Abstract

Objectives

In VOICE, a phase IIB trial of daily oral and vaginal tenofovir for HIV prevention, ≥50% of women receiving active products had undetectable tenofovir in all plasma samples tested. MTN-003D, an ancillary study using in-depth interviews (IDIs) and focus group discussions (FGDs), together with retrospective disclosure of plasma tenofovir pharmacokinetic (PK) results, explored adherence challenges during VOICE.

Methods

We systematically recruited participants with PK data (median 6 plasma samples), categorized as low (0%, N=79), inconsistent (1%-74%, N=28), or high (≥75%; N=20) based on frequency of tenofovir detection. Following disclosure of PK results, reactions were captured and adherence challenges systematically elicited; IDIs and FGDs were audio-recorded, transcribed, coded, and thematically analyzed.

Results

We interviewed 127 participants from South Africa, Uganda, and Zimbabwe. The most common reactions to PK results included surprise (41%; low PK), acceptance (39%; inconsistent PK), and happiness (65%; high PK). Based on participants’ explanations, we developed a typology of adherence patterns: noninitiation, discontinuation, misimplementation (resulting from visit-driven use, variable taking, modified dosing or regimen), and adherence. Fear of product side effects/harm was a frequent concern, fueled by stories shared among participants. Although women with high PK levels reported similar concerns, several described strategies to overcome challenges. Women at all PK levels suggested real-time drug monitoring and feedback to improve adherence and reporting.

Conclusions

Retrospective provision of PK results seemingly promoted candid discussions around nonadherence and study participation. The effect of real-time drug monitoring and feedback on adherence and accuracy of reporting should be evaluated in trials.

Keywords: microbicide, HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis, adherence, pharmacokinetic drug detection, women, VOICE-D Study

Introduction

Despite considerable progress in HIV prevention, young women in sub-Saharan Africa experience the highest HIV incidence rates globally. Suitable prevention approaches for this vulnerable population are critically needed [1]. Oral tenofovir (TFV)-based pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) is now approved as a highly effective HIV prevention strategy when used consistently and proof of concept for investigational antiretroviral-based microbicides was demonstrated with pericoital dosing of TFV vaginal gel in the CAPRISA [Centre for the AIDS Programme of Research in South Africa] 004 trial [2]. However, because of low product adherence, the FACTS-001 [Follow-on African Consortium for Tenofovir Studies] confirmatory trial was unable to demonstrate effectiveness [3]. Indeed, suboptimal adherence explains divergent results across oral and vaginal PrEP trials, and adherence to product regimen—particularly in women—is critical for PrEP effectiveness [3-13].

The VOICE [Vaginal and Oral Interventions to Control the Epidemic] Study investigated the effectiveness of daily oral tenofovir, oral tenofovir-emtricitabine (TDF-FTC), and 1% vaginal TFV gel for preventing male-to-female sexual transmission of HIV-1 in Africa. Based on self-reports and returned products at the clinics, product adherence was high (>90%). However, ≥50% of women assigned to active products in a representative subcohort had undetectable TFV in all plasma samples tested, likely explaining the lack of protection observed in the intent-to-treat analyses [12]. Specifically, ≤30% of plasma samples had detectable TFV levels among women assigned to active tablets; 25% of plasma samples and 49% of cervicovaginal fluid (CVF) samples had detectable TFV levels among those assigned to active gel [12].

In addition to achieving adherence to study products, accurately measuring adherence has been a challenge in HIV prevention trials. Behavioral and electronic measures are known to overestimate product use, and biological measurements have limitations, too [14, 15]. Nevertheless, pharmacokinetic (PK) measures have provided clear evidence of an association between plasma drug concentration and recent TFV dosing, and additional techniques are in development to improve detailing patterns of product use over time [13, 16-20].

VOICE participants’ engagement and adherence, or lack thereof, have previously been examined, including the role of visit retention and of male partners [21-23]. This study took a different approach, by providing individualized plasma TFV results to former active-arm VOICE participants, to elicit greater details about their varying levels of adherence. It is among the first to provide trial participants with direct feedback on their drug levels and to explore their reactions and explanations.

Methods

VOICE trial: behavioral and pharmacological measures of adherence

The VOICE trial (MTN-003; ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT00705679) was conducted from 2009 to 2012 at 15 sites among 5029 women from Uganda, South Africa, and Zimbabwe. The trial design, population, procedures, and primary findings were previously published [12]. Behavioral adherence assessments included face-to-face interviews (FTFI), audio computer-assisted self-interviewing (ACASI), and pharmacy product counts (PC). Post-trial analysis of TFV in plasma and in CVF was conducted in samples collected at selected quarterly visits in a random subcohort of active-arm participants [12]. The lower limit of quantification (LLOQ) for TFV in plasma (0.31 ng/ml) corresponded to no tablet used in the prior 7 days or no gel used in the prior 2-3 days [16, 17].

VOICE-D study design and setting

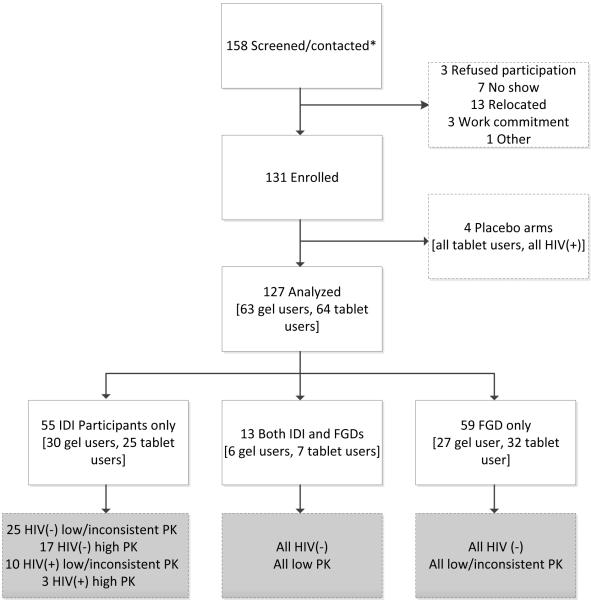

VOICE-D (MTN-003D) was a two-stage multisite qualitative ancillary study conducted in Kampala, Uganda; Durban, South Africa; and Chitungwiza, Zimbabwe [24]. This article includes data collected from November 2013 through March 2014 during the second stage of the study, when participants were retrospectively presented with their PK results. The findings related to sexual behaviour captured during the first stage have been published elsewhere [25-27]. Former VOICE participants were recruited from among those who had provided permission to be recontacted and had plasma TFV data. Recruitment was stratified by VOICE HIV-seroconversion status, tablet or gel assignment, and one of three PK detection levels: low (no plasma TFV detected at any visit), inconsistent (plasma TFV detected at 1%-74% of visits), and high (plasma TFV detected at 75%-100% of visits). Participants in each recruitment group were randomly selected and contacted in ascending order from a list generated by the Data Coordinating Center until target numbers were reached (Figure 1).

Figure 1. VOICE-D participants study flow.

VOICE-D enrolment target was 144 participants, and at each site,we aimed to conduct two to four in-depth interviews (IDIs) with women from each recruitment group: seronegative (HIV-negative) and seropositive (HIV-positive) low or inconsistent PK gel, high PK gel, low or inconsistent PK tablet, high PK tablet and four gel or tablet-specific focus group discussions (FGDs) with HIV-seronegative participants with low or inconsistent PK levels. A total of 127 women who were all on active products during VOICE were interviewed and analysed. This represents 88% of the original target of 144 former VOICE participants. 68 IDIs and 12 FGDs were conducted, 6 FGDs with gel users and 6 FGDs with tablet users, with a range of 4–10 participants in each FGD. Seronegative: HIV(−) and seropositive: HIV(+); pharmacokinetic (PK). * Does not include those attempted to contact, but unable to reach.

Procedures

Following written informed consent, participants completed a short demographic questionnaire. Trained female research staff who had not interacted with participants during VOICE, privately presented participants with their plasma PK results using a pretested pictorial tool (Supplemental Digital Content 1) [28]. Participants were informed of the category (0, 1%-49%, 50%-74%, 75%-99%, and 100%) corresponding to the frequency of TFV plasma detection from quarterly samples tested in VOICE, and were told that TFV detection only indicated recent product use. Because of the novelty of presenting PK results and our uncertainty regarding how participants would react, staff assessed and recorded participants’ immediate response on a Case Report Form (CRF) according to a list of basic emotions [29], with an option for other responses. In-depth interviews (IDIs) and Focus Group Discussions (FGDs) were conducted at a location intended to be neutral and unaffiliated with the VOICE clinic site. Interviews followed a standardized guide, were conducted in the participants’ language of choice, audio-recorded, transcribed, and translated into English. The guides focused on product experiences and adherence challenges and included a card pile sort and ranking exercise with IDI participants [28, 30] (Supplemental Digital Content 2). Staff received in-person training from the investigators on how to present PK results in a nonjudgmental manner.

Data analysis

Transcripts were coded in NVivo 10 by the multisite analysis team; high (≥80%) inter-coder reliability was maintained and calculated as previously described [21]. Coded data were concatenated into reports by thematic area, then summarized into memos [30]. Memos were further analysed to reveal patterns related to PK results and adherence, contrasting findings from participants displaying low/inconsistent and high PK levels as well as those in tablet and gel groups.

VOICE-D participants were compared to VOICE participants not enrolled in VOICE-D at the same sites using Fisher’s exact test for the following baseline characteristics: age, marital status, education, income, parity, sexual partners, and sexual behavior. The rank-order for which each adherence challenge card was selected was assigned a weighted score, averaged, and presented in descending order of relevance [28].

The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Boards at RTI International and at each of the study sites, and was overseen by the regulatory infrastructure of the U.S. National Institutes of Health and the Microbicide Trials Network.

Results

The study sample (N=127) included 49 participants from Uganda, 48 from Zimbabwe, and 30 from South Africa, with similar numbers of women in the active tablet and gel groups. PK groups included 79 classified as low (62%), 28 as inconsistent (22%), and 20 as high (16%), based on an average of 6.7 VOICE visits among the 114 HIV-negative participants and 4.2 visits among the 13 HIV-positive participants (Table 1). IDIs were conducted with 68 women (13 women also joined an FGD) and the remainder participated only in an FGD (Figure 1). VOICE-D participants were younger and less well educated than other VOICE participants at the same sites (Supplemental Digital Content 3).

Table 1.

Characteristics of VOICE-D Participants

| At time of VOICE-D interview | N=127 | Percent | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Country (site) | South Africa (Durban) | 30 | 24% |

| Uganda (Kampala) | 49 | 39% | |

| Zimbabwe (Chitungwiza) | 48 | 38% | |

| Age: median (mean, range) | 28 (29.3, 21-41) | ||

| Currently married | 72 | 57% | |

| Has current primary sex partner or is married | 118 | 93% | |

| Lifetime partners: median (mean, range1) | 3 (11.8, 1-99+) | ||

| Completed secondary school or more | 47 | 37% | |

| Earns her own income | 94 | 74% | |

| Religion | Christian | 108 | 85% |

| Muslim | 14 | 11% | |

| Other/None | 5 | 4% | |

|

| |||

| During VOICE trial | |||

|

| |||

| VOICE study product group | |||

| Gel | 63 | 50% | |

| Tablets | 64 | 50% | |

| Median number of visits with PK data (mean, range) | 6 (6.4; 1-11) | ||

| Among HIV negatives (N=114) | 6 (6.7; 3-11) | ||

| Among seroconverters/HIV positives (N=13) | 4 (4.2; 1-9) | ||

| Median month of follow-up in VOICE (mean, range) | 17 (17.5; 7-27) | ||

| Pharmacokinetic (PK) group | |||

| Low | 79 | 62% | |

| Inconsistent | 28 | 22% | |

| High | 20 | 16% | |

Participants with 99 or more sex partners were checked as "99." All those who reported 99+ partners came from Uganda.

Product adherence during VOICE

Table 2 presents plasma TFV detection rates at the first quarterly visit, last visit with PK testing, and average across VOICE visits in women assigned to each of the PK groups. Women with low PK had no detectable TFV at any visit; for those classified with high PK, 85% had TFV detectable at first quarterly visit, and an average of 90% across visits. Among those with inconsistent PK, the average was 31% across visits; TFV detection was 46% at first visit and 18% at last visit, with evidence of decreased detection over time (McNemar test; p=0.04). Assessments based on self-reports and product counts during VOICE suggested ≥90% product adherence among VOICE-D participants of all PK levels, as previously described for the entire VOICE sample [12].

Table 2.

Participants' Adherence Level in VOICE and Reaction to PK results, by Plasma PK Level and Overall

| Plasma PK level |

Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low n=79 (%) |

Inconsistent n=28 (%) |

High n=20 (%) |

n=127 (%) | |

| VOICE biological measures of adherence (drug detection) | ||||

|

| ||||

| VOICE plasma tenofovir (TFV) PK data | ||||

| TFV detected at first quarterly visit(*) | 0 | 13(46%) | 17(85%) | 30(24%) |

| TFV detected at last visit with PK testing(**) | 0 | 5(18%) | 15(79%) | 20(16%) |

| Median % visits with TFV detected (mean, range)1 | 0(0, 0-0) | 25(30.8, 11-71) | 95(89.9, 75-100) | 0(21, 0-100) |

|

| ||||

| TFV detected in cervicovaginal fluid at Month 6 in gel subset [N=42] (***) | 10(42%) | 8(62%) | 5(100%) | - |

|

| ||||

| VOICE behavioral measures of adherence (matching for visits where plasma PK results were available) | ||||

|

| ||||

| ACASI: average adherence(%) across visits,2 median (mean, min-max) | 100(94, 0-100) | 100(89, 25-100) | 100(98, 81-100) | 100(93, 0-100) |

| FTFI: Average adherence (%) across visits,2 median (mean, min-max) | 100(95, 33-100) | 100(91, 25-100) | 100(100, 93-100) | 100(95, 25-100) |

| PC: Cumulative adherence (%),3 median (mean, min-max) | 99(93, 40-114) | 99(93, 58-102) | 99(92, 35-103) | 99(93, 35-114) |

|

| ||||

| VOICE-D: Reactions to PK results upon category disclosure (multiple answers allowed) | ||||

|

| ||||

| Surprise | 32(41%) | 7(25%) | 4(20%) | 43(34%) |

| Disbelief | 29(37%) | 7(25%) | - | 36(28%) |

| Neutral | 15(19%) | 4(14%) | 4(20%) | 23(18%) |

| Acceptance | 8(10%) | 11(39%) | 2(10%) | 21(17%) |

| Happiness | - | - | 13(65%) | 13(10%) |

| Distress/Unhappiness | 7(9%) | 1(4%) | 1(5%) | 9(7%) |

| Sadness | 7(9%) | 1(4%) | - | 8(6%) |

| Other4 | 7(9%) | 1(4%) | - | 8(6%) |

ACASI, audio-computer assisted self-interviewing; FTFI, face-to-face interview; PC, pharmacy product count (monthly returns of unused products at the clinic).

117 (92%) has their first visit with PK results at Month 3, for the remaining 10, it was at Months 4 to 6;

mean monthly visit for last PK result was Month 17 (low PK) and Month 16 (inconsistent and high PK).

Subset in gel group with swab test.

Excluding post-seroconversion visits for seropositives;

Assessed product use in past 7 days, denominator is women;

Cumulative adherence across visits, denominator is women;

Other: anger (N=2), embarrassed/uncomfortable (N=3), confused (N=1), laughed (N=1) in low group, fear (N=1) in inconsistent group.

Disclosure of PK results

Provision of plasma PK results generated a variety of reactions, including surprise (41%) and disbelief (37%) among women with low PK and acceptance (39%) among women with inconsistent PK. Women with high PK expressed happiness (65%) and most agreed with their results (Table 2). During the IDIs, a majority of women with low/inconsistent PK also came to accept their results (63%); participants in the FGDs reacted similarly. When objecting, many provided detailed explanations of why they felt their results were erroneous (e.g., intentionally dosing prior to study visits, or using products some of the time). A few attributed nondetection to problems with the PK testing (i.e., inaccuracy, interference with other medications, or alcohol consumption) or being randomized to placebo as an explanation (Supplemental Digital Content 4).

Typology of product use

Participants described a variety of reasons and circumstances that influenced nonadherence. A typology was developed that depicted four main adherence patterns: (1) noninitiation, whereby participants never engaged with the product regimen; (2) discontinuation, whereby participants stopped temporarily or permanently following product initiation; (3) misimplementation whereby participants persisted but exhibited various behaviors resulting in incorrect use; and (4) adherence defined as using product daily as instructed during the trial (Supplemental Digital Content 5). Discontinuation and misimplementation may or may not be intentional. Furthermore, misimplementation included four subpatterns based on participants’ explanations: visit-driven use, or white-coat compliance, described dosing prompted by an upcoming visit to the clinic; variable-taking referred to skipping doses when the set time for taking products was missed; modified dosing occurred when participants took extra or partial doses (e.g., emptying only part of a gel applicator) or engaged in other behaviors that impacted administration of a full dose (e.g., vaginal wiping or cleansing); a modified regimen described variability in frequency of intake, such as missing product use for single or sequential days (e.g., skipping, episodic use; product holiday), which was sometimes described as intentional, and more often as unintentional, such as forgetting or being unable to use on a given day or for a given period. Table 3 provides additional descriptions of each typology with supporting quotations. Based on their explanations, women often displayed several subpattern types concurrently or consecutively, highlighting the dynamic and complex nature of adherence-related behaviors (see case studies, Table 4).

Table 3.

Typology of Women’s Reported Product Use Patterns: Descriptions and Illustrative Quotes

| Noninitiation | This pattern was uncommon and stemmed from a stated lack of interest in the products. Very few acknowledged disinterest from the start. Some described these participants as “greedy” for not using products and coming to the visits solely for the reimbursements.

|

| Discontinuation | This common pattern represents women who reported initiating product use but then stopped temporarily or permanently. Circulating stories generated fear or mistrust of the research and led to discontinuation. Other negative influences were unsupportive partners, family members, or community rumors. Waning motivation, driven by a burdensome daily regimen, unpleasant experience using products (e.g., leaky gel, tablets too big), side effects, unknown efficacy, and believing oneself to be on placebo also resulted in discontinuation. Some restarted using product toward the end of the trial because they realized they “worked,” that they should not believe rumors, or when they felt an immediate risk from a promiscuous sexual partner.

|

| Misimplementation | This pattern describes women who remained persistent with the regimen, but used their products incorrectly or inconsistently. Misimplementation stemmed from various behaviors described by these subpatterns: Visit-driven use: Product use prior to coming to the study visits was mentioned occasionally – across all PK levels – either because the visit acted as a reminder, or because women wanted to ensure products would be detectable in their blood. Indeed, a majority – but not all – of the women understood that their blood was tested for presence of the study drug during VOICE, but they were not given the test results since testing occurred after study’s end.

|

| Adherence | This pattern was commonly described among women with high PK level, but also among those with low/ inconsistent PK levels who denied their results. These women described strong internal motivations, because they were committed or felt an obligation toward the study, they wanted to contribute to the study’s results, they trusted the researchers and products, wanted to protect themselves, or for altruism. Some assigned to gel also mentioned gel lubricating properties, and improved sexual experiences as beneficial.

|

Table 4.

Case Studies

| Case 1. Ugandan gel participant, low PK level, 34 years old, married, financially dependent on husband |

|

| Case 2. South African tablet participant, low PK level, 26 years old, unmarried, one sexual partner in past 3 months |

|

| Case 3. Zimbabwean tablet participant, low PK level, 24 years old, married, lives separately from partner |

|

Legend: The three case studies were selected to demonstrate the complexity and interplay of issues described by VOICE participants as impacting their adherence. These particular cases were selected to represent participants from each country in the low PK group, with representation of those assigned to gel and to tablets. They were also emblematic of the common themes identified throughout VOICE-D in terms of motivation to join and stay in the trial and reported challenges associated with product use, while displaying a diversity of incorrect product implementation patterns (modified dosing; modified regimen, visit-driven use, discontinuation).

Adherence challenges, motivation to be in the study, and strategies for study participation

Among the 20 statement cards related to study participation and adherence challenges, IDI participants ranked the following statements as most salient: “I experienced or was worried about side effects”; “The products may be harmful”; and “I joined the study for health services provided by the clinic” (see Supplemental Digital Content 3). These rankings were similar for women in tablet or gel groups, and for those with low/inconsistent and high PK. The adherence issues raised in the card pile ranking activity were consistent with challenges commonly discussed in the FGDs. As noted by one participant, fear of side effects and/or harm from the product was fueled by waiting room stories:

A lot of women stopped taking their tablets because they listened to others. People who experienced side effects might not have been that many, but some of us just copied what others were saying, when you heard someone say “The tablets are dangerous” [or] “They make me feel weak” [or] they do this and that, you would also stop using them too.

(FGD, Zimbabwe, low/inconsistent PK, tablet)

Women with high PK reported similar challenges; however, several indicated how they overcame negative comments from other participants, partners, or family members by ignoring them, avoiding situations where their trial participation would be questioned or exposed to criticism (i.e., avoiding interactions with others, using product discreetly), maintaining their internal motivation as “it really comes from your heart” (IDI, Uganda, high PK, tablet), reminding themselves of the care provided at the clinic, and trusting and feeling encouraged by the staff:

“While at home, the words of the counsellors would resound in your ears. If you did not forget, it made it a lot easier.”

(IDI, Uganda, high PK, tablet).

All participants emphasized that access to quality health services, free treatments, and regular HIV testing were motivations to join and remain in the trial, even when not taking study products. The education they gained, as well as curiosity about trial results also kept women involved. Reimbursement was appreciated but typically not reported to be a main reason for staying in VOICE. Participants also mentioned remaining in the trial after discontinuing product use, because they felt obligated from having signed a “contract” (the informed consent), they felt trapped and pursued if they decided to stop, or feared being alleged as seroconverters if they terminated early. Several women worried about being discontinued from the study if they reported or were found to be nonadherent. Others stated not wanting to “fail” or feared being reprimanded by staff if they reported adherence challenges. Conversely, some women said that it was easier to appear adherent as no one could detect their nonuse. Thus, women chose to maintain an appearance of high adherence. To return the correct number of unused products to the clinic, women described counting, decanting, stock-piling, burning, burying, dumping, or throwing extra products in toilets or trash cans or sharing surplus with others.

To encourage honest response and product use, participants at all sites and across PK levels recommended real-time product use monitoring and feedback in future trials:

“I think if the results of the blood tests came out immediately, then it can also be immediately established whether you were using the product or not. Then, they should tell you, your blood test results. This approach will make you feel more compelled to use the products properly.”

(IDI, Zimbabwe, low PK, gel)

Other strategies mentioned to improve motivation and adherence outcomes in future trials included the study providers administering the product rather than participants, not requiring daily use, fewer opportunities for waiting room conversations among participants, rewards for high adherence, more fun and social activities, and improved staff-participant interactions.

Discussion

VOICE-D was a qualitative study among 127 participants from Uganda, South Africa, and Zimbabwe that aimed to provide insight into women’s motivations, experiences, and behaviors regarding product use during the VOICE trial through retrospective provision of plasma PK results collected during the trial. Three important findings emerged from this study. First, presenting women with their PK results was acceptable, understood, and elicited open discourse on product nonuse. Second, individual patterns of product nonuse and the reasons behind them, were complex and underscored the need for multipronged and tailored approaches to adherence support. Third, participants suggested that real-time product adherence monitoring and feedback be used in future trials.

During the design and ethical review of this study, discussion focused on how to present women with their PK results in a clear and neutral manner, how women might feel and respond when presented with objective information about product nonuse [31]. Although women’s reactions to receiving PK results varied, few were negative, and the majority who initially disagreed with or denied their results ultimately accepted them, implying that provision of adherence results was acceptable and understood. Importantly, participants—the majority of whom had low or inconsistent plasma TFV detected during VOICE—openly discussed their product experiences, suggesting that feedback using objective measures may effectively bridge an important gap in reporting, which historically has posed a challenge in prevention trials. In VOICE-C, a qualitative study conducted concurrently with VOICE, women were unwilling to personally acknowledge nonadherence [21]. In VOICE-D, only after provision of PK results did women acknowledge nonuse as well as other socially undesirable behaviors [32].

Women’s complex accounts of product nonuse during VOICE suggested a variety of circumstances and patterns that informed a typology—based on participants’ descriptions and existing adherence literature definitions [33, 34]—that is useful insofar as it demarcates different patterns of use, informs interpretation of overall trial and drug PK results, clarifies challenges that inhibit correct and sustained product use, and identifies points of entry for tailored approaches to support adherence. Women often reported intertwined patterns, underscoring the situational, social, and temporal complexities affecting product adherence. Indeed, a variety of factors operating at different socioecological levels influenced participants’ product use [21, 35]. Although several physical attributes of the gel and tablets and the daily regimen were discussed as hurdles for sustained use, many adherence challenges and reported patterns were not directly related to the type of product. This suggests that low use in the context of this effectiveness trial was less affected by the products themselves than by contextual influences, including fear of side effects/harm propagated through waiting room stories and concerns about receiving an investigational drug. These negative influences were experienced in the gel and tablet groups and across PK levels, although those with high PK indicated strategies to overcome these challenges. The typology also suggests that developing combination adherence support interventions that address multiple needs and levels of influence might be more effective. Adherence support for HIV prevention methods will likely evolve as effective products progress from research trials to demonstration projects and into real-world settings. Notably, in a recent oral PrEP demonstration project, high adherence to daily use of Truvada™—whose efficacy is now established—was achieved among young South African women, with robust adherence monitoring and support [36].

Participants recommended real-time monitoring and feedback as a way to motivate product use and encourage greater honesty in self-reports. A tailored adherence support intervention based on unannounced pill counts achieved near perfect adherence among HIV-serodiscordant couples in Uganda [37]. Notwithstanding the cost and logistical challenges of providing near or real-time monitoring, recommendations from VOICE-D participants have been incorporated into the next generation of MTN trials to the extent that study designs permit, including provision of aggregated site-level drug results in placebo-controlled trials and individual drug results in open label studies [38, 39]. Moreover, to accommodate a range of study designs, as well as real-world implementation, more creative approaches are needed to objectively monitor and provide feedback to participants in a straightforward yet culturally sensitive and cost-effective manner.

This study has several limitations. First, the sample was selected based on predetermined criteria; consequently, the adherence information derived may be different from that of women who did not join VOICE-D, and may not represent challenges faced by all women in the surrounding communities. The VOICE-D sample was demographically and behaviorally similar to the VOICE sample at the same sites, except for being younger and less educated. Second, plasma TFV testing cannot determine patterns of product use and fluctuating behavior as described by VOICE-D participants; given the narrow window of detection it cannot distinguish either between visit-driven use and adherence. Other trials have used different biological measures to assess use over longer periods and circumvent white-coat compliance [5, 11, 16]. Although women with high PK described fewer adherence challenges compared with women with low PK [40] and described strategies to overcome challenges, we cannot rule out that women with high PK were exhibiting white-coat compliance, a behavior also observed in HIV treatment trials [41]. Hence, the focus of this study was on women with low and inconsistent PK who had documented nonadherence. Finally, although participants were forthcoming about nonuse and discussed a range of socially undesirable behaviors (e.g., vaginal practices, techniques for counting and discarding products, white-coat compliance), social desirability bias may have been present and women may have underreported nonuse. Of note, in the subset of gel group participants whose CVF was tested at Month 6 (first vaginal swab collection time), a higher proportion of women had TFV detectable in CVF than in plasma, as might be anticipated based on the longer TFV detection window in CVF. Hence, the CVF data support the descriptions from the interviews, suggesting that varied incorrect or inconsistent patterns were more dominant compared to noninitiation or early discontinuation.

This study successfully elicited more honest reporting of adherence challenges and product nonuse during VOICE by providing women with their drug-level data and interviewing in a neutral and nonjudgmental manner. Improved relationships between staff and participants to support use and address ongoing challenges, without fearing negative consequences for honestly reporting nonadherence could contribute to more effective support interventions in future studies, although implementation is not necessarily straightforward [42-44]. Given the role of peer interactions and social influences on adherence, interventions could be designed to promote a positive social discourse around product use and supportive norms fostering commitment toward the study and its objectives. Initiatives to promote participants’ engagement are being implemented in the next generation of prevention trials [45]. Finally, real-time product use monitoring and feedback to participants should be further evaluated in future trials for improving accuracy of self-reports and motivating high product adherence.

Supplementary Material

Ariane van der Straten is the protocol chair and led the writing of this manuscript. Elizabeth Montgomery and Barbara Mensch are protocol co-chairs and co-led study design, implementation, analysis and writing. Miriam Hartmann, Lisa Levy, Petina Musara, Juliane Etima, Sarita Naidoo and Thola Bennie were directly involved with study implementation. Miriam Hartmann, Thola Bennie, Nicole Laborde were part of the qualitative analysis team. Helen Cheng conducted the quantitative analyses. Jeanna Piper and Cynthia Grossman are representative of the agencies co-sponsoring the study and contributed to the study design; Jeanne Marrazzo is the protocol chair of the parent trial VOICE and contributed to study design.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the women who participated in this study. The contributions of the MTN Leadership and Operations Center, the VOICE trial leadership, staff at FHI360, and RTI International, site leaders, and protocol study team members are acknowledged as critical in the development, implementation, and/or analysis of this study.

Sources of support:

This study was designed and implemented by the Microbicide Trials Network (MTN). MTN-003D was funded by the U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH). The Microbicide Trials Network is funded by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (UM1AI068633, UM1AI068615, UM1AI106707), with co-funding from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development and the National Institute of Mental Health, all components of NIH. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of NIH.

Footnotes

Meeting at which part of the data were presented:

HIV R4P conference Cape Town, October 2014

Conflicts of Interest:

All authors declare they do not have any related conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS . Global report: UNAIDS report on the global AIDS epidemic: 2013. UNAIDS; Geneva: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abdool Karim Q, Abdool Karim SS, Frohlich JA, Grobler AC, Baxter C, Mansoor LE, et al. Effectiveness and safety of tenofovir gel, an antiretroviral microbicide, for the prevention of HIV infection in women. Science. 2010;329:1168–1174. doi: 10.1126/science.1193748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rees H, Delany-Morelwe SA, Lombard C. FACTS 001 phase III trial of pericoital tenofovir 1% gel for HIV prevention in women. Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections (CROI); Seattle, WA. Feb 23-26, 2015. pp. 23–26. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baeten JM, Grant R. Use of antiretrovirals for HIV prevention: what do we know and what don’t we know? Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2013;10:1–10. doi: 10.1007/s11904-013-0157-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grant RM, Lama JR, Anderson PL, McMahan V, Liu AY, Vargas L, et al. Preexposure chemoprophylaxis for HIV prevention in men who have sex with men. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:2587–2599. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1011205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Choopanya K, Martin M, Suntharasamai P, Sangkum U, Mock PA, Leethochawalit M, et al. Antiretroviral prophylaxis for HIV infection in injecting drug users in Bangkok, Thailand (the Bangkok Tenofovir Study): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2013;381:2083–2090. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61127-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baeten JM, Donnell D, Ndase P, Mugo NR, Campbell JD, Wangisi J, et al. Antiretroviral prophylaxis for HIV prevention in heterosexual men and women. N Engl J Med. 2012:1–12. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1108524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thigpen MC, Kebaabetswe PM, Paxton LA, Smith DK, Rose CE, Segolodi TM, et al. Antiretroviral preexposure prophylaxis for heterosexual HIV transmission in Botswana. N Engl J Med. 2012:1–12. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1110711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.van der Straten A, Van Damme L, Haberer JE, Bangsberg DR. Unraveling the divergent results of pre-exposure prophylaxis trials for HIV prevention. AIDS. 2012;26:F13–19. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3283522272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baeten J, Celum C. Systemic and topical drugs for the prevention of HIV infection: antiretroviral pre-exposure prophylaxis. Annu Rev Med. 2013;64:219–232. doi: 10.1146/annurev-med-050911-163701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Van Damme L, Corneli A, Ahmed K, Agot K, Lombaard J, Kapiga S, et al. Preexposure prophylaxis for HIV infection among African women. N Engl J Med. 2012;1:12. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1202614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Marrazzo JM, Ramjee G, Richardson BA, Gomez K, Mgodi N, Nair G, et al. Tenofovir-based preexposure prophylaxis for HIV infection among African women. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:509–518. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1402269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Buchbinder S, Liu A. CROI 2015: advances in HIV testing and prevention strategies. Top Antivir Med. 2015;23:8–27. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.van der Straten A, Montgomery ET, Hartmann M, Minnis A. Methodological lessons from clinical trials and the future of microbicide research. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2013;10:89–102. doi: 10.1007/s11904-012-0141-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tolley EE, Harrison PF, Goetghebeur E, Morrow K, Pool R, Taylor D, et al. Adherence and its measurement in phase 2/3 microbicide trials. AIDS Behav. 2010;14:1124–1136. doi: 10.1007/s10461-009-9635-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hendrix CW, Chen BA, Guddera V, Hoesley C, Justman J, Nakabiito C, et al. MTN-001: randomized pharmacokinetic cross-over study comparing tenofovir vaginal gel and oral tablets in vaginal tissue and other compartments. PLoS One. 20138:e55013. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0055013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hendrix CW, Andrade A, Kashuba A, Marzinke M, Anderson PL, Moore A, et al. Tenofovir-emtricitabine directly observed dosing: 100% adherence concentrations (HPTN 066). 21st Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections; Boston, MA. Mar 3-6, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hendrix CW. Exploring concentration response in HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis to optimize clinical care and trial design. Cell. 2013;155:515–518. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.09.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Grant RM, Anderson PL, McMahan V, Liu A, Amico KR, Mehrotra M, et al. Uptake of pre-exposure prophylaxis, sexual practices, and HIV incidence in men and transgender women who have sex with men: a cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2014;14:820–829. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(14)70847-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Anderson PL, Glidden DV, Liu A, Buchbinder S, Lama JR, Guanira JV, et al. Emtricitabine-tenofovir concentrations and pre-exposure prophylaxis efficacy in men who have sex with men. Sci Transl Med. 2012;4:151ra125. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3004006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.van der Straten A, Stadler J, Montgomery E, Hartmann M, Magazi B, Mathebula F, et al. Women’s Experiences with Oral and Vaginal Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis: The VOICE-C Qualitative Study in Johannesburg, South Africa. PLoS ONE. 20149:e89118. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0089118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Magazi B, Stadler J, Delany-Moretlwe S, Montgomery E, Mathebula F, Hartmann M, et al. Influences on visit retention in clinical trials: insights from qualitative research during the VOICE trial in Johannesburg, South Africa. BMC Womens Health. 2014;14:88. doi: 10.1186/1472-6874-14-88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Montgomery ET, van der Straten A, Stadler J, Hartmann M, Magazi B, Mathebula F, et al. Male partner influence on women's HIV prevention trial participation and use of pre-exposure prophylaxis: the importance of "understanding". AIDS Behav. 2015;19:784–793. doi: 10.1007/s10461-014-0950-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.van der Straten A, Mensch B, Montgomery E. MTN-003D: an exploratory study of potential sources of efficacy dilution in the VOICE trial. DAIDS; Kampala, Uganda, Durban, South Africa and Chitungwi, Zimbabwe: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Naidoo S, Woeber K, Munaiwa O, Etima J, Duby Z, Hartmann M, et al. Application of a Body Map Tool to Enhance Discussion of Sexual Behaviour in Women: Experiences from MTN 003D. AIDS Res Hum Retrov. 2014;30:A11–A11. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Duby Z, Hartmann M, Mahaka I, Montgomery ET, Colvin CJ, Mensch B, et al. Language, terminology and understanding of anal sex amongst VOICE participants in Uganda, Zimbabwe and South Africa. AIDS Res Hum Retrov. 2014;30:A10–A11. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Duby Z, Hartmann M, Montgomery ET, Colvin CJ, Mensch B, van der Straten A. Perceptions and practice of heterosexual anal sex amongst VOICE participants in Uganda, Zimbabwe and South Africa. AIDS Res Hum Retrov. 2014;30:A269–A269. [Google Scholar]

- 28.van der Straten A, Montgomery E, Hartmann M, Levy L, Piper J, Mensch B. Strategies to explore factors impacting study product adherence among women in VOICE. IAPAC Conference; Miami, FL. Jun 8-10, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Eckman P. Basic emotions. In: Dalgleish T, Power M, editors. Handbook of cognition and emotion. John Wiley & Sons Ltd; Sussex, UK: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Guest G, MacQueen KM. Handbook for team-based qualitative research. Rowman Altamira; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Etima J, Nakabiito C, Akello CA, Kabwigu S, Nakyanzi T, Nabukeera J, et al. To give or not to give PK results: an ethical dilemma for researchers & regulators in Uganda. AIDS Res Hum Retrov. 2014;30:A42–A42. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Musara P, Munaiwa O, Mahaka I, Mgodi NM, Hartmann M, Levy L, et al. The effect of presentation of Pharmacokinetic (PK) drug results on self-reported study product adherence among VOICE participants in Zimbabwe. AIDS Res Hum Retrov. 2014;30:A42–A42. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vrijens B, Vincze G, Kristanto P, Urquhart J, Burnier M. Adherence to prescribed antihypertensive drug treatments: longitudinal study of electronically compiled dosing histories. BMJ. 2008;336:1114–1117. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39553.670231.25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Blaschke TF, Osterberg L, Vrijens B, Urquhart J. Adherence to medications: insights arising from studies on the unreliable link between prescribed and actual drug dosing histories. Annu Rev Pharmacol. 2012;52:275–301. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pharmtox-011711-113247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.van der straten A, Stadler J, Luecke E, Laborde N, Hartmann MEM. Perspectives on use of oral and vaginal antiretrovirals for AQ7 HIV prevention: the VOICE-C qualitative study in Johannesburg, South Africa. J Int AIDS Soc. 2014;17:19146. doi: 10.7448/IAS.17.3.19146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bekker L-G, Grant R, Hughes J, Roux S, Amico R, Hendrix C, et al. HPTN 067/ADAPT Cape Town: a comparison of daily and nondaily PrEP dosing in African women. Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections; Seattle, WA. Feb 23-26, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Haberer JE, Baeten JM, Campbell J, Wangisi J, Katabira E, Ronald A, et al. Adherence to antiretroviral prophylaxis for HIV prevention: a substudy cohort within a clinical trial of serodiscordant couples in East Africa. PLoS Med. 2013;10:e1001511. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Microbicide Trials Network (MTN) Researchers launch first-ever Phase II safety study of a rectal microbicide to prevent HIV. Microbicide Trials Network; Pittsburgh, PA: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Microbicide Trials Network (MTN) In: Questions and Answers: VOICE C and VOICE D social and behavioral research sub-studies of VOICE. Rossi L, editor. Microbicide Trials Network; Pittsburgh, PA: 2014. http://www.mtnstopshiv.org/news/studies/mtn003cd/qa. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mensch BS, van der Straten A, Hartmann M, Cheng H, Miller B, Piper J, et al. Reporting of challenges to adherence in VOICE: a comparison of quantitative and qualitative self-reports among women during and after the trial. AIDS Res Hum Retrov. 2014;30:A252–A252. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Podsadecki TJ, Vrijens BC, Tousset EP, Rode RA, Hanna GJ. “White Coat Compliance” limits the reliability of therapeutic drug monitoring in HIV-1—infected patients. HIV Clinical Trials. 2008;9:238–246. doi: 10.1310/hct0904-238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Corneli AL, McKenna K, Perry B, Ahmed K, Micro M, Agot K, et al. The science of being a study participant: FEM-PrEP participants’ explanations for over-reporting adherence to the study pills and for the whereabouts of unused pills. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2015;68(5):578–84. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Amico KR, Mansoor LE, Corneli A, Torjesen K, van der Straten A. Adherence support approaches in biomedical HIV prevention trials: experiences, insights and future directions from four multisite prevention trials. AIDS Behav. 2013;17:2143–2155. doi: 10.1007/s10461-013-0429-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.van der Straten A, Mayo A, Brown E, Amico KR, Cheng H, Laborde N, et al. Perceptions and experiences with the VOICE Adherence Strengthening Program (VASP) in the MTN-003 Trial. AIDS Behav. 2015;19:770–783. doi: 10.1007/s10461-014-0945-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schwartz K, Ndase P, Torjesen K, Mayo A, Scheckter R, van der Straten A, et al. Supporting participant adherence through structured engagement activities in the MTN-020 (aspire) trial. AIDS Res Hum Retrov. 2014;30:A80–A80. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.