Abstract

Homeobox protein Hox-D13 has been recognized as a tumor suppressor in pancreatic cancer. To evaluate the function of HOXD13 in invasive breast cancer pathogenesis, we examined HOXD13 expression in 434 breast cancer tissues and 230 their counterpart normal breast tissues by immunohistochemistry using a tissue microarray (TMA). The association between HOXD13 expression and clinicopathological factors was analyzed by use of Chi-square test. Kaplan-Meier survival curves and log-rank tests were applied to analyze the survival status. Cox regression was applied for multivariate analysis of prognosis. We found that low HOXD13 expression accounts for 84.3% in breast cancer tissues. Low HOXD13 expression was significantly associated with large tumor size (P=0.038) and positive lymph node metastasis (LNM) (P=0.026). In Kaplan-Meier survival curves and log-rank tests, the patients with HOXD13-negative breast cancer showed significantly poorer outcomes (69.867 ± 1.058 months) in terms of overall survival (OS) than positive-HOXD13-expression patients (76.248 ± 1.069 months) (P=0.003). And in multivariate analysis, low level of HOXD13 expression was a significant unfavorable prognostic factor. So we conclude that down-regulation of HOXD13 might be a potentially useful prognostic marker for patients with breast cancer.

Keywords: HOXD13, breast cancer, prognosis, tissue microarray

Introduction

Breast cancer is one of the most common tumors in human and it is responsible for approximately 29% of new cancer cases and 15% of total cancer-related death in the United States [1]. Recognizing the genes in charge of the onset and evolution of breast cancer and identifying their clinical value are crucial to the diagnosis and therapy of the disease.

In mammals, such as mice (Hox genes) and humans (HOX genes), 39 HOX genes are separated into four independent groups, namely, HOX A, B, C and D, which are localized at 7p15.3, 17p21.3, 12q13.3 and 2q31, respectively [2]. HOX genes are crucial for development, and any abnormal expression during the developmental procedure may lead to dysplasia [3]. Moreover, numerous HOX genes have been discovered to be abnormally expressed in different forms of cancers, thus indicating that HOX genes may serve a function in oncogenesis or tumor suppression [4-7].

HOXD13, the mutation of which may be associated with synpolydactyly [8], is the 13th paralogous member of the HOXD gene family [9]. Abnormal HOXD13 expression was observed in different tumor forms, such as cutaneous malignant melanoma [10] and cervical carcinoma [11]. These studies indicated that HOXD13 may serve a critical function in tumor progression.

To investigate the relationship between HOXD13 expression and the clinic-pathological features of patients with breast cancer, we used a tissue microarray (TMA) which contains 434 breast cancer samples and their 230 normal counterpart tissues. To the best of knowledge, this study has the most number of samples used to evaluate the HOXD13 expression in immunohistochemical staining by TMA. Furthermore, this study has significant contribution to the evaluation of the relationship tween HOXD13 expression and patient survival in breast cancer.

Materials and methods

Patients and tissue specimens

A total of 434 paraffin-embedded samples of invasive breast ductal carcinomas and 230 corresponding normal breast tissues were obtained from the Department of Pathology of the Affiliated Tumor Hospital of Harbin Medical University. Informed consent was obtained from the subjects, and the study was performed with the approval of the Ethical Committee of Harbin Medical University. The patients had complete medical records since 2006. Clinical records were obtained from the department providing follow-up cares. The patients were all female. The median age of the patients was 48 years (range 28-76 years). Patients were followed up for at least 3 months and up to 82 months (median 74 months). All patients had a definite pathological diagnosis, and none received any therapy before surgery. Each sample was routinely tested for estrogen receptor (ER), progesterone receptor (PR), human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2), Ki-67 and p53 with immunohistochemistry. Immunohistochemical markers were assayed in paraffin-embedded, formalin-fixed tissue stained with hematoxylin and eosin using antibodies to the proteins ER, PR, Her-2, Ki-67 and p53 (Zhong shan-Bio Co., Beijing, China). Samples that had nuclear staining for ER or PR in more than 1% of the cells were considered ER-positive or PR-positive, respectively [12]. Positive staining for HER2 was defined on the basis of the percentage of tumor cells and the intensity of membrane staining. HER2 was scored from 0 to 3+ based on the method recommended for the DakoHercepTest. Tumors were recognized as positive for HER2 if immunostaining was scored as 3+ or when the HER-2 fluorescence in situ hybridization (GP medical technologies Co Ltd. Beijing, China) amplification ratio was greater than 2.2 [13]. Ki-67 and p53 staining cells were counted and expressed as a percentage. Low expression was identified as Ki-67<14% [14] and p53<25% [15].

Follow-up

The clinical records were obtained from the departments providing follow-up care. Patients were followed up regularly for at least 3 months and up to 82 months (median 74 months). Overall survival (OS) time was defined as the time interval from the date of surgery to the date of death, which was the assessment used for prognostic analyses.

Tumor phenotype classification

According to the Scarff-Bloom-Richardson system, the invasiveness of cancers can be determined on the basis of the extent of cell mitosis frequency, tubule formation, and nuclear pleomorphism. Invasiveness in patients was classified as low grade (grade I), moderate grade (grade II) and high grade (grade III). Grades I and II were grouped together. The occurrence of lymph node metastases (LNM) and tumor size (negative: <2 cm; positive: ≥2 cm) were also recorded for each patient.

Molecular subtypes of breast cancer were assified according to St. Gallen International Breast Cancer Conference 2011 criteria [16]: Luminal A type: ER and/or PR-positive and HER2-negative and Ki-67 low (<14%); Luminal B type: (HER2-negative) ER and/or PR positive and HER2 negative and Ki-67 high (≥14%); (HER2 positive) ER and/or PR positive and HER2 overexpressed or amplified and any Ki67; HER2 positive type: ER and PR negative and HER2-overexpressed or amplified; and Triple- negative breast cancer (TNBC) type: ER-, PR-, and HER2-negative.

Tissue microarray construction

Using a punch machine, the selected area of paraffin block was punched out, and a 3- mm tissue core was placed onto a recipient block. The selected tissue was then extracted. More than two tissue cores were extracted to minimize extraction bias. All breast invasive ductal carcinomas and corresponding normal breast sample blocks were cut with a microtome to 4 μm and arrayed as triplicate. Each tissue core was assigned a unique TMA location number linked to a database containing other clinic-pathological data.

Immunohistochemistry

The tissue sections were dried at 70°C for 3 hours. After deparaffinization and hydration, the tissue sections were washed in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; 3×3 min). The washed sections were treated with 3% H2O2 in the dark for 5 min to 20 min. After washing with distilled water, sections were washed with PBS (3×5 min). Antigen retrieval was performed in citrate buffer (pH 6.0). Each section was then treated with 300 ml to 500 ml of HOXD13 rabbit polyclonal antibodies (Abcam, Cambridge, MA at a dilution of 1:300) solution at 4°C overnight. After washing with PBS (3×5 min), each section was incubated with 300 ml to 500 ml of secondary antibody at room temperature for 30min. After washing with PBS (3×5 min), each section was treated with 300 ml to 500 ml of diaminobenzadine (DAB) working solution at room temperature for 3 min to 10 min, and then washed with distilled water.

Evaluation of HOXD13 protein expression

HOXD13 protein expression was assessed by evaluating the proportion and intensity of staining, which was considered as a representation of the average in a 400× magnification field. Briefly, the proportion of positively stained tumor cells in a field was scored as follows: 0: none; 1: <10%; 2:10% to 50% and 3: >50%. The staining intensity in a field was scored as follows: 0: no staining; 1: weak staining, appearing as light yellow; 2: moderate staining, appearing as yellowish-brown and 3: strong staining, appearing as brown. The staining index (SI) was calculated as: (averaged staining intensity score) × (proportion score). An SI score of 4 (a cut-off point) was used to distinguish between low (≤4) and high (>4) expression of HOXD13 [17]. The staining on each sample was scored independently by two pathologists without knowledge of the clinic-pathological findings.

Statistical analysis

Data were processed using SAS software (version 9.1.3; SAS Institute, North Carolina, USA). The chi-square test was used to examine any differences in categorical variables. Kaplan Meier survival curves and log-rank statistics were employed to evaluate the association of HOXD13 expression and death using OS. The influence of different variables on survival was assessed using Cox univariate and multivariate regression analyses. Hazard ratios and their 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were recorded for each marker. Significance was assumed when P<0.05.

Results

Decreased HOXD13 expression is common in breast cancer tissue

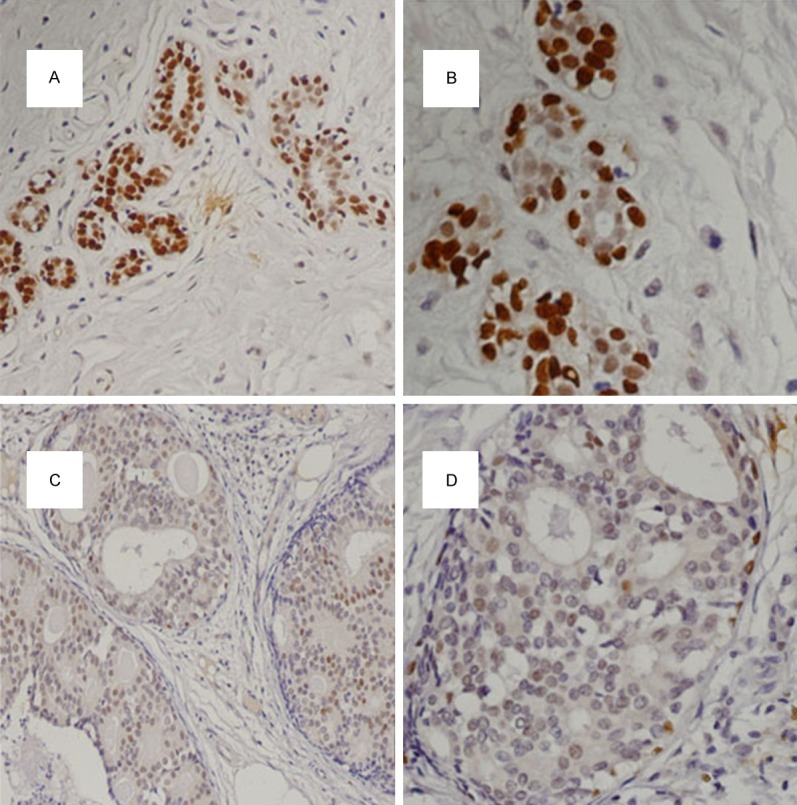

To evaluate HOXD13 expression levels in breast cancer tissues and matched normal breast tissues, breast TMA was utilized. Immunostaining with HOXD13 protein specific antibody exhibited two patterns: nuclear staining and cytoplasmic staining. However, according to the prior research [18], cytoplasmic staining was disregarded in this work. In this study, HOXD13 protein decreased expression was common in the tumor cells (Figure 1). The rate of low- HOXD13- expression accounts for approximately 84.3% in cancer tissues in this experiment.

Figure 1.

Immunohistochemical staining of HOXD13 protein in breast tissues. High expression in normal breast tissue (200×). High expression in normal breast tissue (400×). Low expression in breast cancer tissue (200×). Low expression in breast cancer tissue (400×).

Decreased HOXD13 protein expression correlates with large tumor size and positive lymph node metastasis

We also analyzed the correlation between HOXD13 expression level and various clinic-pathological characteristics (Table 1). We discovered that decreased HOXD13 expression was significantly associated with large tumor size (P=0.038) and positive LNM (P=0.026). In HOXD13 low expression group, the rate of large tumor size is more than small tumor size. And in HOXD13 low expression group, the ratio of positive LNM is larger than negative LNM. However, no difference between HOXD13 expression and other clinic-pathological characteristics was found.

Table 1.

Association between HOXD13 expression and clinic-pathological features

| Variations | Samples | HOXD13 low expression | HOXD13 high expression | x 2 | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 1.600 | 0.206 | |||

| <50 | 241 | 208 (86.3%) | 33 (13.7%) | ||

| ≥50 | 193 | 158 (81.9%) | 35 (18.1%) | ||

| Grade | |||||

| Grade I, II | 150 | 123 (82.0%) | 27 (18.0%) | 0.943 | 0.331 |

| Grade III | 284 | 243 (85.6%) | 41 (14.4%) | ||

| Tumor size (cm) | 4.307 | 0.038* | |||

| <2 | 82 | 63 (76.8%) | 19 (23.2%) | ||

| ≥2 | 352 | 303 (86.1%) | 49 (13.9%) | ||

| LNM | 4.947 | 0.026* | |||

| Negative | 209 | 168 (80.4%) | 41 (19.6%) | ||

| Positive | 220 | 194 (88.2%) | 26 (11.8%) | ||

| TNM stage | 4.605 | 0.100 | |||

| I | 84 | 66 (78.6%) | 18 (21.4%) | ||

| II | 208 | 174 (83.7%) | 34 (16.3%) | ||

| III | 138 | 123 (89.1%) | 15 (10.9%) | ||

| ER | 2.786 | 0.095 | |||

| Negative | 238 | 207 (87.0%) | 31 (13.0%) | ||

| Positive | 196 | 159 (81.1%) | 37 (18.9%) | ||

| PR | 0.147 | 0.702 | |||

| Negative | 176 | 147 (83.5%) | 29 (16.5%) | ||

| Positive | 258 | 219 (84.9%) | 39 (15.1%) | ||

| HER2 | 0.079 | 0.779 | |||

| Negative | 255 | 214 (83.9%) | 41 (16.1%) | ||

| Positive | 179 | 152 (84.9%) | 27 (15.1%) | ||

| p53 | 0.043 | 0.836 | |||

| Negative | 212 | 178 (84.0%) | 34 (16%) | ||

| Positive | 222 | 188 (84.7%) | 34 (15.3%) | ||

| Ki67 | 1.854 | 0.173 | |||

| Negative | 237 | 205 (86.5%) | 32 (13.5%) | ||

| Positive | 197 | 161 (81.7%) | 36 (18.3%) | ||

| Molecular subtype | 0.109 | 0.991 | |||

| Luminal A | 165 | 138 (83.6%) | 27 (16.4%) | ||

| Luminal B | 120 | 102 (85.0%) | 18 (15.0%) | ||

| HER2 | 59 | 50 (84.7%) | 9 (15.3%) | ||

| Triple negative | 90 | 76 (84.4%) | 14 (15.6%) |

P<0.05.

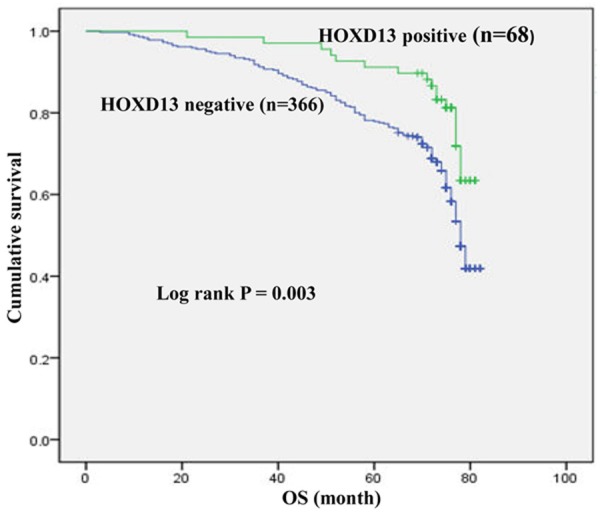

Low HOXD13 expression correlates with poor patients’ survival

To study whether HOXD13 expression is associated with 5-year overall survival (OS), we utilized Kaplan-Meier survival analysis and log-rank test. Kaplan Meier survival curves are shown in Figure 2. Among the 434 patients, the negative-HOXD13-expression patients showed significantly poorer outcomes (69.867±1.058 months) in terms of overall survival (OS) than positive-HOXD13-expression patients (76.248±1.069 months) (P=0.003).

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier curves for HOXD13 expression in relation with overall survival in 434 breast cancers. Patients with low HOXD13 expression had a significantly worse prognosis than those with high HOXD13 expression (P=0.003, log-rank test).

Both univariate and multivariate survival analyses were utilized to assess the relationship of HOXD13 expression and clinic-pathological features on prognosis. Using Cox regression analysis, univariate analyses of OS showed that HOXD13 expression (P=0.004), grade (P=0.019), LNM (P<0.001), ER (P<0.001), PR (P=0.001), Ki67 (P<0.001) and TNM (P<0.001) as significant prognostic factors. We discovered no other features had merits of prognosis. By use of a Cox regression model, multivariate analysis was utilized on the same set of patients for HOXD13 expression and for pathological factors of survival time. Using multivariate analysis, we discovered that HOXD13 expression (P=0.029), TNM stage (P<0.001), ER status (P=0.004) and Ki67 (P=0.01) were independent prognostic predictors. Given that HR<1 in HOXD13 expression and ER, so low HOXD13 expression and negative ER showed a higher risk of death. When TNM and Ki67 HR>1, higher stage and enhanced Ki67 proliferation induced a higher risk of death (Table 2).

Table 2.

Univariate and multivariate Cox regression analysis

| Variables | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| HR | 95% CI | P | HR | 95% CI | P | |

| Age (≥50 vs. <50) | 1.003 | (0.750, 1.342) | 0.982 | |||

| Grade (III vs. II+I) | 1.478 | (1.068, 2.045) | 0.019* | |||

| Tumor size (≥2 cm vs. <2 cm) | 1.025 | (0.700, 1.502) | 0.899 | |||

| LNM (Positive vs. Negative) | 2.558 | (1.866, 3.508) | <0.001* | |||

| ER (Positive vs. Negative) | 0.575 | (0.424, 0.780) | <0.001* | 0.631 | (0.461, 0.864) | 0.004* |

| PR (Positive vs. Negative) | 0.599 | (0.448, 0.800) | 0.001* | |||

| Her2 (Positive vs. Negative) | 0.943 | (0.701, 1.268) | 0.696 | |||

| P53 (Positive vs. Negative) | 1.177 | (0.881, 1.573) | 0.271 | |||

| Ki-67 (Positive vs. Negative) | 1.685 | (1.259, 2.255) | <0.001* | 1.484 | (1.099, 2.005) | 0.01* |

| TNM stage (III vs. II+I) | 3.535 | (2.635, 4.741) | <0.001* | 3.260 | (2.421, 4.389) | <0.001* |

| HOXD13 expression (high vs. low) | 0.476 | (0.289, 0.784) | 0.004* | 0.571 | (0.345, 0.945) | 0.029* |

P<0.05.

Discussion

The breast cancer is the most common tumor in female [1]. Although much has been studied about its molecular pathology and pivotal progress has been achieved in its prevention as well as therapy, it still remains one of the major public health problems of the female population. New biomarkers of prognosis for breast cancer should be detected.

A variety of HOX genes were found to be expressed at a lower level in breast cancer tissues than normal breast tissues [19]. Aberrant expression of HOXD13 has been reported in different tumor types [10,11,18,19]. Low HOXD13 expression is common in pancreatic tumors and may be a marker of poor prognosis [18]. In our study, of the 434 breast cancer patients, 366 were HOXD13-negative low expression of HOXD13 (accounts for approximately 84.3%). HOXD13 expression in the nucleus of cancer cells is associated with large tumor size (P=0.038) and positive LNM (P=0.026). It indicated that HOXD13 expression may play a role in tumor progression. We also found that patients with low levels of HOXD13 expression had significantly poorer OS rates than patients with high HOXD13 expression (Figure 2). HOXD13 expression is an independent unfavorable survival factor for patients with invasive breast cancer.

In our study, we also evaluated the association between HOXD13 expression and various clinic-pathological factors. The rate of negative HOXD13 in the large tumor group is significantly higher than that in the small tumor group (86.1 and 76.8%, respectively) (P=0.038). And in HOXD13 low expression, the rate of positive LNM is larger than that in negative LNM group. So we speculated that low expression of HOXD13 may take a role in breast cancer progression. However, we did not exactly know how HOXD13 worked. So in next step, we should do mechanism studies in breast cancer.

In conclusion, our study showed that HOXD13 is associated with large tumor size and positive LNM in breast cancer. Low level of HOXD13 protein correlated with poorer survival in patients with breast cancer. Our results suggest that HOXD13 may serve as a tumor suppressor gene in breast cancer and that HOXD13 may be a potential new drug target in breast cancer treatment.

Acknowledgements

This project is supported by grants from National Natural Science Fund (No. 81172498), the funding of The Affiliated Tumour Hospital of Harbin Medical University (No. JJZ2010-04), the ‘Wu Liande’ funding of Harbin Medical University (No. WLD-QN1118) and the Special Fund of Translational Medical Research between China and Russia (No. CR201402).

Disclosure of conflict of interest

None.

References

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2015. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015;65:5–29. doi: 10.3322/caac.21254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Apiou F, Flagiello D, Cillo C, Malfoy B, Poupon MF, Dutrillaux B. Fine mapping of human HOX gene clusters. Cytogenet Cell Genet. 1996;73:114–115. doi: 10.1159/000134320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goodman FR. Congenital abnormalities of body patterning: embryology revisited. Lancet. 2003;362:651–662. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14187-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Henderson GS, van Diest PJ, Burger H, Russo J, Raman V. Expression pattern of a homeotic gene, HOXA5, in normal breast and in breast tumors. Cell Oncol. 2006;28:305–313. doi: 10.1155/2006/974810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Raman V, Martensen SA, Reisman D, Evron E, Odenwald WF, Jaffee E, Marks J, Sukumar S. Compromised HOXA5 function can limit p53 expression in human breast tumours. Nature. 2000;405:974–978. doi: 10.1038/35016125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Svingen T, Tonissen KF. Altered HOX gene expression in human skin and breast cancer cells. Cancer Biol Ther. 2003;2:518–523. doi: 10.4161/cbt.2.5.441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wu X, Chen H, Parker B, Rubin E, Zhu T, Lee JS, Argani P, Sukumar S. HOXB7, a homeodomain protein, is overexpressed in breast cancer and confers epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Cancer Res. 2006;66:9527–9534. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-4470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Muragaki Y, Mundlos S, Upton J, Olsen BR. Altered growth and branching patterns in synpolydactyly caused by mutations in HOXD13. Science. 1996;272:548–551. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5261.548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Scott MP. Vertebrate homeobox gene nomenclature. Cell. 1992;71:551–553. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90588-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Maeda K, Hamada J, Takahashi Y, Tada M, Yamamoto Y, Sugihara T, Moriuchi T. Altered expressions of HOX genes in human cutaneous malignant melanoma. Int J Cancer. 2005;114:436–441. doi: 10.1002/ijc.20706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hung YC, Ueda M, Terai Y, Kumagai K, Ueki K, Kanda K, Yamaguchi H, Akise D, Ueki M. Homeobox gene expression and mutation in cervical carcinoma cells. Cancer Sci. 2003;94:437–441. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2003.tb01461.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hammond ME, Hayes DF, Dowsett M, Allred DC, Hagerty KL, Badve S, Fitzgibbons PL, Francis G, Goldstein NS, Hayes M, Hicks DG, Lester S, Love R, Mangu PB, McShane L, Miller K, Osborne CK, Paik S, Perlmutter J, Rhodes A, Sasano H, Schwartz JN, Sweep FC, Taube S, Torlakovic EE, Valenstein P, Viale G, Visscher D, Wheeler T, Williams RB, Wittliff JL, Wolff AC. American Society of Clinical Oncology/College of American Pathologists guideline recommendations for immunohistochemical testing of estrogen and progesterone receptors in breast cancer. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2010;134:907–922. doi: 10.5858/134.6.907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wolff AC, Hammond ME, Schwartz JN, Hagerty KL, Allred DC, Cote RJ, Dowsett M, Fitzgibbons PL, Hanna WM, Langer A, McShane LM, Paik S, Pegram MD, Perez EA, Press MF, Rhodes A, Sturgeon C, Taube SE, Tubbs R, Vance GH, van de Vijver M, Wheeler TM, Hayes DF. American Society of Clinical Oncology/College of American Pathologists guideline recommendations for human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 testing in breast cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2007;25:118–145. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.09.2775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cheang MC, Chia SK, Voduc D, Gao D, Leung S, Snider J, Watson M, Davies S, Bernard PS, Parker JS, Perou CM, Ellis MJ, Nielsen TO. Ki67 index, HER2 status, and prognosis of patients with luminal B breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2009;101:736–750. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djp082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jung SY, Kim HY, Nam BH, Min SY, Lee SJ, Park C, Kwon Y, Kim EA, Ko KL, Shin KH, Lee KS, Park IH, Lee S, Kim SW, Kang HS, Ro J. Worse prognosis of metaplastic breast cancer patients than other patients with triple-negative breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2010;120:627–637. doi: 10.1007/s10549-010-0780-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goldhirsch A, Wood WC, Coates AS, Gelber RD, Thurlimann B, Senn HJ. Strategies for subtypes--dealing with the diversity of breast cancer: highlights of the St. Gallen International Expert Consensus on the Primary Therapy of Early Breast Cancer 2011. Ann Oncol. 2011;22:1736–1747. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdr304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liu T, Zhang X, Shang M, Zhang Y, Xia B, Niu M, Liu Y, Pang D. Dysregulated expression of Slug, vimentin, and E-cadherin correlates with poor clinical outcome in patients with basal-like breast cancer. J Surg Oncol. 2013;107:188–194. doi: 10.1002/jso.23240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cantile M, Franco R, Tschan A, Baumhoer D, Zlobec I, Schiavo G, Forte I, Bihl M, Liguori G, Botti G, Tornillo L, Karamitopoulou-Diamantis E, Terracciano L, Cillo C. HOX D13 expression across 79 tumor tissue types. Int J Cancer. 2009;125:1532–1541. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Makiyama K, Hamada J, Takada M, Murakawa K, Takahashi Y, Tada M, Tamoto E, Shindo G, Matsunaga A, Teramoto K, Komuro K, Kondo S, Katoh H, Koike T, Moriuchi T. Aberrant expression of HOX genes in human invasive breast carcinoma. Oncol Rep. 2005;13:673–679. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]