Abstract

Area restrictions prohibiting people from entering drug scenes or areas where they were arrested are a common socio-legal mechanism employed to regulate the spatial practices of people who use drugs (PWUD). To explore how socio-spatial patterns stemming from area restrictions shape risk, harm, and health care access, qualitative interviews and mapping exercises were conducted with 24 PWUD with area restrictions in Vancouver, Canada. Area restrictions disrupted access to health and social resources (e.g., HIV care) concentrated in drug scenes, while territorial stigma prevented PWUD from accessing supports in other neighbourhoods. Rather than preventing involvement in drug-related activities, area restrictions displaced these activities to other locations and increased vulnerability to diverse risks and harms (e.g., unsafe drug use practices, violence). Given the harms stemming from area restrictions there is an urgent need to reconsider this socio-legal strategy.

Keywords: Area restrictions, drug users, qualitative research, qualitative GIS, territorial stigma

INTRODUCTION

Over the past several decades, advanced urban marginality has emerged as a defining feature of neoliberal urbanism, stemming in large part from growing income inequality, the retrenchment of social welfare, the expansion of the criminal justice system, and increased spatial segregation (Wacquant, 2008). This new regime of urban poverty has served to intensify territorial stigmatization in areas characterized as ‘slums’ or ‘ghettos’ (Wacquant, 2007; Wacquant, Slater, & Pereira, 2014). In this regard, territorial stigma illuminates how people living in these neighbourhoods are marked with a ‘blemish of place’ that functions to vilify them both within these neighbourhoods and through their engagements elsewhere, and thereby justifies their removal from urban space (Wacquant, 2007). This dynamic disproportionately impacts structurally vulnerable populations, variously including people who use drugs (PWUD), people who are homeless, and sex workers, whose marginalization within social hierarchies functions to render them vulnerable to suffering (Quesada, Hart, & Bourgois, 2011). Against this backdrop, municipalities have increasingly mobilized diverse mechanisms of urban social-spatial control toward the regulation and displacement of such structurally vulnerable populations, ranging from urban redevelopment initiatives (August, 2014; Kallin & Slater, 2014) to policing strategies (Wacquant, 2009).

Commonly referred to as ‘red zone’ orders in Canada and ‘stay out of drugs areas’ (SODA) or ‘stay out of areas of prostitution’ (SOAP) orders in the United States (Sylvestre, Bernier & Bellot, in press), area restrictions represent one such mechanism commonly employed to regulate structurally vulnerable populations, including PWUD (England, 2008), people who are homeless (Beckett & Herbert, 2009), and sex workers (Bruckert & Hannem, 2013). These restrictions prohibit people from entering designated drug or sex work scenes or areas where they have been arrested (Beckett & Herbert, 2009; Sylvestre, Bernier, & Bellot, in press). Although officially positioned as a preventative strategy to remove people from neighbourhoods where they might reoffend, area restrictions reinforce stigma by framing structurally vulnerable populations as ‘threats’ to be removed from urban space (Bruckert & Hannem, 2013).

There are several mechanisms that can be used to impose area restrictions. In the United States, ‘SODA’ and ‘SOAP’ orders can be imposed as part of community supervision conditions (i.e., pre-trial release conditions, conditional sentences, probation) for people arrested on drug or sex work-related charges (Beckett & Herbert, 2009; Sylvestre et al., in press). Many cities have also passed by-laws authorizing police officers or municipal officials to impose area restrictions on people alleged to have violated ‘civility laws’ (e.g., anti-camping ordinances, loitering in sex work zones), which can be issued without due process and are enforceable under criminal law (Beckett & Herbert, 2009). In Canada, ‘red zone’ orders can be imposed as part of ‘promise to appear’ orders issued by law enforcement officials to compel individuals released following arrest to appear in court, as well as part of community supervision conditions (e.g., bail or parole) (Sylvestre et al., in press). People caught by police violating their area restrictions (known as ‘breaching’) can face additional jail time or have their community supervision revoked.

Therein lies the complexity of area restrictions. As Beckett and Herbert (2009/2010) note, area restrictions occupy a unique position within the socio-legal landscape, in that they mobilize modernist and postmodern mechanisms of urban socio-spatial control. Following Foucault, area restrictions function as a form of ‘spatial governmentality’ that regulates structurally vulnerable populations by limiting their access to urban space (Beckett & Herbert, 2008). To this end, area restrictions operate alongside other forms of urban social control (e.g., surveillance cameras, neighbourhood watches) concerned with the socio-spatial regulation of structurally vulnerable populations, often to remove them from public view. However, because people violating area restrictions can be subject to arrest and incarceration, this form of spatial governmentality operates in conjunction with traditional forms of discipline intended to contain ‘deviant’ populations (Beckett & Herbert, 2008). Accordingly, area restrictions may be understood to be a hybrid socio-legal intervention that mobilizes the tools of the criminal justice system toward the exclusion, removal, and containment of the structurally vulnerable.

There are growing concerns regarding the potential of area restrictions to drive risk and harm among structurally vulnerable populations (Beckett & Herbert, 2009; Moser, 2001; Sylvestre et al., in press). Because these populations often rely on resources and services concentrated within drug and sex work scenes, measures that displace them have potentially dire consequences. Although limited, previous studies have suggested that having an area restriction is associated with difficulty accessing health and harm reduction services (Beckett & Herbert, 2009; Marshall et al., 2011; Shannon et al., 2009). Meanwhile, one study found that area restrictions adversely impacted the ability of sex workers to negotiate condom use (Shannon et al., 2009), while another found that they were associated with the initiation of high-risk drug use patterns (Marshall et al., 2011). Notwithstanding these insights, there remains a need to better understand how area restrictions function to shape risk, harm, and health care access, and how the displaced renegotiate urban space and survival against the backdrop of their structural vulnerability and territorial stigmatization.

These issues are of particular relevance in Vancouver, Canada’s Downtown Eastside neighbourhood, an approximately ten-block area that is home to the country’s largest drug scene and only supervised injection facility (Insite). This neighbourhood has been characterized in popular discourses as a metonym for urban disorder (Liu & Blomley, 2013), and may be understood to embody the stigma levied toward its inhabitants (Takahashi, 1997). The Downtown Eastside has historically been subjected to drug and sex work law enforcement strategies ranging from buy and bust schemes to police crackdowns (Csete & Cohen, 2003). Consistent with research undertaken in other settings (Aitken et al., 2002; Cooper et al., 2005; Maher & Dixon, 1999), these policing strategies have been found to foster drug-related risks (e.g., rushed injections, syringe-sharing) (Small et al., 2006; Werb et al., 2008; Wood, Kerr, et al., 2003) and displace PWUD and sex workers away from health and harm reduction services (Shannon et al., 2008; Wood, Kerr, et al., 2003). Although increasingly uncommon among sex workers following changes to law enforcement guidelines made following the deaths and disappearances of dozens of sex workers (McCann, Akin, & Airth, 2013), area restrictions continue to be deployed to manage PWUD in the Downtown Eastside and other drug scenes in the region.

We undertook this spatially oriented, qualitative study to explore how socio-spatial patterns stemming from area restrictions shape health and social outcomes among PWUD in the Downtown Eastside and elsewhere in Vancouver. We were particularly concerned with how changes to socio-spatial patterns influence access to health and social resources (e.g., health services, emergency accommodations) and engagement in drug scene activities (e.g., drug buying and selling). We also sought to understand the spatial tactics employed by PWUD to renegotiate survival following the receipt of area restrictions (including continued involvement in drug scene activity), and to locate their experiences within the broader context of territorial stigmatization.

METHODS

We undertook qualitative interviews and mapping exercises with 24 PWUD in Vancouver who had received area restrictions. Whereas experiences of ‘place’ are central determinants of health among drug-using populations (Tempalski & McQuie, 2009), we employed a spatially oriented qualitative approach to uncover how these evolving socio-spatial patterns influenced risk, harm, and health access by linking narrative data (qualitative interviews) with geospatial data (mapping exercises). This study was approved by the Providence Healthcare/University of British Columbia Research Ethics Board.

Most participants (n=22) were recruited from three ongoing prospective cohort studies comprised of drug-using populations: the Vancouver Injection Drug Users Study (VIDUS; HIV-negative), AIDS Care Cohort to Evaluate Exposure to Survival Services (ACCESS; HIV-positive), and At-Risk Youth Study Cohort (ARYS; street-involved youth). Cohort participants are recruited from storefront research offices located in the Downtown Eastside (VIDUS/ACCESS) and Downtown South (ARYS) neighbourhoods, and complete structured questionnaires and clinical assessments every six months (Strathdee et al., 1997; Wood, Montaner, et al., 2003; Wood, Stoltz, Montaner, & Kerr, 2006). We executed database queries to identify cohort participants who had answered “yes” to the following question during surveys completed within the previous two years: “Have you had any area restrictions (“red zones”) or outstanding warrants in the last 6 months?” Study personnel contacted potential participants, and screened out individuals with outstanding warrants only. Study personnel explained the study and scheduled interviews with those wishing to participate. The remaining participants (n=2) were recruited during an outreach visit to a drug user-led organization in a neighbouring city (Surrey, BC) conducted to reach PWUD displaced from Vancouver.

The lead author (McNeil) conducted the Vancouver-based interviews at the cohort study offices, and the Surrey-based interviews in a private room at a public library. Written informed consent was obtained prior to the interviews and participants received $20 honoraria. An interview topic guide was used to facilitate discussion regarding how area restrictions shaped socio-spatial patterns, and, in turn, drug-related risks, access to health services (including harm reduction programs), and involvement in drug scene activities, among other topics. Interviews were accompanied by qualitative mapping exercises during which the interviewer and participant documented their area restriction and the coordinates of key locations to their everyday spatial practices (e.g., drug dealing locations, health services). Interviews were audio recorded (25 to 70 minutes in length) and later transcribed.

We analyzed data by employing a computer-aided qualitative GIS approach involving techniques for interfacing narrative and geospatial data within NVivo, a qualitative data management and analysis software program, and ArcGIS, a geographic information software program (Jung, 2009; Jung & Elwood, 2010). Geo-spatial data from maps were imported into ArcGIS and used to produce digital maps, including aggregate maps depicting the distribution of area restrictions and individual maps of locations of importance prior to and following the receipt of area restrictions. Interview transcripts and maps were then imported into NVivo and coded by first drawing upon a coding framework made up of a priori codes extracted from the interview guide, which aimed to link participant accounts of their socio-spatial patterns to the mapping data. We regularly revised the coding framework to include emerging codes that reflected spatial dynamics and perceptions of area restrictions not represented in the initial coding framework. We then recoded the interview transcripts to determine the representativeness of these categories and revised our thematic descriptions accordingly. Finally, we drew upon the concept of territorial stigma when interpreting our findings to better understand social-structural forces that shaped the capacity of our participants to renegotiate the parameters of their daily lives following the receipt of area restrictions.

RESULTS

Sample Characteristics

Twenty-four individuals participated in this study, including twenty men and four women. Participants were an average of 37 years old (range 19–53 years). Our participants self-identified as Aboriginal (n=12) and White (n=12). All participants reported drug use in the thirty days prior to their interview, with crack cocaine (n=15), heroin (n=12), powdered cocaine (n=10), and crystal methamphetamine (n=9) reported as the most commonly used drugs. Most participants (n=20) had received area restrictions for non-violent offenses (e.g., drug trafficking, theft), while the remaining participants (n=4) were arrested for assault.

Suffering, consent, and intentions to comply with area restrictions

Experiences of ‘dopesickness’ (i.e., discomfort and pain associated with opiate withdrawal) and drug cravings motivated participants to ‘consent’ to area restrictions while seeking release from the criminal justice system despite concerns regarding potential impacts. The vast majority received area restrictions as pre-trial release conditions for non-violent offenses, such as shoplifting, possession of stolen property, and low-level drug dealing, primarily driven by extreme poverty and drug dependency. These participants reported being detained from six hours to up to two days (over the weekend) in jail for processing following arrest, enough time to experience the onset of dopesickness or drug cravings. The routine suffering that they experienced while detained fuelled the perception that “once you’re in that cell you’re forgotten… just [like] an animal in a cage.” Participants emphasized how discussions with police (promise to appear orders) or prosecutors/judges (bail or parole) occurred under duress. This limited their likelihood of voicing concerns regarding the potential impacts of area restrictions to police officers and judges, as well as consulting with legal counsel to challenge these orders on the basis that they would produce health risks and harms. Accordingly, most participants characterized the overall process as coercive because they believed that area restrictions were administered without due process or a clear understanding of potential consequences, while noting that the severity of their withdrawal symptoms or drug cravings meant that they “would have agreed to anything to get out.” For example:

[The withdrawal symptoms in jail were] like the worst flu I’ve ever had times ten…Combined with that, my pain was amplified. I was just walking around in constant pain. Couldn’t eat. Couldn’t sleep. Couldn’t get warm. Couldn’t be comfortable. I would’ve agreed to anything to get out as far as a ‘red zone’ goes…They’re putting a gun to our head when they’re asking us to agree, because “we’ll let you out if you agree…” What the fuck is that? […] They’re not being asked to agree to anything. They’re under duress. They can’t make a willful decision when they’re under duress. I think that it should be illegal because we’re supposed to be innocent until proven guilty. [Participant #9, White Man, 37 years old]

Despite these concerns, most participants initially intended to comply with these area restrictions to limit their likelihood of arrest for ‘breaching’ and thus short-term detention or the revocation of community supervision. Concerns that they would again experience the suffering associated with withdrawal or drug cravings in jail shaped participants’ views of area restrictions. One participant who had experienced severe opiate withdrawal in the municipal jail explained:

I couldn’t do the things I normally would do and had to go out of my way to go wherever I needed to go. Had to go around my red zone, you know, thinking all the time that if I got caught in my red zone that I would go back to jail. [Participant #14, White Man, 44 years old]

Understanding displacement: exclusion, containment, and gentrification

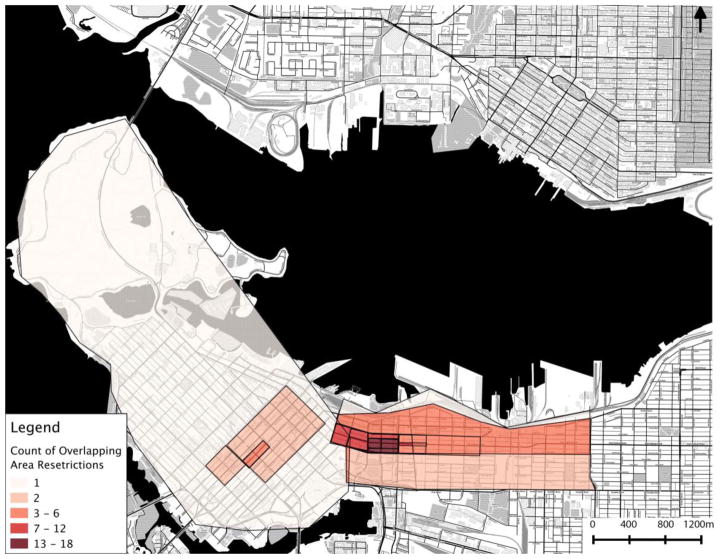

Participants’ socio-spatial patterns prior to arrest/incarceration were shaped by their need to negotiate survival and drug dependence within the context of their structural vulnerability. These socio-spatial patterns largely revolved around resources (e.g., health and harm reduction services, prime drug dealing locations) concentrated in drug scene areas, which they were generally restricted from occupying upon receiving area restrictions. Figure 1 depicts the distribution of area restrictions received by participants, which were concentrated in areas in the Downtown Eastside. The area restrictions depicted on this map encompass key health and social supports (e.g., supervised injection facility, syringe exchange services), and prime drug dealing and street vending locations. Although two participants received ‘micro’ area restrictions in commercial areas with minimal potential to disrupt their spatial patterns (i.e., bans from specific blocks), the remaining participants were similarly prohibited from resource rich drug scene areas elsewhere in the Vancouver-area.

Figure 1.

Distribution of area restrictions among study participants

Participants considered their area restrictions to be “unfair” or “bullshit” because of the hardships imposed by disruptions to their spatial patterns (e.g., access to resources, income-generating opportunities). Participants articulated three key dimensions of displacement. First, participants expressed that being displaced from the Downtown Eastside would require them to seek out resources and supports (e.g., health services, food programs) in other parts of the city. Further, participants emphasized that territorial stigma functioned to mark “people from the Downtown Eastside” as a ‘blemish’ to be removed from these parts of the city. As a consequence, they were unwelcome in other neighbourhoods, as well as subjected to surveillance and harassment. For example, one participant explained how he felt unsafe in other neighbourhoods because of how “people from the Downtown Eastside” are treated:

Once I leave the Downtown Eastside, I have to be careful and protective… I [have] been stopped by the police two three times ‘cause they want to check you out…Some people down there [i.e., upscale neighbourhood adjacent to the Downtown Eastside] don’t like [us]… There’s some violent people down there. I had to walk away from a potentially violent situation because there was some young drunk people that started to really mouth off at me. [Participant #1, White Man, 50 years old]

Second, because the Downtown Eastside was, in many cases, the only neighbourhood where they felt welcome and could access supports and resources, participants emphasized how they would have to risk arrest in order to survive. This was perceived as a central contradiction of area restrictions. While area restrictions functioned as a mechanism to displace participants from drug scene areas (e.g., Downtown Eastside), social-structural forces (e.g., territorial stigmatization, policing) simultaneously functioned to contain them, either within specific areas or through the criminal justice system. The following interview excerpts illustrate how participants viewed area restrictions as a mechanism to simultaneously displace and contain them:

A guy that’s living down here has limited resources already and to remove those resources from somebody… That could really make things tough for a guy. What will that do? It may force him out of the neighbourhood and into a neighbourhood they don’t really want him in… If they’re behaving like they do down by the Bottle Depot [prime drug market location] out in Kitsilano [expensive residential neighbourhood], I’m sure that’s not going to be well received. [Participant #6, Aboriginal Man, 47 years old]

I don’t know where they expect them to go. I mean, they give you a red zone, it’s pretty much bait. It’s just setting you up for failure. If you’re an addict, you’re an addict, right? If an addict needs to get some drugs and that’s the place that the drugs are and it’s all well known, then you’re just setting somebody up for jail. [Participant #14, White Man, 44 years old]

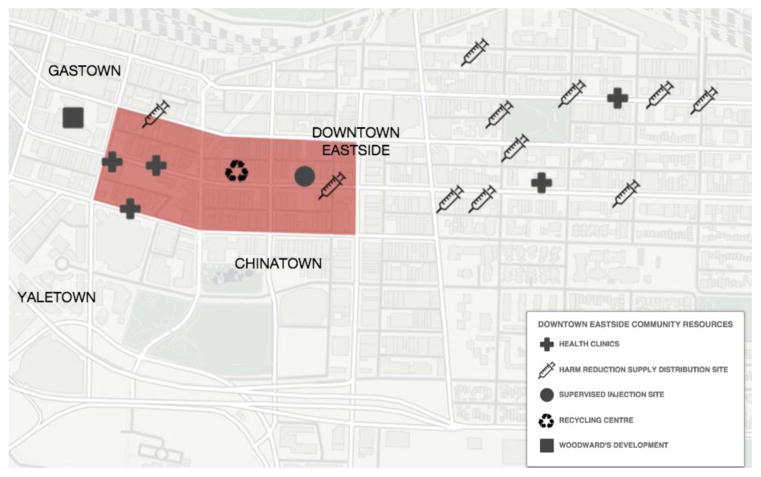

Third, our participants linked the displacement and containment resulting from area restrictions to broader efforts to ‘sanitize’ urban space through the removal of structurally vulnerable populations. Notably, many participants articulated how efforts to displace them were part of a larger socio-political agenda driven by the imperative to minimize perceived disorder in commercial areas (Downtown South) and create more favourable conditions for gentrification (Downtown Eastside). It is worth noting that the Downtown Eastside is rapidly gentrifying and the area that participants were most often banned from (Figure 2) is located next to a $400 million mixed use development (Woodward’s Building) and serves as a corridor connecting an upscale neighbourhood (Yaletown) to tourist areas (Chinatown and Gastown) (Small et al., 2012). Although area restrictions have been employed pursuant to the socio-spatial control of drug-using populations for decades, participants linked their area restrictions to the intensification of gentrification in the Downtown Eastside. For example:

The way they deal with it [i.e., area restrictions] is kinda like a roundabout way. ‘Let’s just push them all [out of] the area.’ ‘Let’s just take away these buildings.’ […] That’s what’s gonna happen to these [single room occupancy] hotels. They’re gonna condemn ‘em ‘cause they’re so old… They’re gonna raze ‘em and, six months later, you’re gonna have your five hundred thousand dollar condos. That’s what’s gonna happen to the Downtown Eastside. That’s the way they do it. Let’s just gentrify the neighborhood…We’re just gonna take it away from them [i.e., PWUD]. [Participant #3, Aboriginal Man, 37 years old]

Figure 2.

Distribution of community resources within the epicenter of participant area restrictions

Disruptions in access to health resources & social supports

Participant accounts highlighted how changes to spatial practices associated with compliance with area restrictions increased suffering and social exclusion by compromising access to health and social supports. These disruptions were particularly pronounced in the periods immediately following the receipt of area restrictions, when concerns regarding arrest led to rigid compliance and the avoidance of services concentrated within drug scenes. Several participants described how area restrictions interrupted their access to social resources, such as low-income housing or emergency accommodations, which, in turn, disrupted income generating strategies and routine drug use patterns (e.g., access to regular dealer and drug use settings) that had enabled them to reliably manage withdrawal symptoms. While participants emphasized how these disruptions were ineffective in reducing drug use in the long-term, they functioned to increase suffering in the short-term. For instance, one participant who had been staying in an emergency shelter described the agonizing withdrawal symptoms that he experienced when his drug use patterns were disrupted upon being barred from the entire Downtown Eastside and subsequently becoming street homeless when unable to obtain accommodations elsewhere:

I took myself off the street, and found a place to roll up until morning because all the police know me and, if I was seen walking around, they would’ve arrested me…There were just different places that I slept outside, like at the park…For those [first] few days, I made sure that I was out of sight, out of mind…The pain [due to withdrawal] it sucks the life right out of you. I felt really alone and destitute at that time. [Participant #9, White Man, 37 years old]

In addition, participants underscored how the harms stemming from area restrictions increased over time due to the cumulative impacts of reduced access to usual sources of health and social supports (e.g., emergency shelters, housing, HIV care). Importantly, participants expressed that they were excluded from services elsewhere in the city as a function of territorial stigma, in that their status as “addicts” from the Downtown Eastside or other drug scenes served to reinforce their subjugation within or exclusion from mainstream health and social care settings (e.g., hospitals, clinics). In turn, area restrictions that prohibited participants from accessing usual sources of health and social support had the dual effect of interrupting treatment regimens (including HIV treatment) and undermining access to resources critical to maintaining health. For example:

They’re not taking into account the fact that [HIV care facility] is the only place for a lot of us to receive the care that we can’t get other places… I have to go there every two months and get my anti-retrovirals. I go there three [or] four times a week just to sit and hang out with people… Being a drug addict, I don’t have any friends… I have people that like to use drugs with me but, once the drugs are gone, so are they. It’s nice to have somebody who doesn’t care about that…[Access to free meals] was eliminated…I got down to 140 pounds at that time… I started borrowing a lot more money from people to eat. [Participant #2, Aboriginal Man, 39 years old]

It fucks so many things up…I only took it seriously because I was with my girlfriend and didn’t want either of us to go to jail…Faced difficulty ‘cause I had, like, appointments [youth services centre within his area restriction]. I was setting up with housing and shit [prior to being arrested]…I don’t know how serious it was if I got caught [at the youth services centre], so I never did [follow up on housing referrals]. [Participant #12, White Man, 19 years old]

Meanwhile, many participants expressed concern regarding the loss of relationships with care providers as a result of their area restrictions, many of which were their only positive relationships. These participants described how these relationships had facilitated positive life changes that had increased social inclusion, and how these were negatively impacted by area restrictions. For example:

That’s all my positive contacts you know. It’s who you know for employment and everything else. I used to work for the [social housing organization]. That’s where they’re housed also and I had to access that and a lot of volunteer programs are down in there that I used to do and couldn’t go to them. [Participant #14, White Man, 44 years old]

Renegotiating drug scene involvement and exposure to risk and harm

Area restrictions functioned in the short term to displace drug use and drug scene activities to other locations in the Downtown Eastside or outlying areas while forcing participants to renegotiate their parameters, which interfered with their ability to enact risk reduction and increased vulnerability to violence. Despite the widespread availability of harm reduction supplies in the Downtown Eastside, some participants nonetheless indicated that area restrictions constrained their access to these supplies by disrupting drug use routines. Although no participants reported syringe sharing, they reported engaging in other high-risk drug use practices. For example:

It’s just difficult ‘cause the needle depot is the supplier of pipes for me and they’re in my red zone. So for me to go there, it’s taking a chance and that’s not worth it…So then I end up using an old pipe or having to borrow one…That’s a risk on another level. [Participant #14, White Man, 44 years old]

Among participants whose restrictions encompassed areas where they normally purchased or consumed drugs, compliance required the re-negotiation of these activities. Many participants reported purchasing drugs from new drug dealers, which sometimes led to changes in the dynamics of these transactions (e.g., drug debts). Meanwhile, other participants were unable to access private or regulated drug use settings (e.g., supervised injection facility), and thus were pushed into high-risk public drug use settings. The following excerpts illustrate how these changes to their usual drug use patterns increased the risk of violence:

I feel less safe out here because I don’t know a lot of people…A few people I’ve had problems with over money, debts for drugs… I owe twenty dollars for a rock [i.e., crack cocaine] that I had [borrowed] before payday. Soon as I went broke, she showed up [to collect]… I had a fight and I stood up for myself but the woman had a knife… I’ve had quite the struggle to survive out here. [Participant #21, Aboriginal Woman, age not reported]

[Injecting in an alleyways] was awful… I was a lot more afraid for my safety…There was one time I had to stop an injection midway and pull out a knife because I saw these two guys were hanging around [and] they kept looking over at me. It was obvious they were they were trying to build up their courage to dummy [i.e., rob] me…They had seen me make a purchase. I was stupid I had pulled out my whole wad and pulled off a few twenties to make the purchase…So, I stopped what I was doing midway, which is not something an addict is used to doing when it comes to injecting… I’m in that much danger – I felt I was. I literally had to pull out a big knife and look at them and smile and say, “Bring it on boys.” [Participant #2, Aboriginal Man, 39 years old]

Among participants arrested for low-level drug dealing to support their drug dependence, area restrictions were poorly positioned to reduce involvement in this activity, which was one of the only income-generating opportunities available to them. These participants simply moved their drug dealing activities elsewhere in the neighbourhood. However, the systemic violence that characterizes drug dealing in these settings (McNeil et al., 2014; Small et al., 2013) meant that they incurred significant risk (e.g., police harassment, violence) in negotiating these environments. For example:

I have [been selling drugs] once again, not in that area… I just go a little ways away ‘cause the way that they sell out there is they stand there - the main drug dealers and they’re the ones that are known. Not the workers obviously. They are [pause] recognized… It’s all compacted into these few blocks. The police are always around, so people are scared… [Participant #23, White Man, 55 years old]

Resistance, subversion, and the right to survival

Nearly all participants articulated how they came to view area restrictions as “hazardous” due to the severe harms stemming from compliance and expressed that they ultimately “had no choice” but to eventually breach these release conditions. Non-compliance with area restrictions may be understood to be a ‘rational choice’ due to the hardships stemming from displacement. Some participants also positioned non-compliance as an act of resistance to social-structural forces (e.g., criminalization of drug use, gentrification) that functioned to displace them from neighbourhoods that they identified as theirs. These participants spoke of how they challenged the authority of the criminal justice system by actively reclaiming space and asserting their right to survival in the city. As one participant explained:

Just fuckin’ forget about it. I’m not going to let nobody tell me what I can and cannot do. I [have] been down here [i.e., Downtown Eastside], I [have] been traveling around on this side of town since I got released…There’s nothing really preventing me from like traveling back and forth…I made that clear right in court. There’s no chance in hell I’m going to follow that [area restriction]. [Participant #7, Aboriginal Man, 27 years old]

Among these participants, area restrictions were considered to be orders that were routinely challenged through non-compliance, with one participant noting, “everybody I that I know with a red zone, they still go to their red zone.”

While those participants challenging the authority of area restrictions simply returned to prior spatial patterns, many participants subverted their area restrictions by enacting strategies to decrease their likelihood of arrest for ‘breaching’. Participants commonly articulated how they made changes to their physical appearance to avoid being recognized by police officers. For example:

I would always wear a hoodie. I would wear sunglasses, tie my hair up, y’know…just kind of incognito. It helped, it really did because I remember seeing cops just look at me and it’s funny ‘cause I’m such a talkative and outgoing person that the cops know me…They don’t recognize me. [Participant #13, Aboriginal Woman, 21 years old]

Meanwhile, other participants adopted spatial tactics (e.g., taking new routes) that enabled them to avoid police or reflected a more nuanced interpretation of the parameters of their area restrictions. For example, one participant described how he employed spatial tactics to reclaim space and access supports after receiving an area restriction encompassing key areas within the Downtown Eastside. His area restriction constrained access to harm reduction supplies and a major recycling centre located within the most commonly restricted area in the Downtown Eastside, which was an important income source for him as well as other participants. As a result of the diverse harms stemming from compliance with his area restriction (e.g., weight loss, reduced income, drug-related risks), this participant subverted his area restriction by moving through alleyways rather than the street:

They didn’t say anything about the alleys, so I assumed I was allowed in the alley…[After receiving area restrictions] I started going down by Science World taking my recycling down to Terminal…I carried everything [recyclables] and, when I get a heavy load, man [it was] taking a lot outta [me]… I had to totally change my route and that was a long walk. You know, as a result of that, I lost so much weight [due to increased activity and less income for food]… When I started going to the back door at the bottle depot [through the alley], they were accommodating me. But then, I started violating because I started buying off my same guy I always used to buy off of [within his area restriction]. I was always very careful and got away with it. [Participant #1, White Man, 50 years old]

In this regard, the transgressive actions of participants to avoid detection by police (e.g., altering their appearance, changing their routes) were not intended to overturn the authority of the criminal justice system (DeVerteuil, Marr & Snow, 2009), but instead represented an adaptive survival strategy that responded to the hardships imposed by area restrictions. Nonetheless, our analysis of participant accounts underscored how these resistances and transgressions were insufficient in avoiding further punishment. Approximately one third reported that they had at some point been arrested for breaching their release conditions. These arrests stemmed from encounters with police as a consequence of prejudicial policing or public nuisance offences that resulted in warrant searches, even in situations where area restrictions were the participant’s only outstanding legal issue. In turn, participant narratives illustrated how area restrictions functioned to “keep’em in the system” – that is, to prolong their engagement with the criminal justice system. For example:

The cop recognized me and pulled over and he’s like, “You’re breaching your red zone.” And, he arrested me…They brought me in. I had to see a judge and they released me ‘cause at the time I didn’t have any charges or anything…All of a sudden, now I’m getting charged for the breach…It’s just breaching your probation or your bail…And, you have to go to court. [Participant #8, Aboriginal Man, 25 years old]

DISCUSSION

In summary, we found that participants were initially motivated to comply with area restrictions to avoid incarceration and withdrawal, and positioned area restrictions as a mechanism of urban socio-spatial control intended to displace them from gentrifying neighbourhoods or commercial areas. The subsequent disruptions in access to health and social resources (e.g., HIV care) produced diverse risks and harms (e.g., HIV treatment interruptions), owing in part to the barriers to accessing resources elsewhere due to territorial stigmatization. Meanwhile, rather than discouraging engagement in drug scene activities, area restrictions led participants to renegotiate their parameters (e.g., drug buying or selling), and increased their exposure to drug-related risks and violence. We found that the severe harms stemming from area restrictions led participants to ignore these orders and enact diverse spatial tactics to reclaim their right to urban space and survival, which were often unsuccessful and led to arrest and incarceration.

Building upon previous research on conventional spatial policing strategies (e.g., police crackdowns) (Cooper et al., 2005; Maher & Dixon, 1999; Small et al., 2006), our findings demonstrate how area restrictions increased vulnerability to health risks and harms among PWUD. Accordingly, our findings are consistent with the large body of research outlining how drug law enforcement is a key structural driver of risk, harm, and health access among PWUD (Kerr, Small, & Wood, 2005; McNeil & Small, 2014). However, our findings suggest that area restrictions may be distinct from more conventional spatial policing strategies in shaping risk, harm, and health care access even in the absence of law enforcement officers. Because PWUD rely upon resources concentrated within drug scenes, their displacement from these areas has the cascading effect of disrupting strategies that enable them to negotiate health and safety within the broader context of their structural vulnerability, and thereby fostering diverse risks and harms (e.g., treatment interruptions, unsafe drug use practices). For example, some participants were unable to access harm reduction supports located within the Downtown Eastside following the receipt of area restrictions and subsequently engaged in high-risk drug use practices, raising concerns about the potential of area restrictions to contribute to the transmission of HIV and Hepatitis C.

Our findings also underscore how it simply might not be possible for PWUD to access resources outside of stigmatized neighbourhoods due to territorial stigmatization. Although territorial stigmatization has been advanced as a mechanism for understanding how the spatial segregation of structurally vulnerable populations produces health inequities (Keene & Padilla, 2014), this work represents one of few empirical studies to outline how it constrains access to resources, and the consequences of this for health risks and harms. Consistent with previous studies outlining how territorial stigma follows structurally vulnerable populations to contribute to their marginalization by limiting access to resources in other neighbourhoods (e.g., housing, employment opportunities) (Keene & Padilla, 2010; McCormick, Joseph, & Chaskin, 2012; Wacquant, 2008), our findings demonstrate how this exclusionary function extends to health services. Despite not being able to access usual sources of support (inclusive of harm reduction programs) when complying with area restrictions, which impacted their health, our participants remained largely unwilling to access these supports elsewhere due to concerns about facing discrimination associated with being from a stigmatized neighbourhood. Serious concerns regarding the significant public health impacts of area restrictions should weigh into legal discussions pertaining to community supervision requirements, and these measures should only be pursued in rare circumstances (i.e., when someone poses an immediate physical threat to someone in that area) to avoid imposing punishment that compromises health and wellbeing.

Moreover, our findings underscore how area restrictions were largely ineffective in achieving their stated goal – that is, preventing PWUD from engaging in drug-related crime – and instead simply moved drug-related activities to other areas and made them less safe. We found that the renegotiation of drug-related activities following displacement to other areas in the drug scene increased public drug use and exposure to violence while compromising the ability of PWUD to enact risk reduction, echoing similar findings from studies of the impacts of street policing practices undertaken elsewhere (Cooper et al., 2003; Small et al., 2006; Taylor & Brownstein, 2003). Our findings thus build upon previous research illustrating how structural violence embedded within law enforcement practices (in this case, area restrictions) frames the interpersonal violence experienced by drug-using populations (McNeil, Kerr, Lampkin & Small, 2015; Sarang et al., 2010), and how this is intertwined with health and specific places (in this case, ‘new’ drug scene areas) (DeVerteuil, 2015). Meanwhile, we found that participants arrested for low-level drug dealing to support drug dependence simply relocated to other areas. The continued involvement of PWUD in drug-related activities raises doubts about the merits of area restrictions as a preventative measure, echoing similar findings from a study undertaken in the United States (Beckett & Herbert, 2009). Mounting evidence that spatial policing strategies simply displace drug-related activities and increase vulnerability to harm only further points to the urgent need to abandon these approaches in most situations and pursue alternatives to aggressive drug law enforcement.

The consequences of area restrictions necessarily beg the question as to what exactly these orders serve to accomplish. Consistent with research on other mechanisms of urban socio-spatial control (Mitchell & Heynen, 2009; Smith, 1996), our findings suggest that area restrictions may serve to remove structurally vulnerable populations from urban neighbourhoods that are undergoing gentrification insofar as these orders were clustered close to urban redevelopment projects. This perceived function of area restrictions featured prominently in participant narratives, fuelling concerns that they would be permanently displaced from one of the only neighbourhoods (Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside) where they could negotiate survival and motivating non-compliance with these orders. A recent study undertaken in the United States similarly documented high levels of non-compliance with area restrictions, focusing on how non-compliance was necessary due to the harms stemming from area restrictions (Beckett & Herbert, 2009). While we similarly found that non-compliance with area restrictions represented a rational choice due to the severity of these harms, our findings also point to how non-compliance was positioned by individual participants as an act of resistance through which they asserted their right to space and survival in the city. Against the backdrop of mechanisms of urban socio-spatial control that ‘annihilate’ the spaces that the structurally vulnerable can occupy (Mitchell, 2003), such resistance underscores the high stakes of neoliberal urbanism. In the Downtown Eastside, as elsewhere, PWUD, among other populations, increasingly find themselves ‘out of place’, and forms of resistance, ranging from non-compliance to community and legal advocacy, may be the only mechanisms through which they can counter these social-structural forces to claim a right to the city.

This study has several limitations. First, despite conducting outreach to reach individuals displaced from the Downtown Eastside, we encountered difficulty in recruiting such individuals and our findings are unlikely to account for their experiences. Second, women and transgender persons were underrepresented among our sample and further research is needed to understand gendered dynamics of area restrictions. Third, we were unable to employ more complex data visualization strategies (e.g., time-space prisms) due to limitations of our data. Additional studies deploying such methods remain needed to further highlight the spatial dynamics of area restriction. Fourth, our study did not focus on documenting organized resistance (e.g., NIMBYism) to the displacement of PWUD from drug scenes, and additional work is needed to explore this potential phenomenon. Fifth, our study was undertaken in a setting where police have exercised considerable albeit inconsistent discretion in drug law enforcement (DeBeck et al., 2008), and research undertaken in settings where such laws are more vigorously enforced might yield different results. Finally, as in inner city neighbourhoods elsewhere, programs and policies that accommodate drug-using populations in Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside (e.g., supervised injection facility, emergency accommodations) operate alongside others, such as area restrictions, intended to remove them from urban space. Future research might consider the tensions between these approaches, with particular attention to the limits or contradictions of ‘accommodative’ approaches (see, for example, Boyd & Kerr, in press; McNeil, Small, Lampkin, Shannon & Kerr, 2014).

In conclusion, our study illustrates how area restrictions not only functioned to increase exposure to risk and harm among drug-using populations, but also were largely unsuccessful in preventing involvement in drug-related activities. In turn, our findings highlight the need to reconsider this approach to the management of drug-using populations and instead embrace evidence-based interventions that address the underlying causes of perceived drug-related disorder (e.g., poverty, drug dependence) and promote social equality and spatial inclusion.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the study participants for their contributions to this research. We thank Will Damon for his assistance creating maps. We thank Tricia Collingham, Cameron Dilworth, William Lee, Jenny Matthews, Kristie Starr, and Guido Thylmann for the research and administrative assistance. This study was supported by the US National Institutes of Health (R01DA033147, R01DA011591, and R01DA021525). Ryan McNeil and Will Small are supported by the Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: None

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Aitken C, Moore D, Higgs P, Kelsall J, Kerger M. The impact of a police crackdown on a street drug scene: evidence from the street. International Journal of Drug Policy. 2002;13(3):193–202. [Google Scholar]

- August M. Negotiating social mix in Toronto’s first public housing redevelopment: power, space and social control in Don Mount Court. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research. 2014;38(4):1160–1180. [Google Scholar]

- Beckett K, Herbert S. Dealing with disorder: Social control in the post-industrial city. Theoretical Criminology. 2008;12(1):5–30. [Google Scholar]

- Beckett K, Herbert S. Banished: the new social control in urban America. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Boyd J, Kerr T. Policing ‘Vancouver’s mental health crisis’: a critical discourse analysis. Critical Public Health. doi: 10.1080/09581596.2015.1007923. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruckert C, Hannem S. To serve and protect? Structural stigma, social pro ling, and the abuse of police power in Ottawa. In: Van der Meulen E, Durisin EM, Love V, editors. Selling sex: Experience, advocacy, and research on sex work in Canada. Vancouver, BC: UBC Press; 2013. pp. 297–313. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper H, Moore L, Gruskin S, Krieger N. The impact of a police drug crackdown on drug injectors’ ability to practice harm reduction: A qualitative study. Social Science & Medicine. 2005;61(3):673–684. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.12.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Csete J, Cohen J. Abusing the user: police misconduct, harm reduction and HIV/AIDS in Vancouver. Human Rights Watch. 2003;15(2B):1–28. [Google Scholar]

- DeBeck K, Wood E, Zhang R, Tyndall M, Montaner J, Kerr T. Police and public health partnerships: Evidence from the evaluation of Vancouver’s supervised injection facility. Substance Abuse Treatment, Prevention, and Policy. 2008;3(1):11. doi: 10.1186/1747-597X-3-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeVerteuil G. Conceptualizing violence for health and medical geography. Social Science & Medicine. 2015;133:216–222. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeVerteuil G, Marr M, Snow D. Any space left? Homeless resistance by place-type in Los Angeles County. Urban Geography. 2009;30(6):633–651. [Google Scholar]

- England M. Stay out of drug areas: Drugs, othering and regulation of public space in Seattle, Washington. Space and Polity. 2008;12(2):197–213. [Google Scholar]

- Herbert S, Beckett K. ‘This is home for us’: questioning banishment from the ground up. Social & Cultural Geography. 2010;11(3):231–245. [Google Scholar]

- Hill G. Use of Pre-Existing Exclusionary Zones as Probationary Conditions for Prostitution Offenses: A Call for the Sincere Application of Heightened Scrutiny. The Seatle UL Rev. 2004;28(4/5):173–209. [Google Scholar]

- Jung JK. Computer-aided qualitative GIS: A software-level integration of qualitative research and GIS. Qualitative GIS: A mixed methods approach. 2009:115–136. [Google Scholar]

- Jung JK, Elwood S. Extending the Qualitative Capabilities of GIS: Computer-Aided Qualitative GIS. Transactions in GIS. 2010;14(1):63–87. [Google Scholar]

- Kallin H, Slater T. Activating territorial stigma: gentrifying marginality on Edinburgh’s periphery. Environment and Planning A. 2014;46(6):1351–1368. [Google Scholar]

- Keene DE, Padilla MB. Race, class and the stigma of place: Moving to “opportunity” in Eastern Iowa. Health & Place. 2010;16(6):1216–1223. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2010.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keene DE, Padilla MB. Spatial stigma and health inequality. Critical Public Health. 2014;24(4):392–404. [Google Scholar]

- Kerr T, Small W, Wood E. The public health and social impacts of drug market enforcement: A review of the evidence. International Journal of Drug Policy. 2005;16(4):210–220. [Google Scholar]

- Liu S, Blomley N. Making news and making space: Framing Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside. The Canadian Geographer. 2013;57(2):119–132. [Google Scholar]

- Maher L, Dixon D. Policing and public health: Law enforcement and harm minimization in a street-level drug market. British Journal of Criminology. 1999;39(4):488–512. [Google Scholar]

- Marshall BDL, Wood E, Shoveller JA, Patterson TL, Montaner JSG, Kerr T. Pathways to HIV risk and vulnerability among lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgendered methamphetamine users: a multi-cohort gender-based analysis. BMC Public Health. 2011;11(1):20. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCann K, Akin R, Airth C. Sex Work Enforcement Guidelines. Vancouver, BC: Vancouver Police Department; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- McCormick NJ, Joseph ML, Chaskin RJ. The New Stigma of Relocated Public Housing Residents: Challenges to Social Identity in Mixed-Income Developments. City & community. 2012;11(3):285–308. [Google Scholar]

- McNeil R, Kerr T, Lampkin H, Small W. “We need somewhere to smoke crack”: An ethnographic study of an unsanctioned safer smoking room in Vancouver, Canada. International Journal of Drug Policy. 2015;26(1):645–652. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2015.01.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNeil R, Shannon K, Shaver L, Kerr T, Small W. Negotiating place and gendered violence in Canada’s largest open drug scene. International Journal of Drug Policy. 2014;25(3):608–615. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2013.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNeil R, Small W. ‘Safer environment interventions’: A qualitative synthesis of the experiences and perceptions of people who inject drugs. Social Science & Medicine. 2014;106(0):151–158. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.01.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNeil R, Small W, Lampkin H, Shannon K, Kerr T. “People Knew They Could Come Here to Get Help”: An Ethnographic Study of Assisted Injection Practices at a Peer-Run ‘Unsanctioned’Supervised Drug Consumption Room in a Canadian Setting. AIDS and Behavior. 2014;18(3):473–485. doi: 10.1007/s10461-013-0540-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell D. The right to the city: Social justice and the fight for public space. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell D, Heynen N. The geography of survival and the right to the city: Speculations on surveillance, legal innovation, and the criminalization of intervention. Urban Geography. 2009;30(6):611–632. [Google Scholar]

- Moser SL. Anti-Prostitution Zones: Justifications for Abolition. Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology. 2001:1101–1126. [Google Scholar]

- Quesada J, Hart LK, Bourgois P. Structural Vulnerability and Health: Latino Migrant Laborers in the United States. Medical Anthropology. 2011;30(4):339–362. doi: 10.1080/01459740.2011.576725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarang A, Rhodes T, Sheon N, Page K. Policing drug users in Russia: risk, fear, and structural violence. Substance use & Misuse. 2010;45(6):813–864. doi: 10.3109/10826081003590938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shannon K, Rusch M, Shoveller J, Alexson D, Gibson K, Tyndall MW. Mapping violence and policing as an environmental–structural barrier to health service and syringe availability among substance-using women in street-level sex work. International Journal of Drug Policy. 2008;19(2):140–147. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2007.11.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shannon K, Strathdee SA, Shoveller J, Rusch M, Kerr T, Tyndall MW. Structural and environmental barriers to condom use negotiation with clients among female sex workers: implications for HIV-prevention strategies and policy. American Journal of Public Health. 2009;99(4):659–665. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.129858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Small W, Kerr T, Charette J, Schechter MT, Spittal PM. Impacts of intensified police activity on injection drug users: Evidence from an ethnographic investigation. International Journal of Drug Policy. 2006;17(2):85–95. [Google Scholar]

- Small W, Krusi A, Wood E, Montaner J, Kerr T. Street-level policing in the Downtown Eastside of Vancouver, Canada, during the 2010 winter Olympics. International Journal of Drug Policy. 2012;23(2):128–133. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2011.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Small W, Maher L, Lawlor J, Wood E, Shannon K, Kerr T. Injection drug users’ involvement in drug dealing in the downtown eastside of Vancouver: Social organization and systemic violence. International Journal of Drug Policy. 2013;24(5):479–487. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2013.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith N. The new urban frontier: gentrification and the revanchist city. New York, NY: Routledge; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Strathdee SA, Patrick DM, Currie SL, et al. Needle exchange is not enough: lessons from the Vancouver injecting drug use study. AIDS. 1997;11:59–65. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199708000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sylvestre M-E, Bernier D, Bellot C. Zone Restriction Orders in Canadian Courts and the Reproduction of Socio-Economic Inequality. Onati Socio-legal Series In press. [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi LM. The socio-spatial stigmatization of homelessness and HIV/AIDS: toward an explanation of the NIMBY syndrome. Social Science & Medicine. 1997;45(6):903–914. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(96)00432-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor B, Brownstein HH. Toward the operationalization of drug markets stability: An illustration using arrestee data from crack cocaine markets in four urban communities. Journal of Drug Issues. 2003;33(1):173–198. [Google Scholar]

- Tempalski B, McQuie H. Drugscapes and the role of place and space in injection drug use-related HIV risk environments. International Journal of Drug Policy. 2009;20(1):4–13. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2008.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wacquant L. Territorial stigmatization in the age of advanced marginality. Thesis Eleven. 2007;91(1):66–77. [Google Scholar]

- Wacquant L. Urban outcasts: A comparative sociology of advanced marginality. Cambridge, UK: Polity Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Wacquant L. Punishing the poor: The neoliberal government of social insecurity. Durham, NC: Duke University Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Wacquant L, Slater T, Pereira VB. Territorial stigmatization in action. Environment and Planning A. 2014;46(6):1270–1280. [Google Scholar]

- Werb D, Wood E, Small W, Strathdee S, Li K, Montaner J, Kerr T. Effects of police confiscation of illicit drugs and syringes among injection drug users in Vancouver. International Journal of Drug Policy. 2008;19(4):332–338. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2007.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood E, Kerr T, Small W, Jones J, Schechter MT, Tyndall MW. The impact of a police presence on access to needle exchange programs. JAIDS Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2003;34(1):116–117. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200309010-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood E, Montaner JSG, Yip B, Tyndall MW, Schechter MT, O’Shaughnessy MV, Hogg RS. Adherence and plasma HIV RNA responses to highly active antiretroviral therapy among HIV-1 infected injection drug users. Canadian Medical Association Journal. 2003;169(7):656–661. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood E, Stoltz JA, Montaner JSG, Kerr T. Evaluating methamphetamine use and risks of injection initiation among street youth: the ARYS study. Harm Reduction Journal. 2006;3(1):18. doi: 10.1186/1477-7517-3-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]