Abstract

Background: Gout is an inflammatory disease in which genetic factors play a role. ABCG2 is a urate transporter, and the Q141K and Q126X variants of ABCG2 have been associated with a risk of developing gout, though previous studies of these associations have been inconsistent. Therefore, we conducted a meta-analysis to explore the relationship between these genetic variants and gout. Methods: We examined 8 electronic literature databases. In total, 9 eligible articles on the associations between the Q141K (rs2231142) and Q126X (rs72552713) variants and gout risk, including 11 case-control studies were selected. We used odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) to assess the strength of these relationships in dominant, recessive, and co-dominant models. Results: This study included 6652 participants (2499 gout patients and 4153 controls). The Q141K variant was found to significantly increase the risk of gout in Asians (dominant model: OR=2.64, 95% CI=2.04-3.43, P=0.02 for heterogeneity; recessive model: OR=3.19, 95% CI=2.56-3.97, P=0.28 for heterogeneity; co-dominant model: OR=1.37, 95% CI=1.18-1.59, P=0.09 for heterogeneity) and other populations (dominant model: OR=1.85, 95% CI=1.20-2.85, P<0.0001 for heterogeneity; recessive model: OR=3.78, 95% CI=2.28-6.27, P=0.19 for heterogeneity; co-dominant model: OR=1.48, 95% CI=1.26-1.74, P=0.19 for heterogeneity). The Q126X variant also significantly increased the risk of gout in Asians (dominant model: OR=3.87, 95% CI=2.07-7.24, P=0.06 for heterogeneity). Conclusions: These results suggest associations between the rs2231142 and rs72552713 ABCG2 gene polymorphisms and gout risk, which led to unfavorable outcomes. However, studies with larger sample sizes and homogeneous populations should be performed to confirm these results.

Keywords: Gout, Q141K, Q126X, single nucleotide polymorphism, meta-analysis

Introduction

Gout is a recurrent relapsing inflammatory disease, caused by the precipitation of monosodium urate (MSU) crystals in the joints and soft tissues. Gout is characterized by intense pain that typically persists for approximately one week. In recent years, the prevalence and incidence of gout has been increasing. In 2001 [1], the prevalence of gout was only 0.33% in Shanghai. In 2009, Yu-Hong Jia et al. [2] reported an increased prevalence of gout of as high 1.21% in Tangshan. Today, the prevalence of gout has increased to 1.23% [3]. In addition, Edward and colleagues [4] also reviewed the epidemiology of gout and suggested that the disease is becoming more prevalent. As a result of its increasing prevalence, gout has attracted public attention.

Previous studies demonstrate that environmental exposure and genetic factors play important roles in the development of gout. Jennifer et al. [5] demonstrated that body mass index (BMI), total fat mass, serum triglycerides and serum glucose levels were significantly increased in gout patients. Ling-Qin Li [6] found that hyperuricemia, BMI, high triglycerides, hypertension, a high purine diet, drinking and smoking increase the risk of gout. Previous studies have demonstrated that genetic variations in solute carrier family 2, member 9 (SLC2A9) [7]; solute carrier family 22, member 11 (SLC22A11) [8]; solute carrier family 17, member 1 (SLC17A1) [9]; coding for PDZ domain containing 1 (PDKZ1) [10] and ATP-binding cassette, subfamily G, member 2 (ABCG2) [11] might increase the risk of gout.

ABCG2 is a urate transporter that excretes uric acid [12]. According to gene sequencing analysis, ABCG2 contains more than 80 different single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) loci. Among these, Q141K and Q126X are the most commonly studied. SNP rs2231142, also referred to as C421A or Q141K in ABCG2, is located in exon 5 [10] and substitutes glutamic acid for diaminocaproic acid. Previous studies have reported a relationship between rs2231142 and gout. SNP rs72552713, also referred to as C376T or Q126X in ABCG2, has also been shown to play a role in gout. However, due to small sample sizes and data quality, inconsistent results have been reported. To address these issues, we performed a meta-analysis to explore the roles of rs2231142 and rs72552713 in gout.

Methods

Search strategy

We searched for published articles in eight electronic literature databases (Chaoxing Medalink, Wangfang Data, Weipu, Chinese Biomedical Literature Service System, China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI), Chinese Science Citation Database (CSCD), Ebsco Science Direct and Pubmed). No limit was imposed on publication dates, and the last search update was performed on May 30, 2015. The literature search was performed in English and Chinese using the following primary key words: gout, ABCG2, C421A, Q141K, rs2231142, C376T, Q126X, and rs72552713.The following index terms were used: gout and ABCG2, gout and C421A, gout and Q141K, gout and rs2231142, gout and C376T, gout and Q126X, and gout and rs72552713.

Selection criteria

In this meta-analysis, we established the following inclusion criteria: (1) the publication must be a genetic connectedness study regarding gout and an ABCG2 gene polymorphism; (2) the diagnostic criteria [13] must adhere to the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) preliminary diagnostic criteria for acute gout; (3) the publication must be a case-control study; (4) the participants must not have serious diseases other than gout; (5) the cases and controls must include specific genotype distribution data; (6) the genotype distribution of the control group must satisfy Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (HWE); and (7) if a study contained more than one more sample, each sample was used for this meta-analysis.

Quality assessment

Two authors selected studies based on the selection criteria described. Disagreements were resolved by consulting a third author. If more than one article described the same study, we selected the best article and described those with incomplete data. Then, we performed a quality assessment. The assessment criteria were based on the STREGA (STrengthening the Reporting of Genetic Association studies) principle [14], which consists of six requirements. If the included studies fulfilled three or more of those requirements, they were considered to be of good quality. Fortunately, the quality of the included studies was high, and we were able to collect the following data from each study: the first author’s name, publication year, country, ethnicity, diagnostic standard of gout, study design, total number of cases and controls, HWE P-value, genotype distribution and genotype frequencies. These data were organized into two tables for analysis.

Statistical analysis

We used Review Manager 5.1 software (The Cochrane Collaboration, Oxford, UK) and Stata software (version 11.0) to perform statistical analyses. Associations between gout susceptibility and the rs2231142 and rs72552713 ABCG2 gene polymorphisms were indicated by the odds ratio (OR) and the corresponding 95% confidence interval (CI). Each relationship was assessed in a dominant model (Q141K: CC compared to AC+AA; Q126X: CC compared to CT+TT), a recessive model (Q141K: AA compared to CC+AC), and a co-dominant model (Q141K: AC compared to CC+AA). We used the I 2 statistic to evaluate heterogeneity between studies, and a fixed effects model (FEM) to calculate the pooled OR and 95% CI if the P-value was greater than 0.05, which indicated no heterogeneity. If heterogeneity was observed, we used a random effects model (REM) to combine eligible data. We examined significant pooled ORs using the Z statistic. To guarantee the stability of the results, we implemented a sensitivity analysis by the sequential removal of individual studies. Publication bias was assessed using funnel plots with Begg’s test and Egger’s test, in which P>0.05 indicated no publication bias.

Results

Search results and study characteristics

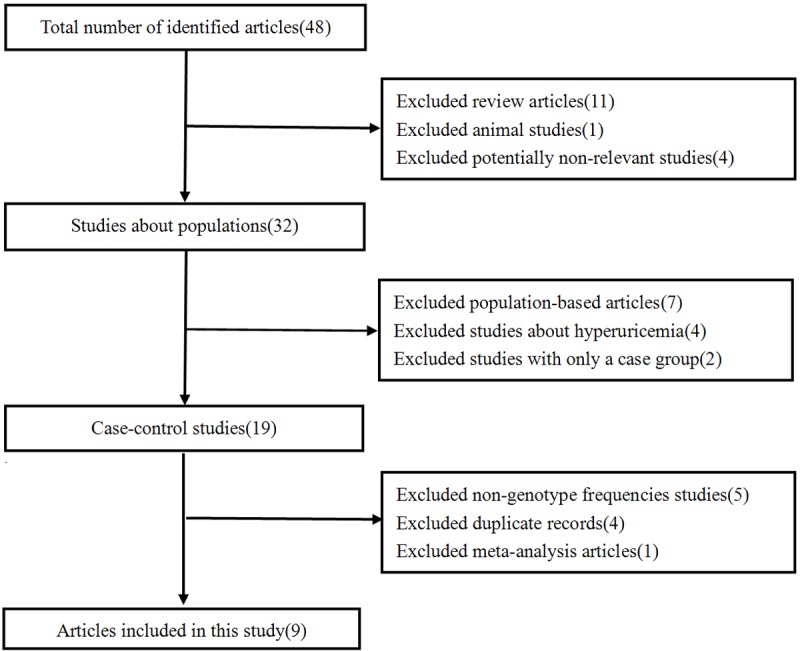

In total, 48 records were identified that analyzed the associations between ABCG2 polymorphisms and gout risk. The following studies were initially excluded: 11 review articles, an animal-based study and 4 potentially irrelevant studies. Among the remaining 32 studies, 13 additional articles were also excluded: 7 studies were based on specific examined populations, 4 studies did not show a relationship to gout and 2 studies lacked control groups. Thus, 19 total case-control publications were ultimately used. An addition 5 studies was excluded from our meta-analysis due to the absence of genotype frequencies, and 4 pairs of studies were published using the same data, leading us to exclude those 4 additional studies. In total, 9 studies were included in our meta-analysis following the exclusion of another meta-analysis article. All of these 9 studies involved the Q141K variant, and only 2 studies referred to the Q126X variant. The study search procedure used is outlined in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of study selection for meta-analysis.

Of these 9 studies, of the Q141K variant, one study contained data for three different ethnicities; therefore, each of these studies was treated separately. Thus, 11 total study populations were pooled for our analyses. These 11 studies included 7 studies from China [15-21], 3 studies from New Zealand [22] and one study from Germany [23]. A total of 2499 gout patients and 4153 controls were recruited for this analysis from these 11 studies. We extracted the characteristics of these studies, which are summarized in Tables 1, 2 of Article 9 on the Q126X variant. These characteristics were derived from 499 gout patients and 671 controls, and are summarized in Table 2.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the included studies (Q141K)

| First author (Ref.) | Year | Ethnicity/country | Diagnostic standard | Study design | Sample size (case/control) | HWE p-value | Genotype distribution (case/control) | Genotype frequency (case/control) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||||

| CC | CA | AA | CC (%) | CA (%) | AA (%) | |||||||

| Wang Qiong (17) | 2014 | Asians China | ACR preliminary diagnostic criteria for acute gout (1977) | Case-control | 185/311 | Yes | 64/157 | 86/126 | 35/28 | 34.6/50.5 | 46.5/40.5 | 18.9/9.0 |

| Zhang Xin-Lei (28) | 2014 | Asians China | ACR preliminary diagnostic criteria for acute gout (1977) | Case-control | 147/321 | Yes | 30/167 | 79/134 | 38/20 | 20.4/52.0 | 53.7/41.7 | 25.9/6.2 |

| Li Fa-Gui (12) | 2011 | Asians China | ACR preliminary diagnostic criteria for acute gout (1977) | Case-control | 200/235 | Yes | 64/103 | 91/112 | 45/20 | 32.0/43.8 | 45.5/47.7 | 22.5/8.5 |

| Amanda 1 (25) | 2010 | Maori New Zealand | ACR preliminary diagnostic criteria for acute gout (1977) | Case-control | 185/215 | Yes | 142/172 | 34/39 | 2/1 | 79.8/81.1 | 19.1/18.4 | 1.1/0.5 |

| Amanda 2 (25) | 2010 | Pacific Islander New Zealand | ACR preliminary diagnostic criteria for acute gout (1977) | Case-control | 173/109 | Yes | 58/69 | 78/36 | 37/4 | 33.5/63.3 | 45.1/33.0 | 21.4/3.7 |

| Amanda 3 (25) | 2010 | Caucasian New Zealand | ACR preliminary diagnostic criteria for acute gout (1977) | Case-control | 214/562 | Yes | 122/425 | 76/125 | 13/8 | 57.8/76.2 | 36.0/22.4 | 6.2/1.4 |

| Danqiu Zhou (36) | 2014 | Asians China | ACR preliminary diagnostic criteria for acute gout (1977) | Case-control | 352/350 | Yes | 87/167 | 181/150 | 84/33 | 24.7/47.7 | 51.4/42.9 | 23.9/9.4 |

| Klaus (32) | 2009 | Caucasian German | ACR preliminary diagnostic criteria for acute gout (1977) | Case-control | 677/1552 | Yes | 500/1241 | 168/299 | 9/12 | 73.9/80.0 | 24.8/19.2 | 1.3/0.8 |

| Zhang Xiu-Juan (36) | 2012 | Asians China | ARA diagnostic criteria for acute gout (1997) | Case-control | 110/236 | Yes | 35/120 | 55/96 | 20/20 | 31.8/50.8 | 50.0/40.7 | 18.2/8.5 |

| You Yu-Quan (39) | 2013 | Asians China | ACR preliminary diagnostic criteria for acute gout (1977) | Case-control | 154/160 | Yes | 48/98 | 78/49 | 28/13 | 31.2/60.3 | 50.6/30.6 | 18.2/8.1 |

| Ye De-Shao (62) | 2012 | Asians China | ACR preliminary diagnostic criteria for acute gout (1977) | Case-control | 102/102 | Yes | 23/53 | 42/40 | 37/9 | 22.5/52.0 | 41.2/39.2 | 36.3/8.8 |

Table 2.

Characteristics of the included studies (Q126X)

| First author (Ref.) | Year | Ethnicity/country | Diagnostic standard | Study design | Sample size (case/control) | HWE p-value | Genotype distribution (case/control) | Genotype frequency (case/control) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||||

| CC | CT | TT | CC (%) | CT (%) | TT (%) | |||||||

| Zhang Xin-Lei (28) | 2014 | Asians China | ACR preliminary diagnostic criteria for acute gout (1977) | Case-control | 136/321 | Yes | 127/320 | 9/1 | 0/0 | 93.4/99.7 | 6.6/0.3 | 0/0 |

| Danqiu Zhou (36) | 2014 | Asians China | ACR preliminary diagnostic criteria for acute gout (1977) | Case-control | 352/350 | Yes | 319/338 | 33/12 | 0/0 | 90.6/96.6 | 9.4/3.4 | 0/0 |

Meta-analysis

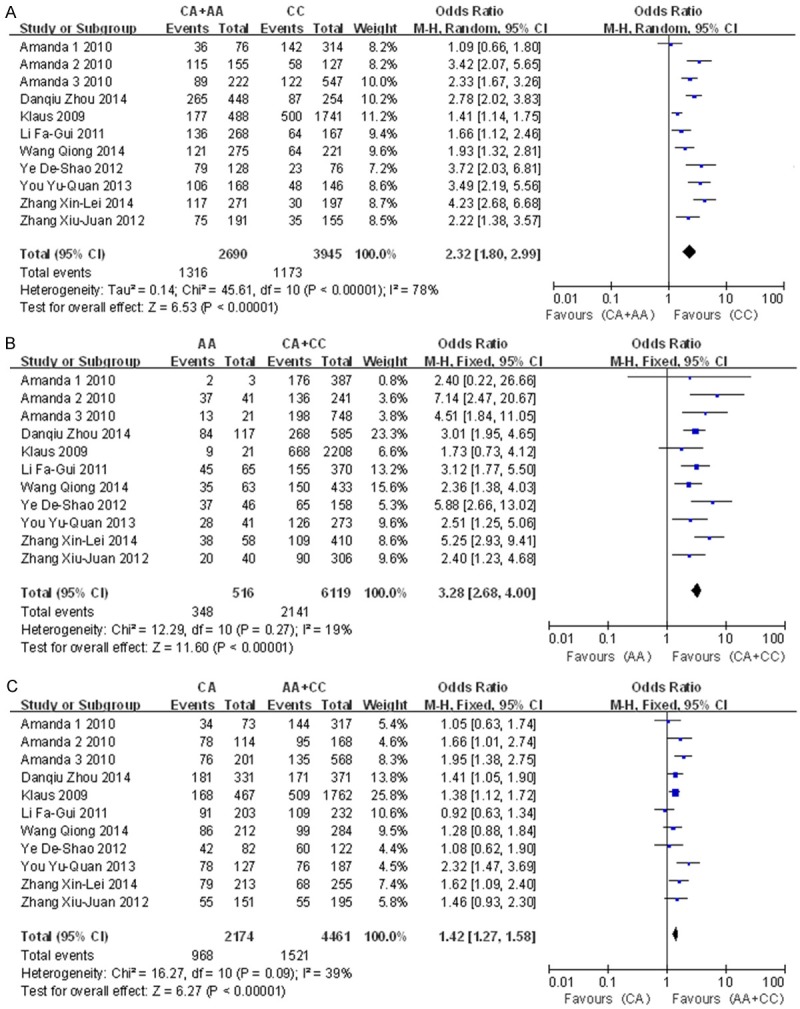

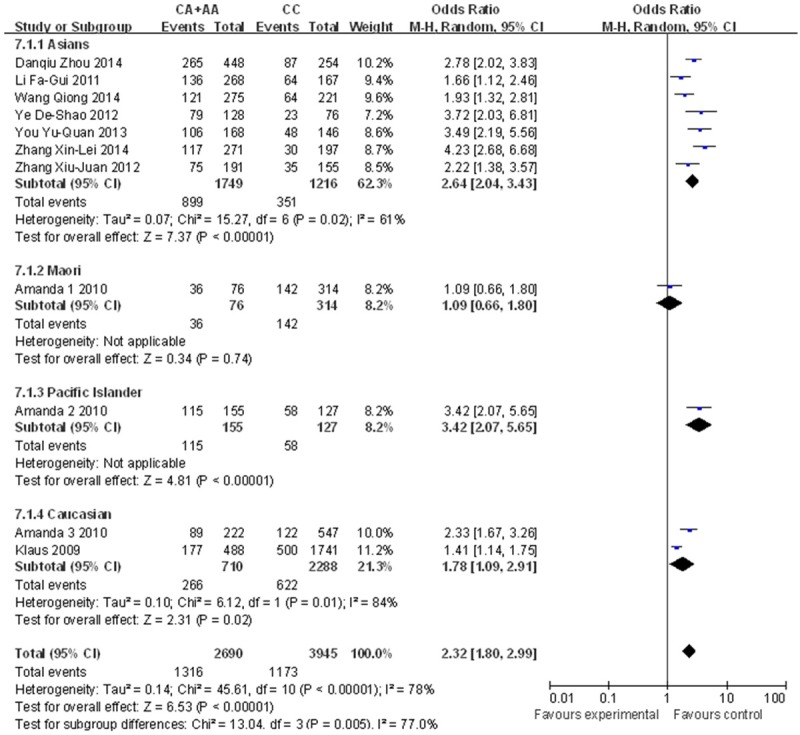

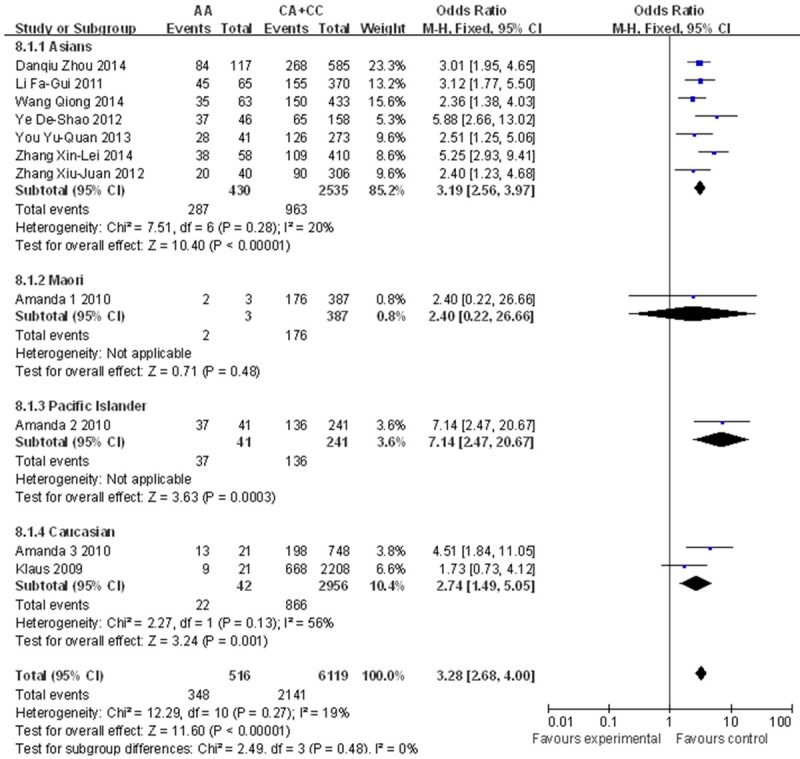

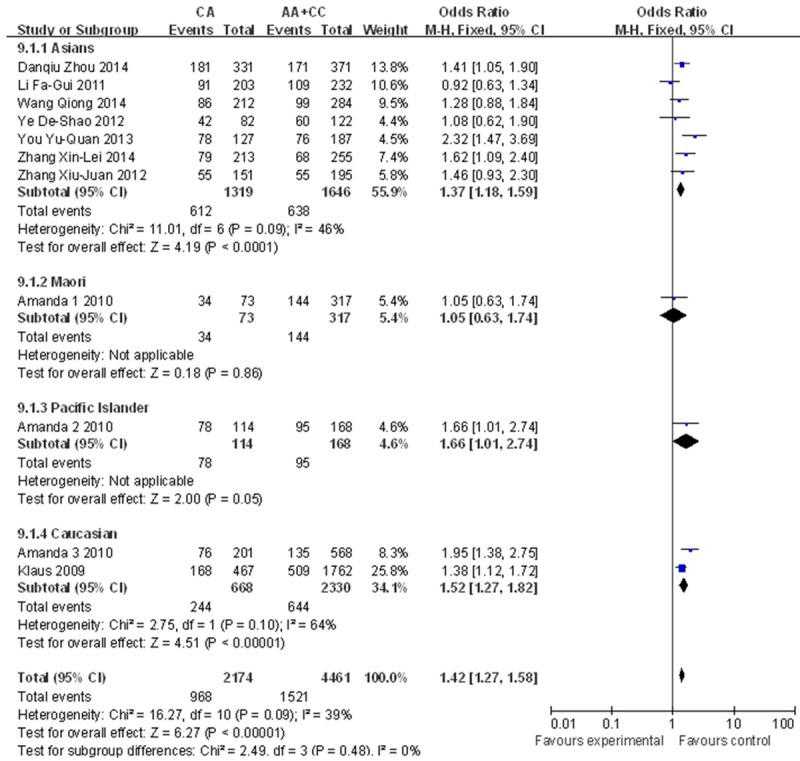

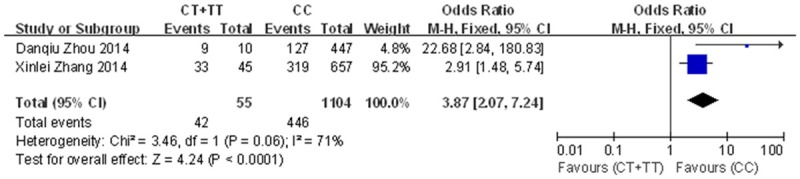

A significant association was found between the rs2231142 polymorphism and gout risk in the dominant model (OR=2.32, 95% CI=1.80-2.99, P<0.0001 for heterogeneity), the recessive model (OR=3.28, 95% CI=2.68-4.00, P=0.27 for heterogeneity) and the co-dominant model (OR=1.42, 95% CI=1.27-1.58, P=0.09 for heterogeneity) (Figure 2). Subgroup analysis by ethnicity also revealed significant associations for both Asians (dominant model: OR=2.64, 95% CI=2.04-3.43, P=0.02 for heterogeneity; recessive model: OR=3.19, 95% CI=2.56-3.97, P=0.28 for heterogeneity; co-dominant model: OR=1.37, 95% CI=1.18-1.59, P=0.09 for heterogeneity) and other populations (dominant model: OR=1.85, 95% CI=1.20-2.85, P<0.0001 for heterogeneity; recessive model: OR=3.78, 95% CI=2.28-6.27, P=0.19 for heterogeneity; co-dominant model: OR=1.48, 95% CI=1.26-1.74, P=0.19 for heterogeneity) (Figures 3, 4 and 5). Our results also demonstrated that the rs72552713 polymorphism can increase the risk of gout in the dominant model: OR=3.87, 95% CI=2.07-7.24, P=0.06 for heterogeneity (Figure 6).

Figure 2.

Forest plot of the associations between the Q141K variant and gout risk using the A: Dominant model (CC compared to AC+AA), B: Recessive model (AA compared to CC+AC), and C: Co-dominant model (AC compared to CC+AA).

Figure 3.

Forest plot describing ethnicity in the dominant model (Q141K).

Figure 4.

Forest plot describing ethnicity in the recessive model (Q141K).

Figure 5.

Forest plot describing ethnicity in the co-dominant model (Q141K).

Figure 6.

Forest plot for the association between the Q126X variant and gout risk using the dominant model (CT+TT compared to CC).

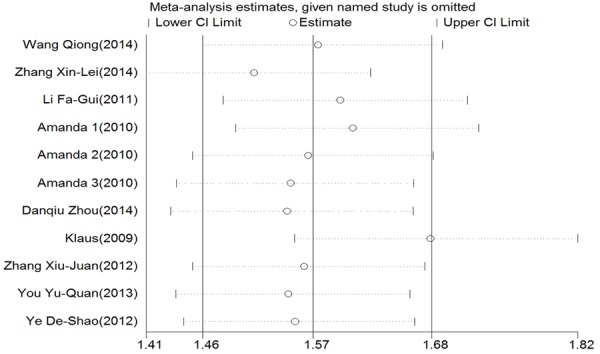

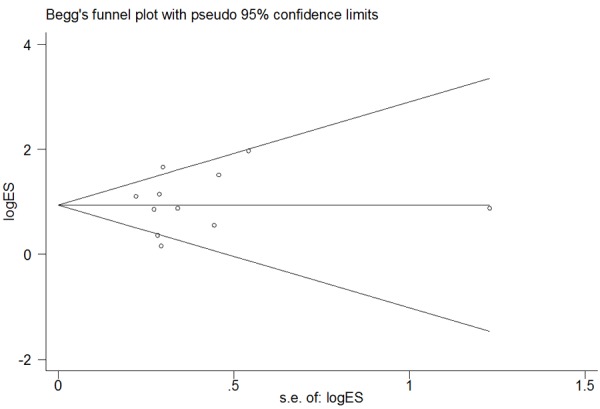

Sensitivity analysis and publication bias

To ensure the stability of our results and given the heterogeneity among studies, we performed a sensitivity analysis by removing studies independently. We did not identify any study that significantly influenced the pooled ORs, indicating that the overall OR was stable (Figure 7). We used funnel plots with Begg’s and Egger’s tests to detect publication bias. The funnel plot was nearly symmetrical, and the Begg’s test (dominant model: P=0.586; recessive model: P=0.484; co-dominant model: P=0.815) and Egger’s test (dominant model: P=0.060, 95% CI=-0.203-8.08; recessive model: P=0.642, 95% CI=-2.70-4.16; co-dominant model: P=0.998, 95% CI=-3.23-3.24) did not reveal significant publication bias (Figure 8).

Figure 7.

Sensitivity analysis for the association between the Q141K variant and gout risk.

Figure 8.

Begg’s funnel plot examining the publication bias of studies using the recessive model (Q141K).

Discussion

Subsequent to the development of genetic technologies, numerous studies examining the association between ABCG2 polymorphisms and gout risk have been reported. Among the ABCG2 polymorphisms, Q141K and Q126X are the most commonly studied. Nevertheless, the role of the Q141K variant in gout risk and the potential for the Q126X variant to increase gout risk are controversial. Lili Zhang et al. [24] demonstrated that rs2231142 is significantly associated with gout in Europeans, Americans, African Americans and Mexican Americans. Hirotaka et al. [25], Kazumasa et al. [11] and Xiaofei Lv [26] also showed that the Q141K variant increases the risk of gout. However, Amanda et al. [22] reported no association of rs2231142 with gout in Maori samples. Until now, there has been no meta-analysis demonstrating the role of Q126X in gout. To address these discrepancies, we performed a meta-analysis to explore the relationships between rs2231142 and rs72552713 and gout, and we conducted a subgroup analysis to identify racial differences in rs2231142.

In our meta-analysis, we identified 11 studies involving 4 ethnicities (Asians, Maori, Pacific Islanders and Caucasians) from 3 countries (China, New Zealand and Germany) and including a total of 6652 participants (2499 gout patients and 4153 controls). Our results suggested that the Q141K variant results in increased gout risk in dominant, recessive, and co-dominant models, and in subgroup analyses, Q126X also increased gout risk in a dominant model. However, heterogeneity had a significant effect on both the dominant model and rs2231142 subgroup analysis. This effect might be explained by confounders such as age, gender and inscrutable environmental factors. Previous studies have demonstrated that gout might be more prevalent in men [27] and postmenopausal women [28]. However, because these data were not included in certain studies we analyzed, we did not estimate the adjusted OR. Gene-environment interactions might also play a significant role in gout risk, which represents a limitation of our meta-analysis.

Ethnic differences are always mentioned by researchers not only in discussions of gout [29] but also in the association between the Q141K polymorphism and gout risk [24,30]. In our meta-analysis, we performed a subgroup analysis based on ethnicity. From this subgroup analysis, we found that regardless of race, the Q141K variant increases the risk of gout. The data indicate that rs2231142 enhances the risk of gout particularly in Pacific Islanders, for whom the OR reached 3.42. However, with respect to the Maori, although the OR revealed a relationship with gout and a tendency toward unfavorable outcomes, the association was not significant as the 95% CI (0.66-1.80) exceeded 1. However, these results might be explained by the critical factor of quantity. Our meta-analysis only included one study of Maori people, one of Pacific Islanders and two of Caucasians; therefore, there might be inconsistencies in our analysis related to sample size. Resolving this issue would require further large-scale analyses.

Gout is caused by hyperuricemia, which manifests as high serum uric acid (SUA) in vivo. Previous studies [12] have demonstrated that ABCG2 is a urate transporter and there is a significant association between hyperuricemia and gout. Hirotaka and colleagues [31,32] divided samples into 4 groups according to ABCG2 function (≤1/4 function, 1/2 function, 3/4 function, and full function) and reported that ABCG2 dysfunction increases gout risk, especially in the group with the lowest ABCG2 function. Abbas et al. [12] found that SLC2A9 and SLC17A3 also increase uric acid concentration and gout risk. Therefore, we should consider gene-gene interactions and linkage disequilibrium to validate our results, the lack of which is a limitation of the current meta-analysis. This meta-analysis did have certain advantages. We identified 9 articles describing 11 studies, ensured the inclusion of an adequate sample size to validate the relationship between the rs2231142 polymorphism and gout risk, and demonstrated the association between rs72552713 polymorphism and gout risk.

Conclusion

Our results suggest that the rs2231142 ABCG2 polymorphism is associated with gout not only in Asians but also in other populations. The rs72552713 ABCG2 polymorphism also plays a role in gout in Asians. Our evidence revealed that Q141K and Q126X are risk factors for the development of gout. Heterogeneity in our model and subgroup analyses and certain limitations of this meta-analysis suggest that additional investigations with large sample sizes using well-designed methods and more homogeneous populations should be performed.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81460153). The authors thank Yunkai Wang for advice on modifying the meta-analysis and Le Zhang for advice on data analysis.

Disclosure of conflict of interest

None.

Abbreviations

- ABCG2

ATP-binding cassette, subfamily G, member 2

- MSU

monosodium urate

- SUA

serum uric acid

- SLC2A9

solute carrier family 2, member 9

- SLC22A11

solute carrier family 22, member 11

- SLC17A1

solute carrier family 17, member 1

- PDKZ1

coding for PDZ domain containing 1

- SNP

single-nucleotide polymorphism

- ACR

American College of Rheumatology

- HWE

Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium

- OR

odds ratio

- CI

confidence interval

- FEM

fixed effects model

- REM

random effects model

References

- 1.Dai SM, Han XH, Shi YQ, et al. Prevalence of rheumatic diseases in Shanghai. Modern Rehabilitation. 2001;5:42–44. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jia YH, Cui LF, Yang WH, et al. Epidemiological survey on morbidity of hyperuricemia and gout in Tangshan mining district. Chin J Coal Industry Med. 2009;12:1933–1935. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhang P, Zhang L, Wang CH, et al. Investigation of hyperuricemia and gout populations in 30-year old in Xingtai. Prac Prev Med. 2014;21:1010–1012. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Roddy E, FRCP DM, Choi H, et al. Epidemiology of gout. Nat Institutes Health. 2014;40:155–175. doi: 10.1016/j.rdc.2014.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee J, Lee JY, Lee JH, Jung SM, Suh YS, Koh JH, Kwok SK, Ju JH, Park KS, Park SH. Visceral fat obesity is highly associated with primary gout in a metabolically obese but normal weighted population: a case control study. Arthritis Res Ther. 2015;17:79. doi: 10.1186/s13075-015-0593-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li LQ, Qing YF, Zhou C, et al. Logistic regression analysis on clinical features and related risk factors of primary gout in the northeastern area of China. Shangdong Med. 2014;54:13–15. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li C, Chu N, Wang B, Wang J, Luan J, Han L, Meng D, Wang Y, Suo P, Cheng L, Ma X, Miao Z, Liu S. Polymorphisms in the presumptive promoter region of the SLC2A9 gene are associated with gout in a Chinese male population. PLoS One. 2012;7:e24561. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0024561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Flynn TJ, Phipps-Green A, Hollis-Moffatt JE, Merriman ME, Topless R, Montgomery G, Chapman B, Stamp LK, Dalbeth N, Merriman TR. Association analysis of the SLC22A11 (organic anion transporter 4) and SLC22A12 (urate transporter 1) urate transporter locus with gout in New Zealand case-control sample sets reveals multiple ancestral-specific sffects. Arthritis Res Ther. 2013;15:R220. doi: 10.1186/ar4417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hollis-Moffatt JE, Phipps-Green AJ, Chapman B, Jones GT, van Rij A, Gow PJ, Harrison AA, Highton J, Jones PB, Montgomery GW, Stamp LK, Dalbeth N, Merriman TR. The renal urate transporter SLC17A1 locus: confirmation of association with gout. Arthritis Res Ther. 2012;14:R92. doi: 10.1186/ar3816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yang Q, Köttgen A, Dehghan A, Smith AV, Glazer NL, Chen MH, Chasman DI, Aspelund T, Eiriksdottir G, Harris TB, Launer L, Nalls M, Hernandez D, Arking DE, Boerwinkle E, Grove ML, Li M, Linda Kao WH, Chonchol M, Haritunians T, Li G, Lumley T, Psaty BM, Shlipak M, Hwang SJ, Larson MG, O’Donnell CJ, Upadhyay A, van Duijn CM, Hofman A, Rivadeneira F, Stricker B, Uitterlinden AG, Paré G, Parker AN, Ridker PM, Siscovick DS, Gudnason V, Witteman JC, Fox CS, Coresh J. Multiple genetic loci influence serum urate and their relationship with gout and cardiovascular disease risk factors. Circ Cardiovasc Genet. 2010;3:523–530. doi: 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.109.934455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yamagishi K, Tanigawa T, Kitamura A, Köttgen A, Folsom AR, Iso H CIRCS Investigators. The rs2231142 variant of the ABCG2 gene is associated with uric acid levels and gout among Japanese people. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2010;49:1461–1465. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keq096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dehghan A, Köttgen A, Yang Q, Hwang SJ, Kao WL, Rivadeneira F, Boerwinkle E, Levy D, Hofman A, Astor BC, Benjamin EJ, van Duijn CM, Witteman JC, Coresh J, Fox CS. Association of three genetic loci with uric acid concentration and risk of gout:a genome-wide association study. Lancet. 2008;372:1953–1961. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61343-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wallace SL, Robinson H, Masi AT, Decker JL, McCarty DJ, Yü TF. Preliminary creteria for the classification of the acute arthritis of primary gout. Arthritis Rheum. 1977;20:895–900. doi: 10.1002/art.1780200320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Little J, Higgins JP, Joannidis JP, Moher D, Gagnon F, von Elm E, Khoury MJ, Cohen B, Davey-Smith G, Grimshaw J, Scheet P, Gwinn M, Williamson RE, Zou GY, Hutchings K, Johnson CY, Tait V, Wiens M, Golding J, van Duijn C, McLaughlin J, Paterson A, Wells G, Fortier I, Freedman M, Zecevic M, King R, Infante-Rivard C, Stewart AF, Birkett N. Strengthening the reporting of genetic association study (STREGA): an extension of the STROBE statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e22. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang Q, Wang C, Wang XB, et al. Association between gout and polymorphisms of rs2231142 in ABCG2 in female Han Chinese. Prog Modern Biomed. 2014;14:2437–2440. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang XL. The association between ABCG2 polymoephism and gout and hyperuricemia by establish queue about staff hyperuricemia. Academic Dissertation. 2014:1–70. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li FG, Chu Y, Meng DM, Tong YW. Association of ABCG2 gene C421A polymorphism and susceptibility of primary gout in Han Chinese males. Zhonghua Yi Xue Yi Chuan Xue Za Zhi. 2011;28:683–685. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.1003-9406.2011.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhou D, Liu Y, Zhang X, Gu X, Wang H, Luo X, Zhang J, Zou H, Guan M. Functional polymorphisms of the ABCG2 gene are associated with gout disease in the Chinese Han male population. Int J Mol Sci. 2014;15:9149–9159. doi: 10.3390/ijms15059149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang XJ. Association between rs13124007, rs6850166 and rs2231142 polymorhphisms and gout in the Chinese Han male population. Academic Dissertation. 2012:1–38. [Google Scholar]

- 20.You YQ. Study on relationship between single nucleotide polymorphism of the SLC2A9, SLC17A3, ABCG2 gene genetic susceptibility to gout. Academic Dissertation. 2012:1–46. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ye DS. Analysis of gout risk and urate transporter polymorphism in the Chinese Han population. Academic Dissertation. 2012:1–63. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Phipps-Green AJ, Hollis-Moffatt JE, Dalbeth N, Merriman ME, Topless R, Gow PJ, Harrison AA, Highton J, Jones PB, Stamp LK, Merriman TR. A strong role for the ABCG2 gene in susceptibility to gout in New Zealand Pacific Island and Caucasian, but not Maori, case and control sample sets. Hum Mol Genet. 2010;19:4813–4819. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddq412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stark K, Reinhard W, Grassl M, Erdmann J, Schunkert H, Illig T, Hengstenberg C. Common polymorphisms influencing serum uric acid levels contribute to susceptibility to gout, but not to Coronary Artery disease. PLoS One. 2009;4:e7729. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang L, Spencer KL, Voruganti VS, Jorgensen NW, Fornage M, Best LG, Brown-Gentry KD, Cole SA, Crawford DC, Deelman E, Franceschini N, Gaffo AL, Glenn KR, Heiss G, Jenny NS, Kottgen A, Li Q, Liu K, Matise TC, North KE, Umans JG, Kao WH. Association of functional polymorphism rs2231142 (Q141K) in the ABCG2 gene with serum uric acid and gout in 4 US populations. Am J Epidemiol. 2013;177:923–932. doi: 10.1093/aje/kws330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Matsuo H, Tomiyama H, Satake W, Chiba T, Onoue H, Kawamura Y, Nakayama A, Shimizu S, Sakiyama M, Funayama M, Nishioka K, Shimizu T, Kaida K, Kamakura K, Toda T, Hattori N, Shinomiya N. ABCG2 variant has opposing effects on onset ages of Parkinson’s disease and gout. Ann Clin Transl Neurol. 2015;2:302–306. doi: 10.1002/acn3.167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lv X, Zhang Y, Zeng F, Yin A, Ye N, Ouyang H, Feng D, Li D, Ling W, Zhang X. The association between the polymorphism rs2231142 in the ABCG2 gene and gout risk: a meta-analysis. Clin Rheumatol. 2014;33:1801–1805. doi: 10.1007/s10067-014-2635-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cea Soriano L, Rothenbacher D, Choi HK, García Rodríguez LA. Contemporary epidemiology of gout in the UK general population. Arthritis Res Ther. 2011;13:R39. doi: 10.1186/ar3272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hak AE, Curhan GC, Grodstein F, Choi HK. Menopause, postmenopausal hormone use and risk of incident gout. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69:1305–1309. doi: 10.1136/ard.2009.109884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Maynard JW, McAdams-DeMarco MA, Law A, Kao L, Gelber AC, Coresh J, Baer AN. Racial differences in gout incidence in a population-based cohort: atherosclerosis risk in communities study. Am J Epidemiol. 2013;179:576–583. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwt299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dong Z, Guo S, Yang Y, Wu J, Guan M, Zou H, Jin L, Wang J. Association between ABCG2 Q141K polymorphism and gout risk affected by ethnicity and gender: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Rheum Dis. 2015;18:382–391. doi: 10.1111/1756-185X.12519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Matsuo H, Nakayama A, Sakiyama M, Chiba T, Shimizu S, Kawamura Y, Nakashima H, Nakamura T, Takada Y, Oikawa Y, Takada T, Nakaoka H, Abe J, Inoue H, Wakai K, Kawai S, Guang Y, Nakagawa H, Ito T, Niwa K, Yamamoto K, Sakurai Y, Suzuki H, Hosoya T, Ichida K, Shimizu T, Shinomiya N. ABCG2 dysfunction causes hyperuricemia due to both renal urate underexcretion and renal urate overload. Sci Rep. 2014;4:3755. doi: 10.1038/srep03755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Matsuo H, Ichida K, Takada T, Nakayama A, Nakashima H, Nakamura T, Kawamura Y, Takada Y, Yamamoto K, Inoue H, Oikawa Y, Naito M, Hishida A, Wakai K, Okada C, Shimizu S, Sakiyama M, Chiba T, Ogata H, Niwa K, Hosoyamada M, Mori A, Hamajima N, Suzuki H, Kanai Y, Sakurai Y, Hosoya T, Shimizu T, Shinomiya N. Common dysfunctional variants in ABCG2 are a major cause of early-onset gout. Sci Rep. 2013;3:2014. doi: 10.1038/srep02014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]