Abstract

To confirm our hypothesis that the sex and age of cynomolgus monkeys influences the effect of training, we employed a new training technique designed to increase the animal’s affinity for animal care personnel. During 151 days of training, monkeys aged 2 to 10 years accepted each 3 raisins/3 times/day, and communicated with animal care personnel (5 times/day). Behavior was scored using integers between −1 and 5. Before training, 35 of the 61 monkeys refused raisins offered directly by animal care personnel (Score −1, 0 and 1). After training, 28 of these 35 monkeys (80%) accepted raisins offered directly by animal care personnel (>Score 2). The mean score of monkeys increased from 1.2 ± 0.1 to 4.3 ± 0.2. The minimum training period required for monkeys to reach Score 2 was longer for females than for males. After 151 days, 6 of the 31 females and 1 of the 30 males still refused raisins offered directly by animal care personnel. Beneficial effects of training were obtained in both young and adult monkeys. These results indicate that our new training technique markedly improves the affinity of monkeys for animal care personnel, and that these effects tend to vary by sex but not age. In addition, abnormal behavior and symptoms of monkeys were improved by this training.

Keywords: animal welfare, monkey, raisins, training

Introduction

Monkeys are highly intelligent, social, and mentally active animals that present unique hazards to animal care personnel such as biting and scratching, which both carry a high risk of zoonotic infection. During experiments, sensitivity is required to enhance both the well-being of the monkeys as well as the safety of animal care personnel. Techniques using positive reinforcement training (PRT) enhance the care and welfare of monkeys [9, 15]. Successful PRT protocols that reduce stress on monkeys and animal care personnel have been described for the collection of blood samples [4, 12, 13].

Here, we attempt to train monkeys to remain unrestrained during blood collection or drug administrations by building a trusting relationship between them and animal care personnel. We report the results of training using raisins and communication to improve the affinity of cymologus monkeys for animal care personnel prior to PRT.

Materials and Methods

Animals

All training procedures were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Astellas Pharma Inc., which is accredited by the Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care (AAALAC) International.

Healthy cynomolgus monkeys (31 females and 30 males) aged 2 to 10 years were used. Monkeys were housed in stainless steel cages (630 × 650 × 1,180 mm) with a 12:12 h light-dark cycle (light on from 07:00 to 19:00 h) in a controlled temperature (25 ± 1°C) and humidity (60 ± 5%) environment in compliance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals [6]. HEPA-filtered 100% fresh air was used with 12.1 to 22.0 changes per hour. Monkeys were fed standard laboratory food (approximately 100 g/animal/day, PS-A; Oriental Yeast, Tokyo, Japan), and tap water was available ad libitum during training. As environmental enrichment programs, music from a local radio station was played from 13:00 to 15:00 h, and the monkeys had access to toys such as Dumbbell, Monkey Shine Mirrors, and Kong (Bio-Serv, Frenchtown, NJ). Before training, monkeys were determined to be healthy based on general appearance, activity, and a tuberculosis skin test. All of the monkeys were serologically negative for B virus. No animals were sacrificed in the study.

Training

Before training, monkeys were offered a raisin once a day at 9:00, and engaged in communication with animal care personnel at 9:00, 11:00 and 15:00. During the training program, monkeys were offered raisins at 9:00, 11:00 and 15:00, and engaged in communication with animal care personnel at 9:00, 11:00, 13:00, 15:00 and 17:00 from September 2, 2013 to January 31, 2014 (Mon-Fri). Animal care personnel provided laboratory food (PS-A) and no more than 5 raisins per day. The caloric content of 100 g of PS-A was 365.8 kcal, and that of 5 raisins was 7.3 kcal. Given that the cumulative caloric content of 5 raisins was relatively low compared to PS-A, the monkeys did not receive an excessive intake of calories. One animal care personnel implemented a training program. During the 1- to 2-min observation period, the effect of training was scored at 13:00 h, as follows: Score −1, scared to animal care personnel; Score 0, refusal to eat raisin in the presence of animal care personnel; Score 1, sampling of raisin in the presence of personnel when raisins served on grid of the cage; Score 2, acceptance of raisin from hand to hand via the upper part of the cage; Score 3, acceptance of raisin from hand to mouth via the upper part of the cage; Score 4, acceptance of raisin from hand to hand via the lower part of the cage; and Score 5, acceptance of raisin from hand to mouth via the lower part of the cage. Caution for each score is shown in Table 1. Monkeys with a score of more than Scores 2 were considered to have a positive affinity for animal care personnel when performing tasks. The minimum days required for monkeys refused raisins offered directly by animal care personnel to accept raisins were calculated from observed score. Effect of training on affinity of monkeys for animal care personnel by sex group or age group of monkeys was indicated as change in score. At this time, abnormal behavior and symptoms were also recorded.

Table 1. Caution for each step of training.

| Caution | |

|---|---|

| Score -1 | Educate monkeys that raisins taste good |

| Score 0 | Shorten mental distance by degrees between monkeys and animal care personnel when monkeys eat raisins |

| Score 1 | Keep animal care personnel’s hands close to near the cage when offering raisins from outside of the cage |

| Score 2 | Prolong time when monkeys are close to animal care personnel |

| Score 3 | Offer raisins from lower region of the cage |

| Score 4 | Offer raisins when in close proximity to monkey’s face |

| Score 5 | Make contact with monkey’s hands and face gently when they are eating raisins |

Statistical analysis

Results are expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Statistical significance was analyzed using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test or the Wilcoxon rank sum test. The difference between groups was considered statically significant when P<0.05.

Results

Effect of training in cynomologus monkeys

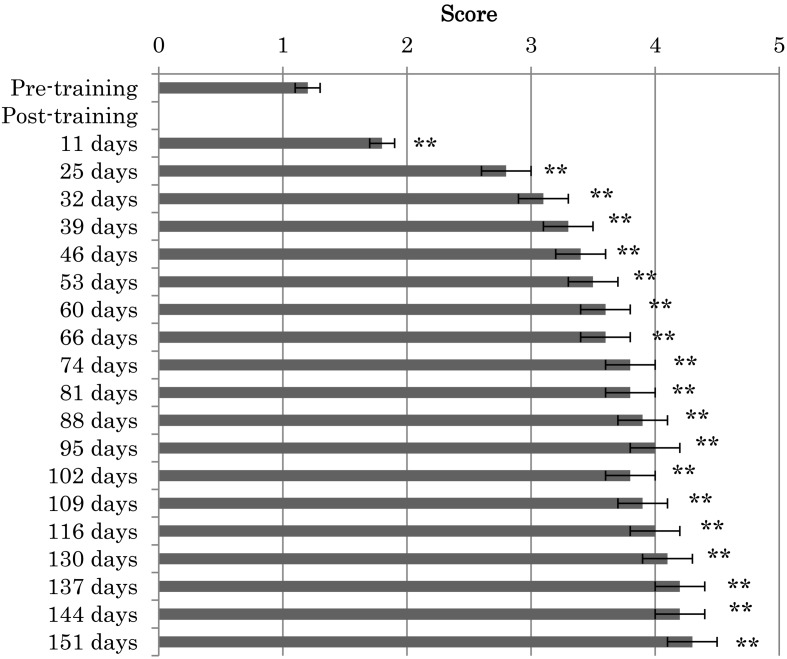

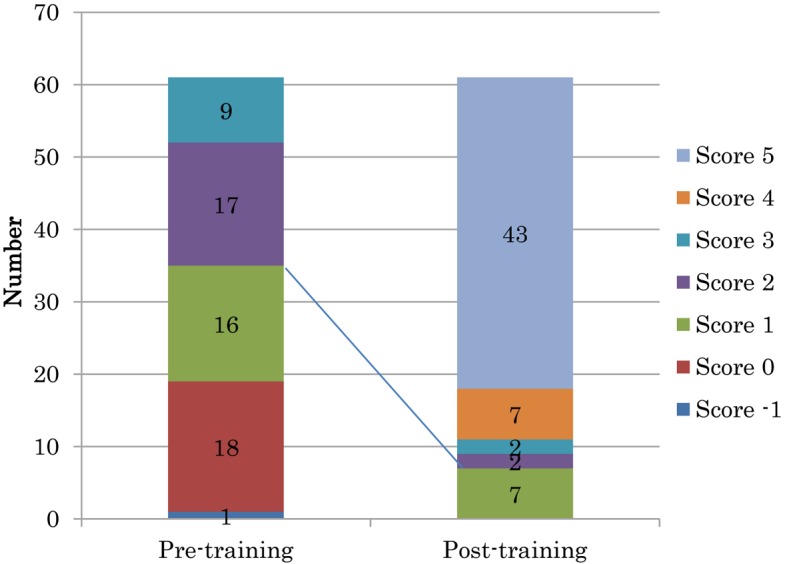

Improved affinity of cynomolgus monkeys for animal care personnel was evaluated based on the above scores. Before training, 35 of the 61 monkeys refused raisins offered directly from animal care personnel (Score −1, 0 and 1) (Fig. 1). After 151 days training, 28 of these 35 monkeys (80%) accepted raisins offered directly by animal care personnel (>Score 2). Before training, the 26 monkeys with a positive affinity for animal care personnel had a score of 2 (n=17) or 3 (n=9). After training, these 26 monkeys had score of 4 (n=1) or 5 (n=25). Following training, the score of each monkey increased, as did the mean score for all monkeys: from 1.2 ± 0.1 to 4.3 ± 0.2 (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

Distribution of affinity for animal care personnel pre- and post-training in monkeys. Results are shown number of animals in each score. Monkeys with a score of more than Scores 2 were considered to have a positive affinity for animal care personnel when performing tasks.

Fig. 2.

Change in score during the training to improve affinity of monkeys for animal care personnel. Results are shown as score. Values are means ± SEM (n=61). Statistical significance was analyzed using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test. **P<0.01 indicates a significant difference from the pre-training value.

The minimum period of time required to reach Score 2 was 52.4 ± 7.9 days (n=12) for monkeys with an initial score of 0, and 22.7 ± 4.5 days (n=15) for those with an initial score of 1 (Table 2). The minimum period of time required for monkeys to reach Score 2 by training tended to be longer for females than for males, with 6 of the 31 females and 1 of the 30 males refusing raisin offered directly from animal care personnel even at the end of the training period. After training, female monkeys with initial score of 0 and 1 reached score 2.6 ± 0.4 and 4.4 ± 0.5, respectively (Table 3). In contradistinction to female monkeys, male monkeys with initial score of 0 and 1 reached score 3.7 ± 0.6 and all Score 5, respectively.

Table 2. The minimum days required for monkeys to accept raisins offered directly by animal care personnel (Scores 2, 3, 4 and 5).

| Sex | Number | Time (days) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Subjects with Score 0 pre-training | |||

| Female | 7 | 60.0 ± 12.2 | |

| Male | 5 | 41.8 ± 7.2 | |

| All | 12 | 52.4 ± 7.9 | |

| Subjects with Score 1 pre-training | |||

| Female | 10 | 25.0 ± 6.3 | |

| Male | 5 | 18.0 ± 4.4 | |

| All | 15 | 22.7 ± 4.5 | |

Results are shown as the minimum training period required for monkeys to reach Score 2. Values are means ± SEM. Statistical significance between female and male was analyzed using the Wilcoxon rank sum test.

Table 3. Effect of training on affinity of monkeys for animal care personnel by sex group of monkeys.

| Sex | Number | Score Post-training 151 days |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Subjects with Score 0 pre-training | |||

| Female | 12 | 2.6 ± 0.4 | |

| Male | 6 | 3.7 ± 0.6** | |

| Subjects with Score 1 pre-training | |||

| Female | 11 | 4.4 ± 0.5 | |

| Male | 5 | All Score 5 | |

Results are shown as score. Values are means ± SEM. Statistical significance was analyzed using the Wilcoxon rank sum test. **P<0.01 indicates a significant difference from the female monkeys value.

The 61 monkeys were segregated into three groups based on age ranges of 2 to 3, 4 to 6, and 7 to 10 years. After 151 days training, the mean score of the 29 monkeys aged 2 to 3 years increased from 0.6 ± 0.2 to 3.8 ± 0.3 (Table 4). Similarly, after 151 days of training, the mean score also increased in the 21 monkeys aged 4 to 6 years and 11 monkeys aged 7 to 10 years.

Table 4. Effect of training on affinity of monkeys for animal care personnel by age group of monkeys.

| Age (years) | Number | Score | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-training | Post-training 151 days | ||

| 2–3 | 29 | 0.6 ± 0.2 | 3.8 ± 0.3** |

| 4–6 | 21 | 1.9 ± 0.1 | 4.6 ± 0.2** |

| 7–10 | 11 | 1.6 ± 0.4 | 4.9 ± 0.1** |

Results are shown as score. Values are means ± SEM. Statistical significance was analyzed using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test. **P<0.01 indicates a significant difference from the pre-training value.

Improvement of abnormal behavior and symptoms during the training

Loose stool disappeared at an early stage of training in one animal that had frequent loose stool after arrival in our facility. Whole-body hair loss subsided after 4 months of training in another one animal. Aggressive behavior toward animal care personnel observed in 12 of the 61 monkeys was fully resolved within 2 weeks after training. Further, self-injury behavior such as self-biting with breaking the skin disappeared during 151 days training.

Discussion

PRT is reported to enhance the care and well-being of animals [1], and to help ease the process of obtaining blood and urine samples from rhesus macaques and chimpanzees [10, 13]. We hypothesized that animal’s sex and age influence the effect of training on monkeys to have an increased affinity for animal care personnel. Here, we trained laboratory-housed cynomolgus monkeys to have an affinity for animal care personnel as a part of PRT. Our new training technique markedly improved the affinity of monkeys for animal care personnel, and the effect of this technique tended to vary by sex but not age. In addition, abnormal behavior and symptoms were improved in monkeys by this training.

As the first step, the grid of the cage was coated with raisin paste. Monkeys were then shown that the raisin they held tasted good. Crushed raisins were then given to monkeys. Training monkeys to have an affinity for animal care personnel at our facility had an 80% success rate. Despite the suspension of training for the year-end and New Year holidays from Days 117 to 125 (December 28, 2013, to January 5, 2014), scores did not decrease after this period. Therefore, this new training technique is possible to switch to intermittent training which maintain affinity for humans and enhance the welfare of animals. Our new training technique is convenient means than other technique. Thus, this training is performed by a number of animal care personnel now. These results indicate that our training technique dose improve affinity of cynomolgus monkeys for animal care personnel.

Females exhibit a higher level of ability on variety of memory tasks than males [2, 7, 8, 14]. Sex differences were observed in degree of success in training mokeys [11], with males being more likely to respond than females. The results of the present study are consistent with these reported elsewhere in the literatures.

To our knowledge, no studies have reported young animals requiring a longer training period than adults. Changes in score of monkeys of different age groups were evaluated to determine the effect of training on affinity between monkeys and animal care personnel. In the present study, beneficial results for training were obtained in each age group, thereby confirming that the efficacy of the new training program does not depend on the monkey’s age.

In a previous study, PRT helps to reduce stereotypical behavior of monkeys in a proportion of adult female rhesus macaques housed in a research facility [5], and notably, PRT has also been used to reduce aggressive behavior among chimpanzees [3]. In addition, untrained animals tend to exhibit more self-scratching than trained animals [1]. These positive changes in the behavior and symptoms of monkeys indicate that PRT substantially reduces their stress levels [1]. In the present study, while we did observe abnormal behavior such as aggression and self-injury, such behaviors disappeared following short-term training. Further, the incidence of symptoms such as loose stool and whole-body hair loss were reduced in trained monkeys. Similarly, our novel training technique enhances the psychological well-being of monkeys and the safety of animal care personnel and researchers during handling procedures. If we use monkeys improving abnormal behavior in good health through the use of new training technique, PRT might get a good result in a short time.

In conclusion, our training improves the affinity of laboratory-housed cynomolgus monkeys for animal care personnel, with these effects tending to vary by sex but not age. In addition, our training technique improves abnormal behavior and symptoms in monkeys.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr. Yuji Sudo for valuable advice on this study. We are also grateful to Mr. Yuki Tachibana and Mr. Kaoru Takaura for their technical support with animal care during the project.

References

- 1.Bassett L., Buchanan-Smith H.M., McKinley J., Smith T.E.2003. Effects of training on stress-related behavior of the common marmoset (Callithrix jacchus) in relation to coping with routine husbandry procedures. J. Appl. Anim. Welf. Sci. 6: 221–233. doi: 10.1207/S15327604JAWS0603_07 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Birenbaum M., Kelly A.E., Levi-Keren M.1994. Stimulus features and sex differences in mental rotation test performance. Intelligence 19: 51–64. doi: 10.1016/0160-2896(94)90053-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bloomsmith M.A., Laule G.E., Alford P.L., Thurston R.H.1994. Using training to moderate chimpanzee aggression during feeding. Zoo Biol. 13: 557–566. doi: 10.1002/zoo.1430130605 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Coleman K., Pranger L., Maier A., Lambeth S.P., Perlman J.E., Thiele E., Schapiro S.J.2008. Training rhesus macaques for venipuncture using positive reinforcement techniques: a comparison with chimpanzees. J. Am. Assoc. Lab. Anim. Sci. 47: 37–41. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Coleman K., Maier A.2010. The use of positive reinforcement training to reduce stereotypic behavior in rhesus macaques. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 124: 142–148. doi: 10.1016/j.applanim.2010.02.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Committee for the Update of the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, andInstitute for Laboratory Animal Research. 2010. Environment, housing, and management. pp.41–103. In: Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, 8th ed. The National Academies Press, Washington, D.C. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eals M., Silverman I.1994. The hunter-gatherer theory of spatial sex differences: Proximate factors mediating the female advantage in recall of object arrays. Ethol. Sociobiol. 15: 95–105. doi: 10.1016/0162-3095(94)90020-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Herlitz A., Nilsson L.G., Bäckman L.1997. Gender differences in episodic memory. Mem. Cognit. 25: 801–811. doi: 10.3758/BF03211324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Laule G., Whittaker M.2007. Enhancing nonhuman primate care and welfare through the use of positive reinforcement training. J. Appl. Anim. Welf. Sci. 10: 31–38. doi: 10.1080/10888700701277311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Laule G.E., Thurston R.H., Alford P.L., Bloomsmith M.A.1996. Training to reliably obtain blood and urine samples from a diabetic chimpanzee (Pan troglodytes). Zoo Biol. 15: 587–591. doi: [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Reamer L.A., Haller R.L., Thiele E.J., Freeman H.D., Lambeth S.P., Schapiro S.J.2014. Factors affecting initial training success of blood glucose testing in captive chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes). Zoo Biol. 33: 212–220. doi: 10.1002/zoo.21123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Reinhardt V.1991. Training adult male rhesus monkey to actively cooperate during in-homecage venipuncture. Anim. Technol. 42: 11–17. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reinhardt V.2003. Working with rather than against macaques during blood collection. J. Appl. Anim. Welf. Sci. 6: 189–197. doi: 10.1207/S15327604JAWS0603_04 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stumpf H., Eliot J.1995. Gender-related differences in spatial ability and the κ factor of general spatial ability in a population of academically talented students. Pers. Individ. Dif. 19: 33–45. doi: 10.1016/0191-8869(95)00029-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Whittaker M., Laule G.2012. Training techniques to enhance the care and welfare of nonhuman primates. Vet. Clin. North Am. Exot. Anim. Pract. 15: 445–454. doi: 10.1016/j.cvex.2012.06.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]