Abstract

Background

Self‐myofascial release (SMR) is a popular intervention used to enhance a client's myofascial mobility. Common tools include the foam roll and roller massager. Often these tools are used as part of a comprehensive program and are often recommended to the client to purchase and use at home. Currently, there are no systematic reviews that have appraised the effects of these tools on joint range of motion, muscle recovery, and performance.

Purpose

The purpose of this review was to critically appraise the current evidence and answer the following questions: (1) Does self‐myofascial release with a foam roll or roller‐massager improve joint range of motion (ROM) without effecting muscle performance? (2) After an intense bout of exercise, does self‐myofascial release with a foam roller or roller‐massager enhance post exercise muscle recovery and reduce delayed onset of muscle soreness (DOMS)? (3) Does self‐myofascial release with a foam roll or roller‐massager prior to activity affect muscle performance?

Methods

A search strategy was conducted, prior to April 2015, which included electronic databases and known journals. Included studies met the following criteria: 1) Peer reviewed, english language publications 2) Investigations that measured the effects of SMR using a foam roll or roller massager on joint ROM, acute muscle soreness, DOMS, and muscle performance 3) Investigations that compared an intervention program using a foam roll or roller massager to a control group 4) Investigations that compared two intervention programs using a foam roll or roller massager. The quality of manuscripts was assessed using the PEDro scale.

Results

A total of 14 articles met the inclusion criteria. SMR with a foam roll or roller massager appears to have short‐term effects on increasing joint ROM without negatively affecting muscle performance and may help attenuate decrements in muscle performance and DOMS after intense exercise. Short bouts of SMR prior to exercise do not appear to effect muscle performance.

Conclusion

The current literature measuring the effects of SMR is still emerging. The results of this analysis suggests that foam rolling and roller massage may be effective interventions for enhancing joint ROM and pre and post exercise muscle performance. However, due to the heterogeneity of methods among studies, there currently is no consensus on the optimal SMR program.

Level of Evidence

2c

Keywords: Massage, muscle, treatment

Introduction

Self‐myofascial release (SMR) is a popular intervention used by both rehabilitation and fitness professionals to enhance myofascial mobility. Common SMR tools include the foam roll and various types of roller massagers. Evidence exists that suggests these tools can enhance joint range of motion (ROM)1 and the recovery process by decreasing the effects of acute muscle soreness,2 delayed onset muscle soreness (DOMS),3 and post exercise muscle performance.4 Foam rollers and roller massage bars come in several sizes and foam densities (Figure 1). Commercial foam rolls are typically available in two sizes: standard (6 inch × 36 inch)2–8 and half size (6 inch × 18 inches).9 With foam rolling, the client uses their bodyweight to apply pressure to the soft tissues during the rolling motion. Roller massage bars also come in many shapes, materials, and sizes. One of the most common is a roller massage bar constructed of a solid plastic cylinder with a dense foam outer covering.1,10,11 The bar is often applied with the upper extremities to the target muscle. Pressure during the rolling action is determined by the force induced by the upper extremities. The tennis ball has also been considered a form of roller massage and has been studied in prior research.12

Figure 1.

Examples of self‐myofascial release tools: Foam roller (left) and roller massager (right).

For both athletes and active individuals, SMR is often used to enhance recovery and performance. Despite the popularity of SMR, the physiological effects are still being studied and no consensus exists regarding the optimal program for range of motion, recovery, and performance.12 Only two prior reviews have been published relating to myofascial therapies. Mauntel et al13 conducted a systematic review assessing the effectiveness of the various myofascial therapies such as trigger point therapy, positional release therapy, active release technique, and self‐myofascial release on joint range of motion, muscle force, and muscle activation. The authors appraised 10 studies and found that myofascial therapies, as a group, significantly improved ROM but produced no significant changes in muscle function following treatment.13 Schroder et al14 conducted a literature review assessing the effectiveness self‐myofascial release using a foam roll and roller massager for pre‐exercise and recovery. Inclusion criteria was randomized controlled trials. Nine studies were included and the authors found that SMR appears to have positive effects on ROM and soreness/fatigue following exercise.14 Despite these reported outcomes, it must be noted that the authors did not use an objective search strategy or grading of the quality of literature.

Currently, there are no systematic reviews that have specifically appraised the literature and reported the effects of SMR using a foam roll or roller massager on these parameters. This creates a gap in the translation from research to practice for clinicians and fitness professionals who use these tool and recommend these products to their clients. The purpose of this systematic review was to critically appraisal the current evidence and answer the following questions: (1) Does self‐myofascial release with a foam roll or roller‐massager improve joint range of motion without effecting muscle performance? (2) After an intense bout of exercise, does self‐myofascial release with a foam roller or roller‐massager enhance post exercise muscle recovery and reduce DOMS? (3) Does self‐myofascial release with a foam roll or roller‐massager prior to activity affect muscle performance?

Methods

Search Strategy

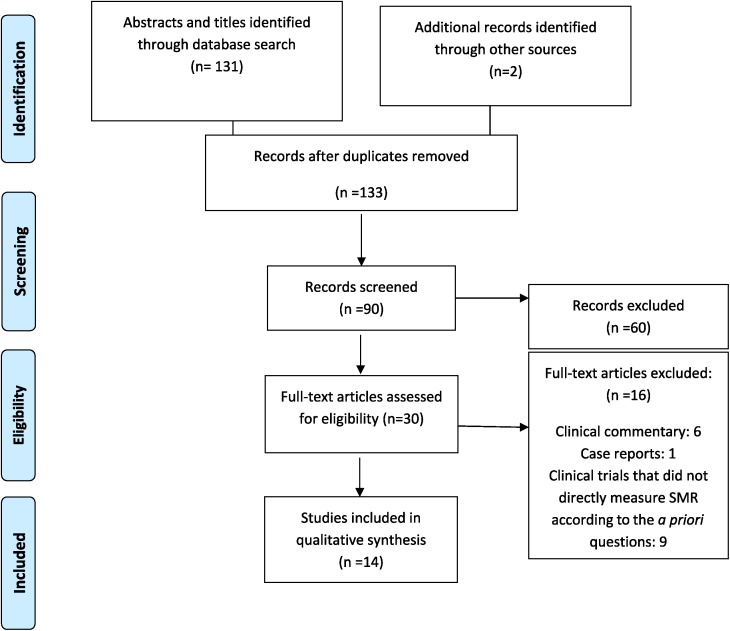

A systematic search strategy was conducted according the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta‐Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines for reporting systematic reviews (Figure 2).15,16 The following databases were searched prior to April 2015: PubMed, PEDro, Science Direct, and EBSCOhost. A direct search of known journals was also conducted to identify potential publications. The search terms included individual or a combination of the following: self; myofascial; release; foam roll; massage; roller; athletic; performance; muscle; strength; force production; range of motion; fatigue; delayed onset of muscle soreness. Self‐myofascial release was operationally defined as a self‐massage technique using a device such as a foam roll or roller massager.

Figure 2.

PRISMA Search Strategy

Study Selection

Two reviewers (MC and ML) independently searched the databases and selected studies. A third independent reviewer (SC) was available to resolve any disagreements. Studies considered for inclusion met the following criteria:1) Peer reviewed, english language publications 2) Investigations that measured the effects of SMR using a foam roll or roller massager on joint ROM, acute muscle soreness, DOMS, and muscle performance 3) Investigations that compared an intervention program using a foam roll or roller massager to a control group 4) Investigations that compared two intervention programs using a foam roll or roller massager. Studies were excluded if they were non‐english publications, clinical trials that included SMR as an intervention but did not directly measure its efficacy in relation to the specific questions, case reports, clinical commentary, dissertations, and conference posters or abstracts.

Data Extraction and Synthesis

The following data were extracted from each article: subject demographics, intervention type, intervention parameters, and outcomes. The research design of each study was also identified by the reviewers. Qualifying manuscripts were assessed using the PEDro (Physiotherapy Evidence Database) scale for appraising the quality of literature.15,16 Intra‐observer agreement was calculated using the Kappa statistic. For each qualifying studies, the levels of significance (p‐value) is provided in the results section for comparison and the effect size (r) is also provided or calculated from the mean, standard deviation, and sample sizes, when possible. Effect size of > 0.70 was considered strong, 0.41 to 0.70 was moderate, and < 0.40 was weak.17

Results

A total of 133 articles were initially identified from the search and 121 articles were excluded due to not meeting the inclusion criteria. A total of 14 articles met the inclusion criteria. Reasons for exclusion of manuscripts are outlined in Figure 2. The reviewers Kappa value for the 14 articles was 1.0 (perfect agreement). Table 1. Provides the PEDro score for each of the qualifying studies and Appendix 1 provide a more thorough description of each qualifying study.

Table 1.

PEDro scores for qualified studies

| Item 1 | Item 2 | Item 3 | Item 4 | Item 5 | Item 6 | Item 7 | Item 8 | Item 9 | Item 10 | Item 11 | Total Score | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Helperin et al | Y | N | N | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | 7 |

| MacDonald et al (2013) | Y | N | N | Y | N | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | 6 |

| Mohr et al | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | 8 |

| Sullivan et al | Y | N | N | Y | N | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | 6 |

| Bradbury et al | Y | N | N | Y | N | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | 6 |

| Grieve et al | Y | Y | N | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 8 |

| Peacock et al | Y | N | N | Y | N | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | 6 |

| Bushell et al | Y | N | N | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | 7 |

| Macdonald et al (2014) | Y | Y | N | Y | N | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | 7 |

| Jay et al | Y | Y | N | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 8 |

| Pearcey et al | Y | N | Y | Y | N | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | 7 |

| Skarbot et al. | Y | Y | N | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 8 |

| Healey et al | Y | N | N | Y | N | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | 6 |

| Mikesky et al | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | 10 |

Pedro Criteria: Item 1(Eligibility criteria), Item 2 ( Subjects randomly allocated), Item 3 ( Allocation concealed), Item 4 ( Intervention groups similar), Item 5 (subjects were blinded), Item 6 (Therapists administering therapy blinded), Item 7 (All assessors blinded), Item 8 ( At least 1 key outcome obtained from more than 85% of subjects initially allocated), Item 9 (All subjects received treatment or control intervention or an Intention‐to‐treat analysis performed), Item 10 (Between group comparison reported for a least on variable), Item 11 (study provides both point measures and measures of variability for at least one key outcome)

Study Characteristics

All qualifying manuscripts yielded a total of 260 healthy subjects (Male‐179, Female‐81) (mean 19.6 years ± 3.10, range 15‐34 years) with no major comorbidities that would have excluded them from testing. Eleven studies reported including recreationally active individuals (e.g. exercising at least 2‐3 days per week),1–4,7–12,18 one study included a range of subjects from recreational to highly active,5 one study included collegiate athletes,19 and one study included physically untrained individuals.20 Due to the methodological diversity among qualifying studies, a more descriptive results section is provided so the reader can understand the various interventions and measures that were used for each study. The qualifying studies will be group and analyzed according to the proposed questions.

Joint Range of Motion

Foam Roller

Five studies5,7–9,18 used a foam roller as the main tool and measured its effects on ROM. Of the aforementioned five studies, three5,8,18 reported using a 6 inch × 36 inch polyethylene foam roller and two studies7,9 reported using a 6 inch × 36 inch high density foam roll constructed out of a hollow PVC pipe and outer ethylene acetate foam. Two studies7,8 used a standard cadence for the foam roll interventions and all studies5,7–9,18 used the subject's bodyweight. All studies5,7–9,18 measured the immediate effects (within 10 minutes after the intervention) and several other post‐test time points. The SMR intervention period for all studies ranged from two to five sessions for 30 seconds to one minute.5,7,8,18

Foam Rolling: Hip ROM

Two studies5,8 measured hip ROM after a prescribed intervention of foam rolling. Bushell et al5 foam rolled the anterior thigh in the sagittal plane (length of the muscle) and measured hip extension ROM of subjects in the lunge position with video analysis and used the Global Perceived Effect Scale (GPES) as a secondary measure. Thirty one subjects were assigned to an experimental (N=16) or control (N=15) group and participated in three testing sessions that were held one week apart with pre‐test and immediate post‐test measures. The experimental group foam rolled for three, one‐minute bouts, with 30 second rests in between. There were no reported cadence guidelines for the intervention. The control group did not foam roll. The authors found a significant (p≤0.05, r=‐0.11) increase in hip extension ROM during the second session in the experimental group. However; hip extension measures returned to baseline values after one week. The authors also found higher GPE score in the intervention group.

Mohr et al8 measured the effects of foam rolling combined with static stretching on hip flexion ROM. The authors randomized subjects (N=40) into three groups: (1) foam rolling and static stretching, (2) foam rolling, (3) static stretching. The foam roll intervention consisted of rolling the hamstrings in the sagittal plane using the subjects bodyweight (three session of 1 minute) with a cadence of one second superior (towards ischial tuberosity) and one second inferior (towards popliteal fossa) using the subjects bodyweight. Static stretching of the hamstrings consisted of three sessions, held for one minute. Hip flexion ROM was measured immediately after each intervention in supine with an inclinometer. Upon completion of the study, the authors found that foam rolling combined with static stretching produced statistically significant increases (p=0.001, r=7.06) in hip flexion ROM. Also greater change in ROM was demonstrated when compared to static stretching (p=0.04, r=2.63) and foam rolling (p=0.006, r=1.81) alone.8

Foam Rolling: Sit and Reach

Peacock et al18 examined the effects of foam rolling along two different axes of the body combined with a dynamic warm‐up in male subjects (N=16). The authors examined two conditions: medio‐lateral foam rolling followed by a dynamic warm‐up and anteroposterior foam rolling followed by a dynamic warm‐up. All subjects served as their own controls and underwent the two conditions within 7‐days of each other. The foam rolling intervention consisted of rolling the posterior lumbopelvis (erector spinae, multifidus), gluteal muscles, hamstrings, calf region, quadriceps, and pectoral region along the two axes (1 session for 30 seconds per region) using the subjects bodyweight. There was no reported cadence guidelines for the foam roll intervention. The dynamic warm‐up consisted of a series of active body‐weight movements that focused on the major joints of the body (20 repetitions for each movement).18 Outcome measures included the sit and reach test and several other performance tests including the vertical jump, broad jump, shuttle run, and bench press immediately after the intervention. Foam rolling in the mediolateral axis had a significantly greater effect (p≤0.05, r=0.16) on increasing sit and reach scores than rolling in the anteroposterior axis with no other differences among the other tests.18

Foam Rolling: Knee ROM

MacDonald et al7 examined the effects of foam rolling on knee flexion ROM and neuromuscular activity of the quadriceps in male subjects (N=11). Subjects served as their own controls and were tested twice: once after two sessions of 1 minute foam rolling in the sagittal plane on the quadriceps from the anterior hip to patella (cadence of 3 to 4 times per minute), and additionally after no foam rolling (control). The outcome measures included knee flexion ROM, maximal voluntary contraction (MVC) of the quadriceps, and neuromuscular activity via electromyography (EMG). Subjects were measured for all the above parameters pre‐test, 2 minutes after the two conditions, and 10 minutes after. The authors found a significant increase (p<0.001, r=1.13) of 108 at 2 minutes post‐test and a significant increase (p<0.001, r=0.92) of 88 at 10 minutes post‐test of knee flexion ROM following foam rolling when compared to the control group. There were no significant differences in knee extensor force and neuromuscular activity among all conditions.7

Foam Rolling: Ankle ROM

Skarabot et al9 measured the effects of foam rolling and static stretching on ankle ROM in adolescent athletes (N = 5 female, 6 male). The authors randomized subjects into three groups (conditions): (1) foam rolling, (2) static stretching, and (3) foam roll and static stretching. The foam rolling intervention consisted of three sessions of 30 seconds rolling on the calf region while the static stretching intervention consisted of a single plantarflexor static stretch performed for three sets of 30 seconds. There were no reported cadence guidelines for the foam rolling intervention. The outcome measure was dorsiflexion ROM measured in the lunge position pre‐test, immediately post‐test, 10, 15, and 20 minutes post‐test. From pre‐test to immediately post‐test, static stretching increased ROM by 6.2% (p < 0.05, r=‐0.13) and foam rolling with static stretching increased ROM by 9.1% (p<0.05, r=‐0.27) but no increases were demonstrated for foam rolling alone. Post hoc testing revealed that foam rolling with static stretching was superior to foam rolling. All changes from the interventions lasted less than 10 minutes. 9

Roller Massage

Five studies1,10–12,19 qualified for this analysis that used some type of a roller massager as the main tool. Two studies1,10 reported using a mechanical device connected to a roller bar that created a standard force and cadence. Two studies11,19 reported using a commercial roller bar that was self‐administered by the subjects using an established pressure but no standard cadence. One study12 reported using a tennis ball as a self‐administered roller massager with no standard pressure or cadence. All studies measured the acute effects in which measurements were taken within 10 minutes after the intervention period along with other post‐test time points. The intervention period for all studies ranged from two to five sessions for five seconds to two minutes.1,10–12,19

Roller Massage: Ankle ROM

Halperin et al11 compared the effects of a roller massage bar versus static stretching on ankle dorsiflexion ROM and neuromuscular activity of the plantar flexors. The authors randomized subjects (N=14) into 3 groups: (1) foam rolling and static stretching, (2) foam rolling, (3) static stretching. The roller massage intervention consisted of the subjects using the roller bar to massage the plantar flexors for three sets of 30 seconds at a cadence of one second per roll (travel the length of the muscle in one second). The pressure applied was equivalent to 7/10 pain on a numeric pain rating scale. Subjects established this level prior to testing. The static stretching intervention consisted of a standing calf stretch for three sets of 30 seconds using the same discomfort level of 7/10 to gauge the stretch. The outcome measures included ankle dorsiflexion ROM, static single leg balance for 30 seconds, MVC of the plantar flexors, and neuromuscular activity via EMG. Measurements were taken pre‐test, immediate post‐test, and 10 minutes post‐test. Both the roller massage (p<0.05, r=0.26, 4%) and static stretching (p<0.05, r=0.27, 5.2%) increased ROM immediately and 10 minutes post‐test. The roller massage did show small improvements in muscle force relative to static stretching at 10 minutes post‐test. Significant effects were not found for balance, MVC, or EMG.

Roller Massage: Knee ROM

Bradbury‐Squires et al10 measured the effects of a roller massager intervention on knee joint ROM and neuromuscular activity of the quadriceps and hamstrings. Ten subjects experienced three randomized experimental conditions: (1) 5 repetitions of 20 seconds (2) 5 repetitions of 60 seconds, (3) no activity (control).10 The roller massage intervention was conducted by a constant pressure apparatus that applied a standard pressure (25% of body weight) through the roller bar to the quadriceps. Subjects sat upright in the apparatus and activity moved their body to allow the roller to travel up and down the quadriceps. The subjects rolled back and forth at a cadence of 30 beats per minute (BPM) on a metronome, which allowed a full cycle to be completed in four seconds (two seconds towards hip, two seconds towards patella). The main pre‐test, post‐test outcome measures included the visual analog scale (VAS) for pain, knee joint flexion ROM, MVC for knee extension, and EMG activity of the quadriceps and hamstrings during a lunge. The authors found a 10% increase in post‐intervention knee ROM at 20 seconds and a 16% increase at 60 seconds post‐intervention when compared to the control (p<0.05). There was a significant increase in knee ROM and neuromuscular efficiency (e.g. reduced EMG activity in quadriceps) during the lunge. There was no difference in VAS scores between the 20 and 60 second interventions.10

Roller Massage: Hip ROM

Mikesky et al19 measured the effects of a roller massager intervention on hip ROM and muscle performance measures. The authors recruited 30 subjects and measured the effects of three randomized interventions: (1) control, (2) placebo (mock non‐perceivable electrical stimulation), (3) SMR with roller massager. Testing was performed over three days in which one of the randomized interventions were introduced and lasted for two minutes. The roller massage intervention consisted of the subject rolling the hamstrings for two minutes with no set pressure or cadence. The outcome measures consisted of hip flexion AROM, vertical jump height, 20‐yard dash, and isokinetic knee extension strength.19 All outcomes were measured pre and immediately post the intervention. No acute improvements were seen in any of the outcome measures following the roller massager intervention.19

Roller Massage: Sit and Reach

Sullivan et al1 measured the effects of a roller massager intervention on lower extremity ROM and neuromuscular activity. The authors used a pre‐test, immediate post‐test comparison of 17 subjects (8 experimental, 9 control) using the sit and reach test to measure flexibility, MVC, and neuromuscular activity via EMG measures of the hamstrings.1 The roller massager intervention consisted of four trials (one set of 5 seconds, one set of 10 seconds, two sets of 5 seconds, 2 sets of 10 seconds) to the hamstrings using a constant pressure apparatus connected to the roller massage bar which is similar to the apparatus and procedure described in Bradbury‐Squires et al10 study. The apparatus was set at a constant pressure of (13 kg) and cadence (120 BPM). Testing was conducted over two days with two intervention sessions per day on opposing legs separated by a 30 minute rest period. The control group attended a third session that included the pre‐test and post‐test measures but no intervention. The use of a roller massager produced a 4.3% (p<0.0001) increase in sit and reach scores after the intervention periods of one and two sets of 5 seconds. There was a trend (p=0.069, r=0.21) for 10 seconds of rolling to increase ROM more than five seconds of rolling. There were no significant changes in MVC or EMG activity after the rolling intervention.1

Grieve et al12 conducted a study measuring the effects of roller massage to the plantar aspect of the foot using a tennis ball. The authors randomized 24 subjects to an experimental or control group. The roller massage (tennis ball) intervention consisted of one session of SMR to each foot for two minutes.12 There was no established pressure or cadence. The author measured pre‐test and immediate post‐test flexibility using the sit and reach test as the main outcome measure. Upon completion of the study, the authors found a significant increase (p=0.03, r=0.21) in post‐test sit and reach scores when compared to the control scores.12

Post‐Exercise Muscle Recovery and Reduction of DOMS

Three studies2,3,20 used an exercised induced muscle damage program followed by an SMR intervention and measured the effects of SMR on DOMS and muscle performance. Two studies2,3 used a custom foam roll made out of a polyvinyl chloride pipe (10.16 cm length, 0.5 cm width) surrounded by neoprene foam (1cm thick) and utilized the subject's own body weight using a standard cadence. One study20 used a commercial roller massage bar which was administered by the researchers using an established pressure and standard cadence. The intervention period for all studies ranged from 10 to 20 minutes.2,3,20

Foam Roller

Macdonald et al2 measured the effects of foam rolling as a recovery tool after exercise induced muscle damage. The authors randomized 20 male subjects to an experimental (foam roll) or control group. All subjects went through the same protocol which included an exercise induced muscle damage program consisting of 10 sets of 10 repetitions of the back squats (two minutes of rest between sets) at 60% of the subjects one repetition maximum (RM) and four post‐test data collection periods (post 0, post 24, post 48, post 72 hours).2 At each post‐test period, the experimental group used the foam roll for a 20 minute session. The subject's pain level was measured every 30 seconds and the amount of force placed on the foam roll was measured via a force plate under the foam roll. The foam roll intervention consisted of two 60 second bouts on the anterior, posterior, lateral, and medial thigh. The subjects used their own body weight with no standard cadence. The main outcome measures were thigh girth, muscle soreness using a numeric pain rating scale, knee ROM, MVC for knee extension, and neuromuscular activity measured via EMG.2 Foam rolling reduced subjects pain levels at all post‐test points while improving post‐test vertical jump height, muscle activation, and joint ROM in comparison with the control group.2

Pearcy et al3 measured the effects of foam rolling as a recovery tool after an intense bout of exercise. The authors recruited eight male subjects who served as their own control and were tested for two conditions: DOMS exercise protocol followed by foam rolling or no foam rolling. A four week period occurred between the two testing session. All subjects went through a similar DOMS protocol to that, utilized by Mac Donald et al,2 which included 10 sets of 10 repetitions of the back squats (two minutes of rest between sets) at 60% of the subject's one RM. For each post‐test period, subjects either foam rolled for a 20 minutes session (45 seconds, 15 second rest for each hip major muscle group) or did not foam roll. For foam rolling, the subjects used their own body weight with a cadence of 50 BPM. Measurements were taken pre‐test and then during four post‐test data collection periods (post 0, post 24, post 48, post 72).The main outcome measures were pressure pain threshold of the quadriceps using an algometer, 30m sprint speed, standing broad jump, and the T‐test.3 Foam rolling reduced subjects pain levels at all post treatment points (Cohen d range 0.59‐0.84) and improvements were noted in performance measures including sprint speed (Cohen d range 0.68‐0.77), broad jump (Cohen d range 0.48‐0.87), and T‐test scores (Cohen d range 0.54) in comparison with the control condition.3

Roller Massage

Jay et al20 measure the effects of roller massage as a recovery tool after exercise induced muscle damage to the hamstrings. The authors randomized 22 healthy untrained males into an experimental and control group. All subjects went through the same DOMS protocol, which included 10 sets or 10 repetitions of stiff‐legged deadlifts using a kettlebell, with a 30 second rest between sets. The roller massage intervention included one session of 10 minutes of massage in the sagittal plane to the hamstrings using “mild pressure” at a cadence of 1‐2 seconds per stroke by the examiner.20 The main outcome measures included the VAS for pain and pressure pain threshold measured by algometry. The sit and reach test was used as a secondary outcome measure. The outcomes were measured immediately post‐test, and 10, 30, and 60 minutes thereafter. The roller massage group demonstrated significantly (p<0.0001) decreased pain 10 minutes and increased (p=0.0007) pressure pain thresholds up to 30 minutes post intervention. However; there were no statistically significant differences when compared to the control group at 60 minutes post‐test. There was no significant difference (p=0.18) in ROM between groups.20

Muscle performance

Three studies4,18,19 qualified for this part of the analysis that measured the effects of self‐myofascial release prior to muscular performance testing using a standard size high density commercial foam roll4 , standard commercial foam roll18, and a commercial roller massager.19 The intervention for two studies4,18 began with a dynamic warm‐up consisting of a series of lower body movements prior to the foam rolling intervention that lasted for one session of 30 seconds on the each of the following regions: lumbopelvis and all hip regions (anterior, posterior, lateral, and medial). The subjects used their own body weight with no standard cadence.4,18 One study19 used a combined five minute warm‐up on a bike with the roller massager intervention which lasted for a period of one session for two minutes on the hamstrings.

Healey et al4 measured the effects of foam rolling on muscle performance when performed prior to activity. The authors randomized 26 subjects who underwent two test conditions. The first condition included a standard dynamic warm‐up followed by one session of SMR with the foam roll for 30 seconds on the following muscles: quadriceps, hamstrings, calves, latissimus dorsi, and the rhomboids. Subjects used their own weight and no standard cadence was used. The second condition included a dynamic warm‐up followed by a front planking exercise for three minutes. Subjects were used as their own controls and the two test sessions were completed on two days. The main outcome measures included pre‐test, post‐test muscle soreness, fatigue, and perceived exertion (Soreness on Palpation Rating Scale, Overall Fatigue Scale, Overall Soreness Scale, and Borg CR‐10) and performance of four athletic tests: isometric strength, vertical jump height, vertical jump for power, and the 5‐10‐5 shuttle run.4 No significant difference was seen between the foam rolling and planking conditions for all four athletic tests. There was significantly less (p<0.05, r=0.32) post treatment fatigue reported after foam rolling than the plank exercise.4

Peacock et al18 also examined the effects of foam rolling on muscle performance in addition to the sit and reach distance described in the prior section on joint ROM. The authors measured performance immediately after the intervention using several tests which included the vertical jump, broad jump, shuttle run, and bench press. There was no significant difference found between the mediolateral and anteroposterior axis foam rolling for all performance tests.18

Mikesky et al19 also measured the effects of a roller massager on muscle performance along with hip joint ROM which was described in the prior section. The authors measured vertical jump height, 20 yard dash, and isokinetic knee extension strength pretest and immediately post‐test the intervention.19 The use of the roller massager showed no acute improvements in all performance outcome measures.19

Discussion

The purpose of this systematic review was to appraise the current literature on the effects of SMR using a foam roll or roller massager. The authors sought to answer the following three questions regarding the effects of SMR on joint ROM, post‐exercise muscle recovery and reduction of DOMS, and muscle performance.

Does self‐myofascial release with a foam roll or roller‐massager improve joint range of motion without effecting muscle performance?

The research suggests that both foam rolling and the roller massage may offer short‐term benefits for increasing sit and reach scores and joint ROM at the hip, knee, and ankle without affecting muscle performance.5,7–9,18 These finding suggest that SMR using a foam roll for thirty seconds to one minute (2 to 5 sessions) or roller massager for five seconds to two minutes (2 to 5 sessions) may be beneficial for enhancing joint flexibility as a pre‐exercise warmup and cool down due to its short‐term benefits. Also, that SMR may have better effects when combined with static stretching after exercise.8,9 It has been postulated that ROM changes may be due to the altered viscoelastic and thixotropic property (gel‐like) of the fascia, increases in intramuscular temperate and blood flow due to friction of the foam roll, alterations in muscle‐spindle length or stretch perception, and the foam roller mechanically breaking down scar tissue and remobilizing fascia back to a gel‐like state.7,8,10

After an intense bout of exercise, does self‐myofascial release with a foam roller or roller‐massager enhance post exercise muscle recovery and reduce DOMS?

The research suggests that foam rolling and roller massage after high intensity exercise does attenuate decrements in lower extremity muscle performance and reduces perceived pain in subjects with a post exercise intervention period ranging from 10 to 20 minutes.2,3,20 Continued foam rolling (20 minutes per day) over 3 days may further decrease a patient's pain level and using a roller massager for 10 minutes may reduce pain up to 30 minutes. Clinicians may want to consider prescribing a post‐exercise SMR program for athletes who participate in high intensity exercise. It has been postulated that DOMS is primarily caused by changes in connective tissue properties and foam rolling or roller massage may have an influence on the damaged connective tissue rather than muscle tissue. This may explain the reduction in perceived pain with no apparent loss of muscle performance.7 Another postulated cause of enhanced recovery is that SMR increases blood flow thus enhances blood lactate removal, edema reduction, and oxygen delivery to the muscle.3

Does self‐myofascial release with a foam roll or roller‐massager prior to activity affect muscle performance?

The research suggests that short bouts of foam rolling (1 session for 30 seconds) or roller massage (1 session for 2 minutes) to the lower extremity prior to activity does not enhance or negatively affect muscle performance but may change the perception of fatigue.4,18,19 It's important to note that all SMR interventions were preceded with a dynamic‐warm‐up focusing on the lower body.4,18,19 Perhaps the foam roller or roller massagers’ influence on connective tissue rather than muscle tissue may explain the altered perception of pain without change in performance.7 The effects of foam rolling or roller massage for longer time periods has not been studied which needs to be considered for clinical practice.

Clinical Application

When considering the results of these studies for clinical practice four key points must be noted. First, the research measuring the effects of SMR on joint ROM, post‐exercise muscle recovery and reduction of DOMS, and muscle performance is still emerging. There is diversity among study protocols with different outcome measures and intervention parameters (e.g. treatment time, cadence, and pressure). Second, the types of foam and massage rollers used in the studies varied from commercial to custom made to mechanical devices attached to the rollers. It appears that higher density tools may have a stronger effect than softer density. Curran et al6 found that the higher density foam rolls produced more pressure to the target tissues during rolling than the typical commercial foam roll suggesting a potential benefit. Third, all studies found only short‐term benefits with changes dissipating as post‐test time went on. The long‐term efficacy of these interventions is still unknown. Fourth, the physiological mechanisms responsible for the reported findings in these studies are still unknown.

Limitations

It should be acknowledged that SMR using a foam roll or roller massager is an area of emerging research that has not reached its peak and this analysis is limited by the chosen specific questions and search criteria. The main limitations among qualifying studies were the small sample sizes, varied methods, and outcome measures which makes it difficult for a direct comparison and developing a consensus of the optimal program.

Conclusion

The results of this systematic review indicate that SMR using either foam rolling or roller massage may have short‐term effects of increasing joint ROM without decreasing muscle performance. Foam rolling and roller massage may also attenuate decrements in muscle performance and reduce perceived pain after an intense bout of exercise. Short bouts of foam rolling or roller massage prior to physical activity have no negative affect on muscle performance. However, due to the heterogeneity of methods among studies, there currently is no consensus on the optimal SMR intervention (treatment time, pressure, and cadence) using these tools. The current literature consists of randomized controlled trials (PEDRO score of 6 or greater), which provide good evidence, but there is currently not enough high quality evidence to draw any firm conclusions. Future research should focus on replication of methods and the utilization of larger sample sizes. The existing literature does provide some evidence for utility of methods in clinical practice but the limitations should be considered prior to integrating such methods.

Appendix 1.

Description of qualified studies

| Author | Type of Study | Subjects | Device | Target Region | Outcome Measures | SMR Intervention |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bushell et al | RCT | N=31 (12M,2F) Control (N=15) Intervention (N = 16) |

Foam roll | Anterior Thigh | Hip Extension ROM in Lunge Positon Global Perceived Effect Scale |

Type: Foam roll Duration: 1 minute Session:3 session (1 week apart) Cadence: None Force: Subject's bodyweight |

| Mohr et al | RCT | N = 40 M Stretching (N=10) Foam Roll (N = 10) Stretch and FR (N = 10) Control (N=10) |

Foam roll | Posterior Thigh | Hip Flexion ROM | Type: Foam roll Duration: 1 minute Session: 3 sessions Cadence: 1 second up and down Force: Subject's bodyweight |

| Peacock et al | Within subject design | N = 16 M | Foam roll | lumbopelvis gluteal muscles, hamstrings, calf region, quadriceps, and pectoral | Sit‐and‐Reach (ROM) Vertical Jump Broad Jump Shuttle Run Bench Press |

Type: Foam roll Duration: 30 seconds Session: 1 (per muscle group) Cadence: None Force: Subject's bodyweight |

| Macdonald et al (2014) | RCT | N = 11 M | Foam roll | Quadriceps | Knee flexion ROM MVC EMG |

Type: Foam roll Duration: 1 minute Session: 2 sessions Cadence: 3 to 4 times per minute (up/down) Force: Subject's bodyweight |

| Skarbot et al | RCT | N = 11 (6M, 5F) | Foam roll | Ankle | Ankle ROM | Type: Foam roll Duration: 30 seconds Session: 3 session Cadence: None Force: Subject's bodyweight |

| Helperin et al | RCT | N=14 (12M, 2F) | Roller massage | Ankle | Dorsiflexion ROM MVC EMG Balance |

Type: Roller massage Duration: 30 seconds Session: 3 sessions Cadence: 1 second per roll Force: pressure equal to 7/10 |

| Bradbury et al | RCT | N = 10M | Roller massage machine | Knee | Knee flexion ROM VAS MVC EMG |

Type: Roller massage Duration: 20 seconds, 60 seconds Session: 5 sets of each Cadence: 1 second per roll Force: Machine (25% of bodyweight) |

| Mikesky et al | RCT | N=30 (7M, 23F) | Roller massage | Hamstrings | Hip flexion ROM Vertical jump height 20 yard dash Isokinetic knee extension strength |

Type: Roller massage Duration: 2 minutes Session: 1 session Cadence: None Force: None |

| Sullivan et al | Within subject design | N = 17 (7 M, 10 F) | Roller massage machine | Hamstrings | Sit and reach EMG MVC (Isometric Force) |

Type: Roller massage Duration: 5, 10 seconds Session: 2 (5 seconds), 2 (10 seconds) Cadence: 120 BPM Force: Machine (13 kg) |

| Grieve et al | RCT | N = 24 (8 M, 16 F) | Tennis Ball | Plantar foot | Sit and reach | Type: Tennis ball Duration: 2 minutes Session: 1 Cadence: None Force: None |

| MacDonald et al (2013) | RCT | N = 20M (Control = 10 Experimental=10) |

Foam roll | anterior, posterior, lateral, and medial thigh | Knee ROM NPRS MVC EMG |

Type: Foam roll Duration: 20 minutes Session: 1 (post treatment) Cadence: None Force: Subject's bodyweight |

| Pearcey et al | Within subject design | N = 8 M | Foam roll | anterior, posterior, lateral, and medial thigh | Pressure pain threshold 30‐m sprint Standing broad‐jump T‐test |

Type: Foam roll Duration: 20 minutes Session: 1 (post treatment) Cadence: 50 BPM Force: Subject's bodyweight |

| Jay et al | RCT | N = 22 M | Roller massage | Hamstrings | VAS Pressure pain threshold Sit and reach |

Type: Roller massage Duration: 10 minutes Session: 1 session Cadence: 1‐2 seconds per roll Force: “Mild pressure” |

| Healey et al | RCT | N = 26 (13 M, 13 F) | Foam roll | Quadriceps, hamstrings, calves, latissimus dorsi, rhomboids | Palpation Rating Scale Overall Fatigue Scale Overall Soreness Scale Borg CR‐10 Isometric strength Vertical jump height Vertical jump 5‐10‐5 shuttle run |

Type: Foam roll Duration: 30 seconds Session: 1 session Cadence: None Force: Subjects bodyweight |

ROM‐ Range of motion

MVC‐ Maximum voluntary contraction

NPRS‐ Numeric Pain Rating Scale

EMG‐ Electromyography

VAS‐ Visual analog scale

References

- 1.Sullivan KM Silvey DB Button DC, et al. Roller‐massager application to the hamstrings increases sit‐and‐reach range of motion within five to ten seconds without performance impairments. Int J Sports Phys Ther. 2013;8(3):228‐236. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Macdonald GZ Button DC Drinkwater EJ, et al. Foam rolling as a recovery tool after an intense bout of physical activity. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2014;46(1):131‐142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pearcey GE Bradbury‐Squires DJ Kawamoto JE, et al. Foam rolling for delayed‐onset muscle soreness and recovery of dynamic performance measures. J Athl Train. 2015;50(1):5‐13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Healey KC Hatfield DL Blanpied P, et al. The effects of myofascial release with foam rolling on performance. J Strength Cond Res. 2014;28(1):61‐68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bushell JE Dawson SM Webster MM. Clinical Relevance of Foam Rolling on Hip Extension Angle in a Functional Lunge Position. J Strength Cond Res. 2015. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Curran PF Fiore RD Crisco JJ. A comparison of the pressure exerted on soft tissue by 2 myofascial rollers. J Sport Rehabil. 2008;17(4):432‐442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.MacDonald GZ Penney MD Mullaley ME, et al. An acute bout of self‐myofascial release increases range of motion without a subsequent decrease in muscle activation or force. J Strength Cond Res. 2013;27(3):812‐821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mohr AR Long BC Goad CL. Effect of foam rolling and static stretching on passive hip‐flexion range of motion. J Sport Rehabil. 2014;23(4):296‐299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Škarabot J Beardsley C Štirn I. Comparing the effects of self‐myofascial release with static stretching on ankle range‐of‐motion in adolescent athletes. Int J Sports Phys Ther. 2015; 10(2): 203‐212. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bradbury‐Squires DJ Noftall JC Sullivan KM, et al. Roller‐massager application to the quadriceps and knee‐joint range of motion and neuromuscular efficiency during a lunge. J Athl Train. 2015;50(2):133‐140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Halperin I Aboodarda SJ Button DC, et al. Roller massager improves range of motion of plantar flexor muscles without subsequent decreases in force parameters. Int J Sports Phys Ther. 2014;9(1):92‐102. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grieve R Goodwin F Alfaki M, et al. The immediate effect of bilateral self myofascial release on the plantar surface of the feet on hamstring and lumbar spine flexibility: A pilot randomised controlled trial. J Bodyw Mov Ther. 2014. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mauntel T CM Padua D. Effectiveness of myofascial release therapies on physical performance measurements: A systematic review. Athl Train Sports Health Care. 2014;6:189‐196. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schroeder AN Best TM. Is Self Myofascial release an effective preexercise and recovery strategyϿ. A literature review. Curr Sports Med Rep. 2015;14(3):200‐208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Alessandro L Douglas GA Jennifer T, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta‐analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: explanation and elaboration. BMJ. 2009;339‐342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moher D Liberati A Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta‐analyses: The PRISMA statement. Annals Int Med. 2009;151(4):264‐269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cohen J. A power primer. Psychol Bull. 1992;112(1):155‐159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Peacock CA Krein DD Antonio J, et al. Comparing acute bouts of sagittal plane progression foam rolling vs. frontal plane progression foam rolling. J Strength Cond Res. 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mikesky AE Bahamonde RE Stanton K, et al. Acute effects of the Stick on strength, power, and flexibility. J Strength Cond Res. 2002;16(3):446‐450. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jay K Sundstrup E Sondergaard SD, et al. Specific and cross over effects of massage for muscle soreness: randomized controlled trial. Int J Sports Phys Ther. 2014;9(1):82‐91. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]