Abstract

Multiple organ dysfunction syndrome (MODS) has rarely been described in patients with heroin intoxication. Here, we report a rare case of MODS involving six organs, due to heroin intoxication. The patient was a 32-year-old Chinese man with severe heroin intoxication complicated by acute pulmonary edema and respiratory insufficiency, shock, myocardial damage and cardiac insufficiency, rhabdomyolysis and acute renal insufficiency, acute liver injury and hepatic insufficiency, toxic leukoencephalopathy, and hypoglycemia. He managed to survive and was discharged after 10 weeks of intensive care. The possible pathogenesis and therapeutic measures of MODS induced by heroin intoxication and some suggestions for preventing and treating severe complications of heroin intoxication, based on clinical evidence and the pertinent literature, are discussed in this report.

Keywords: Heroin, intoxication, multiple organ dysfunction syndrome

Introduction

MODS is most commonly encountered in patients with trauma, sepsis, or shock [1], and has rarely been described in cases of heroin intoxication. Here, we report a rare case of MODS involving six organs due to heroin intoxication, and discuss the pathogenesis and therapeutic measures.

Case presentation

The Ethics Committee of Gongli Hospital, Pudong New Area, Shanghai approved our study. The reference number is 20140625.

A 32-year-old Chinese man was found to be unconsciousness, and was admitted to our emergency department 3 hours later. Upon admission, he appeared to be dyspneic, orthopneic, cyanotic, sweaty, and coughed up a large quantity of frothy, blood-tinged sputum. He had shallow breathing with a respiratory rate of 6 breaths per minute, temperature of 37.1°C, pulse rate of 114 per minute, and blood pressure of 65/46 mmHg. His bilateral pupils were miotic (1.5 mm) and reacted sluggishly to light. He was in a deep coma with Glasgow Coma Score (GCS) of 3 points. We observed bubbling rales throughout both lung fields during the examination of his chest.

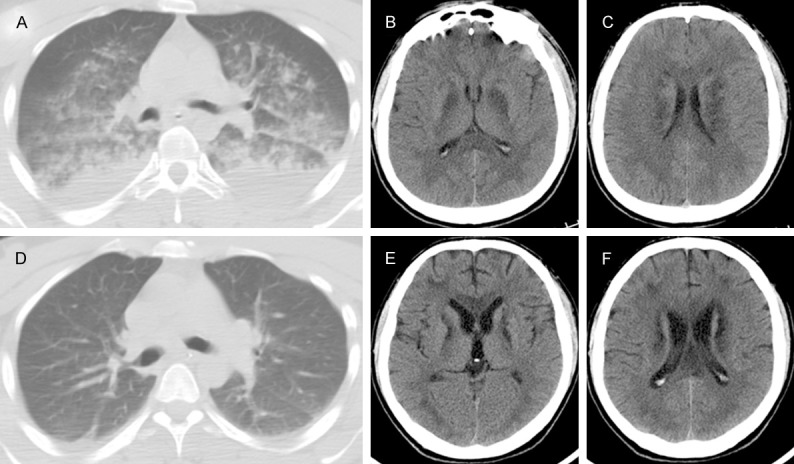

According to the laboratory tests, he had leukocytosis, hypoglycemia, and an elevation of myoglobin, troponin-I, NT-proBNP, CK, CK-MB, LDH, serum Cr, BUN, AST, and ALT levels in blood (Table 1). He was observed to have 3+ myoglobinuria according to urine analysis. The following findings were obtained during blood gas analysis: severe acidosis (pH, 6.99), CO2 retention (PaCO2, 70 mmHg), and severe hypoxemia (PaO2, 35 mmHg; SaO2, 61%; Table 2). Monoacetylmorphine and morphine were also detected in urine during toxicological analysis. Based on a computed tomography (CT) scan of his chest, he was found to have bilateral fluffy infiltrates and exudates, pulmonary interstitial congestion and edema, and bilateral small pleural effusion (Figure 1A). During his head CT scan, extensive symmetric low attenuation involving the cerebellum, brain stem, basal ganglia region, and cerebral white matter were observed (Figure 1B, 1C). Sinus tachycardia was observed in his ECG. His CVP was 12 mmHg.

Table 1.

Laboratory test results of patient during first two weeks

| Day 1 | Day 2 | Day 3 | Day 5 | Day 7 | Day 14 | Normal range | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WBC (109/l) | 19.13 | 21.43 | 19.87 | 11.39 | 15.59 | 9.59 | 4.0~10.0 |

| Troponin-I (ng/ml) | 9.67 | 5.49 | 1.0 | 0.4 | 0.030 | — | <0.034 |

| CK (u/l) | 454.50 | 10120 | 2200 | 577.2 | 135 | — | 26.0~140.0 |

| CKMB (ng/ml) | 70.70 | 148.2 | 102 | 40.6 | 22 | — | 0.0~24.0 |

| myoglobin mb (ng/ml) | 2000 | 1267 | 830 | 145 | 55 | — | 0.0~61.5 |

| Cr (umol/l) | 241 | 127 | 84 | 58 | 52 | 48 | 41.0~144.0 |

| BUN(mmol/L) | 8.30 | 11.70 | 9.4 | 12.3 | 7.0 | 6.7 | 2.80~8.20 |

| AST (u/l) | 155.00 | 216.20 | 210 | 206 | 150 | 57 | <65.0 |

| ALT (u/l) | 61.00 | 105.40 | 156 | 330 | 116 | 36 | <40.0 |

| NT-proBNP (pg/ml) | 356 | 1280 | 835 | 410 | — | — | <500.0 |

| Blood sugar (mmol/l) | 2.01 | 5.3 | 8.7 | 5.4 | 8.1 | 6.6 | 3.9~5.6 |

| Myoglobinuria | +++ | +++ | + | - | — | — | — |

Table 2.

Vital sign and oxygenation of patient during hospitalization

| Before treatment | After treatment | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||||

| Day 1 | Day 2 | Day 3 | Day 5 | Day 7 | Day 14 | Day 81 | ||

| T (°C) | 37.1 | 38.2 | 38.3 | 37.8 | 37 | 37.7 | 38.2 | 36.9 |

| P (beat/min) | 114 | 116 | 122 | 66 | 79 | 72 | 80 | 116 |

| RR (beat/min) | 6 | 16 | 14 | 17 | 21 | 23 | 18 | 20 |

| BP (mmHg) | 65/46 | 94/55 | 105/57 | 107/55 | 144/80 | 119/61 | 131/60 | 145/85 |

| Pupil (mm) | 1.5/1.5 | 2/2 | 1.5/1.5 | 3/3 | 3/3 | 4/4 | 3.5/3.5 | 4 |

| GCS | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 8 | 8 | 10 | 15 |

| CVP (mmHg) | — | 12 | 10 | 10 | 14.5 | 11.5 | — | — |

| FiO2 (%) | 21 | 100 | 70 | 40 | 40 | 40 | 40 | 29 |

| PEEP (cmH2O) | — | 5 | 5 | 5 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| PaO2 (mmHg) | 35 | 85 | 113 | 114 | 104 | 96 | 98 | 97 |

| PaCO2 (mmHg) | 70 | 50 | 33 | 37 | 33.80 | 36.70 | 41 | 42.4 |

| PaO2/FiO2 | 170 | 85.30 | 161 | 285 | 260 | 240 | 245 | 334 |

Figure 1.

CT scan of chest revealed bilateral fluffy infiltrates and exudation, pulmonary interstitial congestion and edema, bilateral small pleural effusion (A). CT scan of head revealed marked low attenuation involving basal ganglia region (B), and cerebral white matter (C). After treatment, follow up CT scan of chest showed clearing of bilateral lung field (D). Follow up CT scan of head showed improvement of low attenuation in basal ganglia region (E), and cerebral white matter (F).

The patient was diagnosed with severe heroin intoxication complicated by acute pulmonary edema and respiratory insufficiency, shock, myocardial damage and cardiac insufficiency, rhabdomyolysis and acute renal insufficiency, acute liver injury and hepatic insufficiency, toxic encephalopathy, and hypoglycemia. Endotracheal intubation was performed on the patient and mechanical ventilation was initiated. He was administered a bolus of 50% glucose (50 mL) to correct for hypoglycemia, an infusion of naloxone for detoxification, dopamine and volume loading to correct for shock, and sodium bicarbonate to alkalinize urine. Furthermore, he was administered glycerol fructose and human blood albumin for treating cerebral edema and mild hypothermia therapy for protecting cerebral cells. Supporting care was provided for the functioning of organs, such as the heart, brain, lungs, liver, and kidneys.

On the 2nd day, the patient’s respiratory and circulatory functions were improved, and vital signs became stable (Table 2). On the 7th day, his serum myoglobin level and myocardial enzyme spectrum were restored to normal; clearing of the bilateral lung fields was observed on a follow-up chest CT scan (Figure 1D). On the 14th day, the patient’s serum Cr, BUN, AST, and ALT levels were restored to normal. Furthermore, the patient’s consciousness improved (GCS, 10 points). However, he had increased muscle tension in all four limbs; the muscle force in both arms and legs was 2/5 and 3/5, respectively. The Babinski sign was positive in both lower limbs. Tracheotomy was performed because the patient required further mechanical ventilation support for respiration. Three weeks later, the patient’s consciousness recovered and respiratory function was restored. Therefore, the patient was successfully weaned-off the mechanical ventilation. Ten weeks later, an improvement of leukoencephalopathy (Figure 1E, 1F) was observed in a follow-up head CT scan, and the patient was discharged.

Discussion

Various complications of heroin intoxication, such as pulmonary edema [2], shock [3], myocardial damage, acute renal failure [4], rhabdomyolysis [5,6], and leukoencephalopathy [7-10] have been described in the literature. However, MODS induced by heroin intoxication is rarely reported. A case of heroin intoxication with damage and dysfunction to six organs has not been previously reported.

There are various hypotheses for the pathogenesis of heroin intoxication complications, including the primary toxic role of heroin [4], hypoxia [11], ischemia-reperfusion injury [6,12], anaphylactic reactions, and the toxic role of adulterants [13]. However, recent investigators did not find enough evidence to support the hypotheses of anaphylactic reactions and the toxic role of adulterants [6,14].

Possible causes of MODS in this case include hypoglycemia, prolonged hypoxia, and ischemia caused by respiratory and circulatory depression due to heroin intoxication [3,15]. These causes can lead to organ edema and dysfunction [16] because ischemia and hypoxia can result in acidosis and increase capillary permeability. In addition, ischemia and hypoxia directly affect the ATP synthesis of cells, which result in damage to cell membranes, mitochondria and lysosomes, and eventually lead to cell apoptosis and necrosis [1,16,17]. Hypoglycemia decreases anaerobic glycolysis and accelerates the depletion of ATP in hypoxia, which further increases damage to tissues and organs [1,18]. Ischemia-reperfusion produces a large quantity of oxygen free radicals, which can also cause damage to tissues and organs [12]. Rhabdomyolysis can cause the release of cell contents into blood, which further damages tissues and organs [4]. Cell apoptosis and necrosis, and damage to tissues and organs eventually lead to MODS. Based on these findings, we thought that the pathogenesis of MODS induced by heroin intoxication should be the consequences of the primary toxic role of heroin, hypoglycemia, prolonged hypoxia, and ischemia-reperfusion injury.

Mortality is higher among patients of heroin intoxication complicated by MODS, if they do not receive timely and effective medical care [19]. Therefore, therapeutic measures should include timely and effectively treating respiratory and circulatory failure to correct for ischemia and hypoxia, and supporting and protecting the main organ functions.

Conclusion

Heroin intoxication complicated by MODS is very rare. The pathogenesis of MODS is presumed to be due to the primary toxic role of heroin, hypoglycemia, prolonged hypoxia, and ischemia-reperfusion. Timely and effectively treating respiratory and circulatory failure to correct for ischemia and hypoxia, and supporting and protecting organ functions are key therapeutic approaches to prevent and successfully treat patients with MODS due to heroin intoxication.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the Key Discipline Construction Project of Pudong Health Bureau of Shanghai (PWZx2014-08), the Outstanding Leaders Training Program of Pudong Health Bureau of Shanghai (PWR12014-05) and the Program for the Development of Science and Technology of Pudong Science and Technology committee of Shanghai (No. PKJ2014-Y21).

Disclosure of conflict of interest

None.

References

- 1.Ramírez M. Multiple organ dysfunction syndrome. Curr Probl Pediatr Adolesc Health Care. 2013;43:273–277. doi: 10.1016/j.cppeds.2013.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Morrison WJ, Wetherill S, Zyroff J. The acute pulmonary edema of heroin intoxication. Radiology. 1970;97:347–351. doi: 10.1148/97.2.347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Remskar M, Noc M, Leskovsek B, Horvat M. Profound circulatory shock following heroin overdose. Resuscitation. 1998;38:51–53. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9572(98)00065-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schwartzfarb L, Singh G, Marcus D. Heroin associated rhabdomyolysis with cardiac involvement. Arch Intern Med. 1977;137:1255–1257. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Scherrer P, Delaloye-Bischof A, Turini G, Perret C. Myocardial involvement in nontraumatic rhabdomyolysis following an opiate overdose. Schweiz Med Wochenschr. 1985;115:1166–1170. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Melandri R, Re G, Lanzarini C, Rapezzi C, Leone O, Zele I, Rocchi G. Myocardial damage and rhabdomyolysis associated with prolonged hypoxic coma following opiate overdose. Clin Toxicol. 1996;34:199–203. doi: 10.3109/15563659609013770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wolters EC, Van Wijngaarden GK, Stam FC, Rengelink H, Lousberg RJ, Schipper ME, Verbeeten B. Leucoencephalopathy after inhaling “heroin” pyrolysate. Lancet. 1982;2:1233–1236. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(82)90101-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen CY, Lee KW, Lee CC, Chin SC, Chung HW, Zimmerman RA. Heroin-induced spongiform leukoencephalopathy: value of diffusion MR imaging. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2000;24:735–737. doi: 10.1097/00004728-200009000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Keogh CF, Andrews GT, Spacey SD, Forkheim KE, Graeb DA. Neuroimaging features of heroin inhalation toxicity: “Chasing the Dragon”. AJR. 2003;180:847–850. doi: 10.2214/ajr.180.3.1800847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chang WL, Chang YK, Hsu SY, Lin GJ, Chen SC. Reversible delayed leukoencephalopathy after heroin intoxication with hypoxia: a case report. Acta Neurol Taiwan. 2009;18:198–202. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Steinberg AD, Karliner JS. The clinical spectrum of heroin pulmonary edema. Arch Intern Med. 1968;122:122–127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Odeh M. The role of reperfusion-induced injury in the pathogenesis of the crush syndrome. N Engl J Med. 1991;324:1417–1422. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199105163242007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Citron BP, Halpern M, McCarron M, Lundberg GD, McCormick R, Pincus IJ, Tatter D, Haverback BJ. Necrotizing angiitis associated with drug abuse. N Engl J Med. 1970;283:1003–1011. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197011052831901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dettmeyer R, Schmidt P, Musshoff F, Dreisvogt C, Madea B. Pulmonary edema in fatal heroin overdose: immunohistological investigations with IgE, collagen IV and laminin-no increase of defects of alveolar-capillary membranes. Forensic Sci Int. 2000;110:87–96. doi: 10.1016/s0379-0738(00)00148-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sporer KA. Acute heroin overdose. Ann Intern Med. 1999;130:584–590. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-130-7-199904060-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Drinker CK. Pulmonary edema and inflammation. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press; 1945. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Visweswaran P, Guntupalli LJ. Rhabdomyolysis. Crit Care Clin. 1999;15:415–428. doi: 10.1016/s0749-0704(05)70061-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dave KR, Pileggi A, Raval AP. Recurrent hypoglycemia increases oxygen glucose deprivation-induced damage in hippocampal organotypic slices. Neurosci Lett. 2011;496:25–29. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2011.03.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zador D, Sunjic S, Darke S. Heroin-related deaths in New South Wales, 1992: toxicological findings and circumstances. Med J Aust. 1996;164:204–207. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.1996.tb94136.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]