Abstract

The small quantities of protein required for mass spectrometry (MS) make it a powerful tool to detect binding (protein–protein, protein–small molecule, etc.) of proteins that are difficult to express in large quantities, as is the case for many intrinsically disordered proteins. Chemical cross-linking, proteolysis, and MS analysis, combined, are a powerful tool for the identification of binding domains. Here, we present a traditional approach to determine protein–protein interaction binding sites using heavy water (18O) as a label. This technique is relatively inexpensive and can be performed on any mass spectrometer without specialized software.

Keywords: Mass spectrometry, Cross-linking, In-gel digest, Heavy (18O) water

1. Introduction

Intrinsically disordered regions and proteins by their disordered nature make it inherently difficult to crystallize and thus determine their three dimensional structures as well as identifying intermolecular interactions (1). Mass spectrometry (MS) is a powerful tool that has become indispensible for proteomic studies, affording the identification of thousands of proteins in a single experiment (2). In recent years, new mass spectrometry techniques have been developed to move beyond protein identification and analyze the binding domains formed during protein–protein interactions. One such approach has been to use chemical cross-linking in conjunction with proteolysis and mass spectrometric analysis (3–9). This approach takes advantage of several characteristics of MS measurements (10): (1) Cross-linkers with different spacer arms and chemistries have inherently different masses and can give insight into distance constraints and thus highlight networks of nearby residues. (2) The mass of the protein complex is not limiting because proteolysis precedes mass measurement, resulting in peptides that are tractable for LC-MS/MS analysis. (3) Only nanomoles, and in some cases as little as femtomoles, of protein are needed. (4) Cross-linking is conducted in solution, therefore flexible regions of proteins can undergo any necessary disorder-to-order transitions in order to form intermolecular interactions (10, 11).

Although chemical cross-linking-MS is a powerful approach to identifying protein binding domains; it is also a difficult one. The major problem associated with cross-linking mass spectrometry is that it increases the complexity of the sample by orders of magnitude. Take for example, a 10 kDa protein, which would produce roughly ten 1 kDa peptides following trypsin proteolyis. After intramolecular cross-linking, however, the number of potential cross-linked peptides increases from 10 to 10! (~3.5 million). If intermolecular cross-linking with an entire proteome is considered, this number becomes astronomical. In either case, traditional methods for matching an experimental mass to database derived theoretical masses are no longer sufficient, and novel techniques are required to reduce the complexity (e.g., purification of proteins and the use of isotopically labeled cross-linkers). The use of isotopically labeled cross-linkers allows the experimenter to discern which of the “peaks” in a mass spectrum arise from cross-linked peptides, so that they may concentrate efforts on these species (11, 12).

In addition to cross-linking-MS other strategies exist, of which we mention a few, to identify protein intermolecular interactions such as traditional proteomic strategies. For example, coimmunoprecipitation or pull down assays can be used in combination with denaturing or 2D gel electrophoresis and mass spectrometry to identify protein–protein interactions (reviewed in (13)). These proteomic studies can also be performed on a large scale, or high throughput, using such things as tandem-affinity purification (TAP) mass spectrometry (14, 15). Alternatively, techniques such as stable isotopic amino acids in cell culture (SILAC) and immunoprecipitation (IP) can be used to identify protein binding partners where isotopic distributions are used to rule out background interactions (16).

Here, we present a traditional cross-linking and mass-spectrometry approach, in which we use heavy water (18O) as an isotopic label (17, 18). In order to obtain detailed information about binding domains such as residues involved and their proximity to each other cross-linking is advantageous. Specifically, cross-links between two peptides within the same protein provide distance/structural constraints, whereas those between two peptides in different proteins (including respective monomers of oligomeric proteins) provide a region of intermolecular interaction or binding (11, 19).

2. Materials

Use HPLC grade reagents (water, acetonitrile, etc.) for all steps following the SDS-PAGE.

2.1. Cross-Linking

EDC (1-ethyl-3-[3-dimethylaminopropyl] carbodiimide) and sulfo-NHS (both obtained from Thermo Pierce) are prepared as 0.1 M stocks. To make a 0.1 M stock of EDC dissolve 1.6 g EDC in milliQ water and to make a 0.1 M stock of sulfo-NHS dissolve 2.2 g sulfo-NHS in DMSO.

Activation Buffer: 0.1 M MES, pH 6.0, 0.1 M sodium chloride (Dissolve 2.0 g MES and 0.6 g sodium chloride in 100 mL milliQ water).

2.2. Sample Preparation for Mass Spectrometry

Precast 16 % acrylamide SDS PAGE (Novex; Invitrogen). Lower percentages of acrylamide may be used for larger proteins, and user-casting of gels is optional.

SDS Sample Buffer: Add 2.5 mL 0.5 M Tris–HCl, pH 6.8; 2 mL glycerol; 4 mL 10 % SDS; 0.5 mL 0.1 % (w/v) Bromophenol blue; 0.5 mL 2-mercaptoethanol; and 0.5 mL milliQ water.

Coomassie Brilliant Blue Stain. Add 100 mL of glacial acetic acid to 450 mL of milliQ water, dissolve 3 g of Coomassie brilliant blue R250 in 450 mL of methanol, combine the two and filter-sterilize.

Destain: 40 % methanol, 10 % glacial acetic acid, 50 % milliQ water. To make 2 L combine 800 mL of methanol, 200 mL of glacial acetic acid, and 1,000 L of milliQ water. Mix.

Heavy Water (1H2 18O): Cambridge Isotopes (product number: OLM-240-97).

8 ng/μL Trypsin (Princeton Separations; EN-151).

Wash buffer: 50 mM ammonium bicarbonate in 50 % ethanol. Dissolve 0.4 g of ammonium bicarbonate in 50 mL milliQ water and 50 mL ethanol.

100 % HPLC grade ethanol (sigma).

50 mM ammonium bicarbonate and 10 mM DTT: Add 101.7 mg of DTT to 10 mL 50 mM ammonium bicarbonate, pH 8.0. Critical Step: Make shortly before use.

55 mM iodoacetamide in 50 mM ammonium bicarbonate, pH 8.0: Add 15.4 mg of iodoacetamide to 10 mL 50 mM ammonium bicarbonate. Critical Step: Make shortly before use.

Extraction buffer: 50 mM ammonium bicarbonate buffer, pH 8.0 and 50 % N, N-dimethyl formamide.

2 % acetonitrile, 0.1 % TFA. To make a 50 mL stock, dilute 1 mL 100 % acetonitrile, 0.1 % TFA (sigma) into 49 mL of HPLC water, 0.1 % TFA (sigma).

Omix C18 Tip (Agilent).

50 % acetonitrile. Dilute 50 mL HPLC grade 100 % acetonitrile (sigma) with 50 mL HPLC grade water (Sigma) and store in a glass vial.

50 % acetonitrile, 0.1 % TFA. Dilute 50 mL HPLC grade 100 % acetonitrile, 0.1 % TFA (Sigma) with 50 mL HPLC grade water, 0.1 % TFA (Sigma) and store in a glass vial.

0.1 % TFA.

2.3. Mass Spectrometry and Data Analysis

Any mass spectrometer. The experiments shown here employ MALDI-TOF Microflex (Bruker Daltonics) and a 9.4 T Apex MALDI-ESI-Qe-FTICR (Bruker Daltonics).

10 mg/mL α-cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid matrix (α-cyano) in 50 % acetonitrile, 0.1 % TFA. Weigh approximately 40 mg of α-cyano and resuspend in 40 μL 50 % acetonitrile, 0.1 % TFA.

Mobile phase: 100 % acetonitrile, 0.1 % FA and HPLC water, 0.1 % FA (Sigma).

Solid phase: NS-AC-10-C18 Biosphere C18 5 μm column (Nanoseparations).

2.4. Data Analysis

Flex Analysis (Bruker).

GPMAW (General Protein Mass Analysis for Windows) (Lighthouse Data).

Data Analysis (Bruker).

ProteinProspector (UCSF; http://prospector.ucsf.edu/prospector/mshome.htm).

3. Methods

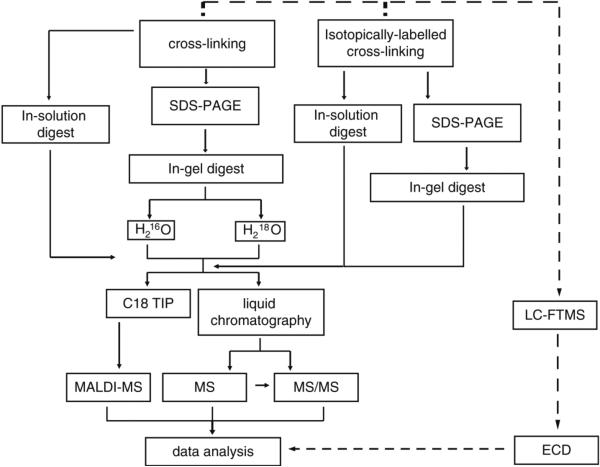

Be sure to dispose of all hazardous chemicals appropriately. Be sure to wear the appropriate personal protective equipment as outlined in MSDS. Wear gloves to avoid keratin contamination in mass spectrometric analysis. A work flow of mass spectrometry analysis of protein binding is outlined in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Mass spectrometry analysis of protein binding work-flow.

3.1. Cross-Linking

Dilute protein(s) of interest to approximately 1 mg/mL in 50 μL activation buffer. If the stock protein concentration is approximately 1 mg/mL to start dialyze into activation buffer or buffer exchange using size exclusion chromatography.

Add 1 μL 0.1 M EDC stock, giving a final concentration of 2 mM, and 2.5 μL 0.1 M sulfo-NHS, giving a final concentration of 5 mM, to the protein solution (see Note 1). Vortex the samples slightly and centrifuge at 3,000 RPM (837 rcf) for 30 s.

Incubate the cross-linking reaction at room temperature for at least 15 min (see Note 2). The extent (or completeness) of cross-linking can be monitored using MALDI-TOF or SDS PAGE analysis.

3.2. Sample Preparation: SDS PAGE and In-Gel Digest

Incubate a non-cross-linked control and all cross-linked samples with an equal volume of 2× sample loading buffer containing 2-mercaptoethanol at 95°C for 5 min, which quenches the cross-linking reaction.

Load 10–100 μL sample (if using 100 mL load into ten different lanes; 10 μL per lane) onto a 16 % SDS PAGE gel and run at 200 V until the dye front is a few centimeters from the bottom of the gel (approximately 45 min for a mini-gel apparatus).

Following electrophoresis, pry the plates apart using a spatula, remove the gel taking caution not to tear it, and stain in a plastic container with Coomassie brilliant blue stain for a few hours on a rocker (see Note 3).

Decant the Coomassie stain (save for reuse) and destain the gel in 50 % water, 40 % methanol and 10 % acetic acid in the same plastic container while will rocking over night. Change destain as needed until the gel is completely destained.

Place the destained gel on a solid glass/plastic surface that has been wiped down with 100 % acetonitrile and excise each band of interest using a new razor blade for each unique complex isolated (alternatively wipe clean the razor blade with 100 % acetonitrile between each use).

Cut each excised band into smaller pieces and place in a 1.5-mL eppendorf tube (precleaned with acetonitrile and methanol) for in-gel trypsin digestion (20) (see Note 4).

Wash gel slices twice with 50 mM ammonium bicarbonate in 50 % ethanol at room temperature. Add enough 50 mM ammonium bicarbonate in 50 % ethanol to each respective eppendorf tube to completely cover the gel slices (typically 50–100 μL), pipet up and down a few times, and aspirate using a pipette. Alternatively, gel slices can be vortexed to wash and it is not necessary to remove all the Coomassie stain from the gel slices.

Shrink gel slices by adding enough 100 % ethanol to cover them (typically 50–100 μL), aspirate using a pipette, and then incubate for 1 h at 56°C with approximately 50 μL 50 mM ammonium bicarbonate containing 10 mM DTT.

Warm the gel slices to room temperature, aspirate the DTT solution, and incubate with 55 mM iodoacetamide for 30 min in the dark.

Aspirate the iodoacetamide, wash using 50 mM ammonium bicarbonate in 50 % ethanol, shrink using 100 % ethanol, and dry using a Vacufuge (speedvac).

Split each respective gel slice into two tubes and digest overnight at 37°C with 1 μL 8 ng/μL Trypsin in the presence of 16O or 18O water, respectively (see Note 5).

Extract peptides using 50 μL 50 mM ammonium bicarbonate and 50 % N, N-dimethyl formamide.

Evaporate peptides to dryness using a speedvac (Vacufuge) and resuspend in 10 μL of 2 % acetonitrile, 0.1 % trifluoroacetic acid.

Extract peptides from the 16O digest and mix with peptides extracted from the 18O digest.

3.3. C18 Purification and MALDI-MS

Purify the above peptide samples using a 10 μL Omix C18 Ziptip (Varian/Agiliant).

Prewash the C18 Omix tip with 100 % acetonitrile and equilibrate with 0.1 % TFA.

To bind the peptides to the C18 tip, aspirate peptides approximately 30 times and any unbound or weakly bound peptides are removed by three 10 μL 0.1 % TFA washes.

Elute peptides by aspirating 5 μL of 50 % acetonitrile, 0.1 % TFA, three times into an eppendorf tube.

Then wash the C18 tip with 100 % acetonitrile and reuse.

Make a 10 mg/mL α-cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid (HCCA, α-cyano) (Sigma) by measuring out 40 mg of HCCA and diluting it in 40 μL of 50 % acetonitrile, 0.1 % TFA.

Spot 1 μL of the C18 tip eluate on a MALDI-TOF target with 1 μL of HCCA and air dry (or alternatively dried using a bench top fan).

Load the MALDI-TOF target into a Bruker Daltonics Microflex operated in reflectron mode.

Calibrate the MALDI-TOF using a peptide calibration standard (Bruker) with each use.

Spectra are the average of 500–1,000 laser shots and are collected using 50–70 % laser power.

Collect data over a range of 400–6,000 m/z and analyze using Flex Analysis software (Bruker Daltonics). Data are collected to 6,000 m/z in order to be sure we isolate any potentially large cross-linked peptides.

3.4. LC-MS/MS

Aspirate the digested sample (1 μL), no C18 tip purification, into an Eksigent 2D UPLC or Proxeon 1D HPLC system onto a NS-AC-10-C18 Biosphere C18 5 μm column (see Note 6).

The following gradient is used to elute peptides: 3–50 % buffer B for 30 min, 50–95 % buffer B for 7 min, 95 % buffer B for 5 min, 95–3 % buffer B for 1 min, and 3 % buffer B for 15 min. Buffer A is HPLC water + 0.1 % FA and buffer B is acetonitrile + 0.1 % FA (both Sigma).

Eluted peptides from the above C18 column are introduced into a 9.4 T FTICR (Bruker Daltonics) using a nanospray source.

Collect mass spectra (MS data) during the elution using the Apex Control Expert software (Bruker Daltonics) in chromatography mode over the length of the gradient (approximately 70 min).

Data dependent MS/MS data are collected using collision-induced dissociation (CID). One full scan (MS) is followed by MS/MS product ion spectra of the four most intense ions and sequenced; once an ion is selected for MS/MS analysis it is added to an exclusion list to prevent it from being selected numerous times.

3.5. Data Analysis

Use GPMAW (General Protein Mass Analysis for Windows) (Lighthouse Data) software for the prediction of theoretical m/z's for both cross-linked and non-cross-linked samples (see Note 7).

Analyze MALDI-TOF data using Flex Analysis software (Bruker Daltonics) and FTICR data using Data Analysis software (Bruker Daltonics).

Analyze each individual sample (data set) and generate a mass list of monoisotopic masses.

- Identify peptides and cross-linked peptides using the following criteria:

- Trypsin-specific cleavages are present (arginine or lysine).

- Contain a potentially cross-linkable residue. For example, a lysine would be present in both peptides involved in the cross-link if an amine cross-linker is used.

- m/z specific to a cross-linked sample.

- The m/z is reproducibly observed in duplicate or triplicate experiments.

- Intramolecular cross-links are identified by the presence of a unique m/z in monomer alone cross-linked samples.

- Intermolecular cross-links are seen in only Protein A and B cross-linked samples.

- Two water molecules are added per peptide in trypsin digests. Therefore, for a non-cross-linked peptide the m/z will shift +4 Da in the presence of heavy water and for a cross-linked peptide the m/z will shift +8 Da in the presence of heavy water (see Fig. 2).

- When possible, MS/MS data provides sequence data for a cross-linked peptide. Cross-linking complicates MS analysis, and thus obtaining MS/MS sequence data of a cross-linked peptide is often not possible; however, the reproducibility and heavy water label is sufficient to confirm cross-linked peptides.

- Two important criteria above being the reproducibility of the data and the presence of a +4 Da shift for a peptide and +8 Da shift for a cross-linked peptide.

After identification of cross-links using the above criteria, map the data back onto the respective primary structure (sequence) of each respective protein, thus highlighting the binding domains.

Fig. 2.

Heavy water labeled peptides and cross-linked peptides. (a) Mass spectra of a peptide; box zoomed in (b). (b) An unlabelled m/z at 1,380.7 and its labeled counterpart at 1,384.7; the shift in mass of four indicates a non-cross-linked peptide. (c) Mass Spectra of a cross-linked peptide (box; zoomed in (d)). Analyzing the spectra by hand allows for the majority of cross-linked pairs to be identified. (d) An unlabelled m/z at 2,156.1 and its labeled counterpart at 2,164.5; the shift in mass of eight indicates a cross-linked peptide. The cross-linking complicates the spectral analysis; however, it is still possible to distinguish the pair of related m/z values based on the isotopic label.

Fig. 3.

Noncovalent Interactions using the FTICR. (Top) Spectra of protein alone. (Bottom) Protein incubated with a panel of small molecules. The addition of a new peak indicates protein–compound complex (noncovalent interaction).

Acknowledgement

This work was supported in part by a National Institutes of Health R21 (to J.N.A.) (1R21NS071256), R21 (to C.A.S.) (R21 A1067021), P01 (to C.A.S.) (P01 GM091743), GM 32415 and GM 26788 (to G.A.P. and D.R.), and Fidelity Biosciences Research Initiative (to G.A.P. and D.R.).

Footnotes

Cross-linking: multiple cross-linkers with different spacer arms can be used to give an idea of the distance at which one residue is from another.

Cross-linking can be performed on ice or at 4°C; however, the cross-linking reaction is slowed and therefore incubation times should be at least an hour and preferably overnight. In addition, if an SDS-PAGE is not run, 2-mercaptoethanol can be used to quench the cross-linking reaction.

Silver staining is not as amenable to mass spectrometry analysis as Coomassie staining; therefore, if possible it should not be used.

If the samples being tested are pure enough, an in-solution trypsin digest can be preformed instead of and in-gel trypsin digest.

Isotopically labeled cross-linkers/biotinylated cross-linkers can be used instead of heavy water as a label to aide in cross-linked peptide identification (e.g., deuterated cross-linkers—Pierce).

Samples that have been C18 tip purified should be dried to completeness using a speed vac (Vacufuge) and resuspended in 10 μL of 2 % acetonitrile, 0.1 % trifluoroacetic acid prior to LC-MS/MS analysis. This is done because the ZipTip elution buffer is 50 % ACN, 0.1 % TFA which will prevent peptide binding to the C18 LC column.

Peptides and cross-links are identified using Data Analysis software (Bruker Daltonics) and exported to a generic mascot file. The MASCOT file is uploaded into the MASCOT search engine selecting none as the enzyme, NCBIr as the database, with a 1.2 Da (MS error tolerance) and a 0.6 Da (MS/MS error tolerance). Cross-linked and non-cross-linked sample data are compared and m/z's unique to the cross-linked sample are analyzed further using MS Bridge (ProteinProspector, UCSF, http://prospector.ucsf.edu/prospector/mshome.htm) with the specific cross-linker molecular weight and sequence inputed by the user. MS Bridge performs an in silico digest of a cross-linked protein generating m/z's for theoretical peptides and cross-linked peptides taking into account the molecular weight of the cross-linker. Potential cross-linked peptides can be further characterized using extracted ion chromatograms and MS/MS data.

One can also detect noncovalent binding of proteins and compounds using “soft ionization” techniques (electrospray ionization) and the Fourier transform mass spectrometer (FTMS) (reviewed in (21)). Purified protein is incubated with four unique compounds for 30 min on ice. After incubation the protein-compound complex is directly infused into a Bruker Daltonics. 4 T FTICR using a nanosource. The protein–compound complex is sprayed in 10 mM ammonium acetate, pH 6.8 with a skimmer one voltage between 20 and 40 V; 75 spectra are averaged together and the protein alone control is compared to the protein–compound spectra for the addition of any new peaks consistent with the molecular weight of a complex (see Fig. 3).

In addition to cross-linking and noncovalent binding one can also use a “footprinting” type of experiment (22). First, biotinylate protein A and B, separately, and detect sites of biotinylation using LC-MS/MS. Then incubate protein A with protein B for 30–60 min (or longer) and then biotinylate and identify sites of biotinylation using LC-MS/MS. Any sites of biotinylation in the complex that are lost indicate a binding surface.

References

- 1.Dunker AK, et al. Intrinsically disordered protein. (Translated from eng). J Mol Graph Model. 2001;19(1):26–59. doi: 10.1016/s1093-3263(00)00138-8. (in eng) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yates JR, Ruse CI, Nakorchevsky A. Proteomics by mass spectrometry: approaches, advances, and applications. (Translated from eng). Annu Rev Biomed Eng. 2009;11:49–79. doi: 10.1146/annurev-bioeng-061008-124934. (in eng) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Back JW, de Jong L, Muijsers AO, de Koster CG. Chemical cross-linking and mass spectrometry for protein structural modeling. (Translated from eng). J Mol Biol. 2003;331(2):303–313. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(03)00721-6. (in eng) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eyles SJ, Kaltashov IA. Methods to study protein dynamics and folding by mass spectrometry. (Translated from eng). Methods. 2004;34(1):88–99. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2004.03.015. (in eng) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Farmer TB, Caprioli RM. Determination of protein-protein interactions by matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization mass spectrometry. (Translated from eng). J Mass Spectrom. 1998;33(8):697–704. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9888(199808)33:8<697::AID-JMS711>3.0.CO;2-H. (in eng) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kalkhof S, Ihling C, Mechtler K, Sinz A. Chemical cross-linking and high-performance Fourier transform ion cyclotron resonance mass spectrometry for protein interaction analysis: application to a calmodulin/target peptide complex. (Translated from eng). Anal Chem. 2005;77(2):495–503. doi: 10.1021/ac0487294. (in eng) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schulz DM, Ihling C, Clore GM, Sinz A. Mapping the topology and determination of a low-resolution three-dimensional structure of the calmodulin-melittin complex by chemical cross-linking and high-resolution FTICRMS: direct demonstration of multiple binding modes. (Translated from eng). Biochemistry. 2004;43(16):4703–4715. doi: 10.1021/bi036149f. (in eng) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sinz A. Chemical cross-linking and mass spectrometry for mapping three-dimensional structures of proteins and protein complexes. (Translated from eng). J Mass Spectrom. 2003;38(12):1225–1237. doi: 10.1002/jms.559. (in eng) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Trester-Zedlitz M, et al. A modular cross-linking approach for exploring protein interactions. (Translated from eng). J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125(9):2416–2425. doi: 10.1021/ja026917a. (in eng) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sinz A. Chemical cross-linking and mass spectrometry to map three-dimensional protein structures and protein-protein interactions. (Translated from eng). Mass Spectrom Rev. 2006;25(4):663–682. doi: 10.1002/mas.20082. (in eng) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Auclair JR, et al. Mass spectrometry analysis of HIV-1 Vif reveals an increase in ordered structure upon oligomerization in regions necessary for viral infectivity. (Translated from eng). Proteins. 2007;69(2):270–284. doi: 10.1002/prot.21471. (in eng) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Leitner A, et al. Probing native protein structures by chemical cross-linking, mass spec-trometry, and bioinformatics. (Translated from eng). Mol Cell Proteomics. 2010;9(8):1634–1649. doi: 10.1074/mcp.R000001-MCP201. (in eng) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pandey A, Mann M. Proteomics to study genes and genomes. (Translated from eng). Nature. 2000;405(6788):837–846. doi: 10.1038/35015709. (in eng) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gavin AC, et al. Functional organization of the yeast proteome by systematic analysis of protein complexes. (Translated from eng). Nature. 2002;415(6868):141–147. doi: 10.1038/415141a. (in eng) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ho Y, et al. Systematic identification of protein complexes in Saccharomyces cerevisiae by mass spectrometry. (Translated from eng). Nature. 2002;415(6868):180–183. doi: 10.1038/415180a. (in eng) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Blagoev B, et al. A proteomics strategy to elucidate functional protein-protein interactions applied to EGF signaling. (Translated from eng). Nat Biotechnol. 2003;21(3):315–318. doi: 10.1038/nbt790. (in eng) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Back JW, et al. Identification of cross-linked peptides for protein interaction studies using mass spectrometry and 18O labeling. (Translated from eng). Anal Chem. 2002;74(17):4417–4422. doi: 10.1021/ac0257492. (in eng) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yao X, Freas A, Ramirez J, Demirev PA, Fenselau C. Proteolytic 18O labeling for comparative proteomics: model studies with two serotypes of adenovirus. (Translated from eng). Anal Chem. 2001;73(13):2836–2842. doi: 10.1021/ac001404c. (in eng) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Auclair JR, Boggio KJ, Petsko GA, Ringe D, Agar JN. Strategies for stabilizing super-oxide dismutase (SOD1), the protein destabilized in the most common form of familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. (Translated from Eng). Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107(50):21394–21399. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1015463107. (in eng) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shevchenko A, Tomas H, Havlis J, Olsen JV, Mann M. In-gel digestion for mass spec-trometric characterization of proteins and proteomes. (Translated from eng). Nat Protoc. 2006;1(6):2856–2860. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.468. (in eng) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McCullough BJ, Gaskell SJ. Using electrospray ionisation mass spectrometry to study non-covalent interactions. Combo Chem High Throughput Screen. 2009;12(2):203–211. doi: 10.2174/138620709787315463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kvaratskhella M, Miller JT, Budihas SR, Pan-nell LK, Le Grice SFJ. Identification of specific HIV-1 reverse transcriptase contacts to the viral RNA:tRNA complex by mass spectrometry and a primary amine selective reagent. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99(25):15988–15993. doi: 10.1073/pnas.252550199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]