Abstract

Apolipoprotein A-I (ApoA-I), the major lipid-binding protein of high-density lipoprotein (HDL), can prevent autoimmunity and suppress inflammation in hypercholesterolemic mice by attenuating lymphocyte cholesterol accumulation and removing tissue oxidized lipids. However, whether ApoA-I mediates immune suppressive or anti-inflammatory effects in normocholesterolemic conditions and the mechanisms involved remain unresolved. We transferred bone marrow from SLE-prone Sle123 mice into normal, ApoA-I knockout (ApoA-I−/−) and ApoA-I transgenic (ApoA-Itg) mice. Increased ApoA-I in ApoA-Itg mice suppressed CD4+ T and B cell activation without changing lymphocyte cholesterol levels or reducing major ApoA-I-binding oxidized fatty acids. Unexpectedly, oxidized fatty acid peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARγ) ligands 13-hydroxyoctadecadienoic acid (HODE) and 9-HODE were increased in lymphocytes of autoimmune ApoA-Itg mice. ApoA-I reduced Th1 cells independently of changes in CD4+FoxP3+ regulatory T cells or CD11c+ dendritic cell activation and migration. Follicular helper T cells, germinal center B cells and autoantibodies were also lower in ApoA-Itg mice. Transgenic ApoA-I also improved SLE-mediated glomerulonephritis. However, ApoA-I deficiency did not have opposite effects on autoimmunity or glomerulonephritis, possibly due to compensatory increases of ApoE on HDL. We conclude that although compensatory mechanisms prevent pro-inflammatory effects of ApoA-I deficiency in normocholesterolemic mice, increasing ApoA-I can attenuate lymphocyte activation and autoimmunity in SLE independently of cholesterol transport, possibly through oxidized fatty acid PPARγ ligands, and can reduce renal inflammation in glomerulonephritis.

INTRODUCTION

Apolipoprotein A-I (ApoA-I) is the major cholesterol and lipid binding protein component of high-density lipoprotein (HDL) and as such confers many of its protective properties in atherosclerosis (1). Although the ability of ApoA-I to counteract excessive cellular cholesterol accumulation and promote reverse cholesterol transport (RCT) have been linked to anti-inflammatory action of HDL in rodent atherosclerosis models (2, 3), other mechanisms are thought to be additionally involved (4). These include the binding and hydrolysis of oxidized lipids by HDL-associated ApoA-I and paraoxonase-1 (PON-1) enzymatic activity respectively, which contribute to anti-inflammatory effects of HDL in hypercholesterolemic mice (5). For example, oxidized metabolites of linoleic and arachidonic acids (hydroxyoctadecadienoic [HODE] and hydroxyeicosatetraenoic [HETE] acids respectively) that have pro-inflammatory effects on vascular cells are abundantly produced in atherosclerosis by the action of lipoxygenase (LO) enzymes and reactive oxygen species (ROS) (6) and are reduced by ApoA-I in concert with its vaso-protective and anti-atherogenic action in hypercholesterolemic atherosclerosis models (5, 7).

There is considerable evidence from studies in hypercholesterolemic animal models to support the notion that modulating ApoA-I could alter the levels of cholesterol in lymphoid tissue and other organs to affect immune activation and inflammation in autoimmune settings. For example, ApoA-I deficiency in hypercholesterolemic low-density lipoprotein receptor knockout mice causes excessive lymphocyte cholesterol accumulation in lymph nodes, resulting in hyperproliferation of T lymphocytes and the development of systemic autoimmunity resembling systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) (8). Impaired immune cell cholesterol homeostasis caused by deficiency of the liver X receptor (LXR) pathway or scavenger receptor BI (a receptor involved in hepatic cholesterol ester uptake from HDL) similarly caused lymphocyte hyperproliferation and the development of SLE-like disease (9–11). The common mechanism mediating the autoimmune phenotypes in these hypercholesterolemic settings is the abnormally high immune cell cholesterol accumulation which causes immune hyperactivation at least in part through modulation of membrane raft-dependent receptor signaling (2). It has therefore been suggested that ApoA-I is essential to prevent systemic autoimmunity resulting from excessive immune cell cholesterol accumulation under conditions of hypercholesterolemia or interrupted cholesterol transport in mice. Indeed, the notion that ApoA-I suppresses autoimmunity in hypercholesterolemia by counterbalancing excessive cellular cholesterol accumulation to dampen lymphocyte activation and proliferation is also supported by data in mice showing suppressive effects of genetic disruptions in cholesterol transport pathways on cellular activation and proliferation in other systems, including the hematopoietic stem cell compartment (12).

While data in hypercholesterolemic models have provided important insights into the interactions between HDL cholesterol metabolism and autoimmunity (2), their interpretation with respect to immunomodulatory properties of ApoA-I and HDL in SLE is confounded by the extremely high levels of hypercholesterolemia and disruption of homeostatic mechanisms controlling cellular cholesterol levels in the animal models employed. As a result, questions exist over their physiological relevance, particularly considering the disappointing outcome of clinical trials in coronary heart disease patients of an ApoA-I mimetic peptide, 4F, which can provide robust anti-inflammatory and anti-atherogenic effects in hypercholesterolemic rodent models by recapitulating cholesterol and oxidized lipid binding properties of ApoA-I (13, 14). Indeed, the high expectations for 4F as a therapeutic were based largely on its effects in hypercholesterolemic animal models, with comparatively little data from normocholesterolemic animal models that are not compromised by confounding effects of hypercholesterolemia on inflammation and the immune system. Furthermore, the role of oxylipids like HODEs and HETEs that are typically involved in atherosclerosis and bound by ApoA-I in concert with its anti-inflammatory action in hypercholesterolemic mouse models have not been investigated in autoimmune settings like SLE. There is therefore no direct evidence that modulating ApoA-I can provide immune suppression in autoimmune settings without hypercholesterolemia and it is not known whether ApoA-I can modify cellular and molecular pathways to suppress relevant immune processes such as lymphocyte activation unless they are first pushed in the opposite direction (hyperactivated) by hypercholesterolemia (15).

Further underscoring the need for studies in normocholesterolemic models to test immune suppressive and anti-inflammatory properties of ApoA-I, SLE is associated with lower ApoA-I (HDL) levels and the development of dysfunctional pro-inflammatory HDL which may contribute to premature atherosclerosis in SLE patients (16–18). It has also been suggested that these reductions in ApoA-I (HDL) levels and function in SLE might feedback onto autoimmunity itself, amplifying immune activation, autoantibody production and organ inflammation. However, this has not been addressed in the context of normocholesterolemic SLE models with modified ApoA-I (HDL) levels. We therefore employed a normocholesterolemic bone marrow transfer model of SLE to test whether modulating ApoA-I levels can provide immune suppression in SLE despite an underlying predisposition for HDL to become reduced or dysfunctional, to characterize the cellular and molecular mechanisms involved, and identify lipid based immune suppressive pathways mediated by ApoA-I that could be exploited therapeutically in SLE.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice

C57BL/6J (WT), C57BL/6J ApoA-I−/−, C57BL/6J ApoA-Itg (containing approximately twice the normal levels of plasma ApoA-I (19)) and Sle123 mice were obtained from Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME) and colonies were maintained at the University of Alabama at Birmingham. Female mice were weaned at four weeks of age and maintained on a standard rodent chow diet for the duration of the study. All studies were conducted in conformity with Public Health Service (PHS) Policy on Humane Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and with approval from the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Alabama at Birmingham.

Bone marrow transplantation (BMT)

Bone marrow (BM) transplantations were conducted as previously described (20). To distinguish donor from recipient BM-derived cells colonies of WT, ApoA-I−/− and ApoA-Itg mice expressing the differential Ly5.1 (CD45.1) alloantigen were derived by crossing with the B6.SJL-Ptprca Pep3b/BoyJ strain of C57BL/6J mice (Jackson Laboratories). Ly5.1 C57BL/6J, Ly5.1 ApoA-I−/− and Ly5.1 ApoA-Itg recipients were lethally irradiated (two doses of 450 RADS ionizing radiation spaced by three hours) and transplanted at six weeks of age with 5×106 BM mononuclear cells from Ly5.2 WT or Ly5.2 Sle123 donor mice. Peripheral blood samples were collected by retro-orbital puncture and processed for flow cytometric analysis of reconstitution of major hematopoietic lineages using the following conjugated antibodies: anti-CD4 [RM4–5] PerCP, anti-CD8 [53–6.7] FITC, anti-CD11b [M1/70] PE, anti-CD19 PerCP [1D3] (BD Pharmingen, San Jose, CA), anti-Ly5.1 [A20] FITC or PE, anti-Ly5.2 [104] APC (Southern Biotech, Birmingham, AL). No aberrant ApoA-I specific antibody responses were generated as a result of BM transfer into WT or ApoA-I gene targeted mice (by anti-human ApoA-I and anti-mouse ApoA-I ELISA; as in (18); data not shown).

Measurement of plasma autoantibodies

Anti-dsDNA autoantibody levels were measured by ELISA as previously described (18). Ninety-six well MaxiSorp plates (Thermoscientific, Waltham, MA) were coated with dsDNA (0.24 µg/well; Sigma, St. Louis, MO) in bicarbonate buffer (150mM Na2CO3, 350mM NaHCO3 [pH 9.7]) overnight at 4°C. Plates were washed with PBS containing 0.5% Tween 20 (PBST) using an automated plate washer (BioTek, Winooski, VT) and blocked with 3% nonfat milk/PBS. Plates were subsequently incubated with diluted plasma (1:100 in PBS) for 2 hours, washed, and incubated with horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG at 1:5,000 (Southern Biotech, Birmingham, AL) in blocking buffer. Plates were washed, developed with tetramethylbenzidine substrate (Pierce, Rockford, IL), and measured on a Bio-Rad Model 680 microplate reader (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) at 450 nm.

Flow cytometry

Single cell suspensions were prepared from collagenase D (Roche, Indianapolis, IN) digested lymph nodes (axillary, superficial cervical, brachial, inguinal, and iliac) as described previously (18). Cells were washed with 10mM EDTA/PBS, resuspended in 5% FBS/PBS, counted and stained for flow cytometric analysis in the presence of anti CD16/32 (Fc Block) (UAB Epitope Recognition and Immunoreagent Core Facility). Data were acquired using a BD FACSCalibur flow cytometer and analyzed using FlowJo software (TreeStar, Ashland, OR). The following conjugated antibodies were used: anti-CD4 [RM4–5] PerCP, anti-CD8 [53–6.7] APC, anti-B220 [RA3–6B2] PE, anti-CD11c [HL3] PE, anti-CD69 [H1.2F3] FITC, anti-CD44 [IM7] FITC, anti-CD62L [MEL-14] PE, anti-CD86 [GL1] FITC (BD Pharmingen, San Jose, CA), F4/80 [MF48024] PE (Life technologies, Grand Island, NY), and anti-MHCII [M5/114.15.2] PerCP (BioLegend, San Diego, CA). Intracellular FoxP3 staining was performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions using a Mouse Regulatory T Cell Staining Kit (eBioscience, San Diego, CA). Intracellular BrdU staining was performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions using an APC BrdU Flow Kit (BD Pharmingen, San Jose, CA); mice were given an i.p. injection of 1 mg BrdU five hours prior to analysis. Intracellular staining for interferon-γ (IFNγ) secreting CD4+ Th1 and IL-17 secreting CD4+ Th17 cells was performed following a four hour stimulation at 37°C with 1× Cell Stimulation Cocktail in the presence of 1× brefeldin A (eBioscience, San Diego, CA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions and subsequent cell surface staining for CD4. The following antibodies were used: anti-CD4 [RM4–5] PE or FITC (BD Pharmingen, San Jose, CA), anti-IFNγ [XMG1.2] PerCP, anti-IL17 [TC11–18H10.1] FITC (BioLegend, San Diego, CA). Prior to intracellular staining, cells were fixed and permeabilized using eBioscience’s FoxP3/Transcription Factor Staining Buffer Set according to the manufacturer’s instructions (eBioscience, San Diego, CA). Cell surface staining for T follicular helper cells was performed using the following conjugated antibodies: anti-CXCR5 [2G-8] biotin followed by anti-CD4 [RM4–5] PerCP (BD Pharmingen, San Jose, CA), anti-PD1 [J43] FITC (eBioscience, San Diego, CA), and Streptavidin APC (BD Pharmingen, San Jose, CA). Intracellular staining for BCL6 was performed using anti-BCL6 [K112–91] PE (BD Pharmingen, San Jose, CA) following cell fixation and permeabilization using eBioscience’s FoxP3/Transcription Factor Staining Buffer Set according to the manufacturer’s instructions (eBioscience, San Diego, CA). Staining for germinal center B cells was performed using the following conjugated antibodies: anti-CD19 [ID3] APC, anti-CD95 [Jo2] PE (BD Pharmingen, San Jose, CA) and PNA FITC (Sigma, St. Louis, MO).

FITC skin painting assay

Dendritic cell migration assays were conducted as described in Robbiani et al (21). WT, ApoA-I−/− and ApoA-Itg mice were anesthetized and their sides were shaved. FITC (8 mg/ml) was dissolved in sensitizer consisting of equal volumes of acetone and dibutyl phthalate (Sigma, St. Louis, MO). Twenty-five µl FITC containing sensitizer was applied to the right dorsal side of the mouse, while 25µl sensitizer alone was applied to the left dorsal side. Eighteen hours later, draining lymph nodes (axillary, brachial, inguinal) from each side (“control LNs” from left and “FITC LNs” from right) were removed and single cell suspensions were prepared by collagenase D digestion as described above for counting and flow cytometric analysis with anti-CD11c [HL3] PE antibody (BD Pharmingen, San Jose, CA).

Kidney morphometric analysis and histopathology

Kidneys were fixed in neutral buffered 10% formalin and processed routinely for paraffin sectioning. Five µm thick sections were stained with periodic acid-Schiff stain (PAS) and hematoxylin. Slides were examined with experimental classifications concealed from the observer. For morphometric analysis, nine glomeruli were evaluated per section as previously described (22). To minimize selection bias, glomeruli were selected beginning at the capsule at the 12 o’clock position of the section and proceeding clockwise, selecting only centrally sectioned glomeruli having open capillary lumina and avoiding collapsed or tangentially sectioned glomeruli. Images of selected glomeruli were made with a SPOT Insight 4 megapixel digital camera (Diagnostic Instruments, Sterling Heights, Michigan) at an objective magnification of 40×. After adjustment for sharpness, contrast, and brightness to maximize visibility of PAS staining, images were analyzed by histomorphometry for total glomerular area, PAS stained area, and nuclear area with Image Pro Plus v6.2 image analysis software (Media Cybernetics, Silver Spring, Maryland) by thresholding grayscaled images, color segmentation of color images, or both. Glomeruli were also evaluated by subjective scoring, without the pathologist’s knowledge of the genotype of the mice, as previously described (22, 23). Glomerular cellularity, neutrophil infiltration, necrosis, hyaline deposits, mesangial expansion, cellular crescent formation, and interstitial inflammatory cell accumulation were evaluated. Each was scored 0, 1, 2, or 3 for normal, mild, or severe, respectively. Equal numbers of glomeruli from superficial, middle, and deep cortex were examined. Only glomeruli sectioned through the approximate center of the tuft and including the base of the tuft were included. Overall glomerular activity scores for each mouse were calculated as the mean of summed individual scores for each glomerulus, with scores for necrosis and crescent formation each weighted by a factor of 2 as follows (proliferation [cellularity] + neutrophil infiltration + necrosis2 + hyaline deposits + mesangial expansion + cellular crescent formation2 + interstitial inflammatory cell infiltration).

Kidney immunofluorescence analysis

Eight µm cryosections prepared from kidneys in optimum cutting temperature compound (Tissue-Tek) were fixed in acetone and stained with goat anti-mouse IgG-Alexa594 (Life technologies, Grand Island, NY), rat anti-mouse CD4 [GK1.5], rat anti-mouse CD11b [M1/70] (BD Pharmingen, San Jose, CA), or rat anti-murine neutrophil [NIMP-R14] (Thermo Fisher) (24) antibodies. Goat anti-rat IgG-Alexa555 conjugated secondary antibody (Life technologies, Grand Island, NY) was used for sections stained with anti-CD4, anti-CD11b and anti-murine neutrophil primary antibodies. Color images were captured on an Olympus BX60 microscope using a 40× objective. For quantification of IgG and CD11b, average fluorescence intensity was quantified from six representative 400× microscopic fields per kidney cryosection using the histogram function of Adobe Photoshop CS5.1 (Adobe Systems, San Jose, CA) as previously described (25). For CD4 and neutrophil quantification, the numbers of CD4+ T cells and neutrophils were enumerated from six representative 400× microscopic fields per kidney cryosection by counting Hoechst stained nuclei that were positive for cytoplasmic CD4 or NIMPR14 staining.

Urine albumin and creatinine measurement

Urine albumin was quantified using a Mouse Albumin ELISA Quantitation Set (Bethyl Laboratories, Inc.) according to the manufacturer’s instructions at a sample dilution of 1:1000. Urine albumin and creatinine was measured in spot urine samples taken at euthanization for the control and Sle123 BMT animal groups. Urine creatinine was determined by underivatized, stable isotope dilution LC-MS/MS as described in Young et al (26). Briefly, samples were separated using a Waters 2795 separations module (LC) (Waters, Milford, MA) with a TSK-Gel Amide 80 column (Tosoh Bioscience, Tokyo, Japan) with an isocratic flow of 10mM ammonium acetate in 65% acetonitrile, and creatinine was subsequently detected by Waters Quattro micro API (MS/MS) in the positive ion mode.

Lipoprotein and lipid analyses

Plasma lipids were processed for measurement of total cholesterol, esterified cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, LDL-cholesterol, triglycerides and free fatty acids by enzymatic procedures as previously described (27). To obtain FPLC plasma cholesterol profiles, plasma (200 µl pooled from 2 mice) was fractionated using a Superose 6 column (Amersham Biosciences, GE Life Sciences, Pittsburgh, PA) on a Biologic DuoFlow FPLC system (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) as previously described (20). One-half ml fractions were collected and analyzed for total cholesterol content using enzymatic cholesterol reagents (Infinity Cholesterol Reagent TR13421, Thermo Scientific). Total plasma and fractionated plasma PON1 paraoxonase activity were measured using 1 mM Paraoxon (Supelco Analytical, Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) in 50 mM Tris/HCl pH 8.0, 1mM CaCl2 as previously described (18).

Cholesterol Analysis by Gas Chromatography Mass Spectrometry (GC/MS)

GC-MS cholesterol analyses were performed in the Mass Spectrometer Facility (MJT) of the Comprehensive Cancer Center of Wake Forest School of Medicine. Lipids were extracted from ten million lymph node lymphocyte cells prepared by forcing lymph nodes through 100µm strainers as described by Wilhelm et al (8). Lipids were resuspended in 200µl hexane and 100µl analyzed on a Finnigan TSG Quantum XLS mass spectrometer interfaced to a trace gas chromatograph as described by Wilhelm et al (8). To quantify esterified cholesterol levels, a 50µl hexane lipid aliquot was also saponified at room temperature for 2 hours with methanolic KOH as described by Nordskog et al (28) and then extracted with hexane as described by Wilhelm et al (8) prior to GC-MS.

SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting

Plasma FPLC fractions (5µl) were separated on 4–15% mini-Protean TGX gels (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) and transferred to Immobilon P membranes (Millipore, Billerica, MA) as previously described (20). Membranes were blocked with PBST containing 5% nonfat milk by weight, incubated with primary antibodies diluted 1:2,000 in blocking buffer [Rabbit anti-mouse ApoA-I, rabbit anti-mouse ApoE, and/or goat anti-human ApoA-I (Meridian Life Sciences, Inc., Memphis, TN)] followed by HRP-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) or donkey anti-goat IgG (Southern Biotech, Birmingham, AL) secondary antibodies diluted 1:4,000 in blocking buffer. Immunoreactive proteins were visualized using enhanced chemiluminescence (ImmunStar, Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). Neat plasma (1µl) samples were separated on 4–15% mini-Protean TGX gels (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) and transferred to Immobilon FL membranes (Millipore, Billerica, MA). Membranes were blocked with PBST containing 5% nonfat milk by weight, incubated with primary antibodies diluted 1:2,000 in blocking buffer [Rabbit anti-mouse ApoA-I, rabbit anti-mouse ApoE, goat anti-human ApoA-I (Meridian Life Sciences, Inc., Memphis, TN) or rabbit anti-mouse ApoA-II (29)] followed by IRDye 800CW-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit IgG or IRDye 680RD-conjugated donkey anti-goat IgG secondary antibodies (Li-Cor, Lincoln, NE) diluted 1:40,000 in blocking buffer. Immunoreactive proteins were visualized using Li-Cor’s Odyssey CLx Infrared Imaging System (Li-Cor, Lincoln, NE). Acquired images were adjusted for optimal brightness and contrast, and band intensities were quantified using Image Studio Analysis Software v3.1 (Li-Cor, Lincoln, NE).

HODE/HETE measurement

For plasma HODE/HETE measurement, butylated hydroxytolune (BHT) was added to freshly isolated 100µl plasma aliquots to a final BHT concentration of 100µM and overlayed with argon gas prior to storage at −80°C. Lipids were extracted from 100µl plasma aliquots and analyzed by LC-MS/MS as described in Imaizumi et al (7) using a Shimadzu prominence HPLC system and an AB/Sciex API-4000 Q TRAP mass spectrometer. Aliquots (100µl) of plasma were acidified by addition of 1.7ml of pH2.3 H2O, vortexed briefly and incubated on ice for 15 minutes. Deuterated standards for each measured HODE and HETE (20ng of each) (Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbor, MI) were spiked into samples prior to extraction. Samples were subsequently added to solid phase extraction (SPE) columns (Oasis® HLB 30mg 1cc; Waters, Milford, MA #WAT094225) while pulling a slow vacuum so that each sample took approximately 2 minutes to pass through. After washing SPE columns with 1ml 5% methanol, lipids were eluted with 1ml 100% methanol, dried under argon and resuspended in 100µl 80% methanol. For HODEs and HETEs, lipids (50µl) were injected onto a Luna C18(2)-HST reverse-phase LC column (2×100mm, 2.5µ; Phenomenex, Torrance, CA) using a Shimadzu auto-sampler with gradient elution at 0.3 ml/minute (mobile phase A: 0.1% formic acid in H2O, mobile phase B: 0.1% formic acid in acetonitrile). Gradient elution was as follows: from 0 min to 2 min hold at 50% B, from 2–3 min increase to 60% B, from 3–15 min an increase to 65% B, from 15–17 min hold at 65% B, from 17–19 min an increase to 100% B, from 19–21 min hold at 100% B, from 21–23 min decrease back to 50% B and a hold for the system to equilibrate to initial conditions until 27 min. For Linoleic acid and arachidonic acid, lipids (50µl) were injected onto a Luna C12 Proteo reverse-phase LC column (2×50mm, 4µ; Phenomenex, Torrance, CA) using a Shimadzu auto-sampler with gradient elution at 0.25 ml/minute (mobile phase A: 10mM ammonium acetate in H2O, mobile phase B: 10mM ammonium acetate in isopropyl alcohol). Gradient elution was as follows: from 0 min to 10 min increase from 35% B to 100% B, from 10–11 min decrease from 100% B to 35% B, from 11–17 min hold at 35% B for the system to equilibrate to initial conditions. A standard curve (0.1, 1, 2.5, 5, 7.5, 10, 25, 50, 75, 100, 250, 500, 750, 1000ng/ml) of a mixture of unlabeled linoleic acid, arachidonic acid, HODEs and HETEs (13-HODE, 9-HODE, 15-HETE, 5-HETE, 12-HETE) were also run for quantification of individual fatty acid and HODE/HETE species. Each point of this standard curved was spiked with deuterated linoleic acid, arachidonic acid, HODEs/HETEs standards exactly as described above for samples (20ng of each deuterated fatty acid and HODE/HETE per standard curve point). The transitions monitored were the following mass-to-charge ratio (m/z): m/z 295.1→194.8 for 13-HODE; 295.0→171.0 for 9-HODE; 319.1→219.0 for 15-HETE; 319.1→115.0 for 5-HETE; 319.1→179.0 for 12-HETE; 299.0→197.9 for 13(S)-HODE-d4; 299.1→172.0 for 9(S)-HODE-d4; 327.1→226.1 for 15(S)-HETE-d8; 327.1→116.0 for 5(S)-HETE-d8; 327.1→184.0 for 12(S)-HETE-d8, 303.0→59.0 for arachidonic acid, 311.0→267.0 for arachidonic acid-d8, 279.0→261.0 for linoleic acid, 283.0→265.0 for linoleic acid-d4.

Statistics

Statistical analysis was performed using SigmaPlot 11 (Systat Software, Inc., San Jose, CA). One-way ANOVA was used for multiple comparisons and Student t-test was used for single comparisons. For all statistical analyses, p<0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

Transgenic expression of ApoA-I suppresses lymphocyte activation and autoimmunity

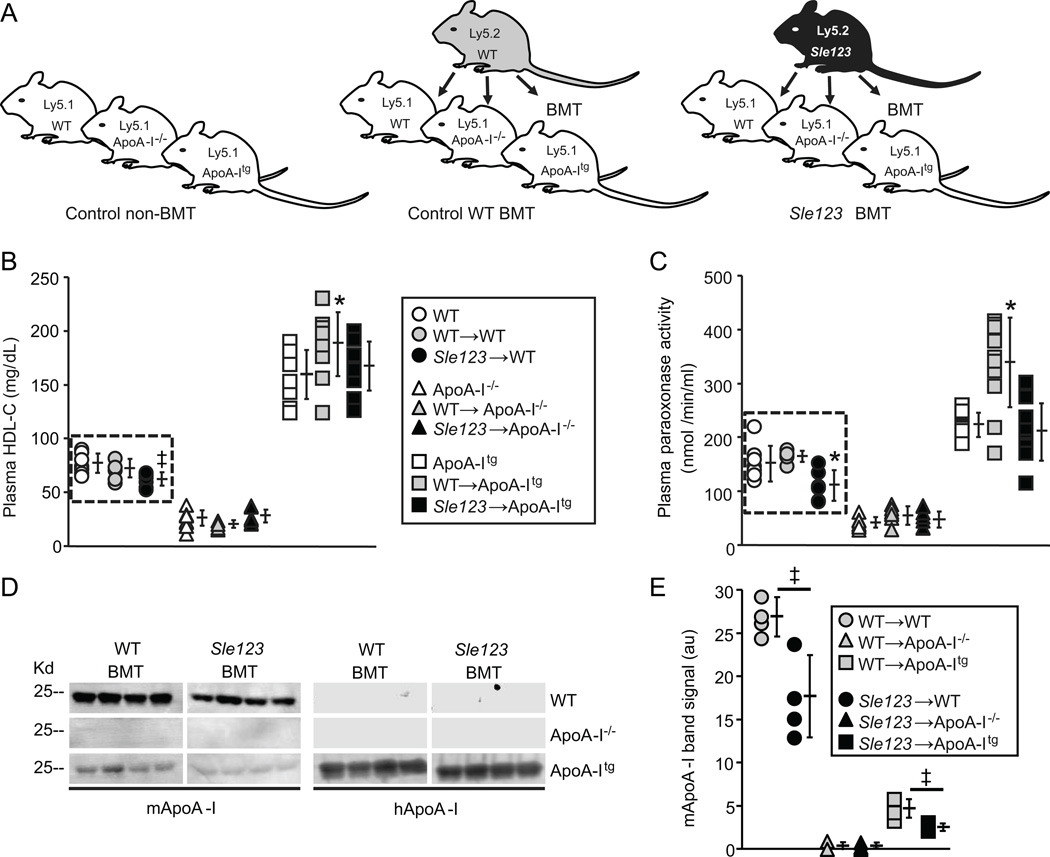

We transplanted bone marrow (BM) from Ly5.2 SLE-prone Sle123 mice into 6 week old Ly5.1 wild-type (WT), Ly5.1 ApoA-I knockout (ApoA-I−/−) or Ly5.1 human ApoA-I transgenic (ApoA-Itg) mice (Sle123→WT, Sle123→ApoA-I−/− and Sle123→ApoA-Itg). BM transplanted (BMT) animals were subsequently bled at intervals and analyzed at 38 weeks of age (32 weeks post-BMT) to measure autoimmune phenotypes and glomerulonephritis (GN). Groups of Ly5.1 WT, Ly5.1 ApoA-I−/− and Ly5.1 ApoA-Itg mice were also transplanted with Ly5.2 WT BM (WT→WT, WT→ApoA-I−/− and WT→ApoA-Itg control BMT groups) in order to control for effects of lethal irradiation and hematopoietic reconstitution. A schematic representation of this BM transplantation (BMT) scheme is shown in Figure 1A. Myeloid and lymphoid repopulation was equivalent between WT, ApoA-I−/− and ApoA-Itg mice transplanted with Sle123 BM (Table I) such that any differences in autoimmune phenotypes could not be ascribed to differences in hematolymphoid reconstitution with Sle123 cells.

Figure 1.

(A) Schematic of BMT scheme used to generate chimeric autoimmune mice (animals were transplanted with WT or Sle123 BM at 6 weeks of age). (B) Plasma HDL-C levels in the indicated control, control WT BMT and Sle123 BMT mice (38 weeks of age, 32 weeks post-BMT, n=8). (C) Plasma PON1 activity against paraoxon substrate in the indicated control, control WT BMT and Sle123 BMT mice (38 weeks of age, 32 weeks post-BMT, n=8). Note autoimmune-mediated reductions in HDL-cholesterol (HDL-C) and HDL-associated PON1 activity in Sle123→WT mice (in dashed box). (D) Plasma levels of mouse ApoA-I (mApoA-I) and human ApoA-I (hApoA-I) in 4 control and 4 Sle123 BMT mice (38 weeks of age, 32 weeks post-BMT). Graph showing band intensities for plasma mApoA-I is shown in (E). Note reduction in plasma mApoA-I in Sle123→WT mice compared to their control WT counterparts. ApoA-Itg animals have markedly lower endogenous mApoA-I levels as previously reported (19). (All data mean ± SD, *p<0.05 by one way ANOVA within WT, ApoA-I−/− or ApoA-Itg group, ‡p<0.05 by T test compared to control group).

Table I.

Hematopoietic reconstitution (%Ly5.2 in peripheral blood cells of the indicated lineages) in WT, ApoA-I−/− and ApoA-Itg BM transplanted mice (38 weeks of age).

| Recipient (Ly5.1) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WT | ApoA-I−/− | ApoA-Itg | ||||

|

Donor (Ly5.2) |

WT |

4 weeks post-BMT |

23.0 ±10.7 (n=6) | 31.9 ±15.6 (n=6) | 28.0 ±15.2 (n=6) | CD4+ |

| 29.2 ± 8.9 (n=6) | 30.8 ±13.5 (n=6) | 32.5 ±14.1 (n=6) | CD8+ | |||

| 93.7 ±3.1 (n=6) | 99.0 ±0.4 (n=6) | 96.8 ±0.4 (n=6) | CD19+ | |||

| 92.5 ±5.2 (n=6) | 97.3 ±1.7 (n=6) | 93.4 ±1.6 (n=6) | CD11b+ | |||

|

32 weeks post-BMT |

88.8 ±4.8 (n=10) | 92.0 ±1.9 (n=10) | 92.3 ±1.8 (n=10) | CD4+ | ||

| 83.8 ±6.5 (n=10) | 89.9 ±3.4 (n=10)§ | 82.6 ±5.5 (n=10) | CD8+ | |||

| 97.6 ±1.9 (n=10) | 99.0 ±0.4 (n=10) | 95.0 ±1.3 (n=10) | CD19+ | |||

| 93.1 ±5.1 (n=10) | 97.3 ±3.1 (n=10) | 95.0 ±1.3 (n=10) | CD11b+ | |||

| Sle123 |

4 weeks post-BMT |

46.6 ±7.3 (n=12)‡ | 51.1 ±7.1 (n=12) ‡ | 40.4 ±6.3 (n=12)* | CD4+ | |

| 45.7 ±9.6 (n=12)‡ | 52.3 ±8.7 (n=12)‡ | 39.5 ±8.5 (n=12)* | CD8+ | |||

| 96.7 ±1.3 (n=12) | 97.1 ±1.0 (n=12) | 97.0 ±0.6 (n=12) | CD19+ | |||

| 95.8 ±3.1 (n=12) | 96.3 ±1.5 (n=12) | 97.1 ±0.9 (n=12) | CD11b+ | |||

|

32 weeks post-BMT |

88.1 ±5.9 (n=12) | 88.3 ±4.1 (n=12)‡ | 89.5 ±4.6 (n=12) | CD4+ | ||

| 89.0 ±4.8 (n=12) | 89.3 ±3.3 (n=12) | 87.2 ±6.4 (n=12) | CD8+ | |||

| 94.5 ±2.8 (n=12)‡ | 97.8 ±0.9 (n=12) | 97.4 ±0.7 (n=12) | CD19+ | |||

| 97.5 ±1.2 (n=12)‡ | 96.0 ±2.6 (n=12) | 94.1 ±3.5 (n=12) | CD11b+ | |||

| %Ly5.2 | ||||||

p<0.05 compared to ApoA-I−/− mice (but not WT mice) of the same BMT donor group.

p<0.05 compared to the same host genotype transplanted with WT BM at the same time-point.

p<0.05 (One Way ANOVA) compared to WT and ApoA-I−/− mice of the same BMT donor group.

As expected, because BM-derived cells do not express ApoA-I (30) and ApoA-I is important for stabilizing PON-1 activity on HDL particles (31), plasma levels of HDL-cholesterol (HDL-C) and HDL-associated PON-1 activity were decreased in transplanted as well as control non-BMT ApoA-I−/− mice and increased in transplanted as well as control non-BMT ApoA-Itg animal groups (Figure 1B and C and Table II). As previously reported (32), plasma LDL-C and triglyceride levels were increased (Table II) and endogenous mouse ApoA-I (mApoA-I) levels were significantly reduced by post-transcriptional mechanisms in the ApoA-Itg animals (19) (Figure 1D–E). Despite these reductions in endogenous mApoA-I, total ApoA-I levels (mApoA-I plus human transgenic ApoA-I) are increased approximately 2-fold in ApoA-Itg mice (19).

Table II.

Lipid profiles in control, control WT BMT and Sle123 BMT WT, ApoA-I−/− and ApoA-Itg mice (38 weeks of age) (n=8).

| WT | ApoA-I−/− | ApoA-Itg | WT → WT |

WT → ApoA-I−/− |

WT → ApoA-Itg |

Sle123 → WT |

Sle123 → ApoA-I−/− |

Sle123 → ApoA-Itg |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

HDL-C (mg/dl) |

78.6 ±8.9 |

26.5 ±7.1‡ |

159.5 ±22.6‡ |

69.4 ±8.6 |

22.8 ±4.4‡ |

181.4 ±35.0‡ |

62.6 ±7.7* |

28.7 ±6.1‡ |

167.2 ±22.7‡ |

|

LDL-C (mg/dl) |

30.5 ±7.2 |

19.6 ±5.1 |

143.1 ±51.5‡* |

29.2 ±6.8 |

12.5 ±2.1 |

62.1 ±27.9‡ |

23.6 ±4.7 |

26.5 ±19.4 |

50.8 ±16.8‡ |

|

TG (mg/dl) |

24.7 ±11.1 |

27.9 ±15.3 |

72.5 ±24.0‡ |

36.4 ±10.6 |

26.8 ±5.9 |

46.7 ±30.0 |

38.8 ±50.4 |

25.0 ±13.3 |

62.5 ±20.8‡ |

|

FFA (mg/dl) |

24.2 ±6.2 |

19.6 ±2.6 |

33.0 ±8.6 |

28.0 ±6.2 |

15.5 ±6.4 |

20.3 ±6.0 |

27.5 ±10.2 |

20.8 ±4.7 |

22.2 ±6.3 |

|

PON-1 (nmol/min/ml) |

153.3 ±34.3 |

39.6 ±9.0‡ |

222.6 ±22.8‡ |

164.3 ±10.6 |

62.2 ±17.6‡ |

338.7 ±82.7‡* |

110.9 ±28.3* |

47.6 ±15.2‡ |

209.2 ±53.1‡ |

HDL-C = high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; LDL-C = low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; TG = triglycerides; FFA = free fatty acids; PON-1=paraoxonase-1. Values are the mean ± SD.

p<0.05 (One Way ANOVA) within the same host genotype group (WT, ApoA-I−/− or ApoA-Itg).

p<0.05 (One Way ANOVA) within the same control non-BMT, control WT BMT or Sle123 BMT group.

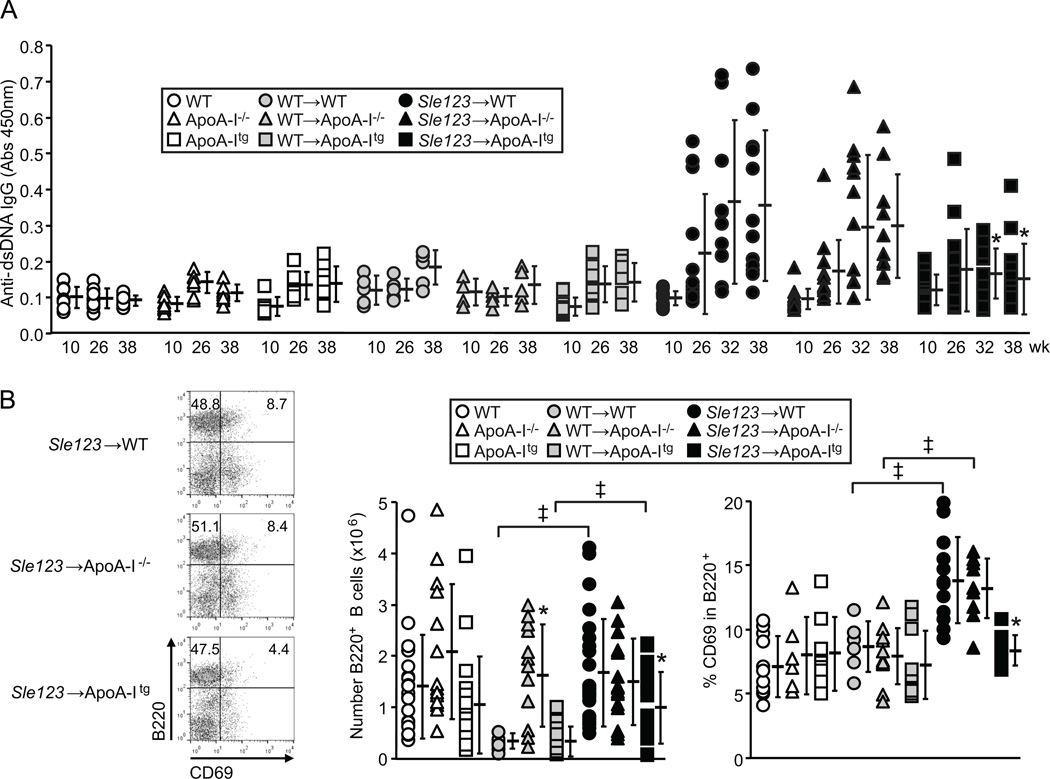

Plasma levels of anti-dsDNA IgG autoantibodies were significantly lower in Sle123→ApoA-Itg mice compared to their Sle123→WT and Sle123→ApoA-I−/− counterparts at 32 and 38 weeks of age (26 and 32 weeks post-BMT respectively) (Figure 2A). However, Sle123→ApoA-I−/− animals had comparable levels of autoantibodies to those in Sle123→WT animals at all time-points measured (Figure 2A). Although control WT BMT animals had reduced numbers of lymph node B cells and CD4+ T cells compared to their control non-BMT counterparts, presumably due to lethal irradiation and transplantation, autoimmune associated increases in lymphocytes were evident in the WT mice transplanted with Sle123 BM (Figures 2B and 3B). B cell numbers and activation were reduced in lymph nodes of Sle123→ApoA-Itg mice by 41% and 57% respectively (Figure 2B). Lymph node CD4+ (but not CD8+) T cell numbers and activation were reduced in Sle123→ApoA-Itg mice by 38% and 43% respectively (Figure 3). Similar suppressive effects of transgenic ApoA-I expression were observed in splenic B and CD4+ T cells from Sle123→ApoA-Itg mice (B cells reduced by 47%, CD4+ T cells reduced by 57%, CD8+ T cells not reduced). ApoA-I deficiency did not result in opposite effects, demonstrating that, unlike in hypercholesterolemic SLE models (8, 10, 11, 15), ApoA-I deficiency does not exacerbate autoimmunity under normal (normocholesterolemic) conditions in mice.

Figure 2.

Transgenic ApoA-I expression reduces B cell activation and anti-ds DNA IgG autoantibodies in Sle123→ApoA-Itg mice. (A) Anti-dsDNA autoantibody levels in control (n=7), WT BMT control (n=7) and Sle123 BMT (n=10) animal groups. Ages of animals in weeks on y-axis. (B) Flow cytometric analysis of lymph node B220+ B lymphocyte activation (measured by CD69 expression) in 38 week old control (n=12–15), control WT BMT (n=10–12) and Sle123 BMT (n=12–15) mice. Reduced numbers of B cells and lower B cell activation in Sle123→ApoA-Itg mice. (All data mean ± SD, *p<0.05 by one way ANOVA within control, control WT BMT or Sle123 BMT groups, ‡p<0.05 by T test compared to control).

Figure 3.

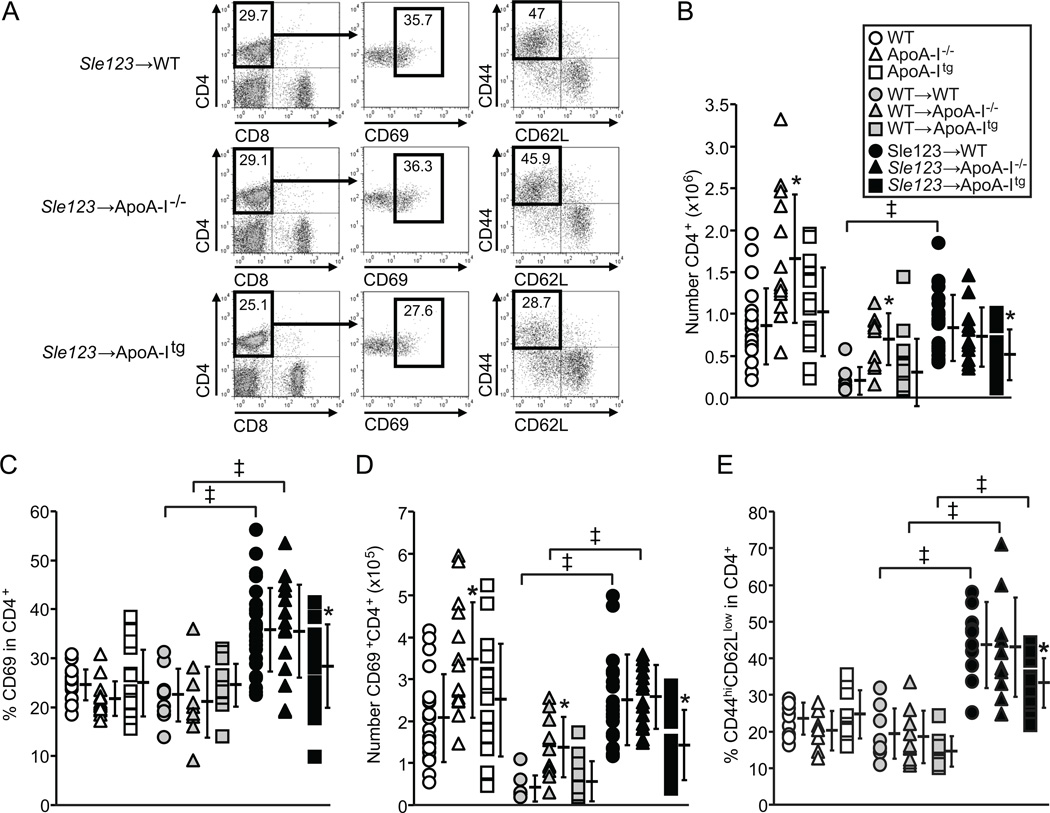

Reduced numbers and activation of CD4+ T lymphocytes in Sle123→ApoA-Itg mice. (A) Flow cytometric analysis (showing gates) of lymph node CD4+ T lymphocyte activation (measured by CD69 and CD44highCD62Llow expression) in 38 week old control, control WT BMT and Sle123 BMT mice. (B) Numbers of CD4+ T lymphocytes in lymph nodes of the indicated mice (n=12–15 control, n=10–12 control WT BMT, n=10–12 Sle123 BMT mice). (C–D) Percent and absolute numbers of CD69 expressing CD4+ T lymphocytes in lymph nodes of indicated mice. (E) CD44highCD62Llow CD4+ T lymphocytes in lymph nodes of indicated mice. Note that ApoA-I deficiency in this normocholesterolemic setting does not augment T cell activation. (All data mean ± SD, *p<0.05 by one way ANOVA within control, control WT BMT or Sle123 BMT groups, ‡p<0.05 by T test compared to control).

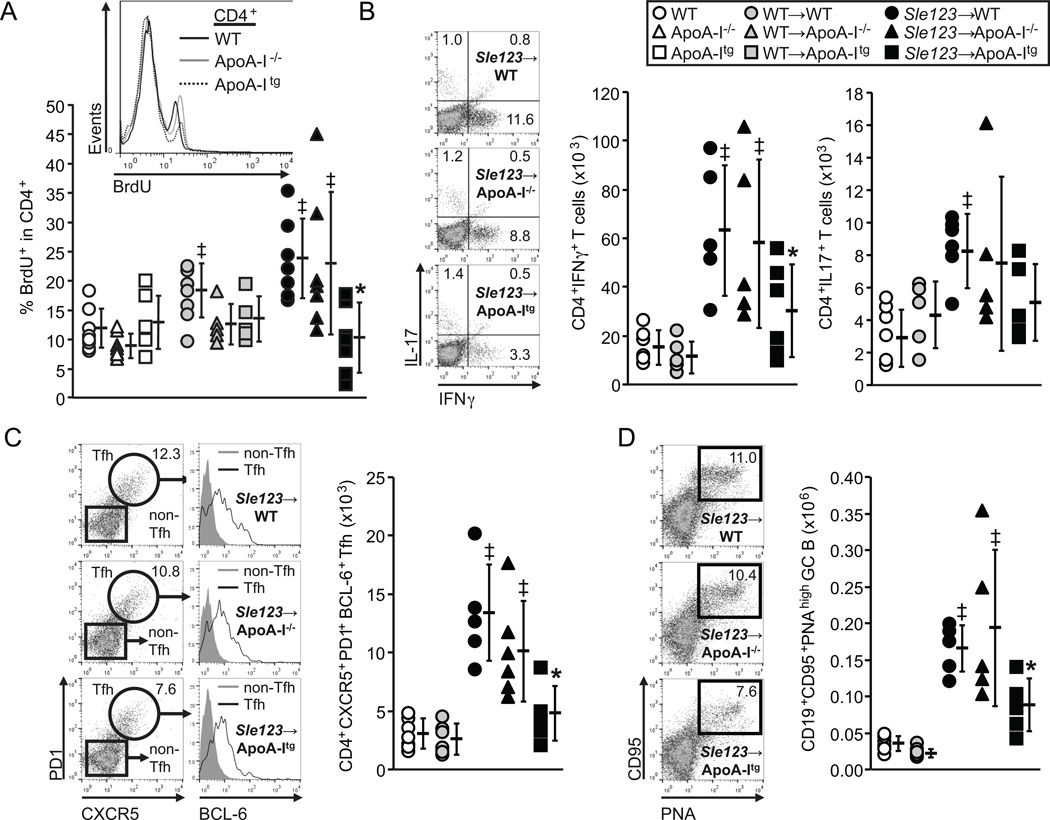

Consistent with fewer activated CD4+ T cells in Sle123→ApoA-Itg mice, numbers of proliferating CD4+ (but not CD8+) T cells were also reduced (by 58%) (Figure 4A). Importantly, this was not associated with a decreased rate of proliferation, as the level of BrdU incorporation into the CD4+ T cells as measured by BrdU mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) was equivalent between Sle123→WT, Sle123→ApoA-I−/− and Sle123→ApoA-Itg mice (59±9, 56±14 and 51±11 respectively). Thus, unlike in hypercholesterolemic mice in which the proliferative rate of T lymphocytes was increased by ApoA-I deficiency (8), loss or transgenic expression of ApoA-I in our normocholesterolemic Sle123 BMT model had no significant effect on the rate of T lymphocyte proliferation.

Figure 4.

Reduced frequency of proliferating CD4+ T cells, lower interferon-γ (IFNγ) secreting TH1 (but not IL-17 secreting TH17) and follicular T helper (Tfh) cells in Sle123→ApoA-Itg mice. (A) Flow cytometric analysis of in vivo BrdU incorporation into lymph node CD4+ T cells 6 hours following IP BrdU injection (n=8) (‡p<0.05 by T test compared to control non-BMT, *p<0.05 by one way ANOVA within control, control WT BMT or Sle123 BMT groups). (B) Numbers of IFNγ secreting and IL-17 secreting CD4+ T cells in lymph nodes from the indicated 38 week old mice (representative flow cytometric plots shown alongside). (C) CXCR5+PD-1+BCL-6+ follicular T helper (Tfh) cells and (D) CD19+CD95+PNA+ germinal center B (GC B) cells in 38 week old WT, WT→WT, Sle123→WT, Sle123→ApoA-I−/− and Sle123→ApoA-Itg mice. (n=6) (All data mean ± SD, ‡p<0.05 by one way ANOVA compared to WT and WT→WT control groups, *p<0.05 by one way ANOVA within Sle123 BMT group).

Similarly to a previous study in SLE-prone gld mice (18), plasma HDL-C levels, mApoA-I and PON-1 activity were reduced as a result of autoimmunity in Sle123→WT mice (Figure 1B–D, Supplemental Figure IA–B, and Table II). Indeed, reductions in plasma HDL-C in autoimmune Sle123→WT mice were inversely related to certain parameters of autoimmunity, including anti-dsDNA autoantibodies and CD4+ T cell activation (Supplemental Figure ID). Autoimmune mediated reduction of endogenous mApoA-I was also seen in Sle123→ApoA-Itg animals (Figure 1D–E and Supplemental Figure IA–B).

Interestingly, we observed effects of ApoA-I deficiency in control non-autoimmune WT BMT mice, including elevations in plasma PON-1 activity (↑57%) (Figure 1C and Table II) and an approximately 5-fold increase in numbers of lymph node B cells (Figure 2B). CD4+ T cells were increased in WT→ApoA-I−/− mice (3-fold) and non-BMT ApoA-I−/− mice (2-fold) (Figure 3B) compared to their WT counterparts, suggesting this was an intrinsic property of ApoA-I−/− mice. However, CD4+ lymphocyte expansion associated with the development of autoimmunity obscured this phenotype in Sle123 BMT mice (Figure 3B). In WT→ApoA-Itg animals, we observed slightly increased plasma HDL-C (↑14%) and higher PON-1 activity (↑52%) compared to their control non-BMT ApoA-Itg counterparts (Figure 1B–C and Table II).

Reduced Th1 and Tfh cells in Sle123→ApoA-Itg mice

Because the reduction in CD4+ T cells in Sle123→ApoA-Itg mice was relatively mild (38%↓), we reasoned that it might reflect a suppressive effect on the activation and/or differentiation of select CD4+ T cell populations, as opposed to a generalized reduction in all CD4+ cells. Interferon-γ secreting Th1 cells, but not IL-17 secreting Th17 cells, were reduced by half in Sle123→ApoA-Itg mice (Figure 4B). CD4+CXCR5+PD1+BCL6+ Tfh cells provide help to B cells for germinal center (GC) B cell formation and antibody production in response to foreign antigens as well as for pathogenic autoantibody production in SLE (33). Tfh cells were also significantly reduced in Sle123→ApoA-Itg mice (↓65%) (Figure 4C). Consistent with their role in GC formation (33), reduced Tfh cells resulted in lower numbers of GC B cells (↓47%) (Figure 4D). Again, ApoA-I deficiency did not result in opposite effects to those in ApoA-Itg mice. In addition, immune suppressive effects of ApoA-I were mediated independently of changes in the numbers of CD4+FoxP3+ regulatory T cells (data not shown). Finally, although ApoA-I was shown to modulate CD11c+ DC lymph node migration in hypercholesterolemic settings as measured by a FITC skin painting assay (34), we did not observe any difference in CD11c+ DC migration between WT, ApoA-I−/− and ApoA-Itg mice using the same assay (Supplemental Figure IIA).

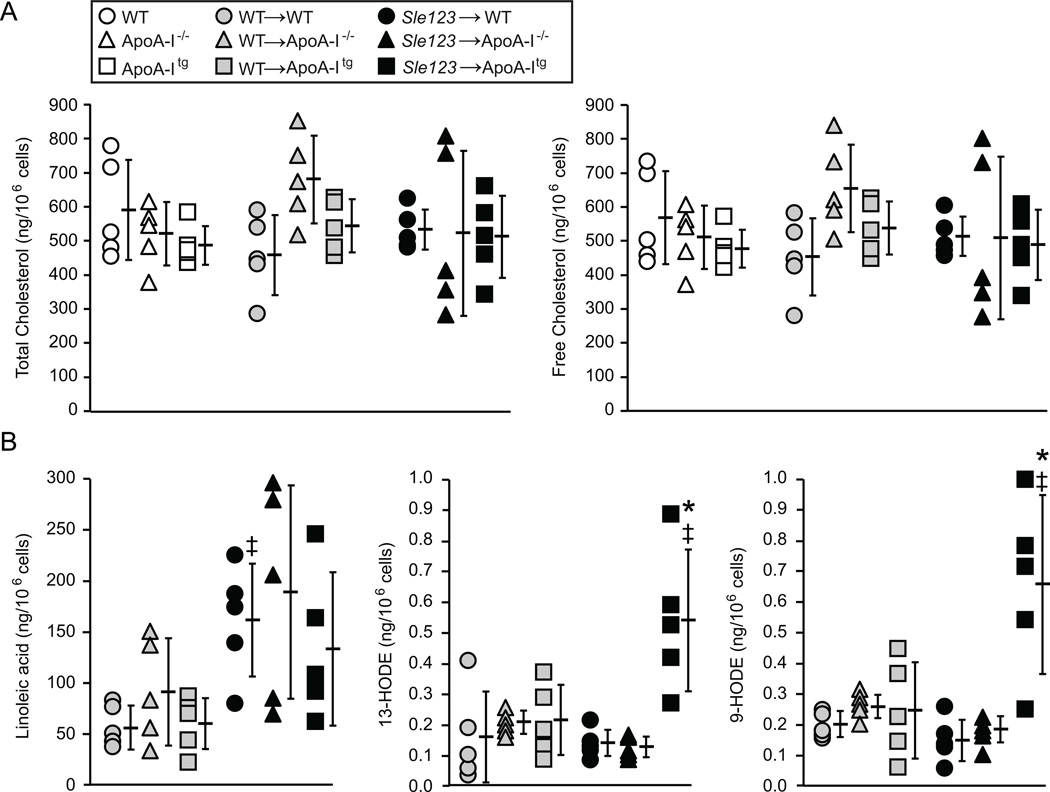

Immune suppressive action of ApoA-I is associated with modulation of cellular oxidized lipids but not cholesterol

ApoA-I deficiency in hypercholesterolemic mouse models and causes systemic autoimmunity by promoting lymphocyte cholesterol accumulation, resulting in modulation of lipid raft dependent antigen receptor-mediated activation (2, 8, 10, 11, 35). Conversely, increasing ApoA-I in hypercholesterolemic mice may regulate antigen receptor-mediated lymphocyte activation by reducing cellular cholesterol to modulate lipid rafts and antigen receptor activation in the opposite direction (2, 8, 35). However, cholesterol levels in lymphocytes from autoimmune and control WT, ApoA-I−/− and ApoA-Itg mice were not significantly different as measured by GC-MS (Figure 5A). Thus, immune suppression by ApoA-I in normocholesterolemic SLE mice was independent of changes in lymphocyte cholesterol homeostasis.

Figure 5.

(A) Immune suppression in Sle123→ApoA-Itg mice is not associated with reduced lymphocyte cholesterol content. Total (free plus esterified) and free cholesterol content of lymphocytes from the indicated control, WT BMT and Sle123 BMT mice (mean ±SD, n=5). (B) Levels of the indicated HODEs and linoleic acid in lymphocytes from the indicated WT BMT and Sle123 BMT mice (All data mean ± SD, n=5). Note that increases in lymphocyte 13-HODE and 9-HODE levels in Sle123→ApoA-Itg mice are not simply due to elevated levels of its precursor, linoleic acid. (‡p<0.05 by T test compared to control non-BMT, *p<0.05 by one way ANOVA within Sle123 BMT group).

HODEs and HETEs derived from 12/15-LO enzymatic and ROS-mediated oxidation of linoleic and arachidonic acids respectively have been widely used as measures of oxidative stress (36, 37) and the reduction of their levels in plasma and tissues has been used as a surrogate measure of the anti-inflammatory action of ApoA-I in hypercholesterolemic rodent models (5, 7). Surprisingly, ApoA-I mediated immune suppression in Sle123→ApoA-Itg mice was associated with increased lymphocyte levels of 13-HODE and 9-HODE (Figure 5B). Linoleic acid was not significantly different between WT, ApoA-I−/− and ApoA-Itg animals (Figure 5B), suggesting that the increases in 13-HODE and 9-HODE were not simply due to higher precursor fatty acid levels. Lymphocyte levels of 5-HETE, 12-HETE, 15-HETE and their precursor, arachidonic acid, were not significantly different between WT, ApoA-I−/− and ApoA-Itg mice (data not shown).

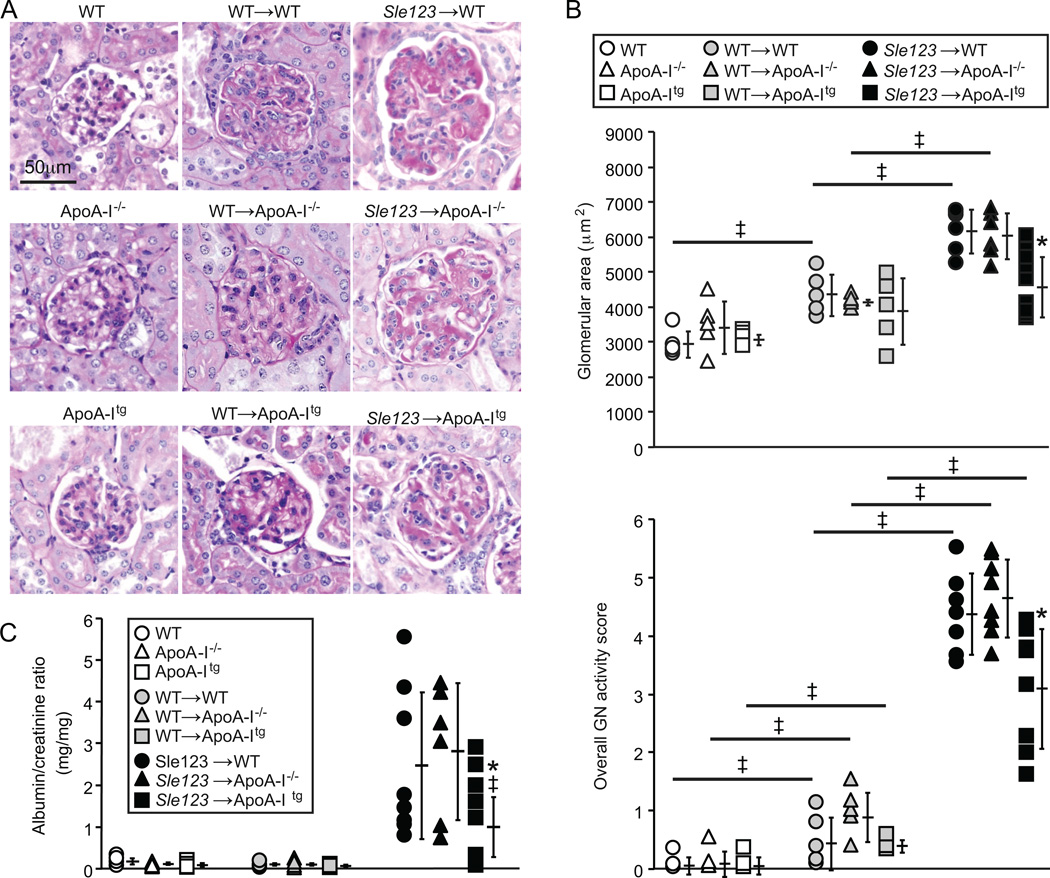

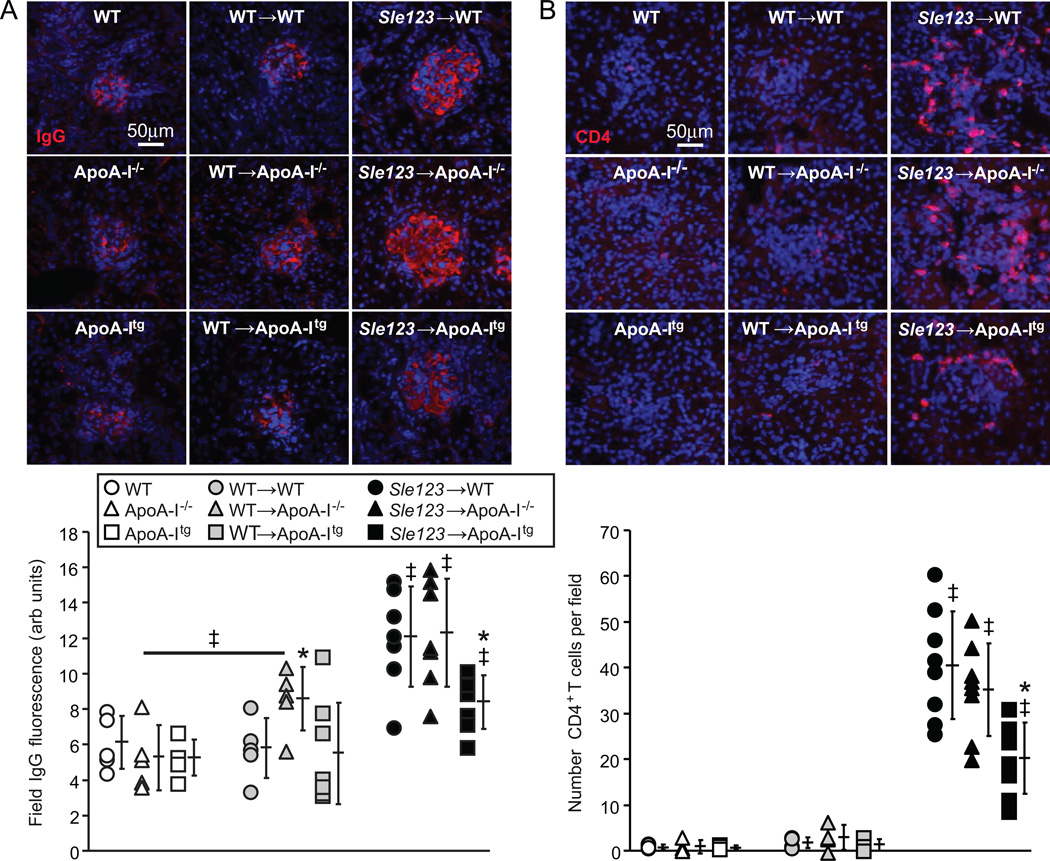

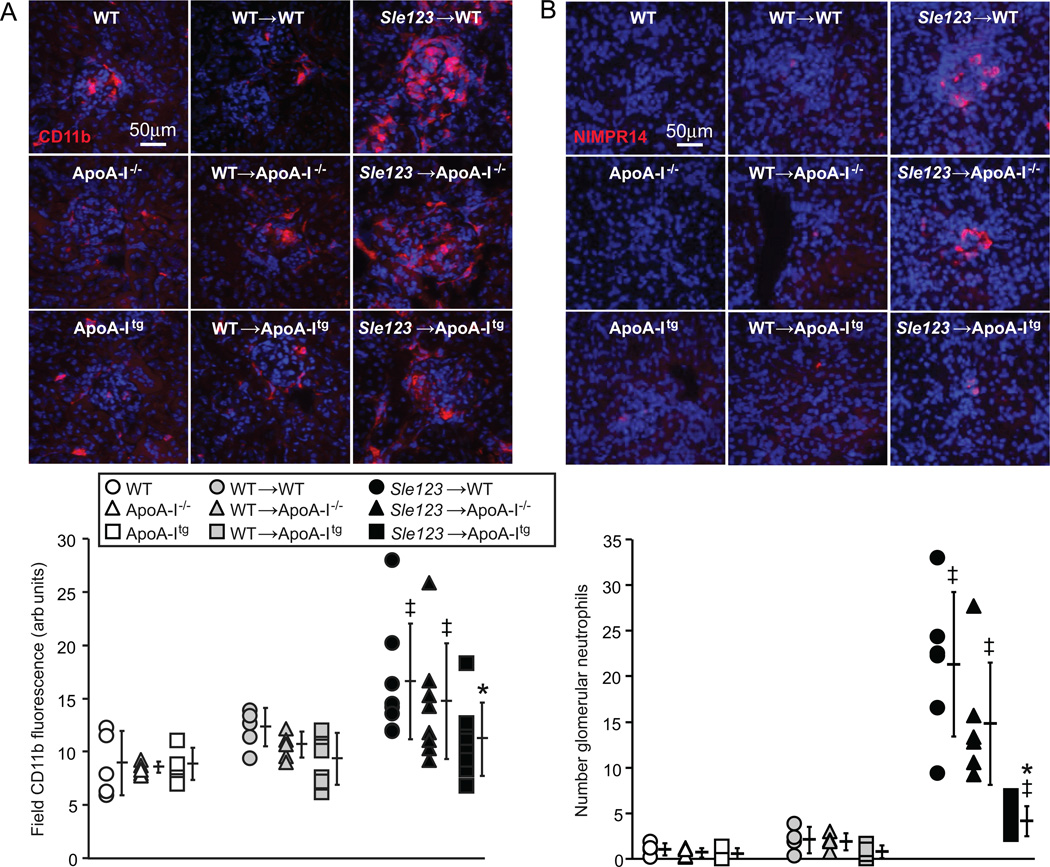

ApoA-I improves glomerulonephritis in Sle123 BMT mice

Glomerulonephritis (GN) was significantly improved in autoimmune Sle123→ApoA-Itg mice but not exacerbated in their Sle123→ApoA-I−/− counterparts (Figure 6). Histological analysis of glomeruli from control and BMT groups showed significant increases in glomerular area and overall GN activity scores in Sle123 BMT mice compared to their control non-BMT and control WT BMT counterparts (Figure 6A–B). These measures of GN were significantly improved in Sle123→ApoA-Itg mice, while ApoA-I deficiency had no significant effect on GN (Figure 6A–B). GN scores were also moderately increased in control WT BMT groups compared to their control non-BMT counterparts (Figure 6B), reflecting deleterious effects of lethal irradiation and/or BM reconstitution on renal pathology. Albuminuria in Sle123→ApoA-Itg mice was slightly reduced, but this was only statistically significant in a pair-wise comparison with Sle123→WT animals (p=0.052 by one-way ANOVA between the three Sle123 BMT groups) (Figure 6C). Improvement of GN in Sle123→ApoA-Itg mice was associated with marked reductions in glomerular IgG deposition (Figure 7A), consistent with the lower plasma autoantibodies in these animals (Figure 2A). Numbers of kidney infiltrating CD4+ T cells (Figure 7B), CD11b+ cells and NIMPR4+ neutrophils (Figure 8A–B) were also reduced in Sle123→ApoA-Itg mice, consistent with reduced renal inflammation.

Figure 6.

Protection against glomerulonephritis (GN) in Sle123→ApoA-Itg mice. (A) Periodic Acid Schiff (PAS) stained kidney sections showing representative glomeruli from the indicated 38 week old non-BMT control, control WT BMT and Sle123 BMT mice. (B) Average glomerular area (upper panel) and overall GN histological scores lower panel) in the indicated control (n=5), control BMT (n=5) and Sle123 BMT (n=6) groups (9 glomeruli scored per mouse) (‡p<0.05 by T test compared to indicated control, *p<0.05 by one way ANOVA within Sle123 BMT group). (C) Increases in urine albumin/creatinine ratio (ACR) in the indicated 38 week-old control (n=4), control BMT (n=4) and Sle123 BMT (n=6–8) animals (all data mean ± SD) (*p=0.052 by one way ANOVA, ‡p=0.049 compared to Sle123→WT by T test).

Figure 7.

Reduced glomerular IgG deposition and renal CD4+ T lymphocyte infiltration in Sle123→ApoA-Itg mice. Representative anti-IgG (A) and CD4 (B) stained kidney sections from the indicated 38 week old control (n=5), control WT BMT (n=5) and Sle123 BMT (n=7–8) mice. Graphs below show glomerular IgG immunofluorescence staining intensity and CD4+ T cell numbers in the indicated mice (*p<0.05 by one way ANOVA within its control or BMT group, ‡p<0.05 by T test compared to both non-BMT and BMT control groups of the same host genotype, or non-BMT control group as indicated). Each data point represents the average of 9 glomeruli per mouse.

Figure 8.

Reduced renal CD11b+(A) and NIMPR14+ neutrophil (B) inflammatory cell infiltration in Sle123→ApoA-Itg mice. Representative CD11b and NIMPR14 stained kidney cryosections from the indicated 38 week old control, control WT BMT and Sle123 BMT mice. Graphs below shows CD11b staining intensity and NIMPR14+ neutrophil numbers in the indicated mice (*p<0.05 by one way ANOVA within its control or BMT group, ‡p<0.05 by T test compared to non-BMT control mice of the same host genotype). Each data point represents the average of 9 glomeruli per mouse.

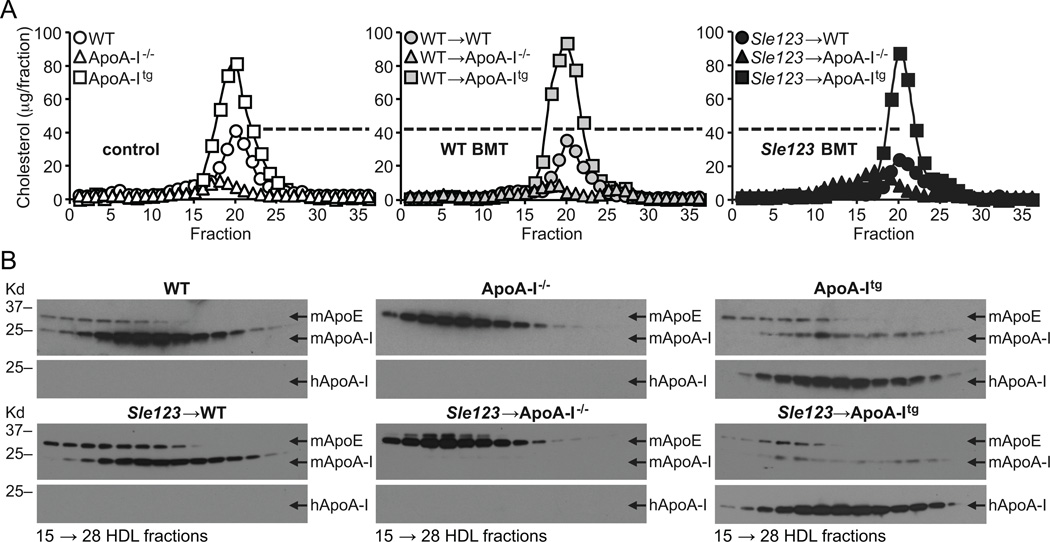

The lack of a potentiating effect of ApoA-I deficiency on autoimmunity may be due to compensatory increases in HDL ApoE

We reasoned that the absence of an exacerbatory effect of ApoA-I deficiency on autoimmunity in Sle123→ApoA-I−/− mice might be due to compensatory modifications of other major apolipoproteins on HDL in the absence of ApoA-I (29, 38). Like ApoA-I, ApoE can bind cholesterol and oxidized lipids and promotes cholesterol transport (39). Plasma levels of ApoE (Supplemental Figure IA and C) and ApoE levels on fast performance liquid chromatography (FPLC) separated HDL fractions (Figure 9B) were significantly increased in ApoA-I−/− mice. ApoA-II, on the other hand, was present at low levels in all mice (Supplemental Figure IA and C), consistent with the very low levels of this apolipoprotein in the C57Bl/6J strain (40). Thus, compositional changes on HDL in ApoA-I−/− mice that compensate for the loss of those functions of ApoA-I that mediate immune suppression include increased ApoE.

Figure 9.

(A) Cholesterol content of fast performance liquid chromatographically (FPLC) separated plasma lipoproteins from the indicated 38 week old mice (FPLC fraction number on x-axis). (B) Representative anti-mouse ApoA-I (mApoA-I), anti-mouse ApoE (mApoE) and anti-human ApoA-I (hApoA-I) western blots of FPLC HDL fractions shown below. Note reduction in HDL mApoA-I in Sle123→WT mice compared to their control WT counterparts (left panels in B). Note marked increases in HDL mApoE content in ApoA-I−/− mice and reductions in HDL mApoA-I content in ApoA-Itg mice. Data are representative of 3 independent experiments.

DISCUSSION

Using a normocholesterolemic murine SLE bone marrow transfer model, we found that increasing ApoA-I levels through transgenic human ApoA-I expression suppressed lymphocyte activation, reduced pathogenic interferon-γ secreting CD4+ Th1 cells and Tfh cells, lowered GC B cell numbers and autoantibody production, and improved GN. However, it did not reduce the effects of Sle123 induced autoimmunity to zero. Protection against SLE-mediated GN in Sle123→ApoA-Itg mice was associated with reductions in kidney infiltrating CD4+ T cells (Figure 7B) as well as lower CD11b+ monocytic and NIMPR14+ neutrophil infiltrates (Figure 8). Although reduced levels of autoantibodies leading to less glomerular IgG deposition could be responsible for this reduced renal inflammation (Figures 2A and 7A), direct anti-inflammatory action of ApoA-I may also be a major contributing mechanism, a possibility that could be addressed using a non-autoimmune anti-glomerular basement membrane (GBM) antibody-mediated nephritis model (41).

Other immune processes previously shown to be modified by ApoA-I in hypercholesterolemic mice, such as CD4+FoxP3+ Treg generation (42) (data not shown) or CD11c+ DC migration (Supplemental Figure IIA) (34), were unaffected in this normocholesterolemic model. Unlike in hypercholesterolemic mice (8), ApoA-I deficiency did not result in opposite effects on autoimmunity and modulation of ApoA-I did not affect immune cell cholesterol levels (Figure 5A). Taken together, these results show that potentiating effects of hypercholesterolemia on lymphocyte activation (and possibly other immune mechanisms) are required in order for ApoA-I to become important for preventing systemic autoimmunity (8) and that a function of ApoA-I other than cholesterol transport is the major mechanism accounting for its immune suppressive action in normal mice. However, it is possible that spatial rather than quantitative changes of cholesterol in lymphocyte membrane rafts might play a role.

Other than cholesterol transport and maintenance of cellular cholesterol homeostasis, “anti-oxidant” properties of HDL involving ApoA-I-mediated removal and PON1-mediated hydrolysis of atherogenic oxidized lipids contribute to its anti-inflammatory action in hypercholesterolemic atherosclerosis models (1, 43). The major classes of oxidized lipids bound by ApoA-I include the oxidized metabolites of linoleic acid and arachidonic acid (HODEs and HETEs respectively) (7, 44). Although several HODE and HETE species can recapitulate pro-inflammatory effects of oxidized LDL on vascular cells (45–47), they may have different properties depending on the cell/tissue context and disease setting (48–50). Indeed, we did not observe increases in lymphocyte HODE and HETE levels with the development of autoimmunity in Sle123→WT mice, or their reduction with immune suppression by ApoA-I in Sle123→ApoA-Itg mice (Figure 5B) (data not shown for arachidonic acid and HETEs). Surprisingly, however, levels of the major oxidative metabolites of linoleic acid, 13-HODE and 9-HODE, were significantly higher in lymphocytes from autoimmune Sle123→ApoA-Itg animals and this was not due to higher precursor linoleic acid levels (Figure 5B). Concentrations of 13-HODE and 9-HODE in the plasma were not significantly different between Sle123→WT and Sle123→ApoA-Itg mice (Supplemental Figure IIC), suggesting that the higher levels of these oxidized fatty acids in immune cells from autoimmune Sle123→ApoA-Itg animals was probably not due to an increased circulating plasma pool in ApoA-Itg animals. Further work using flow sorted immune cell preparations in conjunction with chiral phase LC-MS approaches to distinguish (R)-HODEs versus (S)-HODEs will be useful to determine how augmenting ApoA-I levels increases lymphocyte 13-HODE and 9-HODE levels in SLE and why it does so only in the context of autoimmunity (control ApoA-Itg animals did not have the same increases; Figure 5B). Nevertheless, it is noteworthy that 13-HODE and 9-HODE are agonists for peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARγ), a ligand-dependent nuclear receptor expressed in multiple cell-types including T cells, B cells, macrophages and DCs (51, 52). Anti-inflammatory activities have been attributed to ligand-activated PPARγ, including suppression of T cell activation, proliferation, Th1 polarization and autoimmunity (51, 53–56). For example, 13-HODE can regulate T lymphocyte function by blocking T cell IL-2 production through PPARγ, reducing T cell differentiation and proliferation (53). Higher levels of PPARγ have been reported in SLE lymphocytes (57) and PPARγ agonist treatment of T cells from SLE patients induces transcriptional repression of genes involved in T cell activation, with those related to Th1 differentiation most affected (58). Mice lacking PPARγ only in CD4+ T cells develop an autoimmune phenotype characterized by expansion of Tfh cells, resulting in increased GC B cells, production of anti-DNA autoantibodies, and glomerular inflammation (59). Based on our finding that Th1 and Tfh cells are reduced in Sle123→ApoA-Itg mice (Figure 4B–C), it is possible that PPARγ activation by 13-HODE and/or 9-HODE in lymphocytes may be a mechanism for ApoA-I mediated immune suppression, reducing T cell activation and subsequent expansion of Th1 and Tfh CD4+ T cells. Indeed, effects of ApoA-I on the lipid environment of CD4+ T lymphocytes and other immune cell-types in SLE may have a significant influence over the repertoire of transcription factors and cytokine signals that control CD4+ T cell differentiation into Th and effector subsets (33, 60). It is therefore important to determine whether 13-HODE and 9-HODE are generated intrinsically by the lymphocytes themselves or if they are derived from nearby innate immune cells such as macrophages which have been reported to produce these oxylipids in response to inflammatory stimuli through 12/15-LO enzyme activation to inhibit T cell activation and differentiation through PPARγ (53).

Immune suppression by ApoA-I occurred despite the predisposition of animals to developing reduced HDL-C and ApoA-I levels (see Sle123→WT in Figure 1B and D–E, Supplemental Figure IA–B and Figure 9B), and lower HDL-associated PON-1 activity (see Sle123→WT in Figure 1C). Indeed, there was a significant inverse correlation between HDL-C levels in autoimmune Sle123→WT mice and certain parameters of autoimmunity, including anti-dsDNA autoantibodies and CD4+ T lymphocyte activation (Supplemental Figure ID), reflecting autoimmune-mediated HDL reduction as previously described in normocholesterolemic gld mice (18). This is an important finding because it suggests that the predisposition of SLE to lower HDL/ApoA-I levels and PON-1 activity (16) may not necessarily make it refractory to immune suppressive or anti-inflammatory therapeutic strategies targeting ApoA-I, including ApoA-I mimetic peptides (14). Furthermore, autoimmune-mediated reductions in ApoA-I such as those observed in Sle123→WT animals are considered not only to contribute to premature atherosclerosis in lupus patients (61, 62), but also to amplify lymphocyte activation and autoimmunity itself (8, 10). However, unlike in the setting of hypercholesterolemia (8), we found no evidence for an exacerbatory effect of ApoA-I deficiency on any parameter of autoimmunity (something that would be expected if autoimmune mediated HDL reduction and dysfunction amplified autoimmunity itself). Similarly, because ApoA-I is important for stabilizing PON-1 activity on HDL particles (31), PON-1 activity was about 3-fold lower in ApoA-I−/− mice compared to their WT counterparts (Figure 1C), yet this did not affect autoimmunity. Therefore, our cumulative data suggest that autoimmune-mediated reductions in ApoA-I (HDL) levels and PON-1 activity in SLE patients (61, 63) may not necessarily amplify autoimmunity and inflammation. However, it remains to be determined to what extent the higher PON-1 activity in ApoA-Itg mice contributed to the observed immune suppressive and anti-inflammatory effects of increased ApoA-I in our study.

ApoA-I deficiency is pro-inflammatory and can promote systemic autoimmunity in hypercholesterolemic mouse models by deregulating lymphocyte cholesterol homeostasis to promote lymphocyte activation (8, 10, 11, 15). The absence of a significant effect of ApoA-I deficiency on any parameter of autoimmunity measured (Figures 2–4) may therefore seem surprising based on the immune suppressive effects of transgenic human ApoA-I expression that we observed in the same mouse SLE model system. While it will be important to rule out possible species differences in mouse versus human ApoA-I in this and other autoimmune models, it is noteworthy that compositional alterations compensating for ApoA-I deficiency may have contributed to a lack of any potentiating effect of ApoA-I deficiency on autoimmunity. For example, we found marked increases in the ApoE content of HDL in ApoA-I−/− mice (Supplemental Figure IA and C and Figure 9B) which may have compensated for the loss of important ApoA-I functions involved in immune suppression such as lipid binding, but not maintenance of PON-1 activity on HDL (31) considering the markedly lower HDL-associated PON-1 activity in ApoA-I−/− animals (Figure 1C).

Bioactive lipid mediators with established immune regulatory roles that are bound and carried by HDL, such as sphingosine-1-phosphate (S-1-P), also warrant investigation with respect to mechanisms of ApoA-I mediated immune suppression and anti-inflammatory action in SLE (2, 64, 65). Furthermore, the ability of HDL to modulate lipid homeostasis can affect immunity and renal inflammation through Toll-like receptors (TLRs) (66), perhaps even those mediating aberrant recognition of nucleic acids leading to pathogenic autoantibody production in SLE like TLR7 and TLR9 (67). It will therefore be important to perform broader lipidomic profiling in order to identify lipid metabolites that are associated with immune suppressive and anti-inflammatory actions of ApoA-I, as some of these are likely to be viable targets for therapeutic development. In this respect, it will be important to determine whether oxidative changes to which ApoA-I is inherently susceptible in chronic inflammatory settings such as SLE may be limiting its immunosuppressive potential such that using mutant forms of ApoA-I resistant to oxidative loss of function (68) may provide the most robust platform for these lipidomic approaches. Future studies characterizing the lipidome in tissues from autoimmune animal models with experimentally manipulated ApoA-I levels, HDL composition, or treated with apolipoprotein mimetic peptides, could therefore be used to identify novel lipid-based mechanisms of immune suppression and anti-inflammatory action in SLE.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the UAB Animal Resources Program Comparative Pathology Laboratory for histological slide preparation, the UAB-UCSD O'Brien Center for Acute Kidney Injury Research (P30 DK079337) for creatinine measurements and Dr. Mike Thomas of the Mass Spectrometer Facility of the Comprehensive Cancer Center of Wake Forest School of Medicine for lymphocyte cholesterol analysis. We thank Dr. Srinu Reddy (Department of Medicine, UCLA) for helpful advice on HODE/HETE LC-MS/MS. We thank Dr. Keiichi Higuchi (Shinshu University, Japan) for generously providing the anti-ApoA-II serum. We are also grateful to Dr. Beatriz Leon-Ruiz (Department of Microbiology, UAB) for advice on T follicular helper and germinal center B cell flow cytometric analyses and Dr. David Redden (Department of Biostatistics, UAB) for assistance with statistical analyses.

This work was supported by a Novel Research Project in Lupus from the Lupus Research Institute to JHK, T32 HL007918 to LLB and the UAB/UCSD O'Brien Core Center for Acute Kidney Injury Research (NIH P30 DK 079337). The AB Sciex 4000 Qtrap mass spectrometer was purchased with funds from a NIH Shared Instrumentation grant to SB (S10 RR19231). The Mass Spectrometer Facility of the Comprehensive Cancer Center of Wake Forest School of Medicine is supported in part by NCI center grant 5P30CA12197 and the Finnigan TSQ Quantum XLS mass spectrometer was funded by NIH Shared Instrumentation Grant 1S10RR027940.

Abbreviations used in this article

- ApoA-I

apolipoprotein A-I

- ApoE

apolipoprotein E

- ApoA-II

apolipoprotein A-II

- GC B cell

germinal center B cell

- GC-MS

gas chromatography mass spectrometry

- GN

glomerulonephritis

- HDL

high-density lipoprotein

- HETE

hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid

- HODE

hydroxyoctadecadienoic acid

- LC-MS

liquid chromatography mass spectrometry

- LO

lipoxygenase

- PON-1

paraoxonase-1

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- Tfh cell

follicular helper T cell

- WT

wild-type

REFERENCES

- 1.Lewis GF, Rader DJ. New insights into the regulation of HDL metabolism and reverse cholesterol transport. Circ. Res. 2005;96:1221–1232. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000170946.56981.5c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sorci-Thomas MG, Thomas MJ. High density lipoprotein biogenesis, cholesterol efflux, and immune cell function. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2012;32:2561–2565. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.112.300135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Westerterp M, Bochem AE, Yvan-Charvet L, Murphy AJ, Wang N, Tall AR. ATP-binding cassette transporters, atherosclerosis, and inflammation. Circ. Res. 2014;114:157–170. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.114.300738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhu X, Parks JS. New roles of HDL in inflammation and hematopoiesis. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 2012;32:161–182. doi: 10.1146/annurev-nutr-071811-150709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Navab M, Reddy ST, Anantharamaiah GM, Hough G, Buga GM, Danciger J, Fogelman AM. D-4F–mediated reduction in metabolites of arachidonic and linoleic acids in the small intestine is associated with decreased inflammation in low-density lipoprotein receptor-null mice. J. Lipid Res. 2012;53:437–445. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M023523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Folcik VA, Nivar-Aristy RA, Krajewski LP, Cathcart MK. Lipoxygenase contributes to the oxidation of lipids in human atherosclerotic plaques. J. Clin. Invest. 1995;96:504–510. doi: 10.1172/JCI118062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Imaizumi S, Grijalva V, Navab M, Van Lenten BJ, Wagner AC, Anantharamiah GM, Fogelman AM, Reddy ST. L-4F differentially alters plasma levels of oxidized fatty acids resulting in more anti-inflammatory HDL in mice. Drug Metab Lett. 2010;4:139–148. doi: 10.2174/187231210791698438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wilhelm AJ, Zabalawi M, Grayson JM, Weant AE, Major AS, Owen J, Bharadwaj M, Walzem R, Chan L, Oka K, Thomas MJ, Sorci-Thomas MG. Apolipoprotein A-I and its role in lymphocyte cholesterol homeostasis and autoimmunity. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2009;29:843–849. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.108.183442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bensinger SJ, Bradley MN, Joseph SB, Zelcer N, Janssen EM, Hausner MA, Shih R, Parks JS, Edwards PA, Jamieson BD, Tontonoz P. LXR signaling couples sterol metabolism to proliferation in the acquired immune response. Cell. 2008;134:97–111. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.04.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gonzalez NA, Bensinger SJ, Hong C, Beceiro S, Bradley MN, Zelcer N, Deniz J, Ramirez C, Diaz M, Gallardo G, de Galarreta CR, Salazar J, Lopez F, Edwards P, Parks J, Andujar M, Tontonoz P, Castrillo A. Apoptotic cells promote their own clearance and immune tolerance through activation of the nuclear receptor LXR. Immunity. 2009;31:245–258. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.06.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Feng H, Guo L, Wang D, Gao H, Hou G, Zheng Z, Ai J, Foreman O, Daugherty A, Li XA. Deficiency of scavenger receptor BI leads to impaired lymphocyte homeostasis and autoimmune disorders in mice. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2011;31:2543–2551. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.111.234716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yvan-Charvet L, Pagler T, Gautier EL, Avagyan S, Siry RL, Han S, Welch CL, Wang N, Randolph GJ, Snoeck HW, Tall AR. ATP-binding cassette transporters and HDL suppress hematopoietic stem cell proliferation. Science. 2010;328:1689–1693. doi: 10.1126/science.1189731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Watson CE, Weissbach N, Kjems L, Ayalasomayajula S, Zhang Y, Chang I, Navab M, Hama S, Hough G, Reddy ST, Soffer D, Rader DJ, Fogelman AM, Schecter A. Treatment of patients with cardiovascular disease with L-4F, an apo-A1 mimetic, did not improve select biomarkers of HDL function. J. Lipid Res. 2011;52:361–373. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M011098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Getz GS, Reardon CA. The structure/function of apoprotein A-I mimetic peptides: an update. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes. 2014;21:129–133. doi: 10.1097/MED.0000000000000045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Woo JM, Lin Z, Navab M, Van Dyck C, Trejo-Lopez Y, Woo KM, Li H, Castellani LW, Wang X, Iikuni N, Rullo OJ, Wu H, La Cava A, Fogelman AM, Lusis AJ, Tsao BP. Treatment with apolipoprotein A-1 mimetic peptide reduces lupus-like manifestations in a murine lupus model of accelerated atherosclerosis. Arthritis Res Ther. 2010;12:R93. doi: 10.1186/ar3020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kiss E, Seres I, Tarr T, Kocsis Z, Szegedi G, Paragh G. Reduced paraoxonase1 activity is a risk for atherosclerosis in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2007;1108:83–91. doi: 10.1196/annals.1422.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McMahon M, Grossman J, Skaggs B, Fitzgerald J, Sahakian L, Ragavendra N, Charles-Schoeman C, Watson K, Wong WK, Volkmann E, Chen W, Gorn A, Karpouzas G, Weisman M, Wallace DJ, Hahn BH. Dysfunctional proinflammatory high-density lipoproteins confer increased risk of atherosclerosis in women with systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;60:2428–2437. doi: 10.1002/art.24677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Srivastava R, Yu S, Parks BW, Black LL, Kabarowski JH. Autoimmune-mediated reduction of high-density lipoprotein-cholesterol and paraoxonase 1 activity in systemic lupus erythematosus-prone gld mice. Arthritis Rheum. 2011;63:201–211. doi: 10.1002/art.27764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rubin EM, Ishida BY, Clift SM, Krauss RM. Expression of human apolipoprotein A-I in transgenic mice results in reduced plasma levels of murine apolipoprotein A-I and the appearance of two new high density lipoprotein size subclasses. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1991;88:434–438. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.2.434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Parks BW, Srivastava R, Yu S, Kabarowski JH. ApoE-dependent modulation of HDL and atherosclerosis by G2A in LDL receptor-deficient mice independent of bone marrow-derived cells. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2009;29:539–547. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.108.179937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Robbiani DF, Finch RA, Jager D, Muller WA, Sartorelli AC, Randolph GJ. The leukotriene C(4) transporter MRP1 regulates CCL19 (MIP-3beta, ELC)-dependent mobilization of dendritic cells to lymph nodes. Cell. 2000;103:757–768. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00179-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kevil CG, Hicks MJ, He X, Zhang J, Ballantyne CM, Raman C, Schoeb TR, Bullard DC. Loss of LFA-1, but not Mac-1, protects MRL/MpJ-Fas(lpr) mice from autoimmune disease. Am. J. Pathol. 2004;165:609–616. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63325-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.He X, Schoeb TR, Panoskaltsis-Mortari A, Zinn KR, Kesterson RA, Zhang J, Samuel S, Hicks MJ, Hickey MJ, Bullard DC. Deficiency of P-selectin or P-selectin glycoprotein ligand-1 leads to accelerated development of glomerulonephritis and increased expression of CC chemokine ligand 2 in lupus-prone mice. J. Immunol. 2006;177:8748–8756. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.12.8748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.de Vries B, Kohl J, Leclercq WK, Wolfs TG, van Bijnen AA, Heeringa P, Buurman WA. Complement factor C5a mediates renal ischemia-reperfusion injury independent from neutrophils. J. Immunol. 2003;170:3883–3889. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.7.3883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Parks BW, Black LL, Zimmerman KA, Metz AE, Steele C, Murphy-Ullrich JE, Kabarowski JH. CD36, but not G2A, modulates efferocytosis, inflammation, and fibrosis following bleomycin-induced lung injury. J. Lipid Res. 2013;54:1114–1123. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M035352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Young S, Struys E, Wood T. Quantification of creatine and guanidinoacetate using GC-MS and LC-MS/MS for the detection of cerebral creatine deficiency syndromes. Curr Protoc Hum Genet. 2007 doi: 10.1002/0471142905.hg1703s54. Chapter 17:Unit 17 13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Parks BW, Gambill GP, Lusis AJ, Kabarowski JH. Loss of G2A promotes macrophage accumulation in atherosclerotic lesions of low-density lipoprotein receptor-deficient mice. J. Lipid Res. 2005;46:1405–1415. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M500085-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nordskog BK, Reagan JW, Jr, St Clair RW. Sterol synthesis is up-regulated in cholesterol-loaded pigeon macrophages during induction of cholesterol efflux. J. Lipid Res. 1999;40:1806–1817. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang Y, Sawashita J, Qian J, Zhang B, Fu X, Tian G, Chen L, Mori M, Higuchi K. ApoA-I deficiency in mice is associated with redistribution of apoA-II and aggravated AApoAII amyloidosis. J. Lipid Res. 2011;52:1461–1470. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M013235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Basu SK, Ho YK, Brown MS, Bilheimer DW, Anderson RG, Goldstein JL. Biochemical and genetic studies of the apoprotein E secreted by mouse macrophages and human monocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 1982;257:9788–9795. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gaidukov L, Tawfik DS. High affinity, stability, and lactonase activity of serum paraoxonase PON1 anchored on HDL with ApoA-I. Biochemistry. 2005;44:11843–11854. doi: 10.1021/bi050862i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Walsh A, Ito Y, Breslow JL. High levels of human apolipoprotein A-I in transgenic mice result in increased plasma levels of small high density lipoprotein (HDL) particles comparable to human HDL3. J. Biol. Chem. 1989;264:6488–6494. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Craft JE. Follicular helper T cells in immunity and systemic autoimmunity. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2012;8:337–347. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2012.58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Angeli V, Llodra J, Rong JX, Satoh K, Ishii S, Shimizu T, Fisher EA, Randolph GJ. Dyslipidemia associated with atherosclerotic disease systemically alters dendritic cell mobilization. Immunity. 2004;21:561–574. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2004.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sorci-Thomas MG, Owen JS, Fulp B, Bhat S, Zhu X, Parks JS, Shah D, Jerome WG, Gerelus M, Zabalawi M, Thomas MJ. Nascent high density lipoproteins formed by ABCA1 resemble lipid rafts and are structurally organized by three apoA-I monomers. J. Lipid Res. 2012;53:1890–1909. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M026674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Waddington EI, Croft KD, Sienuarine K, Latham B, Puddey IB. Fatty acid oxidation products in human atherosclerotic plaque: an analysis of clinical and histopathological correlates. Atherosclerosis. 2003;167:111–120. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9150(02)00391-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Navab M, Reddy ST, Van Lenten BJ, Fogelman AM. HDL and cardiovascular disease: atherogenic and atheroprotective mechanisms. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2011;8:222–232. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2010.222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vaisar T, Pennathur S, Green PS, Gharib SA, Hoofnagle AN, Cheung MC, Byun J, Vuletic S, Kassim S, Singh P, Chea H, Knopp RH, Brunzell J, Geary R, Chait A, Zhao XQ, Elkon K, Marcovina S, Ridker P, Oram JF, Heinecke JW. Shotgun proteomics implicates protease inhibition and complement activation in the antiinflammatory properties of HDL. J. Clin. Invest. 2007;117:746–756. doi: 10.1172/JCI26206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Getz GS, Reardon CA. Apoprotein E as a lipid transport and signaling protein in the blood, liver and artery wall. J. Lipid Res. 2008 doi: 10.1194/jlr.R800058-JLR200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sontag TJ, Reardon CA. Polymorphisms of mouse apolipoprotein A-II alter its physical and functional nature. PLoS One. 2014;9:e88705. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0088705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Xie C, Sharma R, Wang H, Zhou XJ, Mohan C. Strain distribution pattern of susceptibility to immune-mediated nephritis. J. Immunol. 2004;172:5047–5055. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.8.5047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wilhelm AJ, Zabalawi M, Owen JS, Shah D, Grayson JM, Major AS, Bhat S, Gibbs DP, Jr, Thomas MJ, Sorci-Thomas MG. Apolipoprotein A-I modulates regulatory T cells in autoimmune LDLr−/−, ApoA-I−/− mice. J. Biol. Chem. 2010;285:36158–36169. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.134130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhang Y, Zanotti I, Reilly MP, Glick JM, Rothblat GH, Rader DJ. Overexpression of apolipoprotein A-I promotes reverse transport of cholesterol from macrophages to feces in vivo. Circulation. 2003;108:661–663. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000086981.09834.E0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Van Lenten BJ, Wagner AC, Jung CL, Ruchala P, Waring AJ, Lehrer RI, Watson AD, Hama S, Navab M, Anantharamaiah GM, Fogelman AM. Anti-inflammatory apoA-I-mimetic peptides bind oxidized lipids with much higher affinity than human apoA-I. J. Lipid Res. 2008;49:2302–2311. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M800075-JLR200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Patricia MK, Kim JA, Harper CM, Shih PT, Berliner JA, Natarajan R, Nadler JL, Hedrick CC. Lipoxygenase products increase monocyte adhesion to human aortic endothelial cells. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 1999;19:2615–2622. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.19.11.2615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Huber J, Furnkranz A, Bochkov VN, Patricia MK, Lee H, Hedrick CC, Berliner JA, Binder BR, Leitinger N. Specific monocyte adhesion to endothelial cells induced by oxidized phospholipids involves activation of cPLA2 and lipoxygenase. J. Lipid Res. 2006;47:1054–1062. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M500555-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Limor R, Sharon O, Knoll E, Many A, Weisinger G, Stern N. Lipoxygenase-derived metabolites are regulators of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma-2 expression in human vascular smooth muscle cells. Am. J. Hypertens. 2008;21:219–223. doi: 10.1038/ajh.2007.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wittwer J, Hersberger M. The two faces of the 15-lipoxygenase in atherosclerosis. Prostaglandins Leukot. Essent. Fatty Acids. 2007;77:67–77. doi: 10.1016/j.plefa.2007.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nicolaou A, Mauro C, Urquhart P, Marelli-Berg F. Polyunsaturated Fatty Acid-Derived Lipid Mediators and T Cell Function. Front Immunol. 2014;5:75. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2014.00075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kiss M, Czimmerer Z, Nagy L. The role of lipid-activated nuclear receptors in shaping macrophage and dendritic cell function: From physiology to pathology. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2013;132:264–286. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.05.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Choi JM, Bothwell AL. The nuclear receptor PPARs as important regulators of T-cell functions and autoimmune diseases. Mol. Cells. 2012;33:217–222. doi: 10.1007/s10059-012-2297-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kidani Y, Bensinger SJ. Liver X receptor and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor as integrators of lipid homeostasis and immunity. Immunol. Rev. 2012;249:72–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2012.01153.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yang XY, Wang LH, Mihalic K, Xiao W, Chen T, Li P, Wahl LM, Farrar WL. Interleukin (IL)-4 indirectly suppresses IL-2 production by human T lymphocytes via peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma activated by macrophage-derived 12/15-lipoxygenase ligands. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:3973–3978. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M105619200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kuhn H, O'Donnell VB. Inflammation and immune regulation by 12/15-lipoxygenases. Prog. Lipid Res. 2006;45:334–356. doi: 10.1016/j.plipres.2006.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Harris SG, Padilla J, Koumas L, Ray D, Phipps RP. Prostaglandins as modulators of immunity. Trends Immunol. 2002;23:144–150. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4906(01)02154-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Natarajan C, Bright JJ. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma agonists inhibit experimental allergic encephalomyelitis by blocking IL-12 production, IL-12 signaling and Th1 differentiation. Genes Immun. 2002;3:59–70. doi: 10.1038/sj.gene.6363832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Oxer DS, Godoy LC, Borba E, Lima-Salgado T, Passos LA, Laurindo I, Kubo S, Barbeiro DF, Fernandes D, Laurindo FR, Velasco IT, Curi R, Bonfa E, Souza HP. PPARgamma expression is increased in systemic lupus erythematosus patients and represses CD40/CD40L signaling pathway. Lupus. 2011;20:575–587. doi: 10.1177/0961203310392419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zhao W, Berthier CC, Lewis EE, McCune WJ, Kretzler M, Kaplan MJ. The peroxisome-proliferator activated receptor-gamma agonist pioglitazone modulates aberrant T cell responses in systemic lupus erythematosus. Clin. Immunol. 2013;149:119–132. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2013.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Park HJ, Kim DH, Choi JY, Kim WJ, Kim JY, Senejani AG, Hwang SS, Kim LK, Tobiasova Z, Lee GR, Craft J, Bothwell AL, Choi JM. PPARgamma Negatively Regulates T Cell Activation to Prevent Follicular Helper T Cells and Germinal Center Formation. PLoS One. 2014;9:e99127. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0099127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Weinmann AS. Regulatory mechanisms that control T-follicular helper and T-helper 1 cell flexibility. Immunol. Cell Biol. 2014;92:34–39. doi: 10.1038/icb.2013.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hahn BH. Should antibodies to high-density lipoprotein cholesterol and its components be measured in all systemic lupus erythematosus patients to predict risk of atherosclerosis? Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62:639–642. doi: 10.1002/art.27298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wilhelm AJ, Major AS. Accelerated atherosclerosis in SLE: mechanisms and prevention approaches. Int J Clin Rheumtol. 2012;7:527–539. doi: 10.2217/ijr.12.46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Tripi LM, Manzi S, Chen Q, Kenney M, Shaw P, Kao A, Bontempo F, Kammerer C, Kamboh MI. Relationship of serum paraoxonase 1 activity and paraoxonase 1 genotype to risk of systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54:1928–1939. doi: 10.1002/art.21889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Rivera J, Proia RL, Olivera A. The alliance of sphingosine-1-phosphate and its receptors in immunity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008;8:753–763. doi: 10.1038/nri2400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Koch A, Pfeilschifter J, Huwiler A. Sphingosine 1-phosphate in renal diseases. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 2013;31:745–760. doi: 10.1159/000350093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Catapano AL, Pirillo A, Bonacina F, Norata GD. HDL in innate and adaptive immunity. Cardiovasc. Res. 2014;103:372–383. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvu150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]