Abstract

Positive future expectations can facilitate optimal development and contribute to healthier outcomes for youth. Researchers suggest that internal resources and community-level factors may influence adolescent future expectations, yet little is known about the processes through which these benefits are conferred. The present study examined the relationship between contribution to community, neighborhood collective efficacy, purpose, hope and future expectations, and tested a mediation model that linked contribution to community and collective efficacy with future expectations through purpose and hope in a sample of 7th grade youth (N = 196; Mage = 12.39; 60% female; 40% African American; 71% economically disadvantaged). Greater collective efficacy and contribution to community predicted higher levels of hope and purpose. Higher levels of hope and purpose predicted more positive future expectations. Contribution to community and neighborhood collective efficacy indirectly predicted future expectations via hope. Implications of the findings and suggestions for future research are discussed.

Keywords: hope, purpose, neighborhood collective efficacy, community contribution

Adolescence is an important developmental period marked by considering and planning for the future (Nurmi, 1991). The way in which adolescents conceive their future can have profound and long-reaching effects on health and well-being. Theory and research suggests that positive future expectations can facilitate optimal development and a successful transition into adulthood (Arnett, 2000; Aronowitz, 2000; McDade et al., 2011; Nurmi, 1991; Schmid & Lopez, 2011; Schmid, Phelps, & Lerner, 2011). On the other hand, adolescents who anticipate a negative future are more likely to exhibit problem behavior (Dubow, Arnett, Smith, & Ippolito, 2001; Sipsma, Ickovics, Lin, & Kershaw, 2012, 2015; Stoddard, Zimmerman, & Bauermeister, 2011). Given the important correlates and effects of future expectations among youth, it is important to understand what promotes positive future expectations.

The Development of Future Expectations

Researchers have conceptualized future expectations in numerous ways. The present study conceptualizes future expectations as the extent to which one anticipates achieving specific positive outcomes or skills in the future (e.g., having a happy life; Wyman, Cowen, Work, & Kerley, 1993). Researchers have explored numerous factors associated with future expectations, including engagement in risk behaviors, negative peer influence, perceived parental support, and internal resources such as problem-solving efficacy (Dubow et al., 2001; Kerpelman, Eryigit, & Stephens, 2008; Kirk, Lewis, Lee, & Stowell, 2011; Sipsma et al., 2012). Researchers also suggest that future expectations may be vulnerable to external stressors. For example, exposure to community violence may alter adolescents’ perceptions of future opportunities and negatively impact academic aspirations (Lorion & Saltzman, 1993; McGee, 1984). Additionally, Sipsma et al. (2012) found that external factors (e.g., urbanicity) were related to expectations associated with risk behavior. Thus, the present study focused on both community and individual-level factors in relation to future expectations.

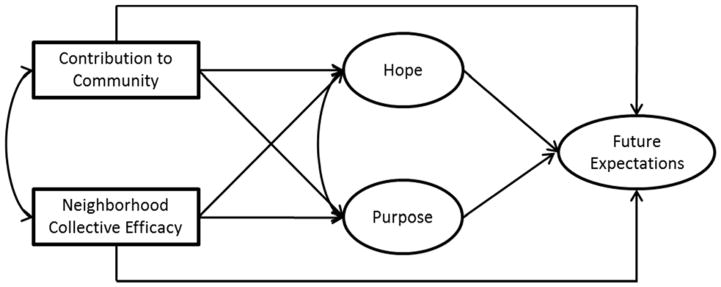

Seginer (2008) proposed a model in which perceptions of community-level factors (e.g., perceiving community violence as a challenge rather than a threat) influenced individuals’ thoughts about their future through the psychological asset of hope. We expand upon this model in two ways (See Figure 1). First, we aimed to take a promotive approach by examining whether community-oriented resources (i.e., contribution to community and neighborhood collective efficacy) and hope are associated with future expectations outside of potentially threatening situations. Although Seginer (2008) emphasized that hope is aroused only under adverse conditions, other researchers have explored these constructs in stable, nonthreatening conditions (e.g., Yarcheski, Scoloveno, & Mahon, 1994). Second, we considered the construct of purpose in addition to hope. As described below, both constructs are potentially relevant to positive future expectations. Each may be considered a fundamental aspect of motivation leading to positive future expectations and, ultimately, positive youth development (Bronk, Hill, Lapsley, Talib & Finch, 2009; Sun & Shek, 2012). In the sections that follow, we discuss the potential association between community-oriented resources and future expectations. We then propose mediation through the psychological assets of hope and purpose.

Figure 1.

Hypothesized model delineating relationship between contribution to community, neighborhood collective efficacy, hope, purpose and future expectations. All relationships are expected to be positive.

Community-Oriented Resources and Future Expectations

Contribution to community

Community contribution, or the process through which youth become involved in the community in order to help others and improve society in general, is an important factor that fosters positive youth development (Adler & Goggin, 2005; Youniss & Yates, 1997). Contributing to community efforts may provide opportunities for growth and realization of abilities and skills. Dubow et al. (2001) found that a sense of problem-solving efficacy was associated with higher positive future expectations and suggested that this may be due to “repeated successful employment of problem-solving skills [that] affirm the individual’s positive self-attributions and future expectations” (Dubow et al. 2001, p. 22). Thus, engaging in positive activities may promote internal resources. In addition, Evans (2007) found that adolescents who were engaged in community activities expressed feeling powerful and important, and increased power was associated with a sense of responsibility (Evans, 2007). Thus, working for change in the community can lead to a sense of control over the future and a desire to work toward positive outcomes.

Neighborhood collective efficacy

Neighborhood collective efficacy refers to “the linkage of mutual trust and the willingness to intervene for the common good” (Sampson, Raudenbush, & Earls, 1997, p. 919) that exists among individuals in a community. This sense of collective efficacy leads to informal social control, which is thereby associated with positive outcomes for youth in that community. To our knowledge, researchers have not investigated the relationship between neighborhood collective efficacy and positive future expectations. However, theory suggests that perceptions of one’s neighborhood, and collective efficacy in particular, may influence future expectations among adolescents (Leventhal & Brooks-Gunn, 2000). Mello and Swanson (2007) investigated the relationship between perceptions of neighborhood quality and domain specific future expectations (e.g., personal, educational, and occupational) in a sample of African American adolescents. They found that positive perceptions of the neighborhood (i.e., lower perceived prevalence of vandalism, drug use and employment) were associated with more optimistic occupational and educational expectations. Collective efficacy extends beyond these perceptions. Instead, collective efficacy may convey that community members are important to the overarching community itself and that individuals within that community are willing to promote the well-being of fellow members. Thus, it may provide social scaffolding for youth and increase the sense that they are valuable members of the community. Researchers also suggest that collective efficacy promotes increased prosocial behavior among community adolescents (O’Brien & Kauffman, 2013); prosocial behavior may, in turn, increase positive views of the self.

Community-Oriented Resources, Psychological Assets, and Positive Future Expectations

Hope

Snyder’s (2002) conceptualization of hope consists of conceived pathways to achieve goals (i.e., pathways), and agentic beliefs regarding one’s ability to achieve them (i.e., agency). Because we aimed to explore generalized notions of hope, we focused on the construct of agency, which is not necessarily dependent upon specific goals in the way that pathways are. The concept of agency is akin to self-efficacy (Snyder, 1995; Sun and Shek, 2012). Relevant to the present investigation, Seginer (2008) suggested that under conditions in which individuals’ resources are taxed (e.g., community violence), a sense of hope (i.e., the perception that one’s goals can be attained; Snyder et al., 1997) can lead to resilience and positive future expectations despite external challenges. The way youth consider their agentic abilities to attain goals can have a strong impact on how they perceive themselves fitting into the world around them and whether they seek and commit to overarching life aims (Snyder et al., 1997). According to Seginer (2008), when individuals can appraise difficulties as a challenge (as opposed to a threat), hope is fostered; hope, in turn, promotes the setting and pursuit of goals and sustains individuals’ confidence in their ability to achieve those goals (Seginer, 2008). Hope may also positively affect cognitions and emotions related to future expectations (Schmid & Lopez, 2011). Indeed, researchers have found that hope is associated with higher self-worth, perceived competence in various domains, life satisfaction, psychological well-being and academic achievement and lower internalizing disorders (Adelabu, 2008; Shorey, Little, Snyder, Kluck, & Robitschek, 2007; Snyder et al., 1997; Valle, Huebner, & Suldo, 2006).

According to Seginer (2008), “hope is aroused and maintained when individuals consider they have enough resources to meet situational demands” (pp. 278). However, Snyder (2002) suggests that, although hope is particularly relevant when challenges arise, “agency thinking is important in all goal-directed thought” (pp. 251). Thus, hope may be a dispositional construct that is relatively stable across situations (Synder, 1995). A generalized sense of agency may provide motivation by internalizing the idea that one’s resources are typically enough to meet challenges. As such, individuals may consider their future optimistically and see themselves as capable of overcoming any difficulties that may arise.

Hope for a positive future may be learned through one’s social relationships and physical environment (Lynch, 1965; McGee, 1984; Stotland, 1969). Negative environmental factors (e.g., exposure to community violence) are thought to inhibit the development of hope (Lorion & Saltzman, 1993; McGee, 1984). More recently, Sun and Shek (2012) suggested that hope results from past experiences, such that individuals who experience success and attribute it to controllable factors (e.g., effort) will be more likely to feel efficacious in achieving goals. As such, providing experiences for success is important in the development of hope. Furthermore, in a review of the literature on hope, Esteves, Scoloveno, Mahat, Yarcheski, and Scoloveno (2013) found that hope was significantly associated with social support, such that adolescents who experienced a strong social network reported higher hopes for the future. This suggests that adolescents who are embedded in a strong community may consequently feel greater control over attaining a positive future.

Purpose

Future expectations may also be associated with a sense of purpose in life. Purpose refers to overarching goals that have personal significance (George & Park, 2013), that provide a framework for lower-level goals and actions, and motivate an individual to allocate personal resources toward their actualization (McKnight & Kashdan, 2009). The field of positive youth development has identified purpose as a developmental asset and an indicator of thriving (Scales & Leffert, 1999). Purpose is important for health and well-being, and has been linked to higher positive affect, life satisfaction, and academic achievement, as well as lower negative affect and substance use (Burrow & Hill, 2011; Hill, Burrow, & Sumner, 2013; Padelford, 1974).

Although Seginer’s (2008) model only delineates the expected influence of hope on future expectations, purpose may also lead to more positive views of the future. It is possible that possessing an overarching and personally significant goal in life may lead an individual to be positive about one’s future. Like hope, which provides a motivating force through its relationship with efficacy and agency beliefs, purpose may motivate positivity regarding one’s future because it indicates that there is something to live for and look forward to (Bronk, 2014; Bronk et al., 2009; Schmid & Lopez, 2011). In other words, hope may provide information regarding “how,” while purpose provides information regarding “what.” Indeed, Bronk et al. (2009) found that purpose was highly correlated with hope, particularly the agentic aspect of hope, in a sample of adolescents. Furthermore, both of these constructs were positively associated with life satisfaction. The similar construct of optimism has been conceptualized as including both valued goals and confidence that the outcome will occur (sometimes through personal agency; Scheier & Carver, 1992; Sun & Shek, 2012). Previous research suggests that having something to live and strive for as indicated by a sense of purpose in life leads to a sense of well-being and positive orientation toward the future (for a review, see Bronk, 2014).

An individual’s sense of purpose may also be influenced by resources within the community. According to Kashdan & McKnight (2009), individuals who seek new experiences and actively “reflect on and integrate” (p. 308) this information into their sense of self will be more likely to develop a purpose in life. As such, activities that allow an opportunity to expand the sense of self and an orientation toward integrating information and projecting it into future conceptions of the self may aid in purpose development (Kashdan & McKnight, 2009). Furthermore, social interactions that provide opportunities to observe and model the behavior of others may also aid in purpose development. Individuals who are involved in community work (i.e., contribution to community) and who have an opportunity to witness positive collaboration and interactions among community members (i.e., neighborhood collective efficacy) may be more likely to endorse a purpose in life because they have engaged in meaningful activities and witnessed purposeful behavior enacted by and rewarded among close others (Bronk, 2014). For example, Schwartz, Keyl, Marcum, and Bode (2009) found that adolescents who engaged in altruistic behavior (e.g. helping family members) reported greater purpose in life. Furthermore, when youth become active within their community, they begin to understand themselves within a societal context, which allows them to better grasp the way they fit in beyond the scope of their family and friends (Erikson, 1968).

Present Study

The purpose of this study was to explore factors that may be associated with future expectations in a sample of 7th grade youth. More specifically, we examined the relationship between contribution to community, neighborhood collective efficacy, hope, purpose, and future expectations and tested a mediation model that linked contribution to community and neighborhood collective efficacy with future expectations through hope and purpose. We hypothesized that youth who reported greater contribution to community and neighborhood collective efficacy would report higher levels of hope and purpose and more positive future expectations. We also hypothesized that hope and purpose would mediate the relationship between contribution to community and neighborhood collective efficacy and future expectations. Although theory and research suggests that contribution to community, neighborhood collective efficacy, hope and purpose may positively influence adolescent future expectations (e.g., Bronk, 2014; Leventhal & Brooks-Gunn, 2000; Seginer, 2008), to our knowledge no researchers have explored these constructs concurrently to determine potential mediating processes.

Method

Participants

This study is based on data collected as part of a school-based survey focused on understanding risk and protective factors for youth violence and bullying. Data was collected from 7th grade students at a suburban Midwestern middle school during their health class. Though the school is located in a suburban neighborhood, the district cuts across both suburban and urban areas, making the student population highly diverse (50% African American, 36% White). In addition, this suburban community is located in a geographic area that has undergone significant economic decline and 71% of the 7th grade students at the time of survey administration were considered economically disadvantaged (Michigan Department of Education, 2014). Approximately 48% of eligible 7th grade students participated in the survey (n = 196; Mage = 12.39, SD = .52; 60% female). The sample was ethnically diverse with 45% African American, 27% White, and 21% Multiracial.

Procedure

Trained research staff administered the paper-pencil survey during students’ health class in the 2011–2012 academic year. The survey included items related to self-concept and identity, future expectations and other known risk and protective factors associated with youth violence, delinquency, and alcohol and other drug use and was completed within 45 minutes. Students that chose not to participate were provided with worksheets to complete during the class period. For participants with lower reading levels or limited English proficiency (n = 4), the survey was read aloud privately in a separate classroom.

Prior to students completing the survey, both written parental consent and student assent were obtained. Participation in the study was completely voluntary and no compensation was provided to participants. The study was approved by the University of Michigan Institutional Review Board and a Certificate of Confidentiality was obtained from the National Institutes of Health.

Measures

Future expectations

Four items were used to assess participants’ level of future expectations. Students were asked to indicate how much they agree or disagree with the following items: I will be able to handle the problems that might come up in my life, I will be able to handle my school work, I will have a happy life, and I will have interesting things to do in my life (α = .76; Wyman et al., 1993). Response options for each statement ranged from 1 (Disagree a lot) to 4 (Agree a lot).

Hope

Four items were used to assess hope-agency (or goal-directed hope) among participants. Students were asked to indicate how much they agree or disagree with the following items: I energetically pursue my goals, My past experiences have prepared me well for my future, I’ve been pretty successful in life so far, and I meet the goals I set for myself (α = .73; Snyder et al., 1997). Response options for each statement ranged from 1 (Disagree a lot) to 4 (Agree a lot).

Purpose

Three items were used to assess youth purpose among participants. Students were asked to indicate how much they agree or disagree with the following items: I have a purpose in my life that says a lot about who I am, I enjoy making plans for the future and working to make them a reality, and I have a purpose in my life that reflects who I am (α = .70; Ryff, 1989). Response options for each statement ranged from 1 (Disagree a lot) to 4 (Agree a lot).

Contribution to community

Three items were used to assess participants’ contribution to community. Students were asked to indicate how much they agree or disagree with the following items: I want to make a difference in the world, I currently contribute to my community, and It is important for me to contribute to my community (Shamah, 2011). Response options for each statement ranged from 1 (Disagree a lot) to 4 (Agree a lot). A mean contribution to community score was calculated for each participant with higher scores indicating a greater level of contribution to community (α = .65).

Neighborhood collective efficacy

The eight-item Neighborhood Collective Efficacy Scale was used to assess participants’ perception of social cohesion and trust within their neighborhood (Sampson & Raudenbush, 1999). Students were asked to indicate how much they agree or disagree with the following items: People in my neighborhood are willing to help their neighbors, I live in a neighborhood where people know and like each other, and There are adults in my neighborhood that I can look up to. A mean score was computed for each participant with higher scores indicating a higher level of collective efficacy within their neighborhood (α = .90).

Demographic characteristics

Participants reported their gender (0 = male; 1 = female) and race/ethnicity. Race/ethnicity was measured using six categories: Black or African American, White, Asian, American Indian, Hispanic, and Other. For analyses, race/ethnicity was recoded as 0 = non-White and 1 = White.

Data Analytic Strategy

Latent-variable structural equation modeling was completed in Mplus version 7.3 (Muthén & Muthén, 2012). We created a measurement model to assess whether our items were appropriate indicators of our latent constructs of hope, purpose, and future expectations. We then tested our full structural model which included direct paths from neighborhood collective efficacy and contribution to community to hope, purpose and future expectations. We also tested for indirect paths from neighborhood collective efficacy and contribution to community to future expectations via hope and purpose. Given the clustering effect that can occur between neighborhood collective efficacy and contribution to community, as well as hope and purpose, our model accounted for these correlations between variables’ error terms (r = .31 and r = .61, respectively). We considered the possibility of gender and/or racial differences in our constructs of interest and whether demographic characteristics should be included as indicators of individual constructs in the structural model. We used t-tests to determine if there were gender or race/ethnicity differences in our constructs of interest. No significant differences were found for gender, so for parsimony, gender was not included in the model. Race/ethnicity differences were found for hope (MWhite = 3.19, SD = .58; Mnon-White = 3.54, SD = .43; t(75.56) = 3.93, p < .05) and purpose (MWhite = 3.41, SD = .57; Mnon-White = 3.60, SD = .51; t(82.78)= 2.06, p < .05). Therefore, we accounted for those differences in our model. Due to our sample size, we were unable to explore gender or race/ethnicity differences in path coefficients. Missing data were handled with maximum likelihood (ML) estimation.

We evaluated our model fit based on the χ2 value, the Comparative Fit Index (CFI), the Tucker Lewis Index (TLI), and the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA). We also evaluated the statistical significance of structural paths and correlations. To assess the significance of indirect effects, we generated confidence intervals of the indirect effects. If the 95% confidence interval of the unstandardized specific indirect effect did not include 0, we concluded that there was a significant indirect effect. Consideration was given to potential model modifications suggested by the Lagrange multiplier tests for adding parameters and the Wald test for dropping parameters.

Results

Descriptive Data

Table 1 provides descriptive data for the focal variables (future expectations, hope, purpose, contribution to community and neighborhood collective efficacy). Correlations between study variables are also displayed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations of study variables

| Mean | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Future expectations | 3.61 | .47 | -- | |||

| 2. Hope | 3.44 | .50 | .57 | -- | ||

| 3. Purpose | 3.55 | .53 | .47 | .47 | -- | |

| 4. Contribution to community | 3.26 | .59 | .25 | .33 | .26 | -- |

| 5. Neighborhood collective efficacy | 3.10 | .74 | .34 | .32 | .29 | .32 |

Note. All correlations were significant at p < .01. Sample sizes ranged from 182 to 195.

Measurement Model

Our measurement model fit the data well (χ2 [38, N = 196] = 48.42, p = .12; TLI= .98, CFI = .98, RMSEA = .04). Factor loadings for the indictors of latent factors ranged from .48 to .77. This model indicated that hope was positively correlated with purpose and future expectations. Purpose and future expectations were also positively correlated.

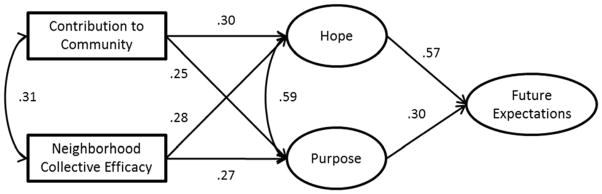

Structural Model

The results of our structural model are displayed in Figure 2. Our structural model fit the data well (χ2 [65, N = 193] = 76.12, p = .16; TLI= .98, CFI = .98, RMSEA = .03). We found that higher neighborhood collective efficacy and contribution to community were associated with higher purpose (β = .27, p < .01; β = .25, p < .01, respectively) and higher hope (β = .28, p < .01, β = .30, p < .01, respectively). Higher hope was associated with higher future expectations (β = .57, p < .001). In addition, higher purpose was associated with higher future expectations (β = .30, p < .04. As seen in Table 2, neighborhood collective efficacy was indirectly associated with future expectations through hope (unstandardized indirect effect = .08; 95% CI = .02, .14). Similarly, contribution to community was indirectly associated with future expectations through hope (unstandardized indirect effect = .10; 95% CI = .03, .18). Seventy-four percent of the relationship between contribution to community and future expectations was explained by the indirect effect through hope; 47% of the relationship between neighborhood collective efficacy and future expectations was explained by the indirect effect through hope.

Figure 2.

The effect of contribution to community and neighborhood collective efficacy on hope, purpose, and future expectations. Note. Standardized estimates are shown. Only significant paths are displayed (p < .05). Race/ethnicity was included as a covariate in estimation, but is not shown. Model fit (χ2 [65, N = 193] = 76.12, p = .16; TLI= .98, CFI = .98, RMSEA = .03).

Table 2.

Results of the Structural Model examining the relationships between contribution to community, collective efficacy, purpose, hope and future expectations (n = 193).

| Direct, Indirect, and Total Effects | b (SE) | Standardized Results | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct [95% CI] | Total Indirect [95% CI] | Total [95% CI] | ||

| Path coefficients of primary study variables | ||||

| Neighborhood collective efficacy→ Future expectations | .05 (.04) | .10[−.05, .25] | .24[.12, .37] | .34[.18, .50] |

| Contribution to community → Future Expectations | −.01 (.04) | −.02[−.16, .13] | .25 [.12, .37] | .23[.08, .38] |

| Neighborhood collective efficacy → Purpose | .14 (.05) | .27[.08, .46] | ||

| Contribution to community → Purpose | .16 (.06) | .25[.08, .42] | ||

| Neighborhood collective efficacy → Hope | .15 (.04) | .28 [.14, .43] | ||

| Contribution to community → Hope | .20 (.05) | .30 [.16, .44] | ||

| Hope → Future Expectations | .51 (.15) | .57 [.31, .83] | ||

| Purpose → Future Expectations | .28 (.15) | .30 [.01, .58] | ||

| Path coefficients of covariatea | ||||

| White → Purpose | −.19 (.07) | −.23[−.39, −.07] | ||

| White → Hope | −.30 (.07) | −.34 [−.47, −.21] | ||

| Variable correlations | ||||

| Hope ↔ Purpose | .06 (.02) | .59 [.40, .79] | ||

| Contribution to community ↔ Neighborhood collective efficacy | .13 (.03) | .31 [.18, .44] | ||

| Specific Indirect effect | Unstandardized | Standardized | ||

| Contribution to community → Hope → Future expectations | .10 [.03, .18] | .17 [.06, .29 ] | ||

| Collective Efficacy → Hope → Future expectations | .08 [.02, .14] | .16 [.05, .27] | ||

Note. CI indicates confidence interval. Significant effts are boldfaced. Only significant specific indirect effects are shown.

Covariate coded as White = 1; non-White = 0.

Discussion

Previous research has shown the importance of fostering positive future expectations among youth. Positive future expectations are associated with better well-being and fewer negative outcomes (Aronowitz, 2005; McDade et al., 2011; Schmid et al., 2011). This has called attention to factors that may be associated with positive expectations for the future among youth. Although previous research has provided insight on positive expectations among individuals who have experienced community disadvantage or life stressors (e.g., Seginer, 2008), we sought to expand previous work by focusing on promotive factors that exist regardless of external stressors. As such, we explored community-oriented resources and the positive psychological assets of hope and purpose. The present study found that positive future expectations are higher when collective efficacy in the community is high, youth are engaged in community activities, and youth report a sense of hope. Furthermore, the effect of community-oriented resources on positive future expectations appears to be mediated by hope.

Neighborhood collective efficacy and contribution to community were associated, suggesting that positive neighborhood factors may coincide. When individuals feel safe and valued in their community, they may be more willing to provide services to others in their community and work to enact beneficial change (O’Brien & Kauffman, 2013). In turn, contribing to one’s community may also promote social bonding and collective efficacy within a neighborhood (Collins, Neal & Neal, 2014). The way communities view youth can influence hope and purpose among adolescents. Hope may be associated with experiencing success and attributing it to one’s abilities (Sun & Shek, 2012). As such, contributing to the community and witnessing positive outcomes from this involvement may lead adolescents to recognize their agentic power. This sense of agency may then be transferred across situations. Hope has also been connected to social support (Esteves et al., 2013). Thus, communities that explicitly care for its members by demonstrating a willingness to intervene for the benefit of others may lead adolescents to recognize their importance and the presence of help and assistance when necessary. The link between community-oriented resources and purpose is also important to consider. Purpose is more likely to be developed for individuals who live in communities where youth are viewed in a positive light as resources to be developed (Benson, 2006). Similarly, communities that offer a variety of youth activities foster purpose (Damon, 2004). When youth are able to contribute to their community and are exposed to different activities and experiences, the opportunities to reflect on what is important to them is maximized. Furthermore, positive communities provide numerous opportunities to witness and model prosocial characteristics exhibited by valued community members.

Hope and purpose were positively associated, which coincides with previous research (Bronk et al., 2009). This finding lends credibility to the dual nature of these positive constructs. As such, agentic beliefs about one’s ability to achieve goals (i.e., hope) are necessarily accompanied by valued goals (Snyder, 1995; 2002). Hope provides motivation and energy to achieve goals, while purpose provides direction. Although we only considered a correlational relationship between hope and purpose, an alternative relationship may be possible. Namely, purpose may foster hope. As such, purpose may not only influence future expectations directly, but may provide influence through the construct of hope. This coincides with Snyder (1995), who suggested that hope could be fostered by clarifying one’s goals. According to Snyder (1995), goals that are perceived as possible can “unleash the person’s sense of energy to pursue the goal” (pp. 358). These findings are also similar to those of Bronk et al. (2009), who found that hope, particularly the agentic aspect of hope, mediated the relationship between purpose and life satisfaction among adolescents. The present findings suggest that this relationship may also exist for the outcome of positive future expectations. Having an overarching life goal can lead an individual to direct their energy toward relevant pursuits, recognize and foster their sense of agency to accomplish their goals, and ultimately look forward to a bright future (for a review, see Bronk, 2014). For example, having a purpose in life has been found to predict grit (i.e., persistence in working toward one’s goals) over the course of a college semester (Hill, Burrow, & Bronk, in press). These findings are relevant to the concept of hope, as they suggest that a purpose in life may foster a desire to persevere, overcome challenges, and build a sense of agency and self-efficacy.

The present study suggests that hope is associated with positive future expectations, and mediates the relationship between positive community-oriented resources and future expectations. These findings coincide with Seginer’s (2008) model in which a sense of hope mediates the relationship between threat and challenge appraisals and future expectations. As indicated by Seginer, these threat and challenge appraisals may stem from political violence or dangers in one’s community. The present model expanded Seginer’s hypotheses by examining positive community-oriented resources and a general sense of hope and future expectations. Indeed, recognizing one’s resources in general as being sufficient to meet challenges may lead to optimistic views of the future. When individuals have an overall sense that goals can be met (Snyder et al., 1997), they may anticipate being able to overcome any challenges that arise in order to attain a bright and desirable future. Hope provides self-regulatory functions, such that it can motivate and guide behavior (Schmid & Lopez, 2011).

Limitations should be noted. First, due to the cross-sectional nature of the study our ability to determine causality is limited. Longitudinal studies should be conducted to examine these relationships across time. Additionally, the sample included 7th- grade students from a single middle school. Therefore, our findings may not generalize to all youth. Though our sample provides unique insight into this sample of youth, future research should investigate these relationships in other samples of youth. Furthermore, other community and intraindividual factors may be important. For example, the present study focused on self-reported perceptions of community-oriented resources; future research should examine objective community-level factors such as the availability of youth-serving organizations and neighborhood socioeconomic status. Peers can also play a role in developing purpose in life. When adolescents are surrounded by peers who are pursuing similar interests, activities are more likely to be engaging and fun. Therefore, youth are more likely to build close relationships with these peers and, consequently, are more likely to be committed to their shared interests (Bronk, 2014). Additionally, future research should explore the content of purpose and how this relates to hope. According to Snyder (1995), hope is particularly fostered when goals are concrete and attainable. Therefore, ambiguous or unattainable overarching life goals may not predict hope as well as when they are firmly articulated.

Notwithstanding these limitations, the findings add to our understanding of promotive factors that are associated with positive future expectations among adolescents. Interventions that foster a sense of neighborhood collective efficacy and enable youth to become involved in community work may be beneficial. Furthermore, interventions that focus on self-concept and future expectations specifically have shown beneficial effects (Johnson, Jones, & Cheng, 2015; Oyserman, Terry, & Bybee, 2002). Notably, motivational interventions that engage youth in discussing future plans and goals have been linked to increased self-efficacy and reductions in risk behaviors (Johnson et al., 2015). Incorporating additional elements, such as helping adolescents foster a sense of hope and identify a purpose in life by exploring what is meaningful to them and establishing concrete overarching life goals, may further promote adolescent well-being and positive development. Through these efforts, researchers and interventionists may direct youth to a brighter future.

Acknowledgments

S. Stoddard is supported by a Mentored Scientist Career Development Award (1K01 DA 034765) from the National Institute on Drug Abuse. J. Pierce was supported by an internship award from The University of Michigan Injury Center (CDC F031412).

Contributor Information

Sarah A. Stoddard, Email: sastodda@umich.edu.

Jennifer Pierce, Email: ed1051@wayne.edu.

References

- Adelabu DH. Future time perspective, hope, and ethnic identity among African American adolescents. Urban Education. 2008;43:347–360. [Google Scholar]

- Adler RP, Goggin J. What do we mean by “civic engagement? Journal of Transformative Education. 2005;3:236–253. [Google Scholar]

- Arnett JJ. High hopes in a grim world: Emerging adults’ views of their futures and “Generation X. Youth and Society. 2000;31:267–286. [Google Scholar]

- Aronowitz T. The role of “envisioning the future” in the development of resilience among at-risk youth. Public Health Nursing. 2000;22:200–208. doi: 10.1111/j.0737-1209.2005.220303.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benson PL. All kids are our kids. 2. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Bronk K. Purpose in life: A critical component of optimal youth development. New York: Springer Dordrecht; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Bronk KC, Hill PL, Lapsley DK, Talib TL, Finch H. Purpose, hope, and life satisfaction in three age groups. The Journal of Positive Psychology. 2009;4:500–510. [Google Scholar]

- Burrow AL, Hill PL. Purpose as a form of identity capital for positive youth adjustment. Developmental Psychology. 2011;47:1196–1206. doi: 10.1037/a0023818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins CR, Neal JW, Neal ZP. Transforming individual civic engagement into community collective efficacy: The role of bonding social capital. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2014;54:328–336. doi: 10.1007/s10464-014-9675-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damon W. What is positive youth development? Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. 2004;591:13–24. [Google Scholar]

- Dubow EF, Arnett M, Smith K, Ippolito MF. Predictors of future expectations of inner-city children: A 9-month prospective study. Journal of Early Adolescence. 2001;21:5–28. [Google Scholar]

- Erikson EH. Identity: Youth and crisis. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, Inc; 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Esteves M, Scoloveno RL, Mahat G, Yarcheski A, Scoloveno MA. An integrative review of adolescent hope. Journal of Pediatric Nursing. 2013;28:105–113. doi: 10.1016/j.pedn.2012.03.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans SD. Youth sense of community: Voice and power in community contexts. Journal of Community Psychology. 2007;35:693–709. [Google Scholar]

- George LS, Park CL. Are meaning and purpose distinct? An examination of correlates and predictors. The Journal of Positive Psychology. 2013;8:365–375. [Google Scholar]

- Hill PL, Burrow AL, Bronk KC. Persevering with positivity and purpose: An examination of purpose commitment and positive affect as predictors of grit. Journal of Happiness Studies in press. [Google Scholar]

- Hill PL, Burrow AL, Sumner R. Addressing important questions in the field of adolescent purpose. Child Development Perspective. 2013;7:232–236. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson SL, Jones V, Cheng TL. Promoting “Healthy Futures” to reduce risk behaviors in urban youth: A randomized controlled trial. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2015;56:36–45. doi: 10.1007/s10464-015-9734-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kashdan TB, McKnight PE. Origins of purpose in life: Refining our understanding of a life well lived. Psychological Topics. 2009;18:303–316. [Google Scholar]

- Kerpelman JL, Eryigit S, Stephens CJ. African American adolescents’ future education orientation: Associations with self-efficacy, ethnic identity, and perceived parental support. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2008;37:997–1008. [Google Scholar]

- Kirk CM, Lewis RK, Lee FA, Stowell D. The power of aspirations and expectations: The connection between educational goals and risk behaviors among African American adolescents. Journal of Prevention & Intervention in the Community. 2011;39:320–332. doi: 10.1080/10852352.2011.606406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leventhal T, Brooks-Gunn J. The neighborhoods they live in: The effects of neighborhood residence on child and adolescent outcomes. Psychological Bulletin. 2000;126:309–337. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.126.2.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorion RP, Saltzman W. Children’s exposure to community violence: Following a path from concern to research to action. Psychiatry. 1993;56:55–65. doi: 10.1080/00332747.1993.11024621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch WF. Images of hope: Imagination as healer of the hopeless. Baltimore: Helica Press; 1965. [Google Scholar]

- McDade TW, Chyu L, Duncan GJ, Hoyt LT, Doane LD, Adam EK. Adolescents’ expectations for the future predict health behaviors in early adulthood. Social Science & Medicine. 2011;73:391–398. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGee RF. Hope: A factor influencing crisis resolution. Advances in Nursing Science. 1984;6:34–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKnight PE, Kashdan TB. Purpose in life as a system that creates and sustains health and well-being: An integrative, testable theory. Review of General Psychology. 2009;13:242–251. [Google Scholar]

- Mello ZR, Swanson DP. Gender differences in African American adolescents’ personal, educational, and occupational expectations and perceptions of neighborhood quality. Journal of Black Psychology. 2007;33:150–168. [Google Scholar]

- Michigan Department of Education. MI school data: Student counts. 2014 Retrieved from https://www.mischooldata.org/DistrictSchoolProfiles/StudentInformation/StudentCounts/StudentCount.aspx.

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus User’s Guide. 7. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Nurmi J. How do adolescents see their future? A review of the development of future orientation and planning. Developmental Review. 1991;11:1–59. [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien DT, Kauffman RA. Broken windows and low adolescent prosociality: Not cause and consequence, but co-symptoms of low collective efficacy. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2013;51:359–369. doi: 10.1007/s10464-012-9555-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oyserman D, Terry K, Bybee D. A possible selves intervention to enhance school involvement. Journal of Adolescence. 2002;25:313–326. doi: 10.1006/jado.2002.0474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padelford BL. Relationship between drug involvement and purpose in life. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 1974;30:303–305. doi: 10.1002/1097-4679(197407)30:3<303::aid-jclp2270300323>3.0.co;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryff CD. Happiness is everything, or is it? Explorations on the meaning of psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1989;57:1069–1081. [Google Scholar]

- Sampson RJ, Raudenbush SW. Systematic social observation of public spaces: A new look at disorder in urban neighborhoods. American Journal of Sociology. 1999;105:603–651. [Google Scholar]

- Sampson RJ, Raudenbush SW, Earls F. Neighborhoods and violent crime: A multilevel study of collective efficacy. Science. 1997;277:918–924. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5328.918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scales PC, Leffert N. Developmental assets: A synthesis of the scientific research on adolescent development. Minneapolis, MN: Search Institute; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Scheier MF, Carver CS. Effects of optimism on psychological and physical well-being: Theoretical overview and empirical update. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 1992;16:201–228. [Google Scholar]

- Schmid KL, Lopez SJ. Positive pathways to adulthood: The role of hope in adolescents’ constructions of their futures. Advances in Child Development and Behavior. 2011;41:69–88. doi: 10.1016/b978-0-12-386492-5.00004-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmid KL, Phelps E, Lerner RM. Constructing positive futures: Modeling the relationship between adolescents’ hopeful future expectations and intentional self regulation in predicting positive youth development. Journal of Adolescence. 2011;34:1127–1135. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2011.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz CE, Keyl PM, Marcum JP, Bode R. Helping others shows differential benefits on health and well-being for male and female teens. Journal of Happiness Studies. 2009;10:431–448. [Google Scholar]

- Seginer R. Future orientation in times of threat and challenge: How resilient adolescents construct their future. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 2008;32:272–282. [Google Scholar]

- Shamah D. Supporting a strong sense of purpose: Lessons from a rural community. New Directions in Youth Development. 2011;132:45–58. doi: 10.1002/yd.427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shorey HS, Little TD, Snyder CR, Kluck B, Robitschek C. Hope and personal growth initiative: A comparison of positive, future-oriented constructs. Personality and Individual Differences. 2007;43:1917–1926. [Google Scholar]

- Sipsma HL, Ickovics JR, Lin H, Kershaw TS. Future expectations among adolescents: A latent class analysis. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2012;50:169–181. doi: 10.1007/s10464-011-9487-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sipsma HL, Ickovics JR, Lin H, Kershaw TS. The impact of future expectations on adolescent sexual risk behavior. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2015;44:170–183. doi: 10.1007/s10964-013-0082-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder CR. Conceptualizing, measuring, and nurturing hope. Journal of Counseling & Development. 1995;73:355–360. [Google Scholar]

- Snyder CR. Hope theory: Rainbows in the mind. Psychological Inquiry. 2002;13:249–275. [Google Scholar]

- Snyder CR, Hoza B, Pelham WE, Rapoff M, Ware L, Danovsky M, Highberger L, Rubinstein H, Stahl KJ. The development and validation of the Children’s Hope Scale. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 1997;22:399–421. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/22.3.399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoddard SA, Zimmerman MA, Bauermeister JA. Thinking about the future as a way to succeed in the present: A longitudinal study of future orientation and violent behaviors among African American youth. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2011;48:238–246. doi: 10.1007/s10464-010-9383-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stotland E. The psychology of hope. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Sun RCF, Shek DTL. Beliefs in the future as a positive youth development construct: A conceptual review. The Scientific World Journal, 2012. 2012 doi: 10.1100/2012/527038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valle MF, Huebner ES, Suldo SM. An analysis of hope as a psychological strength. Journal of School Psychology. 2006;44:393–406. [Google Scholar]

- Wyman PA, Cowen EL, Work WC, Kerley JH. The role of children’s future expectations in self-system functioning and adjustment to life stress: A prospective study of urban at-risk children. Development and Psychopathology. 1993;5:649–661. [Google Scholar]

- Yarcheski A, Scoloveno MA, Mahon NE. Social support and well-being in adolescents: The mediating role of hopefulness. Nursing Research. 1994;43:288–292. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Youniss J, Yates M. Community service and social responsibility in youth. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]