Summary

Caveolae are flask-shaped membrane invaginations present in most mammalian cells. They are distinguished by the presence of a striated coat composed of the protein, caveolin. Caveolae have been implicated in numerous cellular processes, including potocytosis in which caveolae are hypothesized to co-localize with folate receptor α and participate in folate uptake. Our laboratory has recently localized folate receptor α to the basolateral surface of the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE). It is present also in many other cells of the retina. In the present study, we asked whether caveolae were present in the RPE, and if so, whether their pattern of distribution was similar to folate receptor α. We also examined the distribution pattern of caveolin-1, which can be a marker of caveolae. Extensive electron microscopical analysis revealed caveolae associated with endothelial cells. However, none were detected in intact or cultured RPE. Laser scanning confocal microscopical analysis of intact RPE localized caveolin-1 to the apical and basal surfaces, a distribution unlike folate receptor α. Western analysis confirmed the presence of caveolin-1 in cultured RPE cells and laser scanning confocal microscopy localized the protein to the basal plasma membrane of the RPE, a distribution like that of folate receptor α. This distribution was confirmed by electron microscopic immunolocalization. The lack of caveolae in the RPE suggests that these structures may not be essential for folate internalization in the RPE.

Introduction

Folate is a water-soluble vitamin that is essential for the synthesis of purines, pyrimadines, and some amino acids. It is, therefore, necessary for the survival of all cells. Folate and its derivatives are lipophobic, bivalent anions that do not diffuse across biological membranes, thus, they require specific transport mechanisms to enter cells. Recently two folate transport proteins, folate receptor α and reduced-folate transporter-1, have been identified in mammalian retinal pigment epithelium (RPE). Folate receptor α, a glycosylphosphatidylinositol-linked protein (Lacey et al. 1989, Lee et al. 1992, Verma et al. 1992, Sun & Antony 1996), was localized to the basolateral surface (Smith et al. 1999a). Reduced-folate transporter-1, a typical facilitative transmembrane protein with 12 transmembrane domains (Sirotnak & Tolner 1999), was present on the apical membrane (Huang et al. 1997, Chancy et al. 2000). Additional studies have demonstrated that, in the RPE (Chancy et al. 2000), as in other cell types (Sirotnak & Tolner 1999), reduced-folate transporter-1 transports folate in a pH-dependent manner and is regulated by nitric oxide (Smith et al. 1999b).

Owing to the mobile nature of reduced-folate transporter-1 (Ratnam & Freisheim 1992), the transporter is capable of mediating bi-directional flux of folate. Folate receptor, on the other hand, mediates unidirectional flux of folate following internalization of the receptor-folate complex in a manner similar to other ligand-receptor processes. In the early nineties, it was reported that folate receptor internalized folate without entering the clathrin-coated pit endocytic pathway (Rothberg et al. 1990). Its extracellular location led to the proposal of a novel mechanism of folate transport termed potocytosis. This model of folate transport hypothesized that folate receptors were clustered within caveolae and that this organization was required for folate uptake into cells. According to this hypothesis, when caveolae are open to the extracellular environment, folate receptor binds folate. Following binding, the caveolae close off with subsequent acidification of the caveolar compartments. The resulting acid pH within the caveolae releases folate from the receptor and also provides the driving force for the transfer of folate from the caveolae to the cytoplasm via a carrier-mediated process (Anderson et al. 1992, 1993, Rothberg et al. 1992, Smart et al. 1994). Increasing evidence suggests, however, that folate receptors may not associate with caveolae, but may be located on the plasma membrane independent of the caveolar structure. Studies in cultured cells suggested that the association of folate receptor with caveolae may have been an artifact of the electron microscope experiments that led to the potocytosis hypothesis (Mayor et al. 1994, Wu et al. 1997). These later studies showed that although folate receptors were clustered on the plasma membrane, they were not associated with the caveolar structure (Wu et al. 1997).

In our ongoing efforts to elucidate the mechanisms of folate transport in the RPE, we asked whether caveolae were present in this tissue. While these structures were easily detected in endothelial cells of the inner retina, they were never observed in intact or cultured RPE. Since the protein, caveolin-1 can be used as a marker of caveolae, we examined its pattern of distribution in intact and cultured RPE. Caveolin-1 has been detected in retinal endothelial cells (Gardiner & Archer 1986a,b, Feng et al. 1999), but its presence has not been examined in the RPE. Our data supported the observations of Gardiner and Archer (1986a,b) and Feng et al. (1999). Caveolin-1 was identified in retinal endothelial cells as well as the RPE. Its distribution was not as widespread in retina as that of folate receptor α, which was detected in several layers of the retina (Smith et al. 1999a). In the RPE, caveolin-1 was present on the apical and basal surfaces, though folate receptor α was only detected on the basal surface (Smith et al. 1999a).

Materials and methods

Animals

Five-to-six week old albino (ICR) mice were obtained from Harlan Sprague-Dawley, Indianapolis, IN. Care and use of the animals adhered to the principles set forth in the DHEW Publication, NIH 80-23 ‘The Guiding Principles in the Care and Use of Animals.’

Tissue culture

ARPE-19 cells (ATCC, Manassas, VA), a human RPE cell line, were used for these experiments. Cultures were maintained at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2. Cells were grown in 75 cm3 flasks and maintained with Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium (DMEM): nutrient mixture F12 (Gibco BRL, Grand Island, NY) supplemented with 10% foetal bovine serum (FBS, Sigma, St. Louis, MO), 100 U/ml penicillin and 100 μg/ml streptomycin (Gibco BRL). Cultures were passaged by dissociation in 0.25% (w/v) trypsin (Gibco BRL) in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). After trypsinizing, ARPE-19 cells were seeded on Nunc chamber slides (Fisher, Norcross, GA) coated with 5 μg/cm2 mouse laminin (Collaborative Biomedical Products, Bedford, MA). Laminin promotes growth, adhesion and protein synthesis in epithelial cells in vivo (Timpl et al. 1979, Sugrue & Hay 1981, Vlodavsky & Gospodarowicz 1981, McGarvey et al. 1984, Kleinman et al. 1985) and as a component of Bruch’s membrane (Kono et al. 1983, Turksen et al. 1985, Sramek et al. 1985), may play an important role in RPE differentiation and polarity (Heth et al. 1987). In some experiments, ARPE-19 cells were seeded on laminin-coated (5 μg/cm2) Millipore 0.4 μm polycarbonate membrane inserts (Fisher). These cells were maintained with DMEM: F12 supplemented with 1% FBS and 100 U/ml penicillin and 100 μg/ml streptomycin. The serum content of the medium was decreased from 10% to 1% to promote differentiation of the cells (Dunn et al. 1996). To further encourage proper differentiation, cells were cultured for at least 4 weeks prior to each experiment (Dunn et al. 1996).

Electron microscopical analysis for caveolae in intact and cultured RPE

Eyes from albino mice were enucleated and fixed for 1 h at room temperature in 2% paraformaldehyde–2% glutaraldehyde (Electron Microscopy Sciences, Ft. Washington, PA) in 0.1 M cacodylate buffer in sucrose (pH 7.2). Eyes were punctured at the limbus and returned to the fixative for an overnight fixation. After post-fixation with 4% osmium tetroxide (Electron Microscopy Sciences), the eyes were washed with cacodylate buffer and embedded in Embed 812–Araldite-502 mixture (Epon) (Polysciences, Warrington, PA). A graded ethanol series to 100% was used to dehydrate the tissue, which was then followed by infiltration with 1 : 1 v/v Epon–propylene oxide (Electron Microscopy Sciences) at room temperature for 1 h. Subsequently, fresh Epon was added and polymerization carried out overnight at 60 °C. ARPE-19 cells and the polycarbonate membranes on which they were growing were fixed for 1 h at room temperature in 2% paraformaldehyde–1% glutaraldehyde and were embedded in the same fashion as the intact tissue. Intact tissue and cell monolayers were examined extensively for the presence of caveolae.

Light microscopic immunolocalization of caveolin-1 in intact RPE

To determine the presence of caveolin-1 in intact RPE, light microscope immunolocalization was used. Eyes from adult albino mice were enucleated, frozen immediately in Tissue-Tek OCT (Miles Laboratories, Elkhart IN) and sectioned at 10 μm thickness. Sections were fixed in ice-cold acetone for 5 min. Endogenous peroxidase activity was quenched by incubating the specimens for 5 min with 3% hydrogen peroxide. This reagent and the additional reagents used to visualize the primary antibody were supplied as part of the LSAB kit-Peroxidase (DAKO Corp. Carpinteria, CA) and the assay was performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions. After the sections were blocked for 10 min with 4% goat serum, they were incubated for 1 h with either an antibody against folate receptor α (kindly provided by Dr. Manohar Ratnam, Medical College of Ohio, Toledo, OH) (Ratnam et al. 1989) at a dilution of 1 : 100 or an affinity-purified antibody against caveolin-1 at a dilution of 1 : 1600 (Transduction Laboratories, Lexington KY). Negative control sections were treated identically with buffer only or normal rabbit serum (Sigma) used in place of the primary antibody. Sections were incubated with the biotinylated anti-rabbit IgG for 10 min at room temperature, rinsed, incubated with streptavidin-conjugated horseradish peroxidase for 10 min, rinsed, incubated with AEC chromogen solution (3% 3-amino-9-ethylcarbazole in N,N-dimethylformamide) at room temperature and rinsed with deionized water. The slides were not counterstained so that the reddish brown-coloured precipitate could be visualized in the sections. Sections were viewed using a Zeiss Axiophot microscope. Additional sections, processed through the same buffers, were subjected to standard haematoxylin–eosin staining to permit visualization of the retinal cellular layers.

Western blot analysis of caveolin-1 in cultured human ARPE-19 cells

To determine the presence of caveolin-1 in ARPE-19 cells, Western blot analysis was performed as previously described with minor modifications (Islam & Akhtar 2000). Cultured human ARPE-19 cells were washed with PBS and lysed with the addition of cold lysis buffer (50 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.4, containing 1% Triton-X-100, 10 mM EDTA, 2 mM Na3VO4, 0.5% deoxycholate, 10 mM sodium pyrophosphate and 50 mM NaF). Cells were scraped off the flask and passed through a 26-gauge needle several times to create a homogeneous mixture. Cells were sonicated for 15–20 s and the cell debris was removed by centrifugation at 10,000 rpm for 15 min. Protein concentrations in the supernatant were determined according to the method of Lowry et al. (1951). Equivalent amounts of protein from the total cell lysate were boiled in Laemmli’s buffer for 5 min and analysed by 10% SDS-PAGE (Laemmli 1970). After transferring the separated proteins onto nitrocellulose membranes, the membranes were blocked for 2 h at room temperature with Tris-buffered saline-0.1% Tween-20 containing 5% non-fat milk. The membranes were incubated for 2 h with polyclonal antibodies (0.5 μg/ml) against caveolin-1 or reduced-folate transporter-1 (Chancy et al. 2000). The primary antibodies were followed by incubation with a secondary HRP-conjugated goat anti-rabbit antibody (1 : 3000) for 1 h. The membranes were washed and the proteins visualized using the ECL Western detection system (Amersham, Piscataway, NJ).

Laser scanning confocal microscope immunolocalization of caveolin-1 in intact and cultured RPE

To localize caveolin-1 in intact RPE, fluorescent immunohistochemical studies were performed. Eyes from adult albino mice were enucleated, frozen immediately in Tissue-Tek OCT (Miles Laboratories, Elkhart IN) and sectioned at 10 μm thickness. Cryosections were fixed in cold acetone, washed with PBS and blocked with 4% goat serum (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, West Grove PA). Sections were incubated for 3 h at room temperature followed by overnight incubation at 4 °C with either a primary antibody against the Na+,K+-ATPase (Accurate Chemical Co., Westbury NY) at a dilution of 1 : 50, an affinity purified polyclonal antibody (IgG) against caveolin-1 at a dilution of 1 : 100, or a polyclonal antibody against folate receptor α at a dilution of 1 : 50. Incubation with 0.01% normal rabbit serum served as a negative control. The Na+,K+-ATPase was used as a marker for the apical plasma membrane of the RPE cells (Miller et al. 1978, Ostwald & Steinberg 1980, Okami et al. 1990, Gundersen et al. 1991, Quinn & Miller 1992). Folate receptor α served as a marker for the basolateral plasmalemmal surface of the RPE (Smith et al. 1999a, Chancy et al. 2000). Sections were rinsed and incubated overnight at 4 °C with a fluorescein (FITC)-conjugated AffiniPure goat anti-rabbit IgG (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories) at a dilution of 1 : 100. ARPE-19 cells cultured on chamber slides were treated in a similar fashion. Cells were fixed in ice-cold methanol for 5 min, air-dried, and washed with PBS. Cells were incubated overnight at 4 °C with either an antibody against caveolin-1 at a dilution of 1 : 100 or an antibody against the Na+,K+-ATPase at a dilution of 1 : 50. After washing, cells were incubated overnight at 4 °C with a FITC-conjugated IgG antibody. Optical sectioning of the tissue was performed using a Nikon Diaphot 200 Laser Scanning Confocal Imaging System (Molecular Dynamics, Sunnyvale, CA). Images were analysed using the Image Display 3.2 software package (Silicon Graphics, Mountain View, CA).

Electron microscopical immunolocalization of caveolin-1 in intact and cultured RPE

Electron microscopical immunolocalization was used to localize the distribution of caveolin-1 in intact and cultured RPE. Eyes from adult albino mice were enucleated and fixed for 1 h at room temperature in 2% paraformaldehyde–1% glutaraldehyde (Electron Microscopy Sciences, Ft. Washington, PA) in 0.1 M cacodylate buffer in 7% sucrose (pH 7.2). Eyes were punctured at the limbus and returned to the fixative for an overnight fixation. ARPE-19 cells grown for 4 weeks on permeable membranes were fixed for 1 h at room temperature in 2% paraformaldehyde–1% glutaraldehyde. After washing, the eyes and cells were embedded in LR White (Polysciences, Warrington PA). The tissue was dehydrated with a graded ethanol series to 90% and infiltrated with LR White and 90% ethanol (2 : 1 v/v) overnight at 4 °C. Subsequently, fresh LR White was added and polymerization was carried out overnight at 55 °C. Thin sections (90 nm) were obtained, placed on Formvar-coated nickel grids (Electron Microscopy Sciences), and subjected to post embedding immunocytochemistry. After blocking with 4% normal goat serum, the sections were incubated for 6 h at room temperature with a polyclonal IgG against caveolin-1 (1 : 100), a polyclonal IgG against folate receptor α (1 : 50), or a polyclonal antibody against Na+,K+-ATPase (1 : 50). Sections were rinsed in PBS and incubated for 1 h at room temperature with an 18 nm anti-rabbit colloidal gold conjugated IgG at a dilution of 1 : 100 (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories). Sections were rinsed, stained with uranyl acetate (Electron Microscopy Sciences) and lead citrate (Electron Microscopy Sciences), and viewed with a Philips 400 transmission electron microscope (Philips, Eindhoven, The Netherlands).

Results and discussion

Electron microscopical localization of caveolae in intact retina

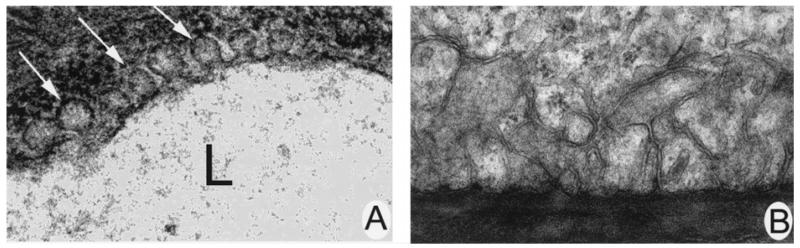

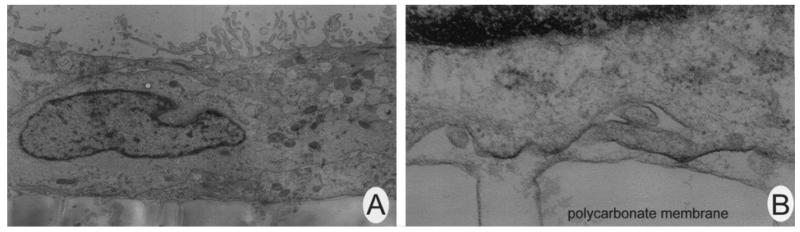

Since caveolae have been implicated in the internalization of folate receptor, we examined Epon-embedded tissues for the presence of these structures. In the retina, caveolae were associated with endothelial cells of retinal blood vessels (Figure 1A), a finding that supports the observations of Gardiner and Archer (1986a,b) and Feng et al. (1999). Exhaustive efforts to identify caveolae in the RPE were unsuccessful. Figure 1B shows a representative high power photomicrograph of the basal region of the RPE. No caveolae were identified. As the basal RPE membrane is the site of folate receptor α in these cells (Smith et al. 1999a, Chancy et al. 2000), it suggests that caveolae may not be involved in folate receptor α internalization in these cells.

Figure 1.

Electron microscopical analysis of caveolae in intact retina. (A) Electron micrograph of retinal endothelial cells with caveolae (arrows) present (60,000×). (B) Electron micrograph of representative section of basal infoldings of a RPE cell. No caveolae were identified (27,500×).

Immunolocalization of caveolin-1 in intact RPE

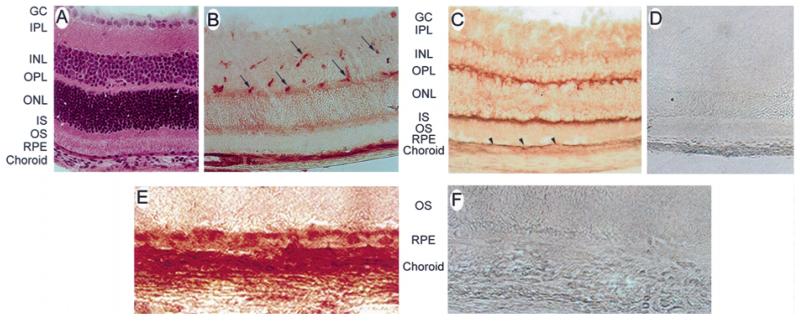

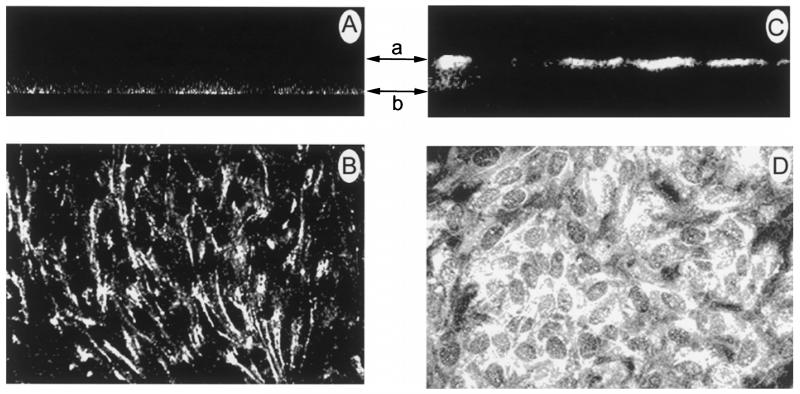

Caveolin-1 is a 22 kDa protein (Rothberg et al. 1992) which forms the striated coat (Somlyo et al. 1971, Montesano et al. 1982, Peters et al. 1985) that wraps around each caveola. Since over 90% of caveolin-1 is found associated with caveolae, it can be reliably used as a marker for the caveolar structure (Rothberg et al. 1992). To determine whether caveolin-1 was present in the RPE, non-fluorescent immunohistochemistry was performed on frozen sections of ocular tissue obtained from albino mice. Figure 2A shows a cryosection of mouse retina stained with haematoxylin and eosin for visualization of the retinal layers. Figure 2B shows a retinal cryosection incubated with an antibody against caveolin-1. The presence of the protein is indicated by dark reddish-brown staining. Caveolin-1 was detected abundantly in the retinal vasculature, as described previously (Gardiner and Archer 1986a,b, Feng et al. 1999), as well as in the RPE and choroid. It was not present in any other cells of the retina. Figure 2C shows a retinal cryosection incubated with folate receptor α. This protein was detected abundantly in the cells of the outer plexiform layer, the inner segments of the photoreceptor cells, and in the RPE. As shown previously (Smith et al. 1999a), folate receptor α is not present in the choroid. Figure 2D shows a retinal cryosection incubated with normal rabbit serum. No immunoreactivity was observed. Figure 2E shows a high magnification of mouse RPE labelled with an antibody against caveolin-1. The outer segments of the photoreceptor cells can be seen adjacent to the apical surface of the RPE. The RPE is shown resting on Bruch’s membrane, adjacent to the choroid. The intense red colour of the RPE suggests the presence of caveolin-1. Caveolin-1 is present abundantly in the choroid as well. Figure 2F shows a high magnification of a retinal cryosection incubated with normal rabbit serum. No immunoreactivity was observed. From this analysis, it is clear that caveolin-1 is present in the RPE; however, its localization to the apical or basolateral membrane is unclear. To more precisely localize caveolin-1 in the RPE cell layer, fluorescence immunolocalization techniques were used. Figure 3A shows a confocal microscope image of a cryosection of mouse RPE labelled with an antibody against caveolin-1. Caveolin-1 was present on the apical and basal plasmalemmal surfaces, as represented by the upper and lower two-headed arrows, respectively. The distribution of caveolin-1 on the basal RPE surface was uniform, whereas the distribution on the apical membrane was more punctate in appearance. This distribution differs somewhat from the exclusively basolateral localization of folate receptor α (Figure 3B). To rule out the possibility that the positive basolateral labelling was due to autofluorescence of Bruch’s membrane or RPE, we performed immunolabelling studies of the Na+,K+-ATPase as well. As shown in Figure 3C, this protein was localized only on the apical RPE membrane. No autofluorescence of basal RPE membranes or choroid was observed. A haematoxylin and eosin stained cryosection of mouse retina is shown for comparison in Figure 3D.

Figure 2.

Light immunohistochemical analysis of caveolin-1 in mouse retina. (A) Haematoxylin- and eosin-stained cryosection of mouse retina shown for comparison (400×). (B) Cryosection of mouse retina labelled with an antibody against caveolin-1 (400×). The dark reddish-brown staining is representative of caveolin-1 localization. Arrows point to blood vessels. (C) Cryosection of mouse retina labelled with antibody against folate receptor α (400×). Arrowheads point to RPE. (D) Cryosection of mouse retina labelled with normal rabbit serum in place of the primary antibody (400×). No immunoreactivity was observed. (E) High magnification of the RPE–choroid complex of a mouse retina labelled with an antibody against caveolin-1. (F) High magnification of the RPE–choroid complex of a mouse retina incubated with normal rabbit serum in place of the primary antibody. No immunoreactivity was observed (400×). Abbreviations: GC, ganglion cells; IPL, inner plexiform layer; INL, inner nuclear layer; OPL, outer plexiform layer; ONL, outer nuclear layer; IS, inner segments of the photoreceptor cells; OS, outer segments of the photoreceptor cells; RPE, retinal pigment epithelium.

Figure 3.

Laser scanning confocal microscopic localization of caveolin-1 and folate receptor α in intact mouse RPE. (A) High magnification of mouse retina incubated with an antibody against caveolin-1. The apical and basal plasma membranes of the RPE are represented by the top (a) and bottom (b) two-headed arrows, respectively. Caveolin-1 is present on the apical (arrows) and basal (arrowheads) plasmalemmal surfaces of the RPE cell. (B) High magnification of mouse retina incubated with an antibody against the folate receptor α. Note the intense bands of fluorescence on the basolateral membrane of RPE, but no immunoreactivity in the apical region. (C) High magnification of mouse retina incubated with an antibody against the Na+,K+-ATPase. As expected, an intense band of fluorescent labelling was observed on the apical surface of the RPE monolayer. (D) Haematoxylin and eosin-stained section of mouse retina shown for comparison (630×). Abbreviations: IS, inner segments; OS, outer segments; RPE, retinal pigment epithelium.

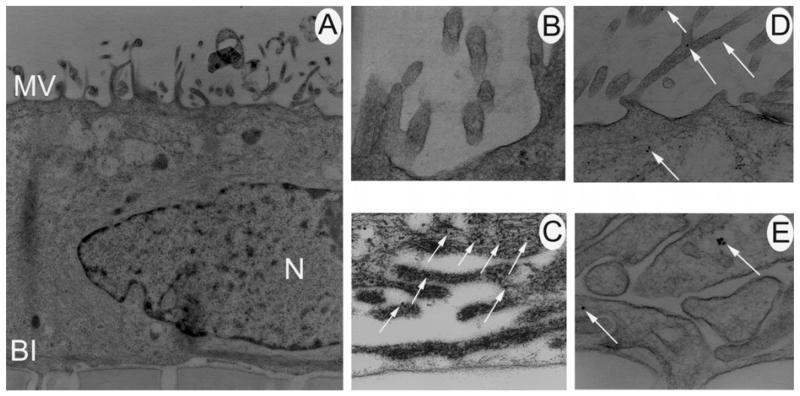

Electron microscopical analysis of caveolin-1 in intact mouse RPE

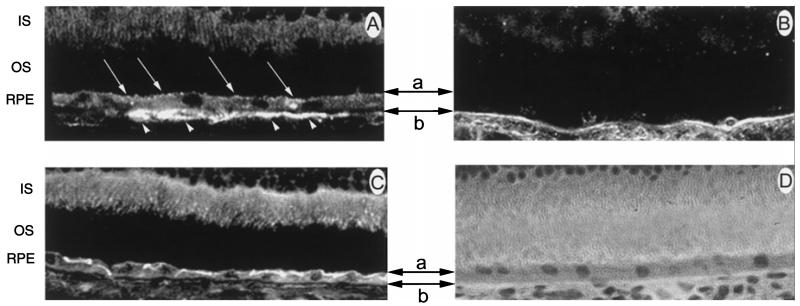

To analyse the localization of caveolin-1 further in the RPE, electron microscopical immunolocalization was performed on 90 nm sections of intact mouse retina. As with the laser scanning confocal microscope analysis, electron microscopical analysis demonstrated that caveolin-1 was present on the basolateral and apical membranes of the RPE. Figure 4A is a photomicrograph of mouse RPE depicting apical microvilli and basal infoldings for comparison to panels B–E. Figure 4B and C show higher magnifications of the apical microvilli and basolateral infoldings, respectively, of a RPE cell labelled with an antibody against caveolin-1. Detection of the primary antibody with an 18 nm colloidal gold-conjugated secondary antibody revealed that caveolin-1 was found on the apical (Figure 4B) and basal (Figure 4C) plasma membranes of the RPE cell. As positive controls, folate receptor α and the Na+,K+-ATPase were localized in the RPE. The Na+,K+-ATPase was expressed abundantly on the apical microvilli (Figure 4D) while folate receptor α was detected only on the basolateral infoldings (Figure 4E).

Figure 4.

Electron microscopical immunohistochemical analysis of caveolin-1 in mammalian retina. (A) Mouse RPE depicting apical microvilli (AM) and basal infoldings (BI). The nucleus (N) and mitochondria (M) are also visible (7700×). Panel A serves as a comparison for panels B–E, which are higher magnifications of the apical and basal plasma membranes of a RPE cell. (B) Higher magnification of apical microvilli labelled with an antibody against caveolin-1. Arrows point to gold particles indicative of positive labelling (27,500×). (C) Higher magnification of the basal infoldings of RPE labelled with an antibody against caveolin-1. Arrows point to gold particles (35,500×). (D) Higher magnification of apical microvilli labelled with antibody against the Na+,K+-ATPase (60,000×). Gold particles were abundant. (E) Higher magnification of the basolateral infoldings of a RPE cell labelled with an antibody against folate receptor α (60,000×). Gold particles were present across the membrane.

Electron microscopical analysis of caveolae in ARPE-19 cells

In studies of folate transport, cultured cells are used frequently. We sought to determine if caveolae were present in ARPE-19 cells, a well-differentiated RPE cell line. These cultured cells retain features characteristic of intact RPE including defined cell borders, a cobblestone appearance, noticeable pigmentation (Dunn et al. 1996, 1998), and the capacity to phagocytose outer segment disks (Finnemann et al. 1997). Monolayers of ARPE-19 cells, were grown on permeable membranes and analysed by electron microscopy. Figure 5A shows an electron micrograph of an ARPE-19 cell. Extensive inspection of the monolayer revealed no caveolae. Figure 5B shows a representative high power micrograph of the basal membrane of an ARPE-19 cell. No caveolae were observed.

Figure 5.

Electron microscopical analysis of caveolae in cultured human ARPE-19 cells. (A) Electron micrograph of a cultured human ARPE-19 cell grown on a permeable membrane support (4600×). (B) High magnification of a representative basal section of an ARPE-19 cell showing no caveolae (46,000×).

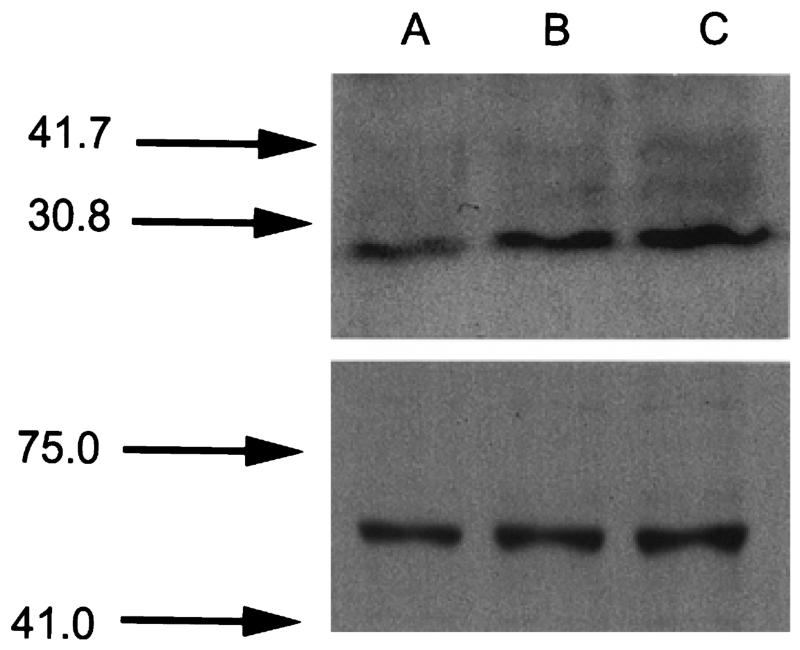

Western blot analysis of caveolin-1 in cultured human ARPE-19 cells

Western blot analysis was used to determine whether caveolin-1 was present in cultured ARPE-19 cells. The tight association between the RPE and choroid makes it difficult to isolate the RPE from intact retina. Cultured RPE cells, however, provide a relatively pure source of RPE. Western blot analysis of cultured human ARPE-19 cells demonstrated the presence of caveolin-1 (Figure 6A). As a positive control (Huang et al. 1997, Chancy et al. 2000), reduced-folate transporter-1 was also identified in these cells (Figure 6B).

Figure 6.

Western analysis of caveolin-1 in cultured human ARPE-19 cells. Proteins extracted from ARPE-19 cells were subjected to SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted as described in the text. The upper panel shows an immunoblot probed with an antibody to detect caveolin-1. The lower panel shows an immunoblot probed with an antibody to detect a protein known to be present in the RPE, reduced-folate transporter-1. Lanes A–C represent increasing protein loading amounts of 10, 20, and 30 μg, repectively.

Laser scanning confocal microscope immunolocalization of caveolin-1 in cultured ARPE-19 cells

To determine the distribution of caveolin-1 in ARPE-19 cells, laser scanning confocal microscopical immunolocalization was performed. Figures 7A and C show optical sections of cells viewed in a vertical (z, y) dimension while Figures 7B and D show optical sections of cells viewed in a horizontal (x, y) dimension. Fluorescence immunolocalization studies revealed a similar pattern of distribution for caveolin-1 (Figure 7A and B) and folate receptor α (Chancy et al. 2000) on the basal RPE surface. Figure 7A shows a vertical scan of cells incubated with an antibody against caveolin-1. Fluorescent labelling across the basolateral region of the cells is suggestive of a basolateral distribution for caveolin-1. Figure 7B shows a horizontal scan of cells incubated with antibody against caveolin-1. The ring-like fluorescence pattern is suggestive of a basolateral distribution for caveolin-1. This pattern is consistent with that shown previously for folate receptor α (Chancy et al. 2000). Interestingly, caveolin-1 was not observed on the apical surface as with the intact tissue. The specificity of this finding is illustrated in Figure 7C and D in which the Na+,K+-ATPase was detected on the apical plasma membrane. Figure 7C shows a vertical scan of cells incubated with the Na+,K+-ATPase. Fluorescent labelling was present on the apical surface, as expected. The horizontal scan (Figure 7D) revealed a dome-like fluorescence pattern, suggestive of an apical distribution.

Figure 7.

Laser scanning confocal microscope analysis of caveolin-1 distribution in cultured human ARPE-19 cells. Panels A and C are sections of cells shown in a vertical dimension (z, y). The upper and lower arrows represent the apical and basolateral surfaces, respectively. Panels B and D are sections of cells shown in a horizontal dimension (x, y). Panels A and B show cells incubated with an antibody against caveolin-1. The vertical scan (panel A) revealed a basolateral distribution for caveolin-1. A ring-like fluorescence pattern was observed in the horizontal scan (panel B), suggestive of a basolateral distribution. As a positive control, cells were incubated with antibody against the Na+,K+-ATPase. The apical band of fluorescence in the vertical scan (panel C) and the dome-like fluorescence pattern in the horizontal scan (panel D) suggests an apical distribution for the protein (630×).

Electron microscopical analysis of caveolin-1 in cultured human ARPE-19 cells

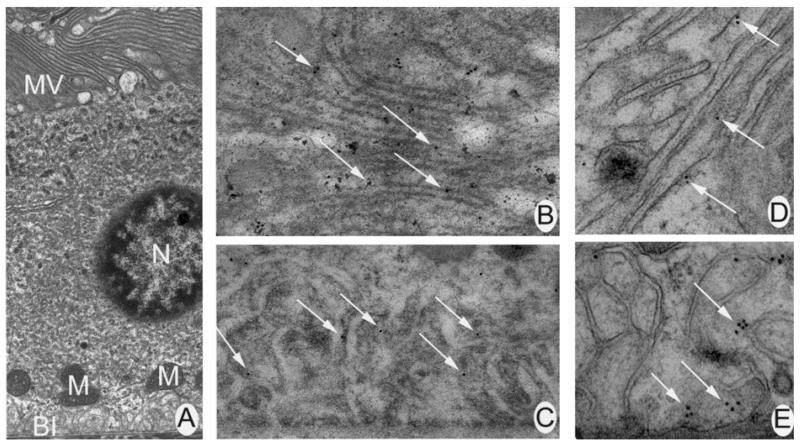

To confirm the localization of caveolin-1 in cultured human ARPE-19 cells, electron microscopical immunohistochemical assays were performed. Figures 8A shows an ARPE-19 cell with apical microvilli and basolateral infoldings. Figures 8B and C show higher magnifications of apical microvilli and basolateral infoldings, respectively, of a ARPE-19 cell incubated with an antibody against caveolin-1. Gold particles, indicative of caveolin-1 distribution, were abundant on the basolateral infoldings (Figure 8C), but were not identified on the apical surface (Figure 8B). As a positive control, the Na+,K+-ATPase and folate receptor α were localized in these cells. The Na+,K+-ATPase was localized to the apical microvilli (Figure 8D) while folate receptor α was localized to the basolateral infoldings (Figure 8E).

Figure 8.

Electron microscopical analysis of caveolin-1 in cultured human ARPE-19 cells. (A) Micrograph of an ARPE-19 cell depicting apical microvilli (AM) and basal infoldings (BI). The nucleus (N) can also be seen (7700×). Panel A serves as a comparison for panels B–E, which are higher magnifications of the apical and basal plasma membranes of a RPE cell. (B) Higher magnification of apical microvilli labelled with an antibody against caveolin-1. No gold particles were observed (60,000×). (C) Higher magnification of the basal infoldings of RPE labelled with an antibody against caveolin-1. Arrows point to gold particles (35,500×). (D) Higher magnification of apical microvilli labelled with antibody against the Na+,K+-ATPase. Gold particles were abundant (46,000×). (E) Higher magnification of the basolateral infoldings of A RPE cells labelled with an antibody against folate receptor α. Gold particles were present across the membrane (46,000×).

Caveolae are flask-shaped membrane invaginations (Palade 1953, Yamada 1955, Palade & Bruns 1968, Bretscher & Whytock 1977) that have been identified in a variety of mammalian tissues including the eye (Gardiner & Archer 1986a,b, Feng et al. 1999). Though caveolae have been identified in the choroidal (Gardiner & Archer 1986a) and retinal microcirculation (Gardiner & Archer 1986a,b, Feng et al. 1999), there have been no reports of caveolae in any cellular layers of the retina, including the RPE. Interestingly, while the caveolin-1 protein was present in intact and cultured RPE, extensive inspection of the RPE cell layer revealed no evidence of the caveolar structure in either intact or cultured cells. The formation of the caveolar structure requires a number of cell type-specific factors (Vogel et al. 1998). This requirement contributes to the dynamic character of the caveola; the lack of one or more of these factors may result in the absence of the caveolar structure (Vogel et al. 1998). Caveolin-1, therefore, is often present when the caveolar structure is not (Scheiffele et al. 1998, Vogel et al. 1998). Alternatively, the RPE may not utilize caveolae for the uptake of nutrients. Caveolin-1 has been implicated in signalling cascades (reviewed by Schlegel et al. 1998). In the RPE, caveolin-1 may play an important role in signalling and may not be involved in the formation of the caveolar structure. If this is true, it would suggest that folate internalization in RPE is not dependent upon the colocalization of caveolae and folate receptor α.

In summary, the present studies show that caveolin-1 is expressed in intact and cultured RPE. Caveolin-1 is present on the basal and apical surfaces of intact RPE. In cultured cells, caveolin-1 is localized to the basolateral surface. Folate receptor α is found exclusively on the basal plasma membrane of intact and cultured RPE cells. When these studies were undertaken, the distribution of caveolin-1 was assessed in the RPE in anticipation that caveolae would be present also and might lend insight into the mechanism by which folate is internalized via folate receptors. Our studies have established for the first time the presence of caveolin-1 in the RPE and have localized it to the same membrane surface as folate receptor α. As no caveolae were detected in RPE, either in intact tissue or cultured cells, we can only surmise that folate is internalized via a non-caveolar pathway.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Manohar Ratnam of the Medical College of Ohio, Toledo, for the gift of the antibody against folate receptor α. We would also like to thank Mozaffarul Islam and Habeeb R. Ansari for their assistance with the Western blot analyses. This research was supported by: EY12830, EY13089, and HD 33347, the Medical College of Georgia Research Institute, Fight for Sight GA99037, and by an unrestricted grant from Research to Prevent Blindness, Inc. New York, to the Department of Ophthalmology, Medical College of Georgia.

References

- Anderson RG, Kamen BA, Rothberg KG, Lacey SW. Potocytosis: sequestration and transport of small molecules by caveolae. Science. 1992;255:410–411. doi: 10.1126/science.1310359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson RGW. Caveolae: Where incoming and outgoing messengers meet. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:10909–10913. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.23.10909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bretscher MS, Whytock S. Membrane-associated vesicles in fibroblasts. J Ultrastruct Res. 1977;61:215–217. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5320(77)80088-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chancy CD, Kekuda R, Huang W, Prasad PD, Kuhnel J-M, Sirotnak FM, Roon P, Ganapathy V, Smith SB. Expression and differential polarization of the reduced-folate transporter-1 and the folate receptor α in mammalian retinal pigment epithelium. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:20676–20684. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M002328200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn KC, Aotaki-Keen E, Putkey FR, Hjelmeland LM. ARPE-19, a human retinal pigment epithelial cell line with differentiated properties. Exp Eye Res. 1996;62:155–169. doi: 10.1006/exer.1996.0020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn KC, Marmorstein AD, Bonilha VL, Rodriquez-Boulan E, Giordano F, Hjelmeland LM. Use of ARPE-19 cell line as a model of RPE polarity; basolateral secretion of FGF5. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1998;39:2744–2749. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng Y, Venema VJ, Venema RC, Tsai N, Behzadian MA, Caldwell RB. VEG-F-induced permeability increase is mediated by caveolae. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1999;40:157–167. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finnemann SC, Marmorstein AD, Neill JM, Rodriquez-Boulan E. Identification of the retinal pigment epithelium protein RET-PE2 as CE-9/OX-47, a member of the immunoglobin superfamily. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1997;38:2366–2374. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardiner TA, Archer DB. Does unidirectional vesicular transport occur in retinal vessels? Brit J Ophthalmol. 1986a;70:249–254. doi: 10.1136/bjo.70.4.249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardiner TA, Archer DB. Endocytosis in the retinal and choroidal microcirculation. Brit J Ophthalmol. 1986b;70:361–372. doi: 10.1136/bjo.70.5.361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gundersen D, Orlowski J, Rodriquez-Boulan E. Apical polarity of Na,K-ATPase in retinal pigment epithelium is linked to a reversal of the ankyrin-fodrin submembrane cytoskeleton. J Cell Biol. 1991;112:863–872. doi: 10.1083/jcb.112.5.863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heth CA, Yankauckas MA, Adamian M, Edwards RB. Characterization of retinal pigment epithelial cells cultured on microporous filters. Curr Eye Res. 1987;6:1007–1019. doi: 10.3109/02713688709034872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang W, Prasad PD, Kekuda R, Leibach FH, Ganapathy V. Characterization of the N5-methyltetrahydrofolate uptake in cultured human retinal pigment epithelial cells. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1997;38:1578–1587. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Islam M, Akhtar RA. Epidermal growth factor stimulates phospholipase cgamma1 in cultured rabbit corneal epithelial cells. Exp Eye Res. 2000;70:261–269. doi: 10.1006/exer.1999.0783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleinman HK, Cannon FB, Laurie GW, Hassell, Aumailley M, Terronova VP, Martin GR, Dubois-Dalcq M. Biological activities of laminin. J Cell Biochem. 1985;27:317–325. doi: 10.1002/jcb.240270402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kono T, Sorgente N, Patterson R, Ryan SJ. Fibronectin and laminin distribution in bovine eyes. Jpn J Ophthalmol. 1983;27:496–505. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacey SW, Sanders SM, Rothberg KG, Anderson RGW, Kamen BA. Complementary DNA for the folate binding protein correctly predicts anchoring to the membrane by glycosyl-phosphatidylinositol. J Clin Invest. 1989;84:715–720. doi: 10.1172/JCI114220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laemmli UK. Cleavage of structural properties during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee HC, Shoda R, Krall JA, Foster JD, Selhub J, Rosenberry TL. Folate binding protein from kidney brush border membranes contains components characteristic of a glycoinositol phospholipid anchor. Biochemistry. 1992;31:3236–3243. doi: 10.1021/bi00127a027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowry OH, Rosebrough NJ, Farr AL, Randal RJ. Protein measurements with Folin phenol reagent. J Biol Chem. 1951;193:265–275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayor S, Rothberg KG, Maxfield FR. Sequestration of GPI-anchored proteins in caveolae triggered by cross-linking. Science. 1994;264:1948–1951. doi: 10.1126/science.7516582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mcgarvey ML, Baron Van Evercooren A, Kleinman HK, Dubois-Dalcq M. Synthesis and effects of basement membrane components in cultured rat schwann cells. Develop Biol. 1984;105:18–28. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(84)90257-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller SS, Steinberg RH, Oakley B., Jr. The electrogenic sodium pump of the frog retinal pigment epithelium. J Membr Biol. 1978;44:259–279. doi: 10.1007/BF01944224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montesano R, Roth J, Robert A, Orci L. Non-coated membrane invaginations are involved in binding and internalization of cholera and tetanus toxin. Nature. 1982;296:651–653. doi: 10.1038/296651a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okami T, Yamamoto A, Omori K, Takada T, Uyama M, Tashiro Y. Immunocytochemical localization of Na+K+-ATPase in rat retinal pigment epithelial cells. J Histochem Cytochem. 1990;38:1267–1275. doi: 10.1177/38.9.2167328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostwald TJ, Steinberg RH. Localization of frog retinal pigment epithelium Na+-K+ ATPase. Exp Eye Res. 1980;31:351–360. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4835(80)80043-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palade GE. Fine structure of blood capillaries. J Appl Phys. 1953;24:1424. [Google Scholar]

- Palade GE, Bruns RR. Structural modulations of plasmalemmal vesicles. J Cell Biol. 1968;37:633–649. doi: 10.1083/jcb.37.3.633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters KR, Carley WW, Palade GE. Endothelial plasmalemmal vesicles have a characteristic striped bipolar surface structure. J Cell Biol. 1985;101:2233–2238. doi: 10.1083/jcb.101.6.2233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinn RH, Miller SS. Ion transport mechanisms in native human retinal pigment epithelium. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1992;33:3513–3527. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ratnam M, Marquardt H, Duhring JL, Freisheim JH. Homologous membrane folate binding proteins in human placenta: cloning and sequence of a cDNA. Biochemistry. 1989;28:8249–8254. doi: 10.1021/bi00446a042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ratnam M, Freisheim JH. Proteins involved in the transport of folates and antifolates by normal and neoplastic cells. In: Picriano MF, editor. Folate Metabolism in Health and Disease. Wiley-Liss; New York: 1992. pp. 91–120. [Google Scholar]

- Rothberg KG, Ying Y, Kolhouse JF, Kamen BA, Anderson RGW. The glycophospholipid-linked folate receptor internalizes folate without entering the clathrin-coated pit endocytic pathway. J Cell Biol. 1990;110:637–649. doi: 10.1083/jcb.110.3.637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothberg KG, Heuser JE, Donzell WC, Ying Y, Glenney JR, Anderson RGW. Caveolin, a protein component of caveolae membrane coats. Cell. 1992;68:673–682. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90143-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheiffele P, Verkade P, Fra AM, Virta H, Simons K, Ikonen E. Caveolin-1 and -2 in the exocytic pathway of MDCK cells. J Cell Biol. 1998;140:795–806. doi: 10.1083/jcb.140.4.795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlegel A, Volonte D, Engelman JA, Galbiati F, Mehta P, Zhang X-L, Scherer PE, Lisanti MP. Crowded little caves: structure and function of caveolae. Cell Signal. 1998;10:456–463. doi: 10.1016/s0898-6568(98)00007-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sirotnak FM, Tolner B. Carrier-mediated membrane transport of folates in mammalian cells. Ann Rev Nutr. 1999;19:91–122. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nutr.19.1.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smart EJ, Foster DC, Ying YS, Kamen BA. Protein kinase C activators inhibit receptor-mediated potocytosis by preventing internalization of caveolae. J Cell Biol. 1994;124:307–313. doi: 10.1083/jcb.124.3.307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith SB, Kekuda R, Gu X, Chancy C, Conway SJ, Ganapathy V. Expression of folate receptor a in the mammalian retinal pigment epithelium and retina. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1999a;40:840–848. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith SB, Huang W, Chancy C, Ganapathy V. Regulation of the reduced-folate transporter by nitric oxide in cultured human retinal pigment epithelial cells. Biochem Biophys Res Comm. 1999b;257:279–283. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1999.0452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Somlyo AP, Devine CE, Somlyo AB, North SR. Sarcoplasmic reticulum and the temperature-dependent contraction of smooth muscle in calcium-free solutions. J Cell Biol. 1971;51:722–741. doi: 10.1083/jcb.51.3.722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sramek S, Wallow IHS, Bindley C, Sterken G. Fibronectin in the rat eye. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci Suppl. 1985;26:330. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugrue SP, Hay ED. Response of basal epithelial cell surfaces and cytoskeleton to solubilized extracellular matrix molecules. J Cell Biol. 1981;91:45–54. doi: 10.1083/jcb.91.1.45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun X-L, Antony AC. Identification of an 18-base cis-element in the 5′ -untranslated region of human folate receptor-α mRNA which specifically binds 46-kDa cystosolic (trans-factor) proteins. J Invest Med. 1996;44:203A. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timpl R, Rhode H, Robey PG, Rennard SI, Foidart J-M, Martin GR. Laminin – a glycoprotein from basement membranes. J Biol Chem. 1979;254:9933–9937. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turksen K, Aubin JE, Sodek J, Kalnins VI. Localization of laminin, type IV collagen, fibronectin, and heparan sulfate proteoglycan in chick retinal pigment epithelium basement membrane during embryonic development. J Histochem Cytochem. 1985;33:665–671. doi: 10.1177/33.7.3159787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verma RS, Gullapalli S, Antony AC. Evidence that the hydrophobicity of isolated, in situ, and de novo-synthesized native human placental folate receptors is a function of glycosyl-phosphatidylinositol anchoring to membranes. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:4119–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vladovsky I, Gospodarowicz D. Respective roles of laminin and fibronectin in adhesion of human carcinoma and sarcoma cells. Nature. 1981;289:304–306. doi: 10.1038/289304a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogel U, Sandvig K, Van Deurs B. Expression of caveolin-1 and polarized formation of invaginated caveolae in Caco-2 and MDCK II cells. J Cell Sci. 1998;111:825–832. doi: 10.1242/jcs.111.6.825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu M, Fan J, Gunning W, Ratnam M. Clustering of GPI-anchored folate receptor independent of both cross-linking and association with caveolae. J Memb Biol. 1997;159:137–147. doi: 10.1007/s002329900277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada E. The fine structure of the gall bladder epithelium of the mouse. J Biophys Biochem Cytol. 1955;1:455–458. doi: 10.1083/jcb.1.5.445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]