Abstract

Background: Early palliative care provided through a palliative care consultative service is effective in enhancing patient outcomes. However, it is unknown whether the integration of palliative care as part of routine comprehensive cancer care improves patients' self-reported clinical outcomes.

Objective: The objective of this study was to evaluate the effects of a multidisciplinary coordinated intervention by advanced practice nurses at the clinic level on outcomes with patients newly diagnosed with late-stage cancer.

Methods: A clustered, randomized, controlled trial design was used. Four disease-specific multidisciplinary clinics were randomized to the 10-week intervention (gynecologic and lung clinics) or to enhanced usual care (head and neck and gastrointestinal clinics). Patient primary outcomes (symptoms, health distress, depression, functional status, self-reported health) were collected at baseline and one and three months, and secondary outcomes were collected one and three months postbaseline. General linear mixed model analyses with a covariance structure of within-subject correlation was used to examine the intervention's effect.

Results: The sample included 146 patients with newly diagnosed late-stage cancers. We found no differences between the two groups on the primary patient-reported outcomes at one and three months postbaseline; however, physical and emotional symptoms remained stable or significantly improved from baseline for both groups. Overall, secondary outcomes remained stable within the groups.

Conclusion: In this translational study, we demonstrated that if patients newly diagnosed with late-stage cancer were managed by disease-specific multidisciplinary teams who palliated their symptoms, providing whole-patient care, patient outcomes remained stable or improved.

Introduction

A diagnosis of cancer is a stressful, life-altering experience. Weisman and Worden1 described the first 100 days of this experience as an existential plight. When that diagnosis reveals late-stage disease, the patient and family are catapulted into chaos consumed with uncertainty associated with diagnostic tests coupled with a sense of urgency to make a decision to initiate treatment as soon as possible. Characteristics of late-stage cancer that require coordinated palliative care as a part of comprehensive cancer care include multiple physical needs, intense psychosocial distress, and complex patient and caregiver needs.2

The American Society of Clinical Oncology has recommended that there be full integration of palliative care as a routine part of comprehensive cancer care in the United States by 2020.3 We know that the integration of early palliative care by a palliative care team enhances patients' quality of life (QOL), including survival.4 What is not well known is whether integrated palliative care provided through disease-specific multidisciplinary teams will produce better patient outcomes. The challenge is to help disease-specific teams to provide early palliative care as a matter of course directly without having to rely solely on the consultation services of a palliative care team.

In light of this need, the investigators took their previously tested advanced practice nursing intervention5–9 and translated it into disease-specific clinics by members of the multidisciplinary team at a Northeastern cancer comprehensive center. The translation of the nursing intervention by different members of the team provided an opportunity to focus on care of the whole patient and not on which member of the team would deliver each component of the care the patient needed. To ensure the intervention was delivered as intended, the study advanced practice nurse (APN) met regularly with each team's clinic APNs, physician assistants (PAs), or medical social workers (MSWs) to review patients' status and management strategies. In this article we describe the methods and results of a clustered randomized trial evaluating the effects of a multidisciplinary intervention coordinated by APNs on patient-reported outcomes with newly diagnosed patients with late-stage cancers. We hypothesized that, compared with enhanced usual care, the intervention would be associated with stable or improved patient-reported outcomes.

Methods

A cluster randomization procedure was used to randomize four disease-specific clinics at Smilow Cancer Hospital (SCH) at Yale–New Haven into two groups: an intervention group (an APN-coordinated multidisciplinary intervention) and an enhanced usual care group (usual multidisciplinary care plus a copy of the symptom management toolkit with instructions on its use). Due to the ongoing interactions of the team members to discuss and share patients' treatment plans and management strategies in the disease-specific clinics, it was important to randomize the clinics and not the patients. Randomization was done using the ranuni function in conjunction with the rank procedure in statistical software SAS (SAS version 9.2 for Windows; SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). The head and neck and gastrointestinal clinics were randomized to the enhanced usual care and the gynecologic and lung clinics to the intervention group. SCH at Yale–New Haven is structured around 12 disease-specific oncology multidisciplinary clinics. Clinic teams include APNs, PAs, MSWs, nurse coordinators, medical oncologists, surgeons, and radiation oncologists.

Patient population

Eligible patients were identified at weekly tumor boards and qualified based on (1) a late-stage cancer diagnosis within 100 days; (2) postbiopsy or surgery with additional treatment recommended; (3) at least one self-reported chronic condition; and (4) age 21 years or older. Patients' oncologist asked patients if they were interested in the study. Research staff met with interested patients to explain the study, obtain consent, and administer baseline questionnaires.

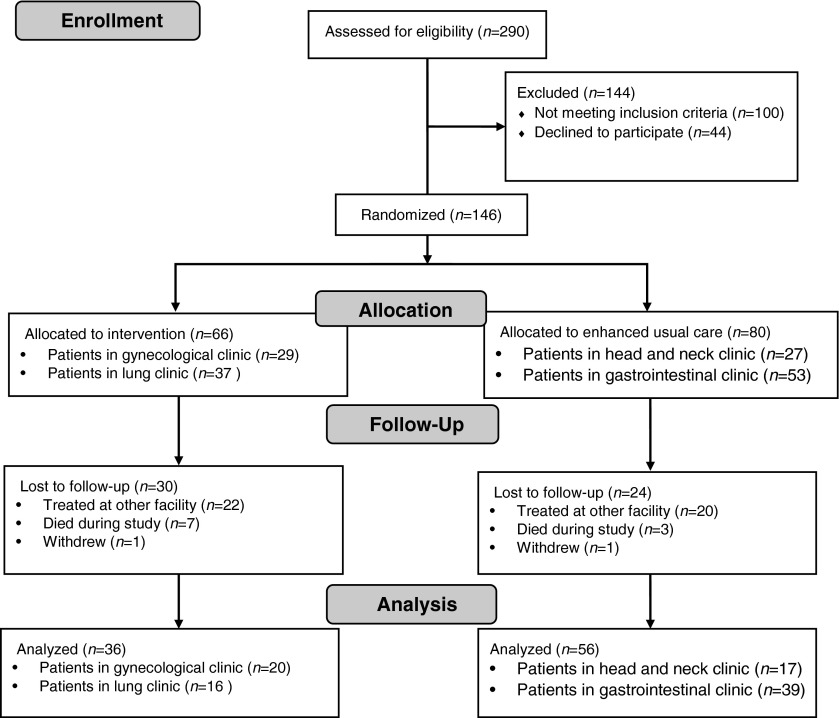

Two hundred and ninety patients were screened between August 2010 and December 2012. Of these, 146 participants were identified as eligible, agreed to enroll, and completed baseline data. Ninety-two patients completed the trial. See Fig. 1 for the CONSORT flow diagram.

FIG. 1.

CONSORT flow diagram.

The intervention

The essential components of the 10-week standardized intervention delivered by different members of each team included monitoring patients' status, providing symptom management, executing complex care procedures, teaching patients and family caregivers, clarifying the illness experience, coordinating care, responding to the family, enhancing QOL, and collaborating with other providers. In addition, goals of care were discussed. The study APN trained the clinic staff (APNs, PAs, MSWs) in the lung and gynecological clinics prior to the recruitment of patients. Clinic APNs initially contacted patients within 24 hours, and weekly phone and in-person contacts were scheduled (five clinic visits and five telephone calls). Members of each disease-specific multidisciplinary team worked together as a palliative care unit, each member taking on different functions to ensure all components of the intervention were addressed. The clinic APN oversaw the coordination and implementation of the intervention by different members of the team.

APNs, PAs, and MSWs in the two disease-specific clinics participated in three one-hour, one-on-one training sessions with the study APN coordinator. Training included review of evidence-based symptom protocols, documentation requirements, guidelines on handling adverse events and communication strategies to enhance patient problem solving, decision making, and self-efficacy.

Intervention fidelity was assessed and monitored by the study APN coordinator through quantification of whether the scheduled patient contacts occurred according to the protocol's timeframe and review of 10% of the documentation by the team members to ensure compliance with study protocols.

Enhanced usual care group

Patients in the enhanced usual care group did not receive the APN coordinated intervention but continued to receive routine oncology care delivered by multidisciplinary members of the head and neck and gastrointestinal disease-specific clinics. Both groups received a copy of the Symptom Management Toolkit, a resource manual describing 28 common symptoms and problems associated with cancer treatment and were instructed on its use.10

Data collection

Trained research assistants collected outcome data at three timepoints: within the first 100 days after diagnosis or recurrence (baseline) and one and three months after baseline. The Yale University School of Medicine Human Research Protection Program (institutional review board) approved the study.

Patient-reported measures

Standardized forms were used to obtain sociodemographic and clinical information, number of chronic comorbidities,11 and emotional distress.12 Standardized scales with strong psychometric properties were used to collect five primary patient outcomes at all three data collection points.

Symptom distress was measured by the Symptom Distress Scale (SDS), which contains 13 common cancer-specific symptoms. Distress is obtained as the unweighted sum of the 13 items, a value that could range from 13 to 65. Higher scores indicate greater distress.13

Health distress was measured by a four-item scale developed by the Stanford Patient Education Research Center. The scale is scored by the mean of the four items and ranges from 0 (none) to 5 (all of the time), higher scores indicating more distress.14

Depression was measured by the Personal Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9). The scale consists of nine items, scored from 0 to 3, with a range from 0 to 27. Higher scores reflect greater depression. If patients scored 2 or greater on item 9 (suicide), they were immediately referred for further evaluation.15,16

Functional status was measured by the Enforced Social Dependency Scale (ESDS), which consists of two components: personal and social competence. Personal competence includes six daily living activities; and social competence consists of home, work, recreational roles, and communication. Scores are summed to generate a personal score ranging from 6 to 36 and a social score ranging from 5 to 15, with higher scores reflecting greater dependency.17,18

Self-rated health was measured by the first item of the SF-12, which measures the physical and mental health aspects of health.19 The following four secondary outcomes were collected at one and three months postbaseline.

Quality of life was measured by the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-General (FACT-G) (version 4) and contains 27 items. The total FACT-G score ranges from 0 to 108, with higher scores reflecting better QOL.20

Anxiety was measured using the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS), 7 of the 14-item instrument designed to detect the presence and severity of anxiety (7 items). Scores of 0 to 7 in the anxiety subscale were considered normal, 8 to 10 borderline, and 11 or greater indicating clinical “caseness.”21

Uncertainty was measured by the Mishel Uncertainty in Illness Scale – Community Form (MUIS-C) and contains 23 items with a range of scores 23 to 115, higher scores indicating greater uncertainty.22

Self-efficacy was measured by the Self-Efficacy for Managing Chronic Disease Scale (SEMCD 6), a 6-item, 11-point numerical scale that measures the amount of confidence from 1, not confident at all to 10, totally confident.23

Internal reliability tests on the outcome measures used in this study revealed acceptable Cronbach's alphas ranging from 80% to 93%.

Analytic plan

Statistical analyses were performed with SAS. Means, standard deviations, and frequencies were used to describe the sample and outcomes. Longitudinal analyses were performed to examine the effects of the APN-coordinated intervention on primary and secondary outcomes at three months using the General Linear Mixed Model (GLMM) with a covariance structure of within-subject correlation.

The GLMM included a random intercept and a random slope to test time-group interaction after adjusting for age, gender, Emotional Distress Thermometer (EDT)-distress, and chronic condition. Few outliers were assessed using residual plot and Cook's distance, and the normality of residuals was visually checked using a quantile-quantile plot. Due to a significant violation of normality assumption, a log-transformed Enforced Social Dependency Scale (ESDS)-personal competence score was used in the model. Secondary outcomes were observed only at one month and three months. We estimated least square mean (LS-mean) at one and three months using GLMM adjusted for the covariates and compared LS-means between enhanced usual care and intervention at each timepoint. All tests were performed at 5% significance level and used a Bonferroni correction to avoid inflation of type I error from multiple comparisons.

Attrition analysis was performed to see potential bias from the dropouts. Greater number of dropouts were observed in lung cancer patients (56.8%) compared to those with head/neck (37.0%), gastrointestinal (26.4%), and gynecological (31.0%) cancer. None of the baseline outcome measures was associated with the dropouts at one month. However, greater symptom distress and health distress at one month were associated with more dropouts at three months in both enhanced usual care and intervention groups. To minimize bias from attrition, we used a continuous time variable with random slope in a longitudinal model. Then the prediction of missing outcomes at three months was estimated based on increase rates from baseline to one month.

Results

Patient characteristics in both groups were similar, except patients in the intervention group were older, had more chronic conditions, and were diagnosed with later-stage cancers (see Table 1). The mean age of patients was 60 years (range 27 to 87).

Table 1.

Sample Characteristics by Group Assignment at Baseline (N = 146)

| Characteristic | TOTAL (n = 146) | Enhanced usual care (n = 80) | Intervention (n = 66) | pa |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | ||||

| <65 years | 91 (62.3%) | 57 (71.3%) | 34 (51.5%) | 0.0152 |

| 65 years and older | 55 (37.7%) | 23 (28.7%) | 32 (48.5%) | |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 64 (43.8%) | 45 (56.3%) | 19 (28.8%) | 0.0011 |

| Female | 82 (56.2%) | 35 (43.7%) | 47 (71.2%) | |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||

| Caucasian/non-Hispanic | 124 (84.9%) | 66 (82.5%) | 58 (87.9%) | 0.3683 |

| Other | 22 (15.1%) | 14 (17.5%) | 8 (12.1%) | |

| Marital status | ||||

| Married | 82 (56.2%) | 42 (52.5%) | 40 (60.6%) | 0.3265 |

| Single/widowed/divorced | 64 (43.8%) | 38 (47.5%) | 26 (39.4%) | |

| Religious affiliation | ||||

| No | 22 (15.1%) | 16 (20.0%) | 6 (9.1%) | 0.0731 |

| Yes | 124 (84.9%) | 64 (80.0%) | 60 (90.9%) | |

| Education | ||||

| High school or less | 42 (28.8%) | 24 (30.0%) | 18 (27.3%) | 0.7172 |

| College or more | 104 (71.2%) | 56 (70.0%) | 48 (72.7%) | |

| Employment | ||||

| Full-/part-time working | 50 (34.2%) | 30 (37.5%) | 20 (30.3%) | 0.0870 |

| Retired | 46 (31.6%) | 19 (23.7%) | 27 (40.9%) | |

| Other | 50 (34.2%) | 31 (38.8%) | 19 (28.8%) | |

| Living condition | ||||

| Alone | 31 (21.2%) | 19 (23.7%) | 12 (18.2%) | 0.4140 |

| With others | 115 (78.8%) | 61 (76.3%) | 54 (81.8%) | |

| Time since diagnosis | ||||

| <3 months | 99 (67.8%) | 53 (66.3%) | 46 (69.7%) | 0.5997 |

| 3–12 months | 36 (24.7%) | 22 (27.5%) | 14 (21.2%) | |

| >12 months | 11 (7.5%) | 5 (6.2%) | 6 (9.1%) | |

| Comorbidity | ||||

| 0–2 | 75 (51.4%) | 51 (63.8%) | 24 (36.4%) | |

| 3–12 | 71 (48.6%) | 29 (36.2%) | 42 (63.6%) | 0.0012 |

| Treatment | ||||

| Surgery only | 15 (10.3%) | 15 (18.8%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Surgery and chemotherapy | 45 (30.8%) | 21 (26.3%) | 24 (36.4%) | |

| Surgery, chemo, & radiation | 10 (6.8%) | 5 (6,2%) | 5 (7.6%) | 0.2749 |

| Chemotherapy | 64 (43.9%) | 36 (45.0%) | 28 (42.4%) | |

| Chemo & radiation | 12 (8.2%) | 3 (3.7%) | 9 (13.6%) | |

P value indicates significance level comparing sample characteristics between intervention and enhanced usual care groups at baseline.

Primary outcomes at baseline, one and three months are reported in Table 2. The mean baseline values for symptom distress, emotional distress, and enforced social dependency (personal and social) were at or near the cut score levels: ≥24 for SDS, ≥4 for EDT, ≥12 for personal competence, and ≥7 for social competence. The coefficients of adjusted time effect (change over three months) and standard errors in each group are shown in Table 3. There was no significant difference in time effect between the groups after adjusting for the covariates. Both groups reported significant improvement on personal competence, and only the enhanced usual care group had significant improvement on social competence. Both groups also reported worse perceptions of their health over time.

Table 2.

Means and Standard Deviations of Primary Outcomes by Group at Baseline, One Month, and Three Months

| Baseline | One month | Three months | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total (n = 146) | Usual care (n = 80) | Intervention (n = 66) | Total (n = 122) | Usual care (n = 68) | Intervention (n = 54) | Total (n = 92) | Usual care (n = 56) | Intervention (n = 36) | |

| Outcome | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) |

| SDSa | 23.82 (7.18) | 23.63 (6.99) | 24.05 (7.45) | 23.53 (6.48) | 22.34 (5.90) | 25.04 (6.90) | 22.65 (7.54) | 22.80 (7.70) | 22.42 (7.40) |

| EDTa | 3.97 (2.77) | 3.84 (2.74) | 4.14 (2.82) | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Health distressa | 1.82 (1.27) | 1.78 (1.15) | 1.87 (1.40) | 1.59 (1.02) | 1.50 (0.93) | 1.69 (1.13) | 1.41 (1.14) | 1.40 (1.03) | 1.42 (1.30) |

| PHQ-9a | 5.10 (4.33) | 4.91 (4.06) | 5.33 (4.65) | 4.98 (4.26) | 4.31 (3.64) | 5.85 (4.85) | 4.64 (4.67) | 4.43 (4.03) | 4.97 (5.57) |

| ESDS personala | 12.66 (7.56) | 13.79 (8.73) | 11.30 (5.61) | 9.84 (5.25) | 9.56 (5.36) | 10.19 (5.13) | 9.22 (5.10) | 9.46 (5.33) | 8.83 (4.78) |

| ESDS sociala | 7.42 (3.18) | 7.69 (3.47) | 7.09 (2.77) | 6.21 (2.75) | 5.68 (2.80) | 6.89 (2.56) | 6.17 (2.67) | 6.05 (2.94) | 6.36 (2.21) |

| Self-rated healthb | 3.58 (1.11) | 3.61 (1.12) | 3.55 (1.11) | 3.23 (1.03) | 3.43 (0.95) | 2.98 (1.09) | 3.13 (1.08) | 3.16 (1.04) | 3.08 (1.16) |

aHigher score equals worse.

bHigher score equals better.

EDT, Emotional Distress Thermometer; ESDS, Enforced Social Dependency Scale; PHQ-9, Patient Health Questionnaire–Depression Scale; SDS, Symptom Distress Scale.

Table 3.

Interaction Effects between Time and Group on Primary Outcome over Three Months

| Time effect within groupa | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome | Enhanced usual care coefficient ± SE (p-value) | Intervention coefficient ± SE (p-value) | Time-group interactionp-value |

| SDSb | −0.887 ± 0.788 (0.2747) |

−0.235 ± 0.951 (0.8054) |

0.6108 |

| Health distressb | −0.321 ± 0.142 (0.0266) |

−0.312 ± 0.173 (0.0744) |

0.9698 |

| PHQ-9b | −0.213 ± 0.529 (0.6881) |

−0.135 ± 0.654 (0.8365) |

0.9268 |

| ESDS personalb (Log-transformed) | −0.276 ± 0.058 (<0.0001)* |

−0.197 ± 0.071 (0.0064)* |

0.3899 |

| ESDS socialb | −1.468 ± 0.366 (<0.0001)* |

−0.514 ± 0.446 (0.2504) |

0.1001 |

| Self-rated healthc | −0.455 ± 0.144 *** (0.0022) |

−0.590 ± 0.175 (0.0011)* |

0.5531 |

Statistically significant association on 5% type I error with p-values less than 0.0083 ( = 0.05/6; Bonferroni Correction).

Coefficients and SE of time effect (per three month) were estimated from GLMM with covariates including age, gender, EDT-distress, and chronic condition at baseline.

Higher score equals worst.

Higher score equals better.

EDT, Emotional Distress Thermometer; ESDS, Enforced Social Dependency Scale; GLMM, General Linear Mixed Model; PHQ-9, Patient Health Questionnaire–Depression Scale; SDS, Symptom Distress Scale; SE, standard error.

Secondary outcomes at baseline, one and three months are reported in Table 4. The mean values of these outcomes reflected a sample with mild anxiety, some uncertainty, and average well-being. These scores did not worsen between one and three months. In Table 5 the adjusted LS-means and standard errors were compared between the two groups at one and three months. Overall, secondary outcome scores remained stable within the groups. However, patients who received the enhanced usual care reported significantly better self-efficacy at one month (p < 0.0097) and less uncertainty at one month (p < 0.0007) and three months (p < 0.0106) compared to those in the intervention group.

Table 4.

Means and Standard Deviations of Secondary Outcomes at One Month and Three Months

| Three months (n = 92) | Three months (n = 92) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total (n = 122) | Enhanced usual care (n = 68) | Intervention (n = 54) | Total (n = 92) | Enhanced usual care (n = 56) | Intervention (n = 36) | |

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | |

| HADS-anxietya | 4.29 (3.86) | 3.90 (3.67) | 4.81 (4.07) | 3.90 (3.77) | 3.62 (3.61) | 4.33 (4.03) |

| Self-efficacyb | 7.30 (2.17) | 7.82 (1.78) | 6.64 (2.43) | 7.67 (2.12) | 7.84 (2.08) | 7.42 (2.19) |

| MUIS-Ca | 47.10 (13.89) | 43.81 (11.92) | 51.43 (15.18) | 46.30 (14.54) | 45.25 (12.92) | 47.94 (16.83) |

| FACT-Gb | 80.70 (16.98) | 82.91 (16.10) | 77.81 (17.80) | 82.45 (15.93) | 82.71 (14.47) | 82.07 (18.13) |

| PWB | 20.28 (5.65) | 21.09 (5.22) | 19.22 (6.05) | 20.89 (6.02) | 20.28 (6.40) | 21.83 (5.34) |

| SWB | 23.97 (4.59) | 24.01 (4.41) | 23.92 (4.87) | 23.97 (4.96) | 24.44 (5.07) | 23.26 (4.78) |

| EWB | 19.00 (4.60) | 19.57 (4.28) | 18.25 (4.93) | 19.04 (4.42) | 19.27 (3.35) | 18.70 (5.72) |

| FWB | 17.45 (6.77) | 18.24 (6.59) | 16.42 (6.92) | 18.55 (6.10) | 18.72 (5.96) | 18.28 (6.39) |

Higher score equals worse.

Higher score equals better.

EWB, emotional well-being; FACT-G, Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy–General (version 4); FWB, functional well-being; HADS, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale–anxiety; MUIS-C, Mishel Uncertainty in Illness Scale–Community Form; PWB, physical well-being; SWB, social/family well-being.

Table 5.

Least Square Means of Secondary Outcome at One Month and Three Monthsa

| Outcome | Time | Enhanced usual care LS mean ± SE | Intervention LS mean ± SE | Comparison between groups p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HADS-anxietyb | 1-month | 3.980 ± 0.429 | 4.654 ± 0.493 | 0.3258 |

| 3-month | 3.674 ± 0.453 | 4.846 ± 0.551 | 0.1173 | |

| Self-efficacyc | 1-month | 7.819 ± 0.257 | 6.610 ± 0.292 | 0.0097* |

| 3-month | 7.832 ± 0.273 | 6.830 ± 0.332 | 0.0275 | |

| MUIS-Cb | 1-month | 42.866 ± 1.688 | 52.321 ± 1.956 | 0.0007* |

| 3-month | 44.645 ± 1.803 | 52.441 ± 2.244 | 0.0106* | |

| FACT-Gc | 1-month | 82.828 ± 1.918 | 77.793 ± 2.242 | 0.1062 |

| 3-month | 81.342 ± 2.051 | 78.325 ± 2.493 | 0.3718 | |

| PWB | 1-month | 20.887 ± 0.689 | 19.227 ± 0.804 | 0.1126 |

| 3-month | 19.929 ± 0.750 | 20.986 ± 0.919 | 0.3932 | |

| SWB | 1-month | 24.093 ± 0.569 | 23.812 ± 0.658 | 0.7572 |

| 3-month | 24.782 ± 0.619 | 22.772 ± 0.750 | 0.0500 | |

| EWB | 1-month | 19.565 ± 0.536 | 18.379 ± 0.635 | 0.1761 |

| 3-month | 18.834 ± 0.565 | 18.266 ± 0.691 | 0.5435 | |

| FWB | 1-month | 18.159 ± 0.759 | 16.399 ± 0.886 | 0.1522 |

| 3-month | 18.415 ± 0.820 | 16.819 ± 1.001 | 0.2390 |

Statistically significant association on 5% type I error with p-values less than 0.0125 ( = 0.05/4; Bonferroni Correction).

LS-means and SE of secondary outcomes were estimated from GLMM with covariates including age, gender, EDT-distress, and chronic condition at baseline.

Higher score equals worst.

Higher score equals better.

EDT, Emotional Distress Thermometer; EWB, emotional well-being; FACT-G, Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy–General (version 4); FWB, functional well-being; GLMM, General Linear Mixed Model; HADS, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale–anxiety; LS-mean, least square mean; MUIS-C, Mishel Uncertainty in Illness Scale–Community Form; PWB, physical well-being; SE, standard error; SWB, social/family well-being.

Discussion

Patients' baseline outcome values reflected a symptomatic and physically compromised sample that warranted early palliative care and ongoing monitoring. We found no differences between the two groups on the primary patient-reported outcomes at one and three months postbaseline; however, physical and emotional symptoms remained stable or significantly improved from baseline for both groups. There was also a significant improvement in functional competence (activities of daily living) from baseline to three months in both groups; p < 0.0001 for the enhanced usual care and p < 0.0064 for the intervention group. The enhanced control group also had significantly less health distress at three months (p < 0.0266) and improved social functioning (p < 0.0001). We think these results are remarkable, in that given how sick these patients were, the results showed that forestalling symptom distress and improving functional status were clinically significant, with patients reporting that their symptoms had not gotten worse and their ability to care for themselves had improved.

Equally important, in our study, patients self-reported that their health decreased over time. We have observed this finding previously with patients with late-stage cancer: when patients' condition stabilizes and their symptoms do not worsen, patients assimilate a realistic understanding of their health status.24 This assimilation process occurs over time and reflects providers' willingness to be more frank with patients and open to dialoging about prognosis and treatment expectations. This increase in understanding for the current study was reflected in patients' report of less uncertainty. In addition, the staff APNs, PAs, and MSWs in both groups in this study were skilled at communicating with patients. They reported they helped patients to understand their disease and treatment, facilitated communication with members of the team and their family, and coordinated the use of outside resources.25

There have been other studies coordinated by nurses with late-stage patients with mixed results. Bakitas and colleagues achieved an improvement in QOL scores, but were unable to improve patients' symptoms between groups.26 Two other nurse-led intervention studies that included late-stage patients resulted in nonsignificant QOL outcomes; symptoms were not reported in either of these studies.27,28 A recent study by Schenkle's team29 demonstrated that palliative care management by specialty trained oncology nurses was feasible and acceptable to patients. Their intervention contained similar essential components to ours and showed promise as one approach of integrating early palliative care into comprehensive oncology care.

Zimmermann and colleagues30 designed a cluster randomized trial with late-stage patients to test the effects of early care by a palliative consultative team compared to standard care. They found no significant differences between groups at three months, but at four months a difference was noted.

One explanation for the result that patients' outcomes remained stable or improved in both groups may be related to the care provided by all members of the multidisciplinary teams in all four specialty clinics.31,32 This study coincided with the opening of a new hospital with a new cancer center director who held regular town hall meetings with the entire clinic staff to share his vision of the importance of personalized care delivered through coordinated disease-specific multidisciplinary teams. The director is the senior author on the landmark study demonstrating the impact of early palliative care on outcomes.3 The new infrastructure provided an opportunity for care to be organized in disease-specific clinics with multidisciplinary teams. It is well established that multidisciplinary team management improves patient survival and outcomes due to better staging and treatment plans.33 Over the last three decades, the team approach to management of cancer has evolved from tumor boards to sophisticated multidisciplinary management, which has become the standard of care in comprehensive cancer centers in the United States and globally. Chirgwin and colleagues34 surveyed multidisciplinary management teams (MDMs) to determine their contribution in care related to five domains: medical management, psychosocial care, palliative care, care in the community, and benefits to the team members. They reported that in addition to the medical management of care, MDMs provided palliative care focusing on symptom management and referrals in the areas of services available. Not unlike our intervention, they recognized the importance of continuity of care for patients and families to meet patients' needs throughout their cancer experience.

Limitations

We assumed our sample of late-stage patients across clinics was homogeneous, since they were all experiencing an existential crisis, symptom distress, and functional changes; but over time their experiences were quite different based on the treatment they received. Therefore, comparison of patient outcomes in only four disease-specific clinics was limiting. Bell and McKenzie recommend that a cluster design requires a greater number of clinics in order to limit intracorrelations, the degree of correlation in the outcome measures within each cluster.35

A noted strength of cluster analysis is avoiding contamination of patients by interventionists. However, patients enrolled in our sample were seen by providers who practiced in both groups. Inadvertently, both the APNs and medical oncologists in the lung clinic saw patients in the head and neck clinic to cover for vacations and staff turnover.

And finally the study was designed longitudinally, but we did not collect our full battery of outcome measures at baseline in order to minimize response burden. We intentionally limited the number of measures administered initially, but added them at one month and three months. This sacrifice in data collection prevented us from documenting baseline scores on our secondary outcomes. We also had a high degree of attrition over time. This tradeoff to recruit highly distressed patients who were newly diagnosed with late-stage cancer may have limited our ability to demonstrate statistically significant group differences over time.

Conclusions

In this translational study, we demonstrated that if patients newly diagnosed with late-stage cancer were managed by disease-specific multidisciplinary teams who palliated their symptoms with the aid of the symptom toolkit, patient outcomes remained stable or improved across the board. Care coordinated by APNs in multidisciplinary teams in disease-specific clinics facilitated management of the whole patient with late-stage cancer in order to stabilize conditions, monitor symptoms, gain a realistic grasp of their disease, maintain QOL, and potentially extend survival by intervening early with palliative care integrated with comprehensive cancer treatment. Additional research is needed to evaluate the integration of palliative care in disease-specific multidisciplinary clinics with patients with late-stage cancers with a larger cluster randomized design.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Drs. Frank Detterbeck, Ronald Salem, Peter Schwartz, Benjamin Judson, Hari Desphande, and Howard Hochster for patient referrals; Joseph Mendes, Irene Scanlon, and Donna Danbury for participating on teams; Drs. Mei Bai and Tony Ma for data management; and Marie Gallaher and Mary Ellen Clancy for data collection.

Author Disclosure Statement

Funded by NIH/NINR grant R01NR011872, McCorkle (PI).

References

- 1.Weisman AD, Worden JW: The existential plight in cancer: Significance of the first 100 days. Int J Psychiatry Med 1976;7:1–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tsai JS, Wu CH, Chiu TY, et al. : Symptom patterns of advanced cancer patients in a palliative care unit. Palliat Med 2006;20:617–622 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Temel JS, Greer JA, Muzikansy A, et al. : Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non-small cell lung cancer. N Eng J Med 2010;363:733–742 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ferris FD, Bruera E, Cherny N, et al. : Palliative cancer care a decade later: Accomplishments, the need, next steps—from the American society of Clinical Oncology. J Clin Oncol 2009:27:3052–3058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McCorkle R, Benoliel JQ, Donaldson G, et al. : A randomized clinical trial of home nursing care for lung cancer patients. Cancer 1989;64:1375–1382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McCorkle R, Jepson C, Yost L, et al. : The impact of post-hospital home care on patients with cancer. Res Nurs Health 1994;17:243–251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McCorkle R, Hughes L, Robinson L, et al. : Nursing interventions for newly diagnosed older cancer patients facing terminal illness. J Palliat Care 1998;14:39–45 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McCorkle R, Strumpf N, Nuamah I, et al. : A specialized home care intervention improves survival among older post-surgical cancer patients. J Am Geriatric Soc 2000;48:1707–1713 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McCorkle R, Dowd M, Ercolano E, et al. : Effects of a nursing intervention on quality life outcomes in post-surgical women with gynecological cancers. Psycho-Oncology 2009;18:62–70 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Given BA, Given CW, Espinosa C: Symptom Toolkit. Family Care Research Program, Michigan State University, 2003 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Berkman LF, Breslow L: Health and ways of living: The Alameda County Study. New York: Oxford University Press, 1983 [Google Scholar]

- 12.National Comprehensive Cancer Network: NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology: Distress Management, Version 1. 2011. www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/distress.pdf (last accessed August14, 2015)

- 13.Cooley ME, Short TH, Moriarty HJ: Symptom prevalence, distress, and change over time in adults receiving treatment for lung cancer. Psycho-Oncology 2003;12:694–708 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lorig R, Sobel DS, Stewart AL, et al. : Evidence suggesting that a chronic disease self-management program can improve health status while reducing hospitalization. Med Care 1999;37: 3–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL: The PHQ-9: A new depression and diagnostic severity measure. Psychiatric Ann 2002;32:509–521 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB: The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Inter Med 2001;16:606–613 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tang S, McCorkle R: A User's Manual for the Enforced Social Dependency Scale. New Haven, CT: Yale School of Nursing, 2002 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Richmond T, Tang ST, Tulman L, et al. : Measuring function. In: Frank-Stromborg M, Olsen SJ. (eds): Instruments for Clinical Health-Care Research, 3rd ed. Boston: Jones and Bartlett, 2004 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ware JE, Jr., Kosinski M, Keller SD: A 12-item short-form health survey: Construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med Care 1996;34:220–233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cella DF, Tulsky DS: Quality of life in cancer: Definition, purpose, and method of measurement. Cancer Invest 1993;11:327–336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Herrmann C: International experiences with the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale: A review of validation data and clinical results. J Psychosom Res 1997;42:17–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mishel M: Uncertainty in Illness Scales Manual. Chapel Hill, NC: The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 1997 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lorig KH, Ritter PL, Laurent DD, Fries JF: Long-term randomized controlled trials of tailored-print and small-group arthritis self-management interventions. Med Care 2004;42: 346–354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McCorkle R, Benoliel JQ: Symptom distress, current concerns, and mood disturbance after diagnosis of life-threatening disease. Soc Sci Med 1983;17:431–438 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tocchi C, McCorkle R, Knobf T, Ercolano E: Multidisciplinary specialty teams: Perceptions of care that influenced outcomes of patients with advanced cancer. J Adv Pract Oncol. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bakitas M, Lyons KD, Hegel MT, et al. : Effects of a palliative care intervention on clinical outcomes in patients with advanced cancer: The Project ENABLE II randomized control trial. JAMA 2009;302:741–749 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wagner E, Ludman E, Bowles E, et al. : Nurse navigators in early cancer care: A randomized, controlled trial. J Clin Oncol 2013;32:12–18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Uitdehang M, Van Putten P, Van Eijck C, et al. : Nurse-led follow-up at home vs. conventional medical outpatient clinic follow-up in patients with incurable upper gastrointestional cancer: A randomized study. J Pain Symptom Manage 2014;47:518–530 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schenker Y, White D, Rosenzweig M, et al. : Care management by oncology nurses to address palliative care needs: A pilot trial to assess feasibility, acceptability, and perceived effectiveness of the CONNECT Intervention. J Palliat Med 2015;18:232–240 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zimmermann C, Swami N, Krzyzanowska M, et al. : Early palliative care for patients with advanced cancer: A cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2014;383:1721–1730 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McCorkle R, Engelking C, Lazenby M, et al. : Perceptions of roles, practice patterns, and professional growth opportunities: Broadening the scope of advanced practice in oncology. Clin J Oncol Nurs 2012;16:382–387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McCorkle R, Knobf MT, Engelking C, et al. : Transition to a new oncology care deliver service: Opportunity for empowerment of the role of the advanced practice provider. J Adv Pract Oncol 2012;3:34–42 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Brar SS, Hong NL, Wright FC: Multidisciplinary cancer care: Does it improve outcomes? J Surg Oncol 2014;110:494–499 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chirgwin J, Craike M, Gray C, et al. : Does multidisciplinary care enhance the management of advanced breast cancer? Evaluation of advanced breast cancer multidisciplinary team meetings. J Oncol Pract 2010;6:294–300 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bell M, McKenzie J: Designing psycho-oncology randomized trials and cluster randomized trials: Variance components and intra-cluster correlation of commonly used psychosocial measures. Psycho-Oncology 2013;22:1738–1747 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]