Abstract

The pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is multifactorial with data suggesting the role of a disturbed interaction between the gut and the intestinal microbiota. A defective mucosal barrier may result in increased intestinal permeability which promotes the exposition to luminal content and triggers an immunological response that promotes intestinal inflammation. IBD patients display several defects in the many specialized components of mucosal barrier, from the mucus layer composition to the adhesion molecules that regulate paracellular permeability. These alterations may represent a primary dysfunction in Crohn's disease, but they may also perpetuate chronic mucosal inflammation in ulcerative colitis. In clinical practice, several studies have documented that changes in intestinal permeability can predict IBD course. Functional tests, such as the sugar absorption tests or the novel imaging technique using confocal laser endomicroscopy, allow an in vivo assessment of gut barrier integrity. Antitumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) therapy reduces mucosal inflammation and restores intestinal permeability in IBD patients. Butyrate, zinc, and some probiotics also ameliorate mucosal barrier dysfunction but their use is still limited and further studies are needed before considering permeability manipulation as a therapeutic target in IBD.

1. Introduction

The gut has a major role in food digestion and absorption as well as in maintaining the general homeostasis. It is estimated that the total bacterial cell count in our body exceeds ten times the total number of human cells, with more than one thousand species hosted in the gastrointestinal tract [1, 2]. The gastrointestinal microbiota, whose genome contains one hundredfold more genes than the entire human genome [3, 4], has important roles in nutrition, energy metabolism, host defense, and immune system development [5]. Indeed the altered microbiota has been linked not only to gastrointestinal diseases but also to the pathogenesis of systemic conditions such as obesity and metabolic syndrome [6, 7]. Therefore, the term “mucosal barrier” seems to properly highlight the pivotal role of the gut in the interaction with microbiota [8]: it is not a static shield but an active apparatus with specialized components. As stated by Bischoff et al. [9] “permeability” is defined as a functional feature of this barrier that on one hand allows the coexistence with bacterial symbionts necessary for our organism and on the other hand prevents luminal penetration of macromolecules and pathogens [10, 11]. Altered intestinal permeability has been documented during several conditions, namely, acute pancreatitis [12], multiple organ failure [13], major surgery [14, 15], and severe trauma [16], and could explain the high prevalence of Gram-negative sepsis and related mortality in critically ill patients [8]. Furthermore, perturbation of the complex mechanism of permeability has been associated with the development of irritable bowel syndrome [17–19] and steatohepatitis (NASH) [20, 21].

The pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is still unclear but in all probability is multifactorial and driven by an exaggerated immune response towards gut microbiome in a genetically susceptible host [22]. Increasing evidence suggests that intestinal permeability may be crucial [23, 24] and some authors even considered IBD as an impaired barrier disease [25].

2. Components of the Intestinal Barrier and Related Dysfunction in Inflammatory Bowel Disease

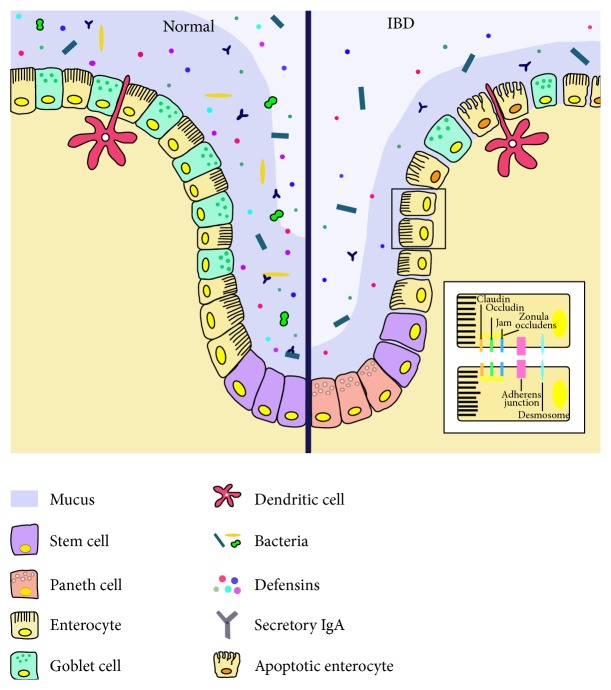

The main component of the mucosal barrier is represented by the intestinal epithelium, which consists of a single layer of different specialized subtypes of cells [9, 22]: enterocytes, goblet cells, Paneth cells, and enteroendocrine cells but also immunity cells such as intraepithelial lymphocytes and dendritic cells (Figure 1). The mechanical cohesion of these cells and the regulation of paracellular permeability of ions and small molecules are ensured by three types of junctional complexes, namely, tight junctions (TJs), adherence junctions, and desmosomes [24, 26, 27].

Figure 1.

Components of the mucosal barrier in healthy gut (left) and inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) (right). For explanations see text. The basic structure of tight junctions and other junctional complexes are shown in the bottom-right box. JAM: junctional adhesion molecules.

IBD patients display increased paracellular permeability [28] with TJs abnormalities documented in several studies [29, 30]. These are complex multiproteins structures with an extracellular portion, a transmembrane domain and an intracellular connection with cytoskeleton (Figure 1). A decreased expression and redistribution of their constituents, including occludins, claudins, and junctional adhesion molecules (JAM), have all been documented in IBD [31–34] and a recent experimental mouse model found that deletion of claudin-7 initiates colonic inflammation [35]. Furthermore, tumour necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), one of the main effectors of IBD inflammation, may modulate the transcription of TJs proteins while its antagonists (anti-TNF-α) can ameliorate intestinal permeability [36, 37]. However, TNF-α leads to altered permeability also, inducing apoptosis of enterocytes, increasing their rate of shedding, and hindering the redistribution of TJs that should seal the gaps left [22, 38–41].

Goblet cells are specialized in the secretion of mucus which covers the surface of intestinal epithelium. Mucus is composed of proteins, carbohydrates, lipids, and a high degree of water but displays also antimicrobial properties thanks to antimicrobial peptides, mainly defensins produced by Paneth cells, and secretory IgA [24]. Ulcerative Colitis (UC) patients show a reduced number of goblet cells [42], a reduced thickness of the mucus layer [43, 44], and an altered mucus composition in terms of mucins, phosphatidylcholine, and glycosylation [45–48]. Moreover, altered Paneth cell distribution and function have been documented in IBD: these cells are normally restricted to the small intestines, within the crypts of Lieberkühn, but in IBD metaplastic Paneth cells may be detected in colonic mucosa, with subsequent secretion of defensins also in the large intestine [24, 49, 50]. However, the role of Paneth cells may be different in the two disease phenotypes since the expression of defensins is inducible by colonic inflammation in UC but is reduced in patients with colonic Crohn's disease (CD) [51]. Indeed, the diminished Paneth cell antimicrobial function might be a primary pathogenic factor in CD, particularly ileal CD [24, 43, 52, 53], while the increased secretion of defensins in UC may be a physiological response to mucosal damage.

3. Etiology of Permeability Dysfunction in Inflammatory Bowel Disease

Whether mucosal barrier impairment is a consequence of the inflammatory response or a primary defect that prompts mucosal inflammation is still under debate [54]. However, several studies suggest that altered intestinal permeability may be an early event in CD pathogenesis. First of all an augmented paracellular permeability has been found also in patients with quiescent IBD and correlated with intestinal symptoms even when endoscopic activity was absent [55]. Furthermore, an ex vivo study using Ussing chambers on colonic biopsies from CD patients [31] demonstrated a spatially uniform increase in transepithelial conductivity despite the presence of minimal mucosal erosions. This finding was attributed to the downregulation of TJs proteins. Finally, animal models of CD, namely, IL-10 knockout mice and SAMP1/YitFc mice, confirmed that increased permeability can be detected before the onset of mucosal inflammation [54].

On the other hand, genes involved in intestinal barrier homeostasis have been associated with IBD susceptibility [56] suggesting a genetic predisposition that is further supported by the observation that up to 40% of first-degree relatives of CD patients display an altered small intestinal permeability [57–62], with significant association with familial CD and NOD2/CARD15 variants [63, 64]. This gene, which is involved in bacterial recognition, modulates both innate and adaptive immune responses and is the main susceptibility locus for CD development [55]. Other studies have not found a correlation between permeability and genetic polymorphisms [60, 62, 65] but it is noteworthy that they have mostly involved sporadic CD cases. However, environmental factors too are main contributors in determining mucosal permeability since permeability is increased even in a proportion of CD spouses [61]. Moreover, a recent study highlighted the importance of age and smoking status rather than genotype in relatives [65]. Finally, to date there is only one reported case of CD development predicted by an abnormal permeability test in a healthy relative [66].

Independently from being genetically determined or caused by environmental factors, permeability impairment leads to the disruption of the physiological balance between mucosal barrier and luminal challenge [25] which cannot be adequately counteracted by innate immunity of IBD patients, which on the contrary responds with an aberrant immune activation [67]. As a matter of fact several defects in bacterial recognition and processing have been documented in CD patients carrying particular genetic polymorphisms, chiefly of pattern-recognition receptors such as NOD2/CARD15 [68, 69] and genes involved in autophagy like ATG16L1 and IRGM [70–72]. In intestinal mucosa, the lack of feedback between mutated NOD2/CARD15 expression and gut luminal microbiota can lead to the breakdown of tolerance [73]. Interestingly, a recent study by Nighot et al. demonstrated that autophagy is also involved in the regulation of TJs by degradation of a pore-forming claudin [74], linking autophagy to permeability.

Finally, intestinal microbiota per se is altered in IBD, particularly in its relative composition and diversity. This may represent a consequence of chronic mucosal inflammation but the influence of host genotype in shaping microbial community cannot be overlooked in CD [75] and NOD2/CARD15 genotype has been shown to influence the composition of gut microbiota in humans [76]. This dysbiosis may further aggravate permeability dysfunction by the loss of the symbiotic relationship between the microbiota and the mucosal barrier integrity [77].

4. Clinical Evaluation of Permeability in Inflammatory Bowel Disease

Permeability impairment may be early involved during the development of CD inflammation. Indeed, some of the known risk factors for disease relapse may induce inflammation through the increased mucosal permeability: this is a well-known mechanism for nonsteroids anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) [78] and recent evidence demonstrated that even stress acts in a similar manner through the release of corticotropin-releasing factors [79]. Furthermore, an impaired small intestinal permeability can predict the risk of CD relapse [80, 81] and patients with altered lactulose/mannitol test (L/M test) have 8-fold risk of relapse even if asymptomatic and with normal biochemical indices [82].

L/M test evaluates small intestinal permeability by measuring the urinary excretion after oral administration of these sugars. Lactulose is a large size oligosaccharide that usually does not have paracellular transport and can be adsorbed only in case of leakiness of intercellular junctions; mannitol is a smaller molecule that can freely cross the intestinal epithelium. Both the probes are equally affected by gastrointestinal dilution, motility, bacterial degradation, and renal function; thus, the ratio allows for correcting possible confounding factors [9, 82]. L/M test is used in clinical practice thanks to its noninvasiveness, its high sensitivity in detecting active IBD, and its ability to discriminate functional versus organic gastrointestinal disease [23, 83–87]. An altered L/M test has been reported in up to nearly 50% of CD patients [62]. Other sugars are routinely used to evaluate the upper intestinal tract, such as sucrose which is degraded by duodenal sucrase, thus reflecting the permeability of the stomach and the proximal duodenum [9, 88]. Therefore, multisugar tests have been developed, with the recent addition of sucralose, which is scarcely absorbed throughout the human intestine and thus allows a functional assessment of the whole intestinal tract, widening the possible application to UC [89].

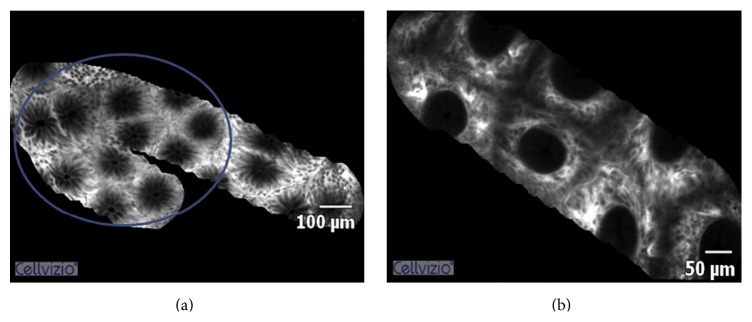

Other functional tests, such as 51Cr-EDTA [90–92] or the Ussing chambers [9], have demonstrated good accuracy but their invasiveness and the complex detection methods preclude their use in humans. Whereas promising results are shown by novel imaging techniques, particularly confocal laser endomicroscopy. this endoscopic technique allows an in vivo evaluation of the epithelial lining and vasculature with the use of intravenous fluorescein as a molecular contrast agent, which usually does not have paracellular transport [93]. Confocal laser endomicroscopy is now widely used in diagnosis and classification of gastrointestinal tumours [94–97] but it has also been applied in nonneoplastic conditions such as celiac disease [98], collagenous colitis [99], and irritable bowel syndrome [100]. The up to one thousandfold magnification permits detection of cellular and subcellular changes such as cell shedding [101], making it a powerful technique for the imaging of any defects in mucosal barrier in IBD. Confocal laser endomicroscopy demonstrated increased density of mucosal gaps after cell shedding in small bowel of CD patients [102] but also in macroscopically normal duodenum in both CD and UC [103]. Far from being just speculative findings these alterations may represent a subclinical impairment of intestinal permeability possibly predicting subsequent clinical relapse [104]. Recently confocal laser endomicroscopy has been applied in UC patients demonstrating that the occurrence of crypt architectural abnormalities can predict disease relapse in patients with apparent endoscopic remission (Figure 2) [105].

Figure 2.

Confocal laser endomicroscopy images from a healthy subject (a) and an Ulcerative Colitis (UC) patient with inactive disease (b). UC patients display increased crypt diameter, intercryptic distance, and perivascular fluorescence. Courtesy of Dr. A. Buda and with permission of Journal of Crohn's and Colitis [105]; © inclusion under a Creative Commons license or any other open-access license allowing onward reuse is prohibited.

5. Permeability-Oriented Therapies

Agents routinely used in the therapeutic armamentarium of IBD may induce and maintain mucosal remission not only for their immunomodulating effect, but also through the restoration of epithelial integrity and permeability, as has been demonstrated for anti-TNF-α drugs in CD [37, 106]. Since similar effects have been obtained using elemental diets in CD [107, 108], increasing interest relies on dietary approaches with the use of immunomodulatory nutrients and probiotics.

Western diet with its high content of fat and refined sugars is a risk factor for the development of CD [109] probably inducing a low-grade inflammation via gut dysbiosis and increased intestinal permeability [110–112]. Furthermore, there is increasing concern about the role of industrial food additives as promoters of immune-related diseases. A recent review showed the ability of additives to increase intestinal permeability by interfering with the TJs, promoting the passage of immunogenic antigens [113]. On the contrary, certain fatty acids (propionate, acetate, butyrate, omega-3, and conjugated linoleic acid), amino acids (glutamine, arginine, tryptophan, and citrulline), and oligoelements, essential for intestinal surface integrity, when supplemented to experimental models of gut diseases, can reduce inflammation and restore mucosal permeability [114]. However, their therapeutic efficacy, particularly in IBD, remains debatable: butyrate, zinc, and probiotics have the strongest evidence in this regard.

Butyrate is a short chain fatty acid produced by intestinal microbial fermentation of dietary fibres [115] which in experimental models stimulates mucus production and expression of TJs in vitro but a wider range of action is expected [116–120]. It is so crucial for general homeostasis of enterocytes that its deficiency, measured as faecal concentrations, has been taken as an indirect indicator of altered barrier function [9, 121, 122]. In clinical practice topical butyrate had proved efficacy in refractory distal UC [123].

Other fatty acids with similar properties have also been proposed as an adjuvant therapy in IBD, namely, omega-3 and phosphatidylcholine [124–126], but their use in clinical practice is still limited.

Zinc is a trace element essential for cell turnover and repair systems. Inflammatory conditions and malnutrition are known risk factors for zinc deficiency and several works proved the efficacy of its supplementation during acute diarrhoea and experimental colitis [127–129]. We have shown that oral zinc therapy can restore intestinal permeability in CD patients probably through its ability to modulate TJs both in the small and the large bowels [130, 131].

The rationale for the use of probiotics in IBD is the aforementioned dysbiosis that characterizes these diseases. Several trials have tested the efficacy of different species of probiotics in IBD, with conflicting results. To date the ones with proven efficacy are Escherichia coli Nissle 1917, Bifidobacterium, Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG, or the multispecies VSL#3 which contains eight different probiotics [132]. Yet their use is still limited to UC and often aimed at maintaining remission rather than treating active disease, as highlighted by the meta analysis by Jonkers et al. [133]. The mechanisms of their effect in UC have not been fully understood but probably, along with direct anti-inflammatory effects, they may strengthen mucosal barrier [134, 135] and reduce intestinal permeability once again upregulating TJs proteins [136, 137]. Even the beneficial effect of probiotics in pouchitis seems to be related to the enhancement of mucosal barrier function [138]. Another potential mechanism of action is the restoration of butyrate-producing bacteria: UC patients have reduced bacterial species like Faecalibacterium prausnitzii [133, 139] and supplementation with butyrate-producing species or probiotics along with preformed butyrate showed efficacy in experimental models [140, 141].

Finally, vitamin D is worth a mention because it is involved in maintaining intestinal barrier function [113] and polymorphisms of its receptor have been associated with the development of IBD [142, 143]. While the expression of vitamin D receptor on intestinal epithelium inhibits inflammation-induced apoptosis [144], its deletion leads to defective autophagy that promotes experimental colitis [145]. However, further data and clinical trials are needed to rationalize vitamin D use in IBD management [146].

6. Conclusions

The impairment of intestinal barrier function is one of the key events in the pathogenesis of IBD. Whether it precedes and predisposes disease development is still under investigation, especially in CD, but surely it perpetuates and enhances chronic mucosal inflammation by increasing paracellular transport of luminal pathogens.

Novel functional and imaging techniques allow us to assess mucosal permeability in vivo and help identifying patients at risk of relapse guiding therapeutic management.

Manipulation of intestinal permeability is an intriguing therapeutic approach but more studies on efficacy and safety are warranted before nutritional immune-modulators can be used in clinical practice.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Luisa Michielan for her graphical assistance. We also thank Dr. Andrea Buda and Oxford University Press-Journal of Crohn and Colitis for kind permission to use original material [105] as view only, which is not an open-access license and any further use requires permission of Oxford University Press.

Conflict of Interests

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interests regarding the publication of this paper.

References

- 1.Savage D. C. Microbial ecology of the gastrointestinal tract. Annual Review of Microbiology. 1977;31:107–133. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.31.100177.000543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Orel R., Trop T. K. Intestinal microbiota, probiotics and prebiotics in inflammatory bowel disease. World Journal of Gastroenterology. 2014;20(33):11505–11524. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i33.11505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stephani J., Radulovic K., Niess J. H. Gut microbiota, probiotics and inflammatory bowel disease. Archivum Immunologiae et Therapiae Experimentalis. 2011;59(3):161–177. doi: 10.1007/s00005-011-0122-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tsai F., Coyle W. J. The microbiome and obesity: is obesity linked to our gut flora? Current Gastroenterology Reports. 2009;11(4):307–313. doi: 10.1007/s11894-009-0045-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Borody T. J., Paramsothy S., Agrawal G. Fecal microbiota transplantation: indications, methods, evidence, and future directions. Current Gastroenterology Reports. 2013;15(8, article 337) doi: 10.1007/s11894-013-0337-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Escobedo G., López-Ortiz E., Torres-Castro I. Gut microbiota as a key player in triggering obesity, systemic inflammation and insulin resistance. Revista de Investigación Clínica. 2014;66(5):450–459. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Festi D., Schiumerini R., Eusebi L. H., Marasco G., Taddia M., Colecchia A. Gut microbiota and metabolic syndrome. World Journal of Gastroenterology. 2014;20(43):16079–16094. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i43.16079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cummings J. H., Antoine J. M., Azpiroz F., et al. PASSCLAIM1—gut health and immunity. European Journal of Nutrition. 2004;43(supplement 2):ii118–ii173. doi: 10.1007/s00394-004-1205-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bischoff S. C., Barbara G., Buurman W., et al. Intestinal permeability—a new target for disease prevention and therapy. BMC Gastroenterology. 2014;14, article 189 doi: 10.1186/s12876-014-0189-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hooper L. V., Littman D. R., Macpherson A. J. Interactions between the microbiota and the immune system. Science. 2012;336(6086):1268–1273. doi: 10.1126/science.1223490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Maynard C. L., Elson C. O., Hatton R. D., Weaver C. T. Reciprocal interactions of the intestinal microbiota and immune system. Nature. 2012;489(7415):231–241. doi: 10.1038/nature11551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fishman J. E., Levy G., Alli V., Zheng X., Mole D. J., Deitch E. A. The intestinal mucus layer is a critical component of the gut barrier that is damaged during acute pancreatitis. Shock. 2014;42(3):264–70. doi: 10.1097/shk.0000000000000209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Swank G. M., Deitch E. A. Role of the gut in multiple organ failure: bacterial translocation and permeability changes. World Journal of Surgery. 1996;20(4):411–417. doi: 10.1007/s002689900065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Derikx J. P. M., van Waardenburg D. A., Thuijls G., et al. New insight in loss of gut barrier during major non-abdominal surgery. PLoS ONE. 2008;3(12) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003954.e3954 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Al-Bahrani A. Z., Darwish A., Hamza N., et al. Gut barrier dysfunction in critically ill surgical patients with abdominal compartment syndrome. Pancreas. 2010;39(7):1064–1069. doi: 10.1097/mpa.0b013e3181da8d51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.de Haan J. J., Lubbers T., Derikx J. P., et al. Rapid development of intestinal cell damage following severe trauma: a prospective observational cohort study. Critical Care. 2009;13(3, article R86) doi: 10.1186/cc7910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Camilleri M., Lasch K., Zhou W. Irritable bowel syndrome: methods, mechanisms, and pathophysiology: the confluence of increased permeability, inflammation, and pain in irritable bowel syndrome. American Journal of Physiology—Gastrointestinal and Liver Physiology. 2012;303(7):G775–G785. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00155.2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Martínez C., Lobo B., Pigrau M., et al. Diarrhoea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome: an organic disorder with structural abnormalities in the jejunal epithelial barrier. Gut. 2013;62(8):1160–1168. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2012-302093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mujagic Z., Ludidi S., Keszthelyi D., et al. Small intestinal permeability is increased in diarrhoea predominant IBS, while alterations in gastroduodenal permeability in all IBS subtypes are largely attributable to confounders. Alimentary Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 2014;40(3):288–297. doi: 10.1111/apt.12829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Scarpellini E., Lupo M., Iegri C., Gasbarrini A., De Santis A., Tack J. Intestinal permeability in non-alcoholic fatty LIVER disease: the gut-liver axis. Reviews on Recent Clinical Trials. 2014;9(3):141–147. doi: 10.2174/1574887109666141216104334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ray K. NAFLD: leaky guts: intestinal permeability and NASH. Nature Reviews Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 2015;12(3, article 123) doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2015.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Coskun M. Intestinal epithelium in inflammatory bowel disease. Frontiers in Medicine. 2014;1, article 24 doi: 10.3389/fmed.2014.00024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mankertz J., Schulzke J.-D. Altered permeability in inflammatory bowel disease: pathophysiology and clinical implications. Current Opinion in Gastroenterology. 2007;23(4):379–383. doi: 10.1097/mog.0b013e32816aa392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Antoni L., Nuding S., Wehkamp J., Stange E. F. Intestinal barrier in inflammatory bowel disease. World Journal of Gastroenterology. 2014;20(5):1165–1179. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i5.1165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jäger S., Stange E. F., Wehkamp J. Inflammatory bowel disease: an impaired barrier disease. Langenbeck's Archives of Surgery. 2013;398(1):1–12. doi: 10.1007/s00423-012-1030-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Groschwitz K. R., Hogan S. P. Intestinal barrier function: molecular regulation and disease pathogenesis. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 2009;124(1):3–22. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2009.05.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Roda G., Sartini A., Zambon E., et al. Intestinal epithelial cells in inflammatory bowel diseases. World Journal of Gastroenterology. 2010;16(34):4264–4271. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v16.i34.4264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Söderholm J. D., Peterson K. H., Olaison G., et al. Epithelial permeability to proteins in the noninflamed ileum of Crohn's disease? Gastroenterology. 1999;117(1):65–72. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(99)70551-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Salim S. Y., Söderholm J. D. Importance of disrupted intestinal barrier in inflammatory bowel diseases. Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. 2011;17(1):362–381. doi: 10.1002/ibd.21403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee S. H. Intestinal permeability regulation by tight junction: implication on inflammatory bowel diseases. Intestinal Research. 2015;13(1):11–18. doi: 10.5217/ir.2015.13.1.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zeissig S., Bürgel N., Günzel D., et al. Changes in expression and distribution of claudin 2, 5 and 8 lead to discontinuous tight junctions and barrier dysfunction in active Crohn's disease. Gut. 2007;56(1):61–72. doi: 10.1136/gut.2006.094375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vetrano S., Rescigno M., Cera M. R., et al. Unique role of junctional adhesion molecule-a in maintaining mucosal homeostasis in inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 2008;135(1):173–184. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Edelblum K. L., Turner J. R. The tight junction in inflammatory disease: communication breakdown. Current Opinion in Pharmacology. 2009;9(6):715–720. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2009.06.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Krug S. M., Schulzke J. D., Fromm M. Tight junction, selective permeability, and related diseases. Seminars in Cell and Developmental Biology. 2014;36:166–176. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2014.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tanaka H., Takechi M., Kiyonari H., Shioi G., Tamura A., Tsukita S. Intestinal deletion of Claudin-7 enhances paracellular organic solute flux and initiates colonic inflammation in mice. Gut. 2015;64(10):1529–1538. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2014-308419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schmitz H., Fromm M., Bentzel C. J., et al. Tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNFα) regulates the epithelial barrier in the human intestinal cell line HT-29/B6. Journal of Cell Science. 1999;112(part 1):137–146. doi: 10.1242/jcs.112.1.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Suenaert P., Bulteel V., Lemmens L., et al. Anti-tumor necrosis factor treatment restores the gut barrier in Crohn's disease. American Journal of Gastroenterology. 2002;97(8):2000–2004. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9270(02)04271-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Marini M., Bamias G., Rivera-Nieves J., et al. TNF-alpha neutralization ameliorates the severity of murine Crohn's-like ileitis by abrogation of intestinal epithelial cell apoptosis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2003;100(14):8366–8371. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1432897100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Heller F., Florian P., Bojarski C., et al. Interleukin-13 is the key effector Th2 cytokine in ulcerative colitis that affects epithelial tight junctions, apoptosis, and cell restitution. Gastroenterology. 2005;129(2):550–564. doi: 10.1016/j.gastro.2005.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Su L., Nalle S. C., Shen L., et al. TNFR2 activates mlck-dependent tight junction dysregulation to cause apoptosis-mediated barrier loss and experimental colitis. Gastroenterology. 2013;145(2):407–415. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Watson A. J. M., Hughes K. R. TNF-α-induced intestinal epithelial cell shedding: implications for intestinal barrier function. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2012;1258(1):1–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2012.06523.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pullan R. D., Thomas G. A. O., Rhodes M., et al. Thickness of adherent mucus gel on colonic mucosa in humans and its relevance to colitis. Gut. 1994;35(3):353–359. doi: 10.1136/gut.35.3.353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gersemann M., Wehkamp J., Stange E. F. Innate immune dysfunction in inflammatory bowel disease. Journal of Internal Medicine. 2012;271(5):421–428. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2012.02515.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chen S.-J., Liu X.-W., Liu J.-P., Yang X.-Y., Lu F.-G. Ulcerative colitis as a polymicrobial infection characterized by sustained broken mucus barrier. World Journal of Gastroenterology. 2014;20(28):9468–9475. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i28.9468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Braun A., Treede I., Gotthardt D., et al. Alterations of phospholipid concentration and species composition of the intestinal mucus barrier in ulcerative colitis: a clue to pathogenesis. Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. 2009;15(11):1705–1720. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Larsson J. M. H., Karlsson H., Crespo J. G., et al. Altered O-glycosylation profile of MUC2 mucin occurs in active ulcerative colitis and is associated with increased inflammation. Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. 2011;17(11):2299–2307. doi: 10.1002/ibd.21625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Clamp J. R., Fraser G., Read A. E. Study of the carbohydrate content of mucus glycoproteins from normal and diseased colons. Clinical Science. 1981;61(2):229–234. doi: 10.1042/cs0610229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Raouf A. H., Tsai H. H., Parker N., Hoffman J., Walker R. J., Rhodes J. M. Sulphation of colonic and rectal mucin in inflammatory bowel disease: reduced sulphation of rectal mucus in ulcerative colitis. Clinical Science. 1992;83(5):623–626. doi: 10.1042/cs0830623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Müller C. A., Autenrieth I. B., Peschel A. Innate defenses of the intestinal epithelial barrier. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences. 2005;62(12):1297–1307. doi: 10.1007/s00018-005-5034-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cunliffe R. N., Rose F. R. A. J., Keyte J., Abberley L., Chan W. C., Mahida Y. R. Human defensin 5 is stored in precursor form in normal Paneth cells and is expressed by some villous epithelial cells and by metaplastic Paneth cells in the colon in inflammatory bowel disease. Gut. 2001;48(2):176–185. doi: 10.1136/gut.48.2.176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wehkamp J., Harder J., Weichenthal M., et al. Inducible and constitutive beta-defensins are differentially expressed in Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis. Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. 2003;9(4):215–223. doi: 10.1097/00054725-200307000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Koslowski M. J., Beisner J., Stange E. F., Wehkamp J. Innate antimicrobial host defense in small intestinal Crohn's disease. International Journal of Medical Microbiology. 2010;300(1):34–40. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmm.2009.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gersemann M., Wehkamp J., Fellermann K., Stange E. F. Crohn's disease-defect in innate defence. World Journal of Gastroenterology. 2008;14(36):5499–5503. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.5499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Teshima C. W., Dieleman L. A., Meddings J. B. Abnormal intestinal permeability in Crohn's disease pathogenesis. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2012;1258(1):159–165. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2012.06612.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Vivinus-Nébot M., Frin-Mathy G., Bzioueche H., et al. Functional bowel symptoms in quiescent inflammatory bowel diseases: role of epithelial barrier disruption and low-grade inflammation. Gut. 2014;63(5):744–752. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2012-304066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Khor B., Gardet A., Xavier R. J. Genetics and pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel disease. Nature. 2011;474(7351):307–317. doi: 10.1038/nature10209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hollander D., Vadheim C. M., Brettholz E., Petersen G. M., Delahunty T., Rotter J. I. Increased intestinal permeability in patients with Crohn's disease and their relatives. A possible etiologic factor. Annals of Internal Medicine. 1986;105(6):883–885. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-105-6-883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.May G. R., Sutherland L. R., Meddings J. B. Is small intestinal permeability really increased in relatives of patients with Crohn's disease? Gastroenterology. 1993;104(6):1627–1632. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(93)90638-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Munkholm P., Langholz E., Hollander D., et al. Intestinal permeability in patients with Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis and their first degree relatives. Gut. 1994;35(1):68–72. doi: 10.1136/gut.35.1.68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Peeters M., Geypens B., Claus D., et al. Clustering of increased small intestinal permeability in families with Crohn's disease. Gastroenterology. 1997;113(3):802–807. doi: 10.1016/S0016-5085(97)70174-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Russell R. K., Satsangi J. IBD: a family affair. Best Practice and Research: Clinical Gastroenterology. 2004;18(3):525–539. doi: 10.1016/j.bpg.2003.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Fries W., Renda M. C., Lo Presti M. A., et al. Intestinal permeability and genetic determinants in patients, first-degree relatives, and controls in a high-incidence area of Crohn's disease in Southern Italy. The American Journal of Gastroenterology. 2005;100(12):2730–2736. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.00325.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.D'Incà R., Annese V., Di Leo V., et al. Increased intestinal permeability and NOD2 variants in familial and sporadic Crohn's disease. Alimentary Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 2006;23(10):1455–1461. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2006.02916.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Buhner S., Buning C., Genschel J., et al. Genetic basis for increased intestinal permeability in families with Crohn's disease: role of CARD15 3020insC mutation? Gut. 2006;55(3):342–347. doi: 10.1136/gut.2005.065557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kevans D., Turpin W., Madsen K., et al. Determinants of intestinal permeability in healthy first-degree relatives of individuals with Crohn's disease. Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. 2015;21(4):879–887. doi: 10.1097/mib.0000000000000323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Irvine E. J., Marshall J. K. Increased intestinal permeability precedes the onset of Crohn's disease in a subject with familial risk. Gastroenterology. 2000;119(6):1740–1744. doi: 10.1053/gast.2000.20231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Chichlowski M., Hale L. P. Bacterial-mucosal interactions in inflammatory bowel disease—an alliance gone bad. The American Journal of Physiology—Gastrointestinal and Liver Physiology. 2008;295(6):G1139–G1149. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.90516.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hugot J.-P., Chamaillard M., Zouali H., et al. Association of NOD2 leucine-rich repeat variants with susceptibility to Crohn's disease. Nature. 2001;411(6837):599–603. doi: 10.1038/35079107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ogura Y., Bonen D. K., Inohara N., et al. A frameshift mutation in NOD2 associated with susceptibility to Crohn's disease. Nature. 2001;411(6837):603–606. doi: 10.1038/35079114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hampe J., Franke A., Rosenstiel P., et al. A genome-wide association scan of nonsynonymous SNPs identifies a susceptibility variant for Crohn disease in ATG16L1. Nature Genetics. 2007;39(2):207–211. doi: 10.1038/ng1954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Parkes M., Barrett J. C., Prescott N. J., et al. Sequence variants in the autophagy gene IRGM and multiple other replicating loci contribute to Crohn's disease susceptibility. Nature Genetics. 2007;39(7):830–832. doi: 10.1038/ng2061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.McCarroll S. A., Huett A., Kuballa P., et al. Deletion polymorphism upstream of IRGM associated with altered IRGM expression and Crohn's disease. Nature Genetics. 2008;40(9):1107–1112. doi: 10.1038/ng.215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Petnicki-Ocwieja T., Hrncir T., Liu Y.-J., et al. Nod2 is required for the regulation of commensal microbiota in the intestine. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2009;106(37):15813–15818. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0907722106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Nighot P. K., Hu C. A., Ma T. Y. Autophagy enhances intestinal epithelial tight junction barrier function by targeting claudin-2 protein degradation. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2015;290(11):7234–7246. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.597492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Willing B., Halfvarson J., Dicksved J., et al. Twin studies reveal specific imbalances in the mucosa-associated microbiota of patients with ileal Crohn's disease. Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. 2009;15(5):653–660. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Rehman A., Sina C., Gavrilova O., et al. Nod2 is essential for temporal development of intestinal microbial communities. Gut. 2011;60(10):1354–1362. doi: 10.1136/gut.2010.216259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Fava F., Danese S. Intestinal microbiota in inflammatory bowel disease: friend of foe? World Journal of Gastroenterology. 2011;17(5):557–566. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v17.i5.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Martin T. D., Chan S. S. M., Hart A. R. Environmental factors in the relapse and recurrence of inflammatory bowel disease: a review of the literature. Digestive Diseases and Sciences. 2015;60(5):1396–1405. doi: 10.1007/s10620-014-3437-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Rodiño-Janeiro B. K., Alonso-Cotoner C., Pigrau M., Lobo B., Vicario M., Santos J. Role of corticotropin-releasing factor in gastrointestinal permeability. Journal of Neurogastroenterology and Motility. 2015;21(1):33–50. doi: 10.5056/jnm14084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Wyatt J., Vogelsang H., Hübl W., Waldhöer T., Lochs H. Intestinal permeability and the prediction of relapse in Crohn's disease. The Lancet. 1993;341(8858):1437–1439. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(93)90882-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.D'Incà R., Di Leo V., Martines D., et al. Can permeability to sugars predict relapses in Crohn's disease? Gut. 1993;34(1, supplement):S50–S73. [Google Scholar]

- 82.D'Incà R., Di Leo V., Corrao G., et al. Intestinal permeability test as a predictor of clinical course in Crohn's disease. The American Journal of Gastroenterology. 1999;94(10):2956–2960. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9270(99)00500-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Di Leo V., D'Incà R., Diaz-Granado N., et al. Lactulose/mannitol test has high efficacy for excluding organic causes of chronic diarrhea. The American Journal of Gastroenterology. 2003;98(10):2245–2252. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9270(03)00703-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Caccaro R., D'Incà R., Martinato M., et al. Fecal lactoferrin and intestinal permeability are effective non-invasive markers in the diagnostic work-up of chronic diarrhea. BioMetals. 2014;27(5):1069–1076. doi: 10.1007/s10534-014-9745-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Ukabam S. O., Clamp J. R., Cooper B. T. Abnormal small intestinal permeability to sugars in patients with Crohn’s disease of the terminal ileum and colon. Digestion. 1983;27(2):70–74. doi: 10.1159/000198932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Andre F., Andre C., Emery Y., Forichon J., Descos L., Minaire Y. Assessment of the lactulose—mannitol test in Crohn's disease. Gut. 1988;29(4):511–515. doi: 10.1136/gut.29.4.511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Wyatt J., Oberhuber G., Pongratz S., et al. Increased gastric and intestinal permeability in patients with Crohn's disease. American Journal of Gastroenterology. 1997;92(10):1891–1896. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Meddings J. B., Sutherland L. R., Byles N. I., Wallace J. L. Sucrose: a novel permeability marker for gastroduodenal disease. Gastroenterology. 1993;104(6):1619–1626. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(93)90637-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.van Wijck K., Verlinden T. J. M., van Eijk H. M. H., et al. Novel multi-sugar assay for site-specific gastrointestinal permeability analysis: a randomized controlled crossover trial. Clinical Nutrition. 2013;32(2):245–251. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2012.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Bjarnason I., O'Morain C., Levi A. J., Peters T. J. Absorption of 51-chromium-label ethylenediaminoacetate in inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 1983;85(2):318–322. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Jenkins R. T., Ramage J. K., Jones D. B., Collins S. M., Goodacre R. L., Hunt R. H. Small bowel and colonic permeability to 51Cr-EDTA in patients with active inflammatory bowel disease. Clinical and Investigative Medicine. 1988;11(2):151–155. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Pironi L., Miglioli M., Ruggeri E., et al. Relationship between intestinal permeability to [51Cr]EDTA and inflammatory activity in asymptomatic patients with Crohn's disease. Digestive Diseases and Sciences. 1990;35(5):582–588. doi: 10.1007/bf01540405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Becker V., von Delius S., Bajbouj M., Karagianni A., Schmid R. M., Meining A. Intravenous application of fluorescein for confocal laser scanning microscopy: evaluation of contrast dynamics and image quality with increasing injection-to-imaging time. Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. 2008;68(2):319–323. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2008.01.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Canto M. I., Anandasabapathy S., Brugge W., et al. In vivo endomicroscopy improves detection of Barrett's esophagus-related neoplasia: a multicenter international randomized controlled trial (with video) Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. 2014;79(2):211–221. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2013.09.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Bok G. H., Jeon S. R., Cho J. Y., et al. The accuracy of probe-based confocal endomicroscopy versus conventional endoscopic biopsies for the diagnosis of superficial gastric neoplasia (with videos) Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. 2013;77(6):899–908. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2013.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Shahid M. W., Buchner A. M., Heckman M. G., et al. Diagnostic accuracy of probe-based confocal laser endomicroscopy and narrow band imaging for small colorectal polyps: a feasibility study. The American Journal of Gastroenterology. 2012;107(2):231–239. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2011.376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Shahid M. W., Buchner A. M., Coron E., et al. Diagnostic accuracy of probe-based confocal laser endomicroscopy in detecting residual colorectal neoplasia after EMR: a prospective study. Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. 2012;75(3):525.e1–533.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2011.08.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Leong R. W. L. Confocal endomicroscopy in the evaluation of celiac disease. Endoscopy. 2010;42(7, article 607) doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1255541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Zambelli A., Villanacci V., Buscarini E., Bassotti G., Albarello L. Collagenous colitis: a case series with confocal laser microscopy and histology correlation. Endoscopy. 2008;40(7):606–608. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1077376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Fritscher-Ravens A., Schuppan D., Ellrichmann M., et al. Confocal endomicroscopy shows food-associated changes in the intestinal mucosa of patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2014;147(5):1012–1020.e3. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2014.07.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Kiesslich R., Goetz M., Angus E. M., et al. Identification of epithelial gaps in human small and large intestine by confocal endomicroscopy. Gastroenterology. 2007;133(6):1769–1778. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Liu J. J., Madsen K. L., Boulanger P., Dieleman L. A., Meddings J., Fedorak R. N. Mind the gaps. Confocal endomicroscopy showed increased density of small bowel epithelial gaps in inflammatory bowel disease. Journal of Clinical Gastroenterology. 2011;45(3):240–245. doi: 10.1097/mcg.0b013e3181fbdb8a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Lim L. G., Neumann J., Hansen T., et al. Confocal endomicroscopy identifies loss of local barrier function in the duodenum of patients with Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis. Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. 2014;20(5):892–900. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0000000000000027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Kiesslich R., Duckworth C. A., Moussata D., et al. Local barrier dysfunction identified by confocal laser endomicroscopy predicts relapse in inflammatory bowel disease. Gut. 2012;61(8):1146–1153. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2011-300695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Buda A., Hatem G., Neumann H., et al. Confocal laser endomicroscopy for prediction of disease relapse in ulcerative colitis: a pilot study. Journal of Crohn's and Colitis. 2014;8(4):304–311. doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2013.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Suenaert P., Bulteel V., Vermeire S., Noman M., Van Assche G., Rutgeerts P. Hyperresponsiveness of the mucosal barrier in Crohn's disease is not tumor necrosis factor-dependent. Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. 2005;11(7):667–673. doi: 10.1097/01.mib.0000168371.87283.4b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Sanderson I. R., Boulton P., Menzies I., Walker-Smith J. A. Improvement of abnormal lactulose/rhamnose permeability in active Crohn's disease of the small bowel by an elemental diet. Gut. 1987;28(9):1073–1076. doi: 10.1136/gut.28.9.1073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Teahon K., Smethurst P., Pearson M., Levi A. J., Bjarnason I. The effect of elemental diet on intestinal permeability and inflammation in Crohn's disease. Gastroenterology. 1991;101(1):84–89. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(91)90463-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Chapman-Kiddell C. A., Davies P. S. W., Gillen L., Radford-Smith G. L. Role of diet in the development of inflammatory bowel disease. Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. 2010;16(1):137–151. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Hildebrandt M. A., Hoffmann C., Sherrill-Mix S. A., et al. High-fat diet determines the composition of the murine gut microbiome independently of obesity. Gastroenterology. 2009;137(5):1716.e2–1724.e2. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.08.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Serino M., Luche E., Gres S., et al. Metabolic adaptation to a high-fat diet is associated with a change in the gut microbiota. Gut. 2012;61(4):543–553. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2011-301012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Martinez-Medina M., Denizot J., Dreux N., et al. Western diet induces dysbiosis with increased E coli in CEABAC10 mice, alters host barrier function favouring AIEC colonisation. Gut. 2014;63(1):116–124. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2012-304119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Lerner A., Matthias T. Changes in intestinal tight junction permeability associated with industrial food additives explain the rising incidence of autoimmune disease. Autoimmunity Reviews. 2015;14(6):479–489. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2015.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Andrade M. E., Araújo R. S., de Barros P. A. V., et al. The role of immunomodulators on intestinal barrier homeostasis in experimental models. Clinical Nutrition. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2015.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Pastorelli L., Salvo C. D., Mercado J. R., Vecchi M., Pizarro T. T. Central role of the gut epithelial barrier in the pathogenesis of chronic intestinal inflammation: Lessons learned from animal models and human genetics. Frontiers in Immunology. 2013;4, article 280 doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2013.00280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Finnie I. A., Dwarakanath A. D., Taylor B. A., Rhodes J. M. Colonic mucin synthesis is increased by sodium butyrate. Gut. 1995;36(1):93–99. doi: 10.1136/gut.36.1.93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Barcelo A., Claustre J., Moro F., Chayvialle J.-A., Cuber J.-C., Plaisancié P. Mucin secretion is modulated by luminal factors in the isolated vascularly perfused rat colon. Gut. 2000;46(2):218–224. doi: 10.1136/gut.46.2.218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Mariadason J. M., Barkla D. H., Gibson P. R. Effect of short-chain fatty acids on paracellular permeability in Caco-2 intestinal epithelium model. American Journal of Physiology—Gastrointestinal and Liver Physiology. 1997;272(4) part 1:G705–G712. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1997.272.4.G705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Peng L., He Z., Chen W., Holzman I. R., Lin J. Effects of butyrate on intestinal barrier function in a Caco-2 cell monolayer model of intestinal barrier. Pediatric Research. 2007;61(1):37–41. doi: 10.1203/01.pdr.0000250014.92242.f3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Hamer H. M., Jonkers D., Venema K., Vanhoutvin S., Troost F. J., Brummer R.-J. Review article: the role of butyrate on colonic function. Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 2008;27(2):104–119. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2007.03562.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Plöger S., Stumpff F., Penner G. B., et al. Microbial butyrate and its role for barrier function in the gastrointestinal tract. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2012;1258(1):52–59. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2012.06553.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Venkatraman A., Ramakrishna B. S., Pulimood A. B., Patra S., Murthy S. Increased permeability in dextran sulphate colitis in rats: time course of development and effect of butyrate. Scandinavian Journal of Gastroenterology. 2000;35(10):1053–1059. doi: 10.1080/003655200451171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Vernia P., Annese V., Bresci G., et al. Topical butyrate improves efficacy of 5-ASA in refractory distal ulcerative colitis: results of a multicentre trial. European Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2003;33(3):244–248. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2362.2003.01130.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Lorenz-Meyer H., Bauer P., Nicolay C., et al. Omega-3 fatty acids and low carbohydrate diet for maintenance of remission in Crohn's disease. A randomized controlled multicenter trial. Scandinavian Journal of Gastroenterology. 1996;31(8):778–785. doi: 10.3109/00365529609010352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Stremmel W., Merle U., Zahn A., Autschbach F., Hinz U., Ehehalt R. Retarded release phosphatidylcholine benefits patients with chronic active ulcerative colitis. Gut. 2005;54(7):966–971. doi: 10.1136/gut.2004.052316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Stremmel W., Ehehalt R., Autschbach F., Karner M. Phosphatidylcholine for steroid-refractory chronic ulcerative colitis: a randomized trial. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2007;147(9):603–610. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-147-9-200711060-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Roy S. K., Behrens R. H., Haider R., et al. Impact of zinc supplementation on intestinal permeability in Bangladeshi children with acute diarrhoea and persistent diarrhoea syndrome. Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition. 1992;15(3):289–296. doi: 10.1097/00005176-199210000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Alam A. N., Sarker S. A., Wahed M. A., Khatun M., Rahaman M. M. Enteric protein loss and intestinal permeability changes in children during acute shigellosis and after recovery: effect of zinc supplementation. Gut. 1994;35(12):1707–1711. doi: 10.1136/gut.35.12.1707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Di Leo V., D'Incà R., Barollo M., et al. Effect of zinc supplementation on trace elements and intestinal metallothionein concentrations in experimental colitis in the rat. Digestive and Liver Disease. 2001;33(2):135–139. doi: 10.1016/S1590-8658(01)80068-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Sturniolo G. C., Di Leo V., Ferronato A., D'Odorico A., D'Inc R. Zinc supplementation tightens ‘leaky gut’ in Crohn's disease. Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. 2001;7(2):94–98. doi: 10.1097/00054725-200105000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Sturniolo G. C., Fries W., Mazzon E., Di Leo V., Barollo M., D'Inca R. Effect of zinc supplementation on intestinal permeability in experimental colitis. Journal of Laboratory and Clinical Medicine. 2002;139(5):311–315. doi: 10.1067/mlc.2002.123624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Wang W., Chen L., Zhou R., et al. Increased proportions of Bifidobacterium and the Lactobacillus group and loss of butyrate-producing bacteria in inflammatory bowel disease. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 2014;52(2):398–406. doi: 10.1128/jcm.01500-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Jonkers D., Penders J., Masclee A., Pierik M. Probiotics in the management of inflammatory bowel disease. A systematic review of intervention studies in adult patients. Drugs. 2012;72(6):803–823. doi: 10.2165/11632710-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Vilela E. G., Ferrari M. D. L. D. A., Torres H. O. D. G., et al. Influence of Saccharomyces boulardii on the intestinal permeability of patients with Crohn's disease in remission. Scandinavian Journal of Gastroenterology. 2008;43(7):842–848. doi: 10.1080/00365520801943354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Zakostelska Z., Kverka M., Klimesova K., et al. Lysate of probiotic Lactobacillus casei DN-114 001 ameliorates colitis by strengthening the gut barrier function and changing the gut microenvironment. PLoS ONE. 2011;6(11) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0027961.e27961 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Patel R. M., Myers L. S., Kurundkar A. R., Maheshwari A., Nusrat A., Lin P. W. Probiotic bacteria induce maturation of intestinal claudin 3 expression and barrier function. American Journal of Pathology. 2012;180(2):626–635. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2011.10.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Ukena S. N., Singh A., Dringenberg U., et al. Probiotic Escherichia coli nissle 1917 inhibits leaky gut by enhancing mucosal integrity. PLoS ONE. 2007;2(12) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001308.e1308 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Persborn M., Gerritsen J., Wallon C., Carlsson A., Akkermans L. M. A., Söderholm J. D. The effects of probiotics on barrier function and mucosal pouch microbiota during maintenance treatment for severe pouchitis in patients with ulcerative colitis. Alimentary Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 2013;38(7):772–783. doi: 10.1111/apt.12451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Machiels K., Joossens M., Sabino J., et al. A decrease of the butyrate-producing species roseburia hominis and faecalibacterium prausnitzii defines dysbiosis in patients with ulcerative colitis. Gut. 2014;63(8):1275–1283. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2013-304833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Marteau P. Butyrate-producing bacteria as pharmabiotics for inflammatory bowel disease. Gut. 2013;62(12, article 1673) doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2012-304240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Moeinian M., Ghasemi-Niri S. F., Mozaffari S., et al. Beneficial effect of butyrate, Lactobacillus casei and L-carnitine combination in preference to each in experimental colitis. World Journal of Gastroenterology. 2014;20(31):10876–10885. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i31.10876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Simmons J. D., Mullighan C., Welsh K. I., Jewell D. P. Vitamin D receptor gene polymorphism: association with Crohn's disease susceptibility. Gut. 2000;47(2):211–214. doi: 10.1136/gut.47.2.211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Dresner-Pollak R., Ackerman Z., Eliakim R., Karban A., Chowers Y., Fidder H. H. The BsmI vitamin D receptor gene polymorphism is associated with ulcerative colitis in Jewish Ashkenazi patients. Genetic Testing. 2004;8(4):417–420. doi: 10.1089/gte.2004.8.417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Li Y. C., Chen Y., Du J. Critical roles of intestinal epithelial vitamin D receptor signaling in controlling gut mucosal inflammation. The Journal of Steroid Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. 2015;148:179–183. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2015.01.011.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Wu S., Zhang Y.-G., Lu R., et al. Intestinal epithelial vitamin D receptor deletion leads to defective autophagy in colitis. Gut. 2015;64(7):1082–1094. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2014-307436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.O'Sullivan M. Vitamin D as a novel therapy in inflammatory bowel disease: new hope or false dawn? Proceedings of the Nutrition Society. 2015;74(1):5–12. doi: 10.1017/s0029665114001621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]