Abstract

Background. Leaving the hospital against medical advice is an increasing problem in acute care settings and is associated with an array of negative health consequences that may lead to readmission for a worsened health outcome or mortality. Leaving the hospital against medical advice is particularly common among people who use illicit drugs (PWUD) and has been linked to a number of complex issues; however, few studies have focused specifically on this population beyond identifying them as being at an increased risk of leaving the hospital prematurely. Furthermore, programs and interventions for reducing the rate of leaving the hospital against medical advice among PWUD in acute care settings have not been well studied.

Objectives. We systematically assessed the literature examining hospital discharge against medical advice from acute care among this population and identified potential methods to minimize the occurrence of this phenomenon.

Search methods. We searched 5 electronic databases (from database inception to August 2014) and article reference lists for articles investigating hospital discharge from acute care against medical advice among PWUD. Search terms consistent across databases included “patient discharge,” “hospital discharge,” “against medical advice,” “drug user,” “substance-related disorders,” and “intravenous substance abuse.”

Selection criteria. Studies were eligible for inclusion if they were published in a peer-reviewed journal as an original research article in English. We excluded gray literature, case reports, case series, reviews, and editorials. We retained original studies that reported illicit drug use as a predictor of leaving the hospital against medical advice and studies of discharge against medical advice that included PWUD as a population of interest, and we assessed significance through appropriate statistical tests. We excluded studies that reported patients leaving the hospital against medical advice from psychiatric hospitals, drug treatment centers and emergency departments, and studies that discussed misuse of alcohol but not illicit drugs.

Data collection and analysis. We created an electronic database that included study abstracts and relevant information matching the keywords and search criteria. We reviewed potentially eligible articles independently by scanning the titles, abstracts, and full texts of articles after removing duplicates. We identified studies for which eligibility was unclear and decided which studies to include after thoroughly reviewing and discussing them.

Results. Of the 1649 studies that matched the search criteria, 17 met our inclusion criteria. Thirteen studies identified substance misuse as a significant predictor of leaving the hospital against medical advice. Three studies assessed the prevalence and predictors of leaving the hospital against medical advice among people who inject drugs and found that this phenomenon was commonly reported (prevalence range = 25%–30%). Factors positively associated with leaving the hospital against medical advice included recent injection drug use, Aboriginal ancestry, leaving on weekends and welfare check day. In-hospital methadone use, social support, older age, and admission to a community-based model of care were negatively associated with the outcome.

Conclusions. To better understand risk factors associated with leaving the hospital against medical advice among PWUD, future research should consider the effect of individual, social, and structural characteristics on leaving the hospital against medical advice among PWUD. The development and evaluation of novel methods to address interventions to reduce the rate of leaving the hospital prematurely is necessary.

PLAIN-LANGUAGE SUMMARY: Leaving the hospital against medical advice is common among people who use illicit drugs (PWUD) and has been linked to complex issues, including poor management of active addiction. We systematically assessed the literature examining hospital discharge against medical advice among PWUD and identified methods to potentially minimize the occurrence. We searched 5 electronic databases and article reference lists for articles investigating hospital discharge from acute care against medical advice among PWUD. We identified, screened, and selected studies using systematic methods. Seventeen met our inclusion criteria. Thirteen studies identified substance misuse as a significant predictor of leaving the hospital against medical advice. The prevalence of leaving the hospital against medical advice ranged from 25% to 30%. Factors positively associated with leaving the hospital against medical advice included recent injection drug use, Aboriginal ancestry, and leaving on weekends and welfare check day. In-hospital methadone use, social support, older age, and admission to a community-based model of care were negatively associated with the outcome. There is little evidence on factors associated with leaving the hospital against medical advice among PWUD and interventions to reduce the rate of leaving the hospital prematurely. Therefore, the development and evaluation of novel methods to address this issue are necessary.

Leaving the hospital against medical advice is an increasing problem in acute care settings and is linked to an array of negative health consequences. For instance, leaving the hospital against medical advice with an inadequately treated medical problem may result in increased morbidity and hospital readmission.1,2 A 2011 study demonstrated that patients who left the hospital against medical advice were 12 times more likely to be readmitted within 14 days with a related diagnosis than were patients who had a planned discharge.3

In addition, population-level data indicated the high risk of mortality among individuals who leave the hospital against medical advice,4 with a study showing that the odds of mortality of patients who left the hospital against medical advice doubled, even after adjusting for various confounders.2 Studies have also shown that leaving the hospital against medical advice introduces a huge financial burden on the health care system because these individuals fail to make a full recovery the first time they are treated, which necessitates readmission to a hospital.5,6

The literature on this subject has consistently shown that substance misuse is related to an increased risk of leaving the hospital against medical advice; however, the reason for this association remains unclear. Possible explanations for the high prevalence of hospital discharge against medical advice among people who use illicit drugs (PWUD) are thought to be complex and include stigma and discrimination in hospitals,7,8 the urge and need for PWUD to use drugs to sustain their addiction,9 and poor management of ongoing addiction and pain in these settings.10,11

From a population health perspective, leaving the hospital against medical advice is particularly concerning among the PWUD population because of the known health risks associated with illicit drug use, including injection-related soft tissue infections, infectious disease acquisition and progression, and other comorbidities.12–14 Furthermore, programs and interventions for reducing the rate of leaving the hospital prematurely among PWUD in acute care settings have not been well studied. Because of the gaps in information and the significant human suffering and health care costs associated with leaving the hospital against medical advice, there is a pressing need to better understand the full complexity of this issue.

We systematically assessed the literature that examined the prevalence and predictors of leaving the hospital against medical advice among PWUD and potential interventions to minimize this phenomenon. We searched 5 electronic databases and article reference lists for articles investigating hospital discharge from acute care against medical advice among PWUD. We identified, screened, and selected studies using systematic methods.

METHODS

We referred to the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) guidelines for the development of systematic reviews.15

Search Strategy

We searched the following 5 electronic databases to identify relevant studies published in peer-reviewed journals from database inception to August 2014: CINAHL, EMBASE, MEDLINE, PsycINFO, and Web of Science. Search terms consistent across databases included “patient discharge,” “hospital discharge,” “against medical advice,” “drug user,” “substance-related disorder,” and “intravenous substance abuse.”

We mapped the terms to database-specific subject headings and controlled vocabulary terms when available. When possible, we used methodological filters to exclude case reports and case series. We hand searched reference lists of published literature reviews and included studies. We restricted our search to English-language publications but did not restrict it with respect to year of publication.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Studies were eligible for inclusion if they were published in a peer-reviewed journal as an original research article. We excluded gray literature (e.g., unpublished literature, reports, theses, conference proceedings), case reports, case series, reviews, and editorials. We organized the criteria for considering studies using the population, intervention–exposure, comparison, outcome framework. We retained original studies that reported illicit drug use as a predictor of leaving the hospital against medical advice and studies of discharge against medical advice that included PWUD as a population of interest. Studies had to include analyses of factors associated with the outcome of interest, with significance assessed through appropriate statistical tests or the estimation of effect measures and confidence intervals (CIs) to be included in the analysis.

Because of our interest in patients who were hospitalized in acute care settings, we excluded studies that reported leaving the hospital against medical advice from psychiatric hospitals, drug treatment centers, and emergency departments. We also excluded studies if they discussed misuse of alcohol but not of illicit drugs.

Study Selection and Data Collection Process

We conducted the database search and entered study abstracts matching the keywords and search criteria into an electronic database. After removing duplicates, we independently reviewed potentially eligible articles by scanning the titles, abstracts, and full texts of articles. At each review stage, we excluded studies clearly not meeting the inclusion criteria from further review. We identified studies for which eligibility was unclear, and we made a final decision to include or exclude such studies after thorough review.

We extracted data for each eligible record using a standardized form that included information on study design, setting, sample size and characteristics, and major findings. We entered this information and reviewed it independently for accuracy and completeness.

RESULTS

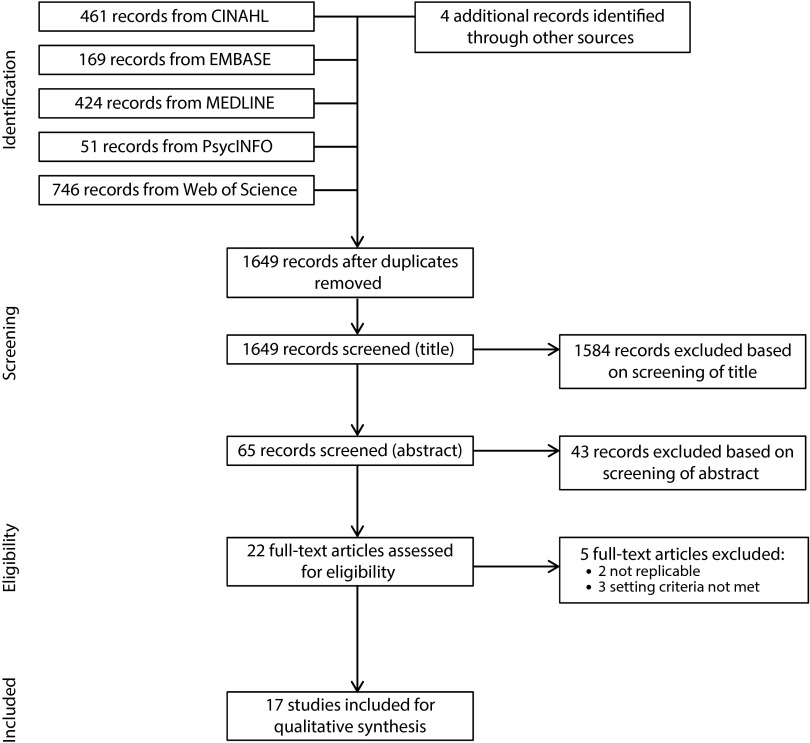

Database and hand searching yielded a total of 1649 potentially eligible studies (Figure 1). After initial title and abstract screenings, we removed 1627 studies from the analysis. Additionally, we excluded 5 studies following an assessment of the full text articles. Consistency was high between investigator searches, with only 2 differences in study eligibility reviewed. In total, 17 studies published between 1977 and 2014 met the eligibility criteria and we included them in the final qualitative synthesis. Included studies are presented in alphabetical order in Table 1.

FIGURE 1—

Flowchart of screening and article selection process: Australia, Canada, and United States, 1974–2011.

TABLE 1—

Summary of Included Studies: Australia, Canada, and United States, 1974–2011

| Author | Location | Study Design | Study Period | Sample Characteristics | Drug Use | Outcome | Main Findings |

| Aliyu16 | Baltimore, MD | Retrospective study | 2000 | 21 233 patient admissions (28.0% Black; 44.0% female) | 193 (0.9%) substance abuse–related diagnosis | 218 (1.0%) left the hospital AMA | Patients with a substance abuse–related diagnosis was a significant predictor of AMA discharge (20.0% vs 7.0%; P < .001) |

| Anis et al.17 | Vancouver, BC, Canada | Retrospective cohort study | 1997–1999 | 981 HIV-positive patients (median age: 38 y; 22.0% female) | 448 (46.0%) PWID | 125 (13.0%) left the hospital AMA | PWID patients was a significant predictor of AMA discharge (AOR = 4.13; 95% CI = 2.60, 6.57) |

| Chan et al.18 | Vancouver, BC, Canada | Retrospective cohort study | 1997–2000 | 480 HIV-positive PWID (1056 admissions; median age: 37 y; 31.0% female; 36.0% Aboriginal) | 100.0% (active PWID 641 [61.0%]) | 263 (24.9%) left the hospital AMA | Recent PWID (AOR = 2.07; 95% CI = 1.40, 3.06); Aboriginal (AOR = 1.59; 95% CI = 1.08, 2.34); weekends (AOR = 2.27; 95% CI = 1.49, 3.48); welfare check day (AOR = 2.95; 95% CI = 1.70, 5.10); in-hospital methadone (AOR = 0.49; 95% CI = 0.32, 0.77); social support (AOR = 0.34; 95% CI = 0.21, 0.53); older age per 10 y (AOR = 0.57; 95% CI = 0.44, 0.74) |

| Choi et al.3 | Vancouver, BC, Canada | Retrospective matched cohort study | January 2008–December 2008 | 656 hospitalized patients (2792 discharges; 36.0% female) | 254 (39.0%) PWID | 328 (50.0%, matched) left the hospital AMA | PWID was a significant predictor of AMA discharge (54.0% vs 23.0%; P < .001) |

| Fiscella et al.19 | New York, Florida, California | Cross-sectional study | 1998–2000 | 2 727 175 postpartum discharges (12.0% Black) | 27 272 (1.0%) drug abuse | 2727 (0.1%) left the hospital AMA | Drug dependence was the strongest risk factor for AMA discharge (AOR = 7.8; 95% CI = 6.6, 9.1) |

| Jafari et al.20 | Vancouver, BC, Canada | Mixed methods study | 2005–2009 | 165 clients admitted to CTCT with deep tissue infections (43.0% female; mean age = 41 y) | 139 (84.0%) PWUD; 65 (39.0%) PWID | 50 (30.0%) left the hospital AMA | Risk of leaving AMA was significantly lower among clients who were staying at CTCT (P < .001) |

| Jankowski and Drum21 | Boston, MA | Case–control study | 1974 | 248 hospitalized patients | 16 (6.5%) drug addiction | 73 (29.4%) left the hospital AMA | Drug addiction was a significant correlate of leaving the hospital AMA (22.0% vs 0.0%) |

| Kraut et al.22 | Manitoba, Canada | Retrospective study | 1990–2009 | 610 187 hospitalized patients (1 916 104 discharges) | 24 768 (1.3%) alcohol or drug abuse | 21 417 (1.1%) observations left the hospital AMA (2.1% individuals) | Drug abuse was a significant correlate of leaving the hospital AMA (AOR = 2.19; 95% CI = 1.99, 2.42) |

| Myers et al.23 | United States | Retrospective study | 1993–2005 | 581 380 patient admissions with cirrhosis (40.0% liver-related cirrhosis) | 13.0% drug abuse in DAMA group; 4.8% in non-DAMA | 16 509 (2.8%) left the hospital AMA | Drug abuse was a significant correlate of leaving the hospital AMA (AOR = 1.53; 95% CI = 1.44, 1.62) |

| Palepu et al.24 | Vancouver, BC, Canada | Case–control study | 1997–2000 | 262 hospitalized HIV-positive patients with pneumonia (27.0% female) | 138 (52.7%) PWID | 73 (27.9%) left the hospital AMA | No statistically significant interaction between DAMA × PWID on early readmission |

| Riddell and Riddell25 | Vancouver, BC, Canada | Retrospective study | 1996–2000 | 2432 hospitalized PWID (4760 admissions; 38.0% female; mean age = 35 y) | 100.0% | 26.4% left the hospital AMA | 16.0% increase in probability of leaving the hospital AMA on welfare Wednesday relative to other Wednesdays (P < .01) |

| Saitz26 | Massachusetts | Retrospective study | 1992 | 23 198 hospitalized patients with pneumonia (mean age = 68 y; 50.0% female; 92.0% White) | 3.0% drug-related diagnosis | 281 (1.2%) left the hospital AMA | Drug-related diagnosis was a significant correlate of leaving the hospital AMA (AOR = 2.5; 95% CI = 1.8, 3.4) |

| Seaborn Moyse and Osmun27 | Strathroy, ON, Canada | Retrospective cohort study | 2000–2002 | 6186 patient discharges | NR | 35 (0.6%) left the hospital AMA | Substance abuse was a significant correlate of leaving the hospital AMA (P < .001) |

| Smith and Telles28 | Philadelphia, PA | Retrospective study | 1986–1987 | 635 897 patient discharges (37.0% females left the hospital AMA) | 2025 (26.6%) alcohol or drug use or alcohol or drug-induced mental disorders among those DAMA | 7613 (1.2%) left the hospital AMA | Substance abuse and substance-induced organic mental disorders is associated with a 9.6% increase in % AMA discharges (P < .001) |

| Southern et al.2 | Bronx, NY | Retrospective cohort study | 2001–2008 | 84 080 general medical inpatient discharges (mean age = 58 y; 44.0% male; 35.0% Black) | 11 365 (13.5%) history of substance abuse | 3544 (4.2%) left the hospital AMA | History of substance abuse was significantly associated with leaving the hospital AMA (37.9% vs 12.4%; P < .001) |

| Tawk et al.29 | United States | Retrospective study | 1988–2006 | 4 499 760 patient discharges (61.0% female, weighted) | ∼17.0% AMA patients had drug dependence syndrome | 4 985 960 (0.9%, weighted) left the hospital AMA | Mental illness (including substance abuse) was a significant correlate of leaving the hospital AMA (AOR = 3.11; 95% CI = 2.98, 3.25) |

| Yong et al.30 | Adelaide, Australia | Retrospective study | 2002–2011 | 121 986 patient admissions (44.0% male) | NR | 1562 (1.3%) left the hospital AMA | Substance-related disorder was one of the most common principal diagnoses in the DAMA group |

Note. AMA = against medical advice; AOR = adjusted odds ratio; CI = confidence interval; CTCT = community transitional care team; DAMA = discharged against medical advice; NR = no response; PWID = people who inject drugs; PWUD = people who use illicit drugs.

Included Studies

Of the 17 included studies, all but 1 (in Australia) were conducted in Canada or the United States. Most studies employed retrospective study designs (n = 13), and few used case–control designs (n = 2), cross-sectional designs (n = 1), or mixed methods designs (n = 1). The majority of studies were conducted among general medical inpatients (n = 9). In addition, 3 studies were conducted specifically among people who inject drugs (PWID; including 1 study conducted among HIV-positive PWID), 2 studies were conducted among patients with pneumonia (including 1 study conducted among HIV-positive pneumonia patients), 1 study was conducted among HIV-positive patients, 1 study was conducted among patients with cirrhosis, and 1 study was conducted among female postpartum patients.

All studies relied on hospital administrative records for their outcome measure of leaving the hospital against medical advice. All studies relied on patient medical records and International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification31 codes to define their substance misuse variable. Substance misuse was inconsistently defined across studies, including such definitions as injection drug use status (n = 6), drug abuse or dependence (n = 5), alcohol or drug abuse or dependence (n = 5), and mental illness, including drug abuse, alcohol dependence, depression, and psychosis (n = 1).

Substance Misuse

Of the 5 studies that included drug abuse or dependence as a predictor of leaving the hospital against medical advice, 4 reported drug abuse as a significant and positive correlate of leaving the hospital against medical advice. These studies were conducted among general hospital inpatients (n = 610 187 patients),22 postpartum female patients (n = 2 727 175 discharges),19 patients with pneumonia (n = 23 198 patients),26 and patients with cirrhosis (n = 581 380 admissions).23 One study, conducted in Boston, Massachusetts, concluded that drug addiction was a significant correlate of leaving the hospital against medical advice; however, a test statistic to determine the strength of the association could not be calculated because 1 cell contained zero counts.21

Similarly, all 5 studies that examined alcohol or drug abuse or dependence as a predictor of leaving the hospital against medical advice among general hospital inpatients found them to be significant correlates of the outcome of leaving the hospital against medical advice.2,16,27,28,30 In a US national sample of adult patients who left hospitals between 1988 and 2006, 1 study found a positive and statistically significant association between mental illness diagnosis—which included drug abuse, alcohol dependence, depression, and psychosis—and leaving the hospital against medical advice. However, when patients with substance abuse diagnoses were removed from the mental illness variable, the adjusted odds ratio was attenuated.29

Three studies included injection drug use status as an explanatory variable of interest in their analyses examining potential correlates of leaving the hospital against medical advice. A retrospective matched cohort study conducted in Vancouver, Canada concluded that PWID were more likely to leave the hospital against medical advice (54%) than were their non–drug-using counterparts (23%).3 Similarly, Anis et al. reported that injection drug use was a significant predictor of leaving the hospital against medical advice among HIV-positive patients.17 Lastly, a study conducted by Palepu et al. found no statistically significant association between injection drug use and leaving the hospital against medical advice on early hospital readmission among HIV-positive pneumonia patients.24

Prevalence and Predictors

Three studies assessed the prevalence and various predictors of leaving the hospital against medical advice among PWID in Vancouver. Leaving the hospital against medical advice was commonly reported among PWID in the 3 studies, ranging from 25% to 30%.18,20,25 Analysis of a retrospective cohort study found that among HIV-positive PWID, recent injection drug use, Aboriginal ancestry, weekends, and welfare check day were positive correlates of leaving the hospital against medical advice, whereas in-hospital methadone use, social support, and older age were negatively associated with this outcome.18

Similarly, Riddell and Riddell indicated that there was a 16% increase in the probability of leaving the hospital against medical advice on “welfare Wednesdays” compared with any other Wednesday.25 In a retrospective study of PWID, Jafari et al. demonstrated that the risk of leaving the hospital against medical advice was significantly lower among clients admitted to the community transitional care team (a community care model of intravenous antibiotic therapy for PWID with deep tissue infection) than those who were admitted to the hospital.20

DISCUSSION

We found that there was consistency in the evidence presented by eligible studies, which was a positive association between substance misuse and leaving the hospital against medical advice among patients in acute care. A few studies explored the prevalence and predictors of leaving the hospital against medical advice among PWID specifically and found that a substantial proportion of PWID left the hospital against medical advice, with studies reporting a prevalence of up to 30% among this population.18,20 These studies also found that factors such as Aboriginal ancestry, recent injection drug use, and welfare check day were positively associated with the outcome.18,20 Moreover, the results of our review suggest that various mitigating factors—including in-hospital methadone use, social support, and a community model of care to treat PWID with deep tissue infections—have the potential to reduce the rate of leaving the hospital prematurely.

A small number of studies investigated various predictors of leaving the hospital against medical advice specifically among PWID. However, their data did not include any measurement of social or structural factors that might account for some of the explained variability in the effect of leaving the hospital against medical advice. For instance, previous studies have shown that having negative interactions with health care providers was associated with poor utilization of health care services and retention in care among PWUD.7,9 A qualitative study that was not included in our systematic review documented instances of both voluntary and involuntary discharges against medical advice because of negative cultural stereotypes in health care settings.9 Furthermore, a growing body of research has suggested that individuals who have been exposed to the criminal justice system are less likely to utilize health care services.32,33

Future studies should address the limitations of administrative data by linking routinely collected behavioral data with hospital and health service data sources (e.g., local hospital administrative databases, provincial or state health and drug insurance program databases) in an effort to provide a better understanding of the individual and contextual factors that influence leaving the hospital against medical advice among PWUD. Previous cohort studies that collected sociodemographic, behavioral, and contextual variables have been linked to emergency department databases to obtain information on health service use.34

The paucity of evidence regarding potential interventions to minimize hospital discharge against medical advice among PWUD warrants some attention. Because of the frequent occurrence of discharge against medical advice among PWUD, it is surprising that only 2 studies offered potential solutions for reducing the prevalence of premature hospital discharge for this population. Our systematic review is consistent with a narrative review that found a lack of evidence on how to effectively reduce the prevalence of leaving the hospital against medical advice among PWUD in acute care.6 Nevertheless, it is encouraging that 1 study included in our review observed a significant reduction in the rate of leaving against medical advice among patients in the community transitional care team program.20 This is a particularly valuable finding because PWID are most commonly hospitalized for cutaneous injection-related infections (e.g., cellulitis, abscess, osteomyelitis).35,36

Also of interest is the finding that in-hospital methadone use reduced hospital discharge against medical advice among HIV-positive PWID.18 The provision of methadone in hospital settings may address some of the issues related to underlying addictive behaviors and the wish to acquire more drugs.26 However, methadone maintenance therapy is only appropriate for opioid-dependent PWUD and may not apply to individuals who are dependent on other illicit substances. In addition, past studies have shown that many physicians do not prescribe adequate doses of methadone to hospitalized patients with opioid dependence,37,38 and as a result of opioid withdrawal from poor management of addiction and pain,10,37 many PWID may leave the hospital against medical advice.

Although beyond the scope of our systematic review, there is a much larger body of literature that discusses discharges against medical advice from psychiatric hospitals and drug treatment centers. Because of the overlap in patient characteristics between these settings and acute care hospitals, it may be valuable to draw on this literature to gain insights into strategies for preventing premature hospital discharge.

One effective strategy consistently reported in the psychiatric literature is the involvement of a patient advocate or psychiatric consultant who can proactively identify and address issues of substance misuse early during hospital admission.39,40 The incorporation of an addiction medicine component into medical training for all physicians may serve to build stronger relationships between physicians and patients with substance use disorders and consequently minimize discharge against medical advice among this population.41

Limitations

Limitations common to many of the included studies should be mentioned to better contextualize the findings.

First, the literature on substance misuse and leaving the hospital against medical advice is limited primarily to medical reviews and retrospective analyses. Thus, it is difficult to define a clear causal relationship between the explanatory variables and the outcome variable of interest. Future research of higher methodological quality is required to better understand the complex nature of substance misuse and leaving the hospital against medical advice. However, it is noteworthy that because of the unethical nature of randomizing patients to leave and not leave the hospital against medical advice, future studies will likely be restricted to observational study designs.

Second, analyses of medical reviews are limited by the available administrative data, which lack information on the dynamic nature of drug use behaviors and the broader social, structural, and environmental factors that may influence hospital discharges against medical advice.

Third, many of these studies were analyzed at the hospital admission or discharge level and did not take into account clustering among individual patients. As a result, these studies may have been more likely to falsely detect a significant difference that may have biased their findings.

Lastly, as a limitation of our review, it is possible that we missed some eligible studies in our search strategy. We recognize that the selection and qualitative synthesis of eligible studies is a subjective process; however, we sought to minimize this bias by duplicating our search and using 2 reviewers to conduct the screening procedure independently.

Conclusions

Our systematic review revealed that there is little evidence on risk factors associated with leaving the hospital against medical advice among PWUD. To better understand this phenomenon, future research is needed to consider the effect of individual, social, and structural characteristics on leaving the hospital against medical advice among this population. Because of the limited number of studies exploring interventions to reduce the rate of leaving the hospital prematurely among PWUD, the development and evaluation of novel methods to address this issue are necessary.

Acknowledgments

This review was funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (doctoral award GSD-134839 to L. T.).

The authors thank current and past British Columbia Centre for Excellence in HIV/AIDS researchers and staff for their assistance.

Human Participant Protection

Institutional review board approval was not needed because no human participants were involved in this study.

References

- 1.Weingart SN, Davis RB, Phillips RS. Patients discharged against medical advice from a general medicine service. J Gen Intern Med. 1998;13(8):568–571. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1998.00169.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Southern WN, Nahvi S, Arnsten JH. Increased risk of mortality and readmission among patients discharged against medical advice. Am J Med. 2012;125(6):594–602. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2011.12.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Choi M, Kim H, Qian H, Palepu A. Readmission rates of patients discharged against medical advice: a matched cohort study. PLoS One. 2011;6(9):e24459. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0024459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Glasgow JM, Vaughn-Sarrazin M, Kaboli PJ. Leaving against medical advice (AMA): risk of 30-day mortality and hospital readmission. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(9):926–929. doi: 10.1007/s11606-010-1371-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sclar DA, Robison LM. Hospital admission for schizophrenia and discharge against medical advice in the United States. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;12(2) doi: 10.4088/PCC.09m00827yel. pii:PCC.09m00827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alfandre DJ. “I’m going home”: discharges against medical advice. Mayo Clin Proc. 2009;84(3):255–260. doi: 10.4065/84.3.255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.van Boekel LC, Brouwers EPM, van Weeghel J, Garretsen HFL. Stigma among health professionals towards patients with substance use disorders and its consequences for healthcare delivery: systematic review. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013;131(1–2):23–35. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2013.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sayles JN, Wong MD, Kinsler JJ, Martins D, Cunningham WE. The association of stigma with self-reported access to medical care and antiretroviral therapy adherence in persons living with HIV/AIDS. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24(10):1101–1108. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-1068-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McNeil R, Small W, Wood E, Kerr T. Hospitals as a “risk environment”: an ethno-epidemiological study of voluntary and involuntary discharge from hospital against medical advice among people who inject drugs. Soc Sci Med. 2014;105:59–66. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.01.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huxtable CA, Roberts LJ, Somogyi AA, MacIntyre PE. Acute pain management in opioid-tolerant patients: a growing challenge. Anaesth Intensive Care. 2011;39(5):804–823. doi: 10.1177/0310057X1103900505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McCreaddie M, Lyons I, Watt D et al. Routines and rituals: a grounded theory of the pain management of drug users in acute care settings. J Clin Nurs. 2010;19(19–20):2730–2740. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2010.03284.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Binswanger IA, Kral AH, Bluthenthal RN, Rybold DJ, Edlin BR. High prevalence of abscesses and cellulitis among community-recruited injection drug users in San Francisco. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;30(3):579–581. doi: 10.1086/313703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lloyd-Smith E, Kerr T, Hogg RS, Li K, Montaner JS, Wood E. Prevalence and correlates of abscesses among a cohort of injection drug users. Harm Reduct J. 2005;2:24. doi: 10.1186/1477-7517-2-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.de Sá LC, de Araújo TME, Griep RH, Campelo V, Monteiro CF de S. Seroprevalence of hepatitis C and factors associated with this in crack users. Rev Lat Am Enfermagem. 2013;21(6):1195–1202. doi: 10.1590/0104-1169.3126.2354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ. 2009;339 b2535. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Aliyu ZY. Discharge against medical advice: sociodemographic, clinical and financial perspectives. Int J Clin Pract. 2002;56(5):325–327. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Anis AH, Sun H, Guh DP, Palepu A, Schechter MT, O’Shaughnessy MV. Leaving hospital against medical advice among HIV-positive patients. CMAJ. 2002;167(6):633–637. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chan AC, Palepu A, Guh DP et al. HIV-positive injection drug users who leave the hospital against medical advice: the mitigating role of methadone and social support. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2004;35(1):56–59. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200401010-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fiscella K, Meldrum S, Franks P. Post partum discharge against medical advice: who leaves and does it matter? Matern Child Health J. 2007;11(5):431–436. doi: 10.1007/s10995-007-0194-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jafari S, Joe R, Elliot D, Nagji A, Hayden S, Marsh DC. A community care model of intravenous antibiotic therapy for injection drug users with deep tissue infection for “reduce leaving against medical advice.”. Int J Ment Health Addict. 2015;13:49–58. doi: 10.1007/s11469-014-9511-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jankowski CB, Drum DE. Diagnostic correlates of discharge against medical advice. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1977;34(2):153–155. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1977.01770140043004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kraut A, Fransoo R, Olafson K, Ramsey CD, Yogendran M, Garland A. A population-based analysis of leaving the hospital against medical advice: incidence and associated variables. BMC Health Serv Res. 2013;13(1):415. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-13-415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Myers RP, Shaheen AAM, Hubbard JN, Kaplan GG. Characteristics of patients with cirrhosis who are discharged from the hospital against medical advice. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7(7):786–792. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2009.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Palepu A, Sun H, Kuyper L, Schechter MT, O’Shaughnessy MV, Anis AH. Predictors of early hospital readmission in HIV-infected patients with pneumonia. J Gen Intern Med. 2003;18(4):242–247. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2003.20720.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Riddell C, Riddell R. Welfare checks, drug consumption, and health: evidence from Vancouver injection drug users. J Hum Resour. 2006;41(1):138–161. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Saitz R. Discharges against medical advice: time to address the causes. CMAJ. 2002;167(6):647–648. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Seaborn Moyse H, Osmun WE. Discharges against medical advice: a community hospital’s experience. Can J Rural Med. 2004;9(3):148–153. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Smith DB, Telles JL. Discharges against medical advice at regional acute care hospitals. Am J Public Health. 1991;81(2):212–215. doi: 10.2105/ajph.81.2.212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tawk R, Freels S, Mullner R. Associations of mental, and medical illnesses with against medical advice discharges: the National Hospital Discharge Survey, 1988–2006. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2013;40(2):124–132. doi: 10.1007/s10488-011-0382-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yong TY, Fok JS, Hakendorf P, Ben-Tovim D, Thompson CH, Li JY. Characteristics and outcomes of discharges against medical advice among hospitalized patients. Intern Med J. 2013;43(7):798–802. doi: 10.1111/imj.12109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 32.van Olphen J, Freudenberg N, Fortin P, Galea S. Community reentry: perceptions of people with substance use problems returning home from New York City jails. J Urban. 2006;83(3):372–381. doi: 10.1007/s11524-006-9047-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.van Olphen J, Eliason MJ, Freudenberg N, Barnes M. Nowhere to go: how stigma limits the options of female drug users after release from jail. Subst Abuse Treat Prev Policy. 2009;4(1):10. doi: 10.1186/1747-597X-4-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lloyd-Smith E, Tyndall M, Zhang R et al. Determinants of cutaneous injection-related infections among injection drug users at an emergency department. Open Infect Dis J. 2012;6 doi: 10.2174/1874279301206010005. pii:80176398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lloyd-Smith E, Wood E, Zhang R et al. Determinants of hospitalization for a cutaneous injection-related infection among injection drug users: a cohort study. BMC Public Health. 2010;10:327. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-10-327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Palepu A, Tyndall MW, Leon H et al. Hospital utilization and costs in a cohort of injection drug users. CMAJ. 2001;165(4):415–420. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hines S, Theodorou S, Williamson A, Fong D, Curry K. Management of acute pain in methadone maintenance therapy in-patients. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2008;27(5):519–523. doi: 10.1080/09595230802245519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Woody GE, McLellan AT, O’Brien CP, Luborsky L. Addressing psychiatric comorbidity. NIDA Res Monogr. 1991;106:152–166. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Targum SD, Capodanno AE, Hoffman HA, Foudraine C. An intervention to reduce the rate of hospital discharges against medical advice. Am J Psychiatry. 1982;139(5):657–659. doi: 10.1176/ajp.139.5.657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Holden P, Vogtsberger KN, Mohl PC, Fuller DS. Patients who leave the hospital against medical advice: the role of the psychiatric consultant. Psychosomatics. 1989;30(4):396–404. doi: 10.1016/S0033-3182(89)72245-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wood E, Samet JH, Volkow ND. Physician education in addiction medicine. JAMA. 2013;310(16):1673–1674. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.280377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]