Abstract

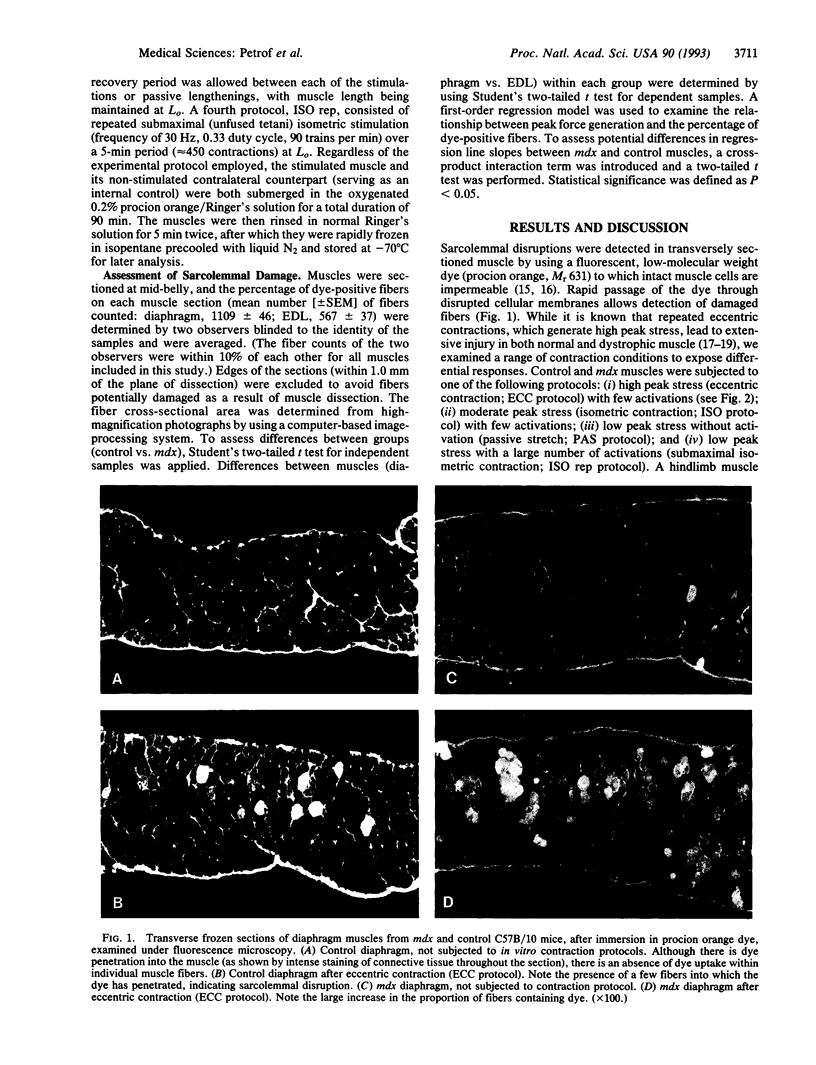

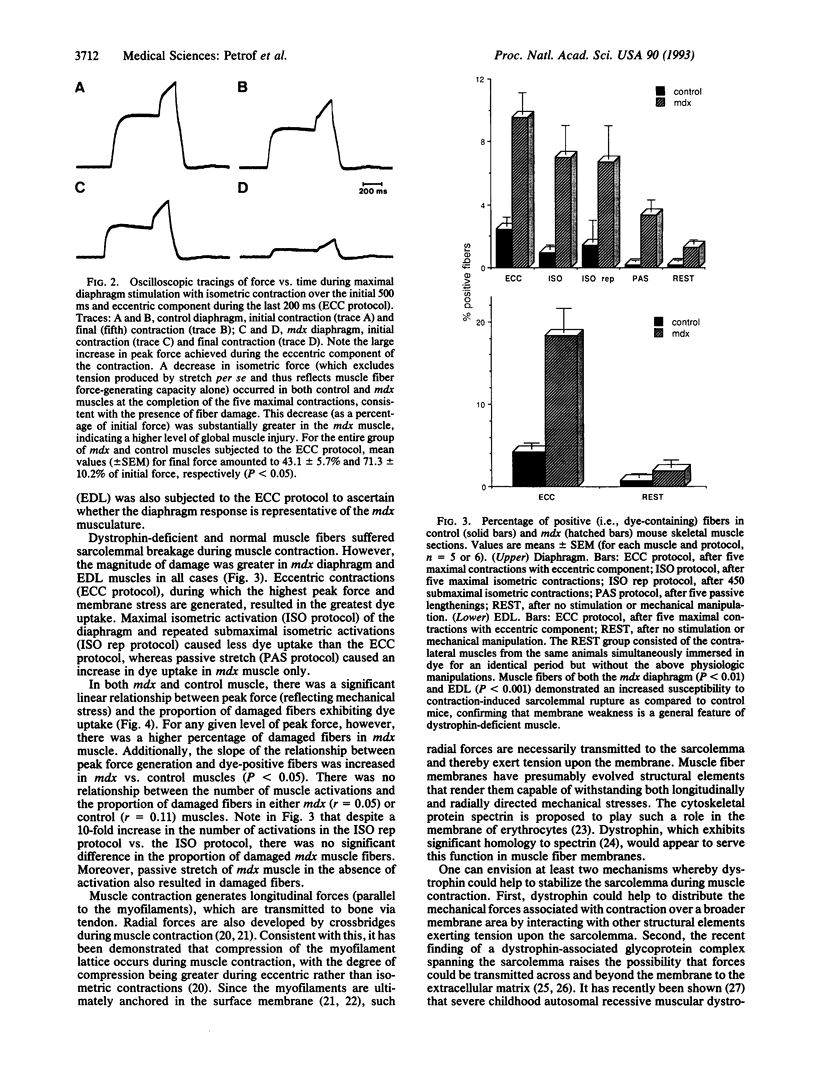

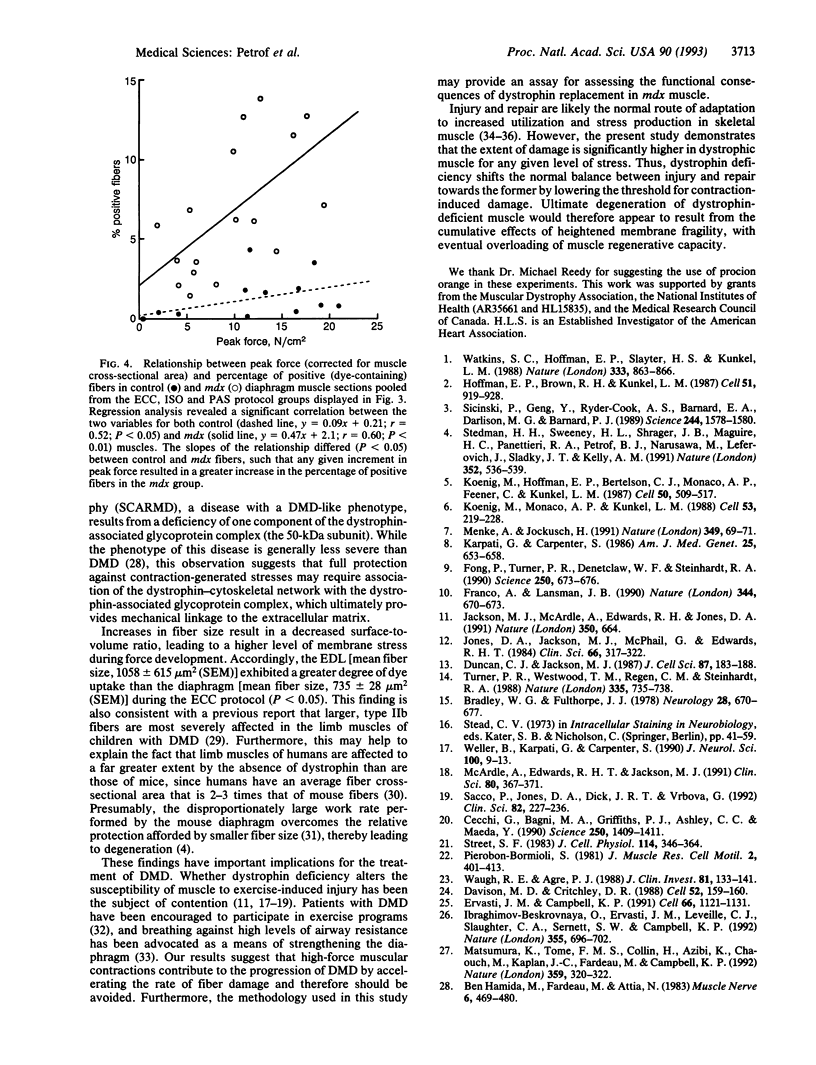

The protein dystrophin, normally found on the cytoplasmic surface of skeletal muscle cell membranes, is absent in patients with Duchenne muscular dystrophy as well as mdx (X-linked muscular dystrophy) mice. Although its primary structure has been determined, the precise functional role of dystrophin remains the subject of speculation. In the present study, we demonstrate that dystrophin-deficient muscle fibers of the mdx mouse exhibit an increased susceptibility to contraction-induced sarcolemmal rupture. The level of sarcolemmal damage is directly correlated with the magnitude of mechanical stress placed upon the membrane during contraction rather than the number of activations of the muscle. These findings strongly support the proposition that the primary function of dystrophin is to provide mechanical reinforcement to the sarcolemma and thereby protect it from the membrane stresses developed during muscle contraction. Furthermore, the methodology used in this study should prove useful in assessing the efficacy of dystrophin gene therapy in the mdx mouse.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Ben Hamida M., Fardeau M., Attia N. Severe childhood muscular dystrophy affecting both sexes and frequent in Tunisia. Muscle Nerve. 1983 Sep;6(7):469–480. doi: 10.1002/mus.880060702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley W. G., Fulthorpe J. J. Studies of sarcolemmal integrity in myopathic muscle. Neurology. 1978 Jul;28(7):670–677. doi: 10.1212/wnl.28.7.670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cecchi G., Bagni M. A., Griffiths P. J., Ashley C. C., Maeda Y. Detection of radial crossbridge force by lattice spacing changes in intact single muscle fibers. Science. 1990 Dec 7;250(4986):1409–1411. doi: 10.1126/science.2255911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davison M. D., Critchley D. R. alpha-Actinins and the DMD protein contain spectrin-like repeats. Cell. 1988 Jan 29;52(2):159–160. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90503-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiMarco A. F., Kelling J. S., DiMarco M. S., Jacobs I., Shields R., Altose M. D. The effects of inspiratory resistive training on respiratory muscle function in patients with muscular dystrophy. Muscle Nerve. 1985 May;8(4):284–290. doi: 10.1002/mus.880080404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan C. J., Jackson M. J. Different mechanisms mediate structural changes and intracellular enzyme efflux following damage to skeletal muscle. J Cell Sci. 1987 Feb;87(Pt 1):183–188. doi: 10.1242/jcs.87.1.183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ervasti J. M., Campbell K. P. Membrane organization of the dystrophin-glycoprotein complex. Cell. 1991 Sep 20;66(6):1121–1131. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90035-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fong P. Y., Turner P. R., Denetclaw W. F., Steinhardt R. A. Increased activity of calcium leak channels in myotubes of Duchenne human and mdx mouse origin. Science. 1990 Nov 2;250(4981):673–676. doi: 10.1126/science.2173137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franco A., Jr, Lansman J. B. Calcium entry through stretch-inactivated ion channels in mdx myotubes. Nature. 1990 Apr 12;344(6267):670–673. doi: 10.1038/344670a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman E. P., Brown R. H., Jr, Kunkel L. M. Dystrophin: the protein product of the Duchenne muscular dystrophy locus. Cell. 1987 Dec 24;51(6):919–928. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90579-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ibraghimov-Beskrovnaya O., Ervasti J. M., Leveille C. J., Slaughter C. A., Sernett S. W., Campbell K. P. Primary structure of dystrophin-associated glycoproteins linking dystrophin to the extracellular matrix. Nature. 1992 Feb 20;355(6362):696–702. doi: 10.1038/355696a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson M. J., McArdle A., Edwards R. H., Jones D. A. Muscle damage in mdx mice. Nature. 1991 Apr 25;350(6320):664–664. doi: 10.1038/350664b0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones D. A., Jackson M. J., McPhail G., Edwards R. H. Experimental mouse muscle damage: the importance of external calcium. Clin Sci (Lond) 1984 Mar;66(3):317–322. doi: 10.1042/cs0660317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones D. A., Newham D. J., Round J. M., Tolfree S. E. Experimental human muscle damage: morphological changes in relation to other indices of damage. J Physiol. 1986 Jun;375:435–448. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1986.sp016126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karpati G., Carpenter S., Prescott S. Small-caliber skeletal muscle fibers do not suffer necrosis in mdx mouse dystrophy. Muscle Nerve. 1988 Aug;11(8):795–803. doi: 10.1002/mus.880110802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karpati G., Carpenter S. Small-caliber skeletal muscle fibers do not suffer deleterious consequences of dystrophic gene expression. Am J Med Genet. 1986 Dec;25(4):653–658. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320250407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasper C. E., White T. P., Maxwell L. C. Running during recovery from hindlimb suspension induces transient muscle injury. J Appl Physiol (1985) 1990 Feb;68(2):533–539. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1990.68.2.533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koenig M., Hoffman E. P., Bertelson C. J., Monaco A. P., Feener C., Kunkel L. M. Complete cloning of the Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) cDNA and preliminary genomic organization of the DMD gene in normal and affected individuals. Cell. 1987 Jul 31;50(3):509–517. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90504-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koenig M., Monaco A. P., Kunkel L. M. The complete sequence of dystrophin predicts a rod-shaped cytoskeletal protein. Cell. 1988 Apr 22;53(2):219–228. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90383-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumura K., Tomé F. M., Collin H., Azibi K., Chaouch M., Kaplan J. C., Fardeau M., Campbell K. P. Deficiency of the 50K dystrophin-associated glycoprotein in severe childhood autosomal recessive muscular dystrophy. Nature. 1992 Sep 24;359(6393):320–322. doi: 10.1038/359320a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McArdle A., Edwards R. H., Jackson M. J. Effects of contractile activity on muscle damage in the dystrophin-deficient mdx mouse. Clin Sci (Lond) 1991 Apr;80(4):367–371. doi: 10.1042/cs0800367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCully K. K., Faulkner J. A. Injury to skeletal muscle fibers of mice following lengthening contractions. J Appl Physiol (1985) 1985 Jul;59(1):119–126. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1985.59.1.119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menke A., Jockusch H. Decreased osmotic stability of dystrophin-less muscle cells from the mdx mouse. Nature. 1991 Jan 3;349(6304):69–71. doi: 10.1038/349069a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizuno M., Secher N. H. Histochemical characteristics of human expiratory and inspiratory intercostal muscles. J Appl Physiol (1985) 1989 Aug;67(2):592–598. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1989.67.2.592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sacco P., Jones D. A., Dick J. R., Vrbová G. Contractile properties and susceptibility to exercise-induced damage of normal and mdx mouse tibialis anterior muscle. Clin Sci (Lond) 1992 Feb;82(2):227–236. doi: 10.1042/cs0820227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sicinski P., Geng Y., Ryder-Cook A. S., Barnard E. A., Darlison M. G., Barnard P. J. The molecular basis of muscular dystrophy in the mdx mouse: a point mutation. Science. 1989 Jun 30;244(4912):1578–1580. doi: 10.1126/science.2662404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stedman H. H., Sweeney H. L., Shrager J. B., Maguire H. C., Panettieri R. A., Petrof B., Narusawa M., Leferovich J. M., Sladky J. T., Kelly A. M. The mdx mouse diaphragm reproduces the degenerative changes of Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Nature. 1991 Aug 8;352(6335):536–539. doi: 10.1038/352536a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Street S. F. Lateral transmission of tension in frog myofibers: a myofibrillar network and transverse cytoskeletal connections are possible transmitters. J Cell Physiol. 1983 Mar;114(3):346–364. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1041140314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner P. R., Westwood T., Regen C. M., Steinhardt R. A. Increased protein degradation results from elevated free calcium levels found in muscle from mdx mice. Nature. 1988 Oct 20;335(6192):735–738. doi: 10.1038/335735a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watkins S. C., Hoffman E. P., Slayter H. S., Kunkel L. M. Immunoelectron microscopic localization of dystrophin in myofibres. Nature. 1988 Jun 30;333(6176):863–866. doi: 10.1038/333863a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waugh R. E., Agre P. Reductions of erythrocyte membrane viscoelastic coefficients reflect spectrin deficiencies in hereditary spherocytosis. J Clin Invest. 1988 Jan;81(1):133–141. doi: 10.1172/JCI113284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webster C., Silberstein L., Hays A. P., Blau H. M. Fast muscle fibers are preferentially affected in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Cell. 1988 Feb 26;52(4):503–513. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90463-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weller B., Karpati G., Carpenter S. Dystrophin-deficient mdx muscle fibers are preferentially vulnerable to necrosis induced by experimental lengthening contractions. J Neurol Sci. 1990 Dec;100(1-2):9–13. doi: 10.1016/0022-510x(90)90005-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]