Abstract

Objectives. We systematically reviewed the Environmental Protection Agency, National Center for Environmental Research’s (NCER’s) requests for applications (RFAs) and identified strategies that NCER and other funders can take to bolster community engagement.

Methods. We queried NCER’s publically available online archive of funding opportunities from fiscal years 1997 to 2013. From an initial list of 211 RFAs that met our inclusion criteria, 33 discussed or incorporated elements of community engagement. We examined these RFAs along 6 dimensions and the degree of alignments between them.

Results. We found changes over time in the number of RFAs that included community engagement, variations in how community engagement is defined and expected, inconsistencies between application requirements and peer review criteria, and the inclusion of mechanisms supporting community engagement in research.

Conclusions. The results inform a systematic approach to developing RFAs that support community engagement in research.

Partnerships between communities and institutional researchers offer a powerful approach for conducting research by strengthening the understanding of real world concerns, identifying solutions to problems communities face, and generating new forms of knowledge to address health inequities. Community engagement in research provides an opportunity to have demonstrable and meaningful effects in communities.

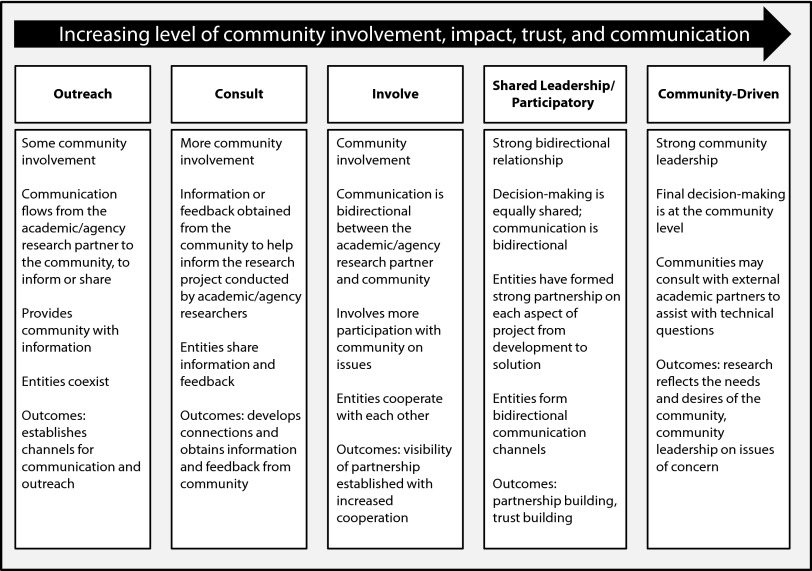

Community-engaged research is commonly described as a continuum of community engagement in research activities1–5 and a framework for how institutional researchers can partner with communities to strengthen the reach, rigor, and relevance of science.6 Engaging the community in the research process is not a uniform or “one-size-fits-all” approach, and roles and responsibilities can fall along a spectrum that ranges from very limited involvement to a research process directly owned and managed by the community (Figure 1).7–9

FIGURE 1—

Continuum of community engagement in research: 1997–2013.

Source. Modified from the Clinical and Translational Science Awards Consortium8 and the International Association for Public Participation.9

Where a particular study falls along this continuum depends on numerous factors that include the values, interests, and capacities of the researchers and community partners as well as the study focus and specific aims. Funding agencies play an important role in shaping community engagement by prescribing parameters for funding that can either facilitate or hinder whether and how community is engaged.10

The US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has begun to prioritize community engagement strategies to achieve its mission of protecting human health and the environment and addressing environmental injustices that disproportionately affect low-income communities and communities of color.11 Community engagement has been highlighted as a key facet of the agency’s research efforts to support environmental justice objectives by improving the quality of information, the interpretation of data, and the ability of research to highlight strategies to reduce the burden of impact on vulnerable populations.12–13

The inclusion of community-engaged research in the EPA’s extramural research portfolio is also responsive to the National Environmental Justice Advisory Council’s recommendations to integrate environmental justice into the agency’s scientific foundation.14 The National Center for Environmental Research (NCER), the extramural research program of the EPA, is exploring opportunities to further support and expand community participation in its Science to Achieve Results (STAR) research programs. The STAR program is a competitive, peer-reviewed, extramural research grants program created to support research fields relevant to the EPA’s mission. In fiscal year (FY) 2013, the STAR program awarded $29.4 million to 91 research recipients.15

We investigated how NCER has incorporated and communicated community engagement in its extramural research program through a review of its requests for applications (RFAs). RFAs are an essential mechanism by which funders articulate to prospective applicants the aims and expected outcomes of the research they support. RFAs play a critical role in clarifying the purpose and components of community engagement in the research context. We have highlighted strategies that NCER and other funders can take to bolster community engagement in their research programs.

METHODS

We queried NCER’s publicly available online archive of funding opportunities from FY1997 to FY2013.16 From an initial list of 317 RFAs identified, we excluded 106 RFAs that did not pertain to the STAR research program, were cancelled, or lacked available text that could be reviewed. We examined the texts of the remaining 211 RFAs to determine whether community engagement concepts were included using a keyword search as a general guide: community engagement, community involvement, community participation, and community-based participatory research (CBPR). Of the 211 RFAs, 33 RFAs (16%) discussed or incorporated elements of community engagement, and we included them in the review.

We examined the text of the 33 RFAs along 6 dimensions:

level of community engagement described: outreach, community participation, and CBPR;

the degree to which the RFA required community engagement: optional or mandatory;

definition of community and community engagement;

description of expected outputs and outcomes;

application and submission requirements; and

peer review criteria.

We also enumerated and calculated the percentage of RFAs that included community engagement and examined trends over time.

We defined community outreach as the communication and explanation of data, risks, or the use of tools to community stakeholders by the applicant research team. We defined community participation as the inclusion of community members in some aspect of the research process, with their roles and responsibilities ranging from minimal to highly involved. We defined CBPR as a

collaborative approach to research that equitably involves all partners in the research process and recognizes the unique strengths that each brings. CBPR begins with a research topic of importance to the community and has the aim of combining knowledge with action and achieving social change to improve health outcomes and eliminate health disparities.17(p2)

We further assessed RFAs that explicitly discussed CBPR, and used the term CBPR to describe a research approach, for how they defined and described CBPR, their inclusion of resources to support CBPR (e.g., the use of external advisory committees, data-sharing plans), and their assessment of investigator and institutional capacity to engage in CBPR. We considered community engagement to be optional if the RFA described or suggested it and mandatory if it was required for funding.

RESULTS

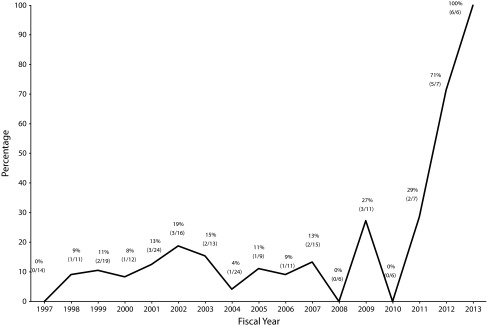

A summary of our findings from examining the 33 RFAs is presented in Table 1. (Supplemental materials are available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org.) Figure 2 depicts temporal changes regarding the inclusion of community engagement in STAR RFAs. Fiscal years 2012 (71%) and 2013 (100%) had the highest percentages of RFAs that included community engagement. Beginning in FY2012, all RFAs were required to include EPA template language regarding human participant research and possible researcher–community interactions, which explains the higher rates seen in FY2012 and FY2013. For 4 of the 6 FY2013 RFAs we analyzed, the mandatory human participant research template language was their only reference to community engagement.

TABLE 1—

Summary of Findings From the Examination of 33 RFAs Discussing Community Engagement: Environmental Protection Agency, Science to Achieve Results; United States; 1997–2013

| Dimensions | RFAs, No. (%) |

| Level of community engagementa | |

| Community outreach | 15 (45) |

| Community participationb | 21 (64) |

| CBPR | 11 (33) |

| Degree of requirement for level of community engagementa | |

| Mandatory | 26 (78) |

| Optionalb | 14 (42) |

| Multiple degrees of requirement | 7 (21) |

| Single degree of requirement | 26 (79) |

| Definition of community and community engagement | |

| Included definition of community | 4 (12) |

| Described or defined community engagement | 11 (33) |

| Expected outputs and outcomes of research described community engagement as outcome | 10 (30) |

| Application and submission requirements discussed submission of additional informationb | 30 (91) |

| Included peer review criteria | 23 (70) |

Note. CBPR = community-based participatory research; RFA = requests for applications.

Multiple levels and degrees of requirement for community engagement are feasible; these do not tally to 100%.

Environmental Protection Agency human subjects research template language is reflected.

FIGURE 2—

Number and percentage of Environmental Protection Agency Science to Achieve Results requests for applications that include community engagement: 1997–2013.

Level of Community Engagement and Degree of Requirement

Community participation was the most frequently discussed level of community engagement (64%). The majority of RFAs (79%) made community engagement a mandatory component of the application. Seven RFAs (21%) incorporated multiple degrees of requirement for the levels of community engagement described. For example, the FY2013 Healthy Schools: Environmental Factors, Children’s Health and Performance, and Sustainable Building Practices RFA mandated a community-engaged research plan and encouraged applicants to apply CBPR principles but considered a range of levels of community involvement, asking the applicant to justify the level of community engagement proposed.18

Table 2 depicts the level of engagement cross-tabulated by the degree of requirement across the 33 RFAs.

TABLE 2—

Level of Engagement by Degree of Requirement: Environmental Protection Agency, Science to Achieve Results; United States; 1997–2013

| RFAs by Level of Engagement, No. |

|||

| Degree of Requirement | Outreach | Community Participation | CBPR |

| Optional | 1 | 8 | 5 |

| Required | 14 | 13 | 6 |

| Totals | 15 | 21 | 11 |

Note. CBPR = community-based participatory research; RFA = requests for applications.

Definition of Community and Community Engagement

Only 4 RFAs (12%) included definitions of community. The definitions were varied and included both individuals who are members of a community and organizations and professions that may represent a community’s interests. Example definitions of community in the RFAs include the following:

Communities are groups of people with diverse characteristics who are linked by social ties, share common perspectives, and engage in joint action in similar geographical locations.

Communities can also develop around a particular interest, issue, identity, or subject matter and may include professional communities, such as lawn care, transportation, and land use planning.

Eleven RFAs (33%) described a definition, model, or framework for community engagement. For example, the RFA Environmental Justice: Partnerships for Communication described community engagement as “community actively participates with researchers and health care providers in developing responses and setting priorities for intervention strategies.”19

Expected Outputs and Outcomes of Research

Ten RFAs (30%) discussed community engagement as an outcome of research. For example, the FY2002 Lifestyle and Cultural Practices of Tribal Populations and Risks From Toxic Substances in the Environment RFA included community engagement as both a requirement for the project and an expected outcome with the development of new partnerships.20

The 2 Sustainable Chesapeake research RFAs sought increased community engagement and innovative community-based governance concerning storm water management as an expected part of the research and as an anticipated outcome.21,22

Application and Submission Requirements

Thirty RFAs (91%) discussed the submission of additional information describing the proposed community engagement strategy. For example, the FY2013 Science for Sustainable and Healthy Tribes RFA requested a tribal CBPR plan detailing community involvement, such as how the research is of significance to the tribe, the role of tribal community members in the research plan, the ability of the research to enhance tribal community capacity, and how research findings are disseminated to the tribal community. As another example, the new EPA Human Subjects Research Statement requirement asked applicants to respond to the following:

If the research will take place in a community setting, describe the procedures in place for defining the community, obtaining its involvement in the research, and establishing and maintaining trust.18

Three RFAs (9%) discussed community engagement in the description or background sections of the RFA yet did not outline any application and submission parameters to be submitted in applicants’ proposals. A list of application and submission information regarding community engagement is shown in the box on page e48.

Examples of Community Engagement–Related Information Requested in Environmental Protection Agency Science to Achieve Results Requests for Applications: United States, 1997–2013

| Effective Engagement | Additional Resources to Support Partnership | Applicants’ Qualifications and Readiness |

| Demonstrate how research will focus on issues of significance to communities. | Potentially include the use of subgrants awarded to pay for community-based organizations or community members’ participation. | Provide evidence of community support. |

| Discuss how communities can effectively participate in the design and performance of the research project. | Describe data-sharing plan with community. | Describe personnel expertise and experience or past interactions with other organizations. |

| Describe the results expected to be achieved through community involvement and the potential benefits to the communities and other stakeholders. | Articulate plan for the dissemination of research findings. | Demonstrate the ability to engage community of concern in implementing culturally relevant strategies (e.g., tribal knowledge). |

| Identify the role of community members. | Include resources for partnership development, such as a Community Outreach and Translation Core. | |

| Show how the research will enhance the capacity of the community. | ||

| Describe the procedures in place for defining the community, obtaining its involvement in the research, and establishing and maintaining trust.a |

Reflects Environmental Protection Agency human subjects research template language.

Peer Review Criteria

Peer review criteria of community engagement varied widely. Twenty-three RFAs (70%) included peer review criteria of proposed community engagement activities. In the RFAs that included peer review criteria, there was wide variation in the detail and criteria involved. Some RFAs, mostly related to CBPR, described more in-depth peer review criteria.

Other RFAs simply asked reviewers to determine whether the activities described promote learning and outreach or broaden participation of socioeconomically disadvantaged groups.

Community-Based Participatory Research Analysis

Eleven RFAs (33%) discussed CBPR. Of those, more than half (55%) were solicitations for the Centers for Children’s Environmental Health and Disease Prevention Research, which are research centers established to better understand the effects of exposures to environmental contaminants on children.23 These centers have a long history of including CBPR.24 Fifty-five percent of the CBPR RFAs made the inclusion of CBPR mandatory.

Definitions and description of CBPR varied across the RFAs; 1 RFA did not provide a definition. “Equitable and substantial community involvement throughout the research process”25,26 was a common phrase used to define CBPR. Some RFAs also described CBPR as a “collaborative process of research,”21 a “partnership approach,”40 and “a collaborative research method that involves the commitment to balance the power dynamic by equally engaging all partners throughout the research process.”41 CBPR was also defined as consulting with key stakeholders to consider their views in research design or translation.

Additional measures were specified in these RFAs to help applicants implement CBPR. These included the following:

Community outreach and translation cores and community liaisons: Many of the Children’s Environmental Health Center RFAs describe the implementation of community outreach and translation cores to coordinate community engagement efforts and translate the scientific findings for use by the public and policymakers.

External advisory committees and community advisory boards: The use of an external advisory committee or community advisory board was discussed in several of the RFAs, often to be made up of at least 1 representative from a community-based organization involved in community-based research.

Funding mechanisms: Subgrants or subawards of financial assistance were described to support partnerships. In 1 RFA, 20% to 35% of the budget could have been devoted to a single CBPR project.25

Data-sharing plans: Two RFAs describe data-sharing plans that would make all data results available in formats that can be used by community partners.26,27

Three RFAs described provisions to evaluate the investigators’ capacity to engage with communities, such as whether the collaborators and other researchers are well suited to the project and whether the investigators have complementary and integrated expertise. In some cases, an organization’s mission and practices concerning community partnership may also be evaluated. In the Children’s Environmental Health Centers, whether community outreach and translation core members can help fulfill the mission may be evaluated.

Nearly all the CBPR-related RFAs (90%) outlined more substantive peer review criteria to evaluate community engagement or CBPR plans, such as whether the activities were appropriate to the needs of the community involved; mechanisms for regular communication and coordination; and how stakeholders are involved in aspects of the center’s activities.

DISCUSSION

The findings of our RFA analysis point to several observations we believe are worthy of further discussion.

Changes in Requests for Applications With Community Engagement

During the first 16 years of NCER’s operations (FY1997–FY2012), 13% of all RFAs included community engagement (with a range of 0%–71% per year). Beginning in FY2013, 100% of STAR RFAs included language about community engagement; however, this was mostly because of the new required EPA human participant research template language. Over the 17-year study period (FY1997–FY2013), we identified 33 RFAs that included community engagement language. These 33 RFAs are a combined total of approximately $327 million in research funding out of $1.25 billion (26.2%) of EPA’s extramural research investment in the STAR research program.

In the past few years, the number and percentage of RFAs that include community engagement began to climb. This may be attributed in part to deliberate decisions about EPA’s strategic directions and changes in EPA policy, including an increased focus on advancing environmental justice, enhanced protections for human participants, and greater recognition among the research community of the value of community engagement.9,28

Variation in How Community Engagement Is Defined and Expected

We found variation in how STAR RFAs defined community engagement. Defining it broadly and considering it optional provides applicants with the maximum flexibility in determining why, whether, and how to incorporate community engagement into the research they propose. Providing definitions of these important terms, however, can convey a funder’s intentions and minimize applicants’ interpretations that fall outside what was intended.29

The inclusion of different stakeholders that represent various and possibly conflicting interests can have significant implications for the design and implementation of the research project, data analysis, interpretation of results, and dissemination of findings. More importantly, it can also have implications for equity and environmental justice by shaping who has access to and influence on the research process and outcomes.

Application Requirements vs Peer Review Criteria

Peer review criteria communicate to both applicants and reviewers the qualities and characteristics of the proposed research that are most important and how they will be evaluated. We found that a large percentage (33%) of RFAs did not carry their application requirements for community engagement through to their peer review criteria. For example, the FY2007 Issues in Tribal Environmental Research and Health Promotion: Novel Approaches for Assessing and Managing Cumulative Risks and Impacts of Global Climate Change RFA mandated community participation; however, language in the review criteria did not reflect this requirement.

Additionally, the required EPA Human Subjects Research Statement is considered only by the EPA human participant research review official and not by the peer review panel. This inconsistency is problematic because it makes the importance of community engagement unclear. It also fails to ensure that peer reviewers will assess it.

Explicitly Supporting Community Engagement in Research

Our analysis of the RFAs that incorporated CBPR demonstrated a variety of means for facilitating community engagement in research, including dedicated positions, governing and advisory bodies, and specific mechanisms for compensating community partners for their time and expertise.

Although we analyzed and discussed these in relation to CBPR only, they could be more broadly applicable.10

Study Limitations

There are several limitations to our study. First, because we did not analyze the content areas and goals of all 211 RFAs retrieved, we are unable to comment on the NCER RFA research topics and categories that more commonly include community engagement. We did not examine secular trends in the demand and benefit of community engagement.

Second, because we limited our analysis to the language contained in RFAs that discussed community engagement, we are unable to comment on processes outside developing RFAs, most notably the peer review and award selection processes. The challenges of constructing peer review panels that have the expertise required to assess community engagement in research have been previously described.30,31

Finally, we are unable to relate the community engagement language in RFAs to the results of the peer review of applications, the decisions that were made about which to fund, and how any community engagement proposed in a selected application was actually implemented in practice. All these limitations point to fruitful areas of further investigation.

Study Implications

Our findings can inform a systematic approach to RFA development for other funders that seek to support community engagement in research as a strategy for advancing health equity and environmental justice.32 Strategies and considerations for funders that support community engagement in research are presented as a set of questions in the box on page e49.

Questions to Guide Funding Agency Decisions About Community Engagement in Research Request for Applications

| Decision Nodes | Questions for Consideration |

| Include community engagement | Are there community concerns that may be relevant to the development or execution of the research program? |

| Are there likely to be impacts, either direct or indirect, on communities or sensitive subpopulations (e.g., children, senior citizens, and low-income, minority, or tribal populations)? | |

| Could community knowledge or tribal ecological knowledge or experiences contribute positively to the research? | |

| Are there opportunities to engage with communities directly in any phase of the research process or in the dissemination of findings? | |

| Determine the vision for community engagement | In what ways might involving the community benefit the research? |

| What is the ultimate goal of involving the community in the research program? | |

| What are some motivating factors for community members’ and tribes’ participation? | |

| What would they expect to gain from participating? | |

| In what aspects may community members and tribes be involved in the research? | |

| Define community and community engagement | What are the definitions of community, community engagement, and related terms to be used in the request for applications? |

| Who or what groups, populations, or categories of people are and are not intended to be engaged? | |

| Specify level of involvement and degree of requirement | Will community engagement be required or optional? |

| Will the level of community engagement be predetermined in the request for application or determined and justified by the applicant? | |

| Should template language related to community engagement be included in all request for applications? | |

| Time frame and funding mechanism | Will the funding cycle be single grants or multiphase grants (e.g., planning, implementation)? |

| Is the duration of grant funding reasonably aligned with the expected level and degree of community engagement? | |

| Measures to support community engagement | What measures (e.g., community organization as the grantee, subawards for community partners, minimum percentage of the budget to the community partner, community engagement infrastructure, community advisory bodies, community with decision-making authority, community ownership of data) will be included in the request for application that support community engagement? |

| Will these measures be presented as optional ideas for consideration, expected, or required? | |

| Application and submission information | What community engagement information will be sought from applicants (e.g., community engagement plan, data-sharing plan, demonstration of qualifications and past partnerships, letters of support from community partners)? |

| Will this information be presented as optional for consideration, expected, or required? | |

| Peer review considerations | What peer review criteria will be used to assess community engagement? |

| Is there alignment of the level and degree of community engagement expected in applications with the peer review criteria? | |

| Expected outputs and outcomes | What outputs and outcomes of community engagement will be sought in applications (e.g., incorporation of community or tribal knowledge, reporting on lessons learned through community engagement, demonstration of community benefit, building community capacity, economic benefit for the community, community ownership of data)? |

| Will these be presented as optional for consideration, expected, or required? |

Community engagement may not be applicable to all research contexts, and an assessment could be conducted to determine whether it is needed to a lesser degree. The questions in the box on the previous page may help elucidate whether community engagement would be beneficial to include in a particular RFA, and, if so, they may help guide decisions about the definitions and components to include.

Acknowledging that there is no single definition of community and that communities are not homogenous, a particular RFA should define the term in the context of community engagement in research. Providing these definitions will help facilitate applications better suited to meeting the objectives of the research program’s inclusion of community engagement. For example, a particular RFA might define the community as individuals most directly affected by the problem or issue under study and exclude academic institutions as community partners.

Specifying the level of engagement and the degree to which it is required in a RFA is an important consideration because it determines the parameters of what applicants propose and how it is reviewed. Predetermining the level of engagement and requiring it allows the funder to maintain significant control over what is proposed and reviewed. Embedding a question with related peer review criteria in template RFA language is a strategy to ensure that community engagement is considered. Allowing the applicant to define the level of community engagement may permit a more reasoned explanation of how it would benefit the proposed research and how it will be incorporated.

The funding mechanism and timeframe should align with the goals of the RFA and its level of engagement.33,34 A typical grant cycle often does not allow the time needed to develop and maintain relationships, meaningfully engage communities, conduct the research, disseminate the findings, and act on them. A possible strategy to address this concern is a sequential series of funding opportunities. An example is the CBPR Initiative in Reducing and Eliminating Health Disparities created by the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities.35 The initiative has 3 funding phases: a 3-year planning grant, a 5-year intervention grant and intervention study, and a 3-year dissemination grant.

Planning grant mechanisms can focus on creating the relationships and infrastructure necessary for developing and maintaining partnerships and better prepare applicants for other phases of the research execution.33 Alternatively, an elongated grant cycle, beyond the usual 3-year timeframe, could provide the time needed to organize, plan, and conduct the research.10 This option would require that funders be prepared to support projects that do not fully specify up front all aspects of the project, because some of the research planning would occur in the initial part of the timeline.33

Funding announcements can require or encourage mechanisms for supporting community engagement. Requiring the community partner to be the grantee, requiring a certain percentage of the budget for the community partner, flexible budget guidance, and subawards can ensure funds to compensate community partners for their roles.10 Community advisory bodies can provide community review of the study’s progress, assist in ensuring adherence to research ethics protocols, and provide a structured venue to guide the study.36,37 Community engagement administrative cores with dedicated staff can provide the infrastructure needed to support sustained engagement. Because community engagement can raise unique ethical considerations, the RFA might require applicants to address those concerns in the application.1,3

Additional applicant and submission information can assist in evaluating an application’s community engagement activities and an applicant’s capacity to carry them out. Community engagement plans can provide a detailed overview of engagement strategies and delineate the roles of the community partner and institution in the research and the outreach and dissemination plans. Data-sharing plans can specify equal access to data or ownership of the data by the community partner, such as for community-owned and managed research or in tribal research. Information on the applicants’ partnership history and community engagement competencies can demonstrate commitment. Letters of support from community partners can demonstrate willingness to engage in the proposed research as described.

The use of criteria for appraising community engagement in research helps to structure the review process to be transparent.5,38 High-quality research design and high-quality community engagement are not mutually exclusive objectives and can be intertwined and mutually reinforcing.39 Consistency between application and submission requirement and peer review criteria is an important consideration for ensuring adequate review of the community engagement strategies proposed. For instance, having community engagement template RFA language would be sufficient if it is additionally considered in the peer review. Additionally, peer review committees evaluating community engagement proposals ought to include reviewers with expertise in community-engaged research.

Outputs and outcomes as specified in the RFA related to community engagement could be reported to the funder in periodic progress reports. Probable outputs and outcomes of community-engaged research could be models or methods to incorporate community knowledge; lessons learned from engagement efforts; ways the research produced community benefits, including economic benefit; new problem-solving mechanisms to improve the translation of research; evaluation for how well community engagement efforts adhered to the community engagement plan; and impacts of the research process and findings.

Conclusions

Funders play a critical role in shaping research, including the nature and extent of community engagement. In this first assessment of language contained in EPA’s NCER announcements, we identified ways funders can shape and support community engagement in research through the application and submission process and peer review criteria.

Recommendations for funders who seek to support community engagement in research include providing a clear definition of community and community engagement, specifying the level of community engagement expected and degree of requirement with accompanying peer review criteria to assess, ensuring a grant structure and timeframe suitable for community engagement, and specifying specific outputs or outcomes of community engagement in research. The use of template language is a strategy for requiring community engagement in all RFAs and should be evaluated in the peer review criteria. Funders may enhance the relevance and rigor of research by considering these recommendations for including and requiring community engagement in research. Prescribing parameters for community engagement may ensure that all research is relevant and has an impact.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and the Association of Schools and Programs of Public Health (cooperative agreement X3-83388101) and was partly funded by the EPA (contract EP-W-09-11, task order 116, subcontract SRAS000772).

Human Participant Protection

This study is an evaluation of the publicly available online archive of the US Environmental Protection Agency’s research solicitations and therefore did not require institutional review board review.

References

- 1.Ross LF, Loup A, Nelson RM et al. Human subjects protections in community-engaged research: a research ethics framework. J Empir Res Hum Res Ethics. 2010;5(1):5–17. doi: 10.1525/jer.2010.5.1.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McDonald MA. Practicing community-engaged research. Duke Center for Community Research. Available at: https://www.citiprogram.org/citidocuments/Duke%20Med/Practicing/comm-engaged-research-4.pdf. Accessed October 10, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 3. University of Southern California. Frequently asked questions about community-engaged research. University of Southern California’s Office for the Protection of Research Subjects. Available at: http://oprs.usc.edu/files/2013/01/Frequently_Asked_Questions_about_Community-Engaged_Research.pdf. Accessed January 20, 2014.

- 4.Handley M, Pasick R, Potter M, Oliva G, Goldstein E, Nguyen T. Community-engaged research: a quick-start guide for researchers. 2010. Available at: http://accelerate.ucsf.edu/files/CE/guide_for_researchers.pdf. Accessed January 20, 2014.

- 5.Ahmed SM, Palermo AS. Community engagement in research: frameworks for education and peer review. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(8):1380–1387. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.178137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Balazs CL, Morello-Frosch R. The three Rs: how community-based participatory research strengthens the rigor, relevance, and reach of science. Environmen Justice. 2013;6(1):9–16. doi: 10.1089/env.2012.0017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Heaney CD, Wilson SM, Wilson OR. The West End Revitalization Association’s community-owned and -managed research model: development, implementation, and action. Prog Community Health Partnersh. 2007;1(4):339–349. doi: 10.1353/cpr.2007.0037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Clinical and Translational Science Awards Consortium. Principles of Community Engagement. 2nd ed. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 9.International Association for Public Participation. IAP2 Spectrum of Public Participation. 2007. Available at: http://www.iap2.org/associations/4748/files/spectrum.pdf. Accessed April 13, 2015.

- 10.Minkler M, Blackwell AG, Thompson M, Tamir H. Community-based participatory research: implications for public health funding. Am J Public Health. 2003;93(8):1210–1213. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.8.1210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.US Environmental Protection Agency. FY2014–2018: EPA strategic plan. 2014. Available at: http://www2.epa.gov/sites/production/files/2014-09/documents/epa_strategic_plan_fy14-18.pdf. Accessed October 12, 2014. [PubMed]

- 12.US Environmental Protection Agency. Plan environmental justice 2014: science and tools development. 2011. Available at: http://www.epa.gov/compliance/ej/resources/policy/plan-ej-2014/plan-ej-science-2011-09.pdf. Accessed October 12, 2014.

- 13.US Environmental Protection Agency. An Update on Ongoing and Future EPA Actions to Empower Communities and Advance the Integration of Environmental Justice in Decision Making and Research. Washington, DC: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 14.National Environmental Justice Advisory Council. Recommendations for integrating environmental justice into EPA’s research enterprise. 2014. Available at: http://www.epa.gov/environmentaljustice/resources/publications/nejac/nejac-research-recommendations-2014.pdf. Accessed March 10, 2015.

- 15.US Environmental Protection Agency. Science to achieve results (STAR) grants: award recipients. Extramural research. 2014. Available at: http://cfpub.epa.gov/ncer_abstracts/index.cfm/fuseaction/recipients.list/year/2013/abs_type/All. Accessed October 12, 2014.

- 16.US Environmental Protection Agency. Funding opportunities: archive. Extramural research. 2014. Available at: http://epa.gov/ncer/rfa/archive. Accessed October 12, 2014.

- 17.Faridi Z, Grunbaum JA, Gray BS, Franks A, Simoes E. Community-based participatory research: necessary next steps. Prev Chronic Dis. 2007;4(3):A70. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.US Environmental Protection Agency. Healthy schools: environmental factors, children’s health and performance, and sustainable building practices. 2013. Available at: http://epa.gov/ncer/rfa/2013/2013_star_healthy_schools.html. Accessed October 12, 2014.

- 19.US Environmental Protection Agency. Environmental justice: partnerships for communication. Extramural research. 2012. Available at: http://epa.gov/ncer/rfa/archive/grants/99/ejust99.html. Accessed October 23, 2014.

- 20.US Environmental Protection Agency. Lifestyle and cultural practices of tribal populations and risks from toxic substances in the environment. Extramural research. 2012 Available at: http://epa.gov/ncer/rfa/archive/grants/02/02trib_risk.html. Accessed October 19, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 21.US Environmental Protection Agency. Sustainable Chesapeake: a community-based approach to stormwater management. Extramural research. 2011 Available at: http://epa.gov/ncer/rfa/2011/2011_star_chesapeake.html. Accessed November 2, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 22.US Environmental Protection Agency. Sustainable Chesapeake: a community-based approach to stormwater management using green infrastructure. Extramural research. 2012 Available at: http://epa.gov/ncer/rfa/2012/2012_star_chesapeake.html. Accessed November 2, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 23.US Environmental Protection Agency. EPA/NIEHS Children’s Environmental Health and Disease Prevention Research Centers (CEHCs) 2014. Available at: http://epa.gov/ncer/childrenscenters. Accessed October 23, 2014.

- 24.Israel BA, Parker EA, Rowe Z et al. Community-based participatory research: lessons learned from the Centers for Children’s Environmental Health and Disease Prevention Research. Environ Health Perspect. 2005;113(10):1463–1471. doi: 10.1289/ehp.7675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.US Environmental Protection Agency. Centers for Children’s Environmental Health and Disease Prevention Research. Extramural research. 2012. Available at: http://epa.gov/ncer/rfa/archive/grants/01/kidscenter01.html. Accessed November 2, 2014.

- 26.US Environmental Protection Agency. Understanding the role of nonchemical stressors and developing analytic methods for cumulative risk assessments. Extramural research. 2009 Available at: http://epa.gov/ncer/rfa/2009/2009_star_cumulative_risk.html. Accessed November 2, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 27.US Environmental Protection Agency. Children’s Environmental Health and Disease Prevention Research Centers. Extramural research. 2012 Available at: http://grants.nih.gov/grants/guide/rfa-files/RFA-ES-12-001.html. Accessed November 2, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 28.US Environmental Protection Agency. Plan environmental justice 2014. 2011. Available at: http://www.epa.gov/environmentaljustice/resources/policy/plan-ej-2014/plan-ej-2011-09.pdf. Accessed November 2, 2014.

- 29.MacQueen KM, McLellan E, Metzger DS et al. What is community? An evidence-based definition for participatory public health. Am J Public Health. 2001;91(12):1929–1938. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.12.1929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.International RTI. Exhibit 3. CBPR requests for applications and peer review. Available at: http://www.rti.org/pubs/CBPR_req_app_peer_rev.pdf. Accessed November 4, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Green LW, George MA, Daniel M . Study of Participatory Research in Health Promotion: Review and Recommendations for the Development of Participatory Research in Health Promotion in Canada. Ottawa, Ontario: Royal Society of Canada; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cacari-Stone L, Wallerstein N, Garcia AP, Minkler M. The promise of community-based participatory research for health equity: a conceptual model for bridging evidence with policy. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(9):1615–1623. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.301961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Israel BA, Schulz AJ, Parker EA, Becker AB Community-Campus Partnerships for Health. Community-based participatory research: policy recommendations for promoting a partnership approach in health research. Educ Health (Abingdon) 2001;14(2):182–197. doi: 10.1080/13576280110051055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Horowitz CR, Robinson M, Seifer S. Community-based participatory research from the margin to the mainstream: are researchers prepared? Circulation. 2009;119(19):2633–2642. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.729863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities. Community Based Participatory Research Program. Available at: http://www.nimhd.nih.gov/our_programs/communityparticipationresearch.asp. Accessed November 4, 2014.

- 36.Strauss RP, Sengupta S, Quinn SC et al. The role of community advisory boards: involving communities in the informed consent process. Am J Public Health. 2001;91(12):1938–1943. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.12.1938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Newman SD, Andrews JO, Magwood GS, Jenkins C, Cox MJ, Williamson DC. Community advisory boards in community-based participatory research: a synthesis of best processes. Prev Chronic Dis. 2011;8(3):A70. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.George MA, Daniel M, Green LW. Appraising and funding participatory research in health promotion, 1998–99. Int Q Community Health Educ. 2006–2007;26(2):171–187. doi: 10.2190/R031-N661-H762-7015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Viswanathan M, Ammerman A, Eng E et al. Community-based participatory research: assessing the evidence: summary. Evid Rep Technol Assess (Summ) 2004;99:1–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.US Environmental Protection Agency. Science for sustainable and healthy tribes. Extramural research. Available at: http://www.epa.gov/ncer/rfa/2013/2013_star_tribal.html. Accessed November 2, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 41.US Environmental Protection Agency. Issues in tribal environmental research and health promotion: novel approaches for assessing and managing cumulative risks and impacts of global climate change. Extramural research. Available at: http://www.epa.gov/ncer/rfa/2006/2006_star_tribal.html. Accessed November 2, 2014. [Google Scholar]