in water at 27 °C were determined by a combination of fluorescence titration and isothermal titration calorimetry. The values listed in Table S2 show that macrocycle threading to form a very stable pseudorotaxane complex in water is driven by a highly favorable enthalpic change.

Table 1.

Association constants (Ka) and threading rates (kon) for association of squaraine and macrocycle at 20 °C.a,b

| entry | solvent | squaraine | macrocycle | Ka (M−1) | kon (M−1s−1) | squaraine | macrocycle | Ka (M−1) | kon (M−1s−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | CHCl3 | S1-Me | M1 | (7.7 ± 0.8) × 107 | (8.0 ± 0.3) × 104 | S1-Et | M1 | (5.9 ± 1.6) × 105 | (8.6 ± 0.4) |

| 2 | CHCl3 | S3-Me | M1 | (2.5 ± 0.7) × 107 | (3.3 ± 0.7) × 104 | S3-Et | M1 | (2.0 ± 0.5) × 106 | (11.9 ± 0.9) |

| 3 | MeOH | S1-Me | M2 | (2.9 ± 0.1) × 105 | (2.0 ± 0.5) × 106 | S1-Et | M2 | (4.0 ± 0.6) × 105 | (1.2 ± 0.1) × 104 |

| 4 | MeOH | S3-Me | M2 | (1.0 ± 0.1) × 105 | (5.7 ± 0.1) × 105 | S3-Et | M2 | (4.1 ± 0.1) × 105 | (5.1 ± 0.6) × 103 |

| 5 | H2O | S2-Me | M2 | (1.2 ± 0.5) × 109 | (1.1 ± 0.1) × 109 | S2-Et | M2 | (6.0 ± 1.2) × 108 | (1.2 ± 0.1) × 107 |

| 6 | H2O | S3-Me | M2 | (7.5 ± 2.7) × 108 | (7.2 ± 0.3) × 108 | S3-Et | M2 | (1.1 ± 0.4) × 109 | (4.3 ± 0.3) × 106 |

| 7 | FBS | S2-Me | M2 | (2.2 ± 0.2) × 106 | (7.8 ± 0.8) × 105 | S2-Et | M2 | (1.2 ± 0.3) × 107 | (1.7 ± 0.1) × 103 |

| 8 | FBS | S3-Me | M2 | (1.4 ± 0.1) × 106 | (6.3 ± 0.8) × 105 | S3-Et | M2 | (2.2 ± 0.4) × 106 | (2.1 ± 0.2) × 103 |

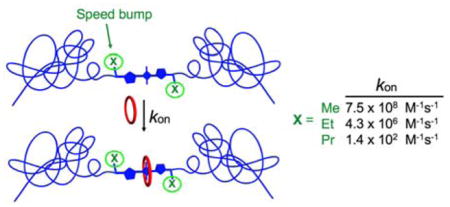

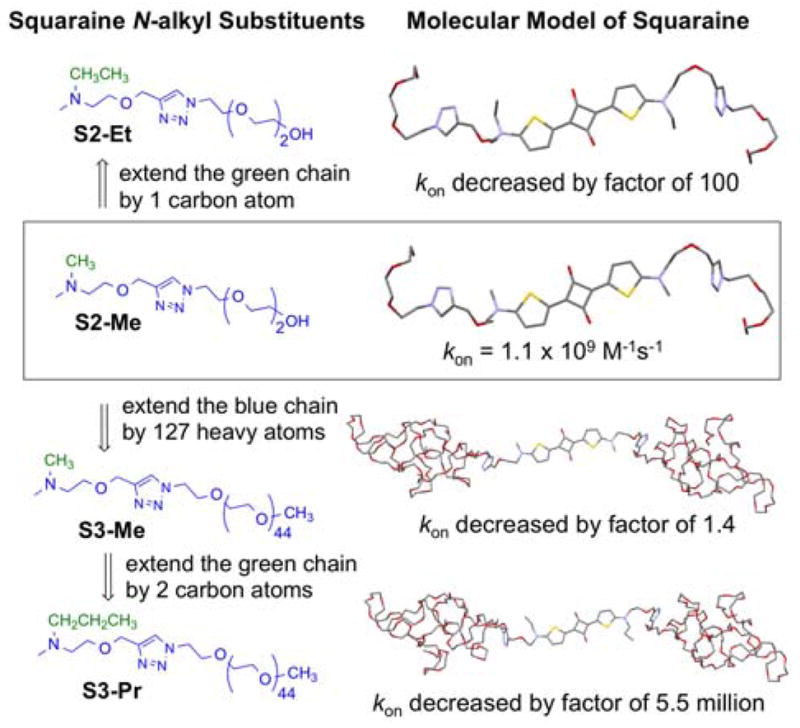

Table 1 also lists the rate constants for macrocycle threading (kon) which were measured by conducting stopped flow experiments and fitting the kinetic profile to a second order reaction model. Consistent with previous observations, the rate constants are highly solvent dependent and increase significantly in the order chloroform < methanol ≪ water.3a There is a remarkable dependence on the steric size of the N-alkyl substituents that flank the squaraine dye. As illustrated in Figure 2, threading of M2 in water by squaraine S2-Me is almost diffusion controlled with kon = 1.1 x 109 M−1s−1. Extending the length of the N-alkyl-PEG chain (colored blue) in S2-Me by adding about 127 atoms to create S3-Me only slowed the threading of M2 by a factor of 1.4 in water, in agreement with the previous trend seen in the N-ethyl series (S2-Et vs S3-Et). But adding one carbon to the N-alkyl substituent (colored green) to create S2-Et dropped kon by a factor of 100.6 This suggests that translocation of the macrocycle over the substituents that are attached to the sp2 hybridized nitrogen atoms on the ends of the squaraine dye is a rate limiting step for the macrocycle threading process. This highly sensitive “speed bump” effect is reminiscent of similar observations by different groups studying steric effects within relatively short rotaxane shuttle or pseudorotaxane threading systems.7 But it has not been reported for systems that thread a macrocycle onto a long polymer chain.2

Figure 2.

Different structural changes in the N-alkyl substituents that flank the squaraine have distinctive effects on the rate constant kon for threading of M2 in water at 20 °C. Squaraine molecular models were optimized using the semiempirical method at PM7 level.

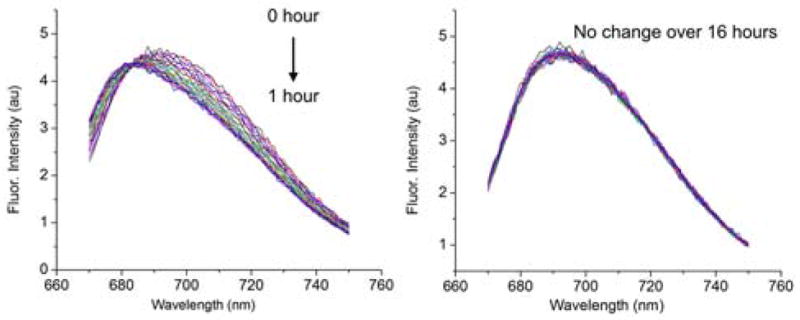

The extremely rapid and high affinity threading of M2 in water by squaraine dyes that are flanked by very long PEG chains is notable,8 and the possibility of eventual biomedical applications prompted us to characterize the process in fetal bovine serum (FBS). Inspection of entries 7 and 8 in Table 1 shows that the macrocycle/squaraine association constant decreases by ~ 102–103 when the solvent is changed from pure water to FBS. Moreover, there is more than a 1000-fold decrease in kon. Serum proteins are known to associate with molecules that have lipophilic surfaces, and presumably the serum proteins compete for the separated molecular partners which decreases kon and Ka. The lower pseudorotaxane stability in serum leads to slow dissociation of a pre-assembled complex. For example, an aliquot of M2 ⊃ S3-Et stock solution (pre-assembled by mixing the two partners at high micromolar concentration in water) was diluted to 500 nM in FBS and observed by fluorescence to partially dissociate over 1 hour (Figure 3).9 We reasoned that the problem of pseudorotaxane dissociation in FBS could be circumvented by adjusting the steric barrier controlling the assembly kinetics.7 We decided to slightly increase the size of the speed bump substituent at each end of the squaraine dye so that it was still small enough to allow efficient macrocycle threading at relatively high concentrations in water, but large enough to slow pseudorotaxane dissociation in FBS. The obvious first choice was an N-propyl substituent and thus we prepared the squaraine dye S3-Pr (Scheme 1) and characterized its association with macrocycle M2. We were pleased to find that S3-Pr and M2 formed a highly stable pseudorotaxane complex in water with Ka = (0.9 ± 0.3) × 108 M−1. The measured value of kon = (1.3 ± 0.2) × 102 M−1s−1 in water at 20 °C was a remarkable 5.5 million times slower than the threading of M2 by S3-Me (Figure 2). Although this is a substantial decrease in the rate of self-assembly, the M2 ⊃ S 3-Pr complex still formed quantitatively within a few minutes when both components were mixed at 500 μM each in water at 20 °C. This aqueous stock solution of M2 ⊃ S3-Pr complex was stable when stored at 4 °C. There was also no measurable dissociation or chemical decomposition when an aliquot of the stock solution was diluted to 500 nM in FBS, as judged by repeated fluorescence scans over 16 hours (Figure 3). Confirmation that the interlocked structure of M2 ⊃ S3-Pr was retained in FBS was gained by irradiating the sample with 385 nm light and observing efficient energy transfer from the anthracene sidewalls of the surrounding macrocycle to the encapsulated squaraine dye which produced strong emission at 695 nm (Figure S30).10 This finding of high chemical and mechanical stability in FBS is very encouraging and suggests that pseudorotaxane complexes with N-propyl “speed bumps” can be rapidly pre-assembled in quantitative yield in water, then diluted into complex biological media and used as stable, high performance, near-infrared fluorescent molecular probes.

Figure 3.

(left) Fluorescence spectra (ex: 650 nm) indicating partial dissociation of M2 ⊃ S3-Et (500 nM) in FBS over 1 h (spectra acquired every 3 min). (right) Fluorescence spectra (ex: 650 nm) indicating no dissociation of M2 ⊃ S3-Pr (500 nM) in FBS over 16 h (spectra acquired every 30 min).

In summary, the results of these studies show that subtle changes in steric size of the N-alkyl substituents at either end of the squaraine structure can produce profound changes in the kinetics of macrocycle threading without greatly altering the mechanical stability of the associated pseudorotaxane complex. This new insight should allow development of macrocycle threading systems with kinetic features that enable specific applications. For example, polymer self-assembly or surface adhesion experiments that require extremely rapid and high-affinity association in water should use PEG conjugated squaraines with N-methyl substituents (such as S3-Me), whereas molecular imaging applications that require a long-lived pre-assembled fluorescent probe in biological media should employ PEG conjugated squaraines with N-propyl substituents (such as S3-Pr) and appropriately modified versions of M2 with appended biomarker targeting ligands. Studies that employ these supramolecular systems for new and interesting applications will be reported in due course.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Financial support for this work was provided by the NSF (CHE1401783).

Footnotes

Notes

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supporting Information: Synthesis and characterization, thermodynamic and kinetics data. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.(a) Van Dongen SFM, Cantekin S, Elemans JAAW, Rowan AE, Nolte RJM. Chem Soc Rev. 2014;43:99. doi: 10.1039/c3cs60178a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Aoki D, Uchida S, Takata T. Polym J. 2014;46:546. [Google Scholar]; (c) Aoki D, Uchida S, Takata T. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2015;54:6670. doi: 10.1002/anie.201500578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) De Bo G, De Winter J, Gerbaux P, Fustin CA. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2011;50:9093. doi: 10.1002/anie.201103716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) van Dongen SFM, Elemans JAAW, Rowan AE, Nolte RJM. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2014;53:11420. doi: 10.1002/anie.201404848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.(a) Deutman ABC, Varghese S, Moalin M, Elemans JAAW, Rowan AE, Nolte RJM. Chem Eur J. 2015;21:360. doi: 10.1002/chem.201403740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Deutman ABC, Cantekin S, Elemans JAAW, Rowan AE, Nolte RJM. J Am Chem Soc. 2014;136:9165. doi: 10.1021/ja5032997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Biedermann F, Elmalem E, Ghosh I, Nau WM, Scherman OA. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2012;51:7859. doi: 10.1002/anie.201202385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Deutman ABC, Monnereau C, Elemans JAAW, Ercolani G, Nolte RJM, Rowan AE. Science. 2008;322:1668. doi: 10.1126/science.1164647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.(a) Peck EM, Liu W, Spence GT, Shaw SK, Davis AP, Destecroix H, Smith BD. J Am Chem Soc. 2015;137:8668. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b03573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Gassensmith JJ, Arunkumar E, Barr L, Baumes JM, DiVittorio KM, Johnson JR, Noll BC, Smith BD. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:15054. doi: 10.1021/ja075567v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.(a) Arunkumar E, Forbes CC, Noll BC, Smith BD. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:3288. doi: 10.1021/ja042404n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Gassensmith JJ, Baumes JM, Smith BD. Chem Commun. 2009:6329. doi: 10.1039/b911064j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Peck EM, Oliver AG, Smith BD. Aust J Chem. 2015;68:1359. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Association constants for pseudorotaxane formation in methanol (entries 3 and 4) are also all quite similar (within a factor of four), whereas the systems in chloroform (entries 1 and 2) show a larger difference in association constants (variation of one hundred). The larger difference in chloroform is likely due to substituent-induced variations in macrocycle/squaraine hydrogen bonding which is a dominant interaction for assembly in the weakly polar organic solvent.

- 6.The threading rate constants (kon) in methanol (entries 3 and 4) also show a 100-fold decrease when the N-alkyl group is changed from N-methyl to N-ethyl, whereas the systems in chloroform (entries 1 and 2) show a much larger difference (decrease of almost 10,000). The larger decrease in chloroform is likely due to a higher activation barrier for passage of the macrocycle over the ends of the squaraine due to stronger hydrogen bonding interactions in the weakly polar organic solvent. There is no kinetic evidence for a major polymer chain entanglement effect in any of the solvents.

- 7.(a) Senler S, Cheng B, Kaifer AE. Org Lett. 2014;16:5834. doi: 10.1021/ol502479k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Dey SK, Coskun A, Fahrenbach AC, Barin G, Basuray AN, Trabolsi A, Botros YY, Stoddart JF. Chem Sci. 2011;2:1046. [Google Scholar]; (c) Carrasco-Ruiz A, Tiburcio J. Org Lett. 2015:10. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.5b00530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Jeppesen JO, Becher J, Stoddart JF. Org Lett. 2002;4:557. doi: 10.1021/ol0171362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Young PG, Hirose K, Tobe Y. J Am Chem Soc. 2014;136:7899. doi: 10.1021/ja412671k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.(a) Verdejo B, Gil-Ramírez G, Ballester P. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:3178. doi: 10.1021/ja900151u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Ferrand Y, Klein E, Barwell NP, Crump MP, Jiménez-Barbero J, Vicent C, Boons GJ, Ingale S, Davis AP. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2009;48:1775. doi: 10.1002/anie.200804905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Ke C, Destecroix H, Crump MP, Davis AP. Nat Chem. 2012;4:718. doi: 10.1038/nchem.1409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Hunter C, Thomas J, Bernad P., Jr Chem Commun. 1998;22:2449. [Google Scholar]

- 9.As a general trend, the rate of complex dissociation (koff) in FBS was observed to be about four times slower than koff in water (calculated from the Ka and kon data in Table 1 and confirmed in some cases by independent measurements) presumably due to association of the complex with the serum proteins (Figure S27).

- 10.In contrast, a control experiment that mixed equimolar amounts of the two partners (M2 and S3-Pr) at 500 nM in FBS for 24 h showed no energy transfer from the anthracene sidewalls to the squaraine, indicating that macrocycle threading had not occurred (Figure S30).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.