Abstract

This article reviews recent evidence on urate deposition and the opportunity for a therapeutic approach. We reviewed Pubmed 2013–2015 literature using the search terms ‘deposition’ with ‘hyperuricaemia’, ‘gout’, ‘ultrasonography’, ‘DECT’ (dual-energy computed tomography), ‘radiography’, ‘CT’(computed tomography), ‘MRI’ (magnetic resonance imaging), or ‘cardiovascular’, in addition to a digital bibliographic library compiled by the authors with 2072 papers on hyperuricaemia and gout. Relevant papers on the topic were selected. Recent evidence, mostly based on imaging studies, showed a continuum from hyperuricaemia to deposition and clinical manifestations. Chronic inflammation and structural damage may be present even in asymptomatic patients with crystal-proved deposition. The impact of early intervention in patients with asymptomatic deposition either on vascular outcomes or further structural joint damage has not been demonstrated yet. In conclusion, a worldwide definition of gout is still lacking, stages from hyperuricaemia to clinical gout not being definitively defined. Although there is increasing interest on the impact of early deposits on joint damage and cardiovascular outcomes, robust evidence is still lacking to fully support interventions.

Keywords: deposition, dual-energy computed tomography, gout, gout suppressant, hyperuricaemia, ultrasonography

Introduction

Gout has been considered as the clinical consequence of the nucleation, growth and aggregation of monosodium urate crystals (MSUCs) in tissues, mostly in structures of the musculoskeletal system. Although academically gout has been divided into different clinical stages, namely acute, intercritical and chronic, this classification may be misleading for both patients and physicians [Perez-Ruiz et al. 2014a], especially as to consider whether gout is not present neither has consequences in the absence of clinical manifestations [Perez-Ruiz et al. 2015], and may subsequently lead to mismanagement [Doherty et al. 2012].

As an example, indications for a recent urate-lowering medication (ULM), such as febuxostat, may differ as definitions of gout vary. Whereas in the EU it is labelled for the ‘treatment of chronic hyperuricaemia in conditions where urate deposition has already occurred (including a history, or presence of, tophus and/or gouty arthritis)’ [EMA, 2015], which may include unequivocal evidence based on imaging or tissue deposits, in the USA, febuxostat is labelled ‘for the chronic management of hyperuricemia in patients with gout’ [FDA, 2015], not specifying a definition for gout, and in Australia it is indicated for the ‘treatment of chronic symptomatic hyperuricaemia in conditions where urate deposition has already occurred (gouty arthritis and/or tophus formation) in adults with gout’ (TGAeBS, 2015), that is, symptoms are needed to apply for an indication.

Definitions

Unfortunately, there is no common definition of gout accepted worldwide, as there is for diabetes or hypertension, which are not necessarily associ-ated with symptoms [Perez-Ruiz et al. 2014a]. Therefore, the pathway from sustained or chronic hyperuricaemia to hyperuricaemia with deposition and gout is nowadays a matter of debate. Making the following definitions ‘crystal-clear’ may help the following discussion.

Hyperuricaemia

Despite the definition of hyperuricaemia being commonly based on the distribution of serum urate (sUA) in the population, which therefore may vary depending on age and gender, from the pathophysiological point of view of MSUC deposition, hyperuricaemia is defined as sUA levels above the threshold for saturation of urate in body fluids, which is considered to be over 0.40 mmol/L [Becker and Ruoff, 2010]. A recent change of definition for hyperuricaemia of gout to a more operative definition has been proposed to overlap that of the therapeutic target for urate-lowering interventions, that is, 0.36 mmol/L [Bardin and Richette, 2014].

Hyperuricaemia with deposition

Imaging studies based on ultrasonography have shown the continuum from hyperuricaemia to deposition [Chowalloor and Keen, 2013]. In 26 asymptomatic subjects showing hyperuricaemia over 2 years, ultrasonography examination of the knees and first metatarsophalangeal joints showed findings of urate deposition in 11/26 (42%), ultrasonography-guided aspiration demonstrating MSUCs in 9/11 (82%) [De Miguel et al. 2011]. These results were confirmed in a controlled study, in which 8/50 (16%) asymptomatic hyperuricaemic subjects also showed intra-articular tophi [Pineda et al. 2011]. More recently, dual-energy computed tomography (DECT) imaging showed urate deposits in 6/25 (24%) subjects with asymptomatic hyperuricaemia, in 11/14 (79%) patients with early (< 3 years) gout, and in 16/19 (84%) patients with established gout (> 3 years) [Dalbeth et al. 2015], suggesting that a critical amount of MSUC deposits may be needed for the development of clinical manifestations.

Therefore a gout condition defined as ‘asymptomatic MSUC deposits’ has been proposed [Bardin and Richette, 2014]. Also, a staging classification has been proposed to differentiate ‘hyperuricaemia, without evidence of MSUC deposition’, asymptomatic MSUC deposition (by microscopy or advanced imaging), but without signs or symptoms of gout [Dalbeth and Stamp, 2014].

Gout

Taking into account the previous considerations, it seems that the definition of gout implies the presence of symptoms. Nevertheless, it seems to be more simply and conceptually applicable to consider gout as ‘the presence of a nonphysiological material (MSUCs) in tissues, independent of the presence or absence of clinical manifestations’ [Perez-Ruiz et al. 2014a]. This definition is applicable to patients with crystal-proved MSUC deposits, including subclinical, early and late gout with typical, atypical, acute or chronic clinical manifestations.

Pathophysiological importance of urate deposition

The key point to consider in therapeutic intervention in subjects with asymptomatic MSUC deposition would be to demonstrate that such deposits are not inert in tissues, and that there is a positive outcome when such interventions are performed. Imaging that captures inflammation, namely ultrasonography or gadolinium-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may help to evaluate further the relationship between MSUC deposition, inflammation and vascular outcomes [Perez-Ruiz et al. 2015].

Inflammation

In patients with gout, MSUCs were found in 36/37 (97%) of knee joints with previous involvement but patients were asymptomatic and in 8/37 (22%) of never-affected joints. The presence of MSUCs was shown to be associated with low-grade inflammation as demonstrated by increased neutrophil counts in the synovial fluid [Pascual, 1991]. Therefore, the MSUCs are not as inert as supposed, even in the absence of clinical manifestations.

An increased power-Doppler signal in ultrasonography, a surrogate for increased vascularity of inflammation, was observed in 67% of 12 asymptomatic patients with MSUC deposition [Puig et al. 2008]. Nevertheless, in a controlled study, power-Doppler positivity was not observed either in hyperuricaemic or normouricaemic controls [Pineda et al. 2011].

There is robust epidemiological evidence of an association between hyperuricaemia and gout with vascular outcomes, probably related to increased risk of atherosclerosis [Krishnan et al. 2011]. Vascular outcomes such as myocardial infarction were associated with gout independently of the presence of hyperuricaemia [Krishnan et al. 2006]. Both high-level hyperuricaemia and deposition (as in patients with subcutaneous gout) are associated with increased mortality in patients with gout [Perez-Ruiz et al. 2014b], but high-level hyperuricaemia may also be associated with subclinical deposition. Recently, an association of ultrasonography detection of MSUC joint deposits with more severe coronary calcification in hyperuricaemic subjects with acute coronary syndrome has been reported [Andres et al. 2014]. Therefore, this raises the question of whether MSUC deposition and low-grade inflammation, among other plausible candidates, are determining factors contributing to vascular outcomes [Richette et al. 2014].

Structural damage

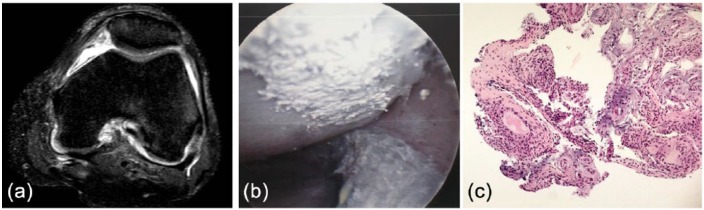

The structural damage in gout is related to the interaction between resident cells in the tissues where MSUCs deposit, both an innate and an adaptative immune response being present [Dalbeth et al. 2010]. The presence of MSUCs in the synovial membrane is associated with the development of chronic foreign body-like granulomas [Schumacher, 1975], similar to those observed in subcutaneous tophi [Dalbeth et al. 2010]. In addition, interaction between MSUCs and other cells such as osteoclasts [Dalbeth et al. 2008] osteoblasts [Chhana et al. 2011] or tenocytes [Chhana et al. 2014] may indicate that MSUCs are not inert crystalline structures and can induce cell responses. Chronic synovitis and deposition may be observed without any structural damage at the onset of symptoms, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

(a) Magnetic resonance imaging of the knee showing no deposition or structural damage at the first presentation of gout. (b) The patient underwent arthroscopy due to suspected infection, with urate deposits showing on the cartilage surface. (c) Synovial biopsy showing areas with chronic, foreign body-like granulomas. (reproduced from Perez-Ruiz et al. [2015] with permission).

Structural damage in gout is mainly evaluated using imaging techniques [Perez-Ruiz et al. 2009b]. Plain X-ray is not sensitive enough to detect early changes in patients with gout, namely bone erosions, compared with ultrasonography [Wright et al. 2006]. Erosions have been observed in a ultrasonographic study in 12% of asymptomatic hyperuricaemic patients versus 5.7% in normouricaemic controls, reported by the authors not to be significant, but further analysis of the frequency of erosions in subjects with and without deposition was unfortunately lacking, so no association between deposition and erosions can be ascertained [Pineda et al. 2011].

Erosions were observed with ultrasonography in 45% of 22 first metatarsophalangeal joints of patients with gout that were completely asymptomatic for such joints, and tophi were observed in 32% of them [Wright et al. 2006].

Increased deposition has been associated not only with erosions and structural damage, but also with a greater number and intensity of acute episodes of inflammation [Gutman, 1973], disability [Dalbeth et al. 2007b], loss of patients` perception of quality of life [Khanna et al. 2011], as well as increased healthcare resource use [Khanna et al. 2012b].

Clinical manifestations

As mentioned above, gout has been academically stratified into consecutive stages, namely acute gout, intercritical gout and chronic gout. This clinical staging is frequently found in clinical practice, but may be misleading in different ways [Perez-Ruiz et al. 2014a]. First, intercritical gout may be considered as an asymptomatic period with no underlying pathogenic process, such as inflammation or tissue damage, and therefore not requiring any therapeutic intervention [Doherty et al. 2012]. Second, the definition may imply that gout, a true deposition disease, is not a chronic condition because of absence of symptoms or apparent clinical manifestations. Lastly, patients presenting with clinical manifestations, considered therefore to be atypical, are not correctly classified and so are misdiagnosed [Perez-Ruiz et al. 2009a].

Untreated, persistent hyperuricaemia in patients with gout has been associated with increasing numbers of episodes of acute inflammation and development of polyarticular joint involvement distribution [Gutman, 1973].

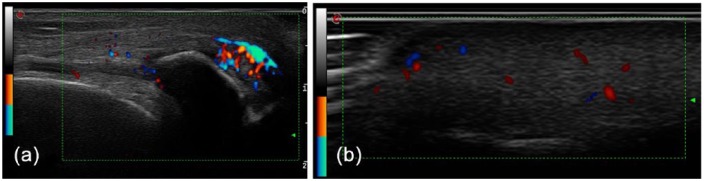

Despite our previous statements, it is not uncommon to observe extensive asymptomatic MSUC deposition in patients treated with corticosteroids [Vazquez-Mellado et al. 1999], as in the patient shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Ultrasonography of the knee (a) and finger pad (b) showing hyperechoic areas (tophi) with a power-Doppler signal in a patient with systemic lupus erythematosus treated with corticosteroids. No previous flare, but unspecific arthralgia was retrieved from careful anamnesis. The patient was fully asymptomatic after 6 months of intensive urate-lowering therapy. (reproduced from Perez-Ruiz et al. [2015] with permission).

Detecting deposition, inflammation and structural damage

Although clinical examination may give a sense of the presence of deposition (subcutaneous or periarticular tophi that may be palpated), structural damage (joint limitation and deformity), and inflammation (erythema, swelling or limitation), in clinical practice imaging is becoming the main source of information. This is especially true for early detection of MSUC deposition and subclinical structural damage and inflammation, as shown before. Three core domains for imaging in gout have been recently endorsed by the initia-tive Outcome Measures in Rheumatology (OMERACT): urate deposition (tophi), inflammation and structural damage [Grainger et al. 2015].

Radiographic scores have been used to evaluate structural damage in gout, but are only applied to patients with persistent, or chronic, clinical manifestations [Dalbeth et al. 2007b]. Increasing radiographic scores are associated with an increasing burden of intraosseous tophi [Dalbeth et al. 2009], which was shown half a century ago to be associated with time of exposure to untreated gout and increasing sUA [Gutman, 1973].

Ultrasonography is an office-based imaging technique used to evaluate MSUC deposition, as mentioned above. The double-contour sign (deposits in the articular surface of the hyaline cartilage) and hyperechoic areas surrounded by a hypoechoic halo (tophi) have been considered to be highly specific for gout in the hands of trained observers [Peiteado et al. 2012]. The main limitations to ultrasonography is that inter-observer reliability for the double-contour sign has been reported recently to be moderate (kappa 0.52) in a well-designed study [Naredo et al. 2013]. In addition, ultrasonography can capture structural damage (erosions and joint-space narrowing), synovial thickening (synovitis) and power-Doppler signal (active synovitis and peritophaceous inflammation) [Perez-Ruiz et al. 2009b]. It has also been shown to be sensitive to change during urate-lowering therapy [Perez-Ruiz et al. 2007]. Two different approaches have been studied: extensive ultrasonography scanning of cartilage, tendons and articular space for diagnosis [Naredo et al. 2013], and short (6 min) four-joint (first metatarsophalangeals and knees) ultrasonography scan [Peiteado et al. 2012], but both studies were performed in patients with longstanding gout in whom tophi were not uncommon.

Computed tomography (CT) is useful to evaluate structural damage compared with plain radiographs [Dalbeth et al. 2009]. Limitations include a lack of sensitivity in capturing deposition and inflammation. DECT is an imaging technique that has been shown to be highly specific and reproducible (as it is software based) in detecting MSUC deposits. Although the specificity of DECT is better than that of ultrasonography, the sensitivity of DECT does not seem to be better [Gruber et al. 2014], and ultrasonography performs best in detecting early deposits [Huppertz et al. 2014]. DECT, as CT, is not able to capture inflammation. Artefacts are a common false positive finding with DECT, especially around the nails or skin, but are easily recognized [Mallinson et al. 2014].Technical adjustment of the software has been considered to be a cause of false negative findings with DECT [McQueen et al. 2013]. Sensitivity to change during implementation of urate-lowering therapy has shown conflicting results [Choi et al. 2012; Rajan et al. 2013]. Digital tomosynthesis has recently been proposed as a low radiating, good quality, more feasible and inexpensive alternative to plain radiographs and CT [Dalbeth et al. 2014].

MRI is a multipurpose imaging technique that can evaluate bone, cartilage and soft tissue including tendons, ligaments, synovial membranes and nodules. It can also capture swelling, either in bone and soft tissue, and inflammation (if enhanced with gadolinium) [Perez-Ruiz et al. 2009b]. MRI 3 tesla can be especially useful in evaluating cartilage damage [Popovich et al. 2014], but studies have been limited to wrists.

Treating hyperuricaemia with deposition

As discussed in the introduction, the definition of gout itself may influence the prescription of ULMs as to whether they should only be considered in the presence of symptoms. We will discuss further whether clinical or imaging findings would be needed to consider intervention in patients with asymptomatic deposition. The presence of symptoms such as acute and chronic inflammation, evident tophaceous deposition on physical examination or evident X-ray structural damage are well accepted indications for urate-lowering intervention in guidelines and recommendations [Khanna et al. 2012a; Richette et al. 2014; Zhang et al. 2006); heretofore, the presence of subtle structural damage or small tophaceous deposits observed with imaging techniques still remains to be controversial as an indication for ULT .

Pros

Ultrasonography can be a useful, reliable and accurate office-based tool, compared with CT and DECT, to evaluate the amount and impact of deposits in joint structures. Ultrasonography-guided puncture may also enhance the achievement of gold-standard (observation of MSUCs in microscopy) diagnosis.

Early intervention on hyperuricaemia in patients with crystal-proved deposition, even if asymptomatic, could be considered and discussed with patients, when early structural damage, such as subclinical ultrasonographic findings of bone erosions, deposition shown as articular, nonpalpable tophi, and sound subclinical inflammation, as shown with power-Doppler signal, is present. These findings are not infrequent but present in a number of subjects with asymptomatic hyperuricaemia, what may be called asymptomatic gout or hyperuricaemia with deposition and the starting point for new therapeutic approaches [Perez-Ruiz and Punzi, 2015]. The rational use of colchicine, according to labels, recommendations and guidelines, and ULMs available, is associated with a low rate of serious adverse events [Jennings et al. 2014; Terkeltaub, 2009], and therefore could overweigh the risk of adverse events. Allopurinol initiation in patients with hyperuricaemia or gout has been shown to be associated with a modest reduction in mortality rate, the authors concluding that it probably outweighs the impact of adverse events [Dubreuil et al. 2014].

Evaluation of subclinical inflammation associated with MSUC deposits and the impact of intervention, either colchicine [Crittenden et al. 2012], or ULMs to deplete deposits, and therefore inflammation, could also be considered in patients with early demonstration of urate deposition and high risk for cardiovascular events [Grimaldi-Bensouda et al. 2014], or even chronic kidney disease [Goicoechea et al. 2010, 2015 ]. Targeting different mechanisms, such as hyperuricaemia, inflammation and xanthine oxidase has been proposed [Richette et al. 2014].

Cons

The first formal consideration is that the prescription of ULMs for asymptomatic hyperuricaemia is not widely approved, except in some countries such as Japan, and in certain situations, such as high cardiovascular risk or chronic kidney disease. The indication for hyperuricaemia with proved deposition even in the presence of mild structural damage has not yet been considered, and therefore not labelled.

In the second place, even sophisticated imaging techniques such as high-sensitivity ultrasonography and DECT have not been shown to be fully specific for urate deposition. Therefore, even in the theoretically optimal situation in which crystal-proved deposition is demonstrated associated with early structural damage and inflammation, there is no information available on the impact of such findings on further structural damage or the risk of appearance of meaningful clinical manifestations during the life expectancy of the subject.

In addition, medical errors in prescription and adherence to quality indicators are not infrequent [Mikuls et al. 2005, 2006] adverse events associated with increased rate of comorbid conditions [Franchi et al. 2014]; a systematic review of the allopurinol hypersensitivity syndrome has recently shown that 60% of patients did not have an approved indication for its prescription [Ramasamy et al. 2013], although prescription habits may greatly contribute to the risk of toxicity [Mikuls et al. 2005].

To the authors knowledge there is no definitive study, and a prospective one specifically designed for this purpose is much needed, on whether the impact of early intervention in patients with hyperuricaemia with true urate deposition on the natural history of gout, renal function and cardiovascular events would overweigh the risk of exposure to ULMs. This therefore remains an unanswered question to date.

Footnotes

Funding: This research has received a grant from Asociación de Reumatólogos del Hospital de Cruces.

Conflict of interest statement: FPR has been an adviser/speaker for AstraZeneca, Cymabay and Menarini, and received investigation funds from Ministerio de Sanidad, Gobierno de España, Departamento de Tecnología e Innovación, Gobierno Vasco, Fundación Española de Reumatología, and Asociación de Reumatólogos del Hospital de Cruces.

Contributor Information

Fernando Perez-Ruiz, Rheumatology Division, Hospital Universitario Cruces, OSI-EEC, Pza Cruces Sn, 48903 Baracaldo, Biscay, Spain.

Estibaliz Marimon, Medicine School, University of the Basque Country, Biscay, Spain.

Sandra P. Chinchilla, Rheumatology Division, Hospital Universitario Cruces, Biscay, Spain

References

- Andres M., Quintanilla M., Sivera F., Vela P., Ruiz-Nodar J. (2014) Asymptomatic deposit of monosodium urate crystals associates to a more severe coronary calcification in hyperuricemic patients with acute coronary syndrome. Arthritis Rheumatol 66: S365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bardin T., Richette P. (2014) Definition of hyperuricemia and gouty conditions. Curr Opin Rheumatol 26: 186–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker M., Ruoff G. (2010) What do I need to know about gout? J Fam Pract 59: S1–S8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chhana A., Callon K., Dray M., Pool B., Naot D., Gamble G., et al. (2014) Interactions between tenocytes and monosodium urate monohydrate crystals: implications for tendon involvement in gout. Ann Rheum Dis 73: 1737–1741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chhana A., Callon K., Pool B., Naot D., Watson M., Gamble G., et al. (2011) Monosodium urate monohydrate crystals inhibit osteablast viability and function: implications for the development of erosions in gout. Ann Rheum Dis doi: 10.1136/ard.2010.144744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi H., Burns L., Shojania K., Koenig N., Reid G., Abufayyah M., et al. (2012) Dual energy CT in gout: a prospective validation study. Ann Rheum Dis 71: 1466–1471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chowalloor P., Keen H. (2013) A systematic review of ultrasonography in gout and asymptomatic hyperuricaemia. Ann Rheum Dis doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-202301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crittenden D., Lehmann R., Schneck L., Keenan R., Shah B., Greenberg J., et al. (2012) Colchicine use is associated with decreased prevalence of myocardial infarction in patients with gout. J Rheumatol 39: 1458–1464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalbeth N., Clark B., Gregory K., Gamble G., Sheehan T., Doyle A., et al. (2009) Mechanisms of bone erosions in gout: a quantitative analysis using plain radiography and computed tomography. Ann Rheum Dis 68: 1290–1295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalbeth N., Clark B., McQueen F., Doyle A., Taylor W. (2007a) Validation of a radiographic damage index in chronic gout. Arthritis Rheum 57: 1067–1073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalbeth N., Collis J., Gregory K., Clark B., Robinson E., McQueen F. (2007b) Tophaceous joint disease strongly predicts hand function in patients with gout. Rheumatology (Oxford) 46: 1804–1807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalbeth N., Gao A., Roger M., Doyle A., McQueen F. (2014) Digital tomosynthesis for bone erosion scoring in gout: comparison with plain radiography and computed tomography. Rheumatology (Oxford) 53: 1712–1713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalbeth N., House M., Aati O., Tan P., Franklin C., Horne A., et al. (2015) Urate crystal deposition in asymptomatic hyperuricaemia and symptomatic gout: a dual energy CT study. Ann Rheum Dis 10.1136/annrheumdis-2014-206397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalbeth N., Pool B., Gamble G., Smith T., Callon K., McQueen F., et al. (2010) Cellular characterization of the gouty tophus. A quantitative analysis. Arthitis Rheum 62: 1549–1556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalbeth N., Smith T., Nicolson B., Clark B., Callon K., Naot D., et al. (2008) Enhanced osteoclastogenesis in patients with tophaceous gout. Urate crystals promote osteoclast development through interactions with stromal cells. Arthritis Rheum 58: 1854–1865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalbeth N., Stamp L. (2014) Hyperuricaemia and gout: time for a new staging system? Ann Rheum Dis 73: 1598–1600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Miguel E., Puig J., Castillo C., Peiteado D., Torres R., Martin-Mola E. (2011) Diagnosis of gout in patients with asymptomatic hyperuricaemia: a pilot ultrasound study. Ann Rheum Dis 71: 157–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doherty M., Jansen T., Nuki G., Pascual E., Perez-Ruiz F., Punzi L., et al. (2012) Gout: why is this curable disease so seldom cured? Ann Rheum Dis 71: 1765–1770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubreuil M., Zhu Y., Zhang Y., Seeger J., Lu N., Rho Y., et al. (2014) Allopurinol initiation and all-cause mortality in the general population. Ann Rheum Dis doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2014-205269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EMA. (2015) Adenuric. Summary of product characteristics. London: European Medicines Agency; http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/EPAR_-_Product_Information/human/000777/WC500021812.pdf [Google Scholar]

- FDA. (2015) Uloric. Full prescribing information. Silver Spring, MD: Food and Drug Administration; http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2012/021856s006lbl.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Franchi C., Salerno F., Conca A., Djade C., Tettamanti M., Pasina L., et al. (2014) Gout, allopurinol intake and clinical outcomes in the hospitalized multimorbid elderly. Eur J Intern Med 25: 847–852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goicoechea M., Garcia de Vinuesa S., Verdalles U., Verde E., Macias N., Santos A., et al. (2015) Allopurinol and progression of CKD and cardiovascular events: long-term follow-up of a randomized clinical trial. Am J Kidney Dis 65: 543–549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goicoechea M., Garcia de Vinuesa S., Verdalles U., Ruiz-Caro C., Ampuero J., Rincón A., et al. (2010) Effect of allopurinol in chronic kidney disease progression and cardiovascular risk. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 5: 1388–1393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grainger R., Dalbeth N., Keen H., Durcan L., Edwards N., Perez-Ruiz F., et al. (2015) Imaging as an outcome measure in gout studies: report from the OMERACT Gout Working Group. J Rheumatol doi: 10.3899/jrheum.141164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimaldi-Bensouda L., Alperovitch A., Aubrun E., Danchin N., Rossignol M., Abenhaim L., et al. (2014) Impact of allopurinol on risk of myocardial infarction. Ann Rheum Dis doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-202972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruber M., Bodner G., Rath E., Supp G., Weber M., Schueller-Weidekamm C. (2014) Dual-energy computed tomography compared with ultrasound in the diagnosis of gout. Rheumatology (Oxford) 53: 173–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutman A. (1973) The past four decades of progress in the knowledge of gout, with an assessment of the present status. Arthritis Rheum 16: 431–445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huppertz A., Hermann K., Diekhoff T., Wagner M., Hamm B., Schmidt W. (2014) Systemic staging for urate crystal deposits with dual-energy CT and ultrasound in patients with suspected gout. Rheumatol Int 34: 763–771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jennings C., Mackenzie I., Flynn R., Ford I., Nuki G., De Caterina R., et al. (2014) Up-titration of allopurinol in patients with gout. Semin Arthritis Rheum 44: 25–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khanna D., Fitzgerald J., Khanna P., Bae S., Singh M., Neogi T., et al. (2012a) 2012 American College of Rheumatology guidelines for management of gout. Part 1: Systematic nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic therapeutic approaches to hyperuricemia. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 64: 1431–1446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khanna P., Nuki G., Bardin T., Tausche A., Forsythe A., Goren A., et al. (2012b) Tophi and frequent gout flares are associated with impairments to quality of life, productivity, and increased healthcare resource use: results from a cross-sectional survey. Health Qual Life Outcomes 10: 117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khanna P., Perez-Ruiz F., Maranian P., Khanna D. (2011) Long-term therapy for chronic gout results in clinically important improvements in the health-related quality of life: short form-36 is responsive to change in chronic gout. Rheumatology (Oxford) 50: 740–745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishnan E., Backer J., Furst D., Schumacher H. (2006) Gout and the risk of acute myocardial infarction. Arthritis Rheum 54: 2688–2696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishnan E., Pandya B., Chung L., Dabbous O. (2011) Hyperuricemia and the risk for subclinical coronary atherosclerosis – data from a prospective observational cohort study. Arthritis Res Ther 31: R66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mallinson P., Coupal T., Reisinger C., Chou H., Munk P., Nicolaou S., et al. (2014) Artifacts in dual-energy CT gout protocol: a review of 50 suspected cases with an artifact identification guide. AJR Am J Roentgenol 203: W103–W109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McQueen F., Doyle A., Reeves Q., Gamble G., Dalbeth N. (2013) DECT urate deposits: now you see them, now you don’t. Ann Rheum Dis 72: 458–459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikuls T., Curits J., Allison J., Hicks R., Saag K. (2006) Medication errors with the use of allopurinol and colchicine: a retrospective study of a national, anonymous internet-accessible error reporting system. J Rheumatol 33: 562–566. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikuls T., Farrar J., Bilker W., Fernandes S., Saag K. (2005) Suboptimal physician adherence to quality indicators for the management of gout and asymptomatic hyperuricaemia: results from the UK General Practice Research Database (GPRD). Rheumatology (Oxford) 44: 1038–1042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naredo E., Uson J., Jimenez-Palop M., Martinez A., Vicente E., Brito E., et al. (2013) Ultrasound-detected musculoskeletal urate crystal deposition: which joints and what findings should be assessed for diagnosing gout? Ann Rheum Dis doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-203487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pascual E. (1991) Persistence of monosodium urate crystals and low-grade inflammation in synovial fluid of patients with untreated gout. Arthritis Rheum 34: 141–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peiteado D., de Miguel E., Villalba A., Ordóñez M., Castillo C., Martin-Mola E. (2012) Value of a short four-joint ultrasound test for gout diagnosis: a pilot study. Clin Exp Rheumatol 30: 830–837. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Ruiz F., Castillo E., Chinchilla S., Herrero-Beites A. (2014a) Clinical manifestations and diagnosis of gout. Rheum Dis Clin North Am 40: 193–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Ruiz F., Dalbeth N., Bardin T. (2015) A review of uric acid, crystal deposition disease, and gout. Adv Ther 32: 31–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Ruiz F., Martin I., Canteli B. (2007) Ultrasonographic measurement of tophi as an outcome measure for chronic gout. J Rheumatol 34: 1888–1893. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Ruiz F., Martinez-Indart L., Carmona L., Herrero-Beites A., Pijoan J., Krishnan E. (2014b) Tophaceous gout and high level of hyperuricaemia are both associated with increased risk of mortality in patients with gout. Ann Rheum Dis 73: 177–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Ruiz F., Punzi L. (2015) Hyperuricemia and tissue monourate deposits: prospective therapeutic considerations. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci 19: 1549–1552. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Ruiz F., Ruiz Lopez J., Herrero Beites A. (2009a) Influence of the natural history of disease on a previous diagnosis in patients with gout. Reumatol Clin 5: 248–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Ruiz F., Schlesinger N., Dalbeth N., Urresola A., De Miguel E. (2009b) Imaging of gout: findings and utility. Arthritis Res Ther 11: 232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pineda C., Amezcua-Guerra L., Solano C., Rodriguez-Henriquez P., Hernandez-Diaz C., Vargas A., et al. (2011) Joint and tendon subclinical involvement suggestive of gouty arthritis in asymptomatic hyperuricemia: an ultrasound controlled study. Arthritis Res Ther 13: R4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popovich I., Dalbeth N., Doyle A., Reeves Q., McQueen F. (2014) Exploring cartilage damage in gout using 3-T MRI: distribution and associations with joint inflammation and tophus deposition. Skeletal Radiol 43: 917–924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puig J., de Miguel E., Castillo M., Rocha A., Martinez M., Torres R. (2008) Asymptomatic hyperuricemia: impact of ultrasonography. Nucleosides Nucleotides Nucleic Acids 27: 592–595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajan A., Aati O., Kalluru R., Gamble G., Horne A., Doyle A., et al. (2013) Lack of change in urate deposition by dual-energy computed tomography among clinically stable patients with long-standing tophaceous gout: a prospective longitudinal study. Arthritis Res Ther 15: R160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramasamy S., Korb-Wells C., Kannangara D., Smith M., Wang N., Roberts D., et al. (2013) Allopurinol hypersensitivity: a systematic review of all published cases, 1950–2012. Drug Saf 36: 953–980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richette P., Doherty M., Pascual E., Barskova V., Becce F., Coyfish M., et al. (2014) Updated EULAR evidence-based recommendations for the management of gout. Ann Rheum Dis 73: 783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richette P., Perez-Ruiz F., Doherty M., Jansen T., Nuki G., Pascual E., et al. (2014) Improving cardiovascular and renal outcomes in gout: what should we target? Nat Rev Rheumatol doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2014.124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schumacher H. (1975) Pathology of the synovial membrane in gout. Light and electron microscopic studies. Arthritis Rheum 18: 771–782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terkeltaub R. (2009) Colchicine update: 2008. Semin Arthritis Rheum 38: 411–419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TGAeBS. (2015) Adenuric. Public summary. Woden, ACT: Therapeutic Goods Administration, Department of Health, Australian Government; https://www.ebs.tga.gov.au/servlet/xmlmillr6?dbid=ebs/PublicHTML/pdfStore.nsf&docid=205556&agid=%28PrintDetailsPublic%29&actionid=1 [Google Scholar]

- Vazquez-Mellado J., Cuan A., Magaña M., Pineda C., Cazarin J., Pacheco-Tena C., et al. (1999) Intradermal tophi in gout: a case-control study. J Rheumatol 26: 136–140. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright S., Filippucci E., McVeigh C., Grey A., McCarron M., Grassi W., et al. (2006) High resolution ultrasonography of the 1st metatarsal phalangeal joint in gout: a controlled study. Ann Rheum Dis 66: 859–864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W., Doherty M., Pascual E., Bardin T., Barskova V., Conagham P., Gerster J., et al. (2006) EULAR evidence based recommendations for gout. Part II. Management. Report of a Task Force of the EULAR Standing Committee for international clinical studies including therapeutics (ESCISIT). Ann Rheum Dis 65: 1312–1324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]