Abstract

We report an integrated pipeline for efficient serum glycoprotein biomarker candidate discovery and qualification that may be used to facilitate cancer diagnosis and management. The discovery phase used semi-automated lectin magnetic bead array (LeMBA)-coupled tandem mass spectrometry with a dedicated data-housing and analysis pipeline; GlycoSelector (http://glycoselector.di.uq.edu.au). The qualification phase used lectin magnetic bead array-multiple reaction monitoring-mass spectrometry incorporating an interactive web-interface, Shiny mixOmics (http://mixomics-projects.di.uq.edu.au/Shiny), for univariate and multivariate statistical analysis. Relative quantitation was performed by referencing to a spiked-in glycoprotein, chicken ovalbumin. We applied this workflow to identify diagnostic biomarkers for esophageal adenocarcinoma (EAC), a life threatening malignancy with poor prognosis in the advanced setting. EAC develops from metaplastic condition Barrett's esophagus (BE). Currently diagnosis and monitoring of at-risk patients is through endoscopy and biopsy, which is expensive and requires hospital admission. Hence there is a clinical need for a noninvasive diagnostic biomarker of EAC. In total 89 patient samples from healthy controls, and patients with BE or EAC were screened in discovery and qualification stages. Of the 246 glycoforms measured in the qualification stage, 40 glycoforms (as measured by lectin affinity) qualified as candidate serum markers. The top candidate for distinguishing healthy from BE patients' group was Narcissus pseudonarcissus lectin (NPL)-reactive Apolipoprotein B-100 (p value = 0.0231; AUROC = 0.71); BE versus EAC, Aleuria aurantia lectin (AAL)-reactive complement component C9 (p value = 0.0001; AUROC = 0.85); healthy versus EAC, Erythroagglutinin Phaseolus vulgaris (EPHA)-reactive gelsolin (p value = 0.0014; AUROC = 0.80). A panel of 8 glycoforms showed an improved AUROC of 0.94 to discriminate EAC from BE. Two biomarker candidates were independently verified by lectin magnetic bead array-immunoblotting, confirming the validity of the relative quantitation approach. Thus, we have identified candidate biomarkers, which, following large-scale clinical evaluation, can be developed into diagnostic blood tests. A key feature of the pipeline is the potential for rapid translation of the candidate biomarkers to lectin-immunoassays.

Biomarkers play a central role in health care by enabling accurate diagnosis and prognosis; hence there is extensive research on the identification and development of novel biomarkers. However, despite numerous biomarker publications over the years (1), only a handful of new cancer biomarkers have successfully completed the journey from discovery, qualification, to verification and validation (2–4). One possible way to overcome this challenge is to develop an integrated biomarker pipeline that facilitates the smooth and successful transition from discovery to validation (5–10). The first and foremost consideration in an integrated pipeline is the sample source. In general, most of the proteomics based workflows use tissues or proximal fluids during the discovery phase, with the goal of extending the findings to plasma. Although this approach avoid the high complexity serum/plasma proteome and the associated requisite multi-dimensional sample separation in discovery stages, it often leads to failure when the candidates are not detected in plasma because of the limited sensitivity of the available analytical methods, or the absence of candidates in the plasma (11). To overcome this pitfall, we have developed an integrated glycoprotein biomarker pipeline, which can simply and rapidly isolate glycosylated proteins from serum to enable high throughput analysis of differentially glycosylated proteins in discovery and qualification stages.

The workflow utilizes naturally occurring glycan binding proteins, lectins, in a semi-automated high throughput workflow called lectin magnetic bead array-tandem mass spectrometry (LeMBA-MS/MS)1 (12, 13). Although lectins have been well-utilized in glycobiology and biomarker discovery (14–17), the LeMBA-MS/MS workflow demonstrates several unique features. First, serum glycoproteins are isolated in a single-step using 20 individual lectin-coated magnetic beads in microplate format. Second, we have optimized the concentrations of salts and detergents for sample denaturation to avoid co-isolation of protein complexes without adversely affecting lectin pull-down efficiency. Third, a liquid handler is used for sample processing to facilitate high-throughput screening and increase reproducibility. In addition, we have optimized on-bead trypsin digestion and incorporated lectin-exclusion lists during nano-LC-MS/MS to identify nonglycosylated peptides from the isolated glycoproteins. With these innovations, LeMBA-MS/MS demonstrates nanomolar sensitivity and linearity, and applicability across species (12). Compared with existing single, serial or multi-lectin affinity chromatography (18, 19), LeMBA-MS/MS offers the capability to simultaneously screen 20 lectins in a semi-automated, high throughput manner. On the other hand, because LeMBA-MS/MS identifies the nonglycosylated peptides, it cannot be used for glycan site assignment and glycan structure elucidation (20–23). However, the main advantage of LeMBA, we believe, is as a part of an integrated translational biomarker pipeline leading to lectin immunoassays. The lack of glycan structure details is not critical for clinical translation, as exemplified by the alpha-fetoprotein-L3 (AFP-L3) test, which measures the Lens culinaris agglutinin (LCA) binding fraction of serum alpha-fetoprotein (24, 25), and has been approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for detection of hepatocellular carcinoma.

In this study, we report the extension of the glycoprotein biomarker pipeline to the qualification phase with LeMBA-MRM-MS, and introduce statistical analysis pipelines GlycoSelector (http://glycoselector.di.uq.edu.au/) and Shiny mixOmics (http://mixomics-projects.di.uq.edu.au/Shiny) for the discovery and qualification phases, respectively. The utility of this integrated serum glycoprotein biomarker pipeline is demonstrated using esophageal adenocarcinoma (EAC) with unmet clinical need for an in vitro diagnostic test. EAC is a lethal malignancy of the lower esophagus with very poor 5-year survival rate of less than 25% (26). EAC is becoming increasingly common and its incidence is associated with the prevalent precursor metaplastic condition Barrett's esophagus (BE), but with a low annual conversion rate of up to 1% (27). A common set of risk factors are described for BE and EAC, include gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), obesity, male gender, and smoking (28, 29). The current endoscopy-biopsy based diagnosis is invasive and costly, leading to an ineffective surveillance program. A blood test employing serum biomarkers that can distinguish patients with EAC from those with either BE or healthy tissue would, potentially, change the paradigm for the way in which BE and EAC are managed in the population (30). Serum glycan profiling studies have shown differential expression of glycan structures between healthy, BE, early dysplastic and EAC patients (31–35). However, diagnostic serum glycoproteins showing differential glycosylation hence differential lectin binding remain to be discovered, making it a suitable disease model for this study.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Study Design and Sample Information

The overall biomarker study design was based on the strategy proposed by Rifai et al. (3), with the current work spanning discovery and qualification of the described four-phase paradigm. Serum samples were collected as part of the Australian Cancer Study (ACS) (36) and Study of Digestive Health (SDH) (37). All patients in these studies gave written, informed consent, and the studies were approved by the Human Research Ethics Committees of Queensland Institute for Medical Research, the University of Queensland, and all participating hospitals. Identical SOPs were followed for collecting samples for SDH and ACS, and processed by the same person. All 29 serum samples (Healthy-9, BE-10 and EAC-10) used for biomarker discovery phase and 79 serum samples (Healthy-20, BE-20, EAC-20 and population control-19) used for biomarker qualification study were matched by age; all selected patients were male considering the high male-dominance of EAC (29). The samples were stored at −80 °C until use. Healthy controls were individuals with no history of esophageal cancer and no evidence of esophageal histological abnormality at the time of endoscopic sample collection. BE patients had a histologically confirmed diagnosis of Barrett's mucosa. EAC patients had histologically confirmed adenocarcinoma within the distal esophagus or gastro-esophageal junction. EAC patient sera were collected prior to the commencement of cancer treatment. Population controls were volunteers with no self-reported history of EAC or BE. Samples were randomized prior to all experiments. Table I and II describes patient information used in this study. For categorical and numerical variables related to patient information, p values were calculated using Fisher's exact test and Kruskal-Wallis test respectively.

Table I. Clinical characteristics of the patient cohort for biomarker discovery. For categorical and numerical variables, p values were calculated using Fisher's exact test and Kruskal-Wallis test respectively.

| Variables | Healthy | BE | EAC | p value (Healthy vs BE vs EAC) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample size | 9 | 10 | 10 | |

| Age (Median ± S.D.) | 66 ± 10 | 62 ± 15 | 66 ± 8 | 0.9311 |

| Gender | All male | All male | All male | |

| Protein concentration (μg/μl) | 95 ± 19 | 85 ± 13 | 82 ± 13 | 0.3641 |

| Gastritisa | 1 (11.1%) | 1 (11.1%) | 1 (10.0%) | 1.0000 |

| Peptic ulcer | 3 (33.3%) | 2 (20.0%) | 3 (30.0%) | 0.8792 |

| Hiatus hernia | 0 (0.0%) | 4 (40.0%) | 6 (60.0%) | 0.0217 |

| Other malignancy | 1 (11.1%) | 2 (20.0%) | 2 (20.0%) | 1.0000 |

a All the analyses were performed based on available patient information. Gastritis status for one BE patient was missing.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

MyOneTM Tosyl activated Dynabeads were from Life Technologies. Lectins AAL, BPL, DSA, EPHA, GNL, JAC, LPHA, MAA, NPL, SNA, STL, and UEA were from Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA. Modified sequencing grade trypsin was from Promega, Madison, WI. Protein assay Bradford reagent, Triton X-100, and sodium dodecyl sulfate solution were from Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA. Tris base, glycine, sodium chloride, and acrylamide/bis-acrylamide solution 40% 29:1 were from Amresco, Solon, OH. Glycerol, disodium hydrogen phosphate dihydrate, sodium dihydrogen phosphate dihydrate, calcium chloride dehydrate, and Tween-20 were from Ajax Finechem, NSW, Australia. Magnesium chloride and manganese chloride were from Univar. For quadrupole time of flight runs, acetonitrile, isocratic HPLC grade was from Scharlau and for triple quadrupole runs, acetonitrile CHROMASOLV® gradient grade was from Sigma, St. Louis, MO. Heavy labeled stable isotope-labeled standard (SIS) peptides were from Sigma. All other reagents including lectins not listed above were from Sigma unless otherwise specified.

Serum Glycoprotein Biomarker Discovery and Qualification Pipeline

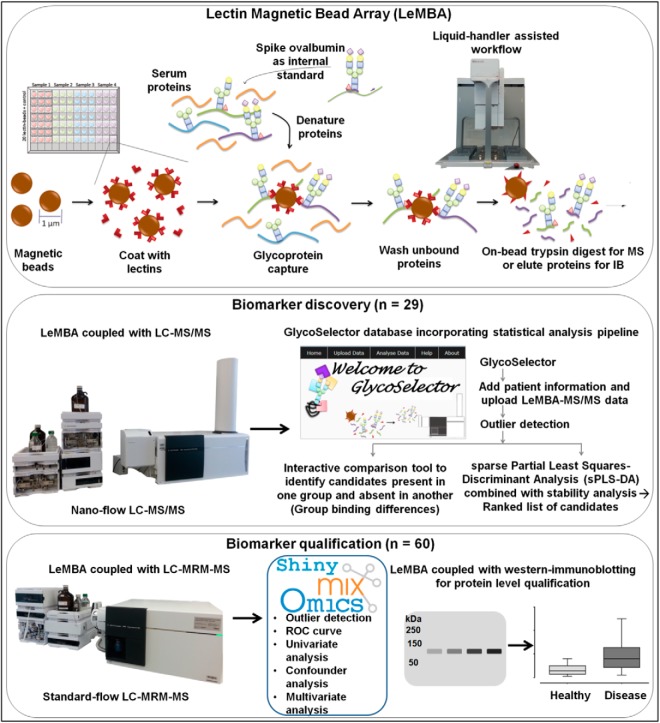

Fig. 1 represents the integrated glycoprotein biomarker discovery and qualification pipeline developed using LeMBA. The discovery phase aimed to identify changes in the lectin binding of medium to high abundance serum proteins that can distinguish between different phenotypes. To enable economic and high throughput label-free quantitation while controlling for sample processing, including tryptic digestion, we employed a nonlabeled spiked-in glycoprotein standard at the very first step of the workflow prior to denaturation (Fig. 1). Pilot experiments identified chicken ovalbumin as a suitable internal standard, with low homology to species of interest (human or mouse) that bound to all 20 lectins experimentally. Optimization experiments determined that 10 picomole ovalbumin to be added to each sample (50 μg of serum) per lectin pull-down. Depending upon the individual lectin, between 3 and 5 ovalbumin peptides (out of 7) were used for normalization (supplemental Table S1). Details about the data normalization and statistical analyses platforms GlycoSelector and Shiny mixOmics can be found in Supplemental Methods.

Fig. 1.

Generalized workflow schematic for serum glycoprotein biomarker discovery and qualification. Serum samples from respective patient groups were enriched for sub-glycoproteomes using 20 individual lectin coated magnetic beads, followed by on-bead trypsin digest and tandem mass spectrometry for label-free quantitation referencing to internal standard chicken ovalbumin. In-house database and statistical analysis pipeline ”GlycoSelector“ (http://glycoselector.di.uq.edu.au/) identified lectin–protein pairs present in one patient group and absent in the other. Sparse partial least squares-discriminant analysis (sPLS-DA) combined with stability analysis was used to generate ranked lists of lectin–protein candidates. For biomarker qualification, selected candidates were measured using multiple reaction monitoring-mass spectrometry (MRM-MS) in an independent patient cohort for a subgroup of lectin pull-downs. Dedicated statistical analysis tool ”Shiny mixOmics“ (http://mixomics-projects.di.uq.edu.au/Shiny) was developed incorporating tools to plot receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve and to perform univariate/multivariate statistical analyses. LeMBA-immunoblotting (IB) was used as an orthogonal method to verify peptide level MS data for selected candidates at the protein level.

Briefly, for discovery data, two different normalization approaches (1) based upon total ovalbumin protein intensity or (2) using individual ovalbumin peptide intensity were evaluated (supplemental Fig. S1A). There was a strong correlation between the two normalization approaches (supplemental Fig. S1B), and we selected the second normalization method for the pipeline as it gave equal weighting to each peptide. For each patient sample in discovery stage, a two-dimensional data set was generated, consisting of normalized intensity for proteins identified with each of the 20 lectin pull-down procedures. In general, glycoproteins bound several lectins, reflecting heterogeneity and multiplicity of glycosylation. GlycoSelector is a customized database with an incorporated statistical analysis pipeline coded in the R statistical programming language (38) and integrated in PHP server-side scripting language. The pipeline is based on tools developed in mixOmics (39), an R package dedicated to multivariate statistical analysis of “omics” data, and includes several steps such as data normalization, sample outlier detection, multivariate statistical analysis and group binding analyses. The sample outlier detection step aims to identify possible errors in sample handling/processing (supplemental Fig. S2). As an example of its utility, sample run ID 63 shown in supplemental Fig. S2A to S2D was considered to be an outlier because of consistent anomalous results detected in all four graphical outputs. The error was at the mass spectrometry step, because when the sample was re-run after mass spectrometer re-calibration, it was no longer detected as an outlier (supplemental Fig. S2E to S2H). To determine changes in the lectin binding of individual proteins between the different conditions, GlycoSelector was designed with two parallel approaches. Firstly, Group Binding Difference analyses were performed to identify on-off changes. In addition, multivariate statistical analysis based on sparse partial least square-discriminant analysis (sPLS-DA) (40) coupled with stability analysis was used to identify qualitative changes, after the exclusion of common contaminant proteins (supplemental Table S3).

Based on GlycoSelector analysis, a subset of 6 lectins and 41 glycoprotein candidates were selected for independent qualification (Fig. 1). The steps included, (1) MRM-MS assay development including confirmation of linearity and reproducibility, (2) screening an independent cohort of patient samples using customized LeMBA-MRM-MS, (3) two-step data normalization (supplemental Fig. S1A and supplemental Methods), and (4) univariate and multivariate statistical analysis using Shiny mixOmics.

Lectin Magnetic Bead Array (LeMBA)

LeMBA was performed as previously reported (12, 13) with modifications detailed in supplemental Methods section.

LC-MS/MS and Database Search for Biomarker Discovery

The LeMBA pull-down samples were resuspended in 20 μl of 0.1% v/v formic acid for LC-MS/MS (Agilent 6520 quadrupole time of flight (QTOF) coupled with a Chip Cube and 1200 HPLC). Initial experiments were performed to determine the optimal amount of tryptic peptides for LC-MS/MS: 9 μl were loaded for HAA, HPA, and UEA, 6 μl for NPL, STL, GNL, 5 μl for BPL, DSA, ECA, MAA, SBA, WFA, and WGA, 4 μl for AAL, SNA, LPHA, PSA, and JAC, 1 μl for EPHA and ConA. The nano pump was set at 0.3 μl/min and the capillary pump at 4 μl/min. The HPLC-chip used contains 160 nl C18 trapping column, and 75 μm × 150 mm 300 Å C18 analytical column (G4240–62010 Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA). Buffer A was 0.1% v/v formic acid and Buffer B was 90% v/v acetonitrile containing 0.1% v/v formic acid. Peptides were eluted from the column using a gradient from 6% B to 46% B at 45 min. Nano pump %B was increased to 95%B at 45.5 min and plateaued till 55.5 min, then decreased to 6% B at 58.5 min. The mass spectrometer was operated in 2 GHz extended dynamic range and programmed to acquire 8 precursor MS1 spectra per second and 4 MS/MS spectra for each MS1 spectra. Dynamic exclusion was applied after 2 MS/MS within 0.25 min. Exclusion for lectin peptides was applied as reported previously (12). The QTOF was tuned and calibrated prior to analysis. One hundred femtomole/μl of predigested bovine serum albumin peptides were used as quality control, before and after each plate. Levels of reference ions 299.2945 and 1221.9906 were maintained at minimum 5000 and 1000 counts respectively.

The raw data was extracted and searched using Spectrum Mill MS proteomics workbench (Agilent Technologies, Rev.B.04.00.127) against Swissprot human database containing 20,242 entries (release 3rd Jan 2012). Similar MS/MS spectra acquired on the precursor m/z within ± 1.4 m/z and within ± 15 s were merged. The following parameters were used for the search: Trypsin for digestion of proteins, 2 maximum missed cleavages, minimum matched peak intensity of 50%, precursor mass tolerance of ± 20 ppm, product mass tolerance of ± 50 ppm, calculate reversed database scores enabled and dynamic peak thresholding enabled. Carbamidomethylation was selected as fixed modification and oxidized methionine was selected as a variable modification. Precursor mass shift range from −17.0 Da to 177.0 Da was allowed for variable modification. Results were filtered by protein score > 15, peptide score > 6, and % scored peak intensity (% SPI) > 60. Automatic validation was used to validate proteins and peptides with default settings and false discovery rates (FDRs) were calculated using reversed hits.

BE-EAC Biomarker Qualification Using LeMBA-MRM-MS

Multiple reaction monitoring-mass spectrometry (MRM-MS) assay was performed on Agilent Technologies 6490 triple quadrupole mass spectrometer coupled with 1290 standard-flow infinity UHPLC fitted with a standard-flow ESI (Jet Stream) source to qualify candidate proteins for customized list of six lectin pull-downs (AAL, EPHA, JAC, NPL, PSA, and WGA) in an independent patient cohort. LeMBA was performed as described in Supplemental Methods. During MRM method development and validation stages, LeMBA pull-down of multiple lectins was combined and injected.

Protein, Peptide, and Transition Selection for MRM Method Development

Proteins identified using GlycoSelector with either of the above six lectins were selected for qualification. In addition, a few other proteins that were identified as candidate biomarkers with other lectins were also included for qualification.

MRM selector function of Spectrum Mill was used to retrieve the top ten peptides per protein for MRM method development, using several runs from the LeMBA-QTOF discovery data set. The parameters specified included 10 peptides per protein with a score of above 10 and % score peak intensity of 70%. The top four product y-ions for each precursor ion greater than precursor m/z were selected for MRM method development. The formula Collision energy (CE) = 0.036 m/z −4.8 was used to calculate CE for each precursor. Multiple MRM methods consisting of maximum 200 transitions were created as a first step of method development. All methods were transferred across to Skyline software version 2.1.0.4936 (http://skyline.maccosslab.org/) for visualization, subsequent method refinement and analysis (41). Using LeMBA-MS/MS discovery data (.mzxml and .pepxml files), a reference spectral library was built in Skyline. This reference library was used to compare the peptide fragmentation pattern in the MRM method as compared with QTOF data, and also to rank transitions. LeMBA pull-down from each of the 6 lectins was combined and run for each method to identify best MRM transitions. Each method incorporated transitions for internal standard chicken ovalbumin. Retention time prediction calculator iRT-C18 of Skyline was used to increase confidence of peptide identification (42). iRT scale was calibrated using the known retention time of the peptides and based on this calibration plot, retention time for the peptide of interest was predicted. MRM transitions showing good response at the correct retention time without any interference were selected for the next step. After the first round of method development, three MRM methods were created and each of these methods was run three times to find transitions showing stable responses. Some product y-ions (greater than precursor m/z) showed considerably low response. So to find out transition with higher response, up to five b- and y-ions less than precursor m/z were tried. Only transitions showing stable response during multiple runs were selected. Using retention time information for each peptide, one final dynamic MRM method was created incorporating a total of 145 peptides and 465 transitions with delta retention times of 2.5, 3 or 4 min, to quantify 41 proteins. supplemental Table S6 contains a detailed list of transitions used in the method.

LC Method Development

The UHPLC system consisted of a reverse phase chromatographic column AdvanceBio Peptide Mapping (150 × 2.1 mm i.d., 2.7 μm, part number 653750–902, Agilent Technologies) with a 5 mm long guard column. Mobile phase A consisted of 0.1% formic acid, and mobile phase B consisted of 100% acetonitrile and 0.1% formic acid. The UHPLC system was operated at 60 °C, with a flow rate of 0.4 ml/min. The gradient used for peptide separation was as follows: 3% B at 0 min; 30% B at 20 min; 40% B at 24 min; 95% B at 24.5 min; 95% B at 28.5 min; 3% B at 29 min; followed by conditioning of columns for 5 min at 3% B before injecting the next sample.

Mass Spectrometer Settings

Agilent 6490 triple quadrupole mass spectrometer was operated in positive ion mode and controlled by Agilent's MassHunter Work station software (version B.06.00 build 6.0.6025.4 SP4). The MRM acquisition parameters were 150 V high pressure RF, 60 V low pressure RF, 4000 V capillary voltage, 300 V nozzle voltage, 11 L/min sheath gas flow at a temperature of 250 °C, 15 L/min drying gas flow at a temperature of 250 °C, 30 psi nebulizer gas flow, unit resolution (0.7 Da full width at half maximum in the first quadrupole (Q1) and the third quadrupole (Q3), and 200 V delta EMV (+).

Loading Capacity Determination

Loading capacity for individual lectin pull-down was determined by injecting varying amounts of LeMBA pull-down and monitoring peptide responses using MRM-MS assay. Each LeMBA pull-down sample was resuspended in 20 μl 0.1% formic acid. 10 μl of this reconstituted sample was mixed with 6 μl SIS peptide mixture containing 150 femtomole of ISQAVHAAHAEINEAGR and VASMASEK each, 300 femtomole of VTSIQDWVQK, and 30 femtomole of AVEVLPK. Out of the total 16 μl mixture, the optimized loading for AAL, JAC, NPL and PSA lectin was 13 μl, EPHA lectin was 11.5 μl and WGA lectin was 12.5 μl.

Linearity and Reproducibility of MRM-MS

Linearity of the MRM-MS method was determined by injecting varying concentrations of aforementioned four SIS peptides spiked-into combined LeMBA pull-down sample of multiple lectins. The amount of SIS peptide spiked-in for each of four peptides was adjusted in such a manner that the response from the 1X labeled peptide mix fell within a 5-fold range of the cognate natural peptide. The concentration of spiked-in SIS peptide varied from 0.008× to 25× covering 3125-fold linear range where 1× concentration indicates mixture of 150 femtomole of ISQAVHAAHAEINEAGR and VASMASEK each, 300 femtomole of VTSIQDWVQK, and 30 femtomole of AVEVLPK. All dilutions were run in triplicate on each day for three consecutive days (n = 9). The ratio of SIS peptide response/natural peptide response was plotted.

Reproducibility of MRM-MS assay was determined by injecting combined LeMBA pull-down sample from the 6 lectins in quadruplicate on each day for four consecutive days (n = 16). This experiment also determined the stability of the sample resuspended in 0.1% formic acid under the storage condition in the auto sampler. It was anticipated that once samples were resuspended in 96 well plates, they would be run within 3 days. Hence reproducibility was checked for four consecutive days after reconstituting samples. Percent coefficient of variation (% CV) between runs was calculated using peptide responses normalized with respect to ovalbumin peptide.

Screening Samples for LeMBA-MRM-MS Qualification

Lectin-beads sufficient for biomarker qualification experiments were made in a single batch to minimize experimental variation. Serum samples were randomized for LeMBA-MRM-MS experiments. % CV of the entire LeMBA-MRM-MS screen was calculated based on response of heavy labeled SIS peptides and internal standard natural chicken ovalbumin peptides. All three SIS peptides, except methionine containing heavy labeled peptides, showed a % CV of less than 20% whereas % CV for normalized intensity of natural internal standard ovalbumin peptide was around or below 20% (supplemental Table S8), suggesting robustness (43) of the LeMBA pull-down and mass spectrometric measurement. Interestingly, normalized intensity of natural methionine containing peptide VASMASEK showed less variation as compared with nonnormalized intensity, suggesting SIS peptide VASMASEK containing methionine was able to correct for batch effects in methionine oxidation. One hundred femtomole of synthetic peptides mixture (G2455–85001, Agilent technologies) containing seven different human serum albumin peptides was run regularly to check linearity and reproducibility of the mass spectrometer results. When necessary, the mass spectrometer was tuned and calibrated.

Data Processing

Raw data from MRM-MS experiment was processed using Skyline. All peaks were manually checked for correct integration, and peak area for each peptide (sum of all transitions) was exported for further analysis. For linearity experiments, the ratio of SIS:Natural peptide was calculated and plotted against SIS peptide spiked-in concentration. Median normalization was performed for each lectin data set separately (supplemental Fig. S1A). Natural ovalbumin peptide peak intensity was first normalized with respective SIS labeled ovalbumin peptides. Next, using normalized intensity of natural ovalbumin peptide, the intensity of all other peptides was normalized. Methionine and nonmethionine containing peptides were dealt with separately during normalization steps, to account for batch effects in methionine oxidation. For reproducibility experiments, the normalized response with respect to ovalbumin peptide was calculated for each run, and the % CV of 16 injections of the same sample run over a period of 4 days calculated. Detailed statistical analysis was performed using normalized peptide intensity in the computing environment R. supplemental Table S7 contains normalized intensity of LeMBA-MRM-MS data.

Biomarker Qualification at Protein Level Using LeMBA-western Immunoblotting

The top two candidates AAL-HP and AAL-GSN, identified using sPLS-DA/stability analysis and the on/off change function of GlycoSelector, respectively, were verified using LeMBA-western immunoblotting in two sets of patient cohorts, firstly using serum samples from the same patients used for the discovery phase, and secondly using an independent set of 60 serum samples used for qualification. After AAL lectin pull-down, beads were directly boiled in 2× Laemmli sample buffer to elute captured glycoproteins. The denatured samples were separated by SDS-PAGE and proteins were transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (Millipore) using wet transfer. To compare results across membranes, an AAL pull-down sample from one healthy volunteer serum (unrelated to samples used in screen) was loaded in equal amounts on all gels. Membranes were blocked with 5% bovine serum albumin (BSA) in Tris-buffered saline-0.1% Tween-20 (TBST) for 1 h, and then carefully cut into two halves. The upper part of the membrane was incubated overnight with anti-gelsolin antibody (Epitomics #EP1940Y; 1: 3000 dilution in 5% BSA/TBST), whereas the lower portion was incubated with anti-haptoglobin antibody (Gen Way Biotech #GWB-16A7EA; 1: 1000 dilution in 5% BSA/TBST) at 4 °C overnight. This was followed by three TBST washes and incubation with 1: 3000 dilution of HRP-labeled anti-rabbit secondary antibody for 1 h at room temperature (Invitrogen #A10547). The blots were developed using SuperSignal West Pico chemiluminescence (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA), and captured on film (Fuji film, Tokyo, Japan; Developer and fixer solutions were from Kodak, Rochester, NY). Densitometric analysis was performed using ImageJ (NIH) (44). Raw densitometric values were normalized using the internal control sample loaded onto each gel.

Analysis for Confounders

To check the impact of confounding covariates (reflux frequency, body mass index (BMI), smoking, and alcohol consumption) on biomarker candidates, an additional 19 population control (electoral roll) serum samples were measured using LeMBA-MRM-MS, to achieve sufficient number of disease-free samples for statistical analysis. Healthy and population control sample groups were merged and categorized according to reflux frequency, BMI, cumulative smoking history and alcohol consumption. Kruskal-Wallis test was applied to all the qualified candidates for each confounding factor. Candidates that showed p < 0.05 for BMI, reflux, cumulative smoking history or alcohol consumption were considered as false positives and removed prior to multivariate analysis.

Functional Annotation Analysis

A list of candidates that differentiated EAC from BE was determined based on univariate Kruskal-Wallis test (p < 0.05) or multivariate analysis using sPLS-DA (stability > 70%) (supplemental Table S10). The combined list of differential proteins was used in order to assess gene ontology differences between sample groups. We used the plasma proteome gene list (45), converted to DAVID IDs as a background in order to test for ontology differences by over-representation analysis using the DAVID (http://david.abcc.ncifcrf.gov/) website (46, 47) with default feature and algorithm settings. Ontology categories with adjusted FDR p values < 0.05 were recorded. Although we report individual ontologies, we applied the built-in functional annotation clustering function to help select representative ontologies for each main cluster (cluster scores over 3).

RESULTS

Esophageal Adenocarcinoma Biomarker Discovery

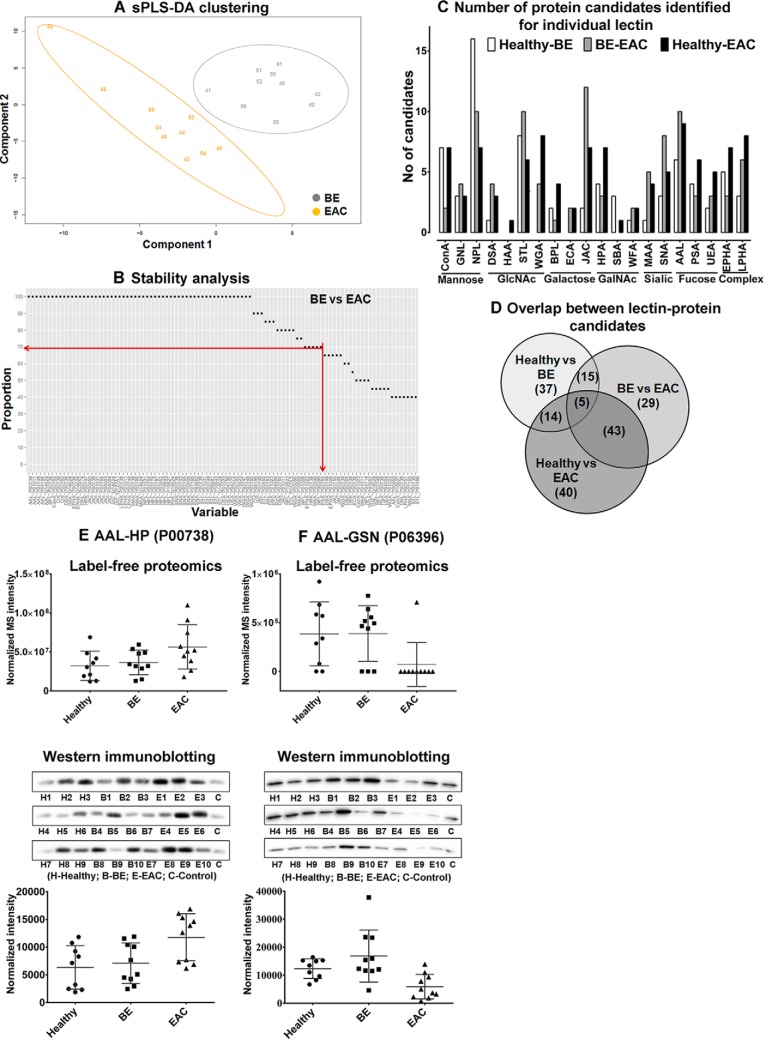

An overview of the integrated glycoprotein biomarker discovery and qualification pipeline is shown in Fig. 1. The discovery phase used age-matched serum samples from 9 healthy, 10 BE, and 10 EAC male patients (Table I). BE and EAC patient groups had a significantly higher proportions of patients with hiatus hernia compared with healthy controls, as has previously been reported (48). We identified a total of 195 unique proteins from the MS/MS data (supplemental Table S2). There was no difference between total number of proteins identified between healthy, BE and EAC patient groups (Supplemental fig. S3). The discovery LeMBA-MS/MS data were uploaded to GlycoSelector for data housing and statistical analysis. The sPLS-DA sample representation, including the top 100 candidates (lectin–protein pairs) in the model, showed clear separation of the samples according to their phenotype (Fig. 2A and supplemental Fig. S4).

Fig. 2.

Biomarker discovery and protein level qualification of two candidates. Serum samples from 29 patients (healthy-9, BE-10 and EAC-10) were screened using the LeMBA-GlycoSelector pipeline. A, The sPLS-DA sample representation based on the top 100 lectin–protein candidates that differentiate EAC from BE. B, Among the top 100 sPLS-DA candidates, 72 candidates passed the stability criteria of 70% based on leave-one-out cross-validation. Results of sPLS-DA and stability analysis for healthy versus BE and healthy versus EAC are available in supplemental Fig. S4. C, Number of unique candidate proteins identified for each lectin in LeMBA-GlycoSelector analysis. All 20 lectins used for screening identified at least one protein candidate. D, Overlap between lectin–protein candidates that differentiate BE from healthy, EAC from BE, and EAC from healthy phenotype. E, AAL-HP and (F) AAL-GSN were the top two candidates identified using sPLS-DA and group binding difference tool, respectively. (E and F, top panel) Label-free proteomics relative quantitation results for AAL-HP and AAL-GSN respectively. (E and F, lower panel) Normalized intensity for AAL-HP and AAL-GSN using immunoblotting. Raw densitometry values are provided in supplemental Table S5.

To select the most consistent candidates across patients to the qualification stage, we used the stability function built into GlycoSelector, which utilizes a leave-one-out strategy to assess the utility of each candidate biomarker. A relatively nonstringent cut-off of 70% was chosen for this purpose. Out of the top 100 lectin–protein pairs, 57 candidates passed the stability cut-off of 70% between healthy versus BE, 72 candidates passed for BE versus EAC, and 76 candidates, passed for healthy versus EAC (Fig. 2B, supplemental Fig. S4, and supplemental Table S4). A second, parallel approach used the group binding difference tool in GlycoSelector, to select on-off candidates that may not be selected by the statistical approach. Using relatively nonstringent criteria of 60%/40% presence/absence, this approach identified another 14, 20, and 26 candidates respectively for healthy versus BE, BE versus EAC, and healthy versus EAC analyses (supplemental Table S4). Candidates identified using sPLS-DA and the group binding differences tools were complementary and showed no overlap between lectin–protein candidates, justifying the use of two different approaches for candidate selection. All 20 lectins used in the discovery phase showed differential binding with anywhere between one (e.g. Helix aspersa agglutinin (HAA)) to 25 (e.g. Narcissus pseudonarcissus lectin (NPL)) glycoprotein candidates for pair-wise comparison between patient phenotypes (Fig. 2C). This suggests widespread changes in the serum glycosylation profile between healthy, BE and EAC samples in agreement with previous studies (31–35). There was considerable overlap between glycoprotein candidates identified between healthy versus BE, BE versus EAC, and healthy versus EAC patient groups (Fig. 2D).

Immunoblotting was used for orthogonal protein level confirmation of the LeMBA-MS/MS screen. We chose two protein candidates that showed altered binding to Aleuria aurantia lectin (AAL) and for which antibodies were commercially available. AAL-haptoglobin (HP; Uniprot entry: P00738) was one of the top ranked candidates in sPLS-DA analysis for healthy versus EAC and BE versus EAC, whereas AAL-gelsolin (GSN; Uniprot entry: P06396) was identified using the group binding difference function of GlycoSelector as on-off change between BE versus EAC and healthy versus EAC. Using the same set of discovery serum samples, we performed pull-down using AAL and measured haptoglobin and gelsolin binding by immunoblotting. A control serum sample was loaded on every blot as a normalizer between membranes. LeMBA-immunoblotting confirmed the MS/MS results (Fig. 2E, 2F, and supplemental Table S5), and showed higher sensitivity as it detected low levels of gelsolin in all patient samples, when some were undetectable by MS/MS (AAL-HP: label-free proteomics p value = 0.0868, western immunoblotting p value = 0.0267; AAL-GSN: label-free proteomics p value = 0.0254, western immunoblotting p value = 0.0019).

Biomarker Qualification

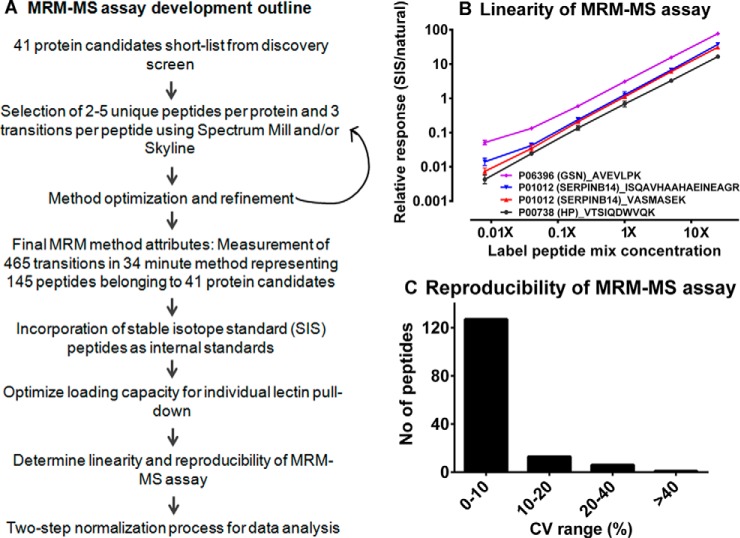

Multiple reaction monitoring-mass spectrometry (MRM-MS) assay was optimized for 41 target protein candidates based on the GlycoSelector results with 2–3 peptides per protein and 2–3 transitions per peptide (Fig. 3A, list of transitions in supplemental Table S6). The linearity of this multiplexed assay was evaluated by spiking four stable isotope standard (SIS) peptides spanning a 3125 fold dilution range (Fig. 3B). The reproducibility of the MRM-MS assay was determined by running the same sample in quadruplicate for four consecutive days. As illustrated in Fig. 3C, 86% of the peptides measured using MRM-MS assay showed % CV below 10%, whereas 9% of peptides showed % CV between 10–20%, and only 5% of the peptides were above 20% suggesting overall reproducibility of MRM-MS assay.

Fig. 3.

Multiple reaction monitoring-mass spectrometry (MRM-MS) assay development outline including determination of assay linearity and reproducibility. A, Outline of MRM-MS assay development. B, Linearity of MRM-MS assay confirmed using SIS labeled peptide mix of four peptides diluted across 3125-fold and spiked-into a constant amount of LeMBA pull-down sample. C, Reproducibility of MRM-MS assay for 16 replicate injections ran over 4 days period.

For the qualification cohort (20 healthy, 20 BE, and 20 EAC; Table II), the prevalence of reflux and obesity was consistent with a previous report (49) showing higher frequency in BE/EAC patient groups compared with the healthy group. Age matched electoral roll control and healthy groups were very similar across all measured covariates (Table II). Based on the GlycoSelector results, we selected 6 lectins (AAL, Erythroagglutinin Phaseolus vulgaris (EPHA), jacalin (JAC), NPL, Pisum sativum agglutinin (PSA), and wheat germ agglutinin (WGA)) for qualification in this independent cohort of samples using MRM-MS assay for 41 target proteins, hence measuring a total of 246 lectin–protein candidates.

Table II. Clinical characteristics of the patient cohort for biomarker qualification. For categorical and numerical variables, p values were calculated using Fisher's exact test and Kruskal-Wallis test respectively.

| Variables | Healthy | BE | EAC | p value (Healthy vs BE vs EAC) | Population Control | p value (Healthy vs Pop. Control) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample size | 20 | 20 | 20 | 19 | ||

| Gender | All male | All male | All male | All male | ||

| Age in years (Median ± S.D.) | 64 ± 8 | 60 ± 8 | 61 ± 7 | 0.4283 | 62 ± 7 | 0.2793 |

| Protein concentration (μg/μl) | 83 ± 10 | 78 ± 12 | 85 ± 13 | 0.6486 | 89 ± 13 | 0.0785 |

| Reflux frequencya (10 years before diagnosis) | 0.0108 | 0.2155 | ||||

| <Once/month | 9 (47.4%) | 7 (35.0%) | 2 (10.0%) | 14 (73.7%) | ||

| Monthly (few times/month) | 6 (31.6%) | 6 (30.0%) | 3 (15.0%) | 4 (21.1%) | ||

| Weekly or daily | 4 (21.0%) | 7 (35.0%) | 15 (75.0%) | 1 (5.3%) | ||

| Body mass index | 0.0076 | 0.6090 | ||||

| Healthy (<25) | 5 (25.0%) | 5 (25.0%) | 1 (5.0%) | 7 (36.8%) | ||

| Overweight (25–30) | 8 (40.0%) | 12 (60.0%) | 5 (25.0%) | 8 (42.1%) | ||

| Obese (> = 30) | 7 (35.0%) | 3 (15.0%) | 14 (70.0%) | 4 (21.1%) | ||

| Smoking history | 0.6116 | 0.7813 | ||||

| Never smoked | 8 (40.0%) | 8 (40.0%) | 4 (20.0%) | 7 (36.8%) | ||

| 1–29.9 pack per year | 8 (40.0%) | 9 (45.0%) | 10 (50.0%) | 6 (31.6%) | ||

| 30+ pack per year | 4 (20.0%) | 3 (15.0%) | 6 (30.0%) | 6 (31.6%) | ||

| Alcohol consumption | 0.6637 | 0.8379 | ||||

| <1 standard drink/week | 3 (15.0%) | 3 (15.0%) | 1 (5.0%) | 2 (10.5%) | ||

| 1–6 standard drink/week | 3 (15.0%) | 4 (20.0%) | 6 (30.0%) | 5 (26.3%) | ||

| 7–20 standard drink/week | 8 (40.0%) | 4 (20.0%) | 6 (30.0%) | 6 (31.6%) | ||

| 21+ standard drink/week | 6 (30.0%) | 9 (45.0%) | 7 (35.0%) | 6 (31.6%) |

a All the analyses were performed based on available patient information. Reflux frequency for one healthy patient was missing.

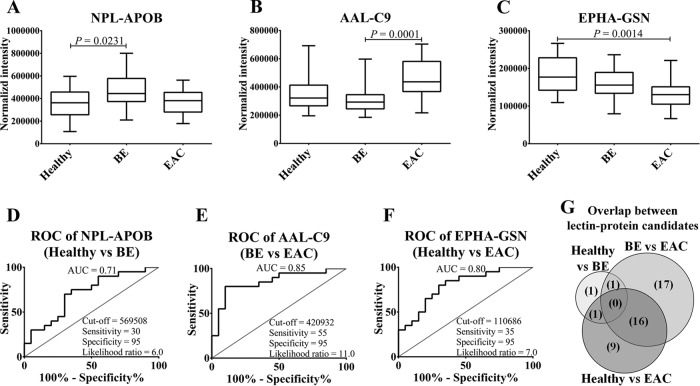

Two sequential steps were used to evaluate and select candidate biomarkers from the qualification data; first, Kruskal-Wallis nonparametric test to assess statistical significance of each individual candidate, then area under receiver operating characteristic (AUROC) curve was used to measure the diagnostic potential of each marker. Pairwise comparisons were made between the three phenotypes: healthy versus BE, BE versus EAC, and healthy versus EAC. Out of 246 lectin–protein candidates, 45 candidates were significantly different between any two groups (FDR < 0.05) (Table III). Among them, 26 lectin–protein candidates showed AUROC of more than 0.7 in at least one of the three phenotype comparisons. Boxplots and ROC curves of the top candidates for healthy versus BE, BE versus EAC, and healthy versus EAC are shown in Fig. 4A to 4F respectively. supplemental Fig. S5 and S6 contain boxplots and ROC curves for all the candidates. As shown in Fig. 4G, 16 candidates overlapped between healthy versus EAC and BE versus EAC analysis and might be of greatest interest as they can differentiate EAC from healthy as well as BE phenotype.

Table III. Verified list of candidates shown by lectin affinity-protein ID that were significantly different for either healthy versus BE or BE versus EAC or healthy versus EAC analysis. Proteins are denoted using gene symbol; number in the bracket denotes Uniprot accession number. AUROC values of more than 0.7 are highlighted in bold.

| Lectin-Protein | Healthy vs BE |

BE vs EAC |

Healthy vs EAC |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| p value | AUROC | p value | AUROC | p value | AUROC | |

| AAL-APOB (P04114) | 0.1368 | 0.6375 | 0.0453 | 0.6850 | 0.9569 | 0.4950 |

| AAL-C5 (P01031) | 0.6073 | 0.5475 | 0.0483 | 0.6825 | 0.2340 | 0.6100 |

| AAL-C7 (P10643) | 0.2793 | 0.6000 | 0.0063 | 0.7525 | 0.3169 | 0.5925 |

| AAL-C9 (P02748) | 0.2793 | 0.6000 | 0.0001 | 0.8525 | 0.0161 | 0.7225 |

| AAL-GSN (P06396) | 0.7455 | 0.5300 | 0.0087 | 0.7425 | 0.0265 | 0.7050 |

| AAL-HP (P00738) | 0.8711 | 0.4850 | 0.0398 | 0.6900 | 0.0583 | 0.6750 |

| EPHA-A2 M (P01023) | 0.0248 | 0.7075 | 0.9138 | 0.4900 | 0.0186 | 0.7175 |

| EPHA-AHSG (P02765) | 0.5162 | 0.5600 | 0.1941 | 0.6200 | 0.0483 | 0.6825 |

| EPHA-C7 (P10643) | 0.1368 | 0.6375 | 0.0398 | 0.6900 | 0.6849 | 0.5375 |

| EPHA-C9 (P02748) | 0.0583 | 0.6750 | 0.0003 | 0.8375 | 0.0265 | 0.7050 |

| EPHA-GSN (P06396) | 0.2036 | 0.6175 | 0.0200 | 0.7150 | 0.0014 | 0.7950 |

| EPHA-HP (P00738) | 0.7455 | 0.5300 | 0.0200 | 0.7150 | 0.0305 | 0.7000 |

| EPHA-SERPINA3 (P01011) | 0.4171 | 0.5750 | 0.0265 | 0.7050 | 0.0620 | 0.6725 |

| EPHA-TF (P02787) | 0.7455 | 0.4700 | 0.0326 | 0.6975 | 0.0935 | 0.6550 |

| JAC-A1BG (P04217) | 0.6263 | 0.5450 | 0.0483 | 0.6825 | 0.1231 | 0.6425 |

| JAC-APOB (P04114) | 0.0305 | 0.7000 | 0.0699 | 0.6675 | 0.5700 | 0.5525 |

| JAC-C4BPA (P04003) | 0.7251 | 0.5325 | 0.0935 | 0.6550 | 0.0128 | 0.7300 |

| JAC-C5 (P01031) | 0.6073 | 0.4525 | 0.0425 | 0.6875 | 0.0483 | 0.6825 |

| JAC-C7 (P10643) | 0.2914 | 0.5975 | 0.0094 | 0.7400 | 0.0834 | 0.6600 |

| JAC-C9 (P02748) | 0.2914 | 0.5975 | 0.0007 | 0.8125 | 0.0029 | 0.7750 |

| JAC-CFB (P00751) | 0.9353 | 0.5075 | 0.0373 | 0.6925 | 0.0373 | 0.6925 |

| JAC-GSN (P06396) | 0.8498 | 0.5175 | 0.0305 | 0.7000 | 0.0215 | 0.7125 |

| JAC-HP (P00738) | 0.9569 | 0.5050 | 0.0483 | 0.6825 | 0.0583 | 0.6750 |

| JAC-HPX (P02790) | 0.7868 | 0.5250 | 0.0742 | 0.6650 | 0.0200 | 0.7150 |

| JAC-SERPINA1 (P01009) | 0.3040 | 0.5950 | 0.0453 | 0.6850 | 0.2448 | 0.6075 |

| JAC-SERPINA3 (P01011) | 0.9569 | 0.5050 | 0.0102 | 0.7375 | 0.0305 | 0.7000 |

| JAC-SERPIND1 (P05546) | 0.1368 | 0.6375 | 0.4819 | 0.5650 | 0.0483 | 0.6825 |

| JAC-SERPING1 (P05155) | 0.5518 | 0.5550 | 0.2559 | 0.6050 | 0.0200 | 0.7150 |

| NPL-AFM (P43652) | 0.5338 | 0.5575 | 0.0483 | 0.6825 | 0.1762 | 0.6250 |

| NPL-APOB (P04114) | 0.0231 | 0.7100 | 0.0231 | 0.7100 | 0.8924 | 0.5125 |

| NPL-C4BPA (P04003) | 0.0989 | 0.6525 | 0.6849 | 0.5375 | 0.0231 | 0.7100 |

| NPL-C9 (P02748) | 0.5885 | 0.5500 | 0.0049 | 0.7600 | 0.0074 | 0.7475 |

| NPL-GSN (P06396) | 0.8924 | 0.5125 | 0.0173 | 0.7200 | 0.0583 | 0.6750 |

| NPL-HP (P00738) | 0.8077 | 0.5225 | 0.0884 | 0.6575 | 0.0326 | 0.6975 |

| NPL-SERPINA3 (P01011) | 0.5518 | 0.5550 | 0.0989 | 0.6525 | 0.0305 | 0.7000 |

| PSA-C5 (P01031) | 0.4017 | 0.5775 | 0.0453 | 0.6850 | 0.3040 | 0.5950 |

| PSA-C7 (P10643) | 0.2914 | 0.5975 | 0.0019 | 0.7875 | 0.0742 | 0.6650 |

| PSA-C9 (P02748) | 0.2036 | 0.6175 | 0.0008 | 0.8100 | 0.0161 | 0.7225 |

| PSA-GSN (P06396) | 0.3577 | 0.5850 | 0.0483 | 0.6825 | 0.0110 | 0.7350 |

| PSA-HP (P00738) | 0.8498 | 0.4825 | 0.0483 | 0.6825 | 0.0425 | 0.6875 |

| PSA-SERPINA3 (P01011) | 0.8077 | 0.5225 | 0.0425 | 0.6875 | 0.0834 | 0.6600 |

| WGA-C9 (P02748) | 0.4819 | 0.5650 | 0.0032 | 0.7725 | 0.0053 | 0.7575 |

| WGA-GSN (P06396) | 0.7868 | 0.5250 | 0.0119 | 0.7325 | 0.0742 | 0.6650 |

| WGA-HP (P00738) | 0.7455 | 0.5300 | 0.0483 | 0.6825 | 0.0215 | 0.7125 |

| WGA-SERPINA3 (P01011) | 0.4819 | 0.5650 | 0.0989 | 0.6525 | 0.0063 | 0.7525 |

Fig. 4.

Qualification of lectin–protein biomarker candidates in an independent patient cohort. A to F, Boxplots and ROC curves of top biomarker candidate for healthy versus BE, BE versus EAC, and healthy versus EAC comparison, respectively. G, Overlap between lectin–protein candidates that differentiate BE from healthy, EAC from BE, and EAC from healthy phenotype. p values were calculated using Kruskal-Wallis test and p < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Orthogonal qualification at protein level using LeMBA-immunoblotting (IB) was performed for AAL-HP and AAL-GSN using samples from the qualification cohort. Once again, there was agreement between peptide level quantitation using MRM-MS and protein level quantitation using IB (supplemental Fig. S7 and supplemental Table S9), validating the LeMBA-MRM-MS workflow (AAL-HP: MRM-MS p value = 0.0235, western immunoblotting p value = 0.1037, MRM-MS AUROC = 0.69, western immunoblotting AUROC = 0.69;AAL-GSN: MRM-MS p value = 0.0120, western immunoblotting p value = 0.0203, MRM-MS AUROC = 0.70, western immunoblotting AUROC = 0.73). For further evaluation, we undertook functional enrichment analysis of the list of candidates that differentiated EAC from BE, which included 17 unique proteins from 59 lectin–protein pairs (supplemental Table S10). In agreement with the glycoprotein enrichment strategy, the top Annotation Cluster with an Enrichment Score of 10.4 included SP_PIR_KEYWORD glycoprotein (p = 1.82E-08) and the UP_SEQ_FEATURE glycosylation site:N-linked (GlcNAc …) (p = 2.32E-06). Additional clusters related to acute inflammation, complement cascade pathway, and endopeptidase inhibition, were over-represented within the 17 genes that discriminated BE and EAC. KEGG “Complement and coagulation cascades” pathway (hsa04610) was significantly over-represented (p = 4.6E-18), including ten genes compared with the full list of plasma proteins. This result is in agreement with the involvement of inflammation in BE to EAC pathogenesis (50, 51), and points to alterations in the complement cascade in EAC development.

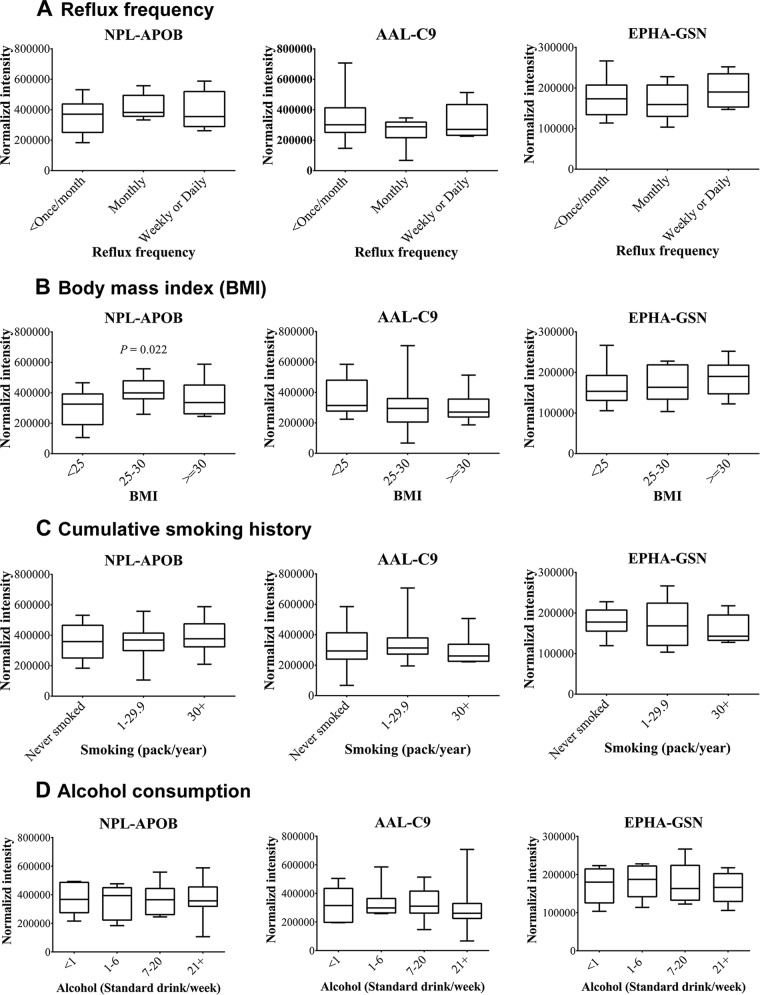

Identification of Candidates Affected by Confounding Covariates

As expected from the known risk factors, healthy, BE and EAC patient groups significantly differ according to BMI and reflux frequency (Table II). Compared with healthy patients, BE and EAC patient groups had a higher proportion of patients who were obese or experienced frequent GERD. Moreover, functional annotation analysis suggest enrichment of the pathways related to inflammation between BE and EAC. Therefore, it may be possible that some of the candidates identified are because of confounding covariates rather than the actual disease phenotype. To evaluate this hypothesis, first the cohort size of healthy phenotype was increased by LeMBA-MRM-MS measurement of an additional 19 control serum samples collected as disease-free, electoral roll samples. These 39 disease-free patient samples were then classified according to potential confounding variables (reflux frequency, BMI, cumulative smoking history and alcohol consumption). The statistical significance of each 45 lectin–protein candidates for each of the four covariates was assessed using a Kruskal-Wallis test. Most of the candidate biomarkers were not significantly correlated with the covariates. As examples, boxplots of the data for the top 3 biomarker candidates of the disease-free cohort classified according to covariates are shown in Fig. 5. Out of the four covariates studied, reflux frequency is perhaps the most important factor to be considered in the context of BE/EAC. Notably, none of the candidates were affected by reflux frequency, suggesting specificity of the candidates to diagnose disease phenotype. Five candidates significantly correlated with covariates (supplemental Table S11 and supplemental Fig. S8). Apolipoprotein B-100 (APOB; Uniprot entry: P04114) showed differential binding with lectins AAL, JAC, and NPL according to BMI classification. This is most likely because of increased levels of total APOB with increase in BMI, suggesting underlying changes in the lipoprotein metabolism (52). Plasma protease C1 inhibitor (SERPING1; Uniprot entry: P05155) showed significantly reduced binding with JAC lectin in samples classified as overweight and obese as compared with healthy whereas JAC-alpha-1B-glycpoprotein (A1BG; Uniprot entry: P04217) varied according to alcohol consumption. This covariate analysis led us to eliminate 5 candidates from the qualified biomarker list, leaving 40 biomarker candidates for future studies. Out of the five candidates that were eliminated, JAC-APOB was identified in healthy versus BE analysis, AAL-APOB and JAC-A1BG were identified in BE versus EAC analysis, JAC-SERPING1 was identified in healthy versus EAC analysis whereas NPL-APOB was significantly different in healthy versus BE and BE versus EAC analysis. Notably, none of the 16 lectin–protein candidates that distinguish EAC from BE and healthy phenotype were identified as confounding candidates.

Fig. 5.

Assessing effect of confounding covariates on the top 3 biomarker candidates. Levels of NPL-APOB, AAL-C9 and EPHA-GSN were monitored in 39 serum samples (healthy-20 and population control-19) using MRM-MS. Samples were categorized according to (A) reflux frequency, (B) BMI, (C) smoking history and (D) alcohol consumption. p < 0.05 using Kruskal-Wallis test was considered to be statistically significant. Out of the top 3 candidates, only NPL-APOB was significantly different according BMI categorization.

Multimarker Panel for EAC

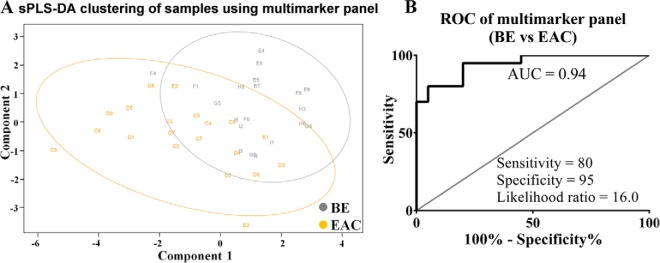

Next we examined the potential of protein glycoforms as complementary biomarkers, focusing on differential diagnosis of EAC and BE, because this is critical for making clinical decisions. After removal of confounding candidates, sPLS-DA was used to derive a multimarker panel that distinguish BE and EAC (Fig. 6A). The biomarker panel (BE versus EAC) included four unique proteins namely complement component C9 (C9; Uniprot entry: P02748), α-1B-glycoprotein (A1BG; Uniprot entry: P04217), complement C4-B (C4B; Uniprot entry: P0C0L5) and complement C2 (C2; Uniprot entry: P06681) with each of the six lectins appearing at least once in the panel. Using fivefold cross-validation repeated 1000 times on this multimarker panel, the model showed cross-validation error rate of 37.47% and moderate separation of the BE and EAC sample representations (Fig. 6A). The combined signature of the eight candidates gave an AUROC of 0.9425 with 95% specificity and 80% sensitivity (Fig. 6B).

Fig. 6.

Multimarker panel to distinguish EAC from BE. A, sPLS-DA and (B) ROC curve analysis of a multimarker panel consists of AAL-C9, EPHA-A1BG, EPHA-C9, JAC-C9, NPL-C2, NPL-C4B, PSA-C9, and WGA-C9.

DISCUSSION

In this study we present an alternative workflow to identify glycosylation changes in medium to high abundant glycoproteins using serum as the sample source and lectins to interrogate glycan moieties throughout discovery and qualification. Our workflow was designed to enhance the feasibility of glycoprotein biomarker discovery and translation, through scientific rigor while managing the experimental cost. First, serum was used as the sample source throughout discovery and qualification, hence eliminating the risk of switching tissue type during biomarker development. Second, single step enrichment using liquid handler assisted LeMBA-system reduced sample processing variability. Third, we utilized the comparatively inexpensive approach of label-free proteomics using relative quantitation with respect to a spiked-in internal standard chicken ovalbumin. This approach achieved the necessary analytical linearity and reproducibility throughout the more than 2000 h of total mass spectrometer run time performed in the study. This cost-effective strategy can be applied across other existing proteomics platforms to account for variations during sample processing and enable relative quantitation for a large number of candidates without costly SIS labeled peptides. Fourth, we applied a sequential filtering approach (53) in which many candidates were selected from biomarker discovery proteomics data, and qualified using MRM-MS with increasing sample size in a cost-effective manner. Finally, we introduced software tools for data visualization and statistical analysis in the form of web-interfaces. Both GlycoSelector (http://glycoselector.di.uq.edu.au) and Shiny mixOmics (http://mixomics-projects.di.uq.edu.au/Shiny) platforms are publicly available, user-friendly and require minimal and no background in statistics or computer programming.

The main feature of both these web-interfaces is the use of multivariate sPLS-DA method which enables data dimension reduction, insightful graphical outputs and the identification of key discriminative features with respect to the biological outcome of interest. In Shiny mixOmics we have added important preliminary data mining steps for 'omics' data visualization such as sample boxplots, coefficient of variation barplots, hierarchical clustering, PCA in order to identify potential outliers prior to statistical analyses. The univariate statistical analysis step includes Krukal-Wallis, ANOVA tests as well as ROC analysis that can be performed efficiently on thousands of variables and results can also be output in a common file format. Although similar sorts of analyses can be performed using commercially available software packages such as GraphPad Prism or Origin, these require additional computer programming skills in order to automate the analysis for hundreds of data points. Finally, the multivariate statistical analysis step with sPLS-DA (also separately available in the R package mixOmics) (39) has been shown to identify relevant biological features, with a classification performance similar to other statistical approaches (40). The major advantage of such an approach is graphical representation of the results that univariate approaches cannot provide. Importantly, in this study we have shown that such multivariate methods can be used efficiently and reliably on proteomics data characterized by highly skewed and non normal distributions. Collectively, the two web-interface statistical tools that we propose enable data mining, univariate and multivariate statistical analyses that can be applied to other “omics” data sets.

The success of cancer screening programs in improving outcomes for many cancer types emphasizes the importance of early diagnosis and the development of screening/surveillance tools (54). The lack of cost-effective screening/surveillance methodology to facilitate early diagnosis of EAC is one of the main reasons for the high mortality. Current endoscopy-based screening is costly, requires specialist appointment, and is not suitable for frequent large scale at risk population monitoring (27, 30). Several innovative screening methods are being evaluated, including advanced imaging (55, 56), nonendoscopic sampling (57, 58), and blood biomarkers (30). Recently conducted genome profiling studies using next-generation sequencing platforms have concluded that the majority of key mutations are already acquired at the metaplastic stage of BE and only few driver mutations lead to progression of dysplasia and EAC (59, 60). This suggests that genomics-based screening approaches may have limitations as a screening technology. Despite this, the evidence for limited genomic changes between BE and EAC raises the possibility that more functional level changes (e.g. protein expression, protein glycosylation, metabolic changes etc.) may be driving the development of dysplasia/carcinoma from metaplastic condition. In line with this, studies have shown differential expression of glycan structures in tissue and serum samples during metaplasia-dysplasia-carcinoma sequence (23, 31–35, 61–65).

Out of the 246 lectin–protein candidates measured for qualification, 45 candidates (18.3%) were qualified in an independent cohort of patients. Interestingly, only three out of 45 candidates were significantly different between healthy versus BE comparison, with the other 42 candidates differentially present in EAC as compared with either healthy or BE samples. This suggests that EAC phenotype is significantly different from BE and healthy in terms of serum glycan expression. The lack of glycosylation changes between healthy and BE was somewhat surprising because genomic studies suggest that BE and EAC share a common mutational profile that differs from healthy samples (59, 60). The top candidate that differentiated between healthy and BE, NPL-APOB, was influenced by BMI. Hence, except EPHA-Alpha-2-macroglobulin (A2M), this study did not find any candidate that can differentiate BE from healthy, suggesting little or no change in glycosylation of serum proteins in the development of BE. However, the critical diagnostic need is to identify patients at early dysplasia or early stages of EAC, or those at high risk of progression. To progress toward this goal, the lectin–protein biomarker candidates should be evaluated in a patient cohort including low grade dysplasia (LGD) and high grade dysplasia (HGD) phenotypes to precisely determine what disease stage can actually be diagnosed by the glycoprotein biomarker candidates.

Previous serum glycan profiling studies found reductions in total N-linked fucosylation in EAC as compared with healthy patient groups (33, 35). Here we used two fucose specific lectins AAL and PSA, both of them showed differential binding with 6 glycoproteins for BE versus EAC pair-wise comparison. Out of six glycoproteins that showed differential binding to fucose specific lectins, four showed increased levels in EAC samples for AAL lectin pull-down, whereas five candidates showed increased levels in EAC samples as compared with BE for PSA lectin pull-down. These data suggest that serum glycan changes are specific to the glycoprotein of origin, and this property could be exploited as a specific biomarker compared with overall changes in serum fucosylation.

Apart from the major goal of translating the biomarkers for diagnosis, the verified biomarkers could shed light on the pathogenesis of EAC. To this end, functional annotation analysis of the candidates was able to distinguish between EAC and BE through enrichment of “complement and coagulation cascades” pathway. Very recently Song and colleagues (23) also identified changes in the glycosylation of complement proteins for EAC and high grade dysplasia compared with a healthy phenotype. They used lectin-affinity chromatography (a mix of fucose and sialic acid binding lectin) and hydrazide chemistry-based glycoprotein enrichment methods to identify complement C3 and complement C1r subcomponent as differentially present in HGD and EAC samples respectively, as compared with serum from healthy cohort. The differences between these complement proteins, and those that discriminate BE and EAC, in our results, may be the result of divergent sample processing steps. For example, Song et al. (23) used serum sample after depletion of the seven most abundant proteins as compared with our workflow where as we denatured the serum samples to break protein complexes without depletion of abundant proteins. In our workflow we used an individual lectin for enrichment of a particular type of glycan whereas Song and colleagues used a mixture of sialic acid binding Sambucus nigra agglutinin (SNA) and fucose specific AAL lectin for glycoprotein enrichment. Nonetheless, changes observed in the glycosylation of complement proteins may suggest a role for inflammation in EAC pathogenesis (50).

Although lectins are a useful tool for discovery and translation, a limitation of our pipeline is the lack of identification of the actual glycosylation sites and glycan structures. For rapid translation of the verified biomarkers using a simple lectin-immunoassay format that can be readily achieved, the only information required is the lectin affinity and the protein identity. Hence, we have not incorporated detailed glycosylation site or glycan structure analysis to the current pipeline. Following further clinical evaluation, the final glycoprotein candidates could be subjected to full glycomics characterization to determine the changes in the glycan structure and/or site of glycosylation between different disease states. This may provide additional insight into the pathological basis of the cancer-associated glycosylation changes. We anticipate 3 possible scenarios for a glycoprotein to show differential lectin binding in our LeMBA based workflow. (1) Total glycoprotein level changes would lead to overall increased/decreased binding with multiple lectins. (2) Changes in the glycan occupancy at a particular glycosylation site will lead to differential binding with multiple lectins. (3) Differential expression of a specific glycan structure will alter binding of a glycoprotein to a particular lectin or a group of lectins. Further studies following biomarker qualification will be required to identify the exact mechanism of differential lectin binding for each candidate.

In summary, we have developed novel tools for glycoprotein biomarker discovery using serum. The cross-sectional pre-clinical biomarker exploratory study conducted using our workflow has identified a list of serum glycoprotein candidate biomarkers that can distinguish EAC from healthy and BE phenotype. These candidates will need to be further evaluated in independent cohorts of patient samples that include different disease grades and subtypes, prior to prospective trials. The pipeline developed can be applied to other diseases with software tools GlycoSelector and Shiny mixOmics available online at http://glycoselector.di.uq.edu.au/ and http://mixomics-projects.di.uq.edu.au/Shiny.

The raw mass spectrometry data along with database search results including sequence database used for searches have been deposited to the publicly accessible platform ProteomeXchange Consortium (66) via the PRIDE partner repository with the data set identifier PXD002442. The peptide identification results can be viewed using MS-Viewer (http://prospector2.ucsf.edu/prospector/cgi-bin/msform.cgi?form=msviewer) (67), using search key jn7qafftux.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dorothy Loo (The University of Queensland Diamantina Institute, The University of Queensland) and Dr Thomas Hennessey (Agilent Technologies) for technical assistance during mass spectrometric analysis. We would like to thank Peter Baker and Robert Chalkley of University of California, San Francisco and Karl Clauser of Broad Institute of Harvard and MIT for their generous and extended support to enable MS-Viewer to visualize our proteomics data set.

Footnotes

Author contributions: A.K.S., E.C., and M.M.H. designed research; A.K.S. and E.C. performed research; A.K.S., K.L., E.C., D.C., and B.G. contributed new reagents or analytic tools; A.K.S., K.L., E.C., B.G., D.N., and M.M.H. analyzed data; A.K.S., K.L., E.C., D.C.W., N.A.S., V.J., and M.M.H. wrote and edited the paper; D.N. and D.C.W. collected patient samples and performed sample selection; N.A.S. and A.P.B. supervised parts of the project; M.M.H. conceived and supervised the project.

* This project was supported in part by grants from the University of Queensland-Ochsner Seed Fund for Collaborative Research (to M.M.H., A.P.B. and V.J.). Specialized instrumentation for the project was partly supported by the Ramaciotti Foundations and the Australian Cancer Research Foundation (ACRF). Serum samples for the study were acquired through The Australian Cancer Study (ACS), which was funded by Program Grants from the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) of Australia (199600, 552429), and Study of Digestive Health (SDH), which was supported by grant number 5 RO1 CA 001833–02 from the National Cancer Institute. M.M.H. was supported by the NHMRC of Australia Career Development Fellowship (569512). K.A.L.C. is supported in part by the Diamantina Individualized Oncology Care Centre (ACRF). D.C.W is supported by a Research Fellowship (APP1058522) from the NHMRC of Australia. N.A.S. is supported by a Senior Research Fellowship awarded by the Cancer Council Queensland, and grants from the Australian NHMRC (APP1049182) and the Cancer Council Queensland (APP1025479). A.K.S. is a recipient of International Postgraduate Research Scholarship and The University of Queensland Centennial Scholarship. E. C. was supported by The University of Queensland International Research Tuition Award and The University of Queensland Research Scholarship.

This article contains supplemental Methods, Figs. S1 to S8, and Tables S1 to S11.

This article contains supplemental Methods, Figs. S1 to S8, and Tables S1 to S11.

1 The abbreviations used are:

- LeMBA

- Lectin magnetic bead array

- A1BG

- Alpha-1B-glycoprotein

- A2M

- Alpha-2-macroglobulin

- AAL

- Aleuria aurantia lectin

- APOB

- Apolipoprotein B-100

- AUROC

- Area under receiver operating characteristic curve

- BE

- Barrett's esophagus

- BMI

- Body mass index

- BPL

- Bauhinia purpurea lectin

- C2

- Complement C2

- C4B

- Complement C4-B

- C9

- Complement component C9

- ConA

- Concanavalin A from Canavalia ensiformis

- CV

- Co-efficient of variation

- DSA

- Datura stramonium agglutinin

- EAC

- Esophageal adenocarcinoma

- ECA

- Erythrina cristagalli agglutinin

- EPHA

- Erythroagglutinin Phaseolus vulgaris

- GalNAc

- N-acetylgalactosamine

- GERD

- Gastroesophageal reflux disease

- GlcNAc

- N-acetylglucosamine

- GNL

- Galanthus nivalis lectin

- GSN

- Gelsolinl

- HAA

- Helix aspersa agglutinin

- HGD

- High grade dysplasia

- HP

- Haptoglobin

- HPA

- Helix pomatia agglutinin

- JAC

- Jacalin from Artocarpus integrifolia

- LPHA

- Leukoagglutinating phytohemagglutinin

- MAA

- Maackia amurensis agglutinin

- NPL

- Narcissus pseudonarcissus lectin

- PSA

- Pisum sativum agglutinin

- SBA

- Soybean agglutinin

- SERPING1

- Plasma protease C1 inhibitor

- SIS

- Stable isotope standard

- SNA

- Sambucus nigra agglutinin

- sPLS-DA

- Sparse partial least squares-discriminant analysis

- STL

- Solanum tuberosum lectin

- UEA

- Ulex europeus agglutinin-I

- WFA

- Wisteria floribunda agglutinin

- WGA

- Wheat germ agglutinin.

REFERENCES

- 1. Anderson N. L., Ptolemy A. S., and Rifai N. (2013) The riddle of protein diagnostics: future bleak or bright? Clin. Chem. 59, 194–197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Pavlou M. P., Diamandis E. P., and Blasutig I. M. (2013) The long journey of cancer biomarkers from the bench to the clinic. Clin. Chem. 59, 147–157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Rifai N., Gillette M. A., and Carr S. A. (2006) Protein biomarker discovery and validation: the long and uncertain path to clinical utility. Nat. Biotechnol. 24, 971–983 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Diamandis E. P. (2010) Cancer biomarkers: can we turn recent failures into success? J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 102, 1462–1467 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Addona T. A., Shi X., Keshishian H., Mani D. R., Burgess M., Gillette M. A., Clauser K. R., Shen D., Lewis G. D., Farrell L. A., Fifer M. A., Sabatine M. S., Gerszten R. E., and Carr S. A. (2011) A pipeline that integrates the discovery and verification of plasma protein biomarkers reveals candidate markers for cardiovascular disease. Nat. Biotechnol. 29, 635–643 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Keshishian H., Burgess M. W., Gillette M. A., Mertins P., Clauser K. R., Mani D. R., Kuhn E. W., Farrell L. A., Gerszten R. E., and Carr S. A. (2015) Multiplexed, Quantitative Workflow for Sensitive Biomarker Discovery in Plasma Yields Novel Candidates for Early Myocardial Injury. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 14, 2375–2393 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ademowo O. S., Hernandez B., Collins E., Rooney C., Fearon U., van Kuijk A. W., Tak P. P., Gerlag D. M., FitzGerald O., and Pennington S. R. (2014) Discovery and confirmation of a protein biomarker panel with potential to predict response to biological therapy in psoriatic arthritis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. DOI 10.1136/annrheumdis-2014-205417 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Whiteaker J. R., Zhang H., Zhao L., Wang P., Kelly-Spratt K. S., Ivey R. G., Piening B. D., Feng L. C., Kasarda E., Gurley K. E., Eng J. K., Chodosh L. A., Kemp C. J., McIntosh M. W., and Paulovich A. G. (2007) Integrated pipeline for mass spectrometry-based discovery and confirmation of biomarkers demonstrated in a mouse model of breast cancer. J. Proteome Res. 6, 3962–3975 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Liu N. Q., Braakman R. B., Stingl C., Luider T. M., Martens J. W., Foekens J. A., and Umar A. (2012) Proteomics pipeline for biomarker discovery of laser capture microdissected breast cancer tissue. J. Mammary Gland Biol. Neoplasia 17, 155–164 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Whiteaker J. R., Lin C., Kennedy J., Hou L., Trute M., Sokal I., Yan P., Schoenherr R. M., Zhao L., Voytovich U. J., Kelly-Spratt K. S., Krasnoselsky A., Gafken P. R., Hogan J. M., Jones L. A., Wang P., Amon L., Chodosh L. A., Nelson P. S., McIntosh M. W., Kemp C. J., and Paulovich A. G. (2011) A targeted proteomics-based pipeline for verification of biomarkers in plasma. Nat. Biotechnol. 29, 625–634 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Paulovich A. G., Whiteaker J. R., Hoofnagle A. N., and Wang P. (2008) The interface between biomarker discovery and clinical validation: The tar pit of the protein biomarker pipeline. Proteomics Clin. Appl. 2, 1386–1402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Choi E., Loo D., Dennis J. W., O'Leary C. A., and Hill M. M. (2011) High-throughput lectin magnetic bead array-coupled tandem mass spectrometry for glycoprotein biomarker discovery. Electrophoresis 32, 3564–3575 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Loo D., Jones A., and Hill M. M. (2010) Lectin magnetic bead array for biomarker discovery. J. Proteome Res. 9, 5496–5500 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Fanayan S., Hincapie M., and Hancock W. S. (2012) Using lectins to harvest the plasma/serum glycoproteome. Electrophoresis 33, 1746–1754 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Drake R. R., Schwegler E. E., Malik G., Diaz J., Block T., Mehta A., and Semmes O. J. (2006) Lectin capture strategies combined with mass spectrometry for the discovery of serum glycoprotein biomarkers. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 5, 1957–1967 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kim E. H., and Misek D. E. Glycoproteomics-based identification of cancer biomarkers. Int. J. Proteomics 2011:601937, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kuzmanov U., Kosanam H., and Diamandis E. P. (2013) The sweet and sour of serological glycoprotein tumor biomarker quantification. BMC Med. 11, 31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Cummings R. D., and Kornfeld S. (1982) Fractionation of asparagine-linked oligosaccharides by serial lectin-Agarose affinity chromatography. A rapid, sensitive, and specific technique. J. Biol. Chem. 257, 11235–11240 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Yang Z., and Hancock W. S. (2004) Approach to the comprehensive analysis of glycoproteins isolated from human serum using a multi-lectin affinity column. J. Chromatogr. A 1053, 79–88 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Drake P. M., Schilling B., Niles R. K., Braten M., Johansen E., Liu H., Lerch M., Sorensen D. J., Li B., Allen S., Hall S. C., Witkowska H. E., Regnier F. E., Gibson B. W., and Fisher S. J. (2011) A lectin affinity workflow targeting glycosite-specific, cancer-related carbohydrate structures in trypsin-digested human plasma. Anal. Biochem. 408, 71–85 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Li Y., Shah P., De Marzo A. M., Van Eyk J. E., Li Q., Chan D. W., and Zhang H. (2015) Identification of glycoproteins containing specific glycans using a lectin-chemical method. Anal. Chem. 87, 4683–4687 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Zhou H., Froehlich J. W., Briscoe A. C., and Lee R. S. (2013) The GlycoFilter: a simple and comprehensive sample preparation platform for proteomics, N-glycomics and glycosylation site assignment. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 12, 2981–2991 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Song E., Zhu R., Hammoud Z. T., and Mechref Y. (2014) LC-MS/MS quantitation of esophagus disease blood serum glycoproteins by enrichment with hydrazide chemistry and lectin affinity chromatography. J. Proteome Res. 13, 4808–4820 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kagebayashi C., Yamaguchi I., Akinaga A., Kitano H., Yokoyama K., Satomura M., Kurosawa T., Watanabe M., Kawabata T., Chang W., Li C., Bousse L., Wada H. G., and Satomura S. (2009) Automated immunoassay system for AFP-L3% using on-chip electrokinetic reaction and separation by affinity electrophoresis. Anal. Biochem. 388, 306–311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Sato Y., Nakata K., Kato Y., Shima M., Ishii N., Koji T., Taketa K., Endo Y., and Nagataki S. (1993) Early recognition of hepatocellular carcinoma based on altered profiles of alpha-fetoprotein. N. Engl. J. Med. 328, 1802–1806 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hur C., Miller M., Kong C. Y., Dowling E. C., Nattinger K. J., Dunn M., and Feuer E. J. (2013) Trends in esophageal adenocarcinoma incidence and mortality. Cancer 119, 1149–1158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Spechler S. J., and Souza R. F. (2014) Barrett's esophagus. N. Engl. J. Med. 371, 836–845 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Reid B. J., Li X., Galipeau P. C., and Vaughan T. L. (2010) Barrett's oesophagus and oesophageal adenocarcinoma: time for a new synthesis. Nat. Rev. Cancer 10, 87–101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Rutegard M., Lagergren P., Nordenstedt H., and Lagergren J. (2011) Oesophageal adenocarcinoma: the new epidemic in men? Maturitas 69, 244–248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Shah A. K., Saunders N. A., Barbour A. P., and Hill M. M. (2013) Early diagnostic biomarkers for esophageal adenocarcinoma–the current state of play. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 22, 1185–1209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Gaye M. M., Valentine S. J., Hu Y., Mirjankar N., Hammoud Z. T., Mechref Y., Lavine B. K., and Clemmer D. E. (2012) Ion mobility-mass spectrometry analysis of serum N-linked glycans from esophageal adenocarcinoma phenotypes. J. Proteome Res. 11, 6102–6110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hu Y., Desantos-Garcia J. L., and Mechref Y. (2013) Comparative glycomic profiling of isotopically permethylated N-glycans by liquid chromatography/electrospray ionization mass spectrometry. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 27, 865–877 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Mechref Y., Hussein A., Bekesova S., Pungpapong V., Zhang M., Dobrolecki L. E., Hickey R. J., Hammoud Z. T., and Novotny M. V. (2009) Quantitative serum glycomics of esophageal adenocarcinoma and other esophageal disease onsets. J. Proteome Res. 8, 2656–2666 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Mitra I., Zhuang Z., Zhang Y., Yu C. Y., Hammoud Z. T., Tang H., Mechref Y., and Jacobson S. C. (2012) N-glycan profiling by microchip electrophoresis to differentiate disease states related to esophageal adenocarcinoma. Anal. Chem. 84, 3621–3627 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Hammoud Z. T., Mechref Y., Hussein A., Bekesova S., Zhang M., Kesler K. A., and Novotny M. V. (2010) Comparative glycomic profiling in esophageal adenocarcinoma. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 139, 1216–1223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]