Abstract

Background

Mobilization of the innate immune response to clear and metabolize necrotic and apoptotic cardiomyocytes is a prerequisite to heart repair after cardiac injury. Suboptimal kinetics of dying myocyte clearance leads to secondary necrosis, and in the case of the heart, increased potential for collateral loss of neighboring non-regenerative myocytes. Despite the importance of myocyte phagocytic clearance during heart repair, surprisingly little is known about its underlying cell and molecular biology.

Objective

To determine if phagocytic receptor MERTK is expressed in human hearts and to elucidate key sequential steps and phagocytosis efficiency of dying adult cardiomyocytes, by macrophages.

Results

In infarcted human hearts, expression profiles of the phagocytic receptor MER-tyrosine kinase (MERTK) mimicked that found in experimental ischemic mouse hearts. Electron micrographs of myocardium identified MERTK signal along macrophage phagocytic cups and Mertk−/− macrophages contained reduced digested myocyte debris after myocardial infarction. Ex vivo co-culture of primary macrophages and adult cardiomyocyte apoptotic bodies revealed reduced engulfment relative to resident cardiac fibroblasts. Inefficient clearance was not due to the larger size of mycoyte apoptotic bodies, nor were other key steps preceding the formation of phagocytic synapses significantly affected; this included macrophage chemotaxis and direct binding of phagocytes to myocytes. Instead, suppressed phagocytosis was directly associated with myocyte-induced inactivation of MERTK, which was partially rescued by genetic deletion of a MERTK proteolytic susceptibility site.

Conclusion

Utilizing an ex vivo co-cultivation approach to model key cellular and molecular events found in vivo during infarction, cardiomyocyte phagocytosis was found to be inefficient, in part due to myocyte-induced shedding of macrophage MERTK. These findings warrant future studies to identify other cofactors of macrophage-cardiomyocyte cross-talk that contribute to cardiac pathophysiology.

Keywords: Acute myocardial infarction, Animal models of human disease, Cardiomyocyte, Phagocytosis

Introduction

Following cardiac stress or myocardial infarction, the innate immune response, comprised of cells including neutrophils and monocytes/macrophages, are mobilized to (Frangogiannis, Smith et al. 2002; Nahrendorf, Swirski et al. 2007) or within (Epelman, Lavine et al. 2014) the infarcted myocardium to clear necrotic and apoptotic cardiomyocytes (CMs) (Whelan, Kaplinskiy et al. 2010) and promote wound repair (Lambert, Lopez et al. 2008; Zhang, Dehn et al. 2014). Inefficient clearance of dying CMs has been associated with suboptimal tissue remodeling after heart attack (Bujak, Kweon et al. 2008).

Phagocytic recognition of dying cells is a multi-step process (Ravichandran 2011) that requires chemotactic-recruitment (Elliott, Chekeni et al. 2009) of phagocytes, receptor-mediated binding of target-cell to phagocyte at a phagocytic synapse, and internalization and metabolism of dying cells (Fadok, Bratton et al. 1998; Henson, Bratton et al. 2001; Elliott and Ravichandran 2010). Whereas efficient and rapid phagocytosis of apoptotic cells (efferocytosis) activates pro-resolving/anti-inflammatory pathways in the phagocyte (Serhan and Savill 2005), defective or delayed efferocytosis leads to secondary post-apoptotic necrosis and expansion of tissue necrosis (Vandivier, Henson et al. 2006). Although the mechanisms of efferocytosis of dying cells in general have been extensively studied, in contrast, the cell biology of CM clearance has escaped detailed examination.

Our recent findings in a mouse model of myocardial infarction are consistent with the concept that phagocytic clearance of dying CMs is a significant causal factor in the mitigation of cardiac necrosis and heart failure (Wan, Yeap et al. 2013). Other studies have examined myocyte phagocytosis in skeletal muscle or in neonates in the context of autoimmunity (Briassouli, Komissarova et al. 2010), however, macrophage-mediated phagocytosis of adult-differentiated-CMs remains uncharacterized. In this context, the following studies were undertaken to model in vivo cardiac inflammation and elucidate rate limiting and ultimately therapeutically targetable, molecular steps during the recognition and removal of dying CMs by macrophages.

Materials and Methods

Materials

Chemical reagents were from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, MO) unless stated otherwise. Tissue culture dishes were from Corning, and fetal bovine serum (FBS) was from GIBCO. Antibodies: MERTK polyclonal antibody was from R&D. Anti-CD68 for IHC was obtained from Abcam (ab125212). Anti-actinin and monoclonal mouse anti-Desmin (clone DE-U-10) from mouse ascities fluid was from Sigma (D1033).

Primers for semi-quantitative and real-time PCR in this study

Mertk: F (forward oligonucleotide): GTG GCA GTG AAG ACC ATG AAG TTG, R (reverse oligo: GAA CTC CGG GAT AGG GAG TCA T. Ccl2 (MCP1): F: CCT GGA TCG GAA CCA AAT GA, R: ACC TTA GGG CAG ATG CAG TTT TA. Tnf-α: F: CGG AGT CCG GGC AGG T, R: GCT GGG TAG AGA ATG GAT GAA CA. Il-6: F: GAG GAT ACC ACT CCC AAC AGA CC, R: AAG TGC ATC ATC GTT GTT CATACA, Il-10: F: GCC AAG CCT TAT CGG AAA TG, R: GGG AAT TCA AAT GCT CCT TGA T. Gapdh: F: GGT GGC AGA GGC CTT TG, R: TGC CCA TTT AGC ATC TCC TT. The Mertk primers have previously been described (Camenisch, Koller et al. 1999; Thorp, Cui et al. 2008).

Animals

WT and Mertk−/− littermate controls were used in this study after Mertk +/− heterozygous mating. Unless otherwise stated, mice were male and 8-12 weeks of age; Mertk dependency for cardiomyocyte phagocytosis was also found in female mice. Mertk mice were backcrossed 10x to a C57BL/6 background. Mice initially described as MertkKD are referred to herein as Mertk−/− (Scott, McMahon et al. 2001). B6;D2-Tg(Myh6*-mCherry)2Mik/J mice were from Jackson. Mice were housed in temperature- and humidity-controlled environments (20 +/− 2°C and 55 +/− 10% relative humidity) and kept on a 12:12 hour day-night cycle with access to standard mouse chow and water ad libitum. All studies were approved and reviewed by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) at Northwestern University, Chicago, IL.

Histology

Human hearts were obtained from Northwestern University Department of Pathology and Universiteit Antwerpen in Belgium. See Supplementary Table 1 for patient profiles. Supplementary Figure 3 describes human analysis and as follows: Analysis of human samples was from patients >50years old. A total of 19 human hearts with evidence of inflammatory necrosis were examined. Within each heart, two regions of interest were measured: One inflammatory necrotic ROI and one remote ROI (Supplemental Figure). For each ROI, a minimum of 100 non-myocyte nuclei were assayed for MERTK expression to ascertain % MERTK positive cells. Under the protocol approved by the institutional review board at Northwestern University, #STU00079445, archived formalin fixed paraffin embedded cardiac autopsy samples were obtained through the Department of Pathology. Murine hearts were infused and fixed with 10% phosphate-buffered formalin at physiological pressures. Hearts were cut transversely, parallel to the atrioventricular groove/coronary sulcus. Fixed hearts were embedded in paraffin at the Northwestern University Mouse Histology and Phenotyping Laboratory (MHPL). Blocks were serially cut 6 μm apart. Alternating sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin. For frozen sections for immunohistochemistry, samples were rinsed and incubated overnight in 7% sucrose and frozen in freezing medium and examined at 4 days post MI unless otherwise indicated. Transverse cryosections were cut at a thickness of 10 μm on a Leica cryostat and placed on super frost plus-coated slides.

Laser Capture Microdissection (LCM), RT-QPCR, and qPCR

RNA from myocardial sections was captured by LCM using a Zeiss P.A.L.M. laser microdissection system as previously described by authors herein (Thorp 2011). Total RNA was isolated using the RNAqueous-Micro kit from Ambion and reverse-transcribed into cDNA using SuperScript III First-Strand Synthesis Mix (Invitrogen). For semi-quantitative and Quantitative RT-PCR: Hearts were snap-frozen for RNA. Total RNA was extracted using the RNeasy kit (Qiagen). cDNA was synthesized from 4 μg of total RNA using oligo (dT) and Superscript II (Invitrogen). cDNA was subjected to quantitative RT-PCR amplification using a SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems).

In vivo efferocytosis assays with cardiac mCherry reporter mice

For in vivo assays, myocardial infarction was induced in 8-12 week old mice as previously described and after ligating the left anterior descending artery (Wan, Yeap et al. 2013). Transgenic Myh6-driven mCherrry mice were subjected to aforementioned surgery and flow cytometry of myocardial extract was performed 4 days post MI to identify CD64, mCherry double positive cells. Cells were trypsinzed to dissociate cell-cell interactions and reveal only internalized mCherry signal.

Ex vivo efferocytosis and co-cultivations of primary adult cardiomyocytes (CMs) and macrophages

Adult mouse CMs and cardiac fibroblasts from 10-week-old mice were isolated using a modified Langendorff apparatus as previously described (O'Connell, Rodrigo et al. 2007). Briefly, hearts were cannulated via the aorta, perfused and ventricular cells were digested in a spinner flask with Collagenase II for 10 minutes. Heart cells were pre-plated on tissue-culture treated dishes for 1hr and non-adherent cells, i.e., CMs, were used for engulfment assays. Bone marrow cells were cultured in DMEM medium with 10% fetal bovine serum, 1% penicillin-streptomyocin and 20% L929 cell-conditioned media for 10 days. 2.5×105 bone marrow macrophages were stained with Calcein AM or as described in quadruplicate in 24 well plates and overlayed with 0.5×105 R18-labeled apoptotic or non-apoptotic primary, H9C2, or AC16 CMs. For the induction of apoptosis, CMs were UV-treated for 7mins and cells were incubated at 37°C for 2 h and 4h respectively. After incubation, the phagocytes were co-cultured with the CMs at 37°C for 30 and 60 minutes, and then washed thoroughly with PBS to remove non-engulfed cells. Cells were fixed in 2% PFA and percent phagocytosis was calculated as the number of R18, Calcein AM positive macrophages divided by the total number of Calcein AM positive macrophages.

Imaging: Time lapse video microscopy, confocal microscopy, and electron microscopy. Time lapse and confocal microscopy was performed on a Zeiss microscope. For EM, Epoxy resin was partially corroded by etching the sections for 10 seconds in saturated sodium ethoxide diluted to 50% with absolute ethanol. After rehydration and washing in distilled water, antigen retrieval was carried out by heating the sections for 10 min to 95°C and then cooling them to 21C at a rate of 0.04C/sec in a thermocycler UNO-Thermoblock (Biometra; Göttingen, Germany). After washing in three changes of PBS, nonspecific protein binding was blocked by incubation with 5% albumin in saline for 30 min at room temperature. Incubation with the various primary antibodies was carried out overnight at 4C. After application of the 10-nm gold-labeled secondary antibody for 60 minutes at room temperature at a concentration of 0.8 μg/ml and subsequent washing in saline, the immunoreaction was stabilized with 2.5% glutaraldehyde in PBS for 10 min (Merighi, Cruz et al. 1992). The sections were counterstained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate and examined in an electron microscope (Zeiss EM 10 CR) at an acceleration voltage of 80 kV.

Protein analysis

Myocardial extracts of ventricular tissue were homogenized in 10 mM HEPES pH 7.4, 320 mM sucrose, 3 mM MgCl2, 25 mM Na2P4O2, 1mM DTT, 5mM EGTA, 20mM NaF, and 2mM Na3VO4 with protease inhibitor cocktail. Protein extracts were subjected to SDS-PAGE. Anti-MERTK antibody and anti-cleaved CASPASE-3 antibodies were used for immuno-detection. For detection of soluble-MER: aliquots of cardiac extract were treated with 10 U of protein N-glycosidase F (PNGase F) from New England Biolabs for 1 hour at 37°C.

Statistical Analysis

Results are presented as means +/− SEM. Differences between multiple groups were compared by analysis of variance (1- or 2-way ANOVA and Bonferroni post-test), and differences between 2 groups were compared by paired or unpaired Student t test. A p value of < 0.05 was considered to be significant. Stated “n” values are biological replicates.

Results

MERTK+ mononuclear cells juxtapose damaged cardiomyocytes (CMs) in human myocardium

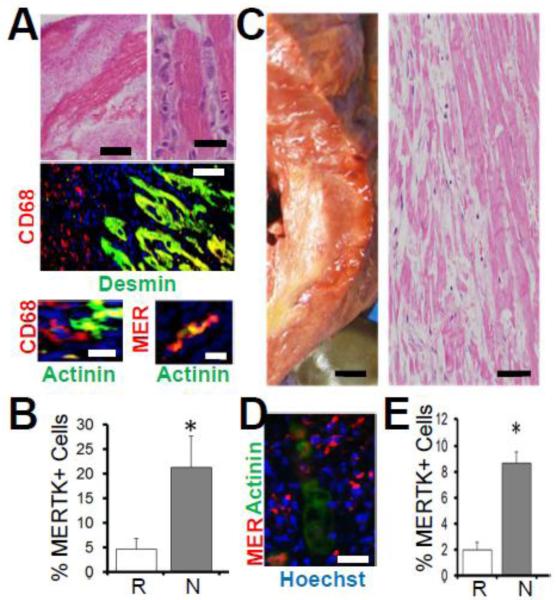

A previous study from our group (Wan, Yeap et al. 2013) tested the causal significance of macrophage-mediated phagocytosis to cardiac repair by experimentally inducing myocardial infarction in the absence of the specific macrophage cell-surface marker (Gautier, Shay et al. 2012) and apoptotic cell receptor MER tyrosine kinase (MERTK) (Scott, McMahon et al. 2001). To test the human significance of our findings, we obtained human hearts post autopsy and compared MERTK expression in mouse hearts versus human. Figure 1 shows the expected accumulation of hematoxylin positive mononuclear (Fig.1A), CD68 and MERTK immuno-positive cells closely juxtaposed to eosinophilic and Desmin and Actinin positive CMs, and were further elevated (Fig.1B) in necrotic murine myocardial areas. Similar to mouse, human cardiac autopsy sections (Fig.1C) revealed increased MERTK immuno-positive mononuclear cells proximal to human CMs (Fig.1D and Supplemental Figure 4). Although no differences in MERTK expression were found between immune cells of heathy hearts and the remote areas of infarcted hearts, increased MERTK+ cells were measured in areas of inflammatory/necrotic myocardium (Fig.1E), consistent with a direct role for MERTK during CM interactions in human heart.

Fig. 1. Evidence for MERTK in human myocardium.

A and B is mouse ischemic myocardium and C,D,E is human. (A) Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E) images of mouse myocardium showing hematoxylin+ mono-nuclear cells juxtaposed to hyper-eosinophilic cardiomyocytes. Left scale bar is 500μm and right is 20μm. Below H&E micrographs are Immunohistochemistry (IHC) of mouse heart with indicated markers for macrophages (CD68 and MER-TK) and cardiomyocytes (Desmin & Actinin). CD68 vs Desmin bar = 50μm. Bottom images = 10μm. In (B), results of IHC quantification in Remote (R) vs inflammatory Necrotic (N) myocardial ROIs (regions of interest). (C, D, E) Human Myocardium. (C) Left is cross-section of myocardium from gross autopsy showing yellow infarct and right is H&E histology of same heart. Left is 0.5cm scale and right is 50μm scale bar. (D) IHC (100μm) with indicated markers (hoechst are nuclei) and (E) quantitation of MERTK positive signal in healthy/Remote versus inflammatory/Necrotic myocardial ROIs.

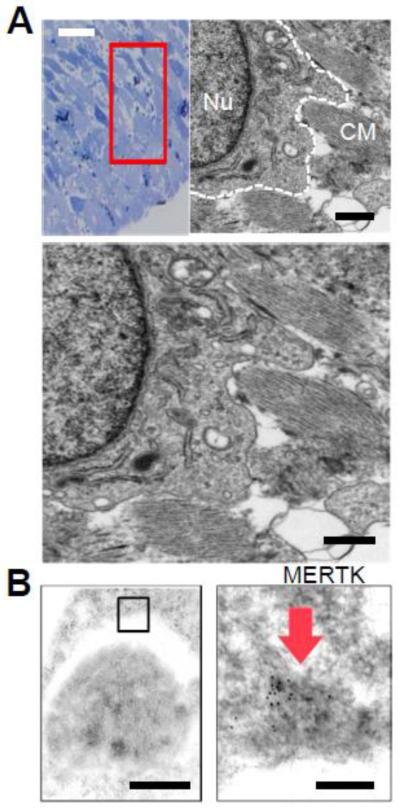

MERTK localizes to phagocytic cups in ischemic myocardium

To identify MERTK localization in heart at the subcellular level, we imaged ischemic mouse myocardium by transmission electron microscopy (TEM). Cardiac sections were chosen with evidence of inflammatory cell infiltration after TEM-compatible toluidine staining (Fig.2A). Ultrastructural images readily identified surveying phagocytes with phagocytic vacuoles, electron-dense lysosomes and extended filopodia-like structures surrounding striated myocardial debris. Immunogold TEM (Fig.2B) revealed MERTK signal (absent in Mertk−/− hearts) that localized to phagocytic cups and were interacting with target cells that were positive for myocyte markers Desmin and Actinin. Interestingly, Mertk−/− phagocytes in situ seemingly exhibited reduced filopodia-formation (data not shown), similar to that observed in other cell-culture studies where MERTK was inhibited (Tang, Wu et al. 2015).

Fig. 2. Evidence for MERTK at the phagocytic cup in myocardium.

(A) Toluidine blue staining of cardiac sections after experimental infarction and selection of region of interest with mono-nuclear infiltration for transmission electron microscopy. TEM image to the right shows putative cardiac macrophage (outlined in white dotted line) and its nucleus (Nu) with extended pseudopods proximal to remnants of striated cardiomyocyte (CM) debris. Image is magnified below. Black bar = 2 micrometers. (B) Phagocytic pseudopod on top surrounding an apoptotic body that was found to be immunopositive for CM markers Desmin and Actinin. Right: MERTK immunogold staining identified on the phagocytic pseudopod. Black bars = 500 nanometers to the left and 50 nanometers to the right.

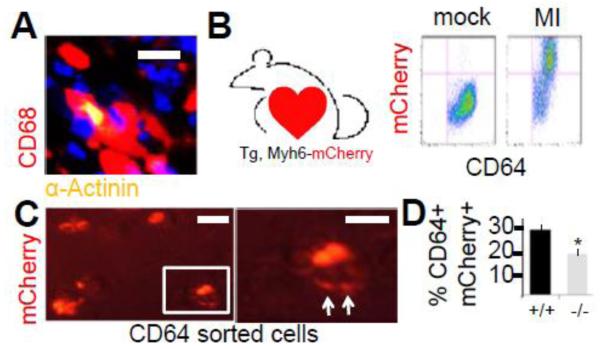

MERTK is required for CM-internalization and digestion in cardiac-derived macrophages

Our past methodologies for quantifying engulfment efficiencies in heart relied on immuno-histochemical co-localization of dying CMs with macrophages (Fig.3A)(Wan, Yeap et al. 2013). Alternative approaches to measure phagocytic activity in heart include optical imaging tomography on injected/ingested probes (Swirski and Nahrendorf 2013) and flow cytometric co-staining (Epelman, Lavine et al. 2014). To definitively test for internalization of CM-derived proteins and any requirement for MERTK, macrophages were isolated by flow cytometry after experimental infarction of mice that were transgenic for cardiomyocyte-specific expression of the mCherry reporter gene. Figure 3B shows that 4 days after experimental infarction, significant levels of mCherry signal co-localized with CD64+ macrophages. Importantly, direct microscopic imaging of CD64+ sorted cells, revealed mCherry digestion patterns (Fig.3C) in macrophages that were isolated after light trypsin digestion to dissociate cell-cell binding. Internalization was separately confirmed by confocal microscopy. Importantly, Mertk deficiency reduced the extent of CD64+ sorted macrophages containing internalized CM mCherry signal (Fig.3D).

Fig. 3. MERTK-dependent internalization of cardiomyocytes by macrophages in myocardium.

(A) Immunohistochemistry shows co-localization of CD68+ macrophages with actinin+ cardiomyocytes (yellow). Scale bar = 15 micrometers. (B) Transgenic Myh6-driven mCherrry mouse and flow cytograms from myocardial extracts post left anterior descending artery ligation (MI) to induce infarction. MI induces CD64, mCherry double positive cells. (C) CD64+ sorted cells were imaged by fluorescent microscopy for macrophages containing myocardial mCherry signal. Cells were trypsinzed to dissociate cell-cell interactions and reveal only internalized mCherry signal. Image to the right is an enlargement of the boxedin cell, displaying evidence of mCherry digestion (arrows). Scale bar = 15 micrometers. (D) Quantitation of myocardial mCherry internalization in Mertk−/− mice vs. Mertk+/+ mice after MI.

Having (1) revealed expression of MERTK in human hearts, (2) identified MERTK-signal in situ on myocardial phagocytic cups, and (3) validated macrophage internalization and digestion of CMs post infarction, we next co-cultivated primary macrophages with primary adult differentiated CMs ex vivo to examine CM phagocytosis in more detail at the cell and molecular level.

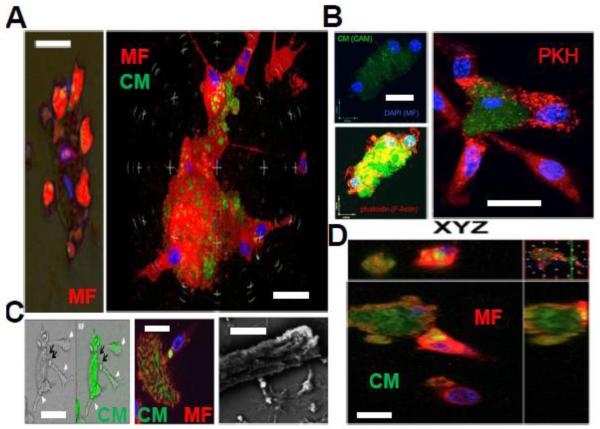

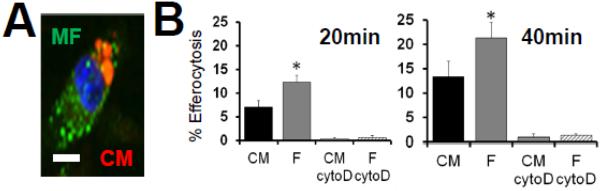

Co-cultivations reveal cooperative and piece-meal phagocytic processing of dying CMs

Our co-cultivations utilized bone-marrow derived mouse macrophages and primary mouse adult differentiated CMs. Minutes after overlaying macrophages onto dying CMs, brightfield and immuno-epifluroscent microscopy revealed a high ratio of phagocytes engaging and enveloping rod-shaped early-apoptotic CMs (Fig.4A). The average macrophage : CM ratio was 3.7:1, in contrast to observed ~1:1 ratios between macrophages and cardiac fibroblasts. After staining macrophages with either filamentous actin probe phalloidin or high-affinity aliphatic membrane dye PKH, extensive phagocyte membrane remodeling was observed on macrophages interacting with CMs (Fig.4B). When CMs were labeled with cytosolic dyes and co-cultured with macrophages for longer durations (>15 minutes), evidence of phagocytic uptake was documented as dye transfer from the CM to macrophage (Fig.4C). Interestingly, engulfment of CM apoptotic bodies appeared to occur in a piece-meal fashion, consistent with trimming of dying CM apoptotic bodies away from the CM-core. Scanning Electron microscopy showed macrophages seemingly extending pseudopodia along CM surface furrows to promote ingestion. Internalization of CM bodies into macrophages was confirmed by confocal microscopy (Fig.4D) and consistent with internalization of CM debris, CM bodies co-localized with lysosomal marker lysosomal-associated membrane protein 1 (LAMP1) (Jehle, Gardai et al. 2006) (Supplemental Figure 5). Finally, CM engulfment required actin polymerization, as engulfment was suppressed after separately treating macrophages with inhibitor of actin polymerization cytochalsin-D (Supplemental Figure 6).

Fig. 4. Ex vivo co-cultivations reveal macrophage attraction to dying cardiomyocytes (CMs) and piece-meal phagocytic processing.

(A) Left epi-fluorescent and brightfield merged image displays red pseudo-colored (Calcein-AM/CAM) macrophages (MF) and CM that are solely labeled with DAPI for nuclei. Multiple macrophages engage the singular adult CM. To the right, confocal image shows multiple (nuclei are blue from DAPI) red-immunostained macrophages (F4/80) enveloping green a CM. Scale bars = 30μm. (B) Evidence of membrane remodeling in MFs upon binding to CMs. Top left shows multiple DAPI-labeled MFs bound to a CAM labelled CM. Below cells are stained for Filamentous Actin (F-actin) dye phalloidin in red. Phalloidin reveals actin polymerization of phagocytes surrounding the CM core. To the right, MFs labelled with membrane dye PKH and CMs are green. MFs directly interacting with CMs show redistribution of PKH dye. Scale bars = 20 μm. (C) Evidence of piece-meal phagocytosis. Left images show green-labeled CMs transferring green dye to attached macrophages (MF, arrowheads). Middle confocal image shows phagocyte appearing to internalize green signal from CM in a phagosome. Right image is scanning electron micrograph of CM and attached MFs appearing to internalize bright/refractile apoptotic bodies. Scale bars = 15 μm. (D) Internalization of green CM apoptotic bodies into green MFs confirmed by confocal microscopy Z sections. Scale bar = 20 μm.

CM efferocytosis is inefficient

CM death post MI occurs by both necrosis and apoptosis (Whelan, Kaplinskiy et al. 2010). CM apoptotic death is found in the zone that borders the infarct area at times that coincide with cardiac MERTK expression (Wan, Yeap et al. 2013). Furthermore, apoptotic bodies by nature of their phosphatidylserine can signal pro-reparative signals in the phagocyte (Fadok, Bratton et al. 1998), which likely participate in cardiac wound healing. Therefore we focused on macrophage engulfment of CM apoptotic bodies. To standardize our initial analyses, we chose to utilize a well-characterized apoptotic inducer, the protein kinase inhibitor staurosporine (STS). We chose a dose of STS that mimicked kinetics of apoptosis similar to that observed during ischemia-induced apoptosis (Supplemental Figure 1). As a first approximation of the efficiency of CM efferocytosis, we performed phagocytic assays in comparison to apoptotic cardiac fibroblasts. To achieve this, separate adherent monolayers of CMs and fibroblasts were induced to apoptosis and early non-adherent apoptotic bodies collected, clarified by low speed centrifugation to isolate apoptotic bodies from larger cells, and equivalent numbers of apoptotic bodies overlaid onto phagocytes at a ratio of 5 apoptotic bodies to 1 phagocyte. Figure 5 shows that relative to actin-dependent uptake of cardiac fibroblasts, engulfment of apoptotic bodies from CMs was less efficient (on average 23.7% less than cardiac fibroblasts).

Fig. 5. Inefficient Phagocytic Uptake of CM apoptotic bodies (ABs).

(A) Micrograph of epiflourescent macrophage (green) engulfing red cardiomyocyte (CM) apoptotic bodies. Scale bar = 7μm. (B) Primary resident cardiac fibroblasts (F) and adult ventricular myocytes were adhered onto tissue culture plates and induced to apoptosis (1 hour 1μM staurosporine/STS followed by 6hr treatment for CF and 18hr CF to achieve ~80% morphological cell death). Non-adherent/floating apoptotic bodies were harvested and separated from larger-CM-core bodies by low-speed centrifugation at 50 x g to isolate apoptotic bodies from cells and overlaid under saturating conditions onto adherent primary bone-marrow derived macrophages for efferocytosis enumeration. Cytochalasin D (cytoD) was added to macrophages to inhibit actin polymerization and control for engulfment-specificity vs. non-specific binding.

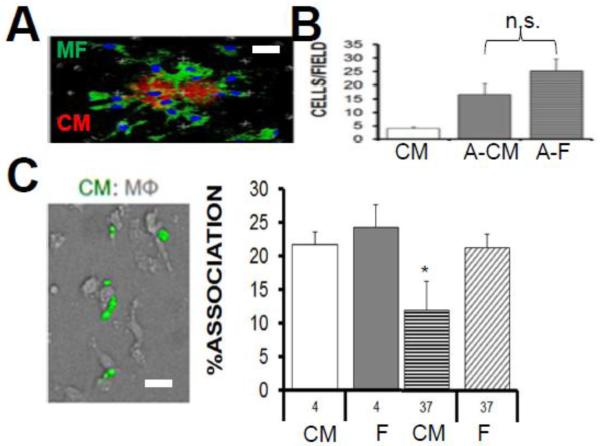

Unlike CM efferocytosis, chemotaxis and binding to CMs was not significantly reduced

We next considered that other stages of CM phagocytosis might also be attenuated relative to cardiac fibroblasts. Phagocytosis during inflammation requires the chemotactic migration of phagocytes to dying cells, followed by intercellular binding to form the phagocytic synapse. To test the ability of macrophages to chemotax to dying CMs, transwell cultures were utilized. Figure 6 shows that relative to apoptotic fibroblasts, macrophages migrated to dying CMs at an efficiency that trended lower, but was not statistically significant. We also measured tethering of CM-apoptotic bodies to macrophages at 4°C and did not find evidence of reduced binding, relative to apoptotic fibroblasts. Rather, macrophage affinities for dying CMs trended higher, versus fibroblasts. Furthermore, corroborative video microscopy (on a Bio-Station Video Microscope station; see Supplemental Figure 2) also showed macrophages with CM attachments that were maintained, even after collapse of rod-shaped CMs into large apoptotic bodies. When 4°C cultures were thermo-shifted to 37°C, defects in engulfment were revealed, suggesting that the mechanism of inefficient uptake was at the level of internalization, after chemotaxis and binding.

Fig. 6. Steps Leading (Chemotaxis) and Preceding (Binding) Engulfment of Cardiomyocytes do Not Differ Significantly Relative to Cardiac Fibroblasts.

(A) Macrophages (green) swarm to apoptotic cardiomyocytes (CM) (red). Scale bar = 20μm. (B) Bar graph displays quantification of macrophage chemotaxis to live CMs vs apoptotic cardiomyocytes (A-CMs) versus apoptotic cardiac fibroblasts (A-F). n.s.=not statistically different. (C) Micrograph shows green CM apoptotic bodies bound to non-labeled macrophages. Binding assay bar graph for affinity of macrophages to dying CMs versus dying cardiac fibroblasts (F) at temperature of 4C. After thermoshift to 37C and rinsing away of non-engulfed cells, % association in an indication of engulfment. Scale bar is 15 μm.

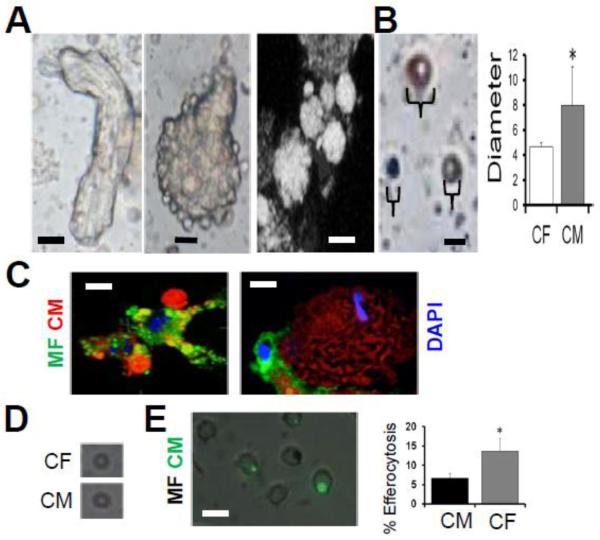

Inefficient efferocytosis is not associated with CM large apoptotic body size

Phagocytic removal of dying CMs is a unique challenge in that myocytes are larger than macrophages. Nevertheless, previous studies have shown that phagocytes can engulf particles as large as themselves (Cannon and Swanson 1992; Aderem 2002). Consistently, (Maruyama, Takemura et al. 2001), apoptotic bodies of large and heterogenous size blebbed off the larger cardiomyocyte core after apoptosis induction (Fig.7). Direct quantitation and flow cytometric analysis indicated that on average, CM apoptotic bodies were larger than apoptotic bodies from cardiac fibroblasts. Microscopic images revealed macrophages interacting with apoptotic bodies of diverse sizes. To determine if large CM apoptotic body size affects efferocytosis efficiency, we normalized size by size exclusion filtration to remove larger apoptotic bodies, and overlaid onto macrophages. As indicated in Figure 7D, overlay of filtered apoptotic bodies from CMs and cardiac fibroblasts revealed that CMs were still less efficiently engulfed. These data suggested a contributing molecular factor in the reduced phagocytic phenotype.

Fig. 7. Inefficient Cardiomyocyte (CM) efferocytosis is largely independent of the size of CM apoptotic bodies.

(A) Leftmost bright-field image depicts rod-shaped CM in the beginning stages of cell death. To the immediate right is a collapsed rounded CM exhibiting protruding apoptotic body blebs. Next image is confocal microscopy and shows apoptotic bodies of varying sizes forming on a dying CM. Scale bars = 15μm. (B) Soluble apoptotic bodies (ABs) of various sizes are depicted in photomicrograph. Scale bar = 4 μms. Quantification of CM vs cardiac fibroblast (CF) apoptotic body size. (C) Phagocytes engage CM ABs of various sizes. Scale bar is 10μm. (D) Average size of largest CM and CF apoptotic bodies after filtration was <5 μms. (E) Normalized efferocytosis after filtration with size exclusion filter. Scale bar is 10μm.

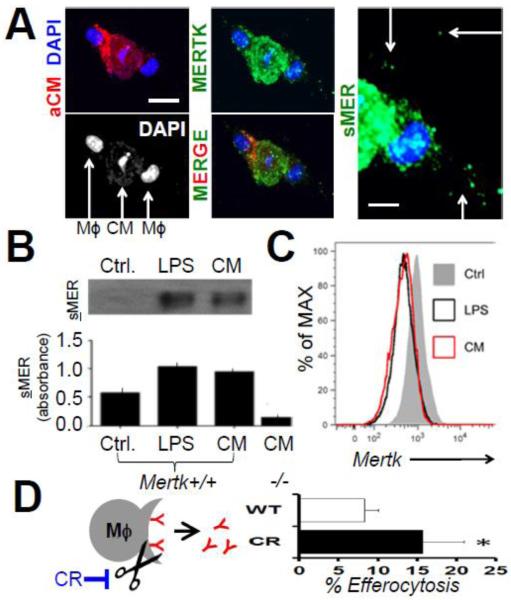

CMs induce shedding of macrophage apoptotic cell receptor MERTK to reduce efferocytosis efficiency

Multiple mechanisms on the CM or macrophage-side could explain reduced efferocytosis efficiencies. We recently reported evidence of lower molecular weight MER isoforms in extracts of cardiac tissue post ischemia, consistent with shedding of MER ectodomains from cardiac macrophage cell surfaces (Wan, Yeap et al. 2013). Shedding of MER, after its cleavage by proteolysis, can reduce efferocytosis efficiency during inflammation by inhibiting post-binding engulfment signaling (Sather, Kenyon et al. 2007; Thorp, Vaisar et al. 2011). Interestingly, our co-cultivation experiments exposed extra-cellular speckles of MER immuno-staining, consistent with shedding of MER (Fig 8). We therefore measured cell surface MERTK levels by flow cytometry, after co-cultivation with CMs, and found significantly reduced MERTK signal. Western blots and ELISA also revealed elevated shed, or soluble-MER in the supernatant of macrophages that were co-cultivated with dying CMs. To test if inefficient CM phagocytosis could be enhanced by blockade of MERTK cleavage, we transfected Mertk-deficient HEK cells with wild type Mertk cDNA, and compared phagocytic efficiency relative to our previously characterized cleavage resistant (cr) Mertk cDNA (Thorp, Vaisar et al. 2011), in which the protease susceptibility site has been genetically deleted. Fig. 8D shows that relative to cells transfected with equal masses of WT Mertk, cells harboring the crMERTK isoform promoted enhanced CM efferocytosis.

Fig. 8. Dying Cardiomyocytes (CMs) Induce MERTK Cleavage in Macrophages to Inhibit Efferocytosis.

(A) Confocal images of dying Red (PKH) labeled CMs were cocultivated with MERTK-labeled (green) macrophages. DAPI shows macrophage nuclei flanking condensed apoptotic CM nuclei. Scale bar = 20μm. Rightmost panel depicts higher magnification image (white bar = 10 μms) of extracellular (arrows) or soluble MER (sMER) signal. (B) Western blots (above) and ELISA (below) for solMER after Mertk+/+ or Mertk−/− macrophage incubation with positive control lipopolysaccharide (LPS) or CMs. (C) Flow cytometry histograms for cell-surface MERTK after co-cultivation with LPS or CMs (D). Schematic representation of inhibition of sMER cleavage with mutant Cleavage-Resistant (CR) MERTK. Bar graph is enumeration of % CM efferocytosis by HEK293 cells after transfection with equal masses of wild type (WT) vs CR-Mertk cDNAs.

Discussion

Herein our study examined in vivo validated and rate limiting steps before and during CM engulfment by macrophages. Our focus was on modeling pathways similarly present or required during myocardial wound healing (Figure 1) (Wan, Yeap et al. 2013). From these studies, perhaps it is not surprising that macrophage phagocytosis of cardiomyocytes (CMs) was found to be inefficient relative to other parenchymal cell types. For example, the inflammatory response after myocardial infarction (MI) is likely not shaped by selective evolutionary forces, in that the average age of first MI is well after reproductive years. Similarly, and at the cellular level, the long-lived nature and terminally differentiated state of adult CMs limits their phagocytic engagement by phagocyte receptors, in comparison to other cell types with higher turnover kinetics.

Although the predominant form of CM death post MI is necrosis (Whelan, Kaplinskiy et al. 2010), the significance of apoptotic CMs and their apoptotic bodies are important to examine. For example, apoptotic recognition of non-myocytes is amplified through phosphatidylserine-receptors and other pathways in macrophages, which can transmit intracellular signals to suppress inflammation and promote tissue repair (Serhan and Savill 2005). However, it remains to be conclusively tested as to how recognition of CM apoptotic bodies may regulate macrophage inflammatory signaling. This is an important consideration as potential defects in engulfment, coupled with inefficient activation of pro-resolving immunosuppressive pathways, could cumulatively delay cardiac repair. Given the low regenerative potential of CMs, even slight delays in resolution of cardiac inflammation could promote collateral CM loss and therefore reduce cardiac contractility.

A unique aspect of CMs in the setting of phagocytosis is their larger size. Our data indicate minimal changes to efferocytosis efficiency, as a function of CM apoptotic body surface area (Figure 7). Studies that have examined phagocytic target size and geometry, indicate particle diameter per se is not the sole factor in triggering actin-mediated engulfment (Champion and Mitragotri 2006). Case in point, morphology of the engulfed particle can affect eating efficiency. For example, filamentous bacteria delay timing of phagocytosis through induction of unique phagosome maturation pathways (Tollis, Dart et al. 2010). It will be interesting to determine if larger or stiffer hypertrophic CMs, after pressure overload-associated cardiac syndromes for example, are uniquely engulfed and processed by phagocytes, or alternatively result in unique inflammatory phagocyte polarization (Canton 2014). Also important for inflammation resolution is the fate of the large and last CM apoptotic body or “core,” which often represents the final remnant of CM apoptosis (Maruyama, Takemura et al. 2001).

On the phagocyte side, an important macrophage receptor in cardiac repair is MERTK (Wan, Yeap et al. 2013)

During experimental myocardial infarction, evidence suggests that the ectodomain of MERTK is shed from cell surfaces, and our initial analyses indicate this also occurs in humans (data not show). Proteolytic cleavage is known to regulate the activity of many transmembrane anchored proteins. In the case of MERTK, recombinant soluble-MER is modulatory by two accounts: First through suppression of efferocytosis and secondly through affecting thrombus formation in vivo (Sather, Kenyon et al. 2007). MERTK inactivation by ADAM17-medated cleavage is predicted to suppress its anti-inflammatory function, thereby permitting the phagocyte to become fully activated (Thorp, Vaisar et al. 2011). Ex vivo enhancement of CM efferocytosis by cleavage-resistant MERTK was significant (Figure 8), however does not rule out other potential contributing mechanisms that affect CM phagocytic efficiency, including on the CM. In addition to identifying potential CM-specific triggers of MERTK cleavage, future studies seeking the physiological relevance of MERTK cleavage post heart attack, will benefit from the identification and blockade of its cleavage site.

Additional future studies that model CM clearance pathways should address the role of neutrophils both separately and together with macrophages. This is important in that neutrophils are recruited to the heart prior to monocytes and may contribute to the breakdown of dying muscle cells. Also, cellular cardiac tissue scaffolds (Freytes, Santambrogio et al. 2012) may reveal the nature of macrophages with CMs in a more natural three dimensional setting. On the CM side, broader unresolved questions include the identity of CM ligands necessary for interactions with macrophages. On the macrophage, and in the setting of a heterogeneous cardiac macrophage population (Epelman, Lavine et al. 2014), distinct phagocyte subsets may promote alternative phagosome maturation pathways and immune responses (Underhill and Goodridge 2012). In preliminary data, flow cytometry-sorted macrophages from mouse hearts reproduced findings reported herein, however, additional studies should test mechanisms of varying phagocytosis efficiency by these ontogenically unique phagocyte subsets (Epelman, Lavine et al. 2014). We anticipate that further studies of macrophage-CM interactions will reveal new strategies to enhance CM clearance efficiency, reduce infarct size, and improve cardiac function.

Supplementary Material

Highlights (3-5 bullet points max 85 characters per bullet) for.

Cardiomyocytes Induce Macrophage Receptor Shedding to Suppress hagocytosis, Zhang et al.

MERTK is expressed in human hearts

MERTK-deficiency inhibits internalization of cardiomyocyte debris

Cardiomyocytes are inefficiently engulfed by macrophages.

Cardiomyocytes induce MERTK shedding to reduce phagocytosis

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Ira Tabas MD, PhD @ Columbia University for studies of cleavage-resistant MERTK. Funding provided by 1R01HL122309-01. Also, this work was funded by the Chicago Biomedical Consortium with support from the Searle Funds at The Chicago Community Trust. Thanks to Alex Larson MD for help with gross examination of cardiac autopsy samples.

Abbreviations

- CM

Cardiomyocyte

- CF

Cardiofibroblast

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Aderem A. How to eat something bigger than your head. Cell. 2002;110(1):5–8. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00819-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briassouli P, Komissarova EV, et al. Role of the urokinase plasminogen activator receptor in mediating impaired efferocytosis of anti-SSA/Ro-bound apoptotic cardiocytes: Implications in the pathogenesis of congenital heart block. Circ Res. 2010;107(3):374–387. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.213629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bujak M, Kweon HJ, et al. Aging-related defects are associated with adverse cardiac remodeling in a mouse model of reperfused myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;51(14):1384–1392. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.01.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camenisch TD, Koller BH, et al. A novel receptor tyrosine kinase, Mer, inhibits TNF-alpha production and lipopolysaccharide-induced endotoxic shock. J Immunol. 1999;162(6):3498–3503. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cannon GJ, Swanson JA. The macrophage capacity for phagocytosis. J Cell Sci. 1992;101(Pt 4):907–913. doi: 10.1242/jcs.101.4.907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canton J. Phagosome maturation in polarized macrophages. Journal of leukocyte biology. 2014;96(5):729–738. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1MR0114-021R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Champion JA, Mitragotri S. Role of target geometry in phagocytosis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2006;103(13):4930–4934. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0600997103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott MR, Chekeni FB, et al. Nucleotides released by apoptotic cells act as a find-me signal to promote phagocytic clearance. Nature. 2009;461(7261):282–286. doi: 10.1038/nature08296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott MR, Ravichandran KS. Clearance of apoptotic cells: implications in health and disease. J Cell Biol. 2010;189(7):1059–1070. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201004096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epelman S, Lavine KJ, et al. Embryonic and adult-derived resident cardiac macrophages are maintained through distinct mechanisms at steady state and during inflammation. Immunity. 2014;40(1):91–104. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.11.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fadok VA, Bratton DL, et al. Macrophages that have ingested apoptotic cells in vitro inhibit proinflammatory cytokine production through autocrine/paracrine mechanisms involving TGF-beta, PGE2, and PAF. J Clin Invest. 1998;101(4):890–898. doi: 10.1172/JCI1112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frangogiannis NG, Smith CW, et al. The inflammatory response in myocardial infarction. Cardiovasc Res. 2002;53(1):31–47. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(01)00434-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freytes DO, Santambrogio L, et al. Optimizing dynamic interactions between a cardiac patch and inflammatory host cells. Cells Tissues Organs. 2012;195(1-2):171–182. doi: 10.1159/000331392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gautier EL, Shay T, et al. Gene-expression profiles and transcriptional regulatory pathways that underlie the identity and diversity of mouse tissue macrophages. Nature immunology. 2012;13(11):1118–1128. doi: 10.1038/ni.2419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henson PM, Bratton DL, et al. Apoptotic cell removal. Curr Biol. 2001;11(19):R795–805. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(01)00474-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jehle AW, Gardai SJ, et al. ATP-binding cassette transporter A7 enhances phagocytosis of apoptotic cells and associated ERK signaling in macrophages. J Cell Biol. 2006;174(4):547–556. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200601030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambert JM, Lopez EF, et al. Macrophage roles following myocardial infarction. Int J Cardiol. 2008;130(2):147–158. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2008.04.059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maruyama R, Takemura G, et al. Dynamic process of apoptosis in adult rat cardiomyocytes analyzed using 48-hour videomicroscopy and electron microscopy: beating and rate are associated with the apoptotic process. Am J Pathol. 2001;159(2):683–691. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)61739-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merighi A, Cruz F, et al. Immunocytochemical staining of neuropeptides in terminal arborization of primary afferent fibers anterogradely labeled and identified at light and electron microscopic levels. J Neurosci Methods. 1992;42(1-2):105–113. doi: 10.1016/0165-0270(92)90140-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nahrendorf M, Swirski FK, et al. The healing myocardium sequentially mobilizes two monocyte subsets with divergent and complementary functions. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2007;204(12):3037–3047. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Connell TD, Rodrigo MC, et al. Isolation and culture of adult mouse cardiac myocytes. Methods Mol Biol. 2007;357:271–296. doi: 10.1385/1-59745-214-9:271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravichandran KS. Beginnings of a good apoptotic meal: the find-me and eat-me signaling pathways. Immunity. 2011;35(4):445–455. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sather S, Kenyon KD, et al. A soluble form of the Mer receptor tyrosine kinase inhibits macrophage clearance of apoptotic cells and platelet aggregation. Blood. 2007;109(3):1026–1033. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-05-021634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott RS, McMahon EJ, et al. Phagocytosis and clearance of apoptotic cells is mediated by MER. Nature. 2001;411(6834):207–211. doi: 10.1038/35075603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serhan CN, Savill J. Resolution of inflammation: the beginning programs the end. Nat Immunol. 2005;6(12):1191–1197. doi: 10.1038/ni1276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swirski FK, Nahrendorf M. Leukocyte behavior in atherosclerosis, myocardial infarction, and heart failure. Science. 2013;339(6116):161–166. doi: 10.1126/science.1230719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang Y, Wu S, et al. Mertk Deficiency Affects Macrophage Directional Migration via Disruption of Cytoskeletal Organization. PloS one. 2015;10(1) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0117787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorp E, Cui D, et al. Mertk receptor mutation reduces efferocytosis efficiency and promotes apoptotic cell accumulation and plaque necrosis in atherosclerotic lesions of apoe−/− mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2008;28(8):1421–1428. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.108.167197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorp E, Vaisar T, et al. Shedding of the Mer tyrosine kinase receptor is mediated by ADAM17 protein through a pathway involving reactive oxygen species, protein kinase Cdelta, and p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) J Biol Chem. 2011;286(38):33335–33344. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.263020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorp EB. Methods and models for monitoring UPR-associated macrophage death during advanced atherosclerosis. Methods Enzymol. 2011;489:277–296. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-385116-1.00016-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tollis S, Dart AE, et al. The zipper mechanism in phagocytosis: energetic requirements and variability in phagocytic cup shape. BMC Syst Biol. 2010;4:149. doi: 10.1186/1752-0509-4-149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Underhill DM, Goodridge HS. Information processing during phagocytosis. Nat Rev Immunol. 2012;12(7):492–502. doi: 10.1038/nri3244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vandivier RW, Henson PM, et al. Burying the dead: the impact of failed apoptotic cell removal (efferocytosis) on chronic inflammatory lung disease. Chest. 2006;129(6):1673–1682. doi: 10.1378/chest.129.6.1673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wan E, Yeap XY, et al. Enhanced efferocytosis of apoptotic cardiomyocytes through myeloid-epithelial-reproductive tyrosine kinase links acute inflammation resolution to cardiac repair after infarction. Circ Res. 2013;113(8):1004–1012. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.113.301198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whelan RS, Kaplinskiy V, et al. Cell death in the pathogenesis of heart disease: mechanisms and significance. Annu Rev Physiol. 2010;72:19–44. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.010908.163111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang S, Dehn S, et al. Phagocyte-myocyte interactions and consequences during hypoxic wound healing. Cellular immunology. 2014;291(1-2):65–73. doi: 10.1016/j.cellimm.2014.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.