Abstract

Purpose

To study the effects of magnetization transfer (MT) on multi-component T2 parameters obtained using mcDESPOT in macromolecule-rich tissues and to propose a new method called mcRISE to correct MT-induced biases.

Methods

The two-pool mcDESPOT model was modified by the addition of an exchanging macromolecule proton pool to model the MT effect in cartilage. An mcRISE acquisition scheme was developed to provide sensitivity to all pools. An incremental fitting was applied to estimate MT and relaxometry parameters with minimized coupling. The interaction between MT and relaxometry parameters, efficacy of MT correction, and feasibility of mcRISE in-vivo were investigated in simulations and in healthy volunteers.

Results

The MT effect caused significant errors in multi-component T1/T2 values and in fast-relaxing water fraction fF, which is consistent with previous experimental observations. fF increased significantly with macromolecule content if MT was ignored. mcRISE resulted in a multi-fold reduction of MT biases and yielded decoupled multi-component T1/T2 relaxometry and quantitative MT parameters.

Conclusion

mcRISE is an efficient approach for correcting MT biases in multi-component relaxometry based on steady-state sequences. Improved specificity of mcRISE may help to elucidate the sources of the previously described high sensitivity of non-corrected mcDESPOT parameters to disease-related changes in cartilage and brain.

Keywords: multi-component relaxometry, magnetization transfer, cartilage imaging, steady-state sequences

INTRODUCTION

Quantitative mapping of transverse (T2) relaxation times may serve as an imaging marker more sensitive to disease-related tissue changes than conventional magnetic resonance (MR) imaging (1). One emerging application of T2 relaxometry is the characterization of the extracellular matrix of articular cartilage, which is a complex structure composed primarily of water and smaller concentrations of macromolecules including type-II collagen and proteoglycan (1,2). T2 has been shown to be sensitive to changes in the composition and micro-structure of the cartilage extracellular matrix during various stages of cartilage degeneration (3,4). However, single-component T2 mapping (5-7) effectively averages signal from the multiple water compartments associated with the different constituents of the cartilage extracellular matrix into a single composite measurement. Hence, multi-component T2 relaxometry using multiple spin-echo imaging has recently been proposed to improve the specificity of relaxometric measurements by exploring differences in T2 characteristics between the different water compartments (8-12). Several studies have specifically assessed different water compartments within cartilage using nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy (8-11). In particular, two primary water components (T2~25 ms and T2~96 ms) were found to be associated with water bound to proteoglycan (WPG) and bulk water (WBW) respectively (8,9).

Multi-component T2 analysis using standard multiple spin-echo images is challenging in in-vivo cartilage applications due to long acquisition times. Therefore, its application has been primarily limited to ex-vivo cartilage samples (8,10,11). Recently, the multi-component Driven Equilibrium Single Pulse Observation (mcDESPOT) technique has demonstrated the feasibility of using fast Spoiled Gradient Echo (SPGR) and balanced Steady-State Free Precession (bSSFP) sequences (13) for three-dimensional multi-component T2 relaxometry in-vivo, particularly in several neuroimaging applications (14-17). More recently, this technique has been used for in-vivo whole knee joint imaging to assess the fast and slowly relaxing water components of cartilage which are often assigned to water bound to proteoglycan (WPG) and bulk water (WBW) respectively (18). In another study, the fraction of the fast relaxing water component has been shown to have greater diagnostic performance than single-component T2 for distinguishing between normal and degenerative cartilage in human subjects (19).

One limitation of many relaxometric techniques based on steady-state imaging is the lack of consideration of magnetization transfer (MT) exchange between the water protons and macromolecular protons. Traditionally, this exchange pathway is exploited in off-resonance MT saturation experiments to create MT contrast, which in the case of cartilage is primarily determined by a collagen component of the cartilage matrix (20-22). However, it was recently recognized that this exchange pathway may strongly affect the signals of both SPGR and bSSFP signals even in the absence of off-resonance MT saturation pulse. This signal attenuation may affect the single-component T1/T2 MR relaxation rates estimated using standard relaxometric approaches based on the steady-state pulse sequences (23-25). Ou et al. (23) demonstrated that these MT-induced signal attenuations (referred to as on-resonance MT effect) in variable flip angle (VFA) SPGR T1 mapping can lead to >10% errors in T1 values for white matter. Mossahebi et al. (24) found that the T1 estimation bias is directly dependent of the macromolecular proton content and largely independent of pulse sequence parameters. Bieri et al. (25) reported significant reduction of bSSFP signal in brain images due to the presence of strong on-resonance MT effect in bSSFP sequences. Gloor et al. (26,27) explored these effects to develop a quantitative MT imaging (qMTI) technique to assess parameters of two-pool MT model. The unaccounted on-resonance MT effect could be also a possible source of estimation uncertainty of multi-component relaxometry in steady state. A recent study by Zhang et al. (28) compared T2 values from spin-echo experiment and mcDESPOT in brain white matter, where short T2 component is associated with the water trapped between layers of myelin, the primary source of macromolecular content in neural tissues (29). The study reported that mcDESPOT considerably overestimates relative fraction of the short T2 component and underestimates the T2 of brain white matter. The on-resonance MT may also have a significant effect on cartilage multi-component relaxometry in steady-state due to a strong magnetization transfer (MT) effect in cartilage tissue (20,30,31).

The goal of this study is to evaluate effects of MT on multi-component T1/T2 parameters of mcDESPOT in macromolecule-rich tissues such as cartilage, and to propose a new method called multi-component Relaxation Imaging using Steady-state signal Evolution (mcRISE) for MT-corrected estimation of the parameters. Following the cartilage modeling results of previous studies (11), we aim to achieve such correction by introducing an additional macromolecular proton pool in exchange with the two original mcDESPOT water proton pools and expanding the set of mcDESPOT measurements by MT-sensitive bSSFP acquisitions. In the following, we describe theoretical background, modeling equations, and mcRISE’s model approximations which are further validated in a series of simulations and in initial in-vivo studies.

THEORY

Mathematical Models and Corresponding Bloch Equations

We first consider a composite spin system including two exchanging water pools (fast (F) and slowly (S) relaxing water pools) described in the mcDESPOT method (13) (Fig. 1a). Based on the Bloch-McConnell equation (32), the spin evolution of transverse (x, y) and longitudinal (z) magnetization components of each water pool can be expressed as follows:

| [1] |

| [2] |

| [3] |

| [4] |

| [5] |

| [6] |

where kSF, kFS are rates of (diffusion-driven) magnetization exchange between S and F pools and vice versa, respectively, and Δω is the off-resonance frequency caused by B0 field inhomogeneity. R1=1/T1 and R2=1/T2 are longitudinal and transverse relaxation rates, respectively.

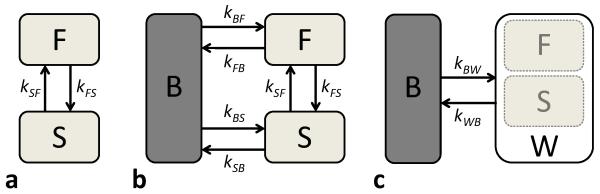

Figure 1.

In mcRISE, the basic mcDESPOT model consisting of slow (S) and fast (F) relaxing water pools (a) is enhanced by an additional macromolecular proton pool (B) (b). The fitting pipeline uses a 2-pool approximation of mcRISE model (c) to determine parameters associated with the macromolecular proton pool.

To consider the effect of MT exchange with macromolecules on the measurable water signal, we introduce the third macromolecular proton pool (B) into the system (Fig. 1b). In this work, we consider a general case where MT exchange pathways exist between macromolecular protons and both F and S water components which correspond to previously NMR-validated models of magnetization exchange in cartilage (11). These modifications to the original mcDESPOT model (Fig. 1a) lead to two additional terms in both Eq. [3] and Eq. [6] which describe the magnetization exchange with forward (backward) rates kFB,kSB (kBF,kBS ):

| [7] |

| [8] |

The longitudinal magnetization of the macromolecular proton pool can be described as

| [9] |

The above equations can be simplified into a compact matrix form as

| [10] |

Here, all relaxation and exchange terms are included into a matrix A defined as follows:

| [11] |

| [12] |

| [13] |

Vector contains components of the transverse and longitudinal magnetizations of each pool, and vector . Here, “T” denotes the transpose operation and M0 is the total equilibrium magnetization, fF and fS are fractional magnetizations for fast and slow water proton pools normalized by total water magnetization to preserve mcDESPOT definitions. f is macromolecular proton fraction (MPF) defined in respect to total magnetization (water plus macromolecule protons) to preserve qMTI definitions. At chemical equilibrium, the fractional magnetizations and exchange rates may be related as kFBfF = kBFf, kSBfS = kBSf and kFSfF = kSFfS.

Multi-Component bSSFP Signal Solution for Proposed Three-pool Model

For the bSSFP signal, an analytical solution of Eq. [10] can be derived using the steady-state condition approach (33) which yields the steady-state magnetization:

| [14] |

where , , ρbSSFP is the total equilibrium magnetization weighted by T2 decay and instrumental scaling terms (34), I is the 7×7 identity matrix, TR is the sequence repetition time, and matrix describes a rotation of water pool magnetizations around x-axis and macromolecular pool saturation due to RF excitation with the prescribed flip angle α. can be expanded as follows:

Here, the average macromolecular proton pool saturation rate at off-resonance frequency Ω is given as a function of time-dependent transmitting field and RF pulse duration TRF (35):

| [15] |

We use a standard Super-Lorentzian line shape G(Ω) (36) for modeling the macromolecular proton pool MT saturation given by:

| [16] |

Similar to method of Gloor et. al. (27), we provide sensitivity of a steady-state bSSFP signals to MT exchange by varying TRF which causes different on-resonance MT saturations which is referred to in this paper as the variable RF pulse width (VRF) approach. Finally, the observed bSSFP signal is calculated as the magnitude of the complex summation of the transverse magnetizations of water components F and S:

| [17] |

Multi-Component SPGR Signal Solution for Proposed Three-pool Model

SPGR signal can be derived in a similar fashion. Under assumption of perfect spoiling (destruction of transverse magnetization) at the end of each TR, an analytical solution to the Eq. [10] for the steady-state signal at SPGR sequence can be expressed in the matrix form yielding the steady-state magnetization:

| [18] |

where , I is now the 3×3 identity matrix. RF pulse rotation matrix and vector CSPGR are expressed as follows:

where ρSPGR is the total equilibrium magnetization weighted by decay and instrumental scaling terms. The observed SPGR signal can be calculated as follows:

| [19] |

METHODS

mcRISE Model Fitting

We found that simultaneous fit for all parameters of the mcRISE model is non-feasible due to the size of optimization search space (37), which is expanded by more additional parameters compared to mcDESPOT’s set of parameters. Hence, to obtain MT-corrected estimates of water pool parameters, we developed an incremental fitting approach based on several simplifications. Estimates of the MT-related model parameters are first obtained using a two-pool MT model (Fig. 1c), which is a standard approximation of complex tissue models (27). Similar to other qMT techniques (27,38,39), T1,B was set to 1 s (a common assumption of most qMT methods), and T2,B was fixed to 8 μs (mean value in articular cartilage tissues) (31). The estimated parameters of the two-pool model f and k are then used in the full mcRISE model fit as fixed estimates of the macromolecular proton fraction and exchange rates (kFB,kSB), respectively. The effect of these simplifications will be investigated in separate simulations later in the study. ρbSSFP and ρSPGR were fitted as independent parameters to absorb effects of unequal echo times in bSSFP and SPGR sequences.

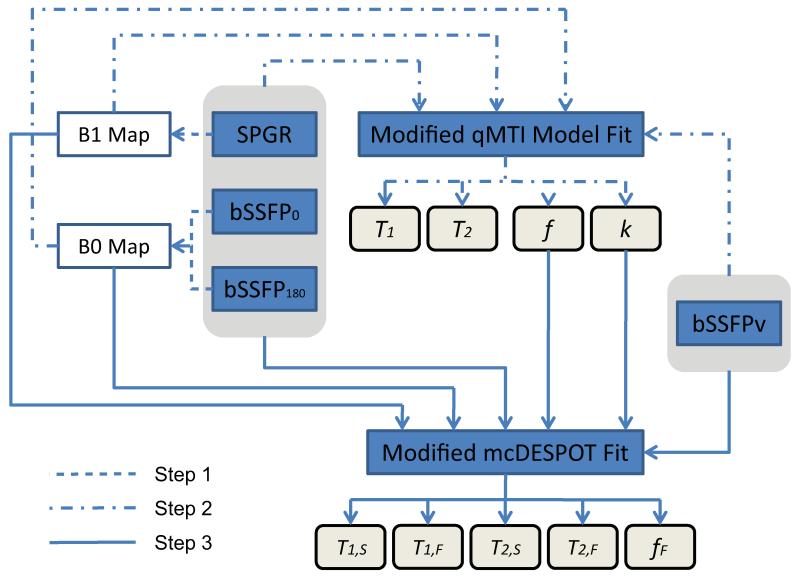

The entire model fitting pipeline is shown in Fig. 2. The input images consist of datasets with varying flip angle (VFA) SPGR, bSSFP with no RF phase-cycling (bSSFP0) and with 180° RF phase-cycling (bSSFP180) (for characterizing T1 and T2 relaxation modulation similar to mcDESPOT experiment design), and varying RF pulse width (VRF) bSSFP with 180° RF phase-cycling (bSSFPv) (for characterizing MT modulation similar to on-resonance qMTI (27)). Additionally, inversion recovery SPGR data are acquired for estimating B1 non-uniformity (40). The processing pipeline can be divided into three steps:

Figure 2.

Flowchart of mcRISE processing.

Step 1: B0/B1 Calibration

To account for main magnetic and RF transmit field inhomogeneities, the estimates of B0 and B1 fields are obtained using DESPOT-FM (41) and DESPOT-HIFI (40) respectively. To provide B0/B1-insensitive parameter evaluation, the estimated B0 and B1 values are used in the subsequent fits (Step 2 and Step 3) to adjust excitation flip angles (in SPGR and bSSFP signal models) and B0-dependent entries of A1 matrix (in bSSFP signal model) respectively.

Step 2: Two-pool MT Model Fit

In this stage, all steady state data (SPGR, bSSFP180, bSSFP0 and bSSFPv) are fitted simultaneously to a two-pool MT model. The two-pool MT modeling equations are obtained after corresponding simplification of the three-pool model equations (Eqs. [14],[18]). Namely, the slow relaxing pool S is substituted with cumulative water pool W, and all entries and corresponding matrix row/columns associated with the fast relaxing pool F are eliminated. All processing is performed using B0/B1 corrections as described in Step 1. This stage also yields the MT-corrected single-component T1 and T2 relaxation times which will be treated as nuisance parameters for the purposes of this paper.

Step 3: Multi-Component T1/T2 Fit

The final simultaneous fit of SPGR, bSSFP180, bSSFP0 and bSSFPv signals (Eqs. [14],[18]) is performed using B1/B0 values estimated in Step 1, and f and k values estimated in Step 2.

Numerical Simulations

Numerical simulations were performed to compare accuracy and stability of multi-component T2 parameter estimation using the mcDESPOT and mcRISE methods. Theoretical SPGR, bSSFP180, bSSFP0 and bSSFPv signal data were generated based on MT-modulated steady-state equations as described in the Theory section. All data was fitted with the mcRISE method, while a subset of data (SPGR, bSSFP180, bSSFP0) was fitted with the mcDESPOT method. A total of 50,000 instances of noise were added to the signal in Monte-Carlo simulations to measure the accuracy and precision of the parameter estimation for T1,F, T1,S, T2,F, T2,S, fF, f and k. The performance measure included the percentage error, which was defined as the difference between the estimated mean and true parameter value divided by the true parameter value. The same simulation was repeated with different levels of added Gaussian noise at signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) = 50, 100 and 200 where the SNR was defined in respect to the maximum signal.

The set of model parameters used in the numerical simulations was chosen to mimic parameters of articular cartilage previously published in the literature (9,18,31). According to previously identified associations of the different water components of cartilage (8,9), we assigned the fast relaxing water pool F to proteoglycan-bound water (WPG) and the slowly relaxing water pool S to free bulk water (WBW). The main parameters of interest in context of cartilage imaging include T2,S, T2,F, and fF (18). Accordingly, parameters of the two WPG and WBW water pools were chosen as follows: T1,S = 1800ms, T1,F = 400ms, T2,S = 80ms, T2,F = 20ms, fF = 0.25, and kfs = 9 s−1. The parameters associated with the macromolecular proton pool were chosen as follows: T1,B = 1s, T2,B = 8μs, f = 0.2, and k = kFB = kSB = 5 s−1. The SPGR, bSSFP0, bSSFP180 and bSSFPv signals were generated using the experimental design of the in-vivo protocol described in the next subsection.

Additional numerical simulations were performed to investigate the effect of two-stage model fit and modeling simplifications on the estimation accuracy and to compare it with accuracy of mcDESPOT fit for a range of exchange rates kFB and kSB (from 1 to 10 s−1), f (from 5% to 25%) and k (here, assume k = kFB = kSB from 1 to 10s−1), respectively. For each main parameter of interest (T1,F, T1,S, T2,F, T2,S, fF, f), the percentage error was calculated for 20,000 noise realizations (SNR = 100) for both the mcDESPOT and mcRISE methods.

In-vivo Human Knee Study

An in-vivo knee study was used to test the feasibility of the mcRISE method for assessing multi-component T2 relaxation characteristics of the articular cartilage of the human knee joint in reasonable scan times. The in-vivo study was performed with approval from our Institutional Review Board and in compliance with Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act regulations. All subjects were informed with written consent prior to their participation in the study. An MR examination of the knee was performed on three young asymptomatic volunteers (three males with the ages of 28 years, 30 years and 33 years) using a 3.0T scanner (Discovery MR750, GE Healthcare, Waukesha, WI, USA) and 8-channel knee coil (InVivo, Orlando, FL, USA). All scans were performed in the sagittal plane with complete anatomic coverage of the knee joint. The common acquisition parameters for all scans included a 16 cm FOV, 256×256 matrix size, 3mm slice thickness, 32 acquired slices, and readout bandwidth = ± 83.33 KHz. The other parameters of the mcRISE pulse sequences included: 1) SPGR: α = (3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 9, 13, 18)°, TRF/TR/TE = 0.8/4.8/2.2 ms, scan time 4.5 min; 2) bSSFP0/bSSFP180: α = (2, 5, 10, 15, 20, 30, 40, 50)°, TRF/TR/TE = 0.8/5.6/2.8 ms, scan time 11 min; 3) bSSFPv: α = 35°, TRF/TR/TE = (0.2/5.6/2.8, 0.3/5.6/2.8, 0.4/5.6/2.8, 0.6/5.6/2.8, 0.8/5.6/2.8, 1.2/5.8/2.9, 1.6/6.1/3.1, 2/6.5/3.2) ms, scan time 8 min. For DESPOT-HIFI B1 mapping, an inversion recovery SPGR scan was acquired with TR/TE=4.8/2.2ms, TI=450ms, α =5°, readout bandwidth = ± 83.33 KHz, and 1.5 min scan time. The total scan time for the mcRISE protocol was 25 minutes.

Multi-Component Relaxation Time Analysis for In-vivo Data

FLIRT image registration software (Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging of the Brain Analysis Group, Oxford University, UK) was used for correcting subject motion during each MR scan. All image processing and voxel-by-voxel model fitting were performed using an in-house program developed in Matlab (Matlab 2013a, MathWorks, Natick, MA, USA) and executed under a desktop computer hosting an Intel Xeon W3520 CPU (Intel, Santa Clara, CA, USA). The effect of MT correction on both single and multi-component T2 relaxation mapping was studied. Single-component T1/T2 relaxation time maps of the articular cartilage were obtained from both the standard DESPOT-HIFI (40), DESPOT-FM (41) and proposed mcRISE models. Multi-component T1/T2 maps and fast component fraction fF of the articular cartilage were obtained from the standard mcDESPOT (13) and mcRISE models. f and k maps were obtained from the mcRISE model only. Following methodology of Ref. (27), we calculated the on-resonance saturation using an extrapolated line shape value at zero frequency (G(0) = 1.4e−5 s−1 at T2,B = 8 μs) to avoid Super-Lorentzian singularity at this frequency. In the mcRISE model fitting process, a standard Nelder-Meed Simplex method (‘fminsearch’ function in Matlab) was applied for Step 1 and 2 of the fitting pipeline. In Step 3, a Stochastic Contraction (SC) method adapted from the original mcDESPOT method was utilized for estimating the multi-component T1/T2 relaxation parameters (13).

To demonstrate the quality of curve fitting for both mcRISE and mcDESPOT, the goodness of fit measures were compared for averaged signals from several small homogenous region-of-interests (ROIs). The ROIs were chosen from a sagittal slice in the central portion of patella, trochlea and lateral tibia plateau to avoid partial volume effect with synovial fluid and subchondral bone in the superficial and deep cartilage layers, respectively. Model preference was quantified using the Bayesian information criterion (BIC) (42). This criterion allows identification of the optimal fitted model with consideration of a potential overfit effect due to the increased number of free parameters in the model. For pixel-wise analysis, larger ROIs were placed on the same three cartilage subsections for all three subjects. The mean value and standard deviation of the multi-component relaxation parameters of all the voxels within the ROI were recorded for each subject and used for comparison analysis between the mcDESPOT and mcRISE methods.

RESULTS

Numerical Simulations

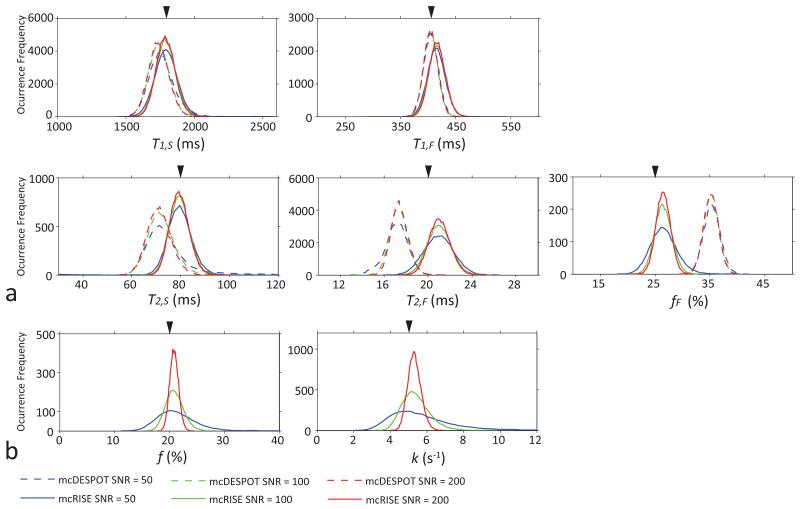

Figure 3 shows simulation results comparing the accuracy and robustness of mcRISE and mcDESPOT fits in the presence of macromolecule-rich tissues. The difference between the mean value of the estimated parameters and the ground truth values reveals deviation of the mcDESPOT-estimated parameters from ground truth at all SNR levels (Fig. 3a). T2,F, T2,S, fF are most and T1,F, T1,S are least affected by the lack of MT exchange modeling in the mcDESPOT fit. In these simulations, fF and T1,F were increased by 41.2% and 1.5% respectively, and T2,F, T2,S and T1,S were decreased by 14.5%, 11% and 3.4% respectively at the maximum bias. It can be also seen that mcRISE estimates also resulted in non-zero biases due to simplifications in the model fit. The biases in mcRISE estimates were at 6%, 3.7%, 0.5%, 5% and 0.5% levels for fF, T1,F, T1,S, T2,F and T2,S respectively. The MPF f and exchange rate k estimated by mcRISE show similar level of bias errors (maximum 5% and 6% errors for f and k respectively) (Fig. 3b). These errors arise because the standard two-pool MT model used on the first stage of the mcRISE fit is a simplification of a more complex three-pool model used to describe the steady-state signal in cartilage (Fig. 1 and 2).

Figure 3.

Comparison of mcDESPOT and mcRISE performances for the MT-enhanced signal model in Monte-Carlo simulations. The arrowheads identify true values of each parameters used in the simulations. Note improved accuracy of estimation of mcRISE.

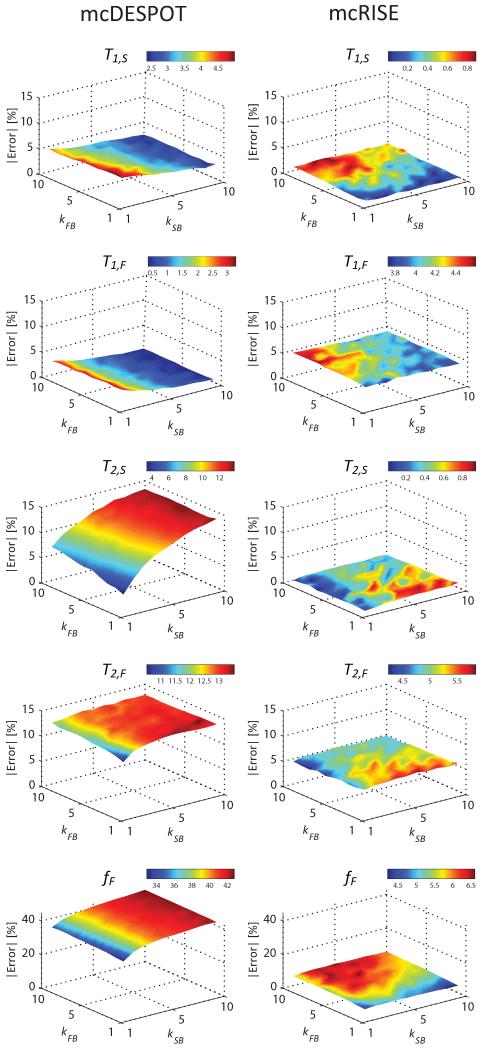

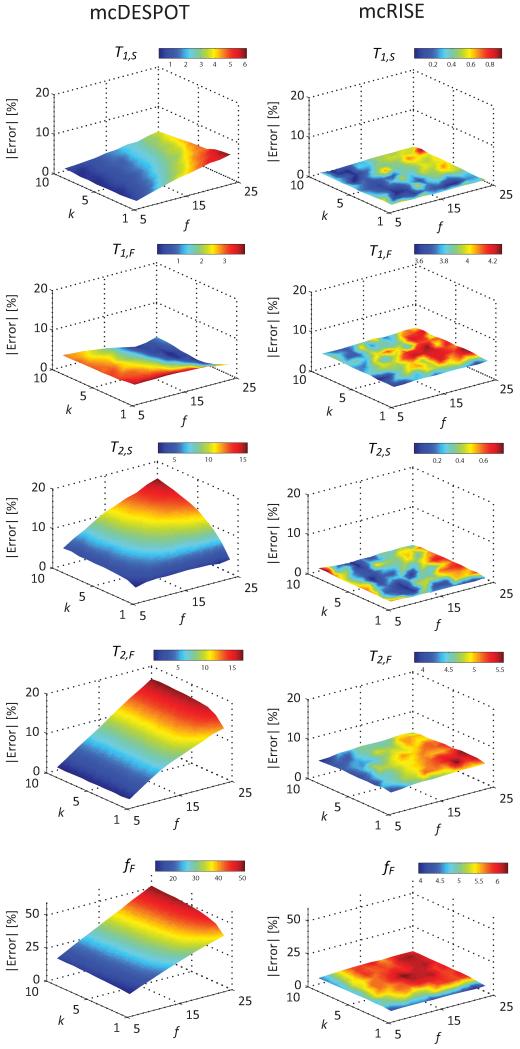

Figure 4 further studies the effect of model simplifications adopted in mcDESPOT and mcRISE on the accuracy of multi-component T1/T2 parameter estimates in the range of MT exchange rates. mcDESPOT estimates are significantly biased compared to the ground truth values for all combinations of MT exchange rates, with fF being affected the most (maximum errors of 5.0%, 3.3%, 13.7%, 13.5% and 42.7% for T1,S, T1,F, T2,S, T2,F and fF respectively). The sequential fit of mcRISE method also results in non-zero estimation bias at all MT exchange rates with macromolecular proton pool, but at much smaller or comparable levels (maximum errors of 0.9%, 4.6%, 0.9%, 5.8% and 6.6% for T1,S, T1,F, T2,S, T2,F and fF respectively). Importantly, the levels of mcRISE bias are relatively uniform in all range of the MT exchange rates (standard deviation of errors of 0.2%, 0.2%, 0.2%, 0.3% and 0.6% for T1,S, T1,F, T2,S, T2,F and fF respectively) which indicates that the two-pool MT approximation used on the first stage of mcRISE fit produces consistent estimation for various combinations of the approximated exchange rates kFB and kSB.

Figure 4.

Effect of mcRISE model fit simplifications on estimation accuracy of T1/T2 parameters, and its comparison with mcDESPOT accuracy for ranges of the exchange rates.

Figure 5 shows the numerical simulation results investigating the sensitivity of multi-component T1/T2 parameter estimation to qMT parameters f and k (where k = kFB = kSB). Underestimation of T1,S, T2,S and T2,F and overestimation of fF in the mcDESPOT method increases rapidly with the increase of the macromolecular fraction f and changes more slowly with k (maximum errors of 6.1%, 15.7%, 17.0% and 51.3% for T2,S, T2,F and fF respectively). Remarkably, fF grows in a linear manner with f indicating that if MT effects are ignored, this parameter may represent not only the ratio of water components but also the tissue macromolecular content. Other parameters including T1,F, T1,S, T2,F and T2,S are also strongly affected by f, while T2,S is strongly affected by k. At the same time, the mcRISE method provides multi-component T1/T2 parameters with substantially less or comparable absolute percentage errors over the simulation ranges (maximum errors of 0.9%, 4.2%, 0.8%, 5.6% and 6.3% for T1,S, T1,F, T2,S, T2,F and fF respectively). Importantly, the level of residual bias is uniform in the ranges of f and k (standard deviation of errors of 0.2%, 0.2%, 0.2%, 0.4% and 0.6% for T1,S, T1,F, T2,S, T2,F and fF respectively) indicating the loss of correlation between multi-component T1/T2 and MT parameters in mcRISE in which the MT effect is modeled explicitly.

Figure 5.

Effect of varying f and k in mcRISE model fit on estimation accuracy of T1/T2 parameters, and its comparison with mcDESPOT accuracy.

In-Vivo Knee Study

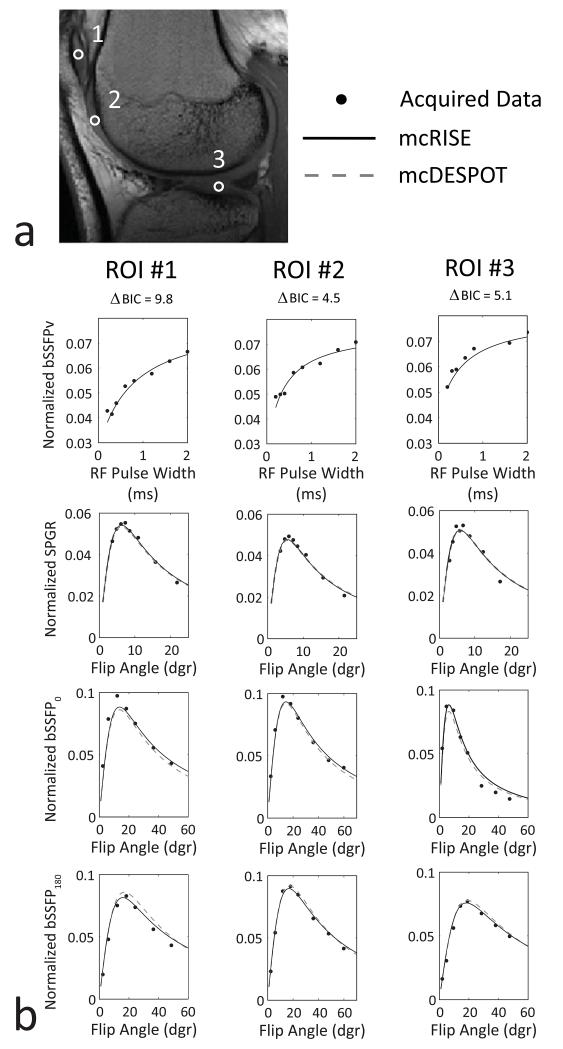

Figure 6 demonstrates the fitting results for the in-vivo knee study. The three ROIs within the patella (first column), trochlea (second column) and lateral tibia plateau (third column) are shown as white circles on the image of a 30 years old male volunteer (Fig. 6a). The increasing bSSFPv signal in the first row plot in Fig. 6b corresponds to the reduction of MT saturation for wider RF pulses. As mcDESPOT does not directly model MT, bSSFPv subset of the data was fit only by the mcRISE model, while the rest of the SPGR/bSSFP data was used by both the mcDESPOT and mcRISE models. The fitted curves were plotted to demonstrate the fitting quality for both mcDESPOT and mcRISE. In all cartilage subregions, both the mcDESPOT and mcRISE models provide good agreement with their individual subsets of data (SPGR/bSSFP for mcDESPOT and SPGR/bSSFP/bSSFPv for mcRISE). When compared with the mcDESPOT model, the mcRISE model incorporating MT effect provides better data fitting quality for the in-vivo cartilage images with improved (i.e. lower) BIC values.

Figure 6.

Comparison of mcDESPOT and mcRISE data fits in cartilage. a: ROI placement (ROI#1 - patella, ROI#2 - trochlea, ROI#3 - lateral tibia plateau); b: Model fitting for steady-state signals vs. RF pulse width (bSSFPv) and flip angles (SPGR/bSSFP0,180), and corresponding ΔBIC (mcDESPOT - mcRISE) values. Note growing of bSSFPv signal due to decreasing MT saturation with increasing RF pulse width.

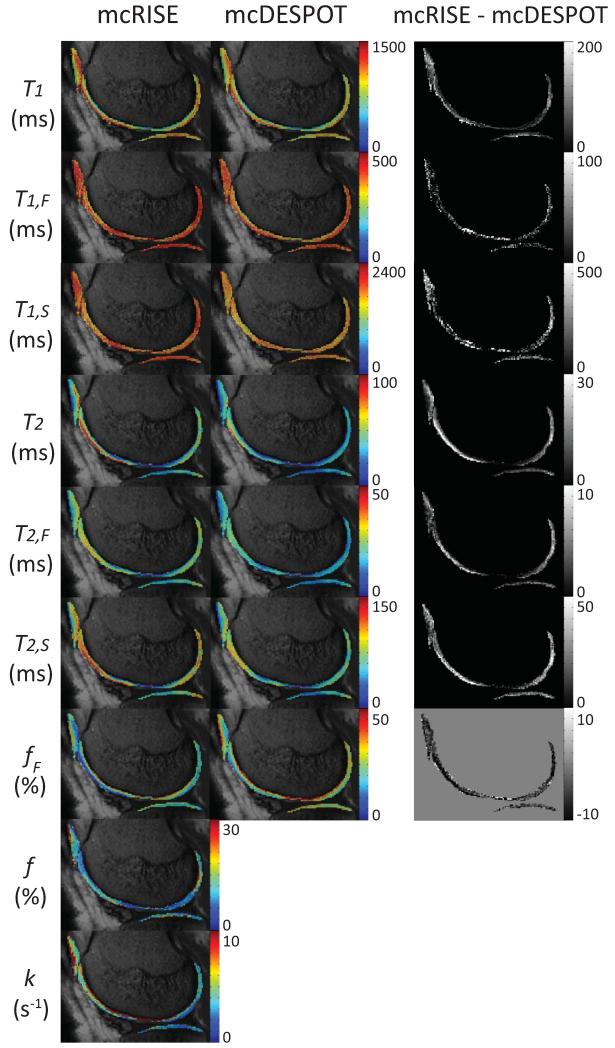

Figure 7 shows a sagittal image slice from a 28 years old male volunteer superimposed with standard single-component T1 and T2 and multi-component T1,F, T1,S, T2,F, T2,S and fF maps obtained from mcDESPOT and mcRISE, and additional f and k maps obtained from mcRISE (left two columns). The difference maps (rightmost column) confirm our simulation results that mcDESPOT underestimates T1, T2, T1,F, T1,S, T2,F and T2,S and overestimates fF when compared to mcRISE. The outlying parameter values are observed at the deep and superficial layer of cartilage surfaces which might be caused by partial volume averaging with synovial fluid and subchondral bone marrow. These qualitative observations are further illustrated by quantitative ROI analysis of parameter values in three healthy volunteers which are shown in Table 1. In all analyzed cartilage sub-regions, mcRISE provided higher single-component T1, T2 and multi-component T1,F, T1,S, T2,F, and T2,S values and lower fF values when compared to values obtained using mcDESPOT. Figure 7 also demonstrates significant variability of multi-component T1/T2 parameters and qMT parameters across different cartilage sub-regions, which was consistent among all three volunteers.

Figure 7.

A sagittal slice through the parameter maps obtained from mcRISE and mcDESPOT for a 28 years old male volunteer. Spatial variability of these parameters is obvious across different cartilage sub-regions. Similar to the numerical simulations, mcRISE provides higher T1, T1,F, T1,S, T2, T2,F and T2,S values and lower fF values when compared to values obtained from mcDESPOT.

Table 1.

Comparison of model parameter values obtained with mcRISE and mcDESPOT for in-vivo cartilage imaging. The mean value and standard deviation were obtained from the three healthy volunteers.

| Parameters | Patella | Trochlea | Lateral Tibia Plateau | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mcDESPOT | mcRISE | mcDESPOT | mcRISE | mcDESPOT | mcRISE | |

| T1 [ms] | 1063 (53.1) | 1166 (24.5) | 954 (27.2) | 1040 (51.2) | 1038 (42.1) | 1133 (39.1) |

| T1,F [ms] | 383 (12.5) | 412 (7.2) | 390 (26.3) | 401 (31.5) | 384 (19.3) | 417 (22.6) |

| T1,S [ms] | 1779 (96.1) | 1853 (55.1) | 1656 (102.3) | 1690 (88.5) | 1788 (52.1) | 1811 (87.3) |

| T2 [ms] | 34.4 (1.1) | 43 (1.9) | 48.2 (4.5) | 57.8 (0.5) | 26.1 (1.8) | 33.9 (2.6) |

| T2,F [ms] | 16.4 (2.6) | 23.7 (1.3) | 24.4 (2.8) | 31.2 (3.1) | 17.8 (2.5) | 21.5 (1.9) |

| T2,S [ms] | 71.9 (12.4) | 84.7 (10.0) | 76.6 (0.9) | 102.2 (5.9) | 61.3 (12.1) | 73.1 (15.9) |

| fF [%] | 31.1 (1.3) | 23.5 (1.2) | 29.9 (0.4) | 19.5 (0.3) | 35.7 (2.4) | 23.2 (2.5) |

| f [%] | - | 12.3 (1.2) | - | 13.3 (0.7) | - | 18.3 (6.0) |

| k [s−1] | - | 4.1 (0.8) | - | 4.9 (0.3) | - | 2.7 (0.2) |

DISCUSSION

In this work, we demonstrated using a cartilage tissue model that the MT effect between water and macromolecule protons may significantly bias parameters estimated by mcDESPOT. Similar to its effect on standard single-component T2 estimation from steady-state measurements (25), MT causes significant reduction of apparent T2 values of the fast-relaxing and slow-relaxing mcDESPOT components. Importantly, the fraction of the fast-relaxing water fF, the main parameter of interest in multi-component relaxometry approaches, was found to be most affected by MT exchange with overestimation by up to 41.2% in our simulations. These results support previous experimental observations of reduced T2,S and increased fF in macromolecule-rich tissues (28). Moreover, our simulations demonstrate that fF measured using mcDESPOT is influenced in a linear manner by the macromolecular proton fraction f (Fig. 5), and, therefore, the estimated fF will likely reflect macromolecular content in addition to the fast-relaxing water fraction. These results explain the significant positive correlations between macromolecular content and fF observed experimentally in other macromolecule-rich tissues such as brain white matter (43).

To correct MT effects, we proposed to expand the mcDESPOT two-pool model (F+S) with an additional exchanging macromolecular pool (B). To circumvent problems in model fitting associated with the increased number of free parameters, we developed a practical solution called mcRISE which employs two-stage parameter estimation. mcRISE first uses a two-pool MT model fit (B+W) to estimate the qMT parameters f and k and then applies them in the subsequent full three-pool (F+S+B) model fit. We demonstrated that such processing results in a multi-fold reduction of MT-induced biases observed in mcDESPOT parameters and, in particular, reduces bias in fF from 41.2% to 6%. Importantly, in addition to significant bias reduction, mcRISE removes the linear dependence of multi-component T2 estimates on the macromolecular proton fraction f, which may increase the parameters specificity to the T2 characteristics and fractions of the individual water compartments.

mcRISE incurs a scan time increase to acquire extra VRF measurements, which is not included into the mcDESPOT fit because RF pulse width affects its parameter estimates in a complicated way (44). However, mcRISE yields additional parameters related to MT exchange including f and k, which were shown in previous studies to be significantly different between asymptomatic volunteers and patients with osteoarthritis (45,46) and thus may be important for more complete characterization of the cartilage extracellular matrix. To estimate qMT parameters, mcRISE performs simultaneous fit of the two-pool MT model to all acquired measurements (VFA SPGR, bSSFP0, and bSSFP180 and VRF bSSFPv). This approach is a modification of a previously proposed qMTI approach of Gloor et al (27) in which model fit included only VFA bSSFP180 and VRF bSSFPv along with a pre-estimated single-compartment T1 from VFA SPGR. Such modification may have several distinct advantages if mcRISE is considered as a qMT technique. The inclusion of VFA SPGR into a combined mcRISE fit may avoid limitations of the single-compartment T1 approximation which has been previously shown to affect the accuracy of qMT-based T1, f, and k estimates (24). Similarly to mcDESPOT, mcRISE processing relies on additional bSSFP acquisition with no phase-cycling (bSSFP0) to perform B0 mapping (Fig. 2), which may reduce sensitivity of qMT parameter estimates to B0 (41). Similarly, additional VRF bSSFP dataset without RF phase-cycling may be required to provide robust estimation of qMT parameters in areas of significant off-resonance bands. Accuracy of both qMT approaches, however, may be potentially affected by several factors including assumptions about T2,B and saturation line estimation at on-resonance (27). These problems may be potentially avoided by modifying mcRISE to include standard off-resonance qMT measurements and estimation (24,39) as the first step of the fitting process (Fig. 2). Comparison of both on-resonance and off-resonance qMT approaches in context of efficient MT-corrected multi-component T2 relaxometry is a subject of future research. Another potential unaccounted source of bias is the finite pulse effect for longer RF pulses in VRF bSSFP acquisitions, which require a modification of the mcRISE equations similar to other approaches (23,47).

While our work primarily targets aspects of accurate modeling of multi-component T2 relaxometry from steady-state signals in the presence of macromolecular protons, further validation of the mcRISE method is needed prior to its use in in-vivo imaging studies. Comparison of mcRISE parameters with parameters obtained using multiple spin-echo T2 spectra, a standard method for in-vivo neural imaging, would be extremely difficult when evaluating cartilage in-vivo due to the high sensitivity of the standard multiple spin-echo method to SNR and the significantly decreased voxel volume required for cartilage imaging (48). Moreover, such comparison may be complicated by the fact that the multiple spin-echo method does not take into account inter-compartmental exchange which has been shown to significantly influence T2 estimates (49,50). Further, the validation of mcRISE is complicated by the lack of adequate physical phantoms sufficient to represent all model components simultaneously including water (F and S) and macromolecular (B) proton compartments. The existing phantoms are sufficient to study either MT effects (B+S model) (i.e., agarose, gelatin, and cross-linked bovine serum albumin (51,52)), or multi-component relaxometry in the absence of macromolecular protons (F+S model) (i.e., cream (53)). One valid validation strategy is to perform correlation analysis with histological, biochemical, and microstructural parameters of the cartilage extracellular matrix ex-vivo to further establish the usefulness of multi-component T2 measurements for evaluating articular cartilage. Next, we considered a three-pool (B+F+S) model approximation of a more complex cartilage tissue model (11). Hence, further NMR-based validation of the simplified model is required to establish its suitability to model signals from steady-state measurements. Further simplifications of the three-pool model may be required when the mcRISE method is applied to characterize neural tissues. In neural applications, the extra magnetization pathway between slow relaxing water and macromolecular proton pools is typically ignored to reflect the fact that short T2 water is the source of primary MT exchange within myelin (54,55). Finally, the mcRISE model may be expanded with additional, non-exchanging compartments to correct for partial volume averaging with subchondral bone marrow and synovial fluid similar to other relaxometric and qMT approaches (56,57).

Despite being biased by the MT effect, mcDESPOT parameters consistently have shown promising results in a number of clinical applications. In neural imaging, the short T2 water fraction measured using mcDESPOT has been found to be a useful biometric for characterizing longitudinal white matter development during early childhood (14,15) and white matter demyelination in multiple sclerosis (16,17). This parameter has also been found to provide superior diagnostic performance compared to traditional single-component T2 for distinguishing between normal and degenerative cartilage in human subjects (19). Hence, the practical value of correcting MT-induced biases in mcDESPOT estimates has to be confirmed in additional studies involving similar patient groups. At the same time, the anticipated improvement in specificity of multi-component relaxometry using mcRISE may allow better interpretation of the results of these previous studies to elucidate the sources of the observed changes (i.e. macromolecular content versus relative fraction of short T2 water component) and to relate them to the similarly encouraging results of qMT studies in multiple sclerosis (58) and osteoarthritis (46).

CONCLUSIONS

In this paper, we demonstrated that mcDESPOT parameters may be significantly biased in tissues with macromolecular protons, which is consistent with previous experimental findings. In particular, apparent fraction of fast relaxing water fF, the key parameter of interest, increases significantly with macromolecule content, which may create difficulties in interpretation of this parameter in macromolecule-rich tissues. mcRISE technique proposed in this paper expands the mcDESPOT model with an additional macromolecular proton pool to model these effects. mcRISE decouples multi-component T1/T2 and quantitative MT parameters and provides multi-fold reduction of MT-induced errors. Relaxometric and qMT parameters estimated by mcRISE may provide a new set of biomarkers for assessing the cartilage extracellular matrix in-vivo.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We gratefully acknowledge support provided by NIH NIAMS U01AR059514-03 and NIH R01NS065034 funds, GE Healthcare (Waukesha, WI) and the University of Wisconsin Radiology Research Fund.

REFERENCES

- 1.Crema MD, Roemer FW, Marra MD, Burstein D, Gold GE, Eckstein F, Baum T, Mosher TJ, Carrino JA, Guermazi A. Articular cartilage in the knee: current MR imaging techniques and applications in clinical practice and research. Radiographics. 2011;31(1):37–61. doi: 10.1148/rg.311105084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Choi JA, Gold GE. MR imaging of articular cartilage physiology. Magn Reson Imaging Clin N Am. 2011;19(2):249–282. doi: 10.1016/j.mric.2011.02.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dunn TC, Lu Y, Jin H, Ries MD, Majumdar S. T2 relaxation time of cartilage at MR imaging: comparison with severity of knee osteoarthritis. Radiology. 2004;232(2):592–598. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2322030976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Apprich S, Welsch GH, Mamisch TC, Szomolanyi P, Mayerhoefer M, Pinker K, Trattnig S. Detection of degenerative cartilage disease: comparison of high-resolution morphological MR and quantitative T2 mapping at 3.0 Tesla. Osteoarthritis and cartilage / OARS, Osteoarthritis Research Society. 2010;18(9):1211–1217. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2010.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liess C, Lusse S, Karger N, Heller M, Gluer CC. Detection of changes in cartilage water content using MRI T2-mapping in vivo. Osteoarthritis and cartilage / OARS, Osteoarthritis Research Society. 2002;10(12):907–913. doi: 10.1053/joca.2002.0847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nishioka H, Hirose J, Nakamura E, Oniki Y, Takada K, Yamashita Y, Mizuta H. T1rho and T2 mapping reveal the in vivo extracellular matrix of articular cartilage. Journal of magnetic resonance imaging: JMRI. 2012;35(1):147–155. doi: 10.1002/jmri.22811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mosher TJ, Smith H, Dardzinski BJ, Schmithorst VJ, Smith MB. MR imaging and T2 mapping of femoral cartilage: in vivo determination of the magic angle effect. AJR American journal of roentgenology. 2001;177(3):665–669. doi: 10.2214/ajr.177.3.1770665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reiter DA, Roque RA, Lin PC, Irrechukwu O, Doty S, Longo DL, Pleshko N, Spencer RG. Mapping proteoglycan-bound water in cartilage: Improved specificity of matrix assessment using multiexponential transverse relaxation analysis. Magn Reson Med. 2011;65(2):377–384. doi: 10.1002/mrm.22673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reiter DA, Lin PC, Fishbein KW, Spencer RG. Multicomponent T2 relaxation analysis in cartilage. Magn Reson Med. 2009;61(4):803–809. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zheng S, Xia Y. On the measurement of multi-component T2 relaxation in cartilage by MR spectroscopy and imaging. Magnetic resonance imaging. 2010;28(4):537–545. doi: 10.1016/j.mri.2009.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lattanzio PJ, Marshall KW, Damyanovich AZ, Peemoeller H. Macromolecule and water magnetization exchange modeling in articular cartilage. Magn Reson Med. 2000;44(6):840–851. doi: 10.1002/1522-2594(200012)44:6<840::aid-mrm4>3.0.co;2-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Whittall KP, MacKay AL, Graeb DA, Nugent RA, Li DK, Paty DW. In vivo measurement of T2 distributions and water contents in normal human brain. Magn Reson Med. 1997;37(1):34–43. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910370107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Deoni SC, Rutt BK, Arun T, Pierpaoli C, Jones DK. Gleaning multicomponent T1 and T2 information from steady-state imaging data. Magn Reson Med. 2008;60(6):1372–1387. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dean DC, O’Muircheartaigh J, Dirks H, Waskiewicz N, Walker L, Doernberg E, Piryatinsky I, Deoni SC. Characterizing longitudinal white matter development during early childhood. Brain Struct Funct. 2014 doi: 10.1007/s00429-014-0763-3. doi: 10.1007/s00429-014-0763-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Deoni SC, Dean DC, O’Muircheartaigh J, Dirks H, Jerskey BA. Investigating white matter development in infancy and early childhood using myelin water faction and relaxation time mapping. Neuroimage. 2012;63(3):1038–1053. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2012.07.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kolind S, Matthews L, Johansen-Berg H, Leite MI, Williams SC, Deoni S, Palace J. Myelin water imaging reflects clinical variability in multiple sclerosis. Neuroimage. 2012;60(1):263–270. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.11.070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kitzler HH, Su J, Zeineh M, Harper-Little C, Leung A, Kremenchutzky M, Deoni SC, Rutt BK. Deficient MWF mapping in multiple sclerosis using 3D whole-brain multi-component relaxation MRI. Neuroimage. 2012;59(3):2670–2677. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.08.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu F, Chaudhary R, Hurley SA, Munoz Del Rio A, Alexander AL, Samsonov A, Block WF, Kijowski R. Rapid multicomponent T2 analysis of the articular cartilage of the human knee joint at 3.0T. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2014;39(5):1191–1197. doi: 10.1002/jmri.24290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu F, Spencer RG, Block W, Kijowski R. Multi-Component T2 Analysis of Articular Cartilage in Osteoarthritis Patients using mcDESPOT at 3.0T; Proc Intl Soc Mag Reson Med.; Milan, Italy. 2014; abstract 5262. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim DK, Ceckler TL, Hascall VC, Calabro A, Balaban RS. Analysis of water-macromolecule proton magnetization transfer in articular cartilage. Magn Reson Med. 1993;29(2):211–215. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910290209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gray ML, Burstein D, Lesperance LM, Gehrke L. Magnetization transfer in cartilage and its constituent macromolecules. Magn Reson Med. 1995;34(3):319–325. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910340307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wachsmuth L, Juretschke HP, Raiss RX. Can magnetization transfer magnetic resonance imaging follow proteoglycan depletion in articular cartilage? MAGMA. 1997;5(1):71–78. doi: 10.1007/BF02592269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ou X, Gochberg DF. MT effects and T1 quantification in single-slice spoiled gradient echo imaging. Magn Reson Med. 2008;59(4):835–845. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mossahebi P, Yarnykh VL, Samsonov A. Analysis and correction of biases in cross-relaxation MRI due to biexponential longitudinal relaxation. Magn Reson Med. 2013 doi: 10.1002/mrm.24677. doi: 10.1002/mrm.24677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bieri O, Scheffler K. On the origin of apparent low tissue signals in balanced SSFP. Magn Reson Med. 2006;56(5):1067–1074. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Crooijmans HJ, Gloor M, Bieri O, Scheffler K. Influence of MT effects on T(2) quantification with 3D balanced steady-state free precession imaging. Magn Reson Med. 2011;65(1):195–201. doi: 10.1002/mrm.22326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gloor M, Scheffler K, Bieri O. Quantitative magnetization transfer imaging using balanced SSFP. Magn Reson Med. 2008;60(3):691–700. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang J, Kolind SH, Laule C, Mackay AL. Comparison of myelin water fraction from multiecho T2 decay curve and steady-state methods. Magn Reson Med. 2014 doi: 10.1002/mrm.25125. doi: 10.1002/mrm.25125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Samsonov A, Alexander AL, Mossahebi P, Wu YC, Duncan ID, Field AS. Quantitative MR imaging of two-pool magnetization transfer model parameters in myelin mutant shaking pup. Neuroimage. 2012;62(3):1390–1398. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2012.05.077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stikov N, Keenan KE, Pauly JM, Smith RL, Dougherty RF, Gold GE. Cross-relaxation imaging of human articular cartilage. Magn Reson Med. 2011;66(3):725–734. doi: 10.1002/mrm.22865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stanisz GJ, Odrobina EE, Pun J, Escaravage M, Graham SJ, Bronskill MJ, Henkelman RM. T1, T2 relaxation and magnetization transfer in tissue at 3T. Magn Reson Med. 2005;54(3):507–512. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McConnell HM. Reaction Rates by Nuclear Magnetic Resonance. The Journal of Chemical Physics. 1958;28:430–431. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Haacke EM, Brown RW, Thompson MR, Venkatesan R. Magnetic Resonance Imaging: Physical Principles and Sequence Design. John Wiley & Sons; New York: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Scheffler K, Hennig J. Is TrueFISP a gradient-echo or a spin-echo sequence? Magn Reson Med. 2003;49(2):395–397. doi: 10.1002/mrm.10351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Graham SJ, Henkelman RM. Understanding pulsed magnetization transfer. J Magn Reson Imaging. 1997;7(5):903–912. doi: 10.1002/jmri.1880070520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Morrison C, Henkelman RM. A model for magnetization transfer in tissue (vol 33, pg 475, 1995) Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 1996;35(2):277–277. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910330404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lankford CL, Does MD. On the inherent precision of mcDESPOT. Magn Reson Med. 2013;69(1):127–136. doi: 10.1002/mrm.24241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Henkelman RM, Huang X, Xiang QS, Stanisz GJ, Swanson SD, Bronskill MJ. Quantitative interpretation of magnetization transfer. Magn Reson Med. 1993;29(6):759–766. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910290607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yarnykh VL, Yuan C. Cross-relaxation imaging reveals detailed anatomy of white matter fiber tracts in the human brain. Neuroimage. 2004;23(1):409–424. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.04.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Deoni SC. High-resolution T1 mapping of the brain at 3T with driven equilibrium single pulse observation of T1 with high-speed incorporation of RF field inhomogeneities (DESPOT1-HIFI) J Magn Reson Imaging. 2007;26(4):1106–1111. doi: 10.1002/jmri.21130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Deoni SC. Transverse relaxation time (T2) mapping in the brain with off-resonance correction using phase-cycled steady-state free precession imaging. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2009;30(2):411–417. doi: 10.1002/jmri.21849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.McQuarrie ADR, Tsai C-L. Regression and time series model selection. xxi. World Scientific; Singapore; River Edge, N.J.: 1998. p. 455. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Samson RS, Deoni SC, Wheeler-Kingshott CA. Correlation of potential myelin measures from quantitative Magnetisation Transfer (qMT) and multi-component Driven Equilibrium Single Pulse Observation of T1 and T2 (mcDESPOT); Proc Intl Soc Mag Reson Med.; Hawaii, USA. 2009; abstract 4476. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhang J, Kolind SH, Laule C, MacKay AL. How does magnetization transfer influence mcDESPOT results? Magn Reson Med. 2014 doi: 10.1002/mrm.25520. doi: 10.1002/mrm.25520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mossahebi P, Chaudhary R, Sritanyaratana N, Block WF, Samsonov AA, Kijowski R. Factors Influencing Quantitative Magnetization Transfer (QMT) Parameters of Articular Cartilage; Proc Intl Soc Mag Reson Med.; Salt Lake City, USA. 2013; abstract 431. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sritanyaratana N, Samsonov A, Mossahebi P, Wilson JJ, Block WF, Kijowski R. Cross-relaxation imaging of human patellar cartilage in vivo at 3.0T. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2014;22(10):1568–1576. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2014.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bieri O, Scheffler K. SSFP signal with finite RF pulses. Magn Reson Med. 2009;62(5):1232–1241. doi: 10.1002/mrm.22116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fenrich FR, Beaulieu C, Allen PS. Relaxation times and microstructures. NMR Biomed. 2001;14(2):133–139. doi: 10.1002/nbm.685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Harkins KD, Dula AN, Does MD. Effect of intercompartmental water exchange on the apparent myelin water fraction in multiexponential T2 measurements of rat spinal cord. Magn Reson Med. 2012;67(3):793–800. doi: 10.1002/mrm.23053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dortch RD, Harkins KD, Juttukonda MR, Gore JC, Does MD. Characterizing inter-compartmental water exchange in myelinated tissue using relaxation exchange spectroscopy. Magn Reson Med. 2013;70(5):1450–1459. doi: 10.1002/mrm.24571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Koenig SH, Brown RD. A molecular theory of relaxation and magnetization transfer: application to cross-linked BSA, a model for tissue. Magn Reson Med. 1993;30(6):685–695. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910300606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Koenig SH, Brown RD, Ugolini R. Magnetization transfer in cross-linked bovine serum albumin solutions at 200 MHz: a model for tissue. Magn Reson Med. 1993;29(3):311–316. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910290306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jones C, MacKay A, Rutt B. Bi-exponential T2 decay in dairy cream phantoms. Magn Reson Imaging. 1998;16(1):83–85. doi: 10.1016/s0730-725x(97)00250-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Stanisz GJ, Kecojevic A, Bronskill MJ, Henkelman RM. Characterizing white matter with magnetization transfer and T(2) Magn Reson Med. 1999;42(6):1128–1136. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1522-2594(199912)42:6<1128::aid-mrm18>3.0.co;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bjarnason TA, Vavasour IM, Chia CL, MacKay AL. Characterization of the NMR behavior of white matter in bovine brain. Magn Reson Med. 2005;54(5):1072–1081. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Deoni SC, Matthews L, Kolind SH. One component? Two components? Three? The effect of including a nonexchanging “free” water component in multicomponent driven equilibrium single pulse observation of T1 and T2. Magn Reson Med. 2013;70(1):147–154. doi: 10.1002/mrm.24429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mossahebi P, Alexander AL, Field A, Samsonov A. Analysis and Optimization of Quantitative Magnetization Transfer Imaging Considering the Effect of Non-Exchanging Component; Proc Intl Soc Mag Reson Med.; Milan, Italy. 2014; abstract 207. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yarnykh VL, Bowen JD, Samsonov A, Repovic P, Mayadev A, Qian P, Gangadharan B, Keogh BP, Maravilla KR, Henson LK. Fast Whole-Brain Three-dimensional Macromolecular Proton Fraction Mapping in Multiple Sclerosis. Radiology. 2014:140528. doi: 10.1148/radiol.14140528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]