Abstract

OBJECTIVE

The Cox-Maze IV procedure (CMPIV) has been established as the gold standard for surgical ablation, however late outcomes using current consensus definitions of treatment failure have not been well described. In order to compare to reported outcomes of catheter-based ablation, we report our institutional outcomes of patients who underwent a left-sided or biatrial CMPIV at five years of follow up.

METHODS

Between January 2002 and September 2014, data were collected prospectively on 576 patients with AF who underwent a CMPIV(n= 532) or left-sided CMPIV(n= 44). Perioperative variables and long-term freedom from AF on and off AADs were compared in multiple subgroups.

RESULTS

Follow up at any time point was 89%. At five years, overall freedom from AF was 78% (93/119) and freedom from AF off AADs was 66% (77/177). There were no differences in freedom from AF on or off AADs at 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 years between patients with paroxysmal AF(n=204) and patients with persistent/long-standing persistent AF(n=305), or between those who underwent stand-alone and those who received a concomitant CMP. Duration of preoperative AF and hospital length of stay were the best predictors of failure at 5 years.

CONCLUSIONS

The outcomes of the CMPIV remain good at late follow up. The type of preoperative AF or the addition of a concomitant procedure did not affect late success. The results of the CMPIV remain superior to those reported for catheter ablation and other forms of surgical AF ablation, especially for patients with persistent or long-standing AF.

Keywords: Atrial Fibrillation, Arrhythmia Therapy, Ablation

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

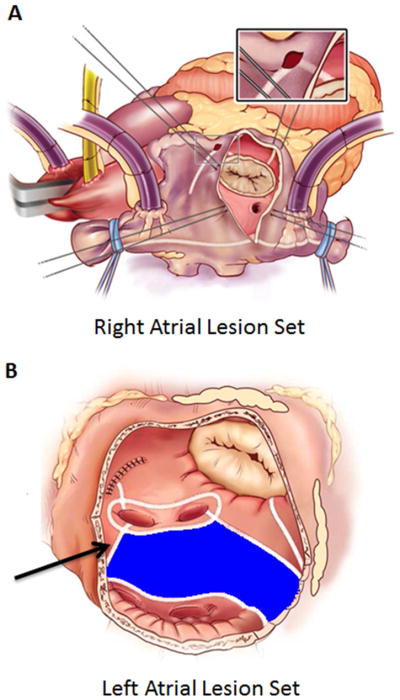

The first effective surgical treatment for atrial fibrillation, now formally known as the Cox-Maze procedure (CMP), was introduced by Dr. James Cox in 1987.1 On the basis of extensive clinical experience and ongoing animal investigations at our institution, significant revisions of the original “cut-and-sew” technique have led to the current, fourth iteration of the procedure. Introduced clinically in 2002, the Cox-Maze IV procedure (CMPIV) consists of a combination of bipolar radiofrequency (RF) and cryothermal ablation lines that replace the majority of the surgical incisions of its predecessor (Figure 1).2

Figure 1.

Standard right (A) and left (B) atrial lesions sets utilized for the Cox-Maze IV procedure. In the right atrium (A), radiofrequency (RF) ablation lines (white lines) extend from SVC to IVC and along the RA free wall down to tricuspid valve annulus. In the left atrium (B), all ablation lines are performed with a bipolar radiofrequency clamp except for an endocardial cryoablation at the mitral annulus and an epicardial cryoablation over the coronary sinus. Full isolation of the posterior left atrium (shaded blue) by creating a “box lesion” was accomplished by adding a superior connecting lesion (black arrow) joining the right and left circumferential pulmonary vein ablations. The box lesion was added to the CMPIV lesion set in 2005.25 Modified with permission from Weimar T, Bailey MS, Watanabe Y, et al. The Cox-maze IV procedure for lone atrial fibrillation: a single center experience in 100 consecutive patients. Journal of interventional cardiac electrophysiology : an international journal of arrhythmias and pacing. 2011;31:47–54.

Analysis of early and one-to-two year follow up have demonstrated that the CMPIV provided equivalent rates of freedom from AF and can be performed with shorter cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB) and cross-clamp times, and with less perioperative morbidity, than the traditional “cut-and-sew” Cox-Maze III procedure (CMPIII).2–5 Additionally, we have shown that the procedure is equally effective in patients undergoing ablation for lone AF and in those undergoing concomitant cardiac surgery, including coronary artery bypass grafting, mitral valve, and aortic valve procedures.6–11

The modifications of the CMPIV have allowed it to be performed through a right mini-thoracotomy (RMT) approach, which has further reduced major morbidity, mortality, and hospital stay compared to those who underwent sternotomy while enjoying equivalent outcomes with regards to freedom from AF.3, 4, 12 Finally, the CMPIV has proven to be effective in patients with both paroxysmal and non-paroxysmal (persistent and long-standing persistent) forms of AF, a quality that distinguishes the CMPIV from other less extensive lesion sets used for catheter and surgical AF ablation.13–16

Although our results to date have established the CMPIV as the current gold standard for surgical AF ablation, late outcomes of AF freedom using current consensus definitions of treatment failure have yet to be confirmed. Recent reports of long-term (>5 year) outcomes after the CMP have demonstrated good results17 while catheter ablation and pulmonary vein isolation have yielded suboptimal rates of freedom from AF in the majority of patients.15, 18–23 In this report, we examined our late outcomes of patients undergoing the Cox-Maze IV procedure for AF ablation at five years of follow-up.

METHODS

The Washington University School of Medicine Institutional Review Board approved this study, and written informed consent was obtained from each patient prior to enrollment. Over 400 demographic and perioperative variables were prospectively entered into the Society for Thoracic Surgery (STS) database or a longitudinal database maintained at our institution.

Patient Population

Between January 2002 and December 2014, data were collected prospectively on 576 consecutive patients with AF who underwent a CMPIV (n= 532) or left-sided CMP (n= 44) with or without a concomitant procedure. The operative details of the CMPIV lesion set through a sternotomy or right minithoracotomy has been previously described by our group.3, 5 In 2005, the CMPIV was modified to include a superior connecting lesion, which formed a “box lesion” by completely isolating the entire posterior left atrium (Figure 1).24, 25 Prior to 2005, patients underwent the original iteration of the CMPIV lesion set, which lacked a superior left atrial (LA) bipolar RF lesion connecting the right and left superior pulmonary veins.2 Of the patients who received a CMPIV, 89% (472/532) had a box lesion and 90% (40/44) of patients who received a left-sided CMP had a box lesion. Otherwise, patients who underwent a left-sided CMP had a complete CMPIV LA lesion set. Preoperative and perioperative variables were retrospectively evaluated and compared.

Follow up

Freedom from atrial tachyarrhythmias (ATAs) and freedom from antiarrhythmic drugs (AADs) at 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 years were evaluated by electrocardiogram (ECG) or prolonged monitoring by either 24-hour Holter monitor, pacemaker interrogation, or interrogation of implantable loop recorders as recommended by consensus guidelines.26 Success was defined as freedom from ATAs (AF, atrial flutter, or atrial tachycardia) after a 3-month blanking period as defined in the HRS/EHRA/ACAS consensus statements, and those with subsequent ablations were deemed permanent failures.26 Patients were discharged on class I or III AADs and warfarin for at least 2 months, unless contraindicated. AADs were discontinued after 2 months if the patient was in normal sinus rhythm and anticoagulation was discontinued at 3 months if prolonged monitoring showed no AF and there was no evidence of LA stasis on echocardiography. Calcium channel blockers and β-blockers were not considered as AADs.

Average follow up time was 3.3 ± 4.7 years. At 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 years following surgery, follow up was 84% (446/534), 67% (304/457), 58% (223/383), 55% (166/300), and 58% (139/241), respectively. Prolonged continuous monitoring was obtained in 67% (298/446), 66% (201/305), 63% (142/224), 57% (95/167), and 52% (72/139) at 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 years, respectively.

Freedom from ATAs and AADs

Late freedom from ATAs and AADs were compared between those who underwent a box lesion set (512/576) and those who did not (64/576). Those who did not undergo a box lesion were then excluded from the remainder of analyses. In the patients with a box lesion set (n= 512), long-term freedom from ATAs and AADs as well as selected preoperative and perioperative variables were compared between those patients with paroxysmal AF (n= 204) and those with persistent or long-standing persistent AF (n= 305). Most patients in both the paroxysmal and non-paroxysmal groups underwent concomitant procedures. Out of those who underwent concomitant procedures, 50% (206/408) underwent concomitant mitral valve procedure with or without a tricuspid procedure while 23% (93/408) underwent coronary artery bypass grafting with or without a mitral procedure (Supplement - Table 1). Late freedom from ATAs and AADs were also compared between those who underwent a stand-alone (n= 146) or concomitant CMPIV (n= 366).

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD) or as median with range and were compared using the t-test for means of normally distributed continuous variables and the Mann-Whitney U nonparametric test for skewed distributions. Categorical variables were expressed as frequencies and percentages with outcomes compared using the χ2 or the Fisher exact test. Twenty preoperative and perioperative variables were evaluated in a univariate analysis to identify potential predictors of late ATA recurrence or AAD use at 1 and 5 years. Significant covariates on univariate analysis (p ≤ 0.10) or covariates deemed clinically relevant based on our experience were entered into a multivariate binary logistic regression analysis and receiver operator curves were constructed. All data analyses were performed using SYSTAT 13 software (Systat Software, Inc., Chicago, IL).

RESULTS

Demographics

The mean overall age was 64 ± 12 years old, and 61% (351/576) of the population was male. Of the overall cohort, 41% (237/576) had paroxysmal AF and 58% (336/576) had non-paroxysmal AF, with 20% (66/336) persistent and 80% (270/336) long-standing persistent AF. Demographic data was compared between those with paroxysmal AF and those with non-paroxysmal AF (Supplement – Table 2). When compared to the paroxysmal AF group, the non-paroxysmal AF group of patients had a worse substrate of AF as indicated by a longer duration of preoperative AF (6.6 ± 6.8 vs. 4.9 ± 7.1 years, p=0.005), larger left atria (5.3 ± 1.1 vs. 5.0 ± 1.1 cm, p=0.006), and more failed catheter ablations (95/336 (28%) vs. 22/237 (9%), p<0.001).

Perioperative Results

Most patients underwent sternotomy in both the paroxysmal AF and non-paroxysmal AF groups (77% (182/237) and 81% (273/336), respectively, p=0.113; Supplement – Table 3) while the remaining patients underwent a right minithoracotomy as previously described.12 More patients underwent concomitant procedures in the paroxysmal compared to the non-paroxysmal AF group (81% (193/237) vs. 63% (212/336), p < 0.001; Supplement – Table 3). As expected, there were no differences between the two groups in 30-day mortality, postoperative pacemaker implantations, ICU length of stay, hospital length of stay, or most major complications. The paroxysmal group had a slightly higher rate of postoperative pneumonia (11% vs. 7%, p=0.04). In the non-paroxysmal group, 96% (293/305) underwent a biatrial CMPIV compared to 87% (178/204) of the paroxysmal group (p < 0.001), while all others underwent a left-sided CMPIV.

Freedom from ATAs and AADs

In the entire cohort including those who did and did not undergo box lesion sets (n= 576), the overall freedom from ATAs at 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 years was 92% (411/446), 88% (267/304), 87% (194/223), 81% (135/166), and 73% (102/139). Overall freedom from ATAs off AADs for the entire cohort at 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 years was 81% (357/440), 78% (231/298), 77% (164/213), 69% (110/160), and 61% (83/235). Freedom from anticoagulation at 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 years was 65% (286/440), 62% (184/296), 64% (136/213), 57% (92/161), and 55% (76/138), respectively.

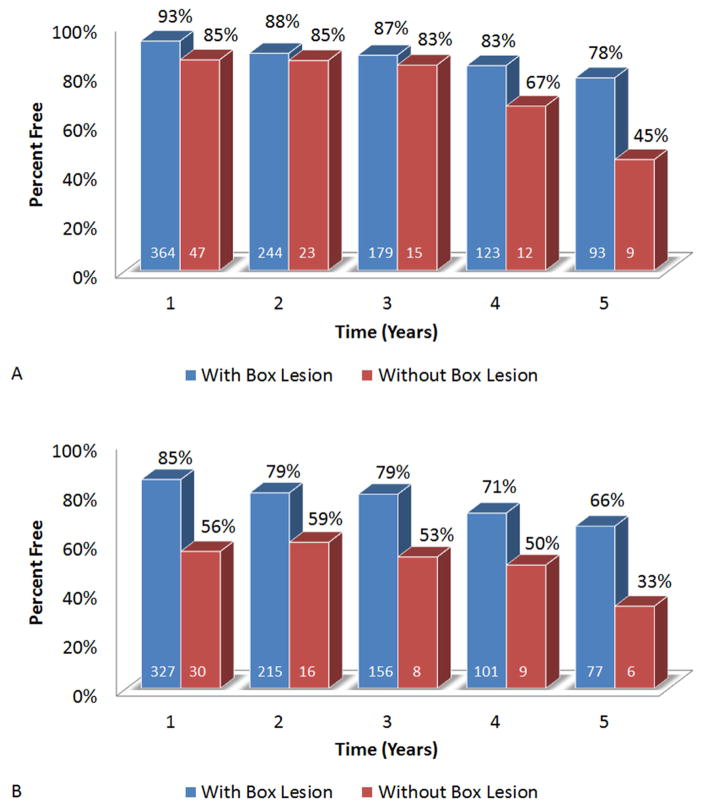

Lesion Set

Freedoms from ATAs on or off AADs were significantly higher in those who underwent box lesion sets when compared to those who did not at 5 years (78% (93/119) vs. 45% (9/20), p = 0.005; and 66% (77/117) vs. 33% (6/18), p = 0.017, respectively; Figure 2A+B). There was no significant difference in freedom from ATAs on or off AADs between the biatrial CMPIV lesion set and the left-sided CMPIV lesion set at 5 years (73% (95/130) vs. 78% (7/9), p = 0.758 and 62% (78/126) vs. 56% (5/9), p = 0.705, respectively). However, the number of left-sided CMPIV patients was small making any valid comparison difficult.

Figure 2.

Freedom from ATAs (A) and freedom from ATAs off of AADs (B) in patients who underwent full posterior left atrial isolation (box lesion) and those who did not.

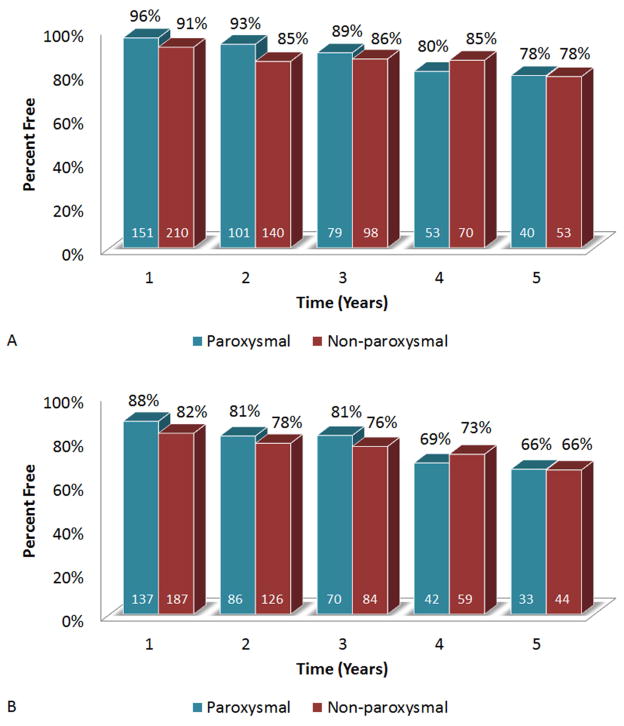

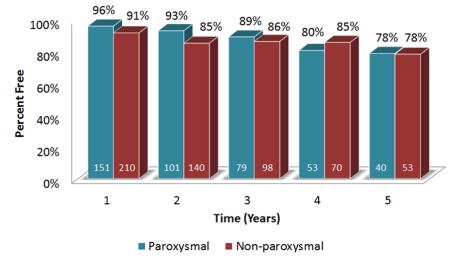

Paroxysmal vs. Non-paroxysmal AF

With those who did not undergo box lesion sets excluded, freedoms from ATAs at 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 years were not significantly different between those with paroxysmal vs. non-paroxysmal AF (96% (151/158) vs. 91% (210/230) at 1 year, p=0.105; 93% (101/109) vs. 85% (140/165) at 2 years, p = 0.051; 89% (79/89) vs. 86% (98/114) at 3 years, p=0.554; 80% (53/66) vs. 85% (70/82) at 4 years, p=0.414; and 78% (40/51) vs. 78% (53/68) at 5 years, p=0.97, respectively; Figure 3A). There were also no significant differences in freedoms from ATAs off AADs between the paroxysmal and non-paroxysmal AF groups at any time point (88% (137/156) vs. 82% (187/227) at 1 year, p=0.147; 81% (86/106) vs. 78% (126/162) at 2 years, p = 0.509; 81% (70/86) vs. 76% (84/110) at 3 years, p=0.394; 69% (42/51) vs. 73% (59/81) at 4 years, p=0.604; and 66% (33/50) vs. 66% (44/67) at 5 years, p=0.97, respectively; Figure 3B).

Figure 3.

Freedom from ATAs (A) and freedom from ATAs off of AADs (B) in patients with paroxysmal AF compared to those who had non-paroxysmal AF.

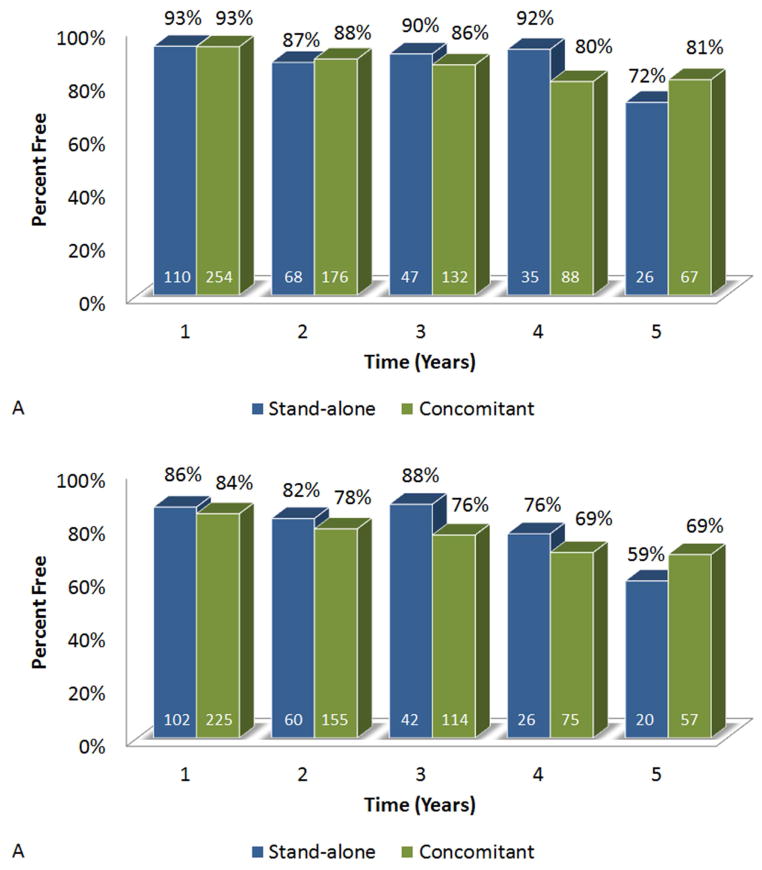

Stand-alone vs. Concomitant

There were no significant differences in freedoms from ATAs on or off AADs between those who underwent stand-alone CMPIV compared to those who underwent concomitant procedures at 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 years (Figure 4A+B).

Figure 4.

Freedom from ATAs (A) and freedom from ATAs off of AADs (B) in patients who underwent stand-alone CMPIV versus those who underwent a concomitant procedure.

Predictors of Recurrence

Univariate analyses of preoperative and perioperative variables were performed to determine predictors of late ATA recurrence or AAD use at 1 and 5 years. At 1 year, the absence of a box lesion, early ATAs, preoperative pacemaker implantation, and LA size were all predictive of recurrence (Table 4). In a multivariable binary logistic regression analysis, preoperative pacemaker (OR 2.492, 95% CI (1.351–4.599), p = 0.012), LA size (OR 1.285, 95% CI (1.022–1.615), p = 0.031), and the absence of a box lesion set (OR 4.556, 95% CI (2.364–8.780), p < 0.001) were predictive of ATA recurrence or AAD use at 1 year.

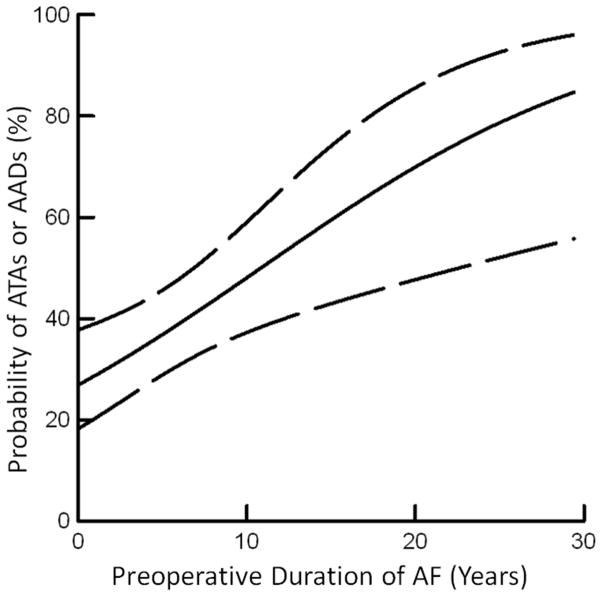

In the univariate analyses at 5 years, the absence of a box lesion, early ATAs, the duration of preoperative AF, total ICU time, overall complications, and hospital length of stay were all predictive of failure (Supplement – Table 4). In the multivariate analysis, the duration of preoperative AF (OR 1.09, 95% CI (1.02–1.16), p = 0.008) and hospital length of stay (OR 1.09, 95% CI (1.01–1.17), p = 0.026) predicted recurrence of ATAs or AAD use at 5 years. The probability of failure increased with increasing duration of preoperative AF (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Relationship between preoperative AF duration and the probability of ATA recurrence or AAD use at 5-year follow up.

DISCUSSION

Over the past 3 decades, the CMP has been the most successful surgical treatment for AF.5, 9, 27 In the current study, five-year outcomes of the newest iteration of the Cox-Maze procedure, the CMPIV, are reported. The major finding of the current study is that the CMPIV provided a high freedom from ATAs at late follow up. Moreover, the CMPIV was equally effective in patients with both paroxysmal and non-paroxysmal AF, and in patients undergoing both stand-alone and concomitant AF ablation procedures. The only predictors of late recurrence were duration of preoperative AF and hospital length of stay.

Our five-year results were consistent with the good early and midterm results of the CMPIV.5, 27 In patients receiving a complete lesion set our 5-year freedom from ATAs was 78% (93/119) and freedom from ATAs off AADs was 66% (77/177). In the only other study to report late outcomes of the CMPIV, Ad and colleagues demonstrated that 5-year freedom from ATAs was 85% and freedom from ATAs off AADs was 71% in a group of 120 patients. Their better results may be explained by the fact that their study population had a much shorter median duration of preoperative AF (27 months) compared to our study cohort (42 months).17 As we demonstrated in the present study, preoperative AF duration is an important predictor of late failure, and their freedom from ATAs was consistent with our calculated probability curves (Figure 5).

Our results compare favorably to two recent multi institutional trials that both showed 66% freedom from AF for the at only nine or 12 months follow up.28, 29 However, these studies did not have standardized ablation techniques and included institutions with variable amounts of experience with surgical ablation.

The CMPIV results in our series were better than what has been achieved with catheter ablation. In a study of 100 patients with mainly paroxysmal AF who underwent catheter ablation, the arrhythmia-free survival after a single ablation procedure was only 29% at 5 years. Allowing for multiple catheter ablations improved the arrhythmia-free survival since the last intervention to 63% at 5 years, with a median of two procedures per patient.23 Scherr and colleagues evaluated arrhythmia-free survival at five years for patients that underwent catheter ablation for persistent AF, which was the majority of patients in our study. In this study, 150 patients underwent catheter ablation and the five-year single procedure success was 17%.21 Several other large studies evaluating five-year success rates after catheter ablation have equally poor results.18, 20, 22 As a comparison to these studies, our data demonstrated 5-year freedom from ATAs of 78% from a single procedure.

Our results also compared favorably to other surgical lesion sets, in particular, pulmonary vein isolation. In a study of 139 patients who underwent minimally invasive surgical pulmonary vein isolation with up to five years of follow-up, freedom from AF off AADs was 52, 28, and 29% for paroxysmal, persistent, and long-standing persistent AF, respectively.15 This is consistent with other studies indicating that surgical pulmonary vein isolation might be more effective in patients with paroxysmal AF than persistent or long-standing persistent AF.19, 30 In contrast, our data and others have demonstrated that the CMPIV is equally effective in all groups of patients at both early and late follow-up.13, 17 The consistent efficacy of the CMPIV in non-paroxysmal AF is impressive in light of the worse substrate of AF in this group as indicated by the longer duration of preoperative AF, increased left atrial size, and a higher number of failed catheter ablations.

The success of the CMPIV in the concomitant setting is of equal importance considering that the majority of surgical ablations in the U.S. are performed as part of concomitant cardiac procedures.31 Our long-term results are consistent with early and midterm results, both from our institution and others, that have documented high rates of restoration of sinus rhythm with concomitant procedures including coronary artery bypass, mitral valve surgery, and aortic valve surgery.6–11 These data reinforce our belief that the CMPIV should be considered in all patients with AF undergoing concomitant cardiac surgery, as long as it can be performed without adding morbidity to the procedure.

This study identified several risk factors for recurrent ATAs by multivariate linear regression models at 1 and 5 years. At 1 year, left atrial size, preoperative pacemaker implantation, and the absence of a box lesion set were predictive of failure, which is consistent with previous studies from our group and others.16, 32–34 Interestingly, these variables were not predictors of failure at 5 years.17 In a recent report from Ad and colleagues, predictors of recurrence were left atrial size at two years and left atrial size, age, and length of hospital stay at 5 years. These inconsistencies suggest the possibility of different underlying pathophysiologic mechanisms of failure at different time points.

The duration of preoperative AF and length of hospital stay were both independent predictors of failure at 5 years. Duration of preoperative AF has been shown to predict late recurrence following both catheter and surgical ablation at 5 years in previous studies.17, 21, 35 This is likely due to the substrate remodeling that occurs with AF. In patients with a long duration of preoperative AF, this remodeling may not be reversible, and the CMP works poorly in this subgroup, particularly in patients with AF duration of longer than 11 years where success rates at 5-year follow up were less than 50%. Hospital length of stay is likely a marker of more underlying comorbidities, which could contribute to late failure.

Limitations

The success rates were reported for both the biatrial CMPIV and the left-sided CMPIV combined. The left-sided CMPIV lesion set was included in the analysis because the success rates were observed to be similar to that of the biatrial CMPIV. However, this was a highly selected group of patients. In our center, a left-sided CMPIV was chosen for patients with paroxysmal AF, LA size <5.0cm, and no evidence of right atrial enlargement. In this selected group, there was good late efficacy; however, comparisons with the biatrial CMPIV were not possible because of the limited number of patients available for late follow-up.

This was a retrospective, non-randomized study, which introduced confounding factors that may have affected our results. Incomplete follow-up and not universal continuous cardiac monitoring could potentially overestimate the actual freedom results. Also, the groups with paroxysmal and non-paroxysmal AF as well as patients who underwent stand-alone vs. concomitant procedures were inherently different making comparisons less than ideal. However, there were a large number of patients in our series, and the conclusions that the CMPIV works well for all groups is valid and undeniable. Since this was a single institutional study, these outcomes may not be obtainable at less experienced centers.

Conclusion

The CMPIV remains the most successful surgical treatment for AF, even in patients with non-paroxysmal AF and regardless of the complexity of the concomitant procedures. The duration of preoperative AF predicted failure at 5 years, and suggests the need for earlier intervention. Further follow up of this patient cohort is needed to determine whether there will be a further decrement in success over time.

Supplementary Material

PERSPECTIVE STATEMENT.

The CMPIV remains the most successful surgical treatment for AF, even in patients with non-paroxysmal AF and regardless of the complexity of the concomitant procedures. The duration of preoperative AF duration predicted failure at 5 years, and suggests the need for earlier intervention.

Acknowledgments

Supported by National Institute of Health grants R01 HL032257 and T32 HL007776. RJD receives research grants and educational funding from AtriCure and Edwards.

ABREVIATIONS

- AAD

antiarrhythmic drugs

- AF

atrial fibrillation

- ATA

atrial tachyarrhythmia

- CPB

cardiopulmonary bypass

- CMP

Cox-maze procedure

- CMPIII

Cox-maze III procedure

- CMPIV

Cox-maze IV procedure

- ECAS

European Cardiac Arrhythmia Society

- ECG

electrocardiogram

- EHRA

European Heart Rhythm Assocation

- HRS

Heart Rhythm Society

- IABP

intraaortic balloon pump

- ICU

intensive care unit

- LA

left atrial

- LOS

length of stay

- LVEF

left ventricular ejection fraction

- NYHA

New York Heart Association

- PVD

peripheral vascular disease

- SD

standard deviation

- RF

radiofrequency

- RMT

right mini-thoracotomy

- STS

Society of Thoracic Surgery

Footnotes

Presented at the American Association for Thoracic Surgery Annual Meeting, Seattle, WA, April 25–29, 2015

Conflict of Interest: All other authors have nothing to disclose.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Cox JL, Schuessler RB, D'Agostino HJ, Jr, et al. The surgical treatment of atrial fibrillation. III. Development of a definitive surgical procedure. The Journal of thoracic and cardiovascular surgery. 1991;101:569–583. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gaynor SL, Diodato MD, Prasad SM, et al. A prospective, single-center clinical trial of a modified Cox maze procedure with bipolar radiofrequency ablation. The Journal of thoracic and cardiovascular surgery. 2004;128:535–542. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2004.02.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Robertson JO, Saint LL, Leidenfrost JE, Damiano RJ., Jr Illustrated techniques for performing the Cox-Maze IV procedure through a right mini-thoracotomy. Annals of cardiothoracic surgery. 2014;3:105–116. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2225-319X.2013.12.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Saint LL, Lawrance CP, Leidenfrost JE, Robertson JO, Damiano RJ., Jr How I do it: minimally invasive Cox-Maze IV procedure. Annals of cardiothoracic surgery. 2014;3:117–119. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2225-319X.2013.12.01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weimar T, Schena S, Bailey MS, et al. The cox-maze procedure for lone atrial fibrillation: a single-center experience over 2 decades. Circulation. Arrhythmia and electrophysiology. 2012;5:8–14. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.111.963819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Henn MC, Lawrance CP, Sinn LA, et al. The Effectiveness of Surgical Ablation in Patients with Atrial Fibrillation and Aortic Valve Disease. The Annals of thoracic surgery. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2015.04.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ad N, Holmes SD, Massimiano PS, Pritchard G, Stone LE, Henry L. The effect of the Cox-maze procedure for atrial fibrillation concomitant to mitral and tricuspid valve surgery. The Journal of thoracic and cardiovascular surgery. 2013;146:1426–1434. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2013.08.013. discussion 1434–1425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Damiano RJ, Jr, Gaynor SL, Bailey M, et al. The long-term outcome of patients with coronary disease and atrial fibrillation undergoing the Cox maze procedure. The Journal of thoracic and cardiovascular surgery. 2003;126:2016–2021. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2003.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Prasad SM, Maniar HS, Camillo CJ, et al. The Cox maze III procedure for atrial fibrillation: long-term efficacy in patients undergoing lone versus concomitant procedures. The Journal of thoracic and cardiovascular surgery. 2003;126:1822–1828. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5223(03)01287-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Saint LL, Bailey MS, Prasad S, et al. Cox-Maze IV results for patients with lone atrial fibrillation versus concomitant mitral disease. The Annals of thoracic surgery. 2012;93:789–794. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2011.12.028. discussion 794–785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stulak JM, Sundt TM, 3rd, Dearani JA, Daly RC, Orsulak TA, Schaff HV. Ten-year experience with the Cox-maze procedure for atrial fibrillation: how do we define success? The Annals of thoracic surgery. 2007;83:1319–1324. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2006.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lawrance CP, Henn MC, Miller JR, et al. A minimally invasive Cox maze IV procedure is as effective as sternotomy while decreasing major morbidity and hospital stay. The Journal of thoracic and cardiovascular surgery. 2014;148:955–961. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2014.05.064. discussion 962–952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ad N, Henry L, Friehling T, Wish M, Holmes SD. Minimally invasive stand-alone Cox-maze procedure for patients with nonparoxysmal atrial fibrillation. The Annals of thoracic surgery. 2013;96:792–798. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2013.05.007. discussion 798–799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Boersma LV, Castella M, van Boven W, et al. Atrial fibrillation catheter ablation versus surgical ablation treatment (FAST): a 2-center randomized clinical trial. Circulation. 2012;125:23–30. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.074047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zheng S, Li Y, Han J, et al. Long-term results of a minimally invasive surgical pulmonary vein isolation and ganglionic plexi ablation for atrial fibrillation. PloS one. 2013;8:e79755. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0079755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Damiano RJ, Jr, Schwartz FH, Bailey MS, et al. The Cox maze IV procedure: predictors of late recurrence. The Journal of thoracic and cardiovascular surgery. 2011;141:113–121. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2010.08.067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ad N, Holmes SD, Stone LE, Pritchard G, Henry L. Rhythm course over 5 years following surgical ablation for atrial fibrillation. European journal of cardio-thoracic surgery : official journal of the European Association for Cardio-thoracic Surgery. 2015;47:52–58. doi: 10.1093/ejcts/ezu059. discussion 58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bunch TJ, May HT, Bair TL, et al. Five-Year Outcomes of Catheter Ablation in Patients with Atrial Fibrillation and Left Ventricular Systolic Dysfunction. Journal of cardiovascular electrophysiology. 2014 doi: 10.1111/jce.12602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.De Maat GE, Pozzoli A, Scholten MF, et al. Long-term results of surgical minimally invasive pulmonary vein isolation for paroxysmal lone atrial fibrillation. Europace : European pacing, arrhythmias, and cardiac electrophysiology : journal of the working groups on cardiac pacing, arrhythmias, and cardiac cellular electrophysiology of the European Society of Cardiology. 2015 doi: 10.1093/europace/euu287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ganesan AN, Shipp NJ, Brooks AG, et al. Long-term outcomes of catheter ablation of atrial fibrillation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of the American Heart Association. 2013;2:e004549. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.112.004549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Scherr D, Khairy P, Miyazaki S, et al. Five-year outcome of catheter ablation of persistent atrial fibrillation using termination of atrial fibrillation as a procedural endpoint. Circulation. Arrhythmia and electrophysiology. 2015;8:18–24. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.114.001943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schreiber D, Rostock T, Frohlich M, et al. Five-Year Follow Up after Catheter Ablation of Persistent Atrial Fibrillation using the “Stepwise Approach” and Prognostic Factors for Success. Circulation. Arrhythmia and electrophysiology. 2015 doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.114.001672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Weerasooriya R, Khairy P, Litalien J, et al. Catheter ablation for atrial fibrillation: are results maintained at 5 years of follow-up? Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2011;57:160–166. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.05.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Voeller RK, Bailey MS, Zierer A, et al. Isolating the entire posterior left atrium improves surgical outcomes after the Cox maze procedure. The Journal of thoracic and cardiovascular surgery. 2008;135:870–877. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2007.10.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Weimar T, Bailey MS, Watanabe Y, et al. The Cox-maze IV procedure for lone atrial fibrillation: a single center experience in 100 consecutive patients. Journal of interventional cardiac electrophysiology : an international journal of arrhythmias and pacing. 2011;31:47–54. doi: 10.1007/s10840-011-9547-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Calkins H, Kuck KH, Cappato R, et al. 2012 HRS/EHRA/ECAS expert consensus statement on catheter and surgical ablation of atrial fibrillation: recommendations for patient selection, procedural techniques, patient management and follow-up, definitions, endpoints, and research trial design: a report of the Heart Rhythm Society (HRS) Task Force on Catheter and Surgical Ablation of Atrial Fibrillation. Developed in partnership with the European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA), a registered branch of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Cardiac Arrhythmia Society (ECAS); and in collaboration with the American College of Cardiology (ACC), American Heart Association (AHA), the Asia Pacific Heart Rhythm Society (APHRS), and the Society of Thoracic Surgeons (STS). Endorsed by the governing bodies of the American College of Cardiology Foundation, the American Heart Association, the European Cardiac Arrhythmia Society, the European Heart Rhythm Association, the Society of Thoracic Surgeons, the Asia Pacific Heart Rhythm Society, and the Heart Rhythm Society. Heart rhythm : the official journal of the Heart Rhythm Society. 2012;9:632–696. e621. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2011.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Je HG, Shuman DJ, Ad N. A systematic review of minimally invasive surgical treatment for atrial fibrillation: a comparison of the Cox-Maze procedure, beating-heart epicardial ablation, and the hybrid procedure on safety and efficacydagger. European journal of cardio-thoracic surgery : official journal of the European Association for Cardio-thoracic Surgery. 2015 doi: 10.1093/ejcts/ezu536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Damiano RJ, Jr, Badhwar V, Acker MA, et al. The CURE-AF trial: a prospective, multicenter trial of irrigated radiofrequency ablation for the treatment of persistent atrial fibrillation during concomitant cardiac surgery. Heart rhythm : the official journal of the Heart Rhythm Society. 2014;11:39–45. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2013.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gillinov AM, Gelijns AC, Parides MK, et al. Surgical ablation of atrial fibrillation during mitral-valve surgery. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:1399–1409. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1500528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Edgerton JR, Edgerton ZJ, Weaver T, et al. Minimally invasive pulmonary vein isolation and partial autonomic denervation for surgical treatment of atrial fibrillation. The Annals of thoracic surgery. 2008;86:35–38. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2008.03.071. discussion 39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ad N, Suri RM, Gammie JS, Sheng S, O'Brien SM, Henry L. Surgical ablation of atrial fibrillation trends and outcomes in North America. The Journal of thoracic and cardiovascular surgery. 2012;144:1051–1060. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2012.07.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lawrance CP, Henn MC, Miller JR, Sinn LA, Schuessler RB, Damiano RJ., Jr Comparison of the stand-alone Cox-Maze IV procedure to the concomitant Cox-Maze IV and mitral valve procedure for atrial fibrillation. Annals of cardiothoracic surgery. 2014;3:55–61. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2225-319X.2013.12.09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gillinov AM, Sirak J, Blackstone EH, et al. The Cox maze procedure in mitral valve disease: predictors of recurrent atrial fibrillation. The Journal of thoracic and cardiovascular surgery. 2005;130:1653–1660. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2005.07.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ad N, Henry L, Holmes SD, Stone LE, Hunt S. The association between early atrial arrhythmia and long-term return to sinus rhythm for patients following the Cox maze procedure for atrial fibrillation. European journal of cardio-thoracic surgery : official journal of the European Association for Cardio-thoracic Surgery. 2013;44:295–300. doi: 10.1093/ejcts/ezs708. discussion 300–291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gaynor SL, Schuessler RB, Bailey MS, et al. Surgical treatment of atrial fibrillation: predictors of late recurrence. The Journal of thoracic and cardiovascular surgery. 2005;129:104–111. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2004.08.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.