Abstract

Techniques that can create three-dimensional (3D) structures to provide architectural support for cells have a significant impact in generating complex and hierarchically organized tissues/organs. In recent times, a number of technologies, including photopatterning, have been developed to create such intricate 3D structures. In this study, we describe an easy-to-implement photopatterning approach, involving a conventional fluorescent microscope and a simple photomask, to encapsulate cells within spatially defined 3D structures. We have demonstrated the ease and the versatility of this approach by creating simple to complex as well as multilayered structures. We have extended this photopatterning approach to incorporate and spatially organize multiple cell types, thereby establishing coculture systems. Such cost-effective and easy-to-use approaches can greatly advance tissue engineering strategies.

Introduction

The ability to encapsulate cells within biomaterials, like hydrogels, has been widely used to achieve three-dimensional (3D) culture of cells. Significant progress has been made over the years to engineer hydrogel matrices with tissue-specific mechanical and biochemical properties.1–7 Recent times have witnessed a surge of interest in recapitulating the heterogeneity and architectural complexity of native tissues in hydrogel scaffolds. To this end, a number of patterning and printing techniques have been developed.8–17 Some of these include nozzle-based printing, digital micromirror device (DMD) projection patterning, and laser-based stereolithography to create 3D structures, and methods to introduce required features into pre-existing 3D structures.8,12,14,18,19

Among the 3D patterning methods, the use of stereolithography-based approaches has garnered the most attention due to its versatility and ease of construction. In general, this method spatially restricts the exposure of light into a hydrogel precursor solution enriched with photoinitiators, thereby selectively polymerizing and creating patterned structures that can be controlled spatially. Methods, such as DMD projection printing, use computer-controlled micromirrors to selectively reflect light from a UV source to achieve spatially variant gelation of hydrogels.14,20 However, the simultaneous encapsulation of cells within DMD generated scaffolds is a difficult task. Laser-based methods have also been used, especially in applications where cells were incorporated into the scaffold in situ during the patterning process. In these approaches, a laser light source is directed and focused toward a precursor solution containing a mixture of cells, polymers containing acrylate groups, and photoinitiator placed on a motorized platform to initiate the gelation process. The programmed movement of the platform generates patterned architectures in the resulting hydrogel.19 In addition to these methods that require specialized technologies and equipment, studies have also employed easily accessible approaches such as pre-existing 3D structures and photomask-based systems to achieve similar results.8,11,13,15,21–29

In the case of photomask-based systems, a mask with desired patterns is printed onto a transparency such that light only penetrates regions that are not printed on with ink. A variety of approaches have been described using this method, including one where precursor polymer solution mixed with cells was infused into a mold, and polymerized with the mask acting as a selective barrier for UV light. This setup enabled multiple rounds of washing off nongelled regions, solution infusion, and subsequent polymerization to create 3D patterns. The changes in the photomasks at each step meant that different pattern designs can be added, where each new pattern incorporated both the depth of the previous and most recently polymerized pattern(s).13,23,29 This approach was used to create coculture systems where one cell type is encapsulated within patterned structures, while the second cell type is confined within the surrounding hydrogel.24 These mask-based methods were further diversified through efforts using hydrogel polymerization that is inversely dependent on UV intensity exposures based on the degree of transparency on photomask. Thus patterned porosity within the hydrogel could be generated.25 Using the overall photomask approach, a visible light-based photopolymerization of multiple layers with different designs using lasers was also achieved with added benefits of chemical tethering of different layers.26

The merging of 3D patterning with stem cells and biomaterials has undeniably provided researchers new prodigious tools to create complex tissues. The widespread application of such approaches, however, relies on easily adaptable and easy-to-devise protocols. To this end, we have integrated a photomask-based stereolithography approach coupled with the photopolymerization of precursors to create patterned 3D structures reinforced with a surrounding hydrogel layer. As a proof-of-concept, we have created a wide variety of mechanically robust micro- and macroscale structures with simple to complex architectures. We have also demonstrated their use in cell culture.

Materials and Methods

Synthesis and purification of gelatin methacrylate

Gelatin methacrylate (GelMA) was synthesized as described previously.30 In short, 10 g of bovine skin type B gelatin (Sigma-Aldrich) was added to 100 mL phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; Gibco) to obtain a 10% (wt/v) solution and stirred at 60°C for a minimum of 30 min to achieve complete dissolution. Around, 8 mL of methacrylic anhydride (Sigma-Aldrich) was added dropwise to the gelatin solution at a rate of 0.5 mL/min. This continuously stirred solution was brought to 50°C, reacted for 1 h, and quenched by the addition of a 2×dilution of warm PBS. This was dialyzed against Milli-Q water using a dialysis tubing with a 12–14 kDa cutoff (Spectrum Laboratories) for 1 week (three times/day water change) at 40°C to remove the excess reactants. The GelMA solution was filtered, frozen down, and lyophilized for 4 days. Before cellular encapsulation, the dried GelMA was further purified using a Sephadex G-25 column (GE Healthcare Life Sciences) and relyophilized.

Synthesis and purification of poly(ethylene glycol)-diacrylate

Poly(ethylene glycol)-diacrylate (PEGDA) was prepared as previously described.31 Briefly, 5.29 mmol of poly(ethylene glycol) (18 g of 3.4 kDa; Sigma-Aldrich) was dissolved in 300 mL of toluene at 127°C and kept under reflux for 4 h with vigorous stirring. To remove trace amounts of water, the solution was subjected to azeotropic distillation. One hundred eighty milliliters of anhydrous dichloromethane was added at room temperature, and subsequently, 1.623 mL (11.64 mmol, 2.2 equivalents) of triethylamine was added under vigorous stirring. The reaction mixture was transferred to an ice bath to further cool it down. Upon cooling, 0.942 mL (11.64 mmol, 2.2 equivalents) of acryloyl chloride mixed in 15 mL of anhydrous dichloromethane was introduced dropwise to the mixture at 4°C over 30 min. The reaction was kept for 30 more minutes at 4°C before increasing to 45°C overnight. The reaction mixture was filtered through diatomaceous earth to remove quaternary ammonium salts. The filtrate was concentrated using a rotary evaporator and precipitated in excess diethyl ether. The precipitated product was redissolved in dichloromethane and reprecipitated in diethyl ether. The resultant PEGDA was filtered and dried under vacuum at room temperature for 24 h. The dried PEGDA was further purified using a Sephadex G-25 column (GE Healthcare Life Sciences) and lyophilized.

Synthesis of lithium phenyl-2,4,6-trimethylbenoylphosphinate

Lithium phenyl-2,4,6-trimethylbenoylphosphinate (LAP) was prepared as previously described.32 The 2,4,6-trimethylbenzoyl chloride (Alfa Aesar) was introduced dropwise to an equal molar of dimethyl phenylphosphonite (Alfa Aesar) while stirring at room temperature under argon. After 18 h, the temperature of the reaction mixture was increased to 50°C. Lithium bromide, mixed in 2-butanone, was added in excess, resulting in precipitation within 10 min. Upon precipitation, the temperature was once again cooled to room temperature for another 4 h. The precipitate was collected through filtration, and washed thrice using 2-butanone to ensure complete removal of excess lithium bromide. The product was dried under vacuum to remove excess 2-butanone, to yield LAP.

Methacrylation of glass coverslips

The glass surface was methacrylated according to the manufacturer's protocol. Briefly, 15 mm diameter glass coverslips were treated with 2.5 M NaOH solution for 30 min before rinsing in DI water, and dried under airflow. A dilute solution of glacial acetic acid was prepared in deionized (DI) water at a ratio of 1:10. A working solution containing 200 μL of ethanol, 1 μL of 3-(trimethoxysilyl) propylmethacrylate (Sigma-Aldrich), and 6 μL of the diluted acetic acid was prepared. The cleaned glass surfaces were treated with this working solution for 6–10 min before rinsing with pure ethanol for 10 min. The coverslips were dried under airflow and incubated in 60°C for 2 h. The coverslips were used within 24 h.

Poly-L-lysine poly(ethyleneglycol)-coated coverslips

Twelve or 15 mm diameter coverslips, or 22×22 mm square coverslips were treated with 100% ethanol for 15 min and dried under gentle airflow. The cleaned glass surfaces were exposed to UV/ozone for 6 min and were immediately treated with 0.1 mg/mL poly-L-lysine poly(ethylene glycol) (PLL-PEG) (Surface Solutions), diluted in PBS from a stock solution with a concentration of 5 mg/mL. After 30 min of PLL-PEG treatment, the coverslips were rinsed in DI water and were dried through aspiration. PLL-PEG-coated coverslips were used within 24 h.

3D patterning of structures

The designs of interest were generated using the software AutoCAD. The file was then sent to CAD/Art Services, Inc., who generated the corresponding transparency photomask. The photomask along with a collimated light was used to selectively polymerize the desired structures. Specifically, the photomask was placed directly on the stage of an inverted microscope. A photopolymerizable solution (here GelMA with LAP), which was sandwiched between two coverslips, was placed directly on the photomask and polymerized with collimated UV light (Supplementary Fig. S1; Supplementary Data are available online at www.liebertpub.com/tec).

Embedded 3D patterning

A known weight of GelMA powder was added into a known volume of PBS to create 10% wt/v solution. The GelMA in PBS solution was vortexed at room temperature to dissolve the polymer. The resultant mixture was transferred to a 60°C water bath for 15 min and vortexed for an additional minute at room temperature. This process was repeated once more to achieve complete dissolution of the GelMA in PBS. Once completely dissolved, the solution was brought to 37°C and used to create acellular and cell-laden hydrogel structures.

The 10% wt/v GelMA solution was supplemented with the photoinitiator LAP and 200 nm diameter green fluorescent particles at concentrations of 2 mM and 1% v/v, respectively. A 22×22 mm square coverslip was cleaned in DI water and dried before adding the precursor solution onto the surface. A PLL-PEG-treated 12 mm coverslip was gently placed on top to sandwich the solution between the two glass surfaces.

A transparency photomask containing dark background and clear patterns was placed onto the microscope stage and positioned under bright-field such that the desired pattern is centered over the eyepiece. The GelMA solution between the coverslips was placed onto the mask and photopolymerized using a collimated UV light source, which was generated by passing the light from an X-Cite Mercury lamp through a conventional DAPI channel filter cube with excitation and emission centered around 358 and 463 nm, respectively. The gelled construct was transferred to a Petri dish filled with 37°C PBS and the solution was pipetted gently yet repeatedly between the glass coverslips to remove the unpolymerized GelMA solution and detach the PLL-PEG-treated coverslip. The resulting GelMA structures were temporarily stored within a PBS solution.

PEGDA (Mn: 3400) was dissolved in PBS to achieve 10% wt/v along with 2 mM LAP and 1% wt/v of 200 nm diameter red fluorescent particles. The GelMA structures attached to the square coverslips were retrieved and the excess liquid was aspirated before the addition of the PEGDA precursor solution onto the GelMA patterns. A 15 mm diameter methacrylated coverslip was gently placed on top and was polymerized as previously described. The coverslip was transferred into a PBS solution afterward and the gelled construct tethered onto a methacrylated coverslip was retrieved. The hydrogel composite structure, with GelMA and PEGDA, was stored within a PBS solution.

To complete the enclosure of the GelMA features within the PEGDA hydrogel, PEGDA precursor solution was aliquoted onto a 22×22 mm square coverslip. The patterned construct was retrieved and the excess liquid was removed before placing the hydrogel surface onto the precursor solution. After photopolymerization and removal of the coverslip, the supported 3D constructs tethered onto 15 mm diameter coverslips were obtained.

Free-standing photopatterned scaffolds

The GelMA patterns were constructed on 22×22 mm square coverslips and were incubated in PBS as described in Embedded 3D Patterning. PEGDA was dissolved in PBS to obtain a solution containing 10%, 20%, or 30% wt/v along with LAP (concentration of 2 mM). The coverslips containing the patterns were removed from PBS and the excess liquid was aspirated. The PEGDA solution was added onto the patterns and a 15 mm diameter PLL-PEG-coated coverslip was placed on top. The precursor solution was photopolymerized and the resulting gel was incubated in PBS for 5 min at room temperature. The PLL-PEG-coated coverslip was mechanically removed. The GelMA construct remaining on the square coverslip was carefully detached to yield a free-standing scaffold.

Multilayered scaffolds

The methodology resembles the procedure discussed in Embedded 3D Patterning, however, with significant modifications. To create the first layer of the scaffold, 22×22 mm square coverslips were coated with PLL-PEG while the 15 mm diameter circular coverslips were methacrylated. This resulted in GelMA structures covalently bonded to the circular coverslip. GelMA precursor solution supplemented with 2 mM LAP was added onto the PLL-PEG-coated square coverslip before placing the circular coverslip onto the solution submerging the GelMA structures. The construct was photopolymerized and the circular coverslip was removed. The above process was repeated to construct supporting layers and additional patterned layers.

Cell culture and encapsulation

Human mesenchymal stem cells (hMSCs), human fibroblasts, and MDA-MB 231s (breast cancer cell line) were cultured in a growth medium comprised of 1% penicillin/streptomycin, 1% l-Glutamine, 10% fetal bovine serum (Gibco), and 88% Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM, HyClone®; Thermo Scientific). Human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) were cultured in a medium (HUVEC medium) composed of 1% sodium pyruvate (Life Technologies), 1% penicillin/streptomycin, 10% fetal bovine serum (Gibco), 10% endothelial cell growth medium (Gibco), and 78% M199 (Gibco).

To label the cells, they were trypsinized and resuspended in 7 μM green or red CellTracker dyes (Molecular Probes®; Life Technologies) or 1 μg/mL of Hoescht 33342 (Life Technologies) dissolved in Opti-MEM (Gibco). After 20 min of incubation, the cells were washed multiple times with PBS.

During the cell encapsulation, a cell pellet, containing between 2 and 6 million cells, was resuspended in 100 μL of 10% GelMA precursor solution supplemented with 2 mM LAP and 0.01% ascorbic acid. The cells were patterned following the procedure discussed in Free-standing photopatterned scaffolds until the step where cell-laden GelMA patterns were embedded with an additional hydrogel layer. Here, the construct was not detached from the glass. Although we use both GelMA and PEGDA to create the surrounding hydrogel layer, in the ones shown in Figure 4, the hydrogel layer used was GelMA. The cell-laden constructs were incubated in sterile PBS containing 2% penicillin/streptomycin for 5 min at 37°C before replacing the solution with growth medium. The cocultures involving HUVEC cells were cultured in HUVEC medium.

FIG. 4.

Encapsulation of cells. (A, B) 3D reconstruction of cells within the patterned hydrogel and the surrounding GelMA hydrogel layer (Left column), where the cells were fluorescently labeled with green cell tracker. (Right column) Phase-contrast and live/dead images of the cylindrical patterns, and live/dead images of distinct layers of the bilayer structures. In live/dead images the green cells indicate viable cells, while the red indicates nonviable cells. Scale bar for (A): 200 μm. Scale bar for (B): 150 μm. (C) Cocultures of human umbilical vein endothelial cell (HUVEC) and MDA-MB-231 cells, where the MDA-MB-231 cell-laden GelMA cylindrical structures are surrounded by hydrogels containing HUVECs. Phase-contrast image (top) along with corresponding live/dead image (bottom). Scale bar: 200 μm. (D) Phase contrast and the fluorescently labeled fibroblasts and HUVECs (bottom) spatially patterned within cylindrical GelMA structures. For easy visualization, the cells were labeled with dyes, with HUVECs represented as red and fibroblasts represented as green. Scale bar: 200 μm. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/tec

Live/Dead Assay of cellular constructs

The cell-encapsulated constructs were first washed three times with PBS, and subsequently incubated in a live/dead solution (500 μL DMEM containing 0.25 μL of calcein AM, 1 μL of ethidium homodimer-1; Life Technologies) for about 30 min at 37°C. After incubation, the constructs were once again washed thoroughly with PBS to remove residual dye, and imaged using fluorescence microscopy.

Results

Scaffold fabrication

GelMA solution of 10% wt/v was used for the fabrication of 3D-patterned hydrogel structures of varying shape, size, height, and complexity. The formation and optimization of the structures were carried out using fluorescent particles of 200 nm diameters suspended in GelMA solution allowing easy visualization of the resulting structures. Furthermore, we tested the cytocompatibility of the described fabrication procedure for various cell types (hMSC, human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs), human fibroblasts, MDA-MB 231). Both homogeneous and coculture systems were implemented.

Embedded 3D patterning

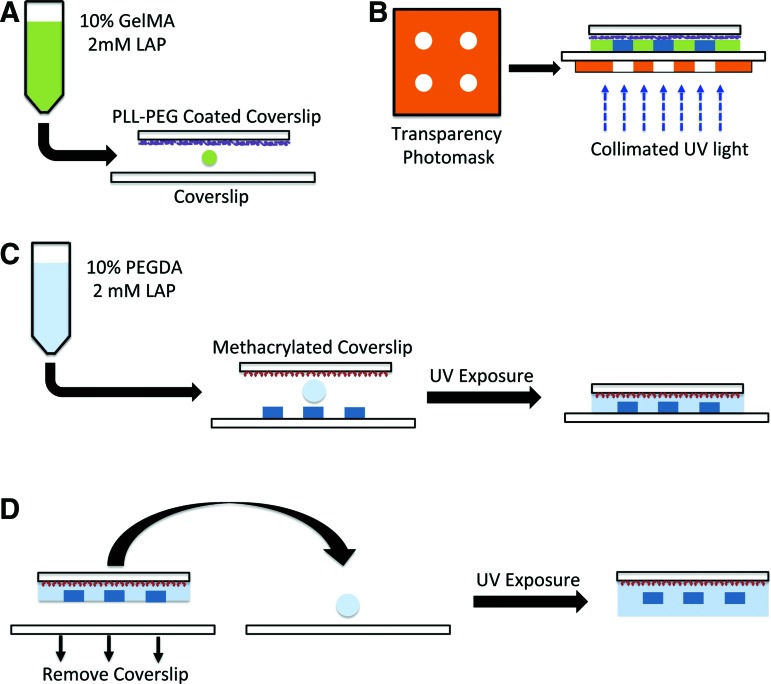

The GelMA solutions supplemented with LAP and fluorescent particles were sandwiched between PLL-PEG-treated and regular coverslips (Fig. 1A), which were exposed to a collimated UV light through a photomask printed with the desired patterns. The PLL-PEG treatment was used to promote adhesion of the hydrogel onto the regular coverslip. The nonirradiated regions were then washed off to leave behind the 3D patterned GelMA structures (Fig. 1B). To embed the 3D patterned structures within a hydrogel, the GelMA structures formed onto the glass coverslip was immersed within PEGDA precursor solution and photopolymerized, where the PEGDA solution was sandwiched between the GelMA layer and a methacrylated glass coverslip before gelation (Fig. 1C). The use of methacrylated coverslip ensures the detachment of the GelMA structures after they are embedded within the PEGDA hydrogels. To achieve the complete embedment of the GelMA structures, the above-mentioned procedure was repeated using a glass coverslip that was not methacrylated (Fig. 1D). Although the results describe the use of PEGDA to create the surrounding layer, any photopolymerizable biomaterial could be used. We have validated the use of PEGDA and GelMA toward this patterning approach.

FIG. 1.

Schematic representation of the protocol for generating three-dimensional (3D) patterned structures. (A) The gelatin methacrylate (GelMA) solution was sandwiched between a poly-L-lysine poly(ethylene glycol)-coated coverslip and a nontreated coverslip. (B) The sandwich was exposed to collimated UV light with a transparency photomask to selectively block the light reaching the GelMA solution. (C) Precursor solution, consisting of poly(ethylene glycol)-diacrylate (PEGDA), was added onto the patterned structures and sandwiched with a methacrylated coverslip before exposing to UV. (D) To completely embed the patterned GelMA structures, PEGDA solution was sandwiched between a coverslip and the previous structure from (C) and exposed to UV. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/tec

Varying the height and size of the 3D patterned structures

The photopatterning process described in this study can be used easily to vary the height and sizes of the patterned structures. The height of the structures can be easily adjusted by varying the volume of GelMA precursor solution sandwiched between the coverslips. By photopolymerizing volumes of 8, 14, and 20 μL of GelMA solutions, we fabricated cylindrical structures with heights of ∼47, 103, and 115 μm, respectively (Fig. 2A). Figure 2A depicts the z-stack confocal images of the cylindrical hydrogel structures of different heights. The X-Y cross-sections show the circular GelMA structures, embedded with green fluorescent beads, surrounded by PEGDA hydrogels embedded with red fluorescent beads (Fig. 2A, top panel). The confocal images in X-Z plane show the increase in height of the GelMA structures encased within the PEGDA layer with increase in the volume of the GelMA precursor solution (Fig. 2A, bottom panels). The images of GelMA with green beads and PEGDA with red beads have been merged to demonstrate the embedment of GelMA structures within a PEGDA hydrogel. The size of the structures can be controlled by altering the size of the patterns on the photomasks. Figure 2B illustrates X-Y cross-sections of the circular structures with increasing diameters of ∼80, 160, and 250 μm. In addition to circles, we have also created other basic geometries such as triangles and squares. The 3D reconstructed images from the z-stack volumes of these structures are depicted in Figure 2C. Since the 3D structures are mechanically supported by the PEGDA hydrogels, we can generate free-standing scaffolds containing embedded 3D patterned GelMA structures. The mechanical properties of the PEGDA hydrogels increase with increasing precursor concentration.33 By tuning the concentration of the PEGDA hydrogels from 10% to 30%, we can vary the mechanical properties of the hydrogel surrounding the GelMA structures (Fig. 2D).

FIG. 2.

Optimization and characterization of patterned structures. (A) The height of the patterned features was adjusted by changing the volume of the GelMA solution from 8 to 20 μL before gelation. Horizontal scale bar: 100 μm. Vertical scale bar: 50 μm. (B) Cylindrical patterns with increasing diameters of 80, 160, and 250 μm were generated by altering the design on the photomask. Scale bar: 75 μm. (C) 3D reconstruction of the GelMA structures with different extruded shapes—circular, triangle, and square. (D) Free-standing patterned GelMA structures surrounded with a PEGDA hydrogel with varying PEGDA concentration (30–10%). The inset shows the GelMA patterns within the PEGDA hydrogel, with the arrow provided for easy identification. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/tec

Generating complex and multilayered structures

We have extended the photopatterning process to create large, complex structures. To this end, we employed image processing techniques on available images of Isaac Newton to generate a binary image suitable for the photomask. Employing this photomask and following the protocol described in Materials and Methods, we have created a 3D patterned portrait of Isaac Newton in GelMA structures embedded within the PEGDA hydrogels (Fig. 3A). We employed a similar approach to recreate, in hydrogel form, the vascular network observed in the kidney based on a figure from Marxen et al.34 Figure 3B shows the X-Y cross-section depicting the vascular network structure made of GelMA with the surrounding PEGDA structures.

FIG. 3.

Generation of complex patterns. GelMA patterns of (A) Sir Isaac Newton and (B) kidney vasculature. Scale bar: 500 μm (C) Confocal sections of bilayer hydrogels containing line patterns showing the X-Z plane and X-Y planes at indicated z positions. Horizontal scale bar: 150 μm. Vertical scale bar: 25 μm. (D) 3D reconstruction of the GelMA structures in the bilayer constructs. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/tec

We have also created multilayered supported structures using this approach. Specifically, we generated a bilayer scaffold consisting of line patterns of ∼100 μm width, with spacing of 500 μm (Fig. 3C). X-Y confocal sections of the structure at various Z planes indicate two different GelMA line patterns perpendicular to each other. The X-Z cross-section of this multilayered structure indicates that the two GelMA lines are integrated at the interface between the layers. One of the current caveats of multilayered patterning approaches is the lack of structural stability with the additional stacks often leading to structural collapse. In our study, we did not observe any such collapsing of the GelMA upper layer irrespective of the distance between the line GelMA structures in the lower layer. This is mainly due to the supporting hydrogel, which provided the mechanical integrity and support to the patterned GelMA structures, thereby circumventing the inherent mechanical instability. Figure 3D shows the 3D reconstructed images of the bilayer patterns.

Cell encapsulation

We encapsulated multiple cells within the GelMA structures to assess the cytocompatibility of the 3D photopatterning technique. Figure 4A demonstrates the viability of hMSCs encapsulated within a cylindrical patterned structure of ∼250 μm diameter surrounded by another hydrogel layer. The cells were labeled with green dye before encapsulation to visualize their distribution within the patterned structure (Fig. 4A, left column). Live–dead analyses of the encapsulated cells indicate that majority of the cells remain viable postencapsulation (Fig. 4A, right column). A similar encapsulation experiment was also performed with the bilayer line structures. The hMSCs were encapsulated in both the top and bottom line structures (Fig. 4B). Similar to the cylindrical patterns, majority of the cells within the line patterns were found to be viable (Fig. 4B, right column).

We next determined the ability of the cell-encapsulation with 3D patterning to create spatially distinct coculture systems. To this end, we have encapsulated HUVECs and MDA-MB-231s where MDA-MB-231 cells were first encapsulated within cylindrical patterns, and HUVECs were encapsulated within the hydrogel layer surrounding the initial patterns. The images obtained from live/dead assay performed 3 days post-encapsulation illustrates the dense cluster of cancer cells within the circular regions with sparse distribution of surrounding HUVECs (Fig. 4C). Second, another approach to coculture, relying on alignment of the photomask, was performed with HUVECs and human fibroblasts, where the two cell types were encapsulated in a spatially confined manner, both within cylindrical 3D patterned structures. The cells were labeled with fluorescent dyes before their encapsulation. The HUVECs, shown in red, and fibroblasts, shown in green, were spatially confined in distinct and alternate positions by photopolymerizing GelMA solutions containing the respective cells in a two-step process (Fig. 4D).

Discussion

Advances in bioprinting have led to the advent of a broad range of approaches to create hierarchical 3D structures with and without cells. However, the widespread use of this technology has been limited due to the requirement of sophisticated equipment and expertise. Herein, we demonstrated an easy-to-adapt biofabrication technique, which can be used to create 3D structures with varying height, size, shape, and complexity.

When encapsulated, the cells were found to be viable within these structures. Both GelMA and PEGDA are biocompatible and have been extensively used for 3D cell culture systems.3,7,24,30,32 In this study, we opted to encase the patterned structures within a continuous, or nonpatterned, surrounding hydrogel layer. Besides providing mechanical integrity and ease of handling, the surrounding hydrogel layer could be doped with biochemical cues and other cell types to create morphogenic gradients and heterotypic cell–cell interactions. Particularly, if one chose to engineer integrated tissues within the patterned structures and encapsulate the HUVEC cells within the surrounding hydrogel layer that could lead to vascularization of the tissues.

Figure 4C and D were constructed as a proof of concept coculture systems because a number of studies have shown the importance of homotypic and heterotypic cell–cell interactions.35,36 Although the demonstration involves only two cell types, the process can be used to encapsulate many more cell types within the same system without overexposing majority of the cells to UV. In addition to the cell phenotype and cell density, the distance between the 3D structures confined with the cells can be easily varied to create morphogen gradients to study the impact of cell–cell communication through soluble factors.

While the photopatterning process described in this study offers an easy-to-use and highly adaptable method to create 3D structures with various architectures, the method suffers from a few limitations compared to 3D printing. The technique's dependence on the photomask to extrude patterns with multiple features of varying size could affect the resolution of the structure dimensions, especially for structures with multiple intricate features such as in Isaac Newton's portrait. Since small features require more polymerization time, when larger features are extruded together with these small features, they tend to overpolymerize as radicals diffuse outward from the polymerization site at UV exposure durations required for the smaller features to form. On the other hand, shorter durations required to polymerize large features may be insufficient for the smaller features to form. Thus, when a single gelation time is used for the entire pattern, it is possible for the features' results in GelMA patterns to not coincide with the dimensions of design on the photomasks. In addition, there are limitations to the overall height of the patterns since the coverslip placed onto the large volume of the precursor solutions could tilt resulting in features with uneven heights. Nonetheless, the photopatterning methodology described in this study offers sufficient promise for homogeneous and multicell cultures requiring spatial organization in 3D. Since the protocol relies only on a photomask and collimated UV, it could be easily adapted. Such technological platforms could be used to study cell-–matrix and cell–cell interactions in a defined 3D environment and to create hierarchical cell-laden structures to engineer complex tissues.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Jomkuan Theprungsirikul for her assistance with taking the photographs. Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R01 AR063184-02 and the California Institute of Regenerative Medicine (grant RT3-07907). AA would like to acknowledge the support from Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Award NIH/NHLBI T32 HL 105373, and ARCS Foundation. The authors also acknowledge the University of California San Diego Neuroscience Microscopy Shared Facility funded through NS047101. The hMSCs used in this study were provided by the Institute for Regenerative Medicine, Texas A&M University, through Grant P40RR017447 from the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR) of the NIH.

Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Discher D.E., Mooney D.J., and Zandstra P.W. Growth factors, matrices, and forces combine and control stem cells. Science 324, 1673, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Khetan S., Guvendiren M., Legant W.R., Cohen D.M., Chen C.S., and Burdick J.A. Degradation-mediated cellular traction directs stem cell fate in covalently crosslinked three-dimensional hydrogels. Nat Mater 12, 458, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kang H., Shih Y.R., Hwang Y., Wen C., Rao V., Seo T., and Varghese S. Mineralized gelatin methacrylate-based matrices induce osteogenic differentiation of human induced pluripotent stem cells. Acta Biomater 10, 4961, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Benoit D.S., Schwartz M.P., Durney A.R., and Anseth K.S. Small functional groups for controlled differentiation of hydrogel-encapsulated human mesenchymal stem cells. Nat Mater 7, 816, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Huebsch N., Arany P.R., Mao A.S., Shvartsman D., Ali O.A., Bencherif S.A., Rivera-Feliciano J., and Mooney D.J. Harnessing traction-mediated manipulation of the cell/matrix interface to control stem-cell fate. Nat Mater 9, 518, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lim H.L., Chuang J.C., Tran T., Aung A., Arya G., and Varghese S. Dynamic electromechanical hydrogel matrices for stem cell culture. Adv Funct Mater 21, 55, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Varghese S., Hwang N.S., Ferran A., Hillel A., Theprungsirikul P., Canver A.C., Zhang Z., Gearhart J., and Elisseeff J. Engineering musculoskeletal tissues with human embryonic germ cell derivatives. Stem Cells 28, 765, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mosiewicz K.A., Kolb L., van der Vlies A.J., Martino M.M., Lienemann P.S., Hubbell J.A., Ehrbar M., and Lutolf M.P. In situ cell manipulation through enzymatic hydrogel photopatterning. Nat Mater 12, 1072, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wade R.J., Bassin E.J., Gramlich W.M., and Burdick J.A. Nanofibrous hydrogels with spatially patterned biochemical signals to control cell behavior. Adv Mater 27, 1356, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ali S., Cuchiara M.L., and West J.L. Micropatterning of poly(ethylene glycol) diacrylate hydrogels. Methods Cell Biol 121, 105, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wylie R.G., Ahsan S., Aizawa Y., Maxwell K.L., Morshead C.M., and Shoichet M.S. Spatially controlled simultaneous patterning of multiple growth factors in three-dimensional hydrogels. Nat Mater 10, 799, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kolesky D.B., Truby R.L., Gladman A.S., Busbee T.A., Homan K.A., and Lewis J.A. 3D bioprinting of vascularized, heterogeneous cell-laden tissue constructs. Adv Mater 26, 3124, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tsang V.L., and Bhatia S.N. Three-dimensional tissue fabrication. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 56, 1635, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Soman P., Chung P.H., Zhang A.P., and Chen S. Digital microfabrication of user-defined 3D microstructures in cell-laden hydrogels. Biotechnol Bioeng 110, 3038, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Khetan S., and Burdick J.A. Patterning network structure to spatially control cellular remodeling and stem cell fate within 3-dimensional hydrogels. Biomaterials 31, 8228, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Khetan S., and Burdick J.A. Patterning hydrogels in three dimensions towards controlling cellular interactions. Soft Matter 7, 830, 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Murphy S.V., and Atala A. 3D bioprinting of tissues and organs. Nat Biotechnol 32, 773, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.DeForest C.A., and Anseth K.S. Cytocompatible click-based hydrogels with dynamically tunable properties through orthogonal photoconjugation and photocleavage reactions. Nat Chem 3, 925, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Arcaute K., Mann B.K., and Wicker R.B. Stereolithography of three-dimensional bioactive poly(ethylene glycol) constructs with encapsulated cells. Ann Biomed Eng 34, 1429, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Grogan S.P., Chung P.H., Soman P., Chen P., Lotz M.K., Chen S., and D'Lima D.D. Digital micromirror device projection printing system for meniscus tissue engineering. Acta Biomater 9, 7218, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sala A., Hanseler P., Ranga A., Lutolf M.P., Voros J., Ehrbar M., and Weber F.E. Engineering 3D cell instructive microenvironments by rational assembly of artificial extracellular matrices and cell patterning. Integr Biol (Camb) 3, 1102, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee S.H., Moon J.J., and West J.L. Three-dimensional micropatterning of bioactive hydrogels via two-photon laser scanning photolithography for guided 3D cell migration. Biomaterials 29, 2962, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu Tsang V., Chen A.A., Cho L.M., Jadin K.D., Sah R.L., DeLong S., West J.L., and Bhatia S.N. Fabrication of 3D hepatic tissues by additive photopatterning of cellular hydrogels. FASEB J 21, 790, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Underhill G.H., Chen A.A., Albrecht D.R., and Bhatia S.N. Assessment of hepatocellular function within PEG hydrogels. Biomaterials 28, 256, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bryant S.J., Cuy J.L., Hauch K.D., and Ratner B.D. Photo-patterning of porous hydrogels for tissue engineering. Biomaterials 28, 2978, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Papavasiliou G., Songprawat P., Perez-Luna V., Hammes E., Morris M., Chiu Y.C., and Brey E. Three-dimensional patterning of poly (ethylene Glycol) hydrogels through surface-initiated photopolymerization. Tissue Eng Part C Methods 14, 129, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.DeForest C.A., Polizzotti B.D., and Anseth K.S. Sequential click reactions for synthesizing and patterning three-dimensional cell microenvironments. Nat Mater 8, 659, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kloxin A.M., Kasko A.M., Salinas C.N., and Anseth K.S. Photodegradable hydrogels for dynamic tuning of physical and chemical properties. Science 324, 59, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liu V., and Bhatia S. Three-dimensional photopatterning of hydrogels containing living cells. Biomed Microdev 4, 257, 2002 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hutson C.B., Nichol J.W., Aubin H., Bae H., Yamanlar S., Al-Haque S., Koshy S.T., and Khademhosseini A. Synthesis and characterization of tunable poly(ethylene glycol): gelatin methacrylate composite hydrogels. Tissue Eng Part A 17, 1713, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lin S., Sangaj N., Razafiarison T., Zhang C., and Varghese S. Influence of physical properties of biomaterials on cellular behavior. Pharm Res 28, 1422, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fairbanks B.D., Schwartz M.P., Bowman C.N., and Anseth K.S. Photoinitiated polymerization of PEG-diacrylate with lithium phenyl-2,4,6-trimethylbenzoylphosphinate: polymerization rate and cytocompatibility. Biomaterials 30, 6702, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yang X., Sarvestani S.K., Moeinzadeh S., He X., and Jabbari E. Three-dimensional-engineered matrix to study cancer stem cells and tumorsphere formation: effect of matrix modulus. Tissue Eng Part A 19, 669, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Marxen M., Sled J.G., Yu L.X., Paget C., and Henkelman R.M. Comparing microsphere deposition and flow modeling in 3D vascular trees. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 291, H2136, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Aung A., Gupta G., Majid G., and Varghese S. Osteoarthritic chondrocyte-secreted morphogens induce chondrogenic differentiation of human mesenchymal stem cells. Arthritis Rheum 63, 148, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hui E.E., and Bhatia S.N. Micromechanical control of cell-cell interactions. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 104, 5722, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.