Abstract

Objectives. We compared severe maternal morbidity (SMM) and SMM subtypes, including HIV, of refugee women with those of nonrefugee immigrant and nonimmigrant women.

Methods. We linked 1 154 421 Ontario hospital deliveries (2002–2011) to immigration records (1985–2010) to determine the incidence of an SMM composite indicator and its subtypes. We determined SMM incidence according to immigration periods, which were characterized by lifting restrictions for all HIV-positive immigrants (in 1991) and refugees who may place “excessive demand” on government services (in 2002).

Results. Refugees had a higher risk of SMM (17.1 per 1000 deliveries) than did immigrants (12.1 per 1000) and nonimmigrants (12.4 per 1000). Among SMM subtypes, refugees had a much higher risk of HIV than did immigrants (risk ratio [RR] = 7.94; 95% confidence interval [CI] = 5.64, 11.18) and nonimmigrants (RR = 17.37; 95% CI = 12.83, 23.53). SMM disparities were greatest after the 2002 policy came into effect. After exclusion of HIV cases, SMM disparities disappeared.

Conclusions. An apparent higher risk of SMM among refugee women in Ontario, Canada is explained by their high prevalence of HIV, which increased over time parallel to admission policy changes favoring humanitarian protection.

As of mid-2014, approximately 18 million refugees were of concern to the United Nations (UN) High Commissioner for Refugees and the UN Relief and Works Agency (which is responsible for Palestinian refugees).1,2 These persons feared persecution or violence because of their race, religion, nationality, or political views and were forced to flee their home countries.3

REFUGEE AND NONREFUGEE IMMIGRATION TO CANADA

Under Canada’s international obligations pursuant to the 1951 UN Convention and the 1967 Protocol Relating to the Status of Refugees, 750 000 refugees became permanent residents in Canada between 1989 and 2013, which is approximately 10% of all permanent residents admitted annually.4 The majority of refugees arrived in Canada’s most populous province, Ontario.5 Refugees to Canada originated from Africa and the Middle East (38%), Asia and the Pacific (33%), South and Central America (18%), Europe (8%), and the United States (2%).5

“Sponsored” and “nonsponsored” refugees are admitted in approximately equal numbers. Sponsored refugees are chosen abroad, usually from refugee camps administered by the UN High Commissioner for Refugees, are particularly vulnerable (e.g., women and girls at risk), and face no timely durable solution to exile.6 Sponsored refugees are either “convention refugees” (meeting the 1951 UN Convention definition) or in “refugeelike situations” and arrive in Canada with the support of the government or a private organization.7 Sponsored refugees become permanent residents on arrival. Nonsponsored refugees (“refugee claimants” or “asylum seekers”) arrive in Canada using personal resources, often under precarious circumstances, and claim asylum. The Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada, a quasijudicial tribunal, conducts admissibility hearings and grants permanent residency to nonsponsored refugees who demonstrate that they meet the definition of a convention refugee or a “person in need of protection.”8

In the past 3 decades, immigration to Canada has been driven primarily by economic considerations.9 A points system, in which applicants exceeding a specified threshold of points on the basis of categories including education, language fluency, and work experience, has been used to screen applications for permanent residency.10 Family members of Canadian citizens or permanent residents who do not qualify as economic immigrants can apply through the “family class.”11 Between 1989 and 2013, 55% of permanent residents to Canada were economic immigrants4 and 30% were family class immigrants.4 These immigrants originate from Asia and the Pacific (52%), Africa and the Middle East (19%), Europe (17%), South and Central America (8%), and the United States (4%).5

POTENTIAL FOR HEALTH DIFFERENCES BETWEEN REFUGEES AND OTHER IMMIGRANTS

On the surface, it might appear that exposure to premigration health determinants (e.g., limited or no access to health care) and experiences (e.g., political unrest) would be similar for all immigrants originating from the same country. However, specific admission criteria for economic immigration and relationships with Canadian citizens or permanent residents among family class immigrants may result in health determinant advantages, both before (e.g., education, employment) and after migration (e.g., socioeconomic position). Conversely, refugee status is founded on persecution by social characteristics (e.g., religion, race), which may be strongly associated with long-standing health disadvantages, such as poor nutritional status,12 reduced access to sexual and reproductive and other health services,13 and limited education.14 Thus, refugees may possess a unique set of health determinants that are systematically different from those of their nonrefugee immigrant counterparts. Because of these differences, the healthy immigrant effect (whereby at arrival immigrants are healthier than are their native-born counterparts) may not apply to refugees.15

Studies examining diverse maternal health outcomes among immigrant subpopulations (including large numbers of refugees) in the United States16,17 and Norway18 and among refugee subpopulations in Canada19 both support16 and oppose17–19 the healthy immigrant effect among refugees. Another study found a decreased risk of requiring an emergency cesarean delivery among refugees and asylum seekers compared with immigrants in Canada20 but could not assess the healthy immigrant effect because of the lack of a native-born comparator.

Severe maternal morbidity (SMM), or near miss morbidity, has become an increasingly important indicator to assess both the maternal health of populations21–23 and the quality of obstetric care,24 particularly in high-income countries, where maternal mortality is too rare to be informative. Although SMM lacks a standard international definition, a case has been defined as “a woman who nearly died but survived a complication that occurred during pregnancy, childbirth or within 42 days of termination of pregnancy.”24(p294) Because numerous and rare complications can contribute to SMM, it is measured as a composite index. Restricted access to and poor quality of sexual and reproductive health care in underresourced emergency settings13 before refugee arrival may aggravate SMM. We therefore hypothesized that refugees would be at a higher risk of SMM than would other immigrants and nonimmigrants.

Immigration policies may also influence the maternal health status of refugees and immigrants. Policies for HIV-positive immigration applicants have evolved in both the United States25,26 and Canada. In Canada, by 1991, well-managed HIV was deemed not to pose a threat to public health and safety. Consequently, all HIV-positive immigration applicants were permitted entry into Canada provided that they would not surpass an “excessive demand” threshold, defined as the per capita cost of health and social services over 5 consecutive years for an average Canadian.27 Informally, rejecting refugees with HIV was deemed to run contrary to the government’s humanitarian objectives.25 Because HIV infection in pregnancy has been shown to increase the risk of direct obstetric complications, such as puerperal sepsis and antepartum hemorrhage,28 this policy may have resulted in greater maternal comorbidities among those immigrating after 1991.

The Immigration and Refugee Protection Act (IRPA) of 2002 acknowledges the Convention Against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (1984), thus expanding refugee protection to include those at risk for torture or cruel and unusual treatment (persons in need of protection).10 The IRPA also prioritized humanitarian protection (i.e., convention refugees, persons in refugeelike situations, and persons in need of protection) for refugee immigration and formally exempted refugees from inadmissibility on the basis of excessive demand.10 Because of these changes to Canadian immigration policies, we hypothesized that the risk of SMM (specifically the HIV subtype and related comorbidities) would (1) increase with recency of immigration and (2) be higher for refugees compared with other immigrants arriving after IRPA was enacted.

We used a Canadian-specific SMM surveillance indicator29 and its subtypes to compare the maternal health of refugees (both sponsored and nonsponsored permanent residents) with other immigrants and nonimmigrants in Ontario, Canada. We also examined whether changes in Canadian government immigrant health admission policies influenced disparities in SMM.

METHODS

This population-based database study included all Ontario hospital admissions for childbirth that occurred between April 1, 2002 and March 31, 2011. We identified deliveries to refugees and immigrants retrospectively through linkage to the Citizenship and Immigration Canada Permanent Resident Database, which includes all immigrants who obtained permanent residency between 1985 and 2010. We attributed deliveries not linked to the database to nonimmigrants, most of whom were Canadian born.

Because the social and cultural conditions to which women are exposed before reaching reproductive age have an important effect on maternal outcomes later in life, we excluded refugees and immigrants younger than 15 years at the date of becoming permanent residents, eliminating the mixed effects resulting from exposure to both foreign and Canadian social and cultural environments before reproductive age. To ensure comparability, we also excluded nonimmigrants who were younger than 15 years at the time of delivery.

All women were eligible for universal, publicly funded health care. The unit of analysis was the delivery episode, in which we counted multiple births as a single delivery.

Data Sources

We linked 2 administrative databases held at the Institute for Clinical and Evaluative Sciences in Toronto, Ontario. We obtained records for women admitted to an Ontario hospital for childbirth from the Discharge Abstract Database, which originates from the Canadian Institute of Health Information. We used diagnosis and procedure codes (from International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision: Canadian Enhancement [ICD-10-CA]30 and Canadian Classification of Health Interventions [CCI]31) to identify women who had any SMM.29 This data set also contained information on maternal age at the time of delivery, self-reported parity, and birth plurality.

The Canadian government administers the Citizenship and Immigration Canada Permanent Resident Database, which contains information on refugee status and other characteristics as described in Table 1. Less than 1% of records in the database contained missing values.

TABLE 1—

Maternal Characteristics: Ontario, Canada, 2002–2011

| Characteristic | Refugees (n = 30 581), No. (%) | Immigrants (n = 236 565), No. (%) | Nonimmigrants (n = 886 975), No. (%) |

| Age at delivery, y | |||

| 15–19 | 283 (0.9) | 1 085 (0.5) | 40 993 (4.6) |

| 20–24 | 2 930 (9.6) | 22 729 (9.6) | 127 594 (14.4) |

| 25–29 | 7 862 (25.7) | 69 132 (29.2) | 245 239 (27.7) |

| 30–34 | 10 491 (34.3) | 84 127 (35.6) | 298 500 (33.7) |

| 35–39 | 7 034 (23.0) | 48 382 (20.5) | 146 354 (16.5) |

| ≥ 40 | 1 981 (6.5) | 11 110 (4.7) | 28 385 (3.2) |

| Parity (previous births) | |||

| 0 | 9 638 (31.6) | 100 713 (42.6) | 408 189 (46.1) |

| 1 | 9 930 (32.5) | 90 063 (38.1) | 311 950 (35.2) |

| 2 | 5 719 (18.7) | 31 682 (13.4) | 114 163 (12.9) |

| ≥ 3 | 5 258 (17.2) | 13 870 (5.9) | 51 414 (5.8) |

| Plurality | |||

| Singleton | 30 275 (98.5) | 234 199 (98.6) | 869 235 (98.2) |

| Higher order | 461 (1.5) | 3 305 (1.4) | 16 217 (1.8) |

| Language ability at arrival | |||

| English | 17 880 (58.5) | 139 973 (59.2) | NA |

| French | 777 (2.5) | 2 493 (1.1) | |

| Both English and French | 639 (2.1) | 6 933 (2.9) | |

| Neither English nor French | 11 285 (36.9) | 87 161 (36.9) | |

| Education level at arrival | |||

| 0–9, y | 8 979 (29.4) | 32 293 (13.7) | NA |

| 10–12, y | 11 525 (37.7) | 57 661 (24.4) | |

| ≥13,a y | 3 372 (11.0) | 25 935 (10.9) | |

| Trade certificate, no university diploma | 3 909 (12.8) | 32 907 (13.9) | |

| Bachelor’s, master’s, or doctorate | 2 796 (9.1) | 87 769 (37.1) | |

| Region of maternal birth | |||

| Africa | 9 175 (30.0) | 16 270 (6.9) | NA |

| Asia and Oceania Islands | 14 267 (46.7) | 159 779 (67.6) | |

| Industrialized countriesb | 120 (0.0) | 11 409 (4.9) | |

| Latin America and Caribbean | 3 113 (10.2) | 26 563 (11.2) | |

| Southern and Eastern Europe | 3 901 (12.8) | 22 462 (9.5) | |

| Immigration year grouping | |||

| 1985–1990 | 1 736 (5.7) | 7 613 (3.2) | NA |

| 1991–2001 | 14 901 (48.7) | 109 880 (46.5) | |

| 2002–2010 | 13 994 (45.6) | 119 072 (50.3) | |

| Duration of residence at delivery, y | |||

| ≤ 4c | 14 621 (47.8) | 130 734 (55.3) | NA |

| 5–9 | 8 407 (27.5) | 67 006 (28.3) | |

| 10–14 | 5 506 (18.0) | 28 961 (12.2) | |

| ≥ 15 | 2 045 (6.7) | 9 859 (4.2) |

Note. NA = not applicable. Table shows deliveries that occurred 2002–2011.

≥ aged 13 y category does not include other categories.

Industrialized countries are those in North America, Western and Northern Europe, Australia, and New Zealand.

≤ 4 category includes a small proportion of women who delivered before receiving permanent residency and before they were eligible for the Ontario Health Insurance Plan.

Variables

We measured the health outcome of interest, SMM, by a composite surveillance indicator,22,29 which the Canadian Perinatal Health Surveillance System developed. We operationalized the SMM indicator as any woman having 1 or more of the 45 ICD-10-CA and CCI diagnoses or procedures related to specific diseases (e.g., HIV), interventions (e.g., blood transfusion), or organ dysfunctions (e.g., hepatic failure) reported during hospital admission for labor or delivery.29 The majority of these codes are incident conditions or interventions arising during delivery, but a few specify prevalent, preexisting conditions. A study examining the validity of perinatal data available in the Discharge Abstract Database suggested that both diagnoses and procedures are accurately coded and supported the use of this database for perinatal research.32

The exposure of interest was refugee status compared with other immigrants and with nonimmigrants.

We identified potential confounders a priori and included them as fixed effects. Some confounders were available for all deliveries, including maternal age measured at delivery, parity, and plurality. Other confounders were available only for refugees and other immigrants because this information was collected by Citizenship and Immigration Canada. These included maternal country of birth, categorized into world subregion and world region according to the UN classification system33; maternal education at arrival; knowledge of official Canadian languages; and duration of residence in Canada, defined as the time (in years) elapsed between the date of becoming a permanent resident and the date of delivery.

Analytic Methods

We reported the probability of any SMM and SMM subtypes as risks (SMM cases per 1000 deliveries), keeping in mind that the term “risk” (implying new cases) is used liberally because fewer than 5 SMM subtypes specify prevalent conditions (e.g., preexisting hypertensive heart disease). To assess the disparities in SMM subtypes between refugees and immigrants and between refugees and nonimmigrants, we used log-binomial regression models to calculate unadjusted risk ratios (RRs) and 99% confidence intervals (CIs).

Because of the numerous SMM subtypes, we estimated more conservative 99% CIs to account for multiple hypothesis testing and to compensate for increased chances of a type 1 error. We also calculated unadjusted and adjusted RRs (ARRs) and 95% CIs for any SMM, SMM excluding all deliveries with asymptomatic HIV (ICD-10-CA code Z21), and SMM excluding all deliveries with HIV. When comparing refugees to nonimmigrants (model 1), we adjusted ARRs for maternal age and parity. When comparing refugees to other immigrants (model 2), unadjusted models included a random intercept for country of birth to take into account the potential similarity of SMM among immigrants from the same country of birth. Model 2 ARRs included all potential confounders.

To examine the impact of changes in immigration policy on SMM, we stratified model 2 by periods of immigration. First, we stratified analyses before and after 1991, when HIV/AIDS was removed as grounds for rejecting any immigration applicant.25 We stratified a second time before and after removal of the excessive demand policy for refugee admission in 2002 (enacted by the IRPA). We used the Cochran–Armitage test to examine linear trends in unadjusted SMM risks across periods of immigration for refugees and other immigrants. We also conducted a linear test for trend for SMM adjusted risk ratios across years of immigration.

RESULTS

Descriptive characteristics of the study population are summarized in Table 1.

Of all SMM subtypes (Table A, available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org), HIV had the highest RR, at RR = 7.94 (99% CI = 5.64, 11.18) and RR = 17.37 (99% CI = 12.83, 23.53), respectively. RRs for both asymptomatic HIV (ICD-10-CA code Z21) and unspecified HIV with manifestations of AIDS (ICD-10-CA code B24) were similar in magnitude to all HIV. Refugees also had a higher risk of blood transfusion (RR = 1.22; 99% CI = 1.01, 1.46) than did immigrants and a higher risk of embolization and ligation of pelvic vessels with postpartum hemorrhage (RR = 1.93; 99% CI = 1.18, 3.13) than did nonimmigrants. Cerebral edema and disseminated intravascular coagulation were also more prevalent among refugees than among nonimmigrants, but this finding should be interpreted with caution because there were 6 or fewer cases among refugees.

After adjustment (Table 2), the risk of any SMM remained significantly higher among refugees than among nonimmigrants (model 1: ARR = 1.34; 95% CI = 1.23, 1.47) and other immigrants (model 2: ARR = 1.22; 95% CI = 1.09, 1.36). When we excluded deliveries with asymptomatic HIV, leaving those with unspecified HIV with manifestations of AIDS (henceforth referred to as unspecified HIV/AIDS), the associations were reduced and remained marginally significant: ARR = 1.14 (95% CI = 1.04, 1.26; vs nonimmigrants) and ARR = 1.16 (95% CI = 1.03, 1.30; vs immigrants). When we further excluded all deliveries with HIV, the associations became nonsignificant: ARR = 1.07 (95% CI = 0.97, 1.18; vs nonimmigrants) and ARR = 1.11 (95% CI = 0.99, 1.35; vs immigrants).

TABLE 2—

Any SMM, SMM Excluding Deliveries With Asymptomatic HIV, and SMM Excluding Deliveries With All HIV of Refugees Compared With Nonimmigrants (Model 1) and Refugees Compared With Immigrants (Model 2): Ontario, Canada, 2002–2011

| Model 1 |

Model 2 |

||||

| SMM | Refugees | Immigrants | Nonimmigrants | Refugees | Immigrants |

| Any | |||||

| No. of deliveries | 30 420 | 235 545 | 878 709 | 30 420 | 235 540 |

| No. of cases (risk/1000 deliveries) | 519 (17.1) | 2856 (12.1) | 10 878 (12.4) | 519 (17.1) | 2875 (12.2) |

| RR (95% CI) | 1.38 (1.26, 1.50) | 0.98 (0.94, 1.02) | 1.00 (Ref) | 1.25 (1.12, 1.39) | 1.00 (Ref) |

| ARR (95% CI) | 1.34 (1.23, 1.47) | 0.97 (0.93, 1.01) | 1.00 (Ref) | 1.22 (1.09, 1.36) | 1.00 (Ref) |

| Excluding deliveries with asymptomatic HIV/AIDS | |||||

| No. of deliveries | 30 335 | 235 461 | 878 575 | 30 335 | 235 456 |

| No. of cases (risk/1000 deliveries) | 434 (14.3) | 2772 (11.8) | 10 744 (12.2) | 434 (14.3) | 2772 (11.8) |

| RR (95% CI) | 1.17 (1.06, 1.29) | 0.96 (0.92, 1.00) | 1.00 (Ref) | 1.17 (1.05, 1.31) | 1.00 (Ref) |

| ARR (95% CI) | 1.14 (1.04, 1.26) | 0.96 (0.92, 1.00) | 1.00 (Ref) | 1.16 (1.03, 1.30) | 1.00 (Ref) |

| Excluding deliveries with all HIV disease (asymptomatic and unspecified HIV/AIDS) | |||||

| No. of deliveries | 30 305 | 235 433 | 878 525 | 30 305 | 235 428 |

| No. of cases (risk/1000 deliveries) | 404 (13.3) | 2744 (11.7) | 10 694 (12.2) | 404 (13.3) | 2744 (11.7) |

| RR (95% CI) | 1.09 (0.99, 1.21) | 0.96 (0.92, 1.00) | 1.00 (Ref) | 1.13 (1.01, 1.27) | 1.00 (Ref) |

| ARR (95% CI) | 1.07 (0.97, 1.18) | 0.95 (0.91, 0.99) | 1.00 (Ref) | 1.11 (0.99, 1.25) | 1.00 (Ref) |

Note. ARR = adjusted risk ratio; CI = confidence interval; RR = unadjusted risk ratio; SMM = severe maternal morbidity. Table shows deliveries that occurred 2002–2011. RRs: model 1 does not include a random intercept; model 2 includes a random intercept for maternal country of birth. ARRs: model 1 includes adjustment for maternal age at delivery (15–19, 20–24, 25–29, 30–34, 35–39, ≥ 40 y) and parity (0, 1, 2, ≥ 3 previous births); model 2 includes a random intercept for maternal country of birth, and fixed effects include adjustment for maternal age at delivery (15–19, 20–24, 25–29, 30–34, 35–39, ≥ 40 y), parity (0, 1, 2, ≥ 3 previous births), education level (0–9, 10–12, ≥ 13 y, trade certificate or no university diploma, bachelor’s, master’s, or doctorate degree), language ability (1 or both of English and French or neither), and duration of residence (in years).

Because asymptomatic HIV suggests that the disease has not progressed to AIDS, we further descriptively examined only those with unspecified HIV/AIDS (30, 28, and 55 deliveries to refugees, immigrants, and nonimmigrants, respectively). For 51% of these deliveries, unspecified HIV/AIDS was described as a preadmission comorbidity, for 5 or fewer of these deliveries it was described as the most responsible diagnosis, and for the remaining cases HIV/AIDS was classified as a secondary diagnosis. No particular most responsible diagnosis or group of related diagnoses was in excess among refugees for deliveries with unspecified HIV/AIDS classified as either a comorbidity or a secondary diagnosis. Furthermore, there were very few obvious AIDS manifestations diagnoses34 (e.g., infectious or viral diseases) and none in excess among deliveries to refugees.

We examined SMM subtypes among those deliveries with unspecified HIV/AIDS, and 5 or fewer deliveries in each group exhibited 1 or more other SMM subtypes. Although cesarean delivery is recommended for severe HIV,35 there was also no significant difference in the proportion of cesarean deliveries between exposure groups (P = .385).

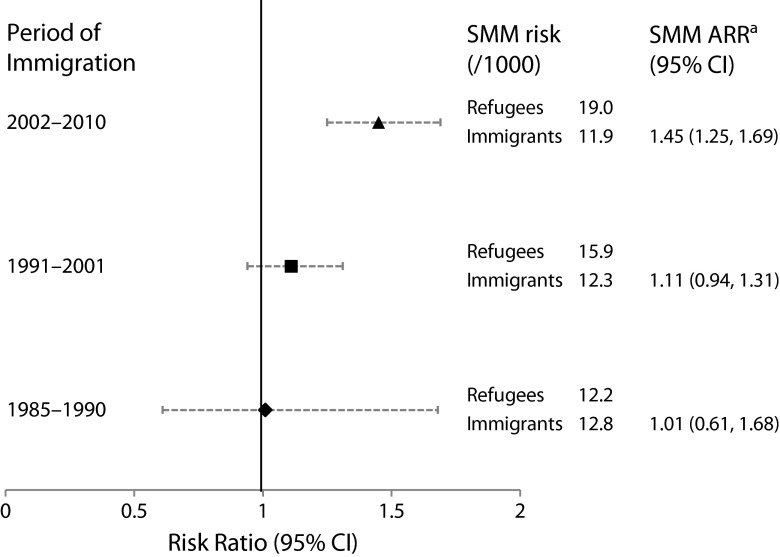

SMM risk among refugees was positively associated with recency of immigration (1985–1990: 12.2; 1991–2001: 15.9; 2002–2010: 19.0 per 1000 deliveries; P < .01; Figure 1). We did not observe any trend among other immigrants (12.8, 12.3, and 11.9 per 1000 deliveries; P = .25). Refugees who became permanent residents after IRPA came into effect (2002 onward) experienced a 45% greater risk of any SMM compared with immigrants over the same period (ARR = 1.45; 95% CI = 1.25, 1.69; Figure 1). This disparity was greater than was that for those admitted between 1991 and 2001 (ARR = 1.11; 95% CI = 0.94, 1.40) and 1985 and 1990 (ARR = 1.01; 95% CI = 0.61, 1.68). The linear test for trend in SMM adjusted risk ratios across immigration years was significant (P = .02). When we excluded deliveries with HIV, SMM risk was reduced and no longer significantly elevated after 2002 (ARR = 1.12; 95% CI = 0.94, 1.33; not shown).

FIGURE 1—

Comparison of refugee with other immigrant SMM by periods of immigration: Ontario, Canada, 2002–2011.

Note. ARR = adjusted risk ratio; CI = confidence interval; SMM = severe maternal morbidity. Figure shows deliveries that occurred 2002–2011. P for trend = .02.

aARRs include a random intercept for maternal country of birth and fixed effects include adjustment for maternal age at delivery (15–19, 20–24, 25–29, 30–34, 35–39, ≥ 40 years), parity (0, 1, 2, ≥ 3 previous births), education level (0–9 years, 10–12 years, ≥ 13 years, trade certificate/nonuniversity diploma, bachelor’s/master’s/doctorate), language ability (1 or both of English and French, neither), and duration of residence (years).

DISCUSSION

We found that the risk of SMM and its subtype HIV were significantly higher among refugees than among immigrants and nonimmigrants. However, once we excluded deliveries of women with HIV, SMM risk was no longer significantly elevated among refugees compared with other groups, suggesting that HIV was the primary cause of increased SMM risk among refugees. Among deliveries with unspecified HIV/AIDS, refugees did not appear to be at greater risk of AIDS manifestations, other SMM subtypes, or related specific most responsible diagnoses. This finding should be interpreted with caution because of both the small number of deliveries with unspecified HIV/AIDS in all groups (< 60) and the possible underascertainment of AIDS manifestations, individual SMM subtypes, and other noted diagnoses in the hospitalizations data. Considering these cautions, the findings suggest that refugees with HIV did not place increased demand on the health care system at the time of delivery.

In addition, we found that changes in Canadian immigration policies were important drivers of the overall trends in SMM risk seen among refugee and immigrant women. The disparity in SMM between refugees and other immigrants was significant for those admitted after IRPA was enacted in 2002, suggesting that this policy was successful in shifting the emphasis of refugee immigration toward increased humanitarian protection.

In 2011, 69.0% of the global burden of HIV/AIDS was in sub-Saharan Africa36; so it is unsurprising that 82.0% of the deliveries to immigrants with HIV in our study were to women from this region. Across Canada between 1984 and 2010, 17.9% of African-born mothers with HIV had infants with confirmed HIV infection, compared with 12.7% among North American–born mothers.37 This suggests that additional work may be needed to address the challenges African-born women with HIV/AIDS experience38 before and during pregnancy. The refugee status of these women may further complicate appropriate responses.

To our knowledge, SMM risk among refugees or other immigrants in the United States has not been studied. Some studies have looked at SMM among asylum seekers and immigrants in other countries, using different definitions of SMM than we used, none of which included HIV. A Dutch study examining severe acute maternal morbidity among asylum seekers (not permanent residents at the time of their study) found a 3.6 times greater risk of severe acute maternal morbidity than that of non-Western immigrants and 4.5 times greater risk than that in the general Dutch population.38 The study also noted that among those with severe acute maternal morbidity, the prevalence of HIV was 9 and 20 times greater among asylum seekers than among non-Western immigrants and Dutch-born women, respectively.

All studies examining SMM among immigrants found a greater risk of SMM among specific subgroups: immigrants from low-income countries compared with Swedish-born women39; immigrants from Sub-Saharan Africa, the Middle East, and the Far East compared with Western women in the Netherlands40; and sub-Saharan Africans compared with nonimmigrants in Canada (specifically, Ontario), Australia, and Denmark.41 Together, these studies suggest that the healthy immigrant effect does not apply to SMM.

By contrast, after removal of deliveries with HIV in our study (shown not to be associated with other comorbidities), the healthy immigrant effect did apply to other immigrants (although not to refugees who showed risks similar to those of nonimmigrants). The differences between previous studies and ours may be attributed to subgroup examination in other studies and Canadian immigration policies, which select for healthier immigrants and, to a lesser extent, refugees.

Limitations and Strengths

Our study had some limitations. First, misclassification of the nonimmigrant group may cause RRs to be biased slightly toward the null when the comparator is nonimmigrants. Second, the SMM indicator includes both incident and prevalent SMM subtypes, making it difficult to describe SMM solely in terms of risk. Third, we did not capture home deliveries, although these were only 1% to 2% of all births in Ontario.42

Findings of risk of SMM subtypes for specific exposure groups should be interpreted with caution, particularly for noninterventions because of the potential underascertainment of these SMM subtypes.32 Because differential underascertainment is unlikely, interpretations of RRs for SMM subtypes may be less problematic. Underascertainment as it relates to the SMM composite indicator is limited in 3 ways. First, severe conditions, such as the SMM subtypes, are less likely to suffer from underreporting43 and are more likely to be accurately reported.32 Second, a mother with severe illness is likely to have comorbidities, and because numerous diagnostic and procedure codes are used to identify SMM, the chances of identifying all mothers with severe illness is increased. Third, the SMM indicator includes procedures known to be more accurately reported than are diagnoses,32 with high positive predictive values and few false positives.43 Therefore, including procedural codes reduced underascertainment through accurate reporting.

Finally, 37% of mothers had 2 or more deliveries included in this data set, suggesting nonindependence of the outcome among deliveries to the same mother that is unaccounted for.44 However a sensitivity analysis indicated that clustering deliveries within a mother did not substantially change the results.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to examine SMM in a large refugee population in a prominent high-income immigrant-receiving country. We accurately captured refugee status on the basis of objective information collected for legal purposes and had sufficient statistical power to address the research questions.

Conclusions

We found that refugee women in Ontario experienced a higher risk of SMM than did immigrants and nonimmigrants, which we attributed to a much higher prevalence of HIV among refugees. Of all the SMM subtypes, the greatest disparity was for HIV. In addition, we found immigration policies to be important determinants of SMM disparities. There was a significant increase in SMM among refugees compared with those who had immigrated recently, suggesting that the IRPA was effective in shifting refugee immigration toward humanitarian protection. Although IRPA formally emphasized humanitarian protection above a refugee’s ability to not place excessive demands on health services, we found that the significant excess of unspecified HIV/AIDS among deliveries to refugee women did not translate into higher demands on the health care system at the time of delivery compared with others with HIV/AIDS. Additional research is needed to examine less severe morbidities among refugee mothers in Canada and other high-income countries particularly because of the higher prevalence of HIV among refugee women.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (award MOP-123267) and the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences (ICES), which is supported by an annual grant from the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care (MOHLTC). S. Wanigaratne was supported by a University of Toronto Open Fellowship. M. L. Urquia holds a Canadian Institutes of Health Research New Investigator award.

Note. The opinions, results, and conclusions reported in this article are those of the authors and are independent from the funding sources. No endorsement by ICES or the MOHLTC is intended or should be inferred.

Human Participant Protection

This study was approved by the research ethics boards of Sunnybrook Hospital, St. Michael’s Hospital, and the University of Toronto, Toronto, Canada.

References

- 1.United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. UNHCR mid-year trends in 2014. 2014 Available at: http://unhcr.org/54aa91d89.html. Accessed April 9, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 2.United Nations Relief and Works Agency. UNRWA in figures as of 1 July 2014. 2014 Available at: http://www.unrwa.org/sites/default/files/in_figures_july_2014_en_06jan2015_1.pdf. Accessed April 9, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 3.United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. Displacement—the new 21st century challenge: UNHCR global trends 2012. 2013 Available at: http://unhcr.org/globaltrendsjune2013/UNHCR%20GLOBAL%20TRENDS%202012_V05.pdf. Accessed May 15, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Citizenship and Immigration Canada. Facts and figures 2013—immigration overview: permanent residents. 2014. Available at: http://www.cic.gc.ca/english/resources/statistics/facts2013/permanent/12.asp. Accessed May 1, 2015.

- 5.Citizenship and Immigration Canada. Canada facts and figures: immigration overview permanent and temporary residents 2011. 2012 Available at: http://www.cic.gc.ca/english/pdf/research-stats/facts2011.pdf. Accessed May 15, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 6.United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. Frequently asked questions about resettlement. Available at: http://www.unhcr.org/4ac0873d6.html. Accessed May 1, 2015.

- 7.Government of Canada. Guide 6000—convention refugees abroad and humanitarian-protected persons abroad. 2015. Available at: http://www.cic.gc.ca/English/information/applications/guides/E16000TOC.asp. Accessed May 1, 2015.

- 8.Government of Canada. Determine your eligibility—refugee status from inside Canada. 2012. Available at: http://www.cic.gc.ca/english/refugees/inside/apply-who.asp. Accessed May 1, 2015.

- 9.Green AG, Green DA. The economic goals of Canada’s immigration policy: past and present. Can Public Policy. 1999;25(4):425–451. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Knowles V. Strangers at Our Gates: Canadian Immigration and Immigration Policy, 1540–2006. Toronto, Ontario: Dundurn Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Government of Canada. Family sponsorship. 2014. Available at: http://www.cic.gc.ca/english/immigrate/sponsor/index.asp. Accessed May 1, 2015.

- 12.Gagnon AJ, Wahoush O, Dougherty G et al. The childbearing health and related service needs of newcomers (CHARSNN) study protocol. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2006;6:31. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-6-31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.World Health Organization. Integrating sexual and reproductive health into health emergency and disaster risk management. 2012. Available at: http://www.who.int/hac/techguidance/preparedness/SRH_HERM_Policy_brief_A4.pdf?ua=. Accessed May 4, 2015.

- 14.United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. Refugee education: a global review. 2011. Available at: http://www.unhcr.org/4fe317589.html. Accessed May 4, 2015.

- 15.DesMeules M, Gold J, Kazanjian A et al. New approaches to immigrant health assessment. Can J Public Health. 2004;95(3):I22–I26. doi: 10.1007/BF03403661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Elo IT, Culhane JF. Variations in health and health behaviors by nativity among pregnant Black women in Philadelphia. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(11):2185–2192. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.174755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Johnson EB, Reed SD, Hitti J, Batra M. Increased risk of adverse pregnancy outcome among Somali immigrants in Washington state. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;193(2):475–482. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2004.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vangen S, Stoltenberg C, Johansen RE, Sundby J, Stray-Pedersen B. Perinatal complications among ethnic Somalis in Norway. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2002;81(4):317–322. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0412.2002.810407.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gagnon AJ, Van Hulst A, Merry L et al. Cesarean section rate differences by migration indicators. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2013;287(4):633–639. doi: 10.1007/s00404-012-2609-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gagnon AJ, Merry L, Haase K. Predictors of emergency cesarean delivery among international migrant women in Canada. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2013;121(3):270–274. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2012.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tunçalp O, Hindin MJ, Souza JP, Chou D, Say L. The prevalence of maternal near miss: a systematic review. BJOG. 2012;119(6):653–661. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2012.03294.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu S, Joseph KS, Bartholomew S et al. Temporal trends and regional variations in severe maternal morbidity in Canada, 2003 to 2007. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2010;32(9):847–855. doi: 10.1016/S1701-2163(16)34656-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zwart JJ, Richters JM, Öry F, de Vries JI, Bloemenkamp KW, van Roosmalen J. Severe maternal morbidity during pregnancy, delivery and puerperium in the Netherlands: a nationwide population-based study of 371,000 pregnancies. BJOG. 2008;115(7):842–850. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2008.01713.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Say L, Souza JP, Pattinson RC WHO Working Group on Maternal Mortality and Morbidity Classifications. Maternal near miss—towards a standard tool for monitoring quality of maternal health care. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2009;23(3):287–296. doi: 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2009.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Klein A. HIV/AIDS and immigration final report. 2001. Available at: http://www.aidslaw.ca/site/wp-content/uploads/2013/04/ImmigRpt-ENG.pdf. Accessed April 29, 2014.

- 26.The Center for HIV Law and Policy. Immigration. Available at: http://www.hivlawandpolicy.org/issues/immigration. Accessed February 9, 2015.

- 27.Government of Canada. Immigration and refugee protection regulations (SOR/2002–227) 2015. Available at: http://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/regulations/SOR-2002-227/section-1.html. Accessed May 1, 2015.

- 28.Calvert C, Ronsmans C. HIV and the risk of direct obstetric complications: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2013;8(10):e74848. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0074848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Joseph KS, Liu S, Rouleau J et al. Severe maternal morbidity in Canada, 2003 to 2007: surveillance using routine hospitalization data and ICD-10CA codes. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2010;32(9):837–846. doi: 10.1016/S1701-2163(16)34655-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision: Canadian Enhancement. Ottawa, Ontario, Canada: Canadian Institute for Health Information; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Canadian Classification of Health Interventions. Ottawa, Ontario, Canada: Canadian Institute for Health Information; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Joseph KS, Fahey J Canadian Perinatal Surveillance System. Validation of perinatal data in the Discharge Abstract Database of the Canadian Institute for Health Information. Chronic Dis Can. 2009;29(3):96–100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.United Nations Statistics Division. Composition of macro geographical (continental) regions, geographical sub-regions, and selected economic and other groups. 2013. Available at: https://unstats.un.org/unsd/methods/m49/m49regin.htm. Accessed April 3, 2014.

- 34.Canadian Institute for Health Information. Canadian coding standards for version 2015 ICD-10-CA and CCI. 2015. Available at: https://secure.cihi.ca/estore/productFamily.htm?locale=en&pf=PFC2785&lang=en&media. Accessed February 9, 2015.

- 35.Hacker NF, Gambone JC, Hobel CJ. Hacker & Moore’s Essentials of Obstetrics and Gynecology. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders Elsevier; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Joint United Nations Programme on HIV and AIDS. Regional fact sheet 2012. Available at: http://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/en/media/unaids/contentassets/documents/epidemiology/2012/gr2012/2012_FS_regional_ssa_en.pdf. Accessed May 6, 2015.

- 37.Public Health Agency of Canada. HIV/AIDS epi updates. Chapter 13: HIV/AIDS in Canada among people from countries where HIV is endemic. 2012. Available at: http://www.catie.ca/sites/default/files/HIV-Aids_EpiUpdates_Chapter13_EN.pdf. Accessed April 5, 2014.

- 38.Van Hanegem N, Miltenburg AS, Zwart JJ, Bloemenkamp KW, Van Roosmalen J. Severe acute maternal morbidity in asylum seekers: a two-year nationwide cohort study in the Netherlands. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2011;90(9):1010–1016. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0412.2011.01140.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wahlberg A, Rööst M, Haglund B, Högberg U, Essén B. Increased risk of severe maternal morbidity (near-miss) among immigrant women in Sweden: a population register-based study. BJOG. 2013;120(13):1605–1611. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.12326. discussion 1612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zwart JJ, Jonkers MD, Richters A et al. Ethnic disparity in severe acute maternal morbidity: a nationwide cohort study in the Netherlands. Eur J Public Health. 2011;21(2):229–234. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckq046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Urquia ML, Glazier RH, Mortensen L et al. Severe maternal morbidity associated with maternal birthplace in three high-immigration settings. Eur J Public Health. 2015;25(4):620–625. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/cku230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.College of Midwives of Ontario. The facts about home birth in Ontario. Available at: http://www.cmo.on.ca/resources/Public/6.%20Factsheet_Facts%20about%20Home%20Birth_RESOURCES_2012.pdf. Accessed April 3, 2014.

- 43.Lain SJ, Hadfield RM, Raynes-Greenow CH et al. Quality of data in perinatal population health databases. Med Care. 2012;50(4):e7–e20. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31821d2b1d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Louis GB, Dukic V, Heagerty PJ et al. Analysis of repeated pregnancy outcomes. Stat Methods Med Res. 2006;15(2):103–126. doi: 10.1191/0962280206sm434oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]