Introduction

Both the size and composition of the U.S. foreign-born population have grown since 1960, rising from 9.7 million to nearly 40 million in 2010. Latin Americans were a major driver of this trend, as their numbers soared from less than one million in 1960 to nearly 19 million in 2010.1 The source countries also became more diverse, especially after 1970, when flows from Central America, Cuba, and Dominican Republic surged. These census-based stock measures, which combine recent and prior immigration as well as temporary and unauthorized residents, reveal little about the pathways to U.S. residence, the ebb and flow of migrants from specific countries, or the forces that produce and sustain the flows.

In this essay we provide an overview of immigration from Latin America since 1960, focusing on changes in both the size and composition of the major flows as well as the entry pathways to lawful permanent residence in the United States, with due attention to policy shifts. We argue that current migration streams have deep historical roots and that are related both to changes in U.S. immigration policy and to unequal and inconsistent enforcement of laws on the books, with myriad unintended consequences for sending and receiving communities. The concluding section reflects on the implications of Latin American immigration for the future of the nation, highlighting the growing importance of the children of immigrants for the future labor needs of an aging nation and worrisome signs about the thwarted integration prospects of recent and future immigrants in localities where anti-immigrant hostility is on the rise.

Historical Prelude and Policy Framework

Nearly a century before the English founded Jamestown (1607), Spanish settlements peppered the Americas. Even as they forged indelible Hispanic imprints in large swaths of the American Southwest, Spanish settlers Hispanicized the South American continent, later joined by the Portuguese, in an “Iberian enterprise” that R. D. Rumbaut describes as “one of the greatest and deepest convulsions in history… [an] epochal movement … that poured the occidental nations of Europe over … the New World.”2 As such, Spain began the first wave of migration to what became the United States of America, and also populated one of its future sources of immigrants.

The longstanding power struggle between Spain and England, which carried over to the Americas, is also relevant for understanding Latin American immigration to the United States. Although most Spanish colonies had achieved independence by the middle of the 19th century, the newly independent republics were weak politically and militarily, and vulnerable to external aggression. Given its proximity, Mexico proved an easy target for the expansionist aspirations of United States. Under the terms of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo that ended the U.S.-Mexican War (1846-1848) combined with the Gadsden Purchase, the United States acquired almost half of Mexico’s land. The significance of the annexation for contemporary immigration from Mexico cannot be overstated. Not only were social ties impervious to the newly drawn political boundary, but economic ties also were deepened as Mexican workers were recruited to satisfy chronic and temporary labor shortages during the 19th and 20th century—an asymmetrical exchange that was facilitated by the maintenance of a porous border. The Bracero Program, a guest worker program in force between 1942 and 1964, is a poignant example of U.S. growers’ dependence on Mexican labor facilitated both by legal contracts combined with growing reliance on unauthorized labor.

Fifty years after the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, the United States intervened in Cuba’s struggle for independence against the Spanish crown, which lost its last colonies in the Americas and the Pacific region. As part of the settlement, the United States acquired Puerto Rico, Guam, and the Philippines, and was ceded temporary control of Cuba. Both the U.S.-Mexico War and the Spanish American war established foundations for U.S.-bound migration. Mexico and Cuba have been top sending countries for most of the 20th century and into the 21st Century, with the Philippines ranked second since 1980.3 Notwithstanding intermittent travel barriers imposed by the Castro regime, Cuba also has been a top source of U.S. immigrants during the last half of the 20th century, consistently ranking among the top three Latin American source countries, and among the top ten worldwide.

The underpinnings of contemporary migration from Latin America also are rooted in policy changes designed to regulate permanent and temporary admissions, beginning with the Immigration Act of 1924. Although widely criticized for establishing a racist quota system designed to restrict migration from Southern and Eastern Europe, the 1924 Act is also relevant for contemporary Latin American immigration because it explicitly exempted from the quotas the independent countries Central and South America, including Mexico, and the Dominican Republic. Both countries currently are major sources of undocumented migration; however, the circumstances fostering each of these undocumented streams differ.

Table 1 summarizes key legislation that influences Latin American immigration today, beginning with the most recent comprehensive immigration law, the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1952 (INA). Although INA retained the quota system limiting immigration from Eastern Europe and that virtually precluded that from Asia and Africa, the legislation established the first preference system specifying skill criteria and imposed a worldwide ceiling. But in the wake of the Civil Rights Movement, the 1965 Amendments to INA dismantled the overtly racist quota system. Two aspects of the new visa preference system are key for understanding contemporary Latin American immigration, namely, the priority accorded to family unification relative to labor qualifications and the exemption of spouses, children and parents of U.S. citizens from the country caps, which in effect favored groups exempted by the 1924 Act. This included Mexican Americans whose ancestors became citizens by treaty and the relatives of braceros who had settled throughout the Southwest during the heyday of the guest worker program, but over time came to include the relatives of newcomers who sponsored their relatives after naturalization. The simultaneous termination of the Bracero program coupled with the extension of uniform country quotas for the Western hemisphere after in 1978 was particularly consequential for Mexico, with the predictable consequence that unauthorized migration climbed.

TABLE 1. Major U.S. Legislation Concerning Latin American Immigration: 1965 - 2001.

| Legislation | Date | Key Provisions |

|---|---|---|

| Immigration and Nationality Act (INA) | 1952 | Establishes the first preference system Retains national origins quotas favoring Western Europe Imposes ceiling of 154K plus 2K from Asia-Pacific Triangle |

| Immigration Act (Amendments to INA) |

1965 | Repeals national origin quotas Sets a maximum limit on immigration from the Western (120K) and Eastern Hemisphere (170K) Revises visa preference system to favor family reunification Establishes uniform per-country limit of 20,000 visas for the Eastern Hemisphere |

| Cuba Adjustment Act (CAA) | 1966 | Allows undocumented Cubans who have lived in the U.S. for at least one year to apply for permanent residence |

| Refugee Act | 1980 | Adopts UN protocol definition of refugee Creates systematic procedures for refugee admission Establishes resettlement procedures Eliminates refugees from the preference system Institutes the first asylum provision |

| Immigration Reform and Control Act (IRCA) |

1986 | Institutes employer sanctions for hiring undocumented immigrants Legalizes undocumented immigrants Increases border enforcement Establishes “wet foot/dry foot” policy |

| Cuban Migration Agreement (CMA) | 1994-1995 | Sets up a minimum of 20,000 visas annually Conducts in-country refugee processing |

| Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act (IIRIRA) |

1996 | Strengthens border enforcement and raises penalties for unauthorized entry and smuggling Expands criteria for exclusion and deportation Initiates the employment verification pilot programs |

| Nicaraguan Adjustment and Central American Relief Act (NACARA) |

1997 | Legalizes Nicaraguans and Cubans. It later legalizes ABC class members (Salvadorans and Guatemalans). |

| Temporary Protected Status (TPS) | Grants temporary legal status to nationals of countries that experienced an armed conflict or a major natural disaster. |

|

| 1990 | TPS granted to Salvadorans due to the civil war (lasted 18 months) |

|

| 1998 | TPS granted to Hondurans and Nicaraguans due to damages caused by Hurricane Mitch (expires 2013) |

|

| 2001 | TPS granted to Salvadorans following an earthquake (expires 2013) |

Sources: Fix and Passel 1994, Jasso and Rosenzweig 1990, Wasem 2009, 2011 and U.S. DHS website.

When an exodus from Cuba began in the aftermath of the Cuban Revolution, the United States had not established a comprehensive refugee policy. Although not a signatory to the UN Refugee Convention or Protocol and despite a highly unbalanced economic and political relationship with the United States, Cuba has influenced the development and execution of U.S. refugee policy in myriad ways. That Cuban émigrés instantiate the ideological war between the United States and Castro’s socialist regime not only forced the U.S. government to define its refugee policy, but also began a period of exceptions to official guidelines. The 1966 Cuban Adjustment Act (CAA) allows Cuban exiles to apply for permanent residence after residing in the United States for only one year. Unlike Haitians, Dominicans, or other Latin Americans, very few Cubans are repatriated if they land on U.S. soil, even if they enter through land borders.4

Cubans seeking asylum in the United States are the main Latin American beneficiaries of the 1980 Refugee Act, and they have enjoyed preferential admissions and generous resettlement assistance both before and since the 1980 Act.5 In response to a third major Cuban exodus during the mid-1990s, the U.S. government negotiated the Cuban Migration Agreement (CMA), which revised the CAA by establishing what became known as the “wet foot/dry foot” policy. By agreement, Cubans apprehended at sea (i.e., with “wet feet”) would be returned to Cuba (or a third country in cases of legitimate fears of persecution); those who successfully avoided the U.S. Coast Guard and landed on U.S. shores (i.e., with “dry feet”) would be allowed to remain and, in accordance with the provisions of the 1966 CAA, qualify for expedited legal permanent residence.6

A third major amendment to the INA, the 1986 Immigration Control and reform Act (IRCA), in principle mark a shift in the focus of U.S. immigration policy toward a growing emphasis on enforcement. IRCA granted legal status to approximately 2.7 million persons residing unlawfully in the United States, including the special agricultural workers who only were required to prove part year residence. Over 85 percent of the legalized population originated in Latin America, with about 70 percent from Mexico alone.7 Rapid growth of unauthorized immigration post-IRCA also intensified enforcement efforts. The 1996 Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act (IIRIRA), which intensified fortification of the border, expanded criteria for deportation, and made a half-hearted effort to strengthen interior enforcement through the employment verification pilot programs. More than a decade after IRCA Congress approved another legalization program, the Nicaraguan Adjustment and Central American Relief Act (NACARA), which conferred legal permanent resident status to registered asylees (and their dependents) from Nicaragua, Cuba, El Salvador, Guatemala and nationals of former Soviet bloc countries(and their dependents) who had resided in the United States for at least five consecutive years before December 1, 1995. According to Donald Kerwin, less than 70,000 asylees were legalized under NACARA through 2009, but in typical fashion a series of patch quilt solutions for specific groups have been enacted since IRCA.8

Finally, as part of its humanitarian goals, Congress also enacted legislation offering Temporary Protected Status (TPS) for Central Americans displaced by civil wars or natural disasters. TPS status is time limited; does not offer a pathway to permanent resident status; and requires acts of Congress for extensions.9 Once the period of protection expires, its beneficiaries are expected to return to their origin country. Among those displaced by civil conflict, some claim political asylum while others lapse into unauthorized status along with thousands denied asylum.

Collectively, the legislation summarized in Table 1 represents the major pathways to attain LPR status, namely family unification, employer sponsorship, and humanitarian protections. Family reunification gives preference to prospective migrants from countries with longer immigration traditions, like Mexico, because they are more likely to have citizen relatives in the United States who can serve as sponsors, but over time this pathway has become more prominent as earlier arrivals naturalize in order to sponsor their relatives. With the exception of Argentinians during the 1960s and Colombians during the early 1970s, relatively few Latin American immigrants receive LPR status through employment preferences. Rather, the majority of Latin Americans recruited for employment enter as temporary workers or through clandestine channels. Neither unauthorized entry or temporary protected status provides a direct pathway to LPR status, but both statuses can evolve into indirect pathways via comprehensive (e.g., IRCA) or targeted (e.g., NACARA) amnesty programs. In what follows we use the three pathways to illustrate how each differs for specific countries, and to identify the economic and political forces undergirding changes over time.

Recent Trends in Latin American Immigration

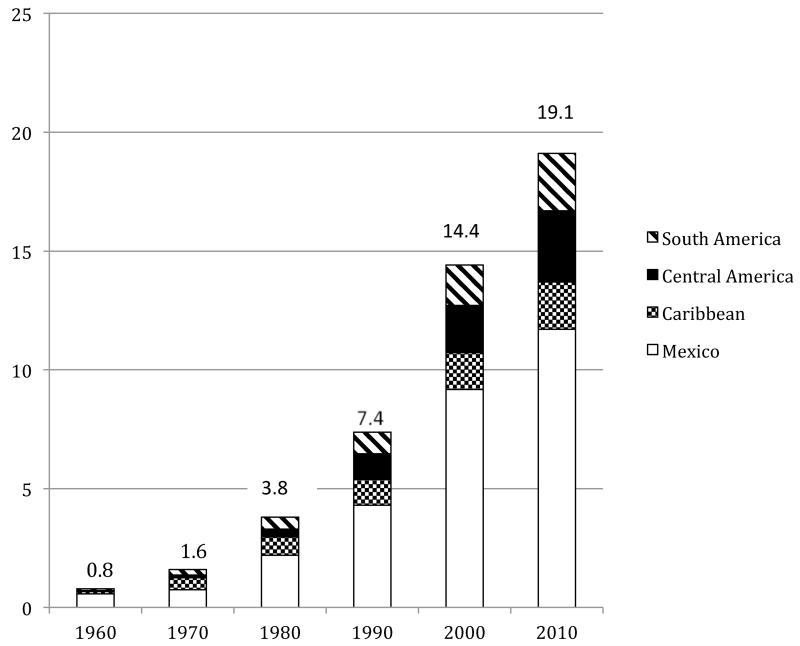

Figure 1 uses data from the decennial census to portray changes in the U.S. Latin American-born population from 1960 to 2010 by region of origin. The graphic representation reveals the regional origin diversification that accompanied the 12-fold increase in the Latin American-born population since 1970. Despite the continuing Mexican dominance among Latin American-born U.S. residents, flow diversification resulted in a more balanced sub-regional profile in 2010 compared with prior decades. The Caribbean share of Latin American immigrants peaked at 31 percent in 1970 but fell to 20 percent in 1980 and has remained at 10 percent since 2000. Over the last 50 years the Central American share of all Latin American immigrants rose from about six percent in 1960 to about 15-16 percent since 1990, when about 12 percent of Latin American immigrants originated from South America.

FIGURE 1. Foreign-Born Population from Latin America: 1960-2010 (millions).

“Caribbean” includes Cuba and the Dominican Republic; “Central America” includes Guatemala, Honduras, El Salvador, Nicaragua, Costa Rica, and Panama; and “South America” includes Colombia, Venezuela, Ecuador, Peru, Chile, Brazil, Bolivia, and Paraguay. Source: Campbell Gibson and Kay Jung, “Historical Census Statistics on the Foreign-Born Population of the United States: 1850–2000,” Population Division Working Paper No. 81 (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Census Bureau, 2006); and American Community Survey, One-Year Estimates for 2010.

Table 2 reports the major source countries that drove the changes reported in Figure 1. Only countries comprising at least two percent of the decade total Latin American-born population are separately reported, which qualifies a maximum of six countries after 1970 but only three in 1960. Not surprisingly, Mexicans remain the dominant group throughout the period, but owing to large swings in immigrant flows from the Caribbean and Central America, the Mexican share fluctuated from a high of 73 percent in 1960 to a low of 48 percent in 1970. Cubans were the second largest group among the Latin American-born population through 2000, but their share varied from a high of 27 percent in 1970 to less than 6 percent in 2010, when Salvadorans edged our Cubans for second place.

TABLE 2. Largest Latin American-Born Populations Residing in the United States by Country of Origin: 1960-2010.

(in percentages)

| 1960 | 1970 | 1980 | 1990 | 2000 | 2010 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Mexico (73.1) |

Mexico (47.6) |

Mexico (57.8) |

Mexico (58.2) |

Mexico (63.6) |

Mexico (61.3) |

|

|

Cuba (10.0) |

Cuba (27.5) |

Cuba (16.0) |

Cuba (10.0) |

Cuba (6.1) |

El Salvador (6.3) |

|

|

Argentina (2.1) |

Colombia (4.0) |

Dominican Republic (4.4) |

El Salvador (6.3) |

El Salvador (5.7) |

Cuba (5.8) |

|

|

Dominican Republic (3.8) |

Colombia (3.8) |

Dominican Republic (4.7) |

Dominican Republic (4.8) |

Dominican Republic (4.6) |

||

|

Argentina (2.8) |

El Salvador (2.5) |

Colombia (3.9) |

Colombia (3.5) |

Guatemala (4.3) |

||

|

Ecuador (2.3) |

Guatemala (3.1) |

Guatemala (3.3) |

Colombia (3.3) |

|||

|

Other Countries (14.8) |

Other Countries (14.3) |

Other Countries (13.2) |

Other Countries (13.8) |

Other Countries (13.0) |

Other Countries (14.4) |

|

| N | 788,068 | 1,597,481 | 3,801,351 | 7,385,479 | 14,418,576 | 19,115,077 |

Source: Gibson and Jung, 2006, Historical Census Statistics on the Foreign-Born Population of the United States: 1850-2000, and 2010 ACS 1-Year Estimates

The decade-specific profile of main source countries also reveals the ascendance of Colombians and Dominicans during the 1960s and 1970s, with Central Americans following during the 1980s. Although Argentina ranked among the top source countries during the 1960s and 1970s, when the United States benefitted from the exodus of its highly skilled professionals, the “brain drain” was not sustained. Political repression and economic crises rekindled Argentinian emigration during the late 1970s, and early 1980s and again at the beginning of the 21st century, but Spain, Italy and Israel are the preferred destinations. Today, unlike Colombia, Argentina is not currently a major contributor to U.S. immigration.

The stock measures reported in Table 2 and Figure 1 portray the cumulative impact of immigration, but reflect immigration trends imperfectly because they conflate three components of change: new additions; temporary residents, including the beneficiaries of protection from deportation; and unauthorized residents. Thus, the foreign-born population based on census data overstates the immigrant population, which consists of persons granted legal permanent residence (LPR) in any given period, including refugees and asylees. Therefore, to explain the ebb and flow of Latin American immigration over the last half century, we organize the remaining discussion around the three sources of immigrants: LPRs; refugees and asylees; and unauthorized migrants granted legal status.

Legal Permanent Residents

Table 3 reports the number of new LPRs from Latin America over the last five decades, with detail for the major sending countries from the Caribbean, Mesoamerica, and South America. Since the 1960s, Latin Americans comprised about one-third of new LPRs, with the period share fluctuating between 31 percent during the 1970s to 41 percent during the 1990s. For each period there is high correspondence between the dominant foreign-stock population countries (Table 2) and the number of new legal permanent residents admitted from those countries (Table 3); therefore, we use these nations to organize our discussion of specific streams.

TABLE 3. Latin Americans Granted Legal Permanent Residence Status: 1961-2010.

(in thousands)

| 1961-1970 | 1971-1980 | 1981-1990 | 1991-2000 | 2001-2010 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total (all countries) | 3,321.7 | 4,493.3 | 7,338.1 | 9,095.4 | 10,501.0 |

| Latin America (all countries) | 1,077.0 | 1,395.3 | 2,863.6 | 3,759.8 | 3,746.1 |

| Mexico | 443.3 | 637.2 | 1,653.2 | 2,251.4 | 1,693.2 |

| Caribbean | |||||

| Cuba | 256.8 | 276.8 | 159.3 | 180.9 | 318.4 |

| Dominican Republic | 94.1 | 148.0 | 251.8 | 340.9 | 329.1 |

| Central America | |||||

| El Salvador | 15.0 | 34.4 | 214.6 | 217.4 | 252.8 |

| Guatemala | 15.4 | 25.6 | 87.9 | 103.1 | 160.7 |

| Honduras | 15.4 | 17.2 | 49.5 | 66.8 | 65.4 |

| South America | |||||

| Colombia | 70.3 | 77.6 | 124.4 | 131.0 | 251.3 |

| Ecuador | 37.0 | 50.2 | 56.0 | 76.4 | 112.5 |

| Peru | 18.6 | 29.1 | 64.4 | 105.7 | 145.7 |

| Rest of Latin America | 111.1 | 99.2 | 202.5 | 286.2 | 417.0 |

Sources: Decades 1961-1970 and 1971-1980 from Statistical Abstract of the United States 1984. Decades 1981-1990, 1991-2000 and 2001-2010 from 1990, 1995, 2002 and 2010 Yearbook of Immigration Statistics.

Mexicans comprise the largest share of legal immigrants from Latin America, typically 40 to 45 percent per cohort except for the 1980s and 1990s, when the IRCA legalization was underway. The vast majority of Mexicans granted LPR status—88 percent in fiscal year 2010 for example—are sponsored by U.S. relatives; less than 10 percent qualified under the employment preferences.10 Mexicans comprised nearly 60 percent of all new LPRs from Latin America during the 1980s and 1990s, in part due to the large number of status adjusters under IRCA. Moreover, Mexican immigration would have been higher in each decade if the family-sponsored preferences were not numerically capped. Along with Filipinos, Chinese and Indians, Mexicans are greatly oversubscribed in the family sponsored preference categories and thus thousands of Mexican family members wait for years for their visa priority date. For example, in 2010 unmarried Mexican adult children sponsored by U.S. residents had waited 18 years for to receive their entry visa.11

Colombia, Ecuador and Peru are the major immigrant sending nations from South America. Although their initial levels of immigration differ, all three countries witnessed gradual increases during the 1970s, but thereafter their immigration flows diverged. Colombia was the largest single source of immigrants from South America throughout the period. Stimulated by prolonged political instability, armed conflict and drug violence amid sporadic economic downturns, Colombian emigration gained momentum over the latter half of the 20th century. The early waves largely involved upper class professionals with the resources to flee, but as the internal armed conflict escalated, members of the working classes joined the exodus.12 Legal immigration rose 60 percent between the 1970s and 1980s and nearly doubled after 2000.

Ecuadorian immigration trebled since 1961, rising from 37,000 during the 1960s to over 110,000 during the most recent decade. Demand for Panama hats produced in the provinces of Azuay and Cañar triggered the early waves of Ecuadoran immigrants during the late 1950s, but deteriorating economic conditions augmented subsequent flows from these regions, which were facilitated by dense social networks established by earlier waves.13 The collapse of oil prices in the 1980s combined with spiraling unemployment, wage erosion and inflation rekindled emigration, which averaged 17,000 annually. Following the collapse of the banking system in the late 1990s, emigration rose from approximately 30 thousand annually between 1990 and 1997 to over 100 thousand annually thereafter.14 However, Spain replaced the United States as a preferred destination during the 1990’s, hosting nearly half of all Ecuadorian emigrants between 1996 and 2001 compared with about 27 percent destined for the United States.15 Hyperinflation and massive underemployment resulting from the 1987 structural adjustment measures also accelerated Peruvian outmigration during the 1990s, more than doubling the number of new Peruvian LPRs, but the Peruvian share of the Latin American-born population never reached two percent. Except for the modest dip between the 1960s and 1970s, immigration from the rest of Latin America mirrors the Peruvian trend—doubling between the 1970s and 1980s and then continuing on an upward spiral that exceeded 400,000 since 2001 (Table 3).

Civil wars and political instability triggered the formidable influx of Salvadorians, Hondurans and Guatemalans to the United States. Emigration from El Salvador, the smallest but most densely populated of the Central American republics, is particularly noteworthy because of the sheer numbers that received LPR status—over 215,000 during the 1980s and an additional half million over the next two decades. That thousands of Salvadorians arrived seeking asylum largely explains why their LPR numbers exceed the annual caps for several decades. Hundreds of thousands lapsed into undocumented status when they were denied asylees status, but a large majority of Salvadorian asylees successfully adjusted to LPR status under NACARA.

Like El Salvador, Guatemala witnessed prolonged civil conflict, which escalated after 1978 and initiated a mass exodus of asylum seekers during the 1980s and 1990s. Those who arrived before 1982 qualified for status adjustment under IRCA but later arrivals did not. Although political instability is credited for the surge in Guatemalan immigration, Alvarado and Massey claim that neither violence nor economic factors predicted the likelihood of outmigration; rather, they portray Guatemalan emigration as a household decision to diversify income streams by sending young, skilled members to join U.S. relatives. Their interpretation is consistent with Hagan’s ethnographic account that chronicles how establishment of sister communities in U.S. cities enabled further migration via family unification.16 By 2010 Guatemala became the fourth largest Latin American-born group in the United States. The increase in Guatemalan legal resident admissions since 2001 also reflects the status adjustments authorized by NACARA.

By contrast to Guatemala and El Salvador, the rise in Honduran immigration has been more gradual, except for the 1980s, when it nearly trebled compared to the prior decade. Unlike Nicaraguans, Salvadorians and Guatemalans, Hondurans could not claim asylees status. Rather, skyrocketing poverty and unemployment during the 1980s and 1990s is responsible for the surge in emigration. In 1998 Hurricane Mitch aggravated the country’s economic woes, leaving hundreds of thousands homeless. An estimated 66,000 thousand Hondurans sought refuge in the United States and were granted temporary protected status (TPS), which does not confer a path to legal permanent residence. Unless renewed in 2013, Hondurans granted TPS will join the unauthorized population, which, according to the Office of Immigration Statistics, rose from 160,000 to 330,000 between 2000 and 2010.17 Currently family sponsorship is the main pathway to legal permanent residence for Hondurans, accounting for 85 percent of the recent LPRs.

The last major LPR flow since 1960 is from the Dominican Republic, which began in the wake of the political upheaval following dictator Trujillo’s assassination in 1961, but failed economic policies fueled the flow once the political scene stabilized. Since 1961 the number of new LPRs more than trebled, exceeding 330,000 during each of the last two decades. Despite modest economic growth during the 1990s and the revival of tourism, persisting high unemployment buttressed by deep social networks has maintained a steady exodus.18 Dominicans have been taking full advantage of the family unification provisions of the INA by sponsoring relatives; virtually all Dominicans granted LPR status in 2010 benefitted from the family sponsorship provisions of the INA.19

Refugees and Asylees

By definition, refugee and asylees flows precipitated by political upheavals and natural disasters are unpredictable both in timing and size, but how they impact immigrant admissions also depends on the idiosyncratic application of U.S. immigration and refugee policy. Since 1960 Cubans have dominated the refugee flow from Latin America, but armed conflicts in Central America and Colombia as well as natural disasters also contributed to the growth of humanitarian admissions in recent decades. The Cuban exodus has been highly unpredictable owing to barriers imposed by the Cuban government and the level of acrimony between Havana and Washington.

Cuban emigration began shortly after Fidel Castro assumed the reigns of the island nation. By 1974, 650,000Cubans left for the United States.20 Dubbed the Golden Exile because the vast majority of the first wave were professionals, entrepreneurs, and landowners, Cuban émigrés were granted visa waivers and parolee status, and were offered a range of services to facilitate their labor market integration, including certification of professional credentials, a college loan program, and bilingual education.21 Partly because they were fleeing a socialist state and partly because they did not fit the UN definitions of refugees, Cubans enjoyed a privileged position among the U.S. foreign-born population formalized by the 1966 Cuban Refugee Adjustment Act (CAA).. Importantly, CAA put Cubans on a fast track to citizenship.

A second major exodus occurred in April 1980, when the Cuban government opened the port of Mariel to anyone who wanted to leave, including prisoners and lunatics. About 125,000 thousand “Marielitos” arrived on U.S. shores in a few short months, and were joined by 35,000 thousand Haitians. 22 Although Marielitos did not formally qualify as refugees according to the guidelines of the newly enacted Refugee Act and were technically ineligible for federal funds, they were accorded refugee status by Congressional decree, illustrating yet again, the idiosyncratic application of U.S. immigration law. A third migration wave occurred in the mid-1990s when the Cuban government lifted the ban on departures. Rather than extend the welcome gangplank as in prior years, the U.S. government interdicted Cuban fugitives attempting to circumvent legal immigration channels and returned them to Guantanamo. Within a year, 33,000 Cubans were encamped at Guantanamo, but in yet another predictable exception to immigration law, the majority were paroled and granted LPR status.23 Although accompanied with less media fanfare than the 1980 Mariel boatlift, the largest number of Cubans to arrive in a single decade came after 2001; since that date nearly 320,000 thousand Cubans were granted LPR status. Under the provisions of the Wet Foot/Dry Foot agreement, Cubans interdicted at sea or apprehended on land are deportable, but in practice very few are returned because they are entitled to request asylum and most do so.

Central Americans and Colombians also have used the humanitarian pathway to acquire legal permanent residence, albeit with far less success than Cubans. Salvadorian and Guatemalan asylee approval rates were less than three percent between 1983 and 1990 compared with 25 percent for Nicaraguans.24 Alleging discrimination against Central Americans, religious organizations and immigrant rights advocates filed a class action lawsuit on their behalf, American Babtist Church v. Thurnburgh (ABC). As part of the 1991 settlement Congress allowed Central Americans denied asylum to reapply for review, and they achieved much higher success rates. However, the 1996 Illegal Immigrant Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act (IIRIRA) made the asylum rules even more difficult by adding provisions to resettle asylum seekers to third countries; by requiring asylees to file applications within a year arrival to the United States; by precluding appeals to denied applications; and by imposing high processing fees. After 1997 ABC class members were allowed to adjust their status through NACARA, where approval rates were over 95 percent.25

Two major natural disasters rekindled asylees from Central America at the turn of the 21st century, when Hurricane Mitch (1998) and a massive earthquake (2001) left over a million Salvadorans homeless. Drawn by a sizeable expatriate community in the United States, thousands of displaced Salvadorians made their way to the United States. In a humanitarian gesture, Congress granted Temporary Protected Status to Salvadorans residing in the United States as of 2001, and renewed the protection several times. As of 2010, over 300,000 Honduran (70K), Nicaraguan (3.5K), and Salvadoran (229K) citizens benefitted from temporary protected status (TPS).26 The status protections accorded to the victims of Hurricane Mitch and the Salvadoran earthquakes are set to expire in 2013. In the current political climate, it is uncertain whether their temporary protections will be extended; if they are not, many will probably join millions of others as undocumented residents.

Unauthorized migration

The growth of undocumented immigration since 1960 is not only a distinctive feature of the current wave of mass migration, but also a direct consequence of selective enforcement of U.S. immigration laws. As of March 2010 an estimated 11 million undocumented immigrants resided in the United States, down from a peak of nearly 12 million in 2007, but 29 percent higher than the 2000 estimate of 8.5 million.27 Latin Americans make up over three-fourths of undocumented residents, with 60 percent from Mexico alone. The collapse of the housing and construction industries during Great Recession fostered the first significant decline in the size of the undocumented population, reversing two decades of continuous growth. Removals from Latin America since 2001 more than quadrupled relative to the prior decade, which partly explains the shrinking unauthorized population, albeit less than changes in labor demand.

Several factors have fueled the growth of unauthorized migration from Latin America, beginning with the abrupt termination of the Bracero program in 1964, following a 22-year period during which U.S. growers became dependent on pliable Mexican labor. In some ways the 1965 Amendments constructed an illegal immigration system by default because the disproportionate focus on family visas gave short shrift to labor needs; because the Texas Proviso protected employers who willfully hired undocumented workers until IRCA imposed employer sanctions; and because the cap on family visas (except for immediate family members of U.S. citizens) produced long wait lists for countries with long immigration traditions. Furthermore, the integration of separate hemispheric ceilings into a single worldwide total in 1978 dramatically curtailed the number of visas available to Mexico, the largest single sending nation. As occurred when the Bracero program ended, unauthorized entry provided an alternative pathway to the United States, one greatly facilitated by the existence of strong social networks that were fortified over decades of relatively unrestricted migration.

Finally, decades of lax and inconsistent enforcement enabled millions of persons to enter without inspection, while shoddy monitoring of temporary visitors permitted hundreds of thousands of legal entrants to overstay their visa. Since 1986, however, U.S. immigration policy has been dominated by a growing emphasis on border enforcement, with heightened penalties for persons who enter without authorization as well as for nonimmigrants who remain in the country after their visas expire. Because IRCA’s employer sanctions provisions were never seriously enforced, unauthorized immigration rose during the 1990s, when the housing and construction industries—both dominated by unskilled workers—expanded. Weak interior enforcement basically left in place the lynchpin of unauthorized migration, namely employers’ ability to hire unauthorized foreign workers essentially without reprisal.

Even as IRCA’s comprehensive amnesty program was winding down, unauthorized migration was on the rise. In fact, during the 1990s, between 70 and 80 percent of all new migrants from Mexico were undocumented, and this share rose to 85 percent between 2000 and 2004.28 In a feeble attempt to reduce employment of unauthorized workers, the 1996 Illegal Immigrant Responsibility and Illegal Immigration Act (IIRIRA) authorized three pilot programs to verify employment eligibility, but protected employers from fines for declared good faith efforts to comply with verification requirements. Not surprisingly, IIRIRA did little to restrict the unauthorized flow from Latin America because interior enforcement remained weak; because the social networks sustaining the flows were already very deeply entrenched; and because the people smuggling networks and fraudulent document industries developed new avenues to circumvent the laws.

Future Challenges and Uncertainties

Migration is part of a multiphasic demographic response to unequally distributed social and economic opportunities that is simultaneously determined by micro and macro-level forces, many of which can not be predicted, such as sudden flows triggered by civil wars or natural disasters, or rigorously managed through policy measures, as demonstrated by the failure to seal the U.S.-Mexico border. Like most nations with long immigration traditions, the United States strives to balance economic, social and humanitarian goals through its admission preferences while also ensuring compliance with the laws. But an appraisal of Latin American immigration exposes numerous instances where extant laws have been systematically disregarded or applied in a capricious or discriminatory manner. Striking examples include the preferential treatment accorded to Cuban émigrés compared with Haitians who arrive on U.S. shores in similar situations; the explicit protection of employers who hire unauthorized workers by not holding them accountable for violating the law; and differential treatment of asylum applicants according to national origin. Fairness is not a defining feature of U.S. immigration policy toward Latin Americans.

Historically and now, Latin American immigration has afforded the United States myriad economic benefits, including lower prices for goods produced in industries that employ immigrant workers, increased demand for U.S. products, and higher wages and employment for domestic workers. That new immigrants accounted for half of the labor force growth during the 1990s added significantly to the economic prosperity enjoyed by average Americans. Nevertheless, it is doubtful that the current admission criteria that favor family unification over employment needs are well aligned with future economic needs of an aging nation. Suggestions to adjust employment visas with fluctuations in labor needs, while intuitively compelling, ignore that two-thirds of U.S. immigrants enter under family preferences and that the momentum for future flows is already baked in the system in the form of visa backlogs for Mexicans and others. Beyond immediate family relatives of U.S. citizens, however, it is worth reconsidering the social and economic value of maintaining the extended family preferences, which have become a key driver of Dominican and Salvadorian immigration in recent years.

Notwithstanding the visa backlogs for family sponsored relatives of Mexicans, there is some evidence that net migration from Mexico has slowed and may have even reversed.29 Bleak job prospects following the Great Recession are a key reason for the slowdown, but record high deportations under the Obama administration, a militarized border, and stepped up interior enforcement are contributing factors. Whether this slowdown in Mexican migration is a temporary blip or the beginning of a long-term reversal is yet unclear, and likely will depend both on the future pace of the U.S. recovery from the recession as well as the success of the Mexican government sustaining economic growth and dealing with its plague of drug-related violence. Lower fertility throughout Latin America also portends less surplus labor in the years to come.

Equally uncertain are the integration prospects of Latin American immigrants and their offspring, which is the looming issue for the future of the nation. The rise of anti-immigrant sentiment in response to an unprecedented geographic dispersal of Latin American immigrants highlights the formidable integration challenges facing the nation, which can thwart economic prospects in the years ahead while also fomenting ethnic conflict. Several worrisome trends warrant consideration. The recent Supreme Court decision upholding the states rights to empower local police to check the immigration status of anyone suspected of being in the country illegally bodes ill for the integration of Latin American immigrants, particularly those with indigenous roots who pose ready targets for racial profiling.

Another concern is the persisting achievement gap between the offspring of Latin American immigrants and their American-born counterparts. That births outpaced immigration as a component of Hispanic population growth after 2000 underscores the urgency of closing the education gap so that the children of Latin American immigrants can become productive replacement workers for the aging white majority. Recent trends are not encouraging, however. State and local governments have gouged education budgets in the interest of fiscal restraint, which not only reduces educational investments in future workers—large majorities of them children of immigrants—but also compromises the nation’s competitive advantages over the medium and long term.

Finally, the unresolved status of 11 million unauthorized immigrants, of which three-quarters are from Latin America—remains a thorny social, political, and moral issue. Legal status profoundly affects prospects for economic and social mobility. Kossoudji and Cobb-Clark estimated wage penalties for unauthorized status at 14 to 24 percent, and the benefit of legalization at six percent.30 This represents a formidable economic stimulus that can generate substantial multiplier effects via consumption. Our review of Latin American immigration reveals that thousands have benefitted from status adjustments through several group-specific Congressional acts. In the interest of transparency and uniformity in the application of immigration laws, a blanket amnesty will advance U.S. economic interests while advancing social cohesion. Another blanket amnesty will go a long way toward aligning our liberal democracy with the realities of Latin American immigration.

Contributor Information

Marta Tienda, Princeton University.

Susana Sanchez, Pennsylvania State University.

References

- 1.Gibson Campbell, Jung Kay. Historical Census Statistics on the Foreign-Born Population of the United States: 1850-2000. U. S. Census Bureau, Population Division; 2006. Working Paper No 81. The 2010 estimate is based on the Authors’ calculation from the American Community Survey.

- 2.Rumbaut Ruben D. The Hispanic prologue. In: Cardús D, editor. A Hispaniclook at the bicentennial. 1978. pp. 5–22. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wasem Ruth E. U.S. Immigration Policy on Permanent Admissions. 2010. CRS Report for Congress. RL32235, Figure 4. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wasem Ruth E. Cuban Migration to the United States: Policy and Trends. Congressional Research Service; Washington, D.C.: 2009. The difference between asylees and refugees is their physical location when requesting protection: asylees apply after arriving in the United States whereas refugees apply from abroad, often a third country, and request resettlement in the United States.

- 5.The current annual ceiling for refugee admissions is 80,000 per year, with 5,500 allocated for Latin American and the Caribbean. See Martin, Daniel C, Yankay James E. Refugees and Asylees: 2011. Department of Homeland Security, Office of Immigration Statistics; 2012. Annual Flow Report.

- 6.Furthermore, in an effort to discourage random surges in Cuban migration, the U.S. government set aside a minimum of 20,000 visas (excluding the immediate relatives of U.S. citizens) for Cubans seeking to immigrate, and instituted a “visa lottery” to allocate visas.

- 7.Tienda Marta, Borjas George J., Cordero-Guzman Hector, Neuman Kristin, Romero Manuela. The Demography of Legalization: Insights from Administrative Records of Legalized Aliens. University of Chicago; Sep, 1991. Final Report to the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation of the Department of Health and Human Services. Population Research Center Discussion Paper (OSC 91-4) [Google Scholar]

- 8.See Kerwin Donald M. More than IRCA: U.S. Legalization Programs and the Current Policy Debate. Migration Policy Institute Policy Brief; Washington D.C.: Dec, 2010. NACARA. Unlike IRCA, which was a comprehensive program, NACARA and other population-specific programs receive less media attention.

- 9.Wasem Ruth E., Karma Ester. Temporary Protected Status: Current Immigration Policy and Issues. Congressional Research Service; Washington, D.C.: 2010. CRS Report for Congress, RS20844. [Google Scholar]

- 10.U. S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS) Yearbook of Immigration Statistics: 2010. Department of Homeland Security, Office of Immigration Statistics; Washington, D.C.: 2011. Table 10. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wasem, 2010, op. cit., Table 4.

- 12.Murnan Alexandria. [accessed July 6, 2011];Colombian Immigrants. Encyclopedia of Immigration. 2011 Available from http://immigration-online.org/441-colombian-immigrants.html.

- 13.Jokisch Brad, Kyle David. Las transformaciones de la migración transnacional del Ecuador, 1993-2003. In: Herrera Gioconda, Carillo Maria Cristina, Torres Alicia., editors. La migración ecuatoriana transnacionalismo, redes e identidades. Plan Migración, Comunicación y Desarrollo; Quito, Ecuador: 2005. pp. 57–70. [Google Scholar]; Jokisch Brad. Migration Information Source [online magazine] Migration Policy Institute; Washington, DC: [accessed May 1 2012]. 2007. Ecuador: Diversity in Migration. Available from http://www.migrationinformation.org/feature/display.cfm?ID=575. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gallegos FranklinRamirez, Ramirez Jacques P. Estampida Migratoria: Crisis, Redes transnacionales y repertorios de acción migratoria. UNESCO, CUIDAD: Centro de Investigaciones; Quito, Ecuador: 2005. pp. 41–42. Eed, Abya Yala, Alisei. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gratton Brian. Ecuadorians in the United States and Spain: History, gender and niche formation. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies. 2007;33(4):581–599. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Alvarado Steven E., Massey Douglas S. Search of Peace: Structural Adjustment, Violence, and International Migration. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. 2010;630(1):137–161. doi: 10.1177/0002716210368107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Hagan Jacqueline M. Deciding to be legal: A Maya community in Houston. Temple University Press; Philadelphia: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hoefer Michael, Rytina Nancy, Baker Bryan C. Estimates of the Unauthorized Immigrant Population Residing in the United States: January 2010. U.S. Department of Homeland Security, Office of Immigration Statistics; Washington, D.C.: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hernández Ramona. The mobility of workers under advanced capitalism: Dominican migration to the United States. Columbia University Press; New York: 2002. [Google Scholar]; Peggy Levitt. Dominican Republic. In: Waters Mary C., Ueda Reed., editors. The New Americans: A Guide to Immigration since 1965. Harvard University Press; Cambridge, Massachusetts: 2007. pp. 399–411. [Google Scholar]

- 19.USDHS, 2011, op. cit., Table 10.

- 20.Portes Alejandro, Bach Robert L. Latin journey: Cuban and Mexican immigrants in the United States. University of California Press; Berkeley: 1985. [Google Scholar]; Rumbaut Ruben D., Rumbaut Ruben G. The family in exile: Cuban expatriates in the United States. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1976;133(4):395–399. doi: 10.1176/ajp.133.4.395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Portes and Bach, 1985, op. cit., p. 86

- 22.Perez Lisandro. Cuba. In: Waters Mary C., Ueda Reed., editors. The New Americans: A Guide to Immigration since 1965. Harvard University Press; Cambridge, Massachusetts: 2007. pp. 386–398. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wasem, 2009, op. cit; Perez, 2007, op.cit.

- 24.Mahler Sarah J. American dreaming: Immigrant life on the margins. Princeton University Press; Princeton, N.J.: 1995. p. 174. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Coutin Susan B. Falling Outside: Excavating the History of Central American Asylum Seekers. Law & Social Inquiry. 2011;36(3):585. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wasem and Ester, 2010, op cit.

- 27.Hoeffer, et al., 2011, op. cit. Table 3

- 28.Passel Jeffrey. [accessed July 10, 2012];Estimates of the Size and Characteristics of the Undocumented Population. 2005 Available from http://

- 29.Passel Jeffrey, Cohn D’Vera, Gonzalez-Barrera Ana. [accessed July 5, 2012];Net Migration from Mexico Falls to Zero—and Perhaps Less. 2012 Available from http://www.pewhispanic.org/2012/04/23/net-migration-from-mexico-falls-to-zero-and-perhaps-less/

- 30.Kossoudji Sherrie, Cobb-Clark Deborah A. Coming out of the Shadows: Learning about legal status and wages from the legalized population. Journal of Labor Economics. 2002;20(3):598–628. [Google Scholar]