Abstract

The potential medical applications of nanoparticles warrant their investigation in terms of biodistribution and safety during pregnancy. The transport of silica nanoparticles (NPs) across the placenta was investigated using two models of maternal-fetal transfer in human placenta, namely, the BeWo b30 choriocarcinoma cell line and the ex vivo perfused human placenta. Nanotoxicity in BeWo cells was examined by the MTT assay and demonstrated decreased cell viability at concentrations greater than 100 μg/mL. In the placental perfusion experiments, antipyrine crossed the placenta rapidly, with a fetal/maternal ratio of 0.97 ± 0.10 after 2 hours. In contrast, the percentage of silica NPs reaching the fetal perfusate after 6 hours was limited to 4.2 ± 4.9% and 4.6 ± 2.4% for 25-nm and 50-nm NPs, respectively. The transport of silica NPs across the BeWo cells was also limited, with an apparent permeability of only 1.54 × 10−6 ± 1.56 × 10−6 cm/sec. Using confocal microscopy, there was visual confirmation of particle accumulation in both BeWo cells and in perfused placental tissue. Despite the low transfer of silica NPs to the fetal compartment, questions regarding biocompatibility could limit the application of unmodified silica NPs in biomedical imaging or therapy.

Keywords: Transport, BeWo cells, Placental perfusion, Nanotoxicology, In vitro

Introduction

Nanomedicine is an emerging and rapidly growing area of nanotechnology. Diverse sets of nanoparticles (NPs) are under investigation for both diagnostic and therapeutic medical applications, such as medical imaging, cancer therapy, and drug delivery (Sandhiya et al. 2009). Nanomedicine includes diagnostic applications of NPs such as MRI contrast enhancement, biosensors and in vivo imaging, as well as advantages for drug delivery agents due to increased bioavailability and potentially targeted drug delivery (Sandhiya et al. 2009; Gonçalves et al. 2012).

Despite these and other exciting advances in nanomedicine, it is known that certain nanomaterials can cause toxicological responses and adverse health effects (Johnston et al. 2012). Therefore, it is important to investigate the unknown impacts such as toxicological effects and biodistribution of NPs having medical applications. To this end, the FP7 NanoTEST project was designed to assess these risks, with particular attention focused on understanding the potential interactions of NPs with cells, tissues, and organs in exposed humans (Dusinska et al. 2009a, Dusinska et al. 2009b). The assessment of potential biodistributive and toxicological profiles of nanomaterials can serve to promote the safe and responsible use of NPs in future biomedical applications.

When considering the potential impact of NP exposure, an organ of particular interest is the placenta. The developing fetus is especially vulnerable to toxic effects of medicine, and adverse events during fetal development may lead to significant long-term effects (Saunders 2009, Buerki-Thurnherr et al. 2012). Such adverse events may include placental inflammation associated with spontaneous abortion, fetal infections, placental oxidative stress, preeclampsia, and fetal growth retardation. Even though most pregnant women avoid medical treatment if possible, some diseases require treatment even during pregnancy. Therefore, it is of great importance to test the placental transport properties of medically applied NPs in order to avoid unnecessary fetal exposure. Furthermore, if safety is established, it might also be possible to use NPs for in utero treatment of the fetus (Rytting and Ahmed 2013).

Silica NPs have gained increasing attention as potential drug carriers or imaging agents. Properties such as tunable size and shape, high surface area, and large pore volume make mesoporous silica NPs particularly advantageous for controlled drug release (Slowing et al. 2008; Mamaeva et al. 2012) In addition to drug delivery applications (Galagudza et al. 2012), silica NPs are also under investigation for bone tissue engineering (Ganesh et al. 2012) and as bioprobes for biomedical imaging applications (Chen et al. 2012).

To date, limited data are available in the literature concerning the fate of silica NPs in pregnancy. Upon injection of 70-nm, 300-nm, and 1000-nm silica NPs into pregnant mice, Yamashita et al. observed that only the 70-nm particles were distributed in the placenta. At a dose of 0.8 mg per mouse, the 70-nm silica NPs resulted in significantly lower maternal body weight, uterine weight, and fetal weight, whereas the larger particles induced no such changes. However, these authors report that when 70-nm particles coated with either COOH or NH2 functional groups were administered to the pregnant mice, the maternal weights, uterine weights, and fetal weights did not differ from the controls. The authors suggest that the uncoated silica NPs may have induced complement activation or oxidative stress (Yamashita et al. 2011). Nevertheless, due to structural and functional differences between mouse placenta and human placenta (Ala-Kokko et al. 2000), it is important to investigate the distribution of silica NPs using models of human placenta.

The in vitro BeWo b30 cell model is a human choriocarcinoma cell line which represents the rate-limiting barrier for maternal-fetal exchange within the human placenta (Rytting et al. 2007). This model can be used for placental transport, metabolism, and toxicological studies and has been utilized to predict chemical exposure in pregnancy (Bode et al. 2006; Mitra and Audus, 2009; Mørck et al. 2010; Cartwright et al. 2012).

The ex vivo placental perfusion model is a transport model representing the complete human placental tissue structure and is therefore closer to the in vivo situation (Poulsen et al. 2009). Nevertheless, this model is time-consuming and the experiments can be challenging due to the need for fresh placental tissue (Mathiesen et al. 2010). Where the availability of fresh placental tissue is limited, the in vitro cell culture model may be an acceptable alternative, as long as one understands the utilities and the limitations of each model. A thorough comparison of maternal-fetal transfer data utilizing both the BeWo b30 cell model and ex vivo placental perfusion experiments was performed previously, and readers are referred to the work of Poulsen et al. (2009) for a detailed discussion of the advantages and disadvantages of both experimental models. Nevertheless, it should be noted that while the aforementioned report (Poulsen et al. 2009) compares the maternal-to-fetal transfer of small, low molecular weight compounds, this work utilizes both models to study the transplacental transfer of silica NPs.

The transplacental transport of silica NPs was investigated as part of the NanoTEST project in order to predict the fetal exposure to this type of nanomaterial subsequent to the possible presence of NPs in the maternal circulation during pregnancy. These experiments were carried out in parallel both in BeWo cells and in ex vivo placental perfusion to compare the two models. In addition, we have also investigated the effects of silica NPs on trophoblast cell viability.

Materials and Methods

Nanoparticle Characterization

Silica NPs (corpuscular, plain coating, Microspheres-Nanospheres, Cold Spring, NY, USA) were supplied via the EU FP7 NanoTEST Project. The particles were labeled with rhodamine and provided in two sizes: 25 nm and 50 nm, each in a stock concentration of 25 mg/mL. Initial characterization of the NPs was performed by Dr. Lucienne Juillerat (University Institute of Pathology, CHUV, Lausanne, Switzerland), who also provided the NP dispersion protocol. Characterization work carried out in collaboration with NanoTEST project colleagues (see Guadagnini et al. 2013) demonstrated BET surface area measurement readings of 159 m2/g for the 25-nm particles, and 87 m2/g for the 50-nm particles. The uncoated, amorphous silica particles were analyzed by transmission electron microscopy (TEM) and were found to have a pseudo-spherical shape. TEM measurements showed that the 25-nm particles were in a size range of 15–30 nm; the 50-nm particles had diameters in the range of 25–50 nm. Dynamic light scattering measurements of the NPs as supplied revealed average hydrodynamic diameter values of 23 nm for the 25-nm particles, and 38 nm for the 50-nm particles.

To assess the stability of the silica NP suspensions in terms of potential aggregation in cell culture media, the NPs were dispersed in DMEM-F12 without fetal bovine serum at a concentration of 240 μg/mL (to match the experimental conditions of Guadagnini et al.) and stirred at 50 rpm at 37°C under sterile conditions, together with control samples of medium without NPs. Samples at various time points were analyzed with dynamic light scattering using a Malvern High Performance Particle Sizer with non-invasive back-scatter optics. Similar measurements were also made for the silica NPs dispersed in DMEM-F12 containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) according to the aforementioned protocol, except that the NPs were at a concentration of 100 μg/mL in order to match the experimental conditions of this work.

Analysis

The detection limit was measured in BeWo cell transport medium and in fetal and maternal perfusate and calculated statistically as the lowest detectable silica NP concentration different from media or perfusate alone, with a p-value lower than 0.05 using the Student’s t-test. By fluorescence detection (details below), the detection limits for the BeWo cell and placental perfusion experiments were determined to be 1 μg/mL and 2.5 μg/mL, respectively. For detection of silica NP concentrations, 100 μL samples from either BeWo cell transport experiments or placental perfusion experiments were placed in a 96-well plate and analyzed for fluorescence in a Fluoroskan Ascent FL (Thermo Electron Corporation, Vantaa, Finland) with filter settings: λex = 544 nm and λem = 590 nm. Antipyrine concentrations were determined with a LaChrom HPLC system equipped with a C18 column as described previously (Mose et al. 2007; 2008).

Cell culture

The choriocarcinoma BeWo b30 cell line was obtained from Prof. Margaret Saunders (Bioengineering, Innovation, & Research Hub (BIRCH), St. Michael’s Hospital, Bristol NHS Foundation Trust, Bristol, UK) with permission from Dr. Alan Schwartz (Washington University, St. Louis, MO, USA). Cells were cultured in DMEM-F12 (Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium/Ham’s nutrient mixture F12, Sigma-Aldrich, Schnelldorf, Germany) with phenol red and supplemented with the following: 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Biological Industries, Kubitz Beit Haemek, Israel), 4 mM L-Glutamine (Panum Institute, Copenhagen University), and 1% Penicillin/Streptomycin (Penicillin 20 000 IU/mL, Streptomycin 5 mg/mL, Panum Institute, Copenhagen University). The cells were cultured and experiments were performed under sterile conditions at 37°C with 5% CO2 in a humidified atmosphere. At 75–80% confluence, cells were subcultured using trypsin-EDTA solution (Sigma-Aldrich, Schnelldorf, Germany). Experiments were conducted in supplemented DMEM-F12 media without phenol red.

Nanotoxicity

The BeWo b30 cells were seeded in 96-well plates at a density of 10 000 cells/well and grown for 24 h until semiconfluent. The cells were then exposed to the silica NPs in different concentrations between 0 and 500 μg/mL for 24 h. Triton X-100 (Applichem, Darmstadt, Germany), 0.1% v/v in media was used as positive control. The NPs were removed and the cells were washed 3 times in PBS. 100 μL of MTT (3-(4,5-dimethyl-thiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl-tetrazolium bromide) in a concentration of 0.5 mg/mL was then added to each well. After 2 h incubation, the MTT was removed and the crystals were dissolved in 100 μL of DMSO (Sigma-Aldrich, Ayershire, UK) per well. The plates were shaken at 900 rpm for 1 min and absorbance was measured at 550 nm using a Multiscan FC plate reader (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Denmark).

Nanoparticle stability

The nature of NPs necessitates some optimization of each experimental model in order to minimize problems such as agglomeration, sticking to surfaces, or in this case, potential reductions in the photostability of the fluorescently labeled NPs. Silica NPs diluted to 100 μg/mL in transport media (with and without supplements and cell debris) were placed in different tubes and plates—1.5 mL polypropylene reaction tubes, 15 mL polypropylene tubes, 96-well polystyrene plates, 12-well polystyrene plates (Greiner Bio One, Frickenhausen, Germany), and glass vials (Hounisen, Denmark)—and placed at 4°C, 25°C and 37°C. At different timepoints (0, 2, 4, 6, 8, and 24 h), the concentration in 100 μL samples from each tube or plate was determined using the Fluoroskan Ascent FL. The stability tests were performed in detail on the 25-nm silica NPs, while the 50-nm silica NPs were tested with fewer variables in terms of different tubes, media and temperature settings.

BeWo cell transport assay

BeWo b30 cells were seeded at a density of 100 000 cells/cm2 onto uncoated polycarbonate membrane Transwell® inserts (pore size 3 μm, growth area 1.12 cm2, apical chamber 0.5 mL, basal chamber 1.5 mL) and grown to 100% confluence as described above. Before the transport study was started, the transepithelial electrical resistance (TEER) was measured using an EndOhm apparatus (World Precision Instruments, Stevenage, UK) to ensure that the cell monolayer was intact. The TEER values were in the range of 16–20 Ω·cm2 and these values did not decrease at the end of the transport experiments, which demonstrates that the barrier integrity of the cell monolayers remained intact throughout the study. Immediately before the start of the experiment, all media was removed from both chambers. At T0, 0.5 mL of silica NPs was added to the apical chamber at a concentration of 100 μg/mL and 1.5 mL of fresh media was added to the basolateral chamber. The transport studies were carried out under sterile conditions and with constant horizontal shaking (10 rpm) to simulate the fluid flow in vivo. At successive timepoints (2, 4, 6, 8, 12 and 24 h), a 100 μL sample was collected from the media in the basal chamber and 10 μL sample was collected from the media in the apical chamber and placed in a 96-well plate. The 10 μL sample from the apical chamber was mixed with 50 μL of fresh media in the microplate to ensure that the bottom of the well was covered. The basal chamber was refilled with 100 μL of fresh media to avoid a volume decrease due to sampling. The small sample volume removed from the apical chamber was not replenished so as to not dilute the donor concentration. After the last sampling at 24 h, the TEER was measured again and the cells were washed 3 times in ice-cold HBSS (Hank’s Balanced Salt Solution, Sigma Aldrich, Schnelldorf, Germany) before the filters were cut out and placed in a 24-well plate. Each filter was covered in 1 mL lysing solution (0.5% Triton X-100 in 0.2 N NaOH) in order to lyse the cells. After 2 h of horizontal shaking (200 rpm) at 37°C, 100 μL lysate samples were analyzed for fluorescence to quantify NP uptake and attachment to the cells. The apparent permeability Pe of the NPs across the cell monolayer was calculated as previously described in Cartwright et al. (2012).

Placental perfusion

A total number of six term placentas were collected from uncomplicated pregnancies and births after elective caesarean sections or vaginal delivery at the University Hospital of Copenhagen. Informed written consent was obtained prior to or at the time of birth. The project was approved by the Ethical Committees in the Municipalities of Copenhagen and Frederiksberg (KF 01–145/03 + KF (11) 260063), and by the Danish Data Protection Agency. A dually perfused, closed system was used as previously described in detail (Mathiesen et al. 2010). Briefly, immediately after birth, umbilical arteries were flushed with Krebs Ringer buffer containing heparin (5000 IU/mL) and glucose (9 mM). The fetal circulation was re-established by cannulating an appropriate vascular unit. Two blunt cannulae were placed into the intervillous space representing the maternal circulation. The perfusions were performed with DMEM F12 cell culture media supplemented with penicillin-streptomycin, L-glutamine, heparin (5000 IU/mL), and human serum albumin (30 g/L in the maternal compartment and 40 g/L in the fetal compartment). Flow in the fetal circulation was 3 mL/min and 9 mL/min in the maternal circulation, and both compartments had a volume of 100 mL at T0. The maternal medium was gassed with 95% O2/5% CO2 and the fetal medium was gassed with 95% N2/5% CO2 to maintain oxygen levels in the maternal medium between 25–35 kPa and between 10–15 kPa in the fetal medium. Silica NPs (100 μg/mL) and the positive control substance antipyrine (100 mg/mL) were added simultaneously to the maternal medium to obtain a concentration of 100 μg/mL and 100 mg/mL resepctively. Antipyrine is a positive control for system setup and flow to ensure the correct position of maternal cannulae with the fetal unit. 0.6 mL samples were collected from both circulations prior to the introduction of the NPs and then at the following time points: 0, 2, 30, 60, 120, 180, 240, 270, 300, 330, and 360 min.

As a control for unspecific binding to the tubing and other perfusion equipment, blank perfusions were conducted with a closed maternal circulation without fetal circulation or placenta in the perfusion chamber. Antipyrine and silica NPs were added to the maternal medium and the blank perfusions were conducted as described above.

Quality markers were used to ensure tissue viability and optimal flow conditions during perfusion. These quality markers include: fetal-to-maternal antipyrine ratio > 0.75 after 2 hours of perfusion, fetal leakage less than 3 mL/h, oxygen transfer, physiological pH, glucose consumption, and lactate production. Oxygen tension, pH, glucose and lactate levels were measured by an ABLflex90 blood and gas analyzer (Radiometer, Denmark). Tissue samples (1×1×1 cm) from before and after perfusion were saved in formalin (10%) for histological analysis.

Microscopy

Both cells and tissue were stained with Hoechst 34580 (Invitrogen, DK) as a nuclear stain and with Wheat Germ Agglutinin Alexa 647 (WGA-647) (Invitrogen, DK) as a membrane stain. For both cell and tissue images, staining was observed using a Zeiss LSM 780 confocal system on an inverted stand with a 63x oil DIC Plan-Apochromat objective. Imaging parameters were selected to optimize resolution and images. Fluorophore and background spectra were acquired by lambda scans before the images were obtained using linear unmixing and Zen software from Zeiss. The lambda scans showed that the placental tissue has high autofluorescence, probably caused in part by lipofuscin-like lysosomal inclusion bodies in the tissue, with autofluorescence in a spectral region close to that of the silica NPs. Therefore, the spectral analysis of the tissue and fluorophores was carried out carefully to avoid mistaking these lipofuscin-like bodies for the silica NPs. While there is a slight possibility that this adjustment of spectral settings to remove tissue autofluorescence might result in the inability to detect some of the smallest silica NPs, larger particles and agglomerates were clearly visible.

BeWo cells

After the 24 h time point of the transport study, the cells were washed 3 times in ice-cold HBSS to stop the transport and incubated in 5 μg/mL Hoechst 34580 for 30 min, in 5 μg/mL WGA-647 for 2 hours, and then fixed in 37% formaldehyde (Sigma Aldrich, Ayershire, UK) for 30 min. Between each step, the cells were washed 3 times in PBS. The filters were cut out of the Transwell® inserts and mounted on glass slides with the cells side up using a drop of Vectashield mounting medium (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA).

Placental tissue

Placental samples were cut out and saved from both perfused placentas and pre-perfused placentas (negative control). They were kept in 10% formalin until they were paraffinized and cut on a microtome to a thickness of 10 μm. The tissue was mounted on glass slides and deparaffinized in xylene (Applichem GmbH, Germany). The deparaffinized tissue was incubated in Hoechst 34580 for 30 min and in WGA-647 for 2 hours. Between each step they were washed 3 times in PBS. The tissue was mounted on glass slides using a drop of Vectashield mounting medium.

Results

Nanotoxicity

The MTT assay results in Figure 1 show that for both sizes of particles studied (particle diameters 25 nm and 50 nm), the silica NPs cause cytotoxic effects to the BeWo cells at concentrations above 100 μg/mL. For this reason, all cell transport and perfusion experiments were performed using a NP concentration of 100 μg/mL. In this manner, any interference with trophoblast barrier integrity—and thus, any interference with transplacental transport results—due to cytotoxicity was avoided.

Figure 1.

Viability of BeWo b30 cells as determined by the MTT assay after 24-hour exposure to silica nanoparticles added at different concentrations from 0 – 500 μg/ml. 0.1% Triton X-100 was used as a positive control for cytotoxicity.

Nanoparticle stability

Table 1 shows that when the particles were dispersed in cell culture medium (DMEM-F12 without fetal bovine serum), the measured Z-average particles sizes were 31 nm for the 25-nm particles and 40 nm for the 50-nm particles. These values remained relatively stable for at least 7.5 hours, but less than 20 hours. When these particles were dispersed in DMEM-F12 containing 10% FBS, however, interpretation of dynamic light scattering results is not straightforward. Serum proteins with hydrodynamic diameters similar to that of the NPs confound the analysis of NP size distributions when low concentrations of nanoparticles are dispersed in cell culture medium containing FBS (see Hondow et al. 2012).

Table 1.

Particle size stability for 25- and 50-nm silica nanoparticles dispersed in DMEM-F12. The nanoparticles were dispersed in the medium (without fetal bovine serum) at a concentration of 240 μg/mL. The nanosuspensions were stirred at 50 rpm at 37°C in sterile conditions and then sampled at the indicated times. The data represent the average ± standard deviation of three measurements consisting of at least 10 runs per measurement. It should be noted that no peaks were detected for blank DMEM-F12 containing no FBS and no nanoparticles.

| 25-nm Silica Nanoparticles | ||

|---|---|---|

| Time (hours) | Z-average particle size (nm) | Polydispersity index |

| 0 | 31 ± 2 | 0.36 ± 0.10 |

| 2 | 42 ± 1 | 0.37 ± 0.01 |

| 4 | 29 ± 2 | 0.33 ± 0.04 |

| 7.5 | 24 ± 1 | 0.31 ± 0.05 |

| 20 | 64 ± 9 | 0.68 ± 0.13 |

| 50-nm Silica Nanoparticles | ||

|---|---|---|

| Time (hours) | Z-average particle size (nm) | Polydispersity index |

| 0 | 40 ± 1 | 0.23 ± 0.02 |

| 2 | 50 ± 2 | 0.30 ± 0.01 |

| 4 | 46 ± 1 | 0.31 ± 0.01 |

| 7.5 | 46 ± 2 | 0.32 ± 0.01 |

| 20 | 73 ± 10 | 0.67 ± 0.09 |

Table 2 shows that dynamic light scattering measurements of blank DMEM-F12 containing 10% FBS (but containing no NPs) results in multiple size distribution peaks, with specific size intensity peaks around 8 nm, 40 nm, and larger. (When the polydispersity index is high due to multiple peaks, the mean size value is less meaningful and the individual peak values are worthy of inspection.) When the 25- and 50-nm silica NPs were dispersed in the media containing FBS, these same peak intensities around 8 nm, 40 nm, and larger were still observed. Because the serum protein peak around 40 nm is of the same magnitude as the expected particle sizes of both the 25- and the 50-nm silica NPs, no conclusions can be made regarding the particle size measurements of these silica NPs by dynamic light scattering when the NPs are dispersed at this low concentration in media containing FBS. Nevertheless, it is interesting to note that the peak area intensity values had shifted somewhat compared to those of the blank media, which may reflect the formation of a protein layer on the nanoparticle surfaces upon contact with serum proteins, referred to by Lesniak et al. (2012) as a protein corona.

Table 2.

Particle size measurements for 25- and 50-nm silica nanoparticles dispersed at a concentration of 100 μg/mL in DMEM-F12 containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS). The nanosuspensions were stirred at 50 rpm at 37°C in sterile conditions and then sampled at the indicated times. The data represent the average ± s.d. of 3 measurements consisting of at least 10 runs each. Only data for the three most prominent size distribution peaks are shown, i.e., the total peak area intensity will not add up to 100% if there were more than 3 peaks. Similar measurements of blank DMEM-F12 + 10% FBS (containing no nanoparticles) are presented first for comparison. Mean size = Z-average particle size. PDI = polydispersity index.

| Blank DMEM-F12 + 10% FBS | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time (h) | Mean size (nm) | PDI | Peak 1 (nm) | Peak 2 (nm) | Peak 3 (nm) | Peak 1 Area (%) | Peak 2 Area (%) | Peak 3 Area (%) |

| 0 | 18 ± 5 | 0.48 ± 0.18 | 8 ± 0 | 45 ± 2 | 735 ± 295 | 48 ± 2 | 38 ± 2 | 10 ± 4 |

| 2 | 23 ± 5 | 0.55 ± 0.13 | 32 ± 7 | 8 ± 1 | 519 ± 295 | 36 ± 3 | 34 ± 5 | 21 ± 4 |

| 4 | 20 ± 1 | 0.56 ± 0.07 | 35 ± 3 | 7 ± 1 | 458 ± 63 | 43 ± 4 | 32 ± 3 | 19 ± 3 |

| 8 | 12 ± 0 | 0.47 ± 0.05 | 8 ± 1 | 40 ± 20 | 5370 ± 4534 | 54 ± 10 | 35 ± 5 | 6 ± 4 |

| 16 | 13 ± 2 | 0.34 ± 0.09 | 8 ± 2 | 37 ± 10 | 5598 ± 4209 | 56 ± 9 | 33 ± 11 | 6 ± 2 |

| 24 | 13 ± 0 | 0.55 ± 0.04 | 7 ± 1 | 40 ± 15 | 1675 ± 1902 | 46 ± 11 | 39 ± 5 | 11 ± 3 |

| 25 nm Silica nanoparticles in DMEM-F12 + 10% FBS | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time (h) | Mean size (nm) | PDI | Peak 1 (nm) | Peak 2 (nm) | Peak 3 (nm) | Peak 1 Area (%) | Peak 2 Area (%) | Peak 3 Area (%) |

| 0 | 86 ± 4 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 307 ± 14 | 34 ± 2 | 7 ± 1 | 74 ± 2 | 14 ± 2 | 7 ± 1 |

| 2 | 60 ± 2 | 0.59 ± 0.04 | 196 ± 80 | 40 ± 10 | 8 ± 1 | 60 ± 14 | 26 ± 16 | 8 ± 1 |

| 4 | 61 ± 1 | 0.55 ± 0.04 | 157 ± 18 | 43 ± 12 | 8 ± 1 | 57 ± 11 | 31 ± 9 | 6 ± 1 |

| 8 | 65 ± 1 | 0.53 ± 0.01 | 84 ± 14 | 321 ± 89 | 18 ± 9 | 57 ± 3 | 25 ± 7 | 8 ± 0 |

| 16 | 100 ± 0 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 649 ± 211 | 112 ± 26 | 28 ± 8 | 49 ± 7 | 33 ± 8 | 7 ± 2 |

| 24 | 94 ± 2 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 266 ± 140 | 56 ± 24 | 2901 ± 3162 | 46 ± 2 | 20 ± 8 | 20 ± 9 |

| 50 nm Silica nanoparticles in DMEM-F12 + 10% FBS | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time (h) | Mean size (nm) | PDI | Peak 1 (nm) | Peak 2 (nm) | Peak 3 (nm) | Peak 1 Area (%) | Peak 2 Area (%) | Peak 3 Area (%) |

| 0 | 50 ± 1 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 231 ± 45 | 39 ± 9 | 7 ± 0 | 59 ± 4 | 23 ± 5 | 11 ± 1 |

| 2 | 49 ± 0 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 86 ± 32 | 467 ± 289 | 20 ± 22 | 43 ± 8 | 36 ± 14 | 12 ± 3 |

| 4 | 53 ± 1 | 0.63 ± 0.04 | 143 ± 57 | 33 ± 11 | 7 ± 0 | 65 ± 25 | 18 ± 7 | 11 ± 1 |

| 8 | 52 ± 2 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 112 ± 53 | 931 ± 718 | 25 ± 17 | 46 ± 15 | 29 ± 21 | 14 ± 3 |

| 16 | 52 ± 6 | 0.89 ± 0.19 | 311 ± 223 | 56 ± 53 | 6 ± 1 | 55 ± 30 | 32 ± 27 | 8 ± 3 |

| 24 | 35 ± 3 | 0.90 ± 0.18 | 117 ± 15 | 17 ± 6 | 6 ± 1 | 66 ± 3 | 17 ± 4 | 11 ± 3 |

According to the fluorescence measurements, the silica NP concentrations in the vials and plates kept at 4°C for 24 h did not decrease (105 ± 8%), although the concentrations in the vials and plates kept at 25°C had decreased slightly after 24 h (93 ± 3%). The concentration in the vials and plates kept at 37°C for 24 h had decreased to 73% (a decrease of 1.1% per hour) in the 12-well plate, 66–67% in the glass vials, 53% in the 1.5 mL reaction tube and 25% in the 15 mL tube. The 25-nm and 50-nm silica NPs showed similar concentration decreases. Supplements and cell debris in the media had no effect on these observed decreases in concentration.

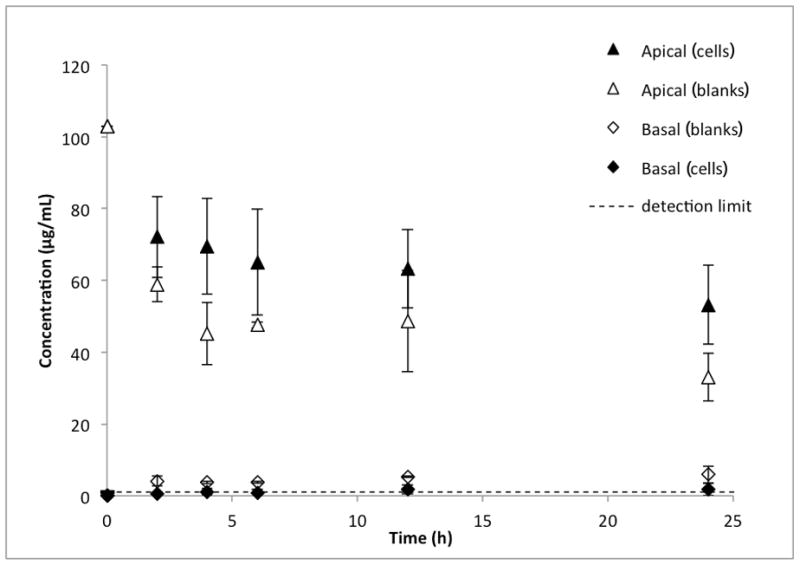

Transport across BeWo cells

Figure 2 shows that after 24 h, the concentration of silica NPs in the apical chamber decreased to 53 ± 11% of the initial concentration. Taking into account the loss of 27% of the fluorescence in 24 h demonstrated in the 12-well plate stability studies above, this equates to 73 ± 15% of the initial NP concentration remaining in the apical chamber at the end of the experiments. The concentration in the basal chamber increased slightly, reaching detectable levels after 12 hours, followed by a slight decrease in concentration after 24 hours. The apparent permeability of the 25-nm silica NPs was 1.54 × 10−6 ± 1.56 × 10−6 cm/sec.

Figure 2.

Transport of 25-nm silica nanoparticles across BeWo b30 cell monolayers (n=6). The initial concentration in the apical chamber was 100 μg/ml. The closed triangles represent the concentration of the silica nanoparticles in the apical (maternal) compartment at each time point in Transwell® inserts containing the BeWo cells. The closed diamonds represent the nanoparticle concentrations in the basolateral (fetal) side of the cell monolayers. The open triangles represent the apical concentrations in blank experiments, i.e., in Transwells containing no cells. The open diamonds represent the basolateral concentrations in the blank experiments. The blank experiments (transport across Transwell membranes without any cells) were necessary to calculate the apparent permeability across the cell monolayers (Pe, see text for details).

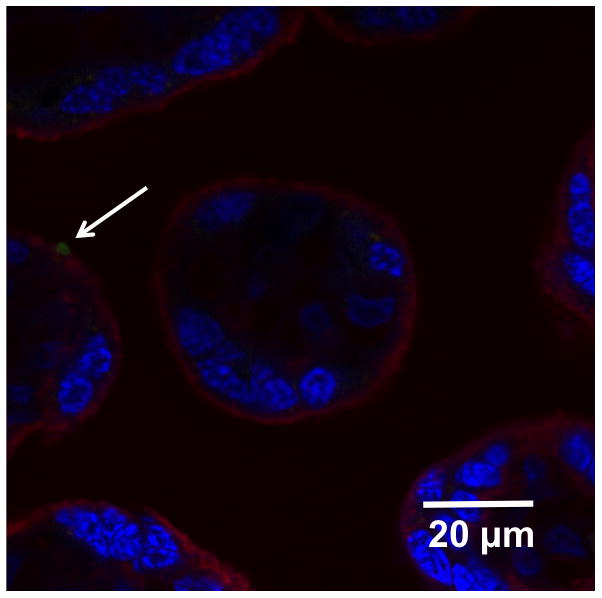

Analysis of nanoparticles in the BeWo monolayer

Although the cellular uptake of NPs in BeWo cell lysate was below the limit of detection (1 μg/mL) and could therefore not be quantified, Figure 3 demonstrates qualitatively the presence of the NPs within the cells after 24 hours.

Figure 3.

Confocal images of 25-nm silica nanoparticle transport through a BeWo cell monolayer. A: top section of cells, B: upper-middle section of cells, C: middle section of cells, D: lower-middle section of cells, E: basal section of cells. Red: cell membrane, Blue: nuclei, Yellow: silica nanoparticles, Light red dots in D and E: filter pores.

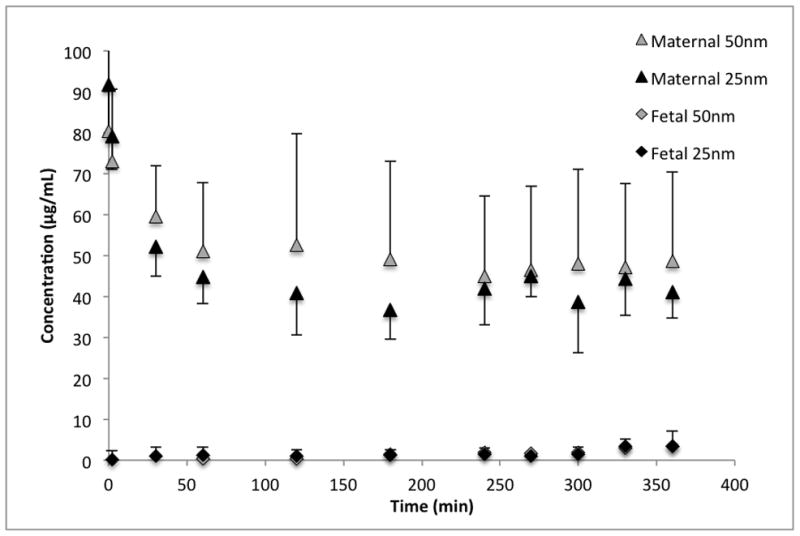

Placental perfusion of silica nanoparticles

During the system binding study (control experiment without placental tissue), the concentration of silica NPs declined in the perfusate, but to a different extent for each particle size tested. At the end of the 6-hour system binding studies, 82% of the 25-nm silica NPs remained in the perfusate, whereas only 65% of the 50-nm particles remained in the perfusate.

Six successful perfusions were performed, three with each particle size. Antipyrine crossed the placenta rapidly—as expected—with a fetal/maternal ratio of 0.97 ± 0.10 after 120 min of perfusion. The silica NPs crossed the placenta to a very limited extent, reaching detectable levels (2.5 μg/mL) in the fetal circulation only after 5 hours of perfusion (see Figure 4). After 6 hours of perfusion, 4.2 ± 4.9% and 4.6 ± 2.4% of the initial maternal concentration of 25-nm and 50-nm NPs, respectively, had passed to the fetal perfusate.

Figure 4.

Transport of 25-nm (n=3) and 50-nm (n=3) silica nanoparticles across perfused human placenta. The initial concentration in the maternal perfusate was 100μg/ml.

The substantial decrease in NP concentration in the maternal perfusate during the 6-hour perfusion study without a corresponding magnitude of transfer of the NPs to the fetal perfusate suggests some accumulation of NPs in the placental tissue. Accordingly, Figure 5 demonstrates the presence of agglomerated NPs at the outer surface of a chorionic villus following a placental perfusion experiment.

Figure 5.

Confocal image of placental tissue after 6 hours of perfusion with 25-nm silica nanoparticles. Red: cell membrane, Blue: cell nuclei, Green: silica nanoparticles.

Discussion

In this study we have investigated the transplacental permeability of silica NPs in two models of the human placental barrier. In addition, we have investigated the effects of silica NPs on placental trophoblast cell viability. This information is essential to predict how maternal exposure to silica NPs during pregnancy could influence the fetus.

We observed that at concentrations above 100 μg/mL, the silica NPs caused a decrease in cell viability for BeWo cells, an in vitro model of human placental trophoblast cells. Nanotoxicological effects of silica NPs have been reported by other authors, as well. For example, Shi et al. (2012) suggested that lipid peroxidation plays a role in the induction of cytotoxicity by silica NPs in MCF-7 cells. General observations from the literature indicate that amorphous silica is less toxic than crystalline silica (Jaganathan and Godin 2012), and mesoporous silica NPs are less toxic than colloidal silica NPs (Lee et al. 2011). It has also been shown that surface modification of silica NPs can alter the effects of such particles on cell proliferation or oxidative stress (Tsutsumi and Yoshioka 2011; Stępnik et al. 2012). It should be noted that Fisichella et al. (2009) had observed that mesoporous silica nanoparticles can interfere with MTT assays in other cell types, resulting in overestimations of cytotoxicity. Nevertheless, this would not affect our conclusion and the purpose of our MTT study, i.e., that the concentration of nanoparticles employed in our transport studies (100 μg/mL) was not cytotoxic.

In this work, we observed that the transplacental transport of silica NPs was limited. In both the BeWo b30 cell line and in ex vivo human placental perfusion studies, the concentration of silica NPs reaching the fetal compartment did not even attain the lower limits of detection until the later timepoints. The accumulation of the silica NPs into the trophoblast cells was also limited. It is clear from this work and from similar studies reported in the literature that the transplacental transport of NPs is dependent on the nanomaterial. Myllynen et al. did not observe any detectable transport of PEGylated gold NPs across the placenta (Myllynen et al. 2008). Menjoge et al. reported low but quantifiable transfer of polyamidoamine dendrimers from maternal to fetal perfusate (Menjoge et al. 2011). On the other hand, the transplacental transport of polystyrene NPs has been observed in both BeWo cells and in perfused placenta, and in both cases, the transport was shown to be size-dependent (Wick et al. 2010; Cartwright et al. 2012).

Although fluorescence microscopy qualitatively revealed the presence of silica NPs in the BeWo cells, the quantitative uptake was below the limit of detection. The observation of agglomerated NPs on the outer surface of a chorionic villous following a placental perfusion experiment (Figure 5) is in good agreement with the observed apical accumulation of particles in the BeWo cells (Figure 3). The apparently lower qualitative uptake of the silica NPs in the perfused placental tissue compared to the BeWo cells can be explained by the differences in exposure on the basis of mass per surface area. The total exchange area of a term human placenta is approximately 13 m2 (Larsen et al. 1995; Syme et al. 2004), but the total exchange area in a single Transwell® insert containing BeWo cells is 1.12 cm2. The average weight of the placentas used in these perfusion experiments was 773 g, and the average weight of the perfused cotyledons was 25 g. Even though the NP concentration in both systems was 100 μg/mL, the volume in the donor (maternal) compartment is 100 mL in the perfusion experiments, but only 0.5 mL in the BeWo cell studies. Therefore, on the basis of mass per surface area, the BeWo trophoblast cells are exposed to approximately 45 μg/cm2 of silica NPs while the perfused placental trophoblast cells are exposed to approximately 2.4 μg/cm2. This can explain the relatively lower qualitative uptake of the particles in the perfused placental tissue. It should be noted that it is not possible to calculate the area of a perfused placental cotyledon prior to the experiments because the precise weight of the cotyledon is not known until after the experiment is finished.

Another difference between the two models employed in this study is the possibility for the NPs to agglomerate or adsorb to physical components of the experimental systems. More binding to polypropylene was observed compared to polystyrene or glass components. In comparison to the experimental setup for the BeWo cells, the placental perfusion system involves more containers and tubing required to pump the flow of the maternal and fetal perfusates to the placental tissue. Control experiments without cells or in the absence of placental tissue were carried out in order to account for these differences as well as any loss of fluorescence over time. No significant differences in transport of substances were observed upon consideration of placental source, as reported in the comparison of placentas obtained from caesarean section versus vaginal deliveries in the inter-laboratory investigations of Myllynen et al. (2010), which included placentas perfused in our laboratory. Some of the loss of fluorescence observed in the stability studies could be due to fluorescence quenching in particle agglomerates or the sedimentation of such agglomerates out of suspension.

Conclusions

Limited transplacental transport of silica NPs was observed in both models of maternal-fetal transfer in human placenta. Therefore, limited fetal exposure to silica NPs would be expected in the case of maternal administration of such particles for biomedical imaging or therapeutic purposes. This could prove beneficial in the diagnosis or treatment of maternal disease during pregnancy when restricted fetal exposure is desired. Nevertheless, the observed toxicity of silica NPs at high concentrations may limit their future medical applications. Since mesoporous silica NPs or particles with surface modifications are less likely to induce toxic responses, it is expected that such products may be more likely to find application in future medicine. Therefore, it will be necessary to investigate the influence of pore architecture and NP surface properties on the transport of silica NPs across the placenta.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful for the support of Maria Dusinska, Lucienne Juillerat, Margaret Saunders, and Antonio Marcomini in their leadership roles within the NanoTEST Consortium. The Core Facility for Integrated Microscopy (http://www.cfim.ku.dk) is acknowledged for support with confocal microscopy.

The authors acknowledge funding provided through the NanoTEST Consortium, supported by the European Commission FP7 (Health-2007-2001.3-4, contract number 201335). M. S. P. is supported by the Institute of Public Health, Copenhagen University. E. R. is supported by a research career development award (K12HD052023: Building Interdisciplinary Research Careers in Women’s Health Program, BIRCWH) from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), the NICHD, and the Office of the Director (OD), National Institutes of Health (NIH).

Footnotes

Declaration of interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIAID, NICHD, OD, or the NIH.

References

- Ala-Kokko TI, Myllynen P, Vähäkangas K. Ex vivo perfusion of the human placental cotyledon: implications for anesthetic pharmacology. Int J Obstet Anesth. 2000;9:26–38. [Google Scholar]

- Bode CJ, Jin H, Rytting E, Silverstein PS, Young AM, Audus KL. In vitro models for studying trophoblast transcellular transport. Methods Mol Med. 2006;122:225–239. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-989-3:225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buerki-Thurnherr T, von Mandach U, Wick P. Knocking at the door of the unborn child: engineered nanoparticles at the human placental barrier. Swiss Med Wkly. 2012;142:w13559. doi: 10.4414/smw.2012.13559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cartwright L, Poulsen MS, Nielsen HM, Pojana G, Knudsen LE, Saunders M, Rytting E. In vitro placental model optimization for nanoparticle transport studies. Int j nanomedicine. 2012;7:497–510. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S26601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z-Z, Cai L, Dong X-M, Tang H-W, Pang D-W. Covalent conjugation of avidin with dye-doped silica nanopaticles and preparation of high density avidin nanoparticles as photostable bioprobes. Biosens Bioelectron. 2012;37:75–81. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2012.04.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dusinska M, Fjellsbo LM, Heimstad E, Harju M, Bartonova A, Tran L, Juillerat-Jeanneret L, Halamoda B, Marano F, Boland S, Saunders M, Cartwright L, Carreira S, Thawley S, Whelan M, Klein C, Housiadas C, Volkovova K, Tulinska J, Beno M, Sebekova K, Knudsen LE, Mose T, Castell JV, Vilà MR, Gombau L, Jepson M, Pojana G, Marcomini A. Development of methodology for alternative testing strategies for the assessment of the toxicological profile of nanoparticles used in medical diagnostics. NanoTEST – EC FP7 project. J Phys Conf Ser. 2009a;170:012039. [Google Scholar]

- Dusinska M, Fjellsbø L, Magdolenova Z, Rinna A, Runden Pran E, Bartonova A, Heimstad E, Harju M, Tran L, Ross B, Juillerat L, Halamoda Kenzaui B, Marano F, Boland S, Guadaginini R, Saunders M, Cartwright L, Carreira S, Whelan M, Kelin Ch, Worth A, Palosaari T, Burello E, Housiadas C, Pilou M, Volkovova K, Tulinska J, Kazimirova A, Barancokova M, Sebekova K, Hurbankova M, Kovacikova Z, Knudsen L, Poulsen M, Mose T, Vilà M, Gombau L, Fernandez B, Castell J, Marcomini A, Pojana G, Bilanicova D, Vallotto D. Testing strategies for the safety of nanoparticles used in medical applications. Nanomedicine (London) 2009b;4:605–607. doi: 10.2217/nnm.09.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galagudza M, Korolev Postnov, Naumisheva Uskov, Grigorova Shlyakhto E. Passive targeting of ischemic-reperfused myocardium with adenosine-loaded silica nanoparticles. Int J Nanomedicine. 2012;7:1671–1678. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S29511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisichella M, Dabboue H, Bhattacharyya S, Saboungi ML, Salvetat JP, Hevor T, Guerin M. Mesoporous silica nanoparticles enhance MTT formazan exocytosis in HeLa cells and astrocytes. Toxicol in Vitro. 2009;23:697–703. doi: 10.1016/j.tiv.2009.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganesh N, Jayakumar R, Koyakutty M, Mony U, Nair SV. Embedded Silica Nanoparticles in Poly(Caprolactone) Nanofibrous Scaffolds Enhanced Osteogenic Potential for Bone Tissue Engineering. Tissue Eng Part A. 2012;18:1867–1881. doi: 10.1089/ten.TEA.2012.0167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonçalves AS, Macedo AS, Souto EB. Therapeutic nanosystems for oncology nanomedicine. Clin Transl Oncol. 2012;14:883–890. doi: 10.1007/s12094-012-0912-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guadagnini R, Halamoda B, Cartwright L, Pojana G, Magdolenova Z, Bilanicova D, Saunders M, Juillerat-Jeanneret L, Marcomini A, Huk A, Dusinska M, Fjellsbø LM, Marano F, Boland S. Toxicity screenings of nanomaterials: challenges due to interference with assay processes and components of classic in vitro tests. Nanotoxicol. doi: 10.3109/17435390.2013.829590. this issue. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hondow N, Brydson R, Wang P, Holton MD, Brown MR, Rees P, Summer HD, Brown A. Quantitative characterization of nanoparticle agglomeration within biological media. J Nanopart Res. 2012;14:977. [Google Scholar]

- Jaganathan H, Godin B. Biocompatibility assessment of Si-based nano- and micro-particles. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2012;64:1800–1819. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2012.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston H, Brown D, Kermanizadeh A, Gubbins E, Stone V. Investigating the relationship between nanomaterial hazard and physicochemical properties: Informing the exploitation of nanomaterials within therapeutic and diagnostic applications. J Control Release. 2012;164:307–313. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2012.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsen LG, Clausen HV, Andersen B, Græm N. A stereologic study of postmature placentas fixed by dual perfusion. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1995;172:500–507. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(95)90563-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S, Yun H-S, Kim S-H. The comparative effects of mesoporous silica nanoparticles and colloidal silica on inflammation and apoptosis. Biomaterials. 2011;32:9434–9443. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.08.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lesniak A, Fenaroli F, Monopoli MP, Åberg C, Dawson KA, Salvati A. Effects of the presence or absence of a protein corona on silica nanoparticle uptake and impact on cells. ACS Nano. 2012;6:5845–5857. doi: 10.1021/nn300223w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mamaeva V, Sahlgren C, Lindén M. Mesoporous silica nanoparticles in medicine—Recent advances. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2012.07.018. epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathiesen L, Mose T, Mørck TJ, Nielsen JKS, Nielsen LK, Maroun LL, Dziegiel MH, Larsen LG, Knudsen LE. Quality assessment of a placental perfusion protocol. Reprod Toxicol. 2010;30:138–146. doi: 10.1016/j.reprotox.2010.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menjoge AR, Rinderknecht AL, Navath RS, Faridnia M, Kim CJ, Romero R, Miller RK, Kannan RM. Transfer of PAMAM dendrimers across human placenta: Prospects of its use as drug carrier during pregnancy. J Control Release. 2011;150:326–338. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2010.11.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitra P, Audus KL. Expression and functional activities of selected sulfotransferase isoforms in BeWo cells and primary cytotrophoblast cells. Biochem Pharmacol. 2009;78:1475–1482. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2009.07.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mose T, Kjaerstad MB, Mathiesen L, Nielsen JB, Edelfors S, Knudsen L. Placental Passage of Benzoic acid, Caffeine, and Glyphosate in an Ex Vivo Human Perfusion System. J Toxicol Environ Health A. 2008;71:984–991. doi: 10.1080/01932690801934513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mose T, Mortensen GK, Hedegaard M, Knudsen LE. Phthalate monoesters in perfusate from a dual placenta perfusion system, the placenta tissue and umbilical cord blood. Reprod Toxicol. 2007;23:83–91. doi: 10.1016/j.reprotox.2006.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myllynen P, Loughran M, Howard C, Sormunen R, Walsh A, Vähäkangas K. Kinetics of gold nanoparticles in the human placenta. Reprod Toxicol. 2008;26:130–137. doi: 10.1016/j.reprotox.2008.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myllynen P, Mathiesen L, Weimer M, Annola K, Immonen E, Karttunen V, Kummu M, Mørck TJ, Nielsen JKS, Knudsen LE, Vähäkangas K. Preliminary interlaboratory comparison of the ex vivo dual human placental perfusion system. Reprod Toxicol. 2010;30:94–102. doi: 10.1016/j.reprotox.2010.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mørck TJ, Sorda G, Bechi N, Rasmussen BS, Nielsen JB, Ietta F, Rytting E, Mathiesen L, Paulesu L, Knudsen LE. Placental transport and in vitro effects of Bisphenol A. Reprod Toxicol. 2010;30:131–137. doi: 10.1016/j.reprotox.2010.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oberdörster G, Stone V, Donaldson K. Toxicology of nanoparticles: A historical perspective. Nanotoxicol. 2007;1:2–25. [Google Scholar]

- Poulsen MS, Rytting E, Mose T, Knudsen LE. Modeling placental transport: correlation of in vitro BeWo cell permeability and ex vivo human placental perfusion. Toxicol In Vitro. 2009;23:1380–1386. doi: 10.1016/j.tiv.2009.07.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rytting E, Ahmed MS. Fetal drug therapy. In: Mattison DR, editor. Clinical pharmacology during pregnancy. London: Elsevier; 2013. pp. 55–72. [Google Scholar]

- Rytting E, Bryan J, Southard M, Audus KL. Low-affinity uptake of the fluorescent organic cation 4-(4-(dimethylamino)styryl)-N-methylpyridinium iodide (4-Di-1-ASP) in BeWo cells. Biochem Pharmacol. 2007;73:891–900. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2006.11.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandhiya S, Dkhar SA, Surendiran A. Emerging trends of nanomedicine - an overview. Fundam Clin Pharmacol. 2009;23:263–269. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-8206.2009.00692.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saunders M. Transplacental transport of nanomaterials. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Nanomed Nanobiotechnol. 2009;1:671–684. doi: 10.1002/wnan.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi J, Karlsson HL, Johansson K, Gogvadze V, Xiao L, Li J, Burks T, Garcia-Bennett A, Uheida A, Muhammed M, Mathur S, Morgenstern R, Kagan VE, Fadeel B. Microsomal Glutathione Transferase 1 Protects Against Toxicity Induced by Silica Nanoparticles but Not by Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles. ACS Nano. 2012;6:1925–1938. doi: 10.1021/nn2021056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slowing I, Viveroescoto J, Wu C, Lin V. Mesoporous silica nanoparticles as controlled release drug delivery and gene transfection carriers. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2008;60:1278–1288. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2008.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stępnik M, Arkusz J, Smok-Pieniążek A, Bratek-Skicki A, Salvati A, Lynch I, Dawson KA, Gromadzińska J, de Jong WH, Rydzyński K. Cytotoxic effects in 3T3-L1 mouse and WI-38 human fibroblasts following 72hour and 7day exposures to commercial silica nanoparticles. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2012;263:89–101. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2012.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Syme MR, Paxton JW, Keelan JA. Drug transfer and metabolism by the human placenta. Clin pharmacokinet. 2004;43:487–514. doi: 10.2165/00003088-200443080-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsutsumi Y, Yoshioka Y. Quantifying the biodistribution of nanoparticles. Nat Nanotechnol. 2011;6:755–755. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2011.220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wick P, Malek A, Manser P, Meili D, Maeder-Althaus X, Diener L, Diener P-A, Zisch A, Krug HF, von Mandach U. Barrier capacity of human placenta for nanosized materials. Environ Health Perspect. 2010;118:432–436. doi: 10.1289/ehp.0901200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamashita K, Yoshioka Y, Higashisaka K, Mimura K, Morishita Y, Nozaki M, Yoshida T, Ogura T, Nabeshi H, Nagano K, Abe Y, Kamada H, Monobe Y, Imazawa T, Aoshima H, Shishido K, Kawai Y, Mayumi T, Tsunoda S-I, Itoh N, Yoshikawa T, Yanagihara I, Saito S, Tsutsumi Y. Silica and titanium dioxide nanoparticles cause pregnancy complications in mice. Nat Nanotechnol. 2011;6:321–328. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2011.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]