Abstract

Pilocarpine-induced status epilepticus (SE) is a widely used seizure model in mice, and the Racine scale has been used to index seizure intensity. The goal of this study was to analyze electroencephalogram (EEG) quantitatively using fast Fourier transformation (FFT) and statistically evaluate the correlation of electrographic seizures with convulsive behaviors. Simultaneous EEG and video recordings in male mice in a mixed genetic background were conducted and pilocarpine was administered intraperitoneally to induce seizures. The videos were graded using the Racine scale and the root-mean-square (RMS) power analysis of EEG was performed with Sirenia Seizure Pro software. We found that the RMS power was very weakly correlated with convulsive behavior induced by pilocarpine. Convulsive behaviors appeared long before electrographic seizures and showed a strong negative correlation with theta frequency activity and a moderate positive correlation with gamma frequency activity. Racine scores showed moderate correlations with RMS power across multiple frequency bands during the transition from first electrographic seizure to SE. However, there was no correlation between Racine scores and RMS power during the SE phase except a weak correlation with RMS power in the theta frequency. Our analysis reveals limitations of the Racine scale as a primary index of seizure intensity in status epilepticus, and demonstrates a need for quantitative analysis of EEG for an accurate assessment of seizure onset and severity.

Keywords: seizures, electroencephalogram, status epilepticus, Racine scale, pilocarpine, mice

1. Introduction

Behavioral scoring is commonly used to assess seizure intensity in various animal models of seizures. Racine's scale, originally developed for the amygdala-kindling model (Racine, 1972) to describe the progression of limbic seizures with secondary generalization (Pitkänen et al., 2006), has been frequently used as an intensity measurement in other experimental seizure or epilepsy models. Over the years, the Racine scale has been modified from its original simple form to better describe the progression of seizures induced by various chemical convulsants, with inclusions of additional stages (Borges et al., 2003; Kalueff et al., 2004; Lüttjohann et al., 2009; Turski et al., 1984). However, its validity as an index of electrographic seizure intensity has not been vigorously tested using quantitative analysis of the electroencephalogram (EEG) during seizure activity.

The EEG is a brain electrical signal that derives from postsynaptic potentials of cortical neurons. Power spectral analysis, which decomposes a signal into its constituent frequency components using the fast Fourier transformation, is a well-established method for the analysis and quantification of EEG signals. It has been used for many years in assessing wakefulness and stages of sleep (Dressler et al., 2004; Tafti, 2007), and has been applied recently in the analysis of seizures (Becker et al., 2008; Phelan et al., 2014). However, whether the EEG power spectrum during seizures correlates with convulsive behaviors described by the Racine scale has not been statistically evaluated.

Pilocapine-induced status epilepticus (SE) is one of the most widely used acute seizure models (Turski et al., 1989) and has been used to assess the effects of genetic manipulations on seizures in mice based on changes in the Racine scale. Thus, there is a need to assess the reliability of the Racine scale in this particular acute seizure model. We used a common electrode placement for rodent EEG recordings (Treiman et al., 1990), and applied statistical methods to determine the relationship between the Racine stage scoring of convulsive behaviors and the RMS power derived from EEG spectral analysis. We anticipated that Racine scores would roughly correlate with RMS power. To our surprise, our results revealed a complex relationship between EEG RMS power and convulsive behaviors described by the Racine scale that varies during the onset of cortical seizures but not after SE is established.

2. Methods

2.1. Surgery and EEG recording

All animal experiments were performed under protocols approved by the Intuitional Animal Use and Care Committee at the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences. Male mice in a mixed C57Blk/129sv genetic background were bred in house and housed under a 12 h light-dark cycle with food and water ad libitum. For EEG surgery, male mice (12–20 weeks old) were anaesthetized with Ketamine/xylazine or isoflurane. Stainless steel screws were used as electrodes, placed on top of the dura through small holes drilled through the skull and then fixed to the skull using dental cement. The locations of the front two electrodes (L1 and R1) were placed over motor cortex (approximately 1 mm anterior to Bregma and 1.5 mm lateral to midline; see the inset in Figure 1). The other two electrodes (L2 and R2) were placed approximately 1.5 mm anterior to Lambda and 1.5 mm lateral to the midline. The ground electrode (Gnd) was placed in the midline approximately 1.5 mm posterior of Lambda. EEG electrodes were wired to a head mount that was also fixed to the skull using dental cement. Since the wound was hermetically sealed by dental cement, post-operational analgesics and antibiotics were not used.

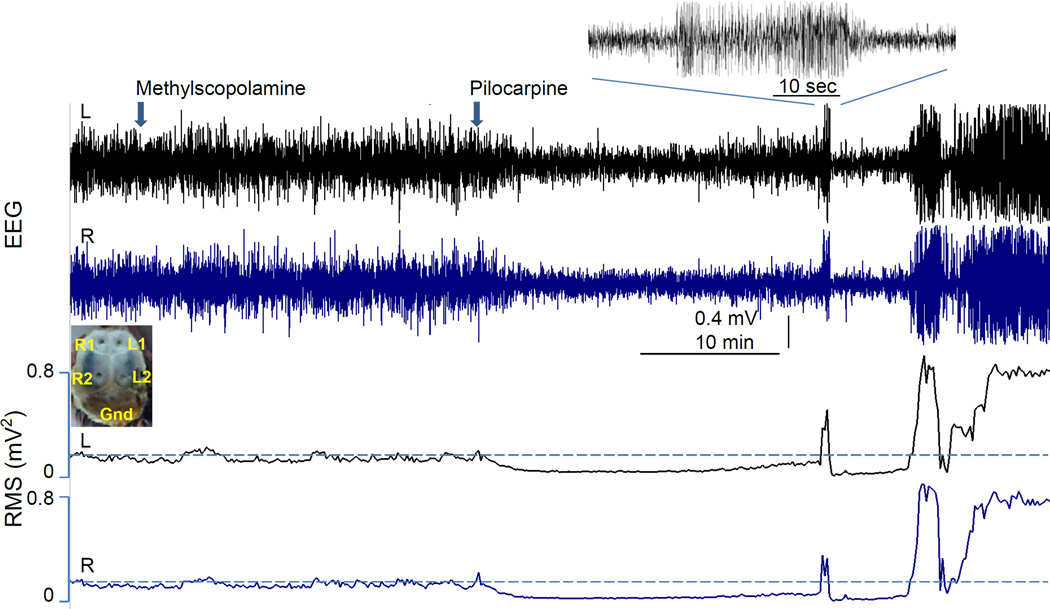

Figure 1. EEG recording and power analysis of pilocarpine-induced acute seizures in mice.

The top panel shows the EEG recordings from the left and right brain hemispheres before and after the administration of methylscopolamine and pilocarpine. The placements of EEG electrodes (from the perspective inside the skull) are shown in the inset. The bottom panel shows the root-mean-square (RMS) power value of the EEG signals on the same time scale as the raw EEG signals in the top panel. Note that there was little change in EEG activity after the administration of methylscopolamine, and there was an initial decrease in EEG activity after the administration of pilocarpine. Brief pilocarpine-induced seizures (shown in expanded time scale in the inset) then appear in both brain hemispheres and status epilepticus (SE) was eventually reached after two bursts of seizures.

After 5–7 days of recovery from the surgery, EEG signals and synchronized video were recorded using the Pinnacle 8200 system (Pinnacle Technology). The head mount was connected to a preamplifier tethered to the AD box. The voltage differential between the pair of electrodes from each brain hemisphere (L1 vs. L2; R1 vs. R2) were amplified with a high pass filter (1Hz) and recorded. EEG signals were sampled at 400 Hz and videos were recorded at 30 frames/sec.

2.2. Pilocarpine-induced SE

After more than 5 min of EEG and video recording of baseline activity, mice were first administered a single dose of methylscopolamine (1 mg/kg, i.p.) to block the peripheral effects of pilocarpine. A single dose of pilocarpine (280 mg/kg, i.p.) was administered approximately 25 min after methylscopolamine to induce acute seizures. The first ictal activity in the EEG was identified by RMS power analysis with a threshold of 270 µV2 using a 5 sec scanning window in 0.25 sec steps. This threshold is the 90% value of the mean RMS during the SE phase. The period preceding the first ictal activity was termed the latent period. The SE state was defined by a sustained large increase in the RMS power and the onset of SE was determined by scanning using the same RMS threshold. The transition period was defined as the time between the first ictal activity and the onset of SE.

2.3. Behavioral grading of seizures using the Racine scale

The video was scored for every minute for the first hour after pilocarpine injection. The scoring was based on the Racine scale, as described previously (Racine, 1972) with the following stages: 0, no abnormality; 1, Mouth and facial movements; (2) Head nodding; (3) Forelimb clonus; (4) Rearing; (5) Rearing and falling. A full motor seizure, with temporary loss of postural control, is referred to as a Stage 5 motor seizure.

2.4. Electroencephalographic spectral analysis

Fast Fourier power spectral analysis (FFT) of EEG signal was performed using Sirenia Seizure Pro software with a Hanning window applied to reduce spectral leakage. The band widths for the full, delta, theta, alpha, beta and gamma frequency bands were set as 0–1000 Hz, 0.5–4 Hz, 4.5–7.5 Hz, 8–13 Hz, 13–30 Hz, and 35–45 Hz, respectively. The RMS power values for all wave bands were calculated for each minute after pilocarpine administration by averaging the values of 6 consecutive 10-sec windows. The Racine stage scores were plotted against the corresponding RMS values. To determine the statistical dependence between the Racine scale (a discrete variable) and the RMS power of the EEG signal (a continuous variable), Spearman’s rank-order correlation coefficients (rs) were then calculated from pooled data from 5 mice. EEG signals from both hemispheres were processed for power spectra, and the RMS values exhibited a significant correlation (r=0.98±0.02, Pearson’s correlation test). Thus, only RMS values from the left hemisphere were used for further analysis. Pilot analysis of EEG and video using 10 second windows resulted in reduced rs values, indicating that the binning improves the detection of possible correlation between the RMS power and the Racine scores. The strength of correlation was categorized as very weak (0≤ rs <0.20), weak (0.20≤ rs <0.40), moderate (0.40≤ rs <0.60), strong (0.60≤ rs <0.80), or very strong (0.80≤ rs ≤1.00).

3. Results

After pilocarpine administration, there was a latent period (29±6 min, mean±S.D., n=5) characterized by a decrease in the full spectral RMS power (Fig.1) before the appearance of first ictal activities in the EEG (Fig.1, inset). The latent period was followed by a brief transition period (approximately 10–20 min) in which bursts of ictal activities were interrupted by a quiescent period of variable length that was often correlated with suppressed EEG activity and free of ictal activities. SE states were reached 34±8 min after the administration of pilocarpine. Our EEG data are consistent with previous reports (Mazzuferi et al., 2012; Müller et al., 2009; Pitsch et al., 2007; Turski et al., 1984).

To determine whether the behavioral scoring of seizures using the Racine scale correlates with the seizure intensity determined by the RMS power analysis of EEG, the video recordings were analyzed and a Racine score was assigned every minute for the 60 min after the administration of pilocarpine (Fig.2A). The video grading stopped earlier in some mice when mice exhibited flat EEG signals which indicated death. After administration of pilocarpine, the changes in cortical EEG signals underwent three phases (Phelan et al., 2014): (a) a latent period during which cortical EEG activity is suppressed; (b) a transition period which starts with the first ictal activity and ends with the establishment of cortical SE; and (c) the SE phase. It was quite noticeable that stage 2 and stage 3 behavioral scores in the latent period were not associated with ictal activities in the EEG (Fig.2B). It should also be noted that after the SE state was reached, mice exhibited no rearing or jumping behaviors, and stayed largely immobile with continuous oral facial movements and head nodding. Racine stages 4 and 5 were observed in the transition period toward the onset of SE, and were associated with intense ictal activities in the EEG (Fig.2B). These observations raise questions about the appropriateness of the Racine scale as an index of seizure severity in SE.

Figure 2. Simultaneous analysis of EEG and video recording after pilocarpine-induced seizures in mice.

A: The RMS power (filled circles) in the full band width of the EEG recording and the Racine stage scores (open circles) of the video recording from a single mouse were plotted against the time. The start and end of each seizure in EEG were plotted along the same time scale (red). The demarcation of the end of the latent period and the start of the SE state are indicated by vertical lines.

B: Sample raw EEG traces (at indicated time points in A) corresponding to various convulsive behaviors assigned to specific Racine stages. Scale bars: 0.8 mV, 1 sec.

To determine whether the Racine stage scoring correlates with the absolute RMS power, we plotted the Racine stage scores against the RMS power values pooled from 5 mice and calculated the Spearman’s rank-order correlation coefficients over a 60 min period after the administration of pilocarpine (Fig.3A). There was a very weak positive correlation between the Racine stage scores and the RMS power in the full spectrum over the whole period (Fig.3A). Weak positive correlations were also exhibited for delta, beta and gamma frequency bands, whereas there was no correlation between the Racine stage scores and theta activity or alpha activity (Fig.3A). To reduce inter-individual variability, we normalized the RMS power to the pre-pilocarpine baseline value and calculated the Spearman’s rank-order correlation coefficients between the relative RMS power and the Racine stage scores (Fig.3B). There was no statistically significant correlation between the relative RMS power in the full band width and the Racine stage scores, and very weak to weak correlations between the relative RMS power in the higher frequency bands (beta and gamma) and the Racine stage scores.

Figure 3. Spearman’s rank order correlation analysis of paired RMS power values and Racine stage scores over a 60 min-period after the administration of pilocarpine in mice.

Data were pooled from 5 mice and the number of total paired samples was 241. The correlation between the Racine stage scores and the absolute RMS power (A) or between the Racine stage scores and relative RMS power (B) were calculated and plotted. Note that the correlation between Racine scores and the absolute RMS power were mostly weak, and the Racine scores were weakly correlated only to relative RMS power of gamma activity.

To better assess the relationship between the RMS power and Racine stage scores, we analyzed data for each specific period (described in Fig.2) after the administration of pilocarpine. During the latent period (Fig.4A, B), there was no significant correlation between the Racine stage scores and the full spectral RMS power. Consistent with the observation that EEG activities were inhibited by pilocarpine during the latent period, there were weak negative correlations between the Racine scores and relative changes in delta, theta and alpha activities. On the other hand, both absolute and relative RMS powers in the gamma frequency band were positively correlated with Racine stage scores during the latent period.

Figure 4. Spearman’s rank order correlation analysis of paired RMS power values and Racine stage scores in the latent, transition, and SE period.

In the latent period (A,B), there is a lack of correlation between the RMS power in the full band width and the Racine scores, the negative correlations between the delta, theta and alpha waves and the Racine scores, and the positive correlation between the gamma wave and the Racine scores (n=149). In the transition period (C,D), in contrast to the latent period, there were strong positive correlations between the Racine scores and the RMS power in multiple wave bands (n=52). During the SE (E,F), there is a lack of correlation between the Racine score and the RMS power in all wave bands (n= 37).

The transition period was characterized by moderate positive correlations between the Racine stage scores and the RMS power in the full spectrum and in multiple frequency bands (Fig.4C, D). Thus, these observations are consistent with the notion that seizure behaviors and ictal EEG activity occur across a broad spectrum of frequencies.

The SE stage was more problematic for the Racine scale (Fig.4E, F). There was no correlation between Racine scores and the RMS power across most spectral bands except a weak correlation between RMS power and theta activity. This statistical finding is consistent with our empirical observations that once the SE state was established, the Racine stage scores stayed largely below Stage 4. Thus, the Racine stages appear to be a poor index of seizure intensity during the SE stage.

Taken together, our data show that there are stage-specific and complex relationships between the convulsive behaviors described by the Racine scale and EEG activities in various frequency bands. In general, the behaviors described by the lower end of the Racine scale are moderately correlated with primarily gamma activity, and are negatively correlated with the slower brain rhythms such as delta and theta. The Racine scale appears to be quite reliable during the transition period because we observed moderate correlations between Racine scores and EEG activities across all bands. However, once the SE state is fully established, the Racine scale fails to indicate the persistent high intensity seizures that are obvious in EEG recordings.

4. Discussion

Although the original Racine scale does not include all convulsive behaviors and we have previously used a modified Racine scale to describe pilocarpine-induced convulsive behavior in mice, we reverted to the original Racine scale in this study to make our results more generalizable. Our data suggest that the original Racine scale is a reliable indicator of seizure severity during the transition phase of pilocarpine-induced seizures in mice. There are several obstacles that prevent extension of the Racine scale beyond the transition period that will be difficult to overcome. The first issue is that some convulsive behaviors described by the lower end of the Racine scale occur in the absence of cortical seizures. This is not surprising since it has been reported that pilocarpine-induced seizures are initiated in the hippocampus (Turski et al., 1984), and the early behavioral manifestations do not involve motor cortex. It should be noted that the early seizures in the hippocampus may be the driving force behind the increased gamma wave activity in cortical EEG that shows moderate correlation with the convulsive behaviors during the latent period. Use of hippocampal EEG electrodes in mice is more challenging than in larger rodents, but might enable correlation of early seizure discharges with the earlier Racine stages. The second obstacle is the general absence of convulsive behaviors described by the higher end of the Racine scale after the onset of SE. In our experience, those convulsive behaviors described as Racine stage 4 and 5 are all brief events that last only several seconds. Their occurrences correspond with bursts of cortical seizures in the progression toward SE and the onset of SE. Use of the Racine scale would suggest that the mice were in a “mild” convulsive state (on the Racine scale) during the SE state beyond the currently scored time period, whereas EEG recordings suggest continuous high intensity cortical seizure activity. A previous study redefined Racine stage 5 as the SE state (Becker et al., 2008). This approach would be problematic since it is not based on clearly distinguishable behavioral categories. The original Racine stage 5 also included full hind limb extension and loss of posture (analogous to a tonic seizure), which is not observed in the regular amygdala kindling but can be induced by extended kindling (Pinel and Rovner, 1978). In our pilocarpine-induced SE model in mice, the tonic seizure is associated with a “flat lining” of cortical EEG signals, and frequently lead to death. This observation is consistent with a previous report that the brainstem is critically involved in the tonic phase (Browning and Nelson, 1986). We also analyzed the same data using the modified Racine scale and found similar correlations between the RMS of EEG signals and the convulsive behaviors. For these reasons, it is difficult to envision how further refinement of the Racine scale can extend its reliability beyond the brief transition period. However, behavioral correlates of EEG findings are key features of the “electroclinical syndrome” in human epilepsy and should still be monitored in animal models of seizures. Our findings only question the commonly accepted notion that Racine stages correlate with increased seizure severity, particularly in the later stages of status epilepticus.

Using the Racine scale alone without cortical EEG recordings could lead to misunderstanding of the epileptic state in the pilocarpine model. First, it would be difficult to identify the onset of SE based on behavioral observation alone. It is also difficult to determine whether a mouse has ever reached the SE state in some cases in which a single bout of stage 4–5 convulsive behaviors were scored. The latency to the first cortical seizures usually correlates with the appearance of the first bout of stage 4–5 convulsive behaviors. Multiple bouts of stage 4–5 convulsive behaviors suggest a full progression into the SE state, though cortical EEG makes this more certain. Likewise, cortical EEG recordings alone in absence of behavioral scoring would miss early stages of subcortical (hippocampal) seizure activity represented by Stage 1–3 Racine seizures. Similarly, the lack of stage 4–5 convulsive behaviors in late SE suggests that the mice are not having cortical seizures, whereas EEG recording clearly demonstrates ongoing seizure activity.

Our data indicates that, in contrast to behavior scoring using the Racine scale, the EEG spectral analysis is far more reliable and provides new information that will lead to better understanding of the initiation of seizures. The negative correlation between the slower wave bands (delta, theta, and alpha) and convulsive behaviors during the latent period is particularly intriguing. These slower waves have been associated with various normal brain functions, and theta activity in particular has been associated with consciousness (Dressler et al., 2004). In humans, the transition to the drowsy, non-alert state associated with drop-out of alpha frequency activity correlates with this finding. The negative correlation between slower activity and the convulsive behaviors is consistent with the loss of consciousness associated with convulsive behaviors. Given the fact that the gamma rhythm shows a positive correlation to convulsive behaviors during the same period, the interaction between these two frequency bands may be central to the seizure generation. Prior studies have identified gamma activity as dependent on cortical inhibition, particularly involving fast-spiking, parvalbumin-positive cortical interneurons (Sohal et al., 2009). The positive relationship of gamma power with seizure activity might be a correlate of increased activities of parvalbumin-positive interneurons at the cortical level.

An additional consideration is that there is no intrinsic reason that EEG power should correlate with seizure behaviors. The progression of Racine stages likely reflects the successive involvement of innate or well established motor programs (freezing, grooming, rearing) when seizure activity involves the areas of cortex in which these programs are initiated, and hence indicates spatial spread of seizure activity from the hippocampus to synaptically connected cortical areas rather than evolution of seizure frequencies or amplitude. In this sense, it is not surprising that we observed no seizure activities in cortical EEG that associated with Racine stage 1 and 2 during the latent period. However, it is presumed that the motor cortex should be involved in stage 3 and the lack of association with seizure activities in cortical EEG is surprising. One possibility is that the spatial resolution of mouse EEG recording may not be able to pick up focal partial seizures. Alternatively, stage 1–3 behaviors may be simply progressive hyperactivities of motor cortex in the high frequency gamma band, which correlates with Racine scores (Fig.4). The decoupling of Racine scores and cortical EEG seizures during SE cannot be explained by a lack of spatial resolution, as any seizures involving motor cortex would be detected even by sparse electrode sampling. As seizure activity persists, changes in neurotransmitter receptor function, including downregulation of GABAA receptors (Kapur and Macdonald, 1997) and upregulation of NMDA receptors (Chen and Wasterlain, 2006; Mazarati and Wasterlain, 1999) likely are involved in perpetuation of status and loss of the correlation between seizures and overt behaviors as measured by the Racine scale. Indeed, in humans, “uncoupling” of convulsive behavior with prolonged/medically refractory SE is the rule rather than the exception, and may indicate the failure of motor programs due to neuroplastic changes produced by continuous seizure activity.

Finally, our results confirm and expand upon those of Treiman et al. (Treiman et al., 1990) and Handforth and Ackermann (Handforth and Ackermann, 1992) demonstrating a sequence of electroencephalographic changes associated with the onset and progression of SE in both humans and rats. Treiman et al. reported a progression of EEG changes in human SE from (1) discrete seizures to (2) merging seizures with waxing and waning EEG amplitude and frequency to (3) continuous ictal activity to (4) continuous ictal activity punctuated by low voltage ‘flat periods’ to (5) periodic epileptiform discharges on a ‘flat’ background. We limited our analysis to the first 60 min after pilocarpine administration because extending the analysis further could reduce the potential correlation. In humans, this sequence has been controversial and varies significantly according to the electroclinical syndrome (Kaplan, 2006). Nevertheless, patterns of evolving EEG activity and correlation with observable behavior likely reflect the underlying pathophysiology, and can provide further insight into the mechanisms of SE.

Acknowledgement

Supported in part by NINDS (NS050381 to FZ), by the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences Bridging Fund (to FZ), by NIGMS (GM103425 to LJG), and by the Translational Research Institute through funding from NIH (UL1TR000039).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosure of Conflict of Interest:

None of the authors has any conflict of interest to disclose.

References

- Becker AJ, Pitsch J, Sochivko D, Opitz T, Staniek M, Chen C-C, Campbell KP, Schoch S, Yaari Y, Beck H. Transcriptional upregulation of Cav3.2 mediates epileptogenesis in the pilocarpine model of epilepsy. J. Neurosci. 2008;28:13341–13353. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1421-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borges K, Gearing M, McDermott DL, Smith AB, Almonte AG, Wainer BH, Dingledine R. Neuronal and glial pathological changes during epileptogenesis in the mouse pilocarpine model. Exp. Neurol. 2003;182:21–34. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4886(03)00086-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browning RA, Nelson DK. Modification of electroshock and pentylenetetrazol seizure patterns in rats after precollicular transections. Exp. Neurol. 1986;93:546–556. doi: 10.1016/0014-4886(86)90174-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen JWY, Wasterlain CG. Status epilepticus: pathophysiology and management in adults. Lancet. Neurol. 2006;5:246–256. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(06)70374-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dressler O, Schneider G, Stockmanns G, Kochs EF. Awareness and the EEG power spectrum: analysis of frequencies. British journal of anaesthesia. 2004 doi: 10.1093/bja/aeh270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Handforth A, Ackermann RF. Hierarchy of seizure states in the electrogenic limbic status epilepticus model: behavioral and electrographic observations of initial states and temporal progression. Epilepsia. 1992;33:589–600. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1992.tb02334.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalueff AV, Lehtimaki KA, Ylinen A, Honkaniemi J, Peltola J. Intranasal administration of human IL-6 increases the severity of chemically induced seizures in rats. Neurosci. Lett. 2004;365:106–110. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2004.04.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan PW. The EEG of status epilepticus. J. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2006;23:221–229. doi: 10.1097/01.wnp.0000220837.99490.66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapur J, Macdonald RL. Rapid seizure-induced reduction of benzodiazepine and Zn2+ sensitivity of hippocampal dentate granule cell GABAA receptors. J. Neurosci. 1997;17:7532–7540. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-19-07532.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lüttjohann A, Fabene PF, van Luijtelaar G. A revised Racine’s scale for PTZ-induced seizures in rats. Physiol. Behav. 2009;98:579–586. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2009.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazarati AM, Wasterlain CG. N-Methyl-D-asparate receptor antagonists abolish the maintenance phase of self-sustaining status epilepticus in rat. Neurosci. Lett. 1999;265:187–190. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(99)00238-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazzuferi M, Kumar G, Rospo C, Kaminski RM. Rapid epileptogenesis in the mouse pilocarpine model: Video-EEG, pharmacokinetic and histopathological characterization. Exp. Neurol. 2012;238:156–167. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2012.08.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller CJ, Gröticke I, Hoffmann K, Schughart K, Löscher W. Differences in sensitivity to the convulsant pilocarpine in substrains and sublines of C57BL/6 mice. Genes. Brain. Behav. 2009;8:481–492. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2009.00490.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phelan KD, Shwe UT, Abramowitz J, Birnbaumer L, Zheng F. Critical role of canonical transient receptor potential channel 7 in initiation of seizures. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2014;111:11533–11538. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1411442111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinel JP, Rovner LI. Experimental epileptogenesis: kindling-induced epilepsy in rats. Exp. Neurol. 1978;58:190–202. doi: 10.1016/0014-4886(78)90133-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitkänen A, Schwartzkroin P, Moshé S, editors. Models of seizures and epilepsy. London: Elsevier Academic Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Pitsch J, Schoch S, Gueler N, Flor PJ, van der Putten H, Becker aJ. Functional role of mGluR1 and mGluR4 in pilocarpine-induced temporal lobe epilepsy. Neurobiol. Dis. 2007;26:623–633. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2007.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Racine RJ. Modification of seizure activity by electrical stimulation. II. Motor seizure. Electroencephalogr. Clin. Neurophysiol. 1972;32:281–294. doi: 10.1016/0013-4694(72)90177-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sohal VS, Zhang F, Yizhar O, Deisseroth K. Parvalbumin neurons and gamma rhythms enhance cortical circuit performance. Nature. 2009;459:698–702. doi: 10.1038/nature07991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tafti M. Quantitative genetics of sleep in inbred mice. Dialogues Clin. Neurosci. 2007;9:273–278. doi: 10.31887/DCNS.2007.9.3/mtafti. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treiman DM, Walton NY, Kendrick C. A progressive sequence of electroencephalographic changes during generalized convulsive status epilepticus. Epilepsy Res. 1990;5:49–60. doi: 10.1016/0920-1211(90)90065-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turski L, Ikonomidou C, Turski WA, Bortolotto ZA, Cavalheiro EA. Review: cholinergic mechanisms and epileptogenesis. The seizures induced by pilocarpine: a novel experimental model of intractable epilepsy. Synapse. 1989;3:154–171. doi: 10.1002/syn.890030207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turski WA, Cavalheiro EA, Bortolotto ZA, Mello LM, Schwarz M, Turski L. Seizures produced by pilocarpine in mice: a behavioral, electroencephalographic and morphological analysis. Brain Res. 1984;321:237–253. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(84)90177-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]