Abstract

Colorectal cancer is one of the leading causes of cancer related deaths worldwide. Cullin 4B (CUL4B) is over-expressed in diverse cancer types. However, the function and precise molecular mechanism of CUL4B in colorectal cancer remains largely unknown. Therefore, in this study, we examined the expression of CUL4B in colorectal cancer cell lines and its effects on cellular proliferation and apoptosis, and the underlying mechanism was also explored. Our results showed that CUL4B was significantly overexpressed in colorectal cancer cell lines. Silencing CUL4B obviously inhibited proliferation and tumorigenicity of colorectal cancer cells both in vitro and in vivo, and it also promoted the apoptosis of colorectal cancer cells. Moreover, knockdown of CUL4B inhibited the expression of β-catenin, cyclin D1 and c-Myc in colorectal cancer cells. Taken together, these results showed that knockdown of CUL4B inhibit proliferation and promotes apoptosis of colorectal cancer cells through suppressing the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway. Therefore, CUL4B may represent a novel therapeutic target for colorectal cancer treatment.

Keywords: Cullin 4B (CUL4B), colorectal cancer, proliferation, apoptosis, Wnt/β-catenin pathway

Introduction

Colorectal cancer is the third leading cause of cancer associated death in the United States of America [1] and the second most prevalent cancer in China. Although the diagnosis and treatment of colorectal cancer have been improved in the past years, the efficacy of surgery and chemotherapy remains unsatisfactory. This is largely attributed to a lack of complete understanding of the exact cause and mechanisms for this malignancy. Therefore, further understanding of the molecular mechanisms of cancer progression and the development of new therapeutic tools based on these mechanisms are required.

Cullin-RING ligases (CRLs) complexes comprise the largest known class of ubiquitin ligases [2]. CRLs regulate diverse cellular processes, including cell cycle progression, transcription, signal transduction and development [3]. CRLs are multisubunit complexes composed of a cullin, RING protein and substrate-recognition subunit, which was linked by an adaptor. Cullin 4B (CUL4B) is a component of the Cullin 4B-Ring E3 ligase complex (CRL4B) that functions in proteolysis [4]. It has been reported that loss-of-function mutation in the X-linked CUL4B causes mental retardation, short statue, absence of speech and other phenotypes in humans [5,6], and Cul4b knockout mice are embryonically lethal [7]. With regard to cancer, CUL4B is over-expressed in diverse cancer types, including osteosarcoma [8], cervical carcinoma [9], hepatocellular carcinoma [10]. Most recently, Jiang et al reported that CUL4B mRNA and protein levels in colon cancer tissues were both higher than that in normal mucosae, and high CUL4B expression was closely associated with the depth of tumor invasion, lymph node metastasis, distant metastasis, histological differentiation, vascular invasion and advanced tumor stage [11]. The function and precise molecular mechanism of CUL4B in colorectal cancer, however, remains largely unknown. Therefore, in this study, we examined the expression of CUL4B in colorectal cancer cell lines and its effects on cellular proliferation and apoptosis, and the underlying mechanism was explored.

Materials and methods

Cell culture

Healthy human colon mucosa cell line (NCM460) and colorectal cancer cell lines (SW480, HT-29 and HCT116) were purchased from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA), and all the cell lines were maintained in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM; Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA), streptomycin (100 mg/ml), and penicillin (100 mg/ml). All cell lines were cultured at 37°C under 5% CO2.

RT-PCR

Total RNA was extracted from colorectal cancer tissues and cells using Trizol reagent (Abcam, Cambridge, UK) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. cDNA was synthesized from the extracted RNA (4 µg) using the EasyScript First-Strand cDNA Synthesis SuperMix kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). PCR amplification was performed using the following primers: CUL4B, 5’-CCTGGAGTTTGTAGGGTTTGAT-3’ (sense) and 5’-GAGACGGTGGTAGAAGATTTGG-3’ (antisense); and β-actin, 5’-TTAGTTGCGTTACACCCTTTC-3’ (sense) and 5’-ACCTTCACCGTTCCAGTTT-3’ (antisense). The PCR conditions included an initial denaturation step of 94°C for 2 min, followed by 35 cycles of 94°C for 30 s, 56°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 2 min, and a final elongation step of 72°C for 10 min.

Western blot

Total protein was extracted from colorectal cancer tissues and cells, then washed with ice-cold PBS and lysed with RIPA Cell Lysis Buffer (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA). The protein concentrations were determined by the BCA method. The samples (30 μg protein/lane) were separated on 10% SDS-PAGE and transferred onto polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membranes (Millipore, Boston, MA, USA). After blocking in TBS buffer (50 mmol/L NaCl, 10 mmol/L Tris, pH 7.4) containing 5% nonfat milk, the blots were incubated with primary antibodies (anti-CUL4B, anti-β-catenin, anti-cyclin D1, anti-c-Myc or β-actin) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA) at 4°C overnight. Membranes were then washed and incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies. Expression was visualized by using ECL Western blotting detection reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific, RockFord, IL, USA).

RNA interference-mediated knockdown of CUL4B and cell transfection

CUL4B siRNA were constructed by Gimma company in Shanghai, as follow: 5’-CAAUCUCCUUGUUUCAGAATT-3’; siRNA con vector (the random sequence as control that was not related to CUL4B mRNA) 5’-UUCUCCGAACGUGUCACGUTT-3’. For in vitro transfection, 5 × 104 cells were seeded in each cell of a 24-well micro-plate, grown for 24 h to reach 30%-50% confluence, and then incubated with a mixture of siRNA and Lipofectamine 2000 reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) in 100 μl serum-free DMEM, according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The transfection efficiency was examined by Western blot.

Cell proliferation assay

Cell proliferation was determined by 3-(4.5-methylthiozol-2yl)-2.5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay. Cells (3 × 103 cells/well) were seeded into 96-well plates and cultured for 24, 48, 72, and 96 h. MTT (10 ml) was added into each well, and cells were cultured for an additional 4 h. The culture media was removed and 200 ml DMSO (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) was added to each well. The absorbance at 570 nm was measured with a microplate reader (Takara Biotechnology, Dalian, China).

Cell apoptosis assay

The cell apoptotic ratio was measured by Annexin V-FITC and PI staining followed by analysis with flow cytometry (Beckman-Coulter, Brea, CA, USA). Briefly, cells (3 × 105) were seeded in six-well plates and allowed to adhere. Twenty-four hours later, the cells were harvested by centrifugation at 1,000 rpm for 5 min. The cell pellets were washed twice with PBS followed by fixation with 70% ice-cold ethanol and stored at -20°C overnight. The pellets were washed with cold PBS and stained with propidium iodide and Annexin V. Apoptotic cells were analyzed by FACSCalibur to define as those positive cells for Annexin V with or without PI staining.

Tumorigenicity assay

Male BALB/c nude mice were obtained (Shanghai Slac Laboratory Animal Co. Ltd, China) and bred under specific pathogen-free conditions. CUL4B knockdown cells (1 × 106) and their control cells were injected subcutaneously into the opposite flanks of the same mouse. The resulting tumors were measured once a week, and tumor volumes (mm3) were calculated using the following formula: volume = width2 × length × 0.5 [12]. Tumors were harvested 35 days after injection. Data were presented as tumor volumes and tumor weight (mean ± SD). Animal experiment was carried out with the approval of the ethics committee of Tianjin Medical University in accordance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

Statistical analysis

All results are reported as means ± SD. Statistical analysis involved Student’s t-test for the comparison of two groups or one-way ANOVA for multiple comparisons. P < 0.05 was considered to be significant.

Results

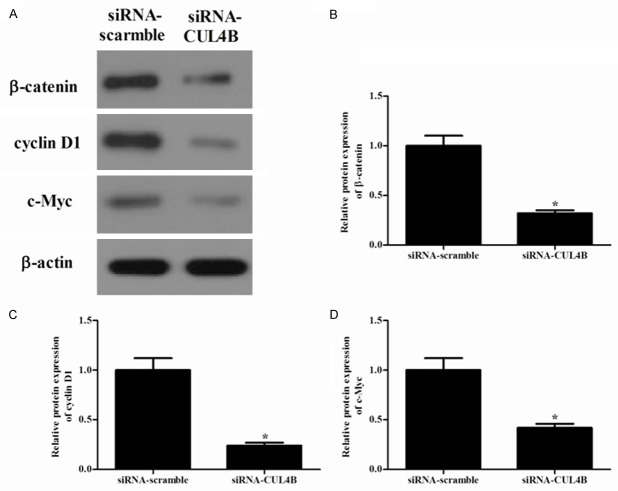

CUL4B is overexpressed in colorectal cancer cell lines

To study the expression of CUL4B in colorectal cancer, we used real-time PCR and Western blotting to determine the mRNA and protein expression of CUL4B in colorectal cancer cell lines. As shown in Figure 1A, CUL4B mRNA expression was obviously increased in colorectal cancer cell lines compared to the human colon mucosa cell line (NCM460). Consistent with the results of RT-PCR, Western blot analysis showed that CUL4B expression was higher in three colorectal cancer cell lines than the human colon mucosa cell line (Figure 1B).

Figure 1.

CUL4B is overexpressed in colorectal cancer cell lines. A. CUL4B mRNA expression was determined in several colorectal cancer cell lines and the human colon mucosa cell line. B. Western blot analysis was performed to examine CUL4B expression in colorectal cancer cell lines and the human colon mucosa cell line. β-actin was used as a loading control. *P < 0.05 versus control group. All the experiments were repeated at least three times.

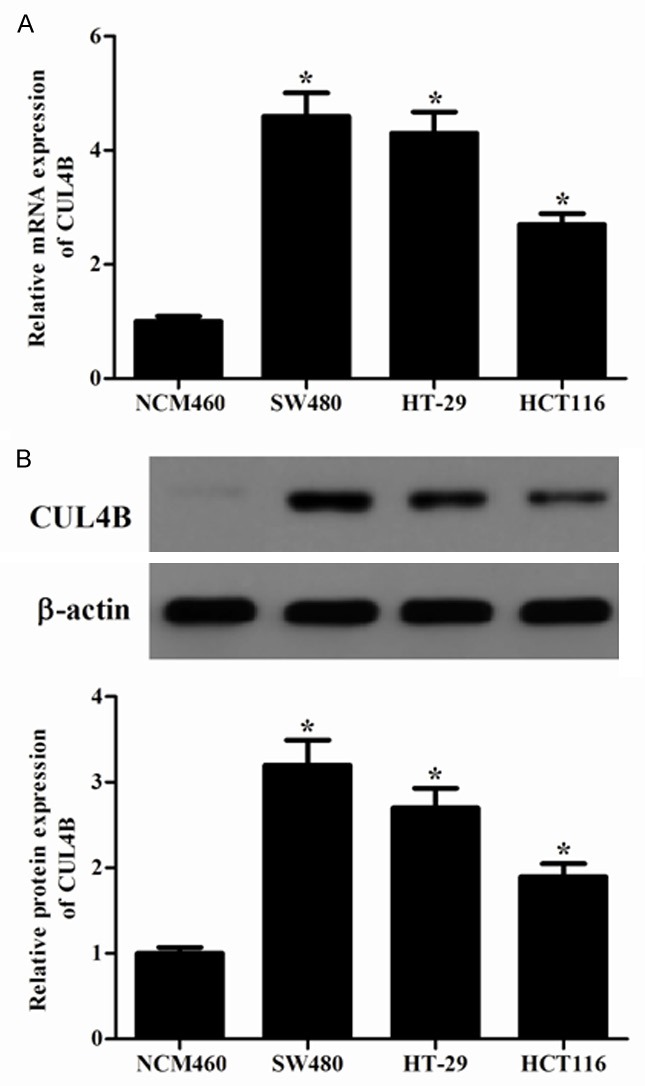

Knockdown of CUL4B inhibits the proliferation of colorectal cancer cells

To investigate the role of CUL4B in the proliferation of colorectal cancer cells, we knocked down the expression of CUL4B in SW480 and HT-29 cells using siRNA. Western blot results showed that the target sequence significantly decreased the expression of endogenous CUL4B in SW480 (Figure 2A) and HT-29 (Figure 2B) cells compared to the siRNA-scramble group. Then, we used the MTT assay to investigate the role of CUL4B in the proliferation of colorectal cancer cells. It was found that knockdown of the expression of CUL4B in SW480 cells significantly inhibited the proliferation of the cancer cells (Figure 2C). Similar results were also observed in HT-29 cells (Figure 2D).

Figure 2.

Knockdown of CUL4B expression inhibits cell proliferation in vitro. CUL4B -knockdown SW480 (A) and HT-29 (B) cells was established using siRNA. Cells transfected with empty vector served as controls. The efficacy of CUL4B knockdown was verified by western blot. Cell proliferation of siRNA-scramble control and siRNA-CUL4B SW480 (C) and HT-29 (D) cells was determined by MTT assay. *P < 0.05 versus siRNA-scramble group. All experiments were repeated at least thrice.

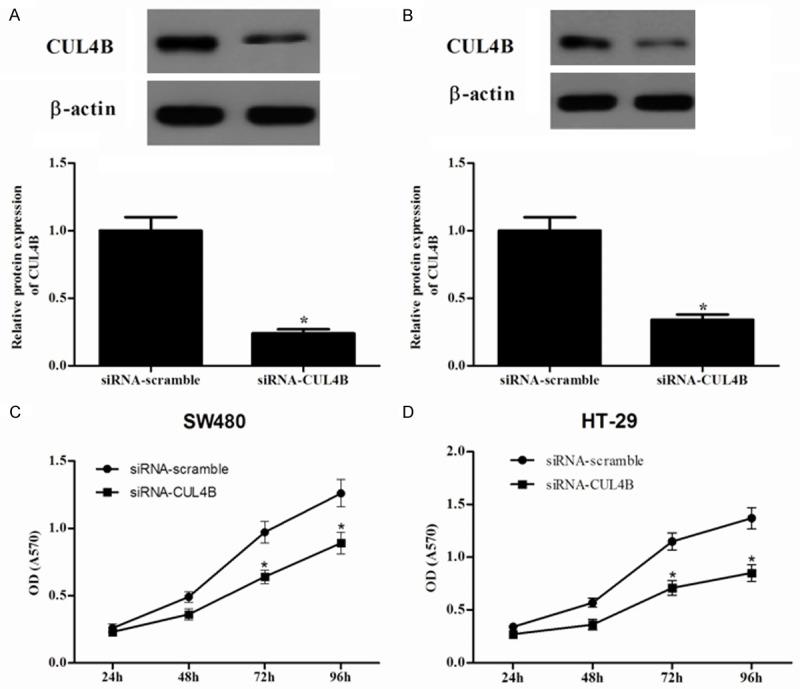

Knockdown of CUL4B promotes the apoptosis of colorectal cancer cells

To further investigate the effect of CUL4B on colorectal cancer cell apoptosis, SW480 and HT-29 cells were treated with siRNA-CUL4B and stained by flow cytometry-based Annexin V-FITC/PI double staining. As shown in Figure 3A and 3C, after treatment with siRNA-CUL4B for 24 h, the apoptosis rate of SW480 cells was 37.1%, respectively, in comparison with the control group (13.2%). Also in HT-29 cells, the proportion of apoptotic cells was higher than that of the control group (33.4% vs. 16.1%) (Figure 3B and 3C).

Figure 3.

Knockdown of CUL4B expression promotes cell apoptosis in vitro. SW480 and HT-29 cell apoptosis was detected through PI staining and the Annexin V method after 48 h of CUL4B-siRNA transfection, followed by flow cytometry. A. SW480 cells. B. HT-29 cells. C. Columns, mean data obtained from three independent experiments. *P < 0.05 versus siRNA-scramble group. All experiments were repeated at least thrice.

Knockdown of CUL4B inhibited the tumorigenicity of HT-29 cells in vivo

The role of endogenous CUL4B in the tumorigeicity of HT-29 cells was examined using a xenograft mouse model. The control cells and cells whose expression of CUL4B was knockdown were injected into the flanks of 4-week-old nude mice. The developed tumors were harvested 35 days after injection. It was found that knockdown of the expression of CUL4B retarded the tumorigenicity of HT-29 in vivo (Figure 4A), as shown by the tumor weight and tumor volume (Figure 4B and 4C). Taken together, these results suggested that down-regulation of CUL4B attenuated the tumorigenicity of the colorectal cancer cells in vivo.

Figure 4.

Knockdown of the expression of CUL4B inhibited the tumorigenicity of HT-29 cells in vivo. A. Representative images of tumor growth. B. The weight of the tumors formed by the siRNA-scramble control cells and the siRNA-CUL4B cells. C. The volume of the tumors formed by the siRNA-scramble control cells and the siRNA-CUL4B cells. *P < 0.05 versus siRNA-scramble group. All experiments were repeated at least thrice.

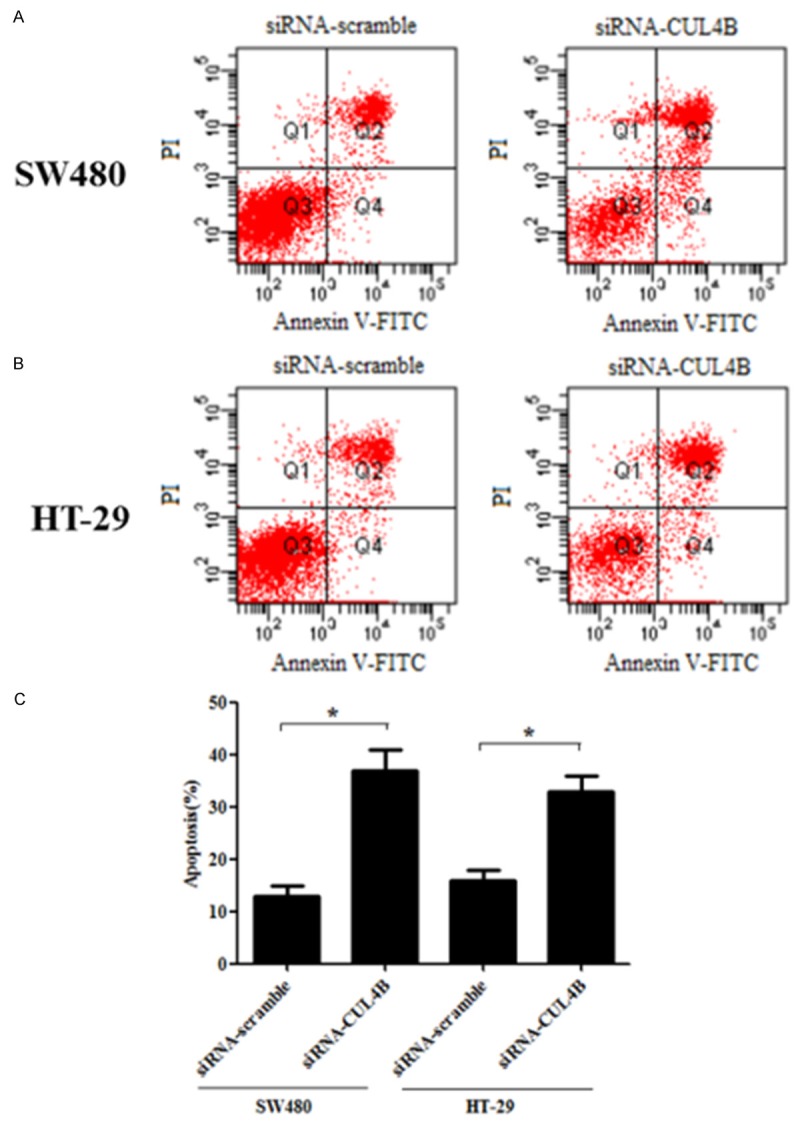

Knockdown of CUL4B promotes the apoptosis of colorectal cancer cells through Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway

The Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway is frequently upregulated in a variety of cancers, and there is some evidence showing that Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway is involved in the proliferation and apoptosis of cancer. To further investigate a potential mechanism that could be involved in the growth and migration inhibition of colorectal cancer cells, we investigated the effect of CUL4B on the expression of β-catenin, cyclin D1 and c-Myc. As shown in Figure 5, knockdown of the expression of CUL4B markedly downregulated the expression of β-catenin, cyclin D1 and c-Myc in HT-29 cells.

Figure 5.

Knockdown of CUL4B promotes the apoptosis of colorectal cancer cells through Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway. (A) The protein levels of β-catenin, cyclin D1 and c-Myc were determined by western blot analysis, β-actin was used as a loading control. (B) β-catenin, (C) Cyclin D1 and (D) c-Myc levels were quantified by Image J software and plotted relative to the control group in (A). *P < 0.05 vs. siRNA-scramble group. All the experiments were repeated at least three times.

Discussion

The key findings of this study are that CUL4B was significantly upregulated in colorectal cancer cell lines. Silencing CUL4B inhibited proliferation and tumorigenicity of colorectal cancer cells both in vitro and in vivo, and it promoted the apoptosis of colorectal cancer cells. Furthermore, knockdown of CUL4B inhibited the expression of β-catenin, cyclin D1 and c-Myc in colorectal cancer cells.

Although CUL4B has been shown to be overexpressed in several types of cancer and has been associated with cancer progression and development, its role in human colorectal cancer is still unclear. Herein, we found that CUL4B was significantly upregulated in colorectal cancer cell lines, suggesting that CUL4B may function as an oncogenic protein in the development and progression of human colorectal cancer.

Several reports have provided evidence that CUL4B is involved in the survival and proliferation of malignant phenotypes of cancer cells [7,9]. For example, knockdown of CUL4B reduced the proliferation of hepatocellular carcinoma cells in vitro and inhibited tumor growth in vivo [10]. In agreement with these reports, we found that knockdown of CUL4B inhibited proliferation and tumorigenicity of colorectal cancer cells both in vitro and in vivo [10]. Collectively, these results obtained from both in vitro and in vivo experiments strongly suggest that CUL4B overexpression plays important roles in promoting the tumorigenicity and progression of human colorectal cancer.

CUL4A is also a member of the cullin family of proteins that composes the multifunctional ubiquitin ligase E3 complex [13]. CUL4A is proposed as oncogenic based on its ability to ubiquitinate and degrade tumor suppressors, such as p21, p27, DDB2 and p53 [14,15]. Like CUL4A, CUL4B also ubiquitinates histone H2A, H3, and H4, facilitating the recruitment of repair proteins to the damaged DNA [16]. Recently, it has been shown that silencing CUL4A could promote apoptosis in human lung cancer cell lines [17]. CUL4A downregulation also induced apoptosis in human prostate cancer cells [18]. Consistent with other reports, our results showed that knockdown of CUL4B obviously promote the apoptosis of colorectal cancer cells.

Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway is considered to play a critical role in promoting tumor progression, dysregulation of cell cycle and apoptosis [19-21]. Its aberrant activation is a key event in the pathogenesis and progression of human colorectal cancers [9,22]. β-catenin is a main downstream effector of the canonical Wnt signaling pathway and accumulation of β-catenin is a hallmark of Wnt signaling activation [23]. In addition, cyclin D1 and c-Myc are downstream targets of Wnt/β-catenin signaling [24]. It has been reported that emodin significantly decreased the expression of β-catenin and that of its various downstream targets (cyclin D1, c-Myc, snail, vimentin, MMP-2 and MMP-9) in colorectal cancer cells [25]. Kaur et al showed that silibinin obviously decreased β-catenin-dependent T-cell factor-4 (TCF-4) transcriptional activity and protein expression of β-catenin target genes such as c-Myc and cyclin D1 in SW480 cells [26]. Consistent with the above data, in this study, we found that knockdown of the expression of CUL4B markedly downregulated the expression of β-catenin, cyclin D1 and c-Myc in HT-29 cells. Therefore, these results suggest that CUL4B regulates cell growth through the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway.

In conclusion, we demonstrated that knockdown of CUL4B inhibits proliferation and promotes apoptosis of colorectal cancer cells through suppressing the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway. Therefore, CUL4B may represent a novel therapeutic target for colorectal cancer treatment.

Disclosure of conflict of interest

None.

References

- 1.Siegel R, Naishadham D, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2013. CA Cancer J Clin. 2013;63:11–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Petroski MD, Deshaies RJ. Function and regulation of cullin–RING ubiquitin ligases. Nat Rev Mol Cell Bio. 2005;6:9–20. doi: 10.1038/nrm1547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bosu DR, Kipreos ET. Cullin-RING ubiquitin ligases: global regulation and activation cycles. Cell Div. 2008;3:7. doi: 10.1186/1747-1028-3-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jackson S, Xiong Y. CRL4s: the CUL4-RING E3 ubiquitin ligases. Trends Biochem Sci. 2009;34:562–570. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2009.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tarpey PS, Raymond FL, O’Meara S, Edkins S, Teague J, Butler A, Dicks E, Stevens C, Tofts C, Avis T. Mutations in CUL4B, which encodes a ubiquitin E3 ligase subunit, cause an X-linked mental retardation syndrome associated with aggressive outbursts, seizures, relative macrocephaly, central obesity, hypogonadism, pes cavus, and tremor. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;80:345–352. doi: 10.1086/511134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zou Y, Liu Q, Chen B, Zhang X, Guo C, Zhou H, Li J, Gao G, Guo Y, Yan C. Mutation in CUL4B, which encodes a member of cullin-RING ubiquitin ligase complex, causes X-linked mental retardation. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;80:561–566. doi: 10.1086/512489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hu H, Yang Y, Ji Q, Zhao W, Jiang B, Liu R, Yuan J, Liu Q, Li X, Zou Y. CRL4B catalyzes H2AK119 monoubiquitination and coordinates with PRC2 to promote tumorigenesis. Cancer Cell. 2012;22:781–795. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.10.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen Z, Shen BL, Fu QG, Wang F, Tang YX, Hou CL, Chen L. CUL4B promotes proliferation and inhibits apoptosis of human osteosarcoma cells. Oncol Rep. 2014;32:2047–2053. doi: 10.3892/or.2014.3465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yang Y, Liu R, Qiu R, Zheng Y, Huang W, Hu H, Ji Q, He H, Shang Y, Gong Y. CRL4B promotes tumorigenesis by coordinating with SUV39H1/HP1/DNMT3A in DNA methylation-based epigenetic silencing. Oncogene. 2015;34:104–118. doi: 10.1038/onc.2013.522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yuan J, Han B, Hu H, Qian Y, Liu Z, Wei Z, Liang X, Jiang B, Shao C, Gong Y. CUL4B activates Wnt/β-catenin signalling in hepatocellular carcinoma by repressing Wnt antagonists. J Pathol. 2015;235:784–795. doi: 10.1002/path.4492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jiang T, Tang HM, Wu ZH, Chen J, Lu S, Zhou CZ, Yan Dw, Peng ZH. Cullin 4B is a novel prognostic marker that correlates with colon cancer progression and pathogenesis. Med Oncol. 2013;30:534. doi: 10.1007/s12032-013-0534-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wu Z, Cui F, Yu F, Peng X, Jiang T, Chen D, Lu S, Tang H, Peng Z. Up-regulation of CHAF1A, a poor prognostic factor, facilitates cell proliferation of colon cancer. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2014;449:208–215. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2014.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee J, Zhou P. Pathogenic role of the CRL4 ubiquitin ligase in human disease. Front Oncol. 2012;2:21. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2012.00021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li B, Jia N, Kapur R, Chun KT. Cul4A targets p27 for degradation and regulates proliferation, cell cycle exit, and differentiation during erythropoiesis. Blood. 2006;107:4291–4299. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-08-3349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nag A, Bagchi S, Raychaudhuri P. Cul4A physically associates with MDM2 and participates in the proteolysis of p53. Cancer Res. 2004;64:8152–8155. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-2598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guerrero-Santoro J, Kapetanaki MG, Hsieh CL, Gorbachinsky I, Levine AS, Rapić-Otrin V. The cullin 4B-based UV-damaged DNA-binding protein ligase binds to UV-damaged chromatin and ubiquitinates histone H2A. Cancer Res. 2008;68:5014–5022. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-6162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang Y, Zhang P, Liu Z, Wang Q, Wen M, Wang Y, Yuan H, Mao JH, Wei G. CUL4A overexpression enhances lung tumor growth and sensitizes lung cancer cells to Erlotinib via transcriptional regulation of EGFR. Mol Cancer. 2014;13:252. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-13-252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ren S, Xu C, Cui Z, Yu Y, Xu W, Wang F, Lu J, Wei M, Lu X, Gao X. Oncogenic CUL4A determines the response to thalidomide treatment in prostate cancer. J Mol Med. 2012;90:1121–1132. doi: 10.1007/s00109-012-0885-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hoang BH, Kubo T, Healey JH, Yang R, Nathan SS, Kolb EA, Mazza B, Meyers PA, Gorlick R. Dickkopf 3 inhibits invasion and motility of Saos-2 osteosarcoma cells by modulating the Wnt-β-catenin pathway. Cancer Res. 2004;64:2734–2739. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.can-03-1952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang Y, Morris JP, Yan W, Schofield HK, Gurney A, Simeone DM, Millar SE, Hoey T, Hebrok M, di Magliano MP. Canonical wnt signaling is required for pancreatic carcinogenesis. Cancer Res. 2013;73:4909–4922. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-4384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shan BE, Wang MX, Li RQ. Quercetin inhibit human SW480 colon cancer growth in association with inhibition of cyclin D1 and survivin expression through Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway. Cancer Invest. 2009;27:604–612. doi: 10.1080/07357900802337191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ying J, Li H, Yu J, Ng KM, Poon FF, Wong SC, Chan AT, Sung JJ, Tao Q. WNT5A exhibits tumor-suppressive activity through antagonizing the Wnt/β-catenin signaling, and is frequently methylated in colorectal cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:55–61. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-1644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cheng XX, Wang ZC, Chen XY, Sun Y, Kong QY, Liu J, Li H. Correlation of Wnt-2 expression and β-catenin intracellular accumulation in Chinese gastric cancers: relevance with tumour dissemination. Cancer Lett. 2005;223:339–347. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2004.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tetsu O, McCormick F. β-Catenin regulates expression of cyclin D1 in colon carcinoma cells. Nature. 1999;398:422–426. doi: 10.1038/18884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pooja T, Karunagaran D. Emodin suppresses Wnt signaling in human colorectal cancer cells SW480 and SW620. Eur J Pharmacol. 2014;742:55–64. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2014.08.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kaur M, Velmurugan B, Tyagi A, Agarwal C, Singh RP, Agarwal R. Silibinin suppresses growth of human colorectal carcinoma SW480 cells in culture and xenograft through down-regulation of β-catenin-dependent signaling. Neoplasia. 2010;12:415–424. doi: 10.1593/neo.10188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]