Abstract

Background & aims: Acute pancreatitis is an inflammatory pancreatic disease that carries considerable morbidity and mortality. The pathogenesis of this disease remains poorly understood. We investigated the incidence of autophagy in mice following induction of acute pancreatitis. Methods: Mice were received intraperitoneal injections of L-arginine (200 mg × 2/100 g BW), while controls were administered with saline. Pancreatic tissues were assessed by histology, electron microscopy and western blotting. Results: Injection of L-arginine resulted in the accumulation of autophagosomes and a relative paucity of autolysosomes. Moreover, the autophagy marker p62 is significantly increased. However, the lysosomal-associated membrane protein-2 (Lamp-2), a protein that is required for the proper fusion of autophagosomes with lysosomes, is decreased in acute pancreatitis. These results suggest that a crucial role for autophagy and Lamp-2 in the pathogenesis of acute pancreatitis. Conclusions: Our data suggest that the autophagic flux is impaired in acute pancreatitis. The depletion of Lamp-2 may play a role in the pathogenesis of acute pancreatitis.

Keywords: Acute pancreatitis, autophagy, Lamp-2, p62, L-arginine

Introduction

The molecular mechanisms underlying the pathogenesis of acute pancreatitis with respect to acinar cell death have not been completely elucidated. Although the severity of experimental pancreatitis is correlated with necrosis and apoptosis [1-3], the role of autophagy in pancreatitis has not been evaluated.

Two decades ago, accumulation of autophagic vacuoles and massive acinar cell destruction (presumably due to massive necrosis) were first observed in human acute pancreatitis specimens [4]. Cytoplasmatic vacuolization is described as one of the early signs of tissue damage in pancreatitis and linked to the alteration of zymogen granules and to the formation of autophagosomes in human acute pancreatitis [4]. Recent years, evidence has accumulated that the pathological vacuolization indeed is associated with the accumulation of autophagosomes [5,6].

Lysosomal-associated membrane protein 2 (Lamp-2) is a ubiquitous lysosomal membrane protein that is highly expressed in normal human pancreatic tissue [7] and is required for the proper fusion of lysosomes with autophagosomes in the late stage of the autophagic process [8-10]. Autophagy is a dynamic, evolutionarily conserved process in which parts of the cytoplasm, including organelles and cytosolic components, are sequestered in double-membrane vesicles (autophagosomes) and then delivered to lysosomes where the autophagic cargo is degraded. The latter step involves the Lamp-2-dependent fusion of autophagosomes with lysosomes to form autophagolysosomes (also called autolysosomes) [10]. Autophagy is a cytoprotective mechanism through which cells maintain homeostatic functions such as protein and organelle turnover. It can be rapidly induced when cells require to generate intracellular nutrients and energy, for instance, upon starvation or growth factor withdrawal [10]. Lamp-2 depletion results in the inhibition of cytoprotective autophagy signaling secondary to the failure of fusion between lysosomes and autophagosomes [8,11]. A genetically determined Lamp-2 deficiency accounts for Danon disease, which is characterized by severe cardiomyopathy, myopathy, and variable mental retardation [11]. Patients with Danon disease, as well as mice deficient in Lamp-2, exhibit extensive accumulation of autophagic vacuoles in multiple cell types, including pancreatic acinar cells [8,12]. Cytoplasmatic vacuolization is also one of the early signs of cell damage in pancreatitis, although its precise mechanism remains elusive [4]. Cytoplasmatic vacuoles are linked to the alteration of zymogen granules and to the formation of autophagosomes in human acute pancreatitis [4].

The aim of the present study was to analyze autophagy in vivo by assessing ultrastructural and biochemical changes in pancreatic tissues at the early onset of acute pancreatitis. We provided evidence that the depletion of Lamp-2, strongly correlated with massive accumulation of autophagosomesand increased levels of p62 in L-arginine induced pancreatitis.

Materials and methods

Animals

Ten male KUNMING mice weighing 25 g ± 5 g were provided by the Animal Department of the Third Xiangya Hospital, Central South University. The animals were housed with free access to food and water. The room temperature was kept at 23 ± 1°C under the 12-h light/dark cycle. The institutional and licensing committee has approved the experiments undertaken. Experiments were performed in accordance with the Guidelines for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, formulated by the Ministry of Science and Technology of China.

Study design

The 10 male KUNMING mice were equally and randomly assigned to two groups: normal saline (NS) group and the experimental group. For L-arginine-induced pancreatitis, a sterile solution of L-arginine hydrochloride (20%; Sigma) was prepared in normal saline and the pH was adjusted to 7.0. Mice received two hourly intraperitoneal (i.p.) injections of L-arginine (200 mg × 2/100 g), while controls were administered saline i.p. as a control. All 10 mice were killed 24 h after intraperitoneal injections, pancreatic tissue samples were collected, snap frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at -80°C for western blotting. Formalin-fixed pancreas samples were processed, and 5 μm thick paraffin sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) for histological analysis. In addition, frozen pancreatic tissues were fixed in ice-cold 1.5% paraformaldehyde for electron microscopy observation.

Pancreatic histology

Pancreata were cut into 4-ųm-thick serial sections from 4% formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded blocks. Sections were stained with H&E and examined by a pathologist who was not aware of the sample identity. Tissue sections (n = 5) were examined for parenchymal edema, acinar cell vacuolization, necrosis, inflammatory cell infiltration, and hemorrhage and analyzed in 10 randomly selected fields with the aid of the Olympus B × 100 microscope camera system (Olympus, Hamburg, Germany). Alterations in average tissue injury were scored on the following scales.

For fibrosis: 0, no pericellular fibrosis; 1, mild pericellular fibrosis; 2, moderate pericellular intralobular fibrosis; 3, severe pericellular fibrosis. For edema: 0, no edema; 1, interlobular edema; 2, interlobular and moderate intralobular edema; 3, interlobular and severe intralobular edema. For neutrophil infiltration: 0, absent to 3, high infiltration. For necrosis: 0, no necrosis to 3, severe necrosis. For vacuoles: 0, no vacuoles to 3, maximal vacuoles.

Western blotting

The Kunming male mice were euthanized by decapitation; their pancreatic tissues were extracted in 3 min and immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen and kept at -80°C until use. Protein was extracted from the pancreatic tissue segment using the RIPA lysis buffer (Beyotime Biotech, China) following the manufacturer’s instruction. Briefly, the total protein (25 μg) was separated on SDS-polyacrylamide Gelequal (SDS-PAGE) (Beyotime Biotech, China); the proteins on the gel were transferred to a polyvinylidenedifluoride (PVDF) (Pell, USA) membrane and blocked with 5% nonfat dry milk for 1 hour. The primary antibody (1:100 dilution of rabbit polyclonalanti-Lamp-2, Abcam, Cambridge, UK) was added and incubated overnight at room temperature in fresh blocking buffer. The membrane was washed for 30 minutes in washing buffer at room temperature and incubated for 1 h with the secondary antibody conjugated with horseradish peroxidase at room temperature. The membranes were detected using ECL system (KPLBiosciences). For densitometric analysis, the band intensities were analyzed using the ImageJ software and the results were expressed as the ratio of Lamp-2 and p62 immunoreactivity to β-actin immunoreactivity.

Electron microscopy

Frozen pancreatic tissues (n = 5) were fixed in ice-cold 1.5% paraformaldehyde and embedded in Epon (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). Ultrathin sections were prepared for microscopy according to a routine procedure. Briefly, areas within scanned images of electron micrographs were measured using a Metamorph tracing semiautomatic counting tool. Each defective or intact mitochondrion was carefully outlined and the area within the traced region was determined using the analysis 3.2 Software (Soft Imaging System, Munster, Germany) in relation to the entire traced region and expressed in square nanometers. The traced region for autophagosomes and autolysosomes was determined in the same fashion. All areas were calibrated to scale bars on the micrographs and expressed as a percentage of the entire region measured and were digitally evaluated in 5 animals per group (n = 5) in 100 randomly selected 45 × 45 μm fields per animals.

Statistical analysis

All data were analyzed using SPSS version 19.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA) and expressed as mean ± SEM. Differences between groups were compared by one-way analysis of variance with group t-test. A value of P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

The model of acute pancreatitis is constructed successfully

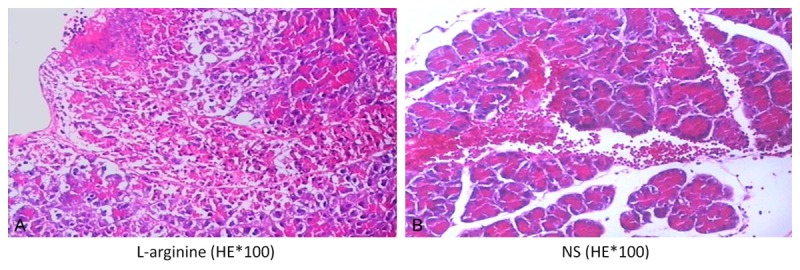

As shown in Figure 1 and Table 1. Pancreatic tissues were examined for fibrosis, parenchymal edema, inflammatory cell infiltration, acinar necrosis, and vacuolization and were analyzed in 20 randomly selected fields. Blotted are means ± SEM for 5 mice per group. H&E, 100 × original magnification. Quantitation of the average tissue vacuole assessment, *P < 0.05 vs. acute pancreatitis. Quantitation of the overall average tissue injury score, *P < 0.05 vs. acute pancreatitis.

Figure 1.

Histological assessment of pancreatic tissue in response to L-arginine (A) or saline (B). Representative tissue sections stained with H&E. Note the large area of vacuoles within this tissue.

Table 1.

Histological assessment of pancreatic tissue sections

| Group | Fibrosis | Edema | Inflammation | Necrosis | Vacuoles | Average |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NS | 0 ± 0 | 0 ± 0 | 0 ± 0 | 0 ± 0 | 0 ± 0 | 0 ± 0 |

| L-arginine | 0 ± 0 | 0.4 ± 0.1 | 0.25 ± 0.25 | 0.25 ± 0.25 | 0.75 ± 0.14* | 0.33 ± 0.15** |

Pancreatic tissues were examined for fibrosis, parenchymal edema, inflammatory cell infiltration, acinar necrosis, and vacuolization and were analyzed in 20 randomly selected fields. Blotted are means ± SEM for 5 mice per group. H&E, 100 × original magnification. Quantitation of the average tissue vacuole assessment.

P < 0.05 vs. acute pancreatitis.

Quantitation of the overall average tissue injury score;

P < 0.05 vs. acute pancreatitis.

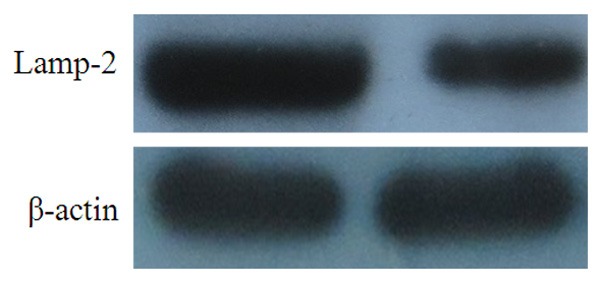

Lamp-2 depletion is involved in acute pancreatitis in response to L-arginine

As shown in Figure 2. Representative immunoblot of Lamp-2 und β-actin. The quantitation of the normalized ratio was plotted as means ± SEM of 5 animals per group. *P < 0.05 vs. acute pancreatitis. Compared with control group, the Lamp-2 protein was reduced in L-arginine induced acute pancreatitis.

Figure 2.

Representative immunoblot of Lamp-2 und β-actin. The quantitation of the normalized ratio was plotted as means ± SEM of 5 animals per group. *P < 0.05 vs. acute pancreatitis.

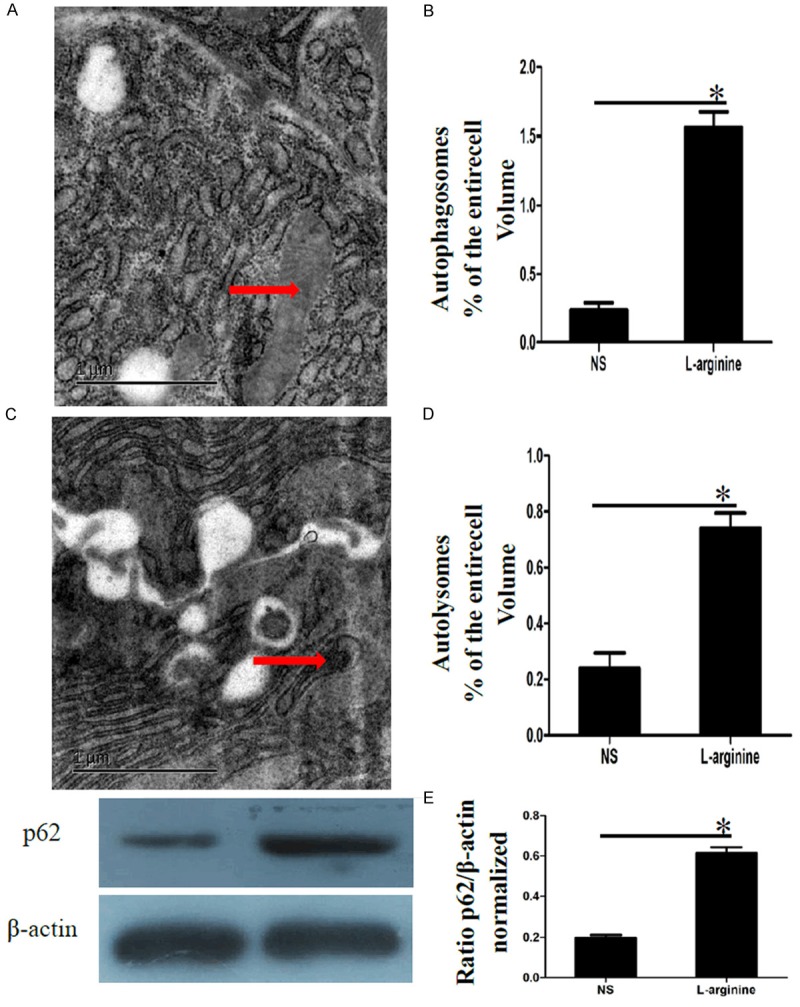

Autophagic flux is impaired in L-arginine induced acute pancreatitis

As shown in Figure 3. Electron microscopy assessment of autophagosomal and autolysosomal formation. A: Representative EM image of pancreatic acinar cells. The red arrow indicates a typical autophagosomes containing mitochondria and other intracellular components. B: Quantitation of autophagosomes of the entire acinar cell volume (determined as a percentage as in A. Plotted as means ± SEM of 5 individuals per group. *P < 0.05 vs. acute pancreatitis. C: Representative EM image of pancreatic acinar cells. The red arrow indicates a typical autolysosomes containing digested mitochondria and other intracellular components. D: Quantitation of the volume of autolysosomes (expressed as percentage of the total acinar cell volume). Plotted as means ± SEM of 5 animals per group. *P < 0.05 vs. acute pancreatitis. E: Representative immunoblot of p62 und β-actin. The quantitation of the normalized ratio was plotted as means ± SEM of 5 animals per group. *P < 0.05 vs. acute pancreatitis. Compared with control group, the p62 protein was significantly up-regulated in L-arginine induced acute pancreatitis.

Figure 3.

Electron microscopy assessment of autophagosomal and autolysosomal formation. A: Representative EM image of pancreatic acinar cells. The red arrow indicates a typical autophagosomes containing mitochondria and other intracellular components. B: Quantitation of autophagosomes of the entire acinar cell volume (determined as a percentage as in A. Plotted as means ± SEM of 5 individuals per group. *P < 0.05 vs. acute pancreatitis. C: Representative EM image of pancreatic acinar cells. The red arrow indicates a typical autolysosomes containing digested mitochondria and other intracellular components. D: Quantitation of the volume of autolysosomes (expressed as percentage of the total acinar cell volume). Plotted as means ± SEM of 5 animals per group. *P < 0.05 vs. acute pancreatitis. E: Representative immunoblot of p62 und β-actin. The quantitation of the normalized ratio was plotted as means ± SEM of 5 animals per group. *P < 0.05 vs. acute pancreatitis.

Discussion

Our results demonstrate that following injection of L-arginine results in a depletion of Lamp-2. It is conceivable that inhibition of cytoprotective autophagy induction occurs as a result of the failure of autophagosomal and lysosomal fusion. Lysosomal-associated membrane protein 2 (Lamp-2) is a ubiquitous lysosomal membrane protein that is highly expressed in normal human pancreatic tissue [7] and is required for the proper fusion of lysosomes with autophagosomes in the late stage of the autophagic process [8,10]. In addition, knockout or knockdown of Lamp-2 is used as an experimental strategy for the inhibition of autophagosome-lysosome fusion and triggers the accumulation of autophagosomes by blocking their turnover [13,14]. Thus, the depletion of Lamp-2 protein which is induced by L-arginine may explain the perturbation of autophagy in pancreatitis.

Our results demonstrate that the autophagy marker p62 is significantly increased after following injection of L-arginine. This is consistent with the massive formation of autophagosomes and reduction of autolysosomes. Of note, the number of autophagosomes observed at any time reflexes the balance between the rates of their generation and degradation during the subsequent stages of autophagy. The p62 is localized at the autophagosome formation site [15] and directly interacts with LC3, an autophagosome location protein [16-19]. In this context, the p62 is incorporated into the autophagosome and then degraded. Taken together, the massive formation of autophagosomes and reduction of autolysosomes and increased levels of p62 reveal that autophagic flux is impaired in pancreatitis.

Our study provided evidence that autophagic flux is impaired in experimental pancreatitis, the depletion of Lamp-2 plays a critical role in the early onset of acute pancreatitis. Irrespective of its precise molecular mechanisms, it appears thatLamp-2 depletion may serve as a biomarker for further investigations of the pathogenesis of acute pancreatitis. In addition, impaired autophagy may be also important in the pathogenesis of chronic pancreatitis, particularly in pancreatic fibrosis, which merits further investigation. For example, fibrosis might be initiated if autophagic removal of ubiquitinated protein aggregates is impaired (due to defective clearance of p62), as was shown in a mouse model of the liver disease α1-antitrypsin deficiency [20]. In addition, autophagy may also regulate the activation of satellite cells in pancreatitis [21].

Acknowledgements

The project was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 81270545). The project was supported by the Science and Technology Department of Hunan Province Foundation of China (Grant No. 2013FJ6021). The project was supported by the Hunan Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 12JJ5052). The project was supported by the Changsha City Science Foundation of China (Grant No. k1207032-31-1).

Disclosure of conflict of interest

None.

References

- 1.Mareninova OA, Sung KF, Hong P, Luqea A, Pandol SJ, Gukovsky I, Gukovskaya AS. Cell death in pancreatitis: caspases protect from necrotizing pancreatitis. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:3370–3381. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M511276200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gukovskaya AS, Mareninova OA, Odinokova IV, Sung KF, Luqea A, Fischer L, Wang YL, Gukovsky I, Pandol SJ. Cell death in pancreatitis: effects of alcohol. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;21:S10–S13. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2006.04571.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fortunato F, Deng X, Gates LK, McClain CJ, Bimmler D, Graf R, Whitcomb DC. Pancreatic response to endotoxin after chronic alcohol exposure: switch from apoptosis to necrosis? Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2006;290:G232–G241. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00040.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Helin H, Mero M, Markkula H, Helin M. Pancreatic acinar ultrastructure in human acute pancreatitis. Virchows Arch A Pathol Anat Histol. 1980;387:259–70. doi: 10.1007/BF00454829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hashimoto D, Ohmuraya M, Hirota M, Yamamoto A, Suyama K, Ida S, Okumura Y, Takahashi E, Kido H, Araki K, Baba H, Mizushima N, Yamamura K. Involvement of autophagy in trypsinogen activation within the pancreatic acinar cells. J Cell Biol. 2008;181:1065–72. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200712156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ohmuraya M, Yamamura KI. Autophagy and acute pancreatitis: A novel autophagy theory for trypsinogen activation. Autophagy. 2008;4:1060–62. doi: 10.4161/auto.6825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Furuta K, Yang XL, Chen JS, Hamilton SR, Auqust JT. Differential expression of the lysosome-associated membrane proteins in normal human tissues. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1999;365:75–82. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1999.1147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eskelinen EL, Illert AL, Tanaka Y, Schwarzmann G, Blanz J, Von Fiqura K, Saftig P. Role of LAMP-2 in lysosomebiogenesis and autophagy. Mol Biol Cell. 2002;13:3355–3368. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E02-02-0114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huynh KK, Eskelinen EL, Scott CC, Malevanets A, Saftiq P, Grinstein S. LAMP proteins are required for fusion of lysosomes with phagosomes. EMBO J. 2007;26:313–324. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Levine B, Kroemer G. Autophagy in the pathogenesis of disease. Cell. 2008;132:27–42. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.12.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Saftig P, Tanaka Y, Lullmann-Rauch R, von Figura K. Disease model: LAMP-2 enlightens Danon disease. Trends Mol Med. 2001;7:37–39. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4914(00)01868-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tanaka Y, Guhde G, Suter A, Eskelinen EL, Hartmann D, Lullmann-Rauch R, Janssen PM, Blanz J, von Figura K, Saftig P. Accumulation of autophagic vacuoles and cardiomyopathy in LAMP-2-deficient mice. Nature. 2000;406:902–906. doi: 10.1038/35022595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Boya P, Gonzalez-Polo RA, Casares N, Perfettini JL, Dessen P, Larochette N, Métivier D, Meley D, Souquere S, Yoshimori T, Pierron G, Codogno P, Kroemer G. Inhibition of macroautophagy triggers apoptosis. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:1025–40. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.3.1025-1040.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gonzalez-Polo RA, Boya P, Pauleau AL, Jalil A, Larochette N, Souquere S, Eskelinen EL, Pierron G, Saftig P, Kroemer G. The apoptosis/autophagy paradox: autophagic vacuolization before apoptotic death. J Cell Sci. 2005;118:3091–3102. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Itakura E, Mizushima N. p62 targeting to the autophagosome formation site requires self-oligomerization but not LC3 binding. J Cell Biol. 2011;192:17–27. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201009067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ichimura Y, Kumanomidou T, Sou YS, Mizushima T, Ezaki J, Ueno T, Kominami E, Yamane T, Tanaka K, Komatsu M. Structural basis for sorting mechanism of p62 in selective autophagy. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:22847–22857. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M802182200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Noda NN, Kumeta H, Nakatogawa H, Satoo K, Adachi W, Ishii J, Fujioka Y, Ohsumi Y, Inagaki F. Structural basis of target recognition by Atg8/LC3 during selective autophagy. Genes Cells. 2008;13:1211–1218. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2443.2008.01238.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pankiv S, Clausen TH, Lamar kT, Brech A, Outzen H, Overvatn A, Bjørkøy G, Johansen T. p62/SQSTM1 binds directly to Atg8/LC3 to facilitate degradation of ubiquitinated protein aggregates by autophagy. J Biol Chem. 2010;282:24131–24145. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M702824200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shvets E, Fass E, Scherz-Shouval R, Elazar Z. The N-terminus and Phe52 residue of LC3 recruit p62/SQSTM1 into autophagosomes. J Cell Sci. 2008;121:2685–2695. doi: 10.1242/jcs.026005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hidvegi T, Ewing M, Hale P, Dippold C, Beckett C, Kemp C, Maurice N, Mukherjee A, Goldbach C, Watkins S, Michalopoulos G, Perlmutter DH. An autophagy enhancing drug promotes degradation of mutant alpha1-antitrypsin Z and reduces hepatic fibrosis. Science. 2010;329:229–232. doi: 10.1126/science.1190354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rickmann M, Vaquero EC, Malaqelada JR, Molero X. Tocotrienols induce apoptosis and autophagy in rat pancreatic stellate cells through the mitochondrial death pathway. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:2518–2532. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.03.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]