Abstract

Objectives. We set out to assess the occurrence of new depression and anxiety diagnoses in women 3 years after they sought an abortion.

Methods. We conducted semiannual telephone interviews of 956 women who sought abortions from 30 US facilities. Adjusted multivariable discrete-time logistic survival models examined whether the study group (women who obtained abortions just under a facility’s gestational age limit, who were denied abortions and carried to term, who were denied abortions and did not carry to term, and who received first-trimester abortions) predicted depression or anxiety onset during seven 6-month time intervals.

Results. The 3-year cumulative probability of professionally diagnosed depression was 9% to 14%; for anxiety it was 10% to 15%, with no study group differences. Women in the first-trimester group and women denied abortions who did not give birth had greater odds of new self-diagnosed anxiety than did women who obtained abortions just under facility gestational limits.

Conclusions. Among women seeking abortions near facility gestational limits, those who obtained abortions were at no greater mental health risk than were women who carried an unwanted pregnancy to term.

There has been much interest in understanding the effects of abortion, one of the most commonly performed surgical procedures,1,2 on women’s mental health outcomes. Leading reviews on this topic have found no evidence of mental health harm from an abortion,3–6 with the exception of 1 review7 which has been critically refuted.5,8–11 These reviews have called for more research of women seeking abortion beyond the first trimester, longitudinal studies, studies that control for preexisting mental health conditions, and studies that compare women who have had an abortion to women who want an abortion but are unable to get one.3–5

Most of the few longitudinal studies available have been conducted outside of the United States. A Danish population-based cohort study assessed the onset of a first psychiatric event before and up to 12 months after a first-trimester abortion and found no increased risk of mental disorders after abortion.12 A Norwegian study followed 120 women for 5 years and compared the psychological response of women who had first-trimester abortions to women who had miscarriages,13 finding no differences in depression or anxiety between the 2 groups.13 Fergusson et al. published a series of articles based on a longitudinal study conducted in New Zealand that suggested that abortion is associated with an increased risk of mental health problems.14,15 These studies, however, have a number of shortcomings that have been discussed elsewhere and may not be generalizable to the US setting.4 One of the few longitudinal US studies is a secondary analysis of the National Comorbidity Survey that compared the mental health outcomes of women who obtained abortions to women who gave birth.16 In this study, the predictive effect of abortion on mental health conditions disappeared when analyses controlled for mental health history.16

In this article, we report on the first 3 years of a 5-year longitudinal study, the Turnaway Study, which was specifically designed to examine the psychological consequences of undergoing or being denied an abortion in the United States. Previous findings from the Turnaway Study have demonstrated that most women seeking abortions for financial-, timing-, or partner-related reasons17 commonly express feelings of relief after the abortion and feel that abortion was the right decision.18 The mental health symptom trajectories of women who sought an abortion differed little from those who were denied one; however, both improved over time.19 Our previous analysis19 assessed self-reported mental health symptoms at 5 discrete points in time over 2 years (potentially missing symptoms of anxiety and depression that may have occurred in between interview dates or after 2 years), and it did not assess women’s severity of symptoms or other circumstances that may have led to a clinical diagnosis of depression or anxiety. This study further contributes to the literature by assessing diagnoses of new depression and anxiety disorders that may have occurred in women at any point up to 3 years after having sought an abortion.

METHODS

The Turnaway Study is a prospective, longitudinal, telephone–interview study of the impact of receiving versus being denied an abortion on women’s physical, psychological, and socioeconomic well-being. Women were recruited at abortion facilities with the latest gestational limit for providing abortion of any facility within 150 miles. Facilities were identified using the National Abortion Federation (NAF) directory and contacts within the abortion research community and thus included facilities that were and were not NAF members. Gestational age limits for participating facilities ranged from 10 weeks through the end of the second trimester. Study details have been published previously.20,21

Study groups were recruited at a ratio of 2:1:1 and included (1) the near-limit abortion group—women who presented for abortion up to 2 weeks under a facility’s gestational limit and who received abortions; (2) the turnaway group—women who presented for abortion up to 3 weeks over a facility’s gestational limit and who were denied abortions; and (3) the first-trimester abortion group—women in their first trimester who received abortions. Because approximately 90% of abortions occur in the first trimester,22 the first-trimester group was included to assess the extent to which women in the near-limit group differed from the typical experience of abortion in the United States. Baseline telephone interviews were scheduled 8 days after women sought the abortion; women were then interviewed by telephone every 6 months for 5 years. Women received a $50 gift card by mail after each interview as compensation for their time.

Study Participants

Study participants included English- and Spanish-speaking women aged 15 years or older with no known fetal anomalies or demise. Women presented for abortion care between January 2008 and December 2010 at 30 facilities throughout the United States within the gestational age specifications of 1 of 3 designated study groups. Women who sought an abortion because of a fetal anomaly were excluded because the psychological response to such an event is likely different from the experiences of women who sought an abortion as a result of an unwanted pregnancy.23

Measures

The structured interview guide included questions for participants about their sociodemographic characteristics, experiences becoming pregnant, pregnancy planning, and the abortion decision-making process. Sociodemographic characteristics included baseline age, race/ethnicity (White, Black, Hispanic/Latina, and other), education (more than high school vs high school graduation or less than high school), employment status (part or full time vs not employed), health insurance coverage, and marital status (single, married, and divorced or widowed). Gestational age was included as a continuous variable measured in weeks at time of recruitment; this variable was excluded as a covariate in the multivariable models because, by design, it was associated with the study group. History of abuse and substance use included 3 dichotomous baseline variables: history of child abuse or neglect, ever used illicit drugs prior to pregnancy recognition, and ever experienced problem alcohol use prior to pregnancy discovery.

New depression and anxiety diagnoses were included as our main outcome measures and were collected every 6 months throughout the study period. Approximately 1 week after seeking an abortion, participants were asked whether a doctor or health professional had ever told them that they had a depressive disorder such as major depression, depression, dysthymia, or bipolar disorder. Separately they were asked whether a doctor or health professional had ever told them that they had an anxiety disorder, including panic, obsessive-compulsive, anxiety, and posttraumatic stress. If participants answered “yes” to these questions they were considered to have been diagnosed with depression or anxiety by a health professional. Participants who reported a diagnosed depressive or anxiety disorder were asked whether they were currently receiving any treatment, such as therapy or medication, for this condition. To capture potential cases of depression or anxiety among women who may not have had access to a medical professional, women were also asked whether they felt like they had suffered from any conditions, regardless of whether a health professional had diagnosed one. Participants were asked to name the condition. If participants reported a depressive or anxiety-related condition, we considered these diagnoses to be self-diagnoses of depression and anxiety. Women who reported a professional diagnosis for a condition were not coded as having a self-diagnosis for that same condition. At each follow-up interview, participants were asked whether they had received any new diagnoses for depression or anxiety in the past 6 months. Our outcome of interest was the interview wave when the first onset of a diagnosis was reported. The 4 outcome variables included (1) new professional depression diagnoses, (2) new professional anxiety diagnoses, (3) new self-diagnoses of depression, and (4) new self-diagnoses of anxiety.

Time to Diagnosis

Time measurements corresponded to the 7 waves of interviews that occurred every 6 months, with the first wave used only to assess baseline measures, including history of depression or anxiety diagnoses. At each follow-up interview, participants were asked whether they had experienced a mental health event in the previous 6 months. Measurements of time to diagnosis included whether the participant reported a new diagnosis during any of the six 6-month intervals (0–6, 6–12, 12–18, 18–24, 24–30, and 30–36 months) after having sought an abortion.

Statistical Analysis

We estimated Kaplan–Meier curves to describe the distribution of times to onset of depression or anxiety during each 6-month interval. Life table analyses were used to estimate the unadjusted cumulative probability of developing a new depressive or anxiety condition. The log-rank test compared study group differences in times to diagnoses. We fit 4 multivariable discrete-time logistic survival models to examine the relationship between the study group and onset of new self- or professional diagnoses of a depressive or anxiety disorder during the 3-year period, adjusting for baseline covariates as necessary. In this discrete-time approach, we used 6-month intervals rather than assuming continuous time because we assessed whether diagnoses occurred at any time within each time interval. Baseline variables known to be associated with depression and anxiety were added as model covariates and included age, race/ethnicity, education, employment, parity, marital status, insurance coverage, child abuse or neglect, history of drug use, and problem alcohol use. History of a professional anxiety diagnosis was used as a covariate in the models with onset of depression as an outcome. History of a professional depressive diagnosis was used as a covariate in models that looked at the onset of anxiety diagnoses. Participants who had already experienced the model outcome at baseline were excluded from each respective multivariable discrete-time logistic analysis.

We conducted 2 separate sensitivity analyses to test the robustness of our results. The first set of sensitivity analyses limited all analyses to the 414 women from the 7 sites with a recruitment participation rate of 50% or greater. The second set of sensitivity analyses excluded the 15 women who placed their babies for adoption. All analyses accounted for clustering by recruitment site using the robust option. Analyses were conducted using Stata version 13.1 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX).

RESULTS

Nearly 2 in 5 (37.5%) eligible participants approached consented to participate, of which 85% (n = 956) completed the baseline interview. One facility was excluded from analyses because 95% of women in the turnaway group obtained an abortion elsewhere after being denied abortion care, providing an insufficient sample of turnaway women from this site. Two women in the near-limit group and 1 woman in the first-trimester group were excluded because they later reported that they had decided not to have an abortion. This left a final sample of 877 participants: 413 women in the near-limit group, 210 women in the turnaway group, and 254 women in the first-trimester group. For analyses, turnaway women were separated into those who gave birth, including 15 women who subsequently placed their baby for adoption (turnaway–birth group, n = 160) and those who had an abortion or miscarriage (turnaway–no-birth group, n = 50).

Of the participants who completed a baseline interview, 92% were retained at the 6-month follow-up and 93% to 95% at each subsequent interview. Baseline history of depression, anxiety, suicidal ideation, and study group were not significantly associated with loss to follow-up.

Table 1 describes the characteristics of participants by study group. At baseline, 19% of women in the near-limit group reported ever being professionally diagnosed with a depressive disorder, compared with 16% of turnaway–birth, 26% of turnaway–no-birth, and 25% of first-trimester women (P = .135; Table 1). History of professional anxiety diagnoses was 15% for near-limit women, 12% for turnaway–birth women, 18% for turnaway–no-birth women, and 16% for first-trimester women, with no statistically significant differences among groups (P = .795).

TABLE 1—

Characteristics of Participants (n = 877) by Study Group: United States, 2008–2013

| Demographics | Near-Limit (n = 413), No. (%) or Mean ±SD | Turnaway–Birth (n = 160), No. (%) or Mean ±SD | Turnaway–No-Birth (n = 50), No. (%) or Mean ±SD | First-Trimester (n = 254), No. (%) or Mean ±SD | Pa |

| Age, y | 24.9 ±5.9 | 23.4 ±5.5 | 24.4 ±6.2 | 25.9 ±5.7 | < .001 |

| Race/ethnicity | .052 | ||||

| White | 132 (32) | 40 (25) | 21 (42) | 99 (39) | |

| Black | 131 (32) | 54 (34) | 14 (28) | 80 (32) | |

| Hispanic/Latina | 87 (21) | 45 (28) | 7 (14) | 54 (21) | |

| Other | 63 (15) | 21 (13) | 8 (16) | 21 (8) | |

| Highest level of education | .275 | ||||

| < high school | 76 (18) | 39 (24) | 10 (20) | 41 (16) | |

| High school or GED | 142 (34) | 55 (34) | 13 (26) | 78 (31) | |

| Associate (some college or technical school) | 167 (40) | 57 (36) | 23 (46) | 107 (42) | |

| College | 28 (7) | 9 (6) | 4 (8) | 28 (11) | |

| Employed | 224 (54) | 64 (40) | 24 (48) | 161 (63) | < .001 |

| Marital status | .352 | ||||

| Single | 329 (80) | 134 (84) | 39 (78) | 194 (76) | |

| Married | 33 (8) | 16 (10) | 3 (6) | 28 (11) | |

| Divorced or widowed | 51 (12) | 10 (6) | 8 (16) | 32 (13) | |

| Has health insurance coverage | 283 (69) | 119 (74) | 32 (65) | 178 (70) | .778 |

| Pregnancy-related characteristics | |||||

| Gestational age, wk | 19.9 ±4.1 | 23.4 ±3.4 | 19.2 ±4.0 | 7.8 ±2.4 | < .001 |

| Parity | .166 | ||||

| Nulliparous | 140 (34) | 75 (47) | 20 (40) | 97 (38) | |

| Have baby < 1 y and may or may not have additional births | 51 (12) | 10 (6) | 4 (8) | 28 (11) | |

| > 1 previous births; no baby < 1 y | 110 (27) | 33 (21) | 14 (28) | 54 (21) | |

| > 2 previous births; no baby < 1 y | 112 (27) | 42 (26) | 12 (24) | 75 (30) | |

| History of abuse and substance use | |||||

| Child abuse or neglect | 108 (26) | 41 (26) | 7 (14) | 70 (28) | .199 |

| Any illicit drug use before discovering pregnancy | 52 (13) | 22 (14) | 4 (8) | 45 (18) | .177 |

| Problem alcohol use before discovering pregnancy | 18 (4) | 11 (7) | 5 (10) | 18 (7) | .258 |

| Mental health history | |||||

| Ever been diagnosed by a health professional or received treatment | |||||

| Depressive disorder: diagnosed | 77 (19) | 25 (16) | 13 (26) | 63 (25) | .135 |

| Depressive disorder: currently receiving treatment | 23 (6) | 6 (4) | 2 (4) | 21 (8) | .237 |

| Anxiety disorder: diagnosed | 62 (15) | 19 (12) | 9 (18) | 41 (16) | .795 |

| Anxiety disorder: currently receiving treatment | 27 (7) | 6 (4) | 4 (8) | 14 (6) | .761 |

| Ever felt like you had a mental condition whether or not a health professional told you | |||||

| Depressive disorder | 33 (8) | 10 (6) | 9 (18) | 18 (7) | .087 |

| Anxiety disorder | 19 (5) | 7 (4) | 2 (4) | 21 (8) | .19 |

Note. GED = general equivalency diploma.

P values were based on multiple comparisons using a postestimation command.

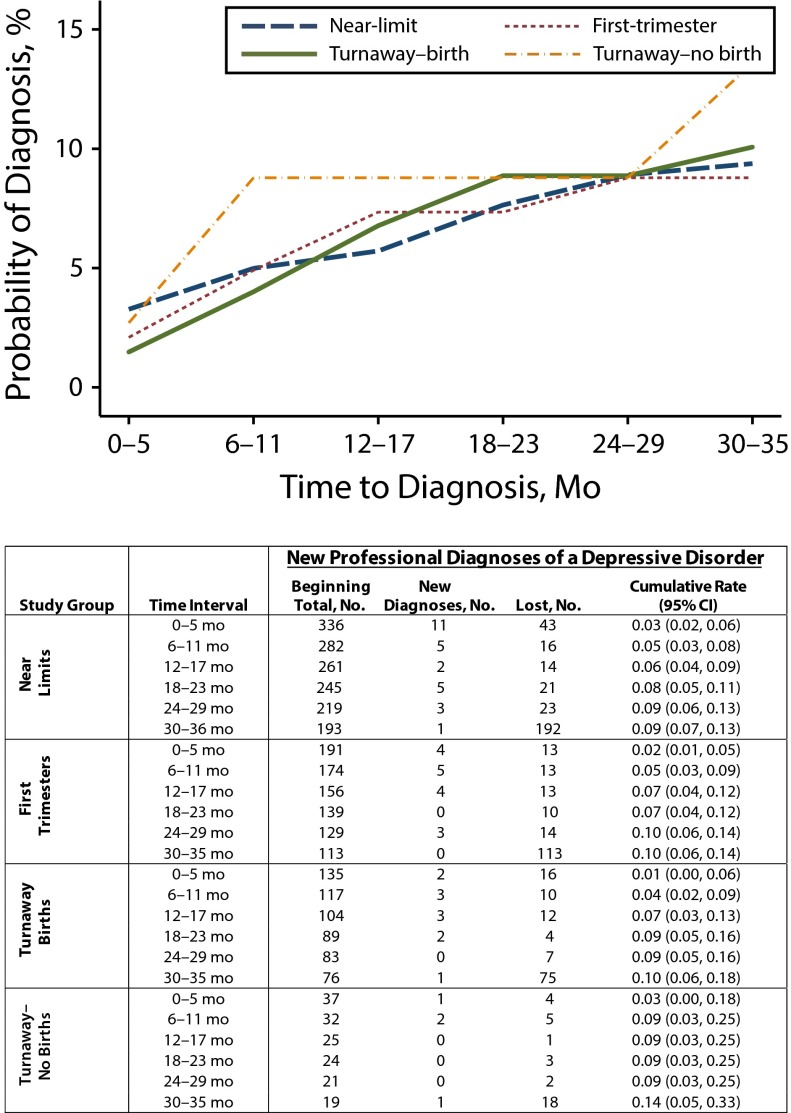

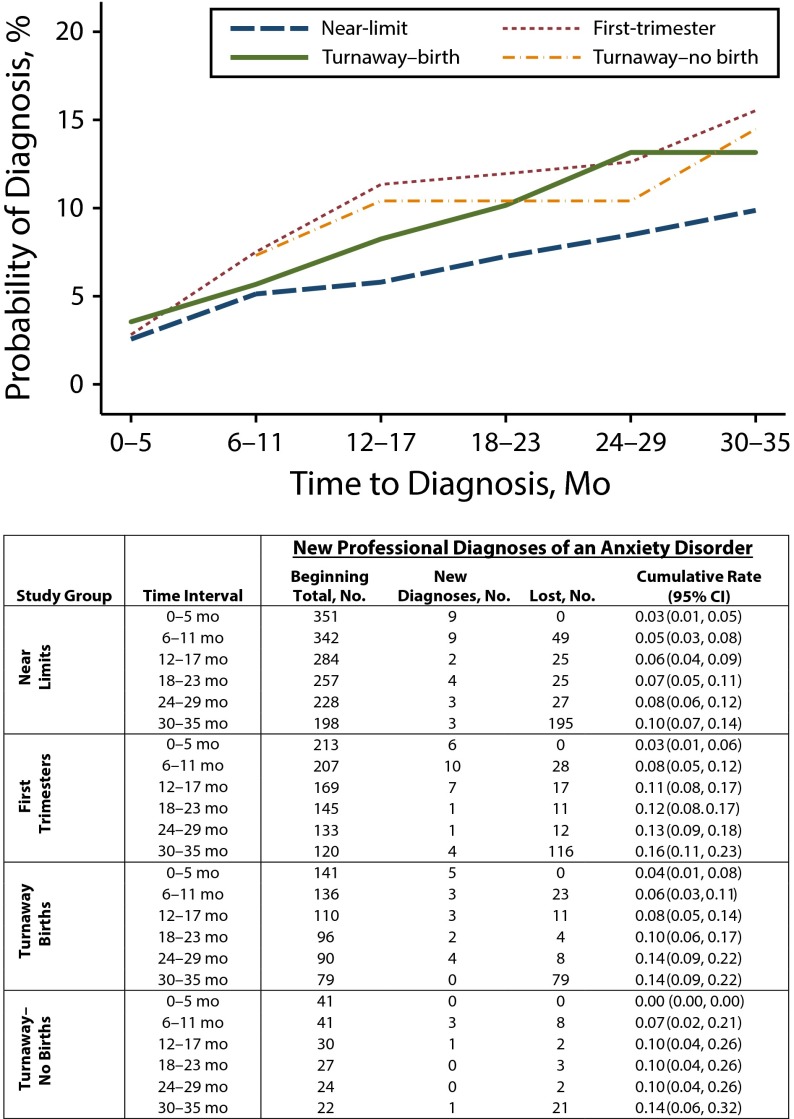

After excluding participants who experienced the model outcome at baseline from each respective multivariable discrete-time logistic analysis, we were left with a final sample of 699 for the professional depression diagnoses model, 807 for the self-diagnoses of depression model, 746 for professional anxiety diagnoses, and 828 for the self-diagnoses of anxiety model. Three years after having sought an abortion, the cumulative probability of women who experienced a new, professionally diagnosed depressive condition was 9% to 14%, with no variation by study group (log-rank test, P = .91; Figure 1). The cumulative probability of onset of a professionally diagnosed anxiety condition during this same 3-year timeframe was 10% to 16%, with no study group differences (log-rank test, P = .3; Figure 2).

FIGURE 1—

Kaplan–Meier curves and life table estimating the time to receiving a new depression diagnosis after seeking an abortion, by study group: United States, 2008–2013.

Note. CI = confidence interval.

FIGURE 2—

Kaplan–Meier curves and life table estimating the time to receiving a new anxiety diagnosis after seeking an abortion, by study group: United States, 2008–2013.

Note. CI = confidence interval.

The results of 4 adjusted discrete-time logistic models for the onset of mental health conditions are presented in Table 2. There were no statistically significant study group differences in new cases of professionally diagnosed depression or anxiety. There were also no significant study group differences in self-diagnosed depression. However, women in the first-trimester and turnaway–no-birth groups were at greater odds of new self-reported anxiety (AOR = 1.52; CI = 1.02, 2.26) than the near-limit group (AOR = 2.71; CI = 1.80, 4.08). Across groups, the odds of reporting a new self-diagnosis of a depressive disorder in the first 2 years after having sought an abortion were higher than during the 30- to 36-month study interval.

TABLE 2—

Multivariable Discrete-Time Survival Models of the Association Between Study Group and New Professional or Self-Reported Depressive or Anxiety Disorder Diagnoses: United States, 2008–2013

| New Professional Diagnoses |

New Self-Diagnoses |

|||||||

| Study Group | AOR | P | RSE | 95% CI | AOR | P | RSE | 95% CI |

| Depressive disorder diagnoses | ||||||||

| Near-limit (Ref) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||

| First-trimester | 0.90 | .708 | 0.25 | 0.52, 1.57 | 1.31 | .129 | 0.23 | 0.92, 1.85 |

| Turnaway–birth | 1.26 | .453 | 0.39 | 0.69, 2.31 | 1.33 | .229 | 0.32 | 0.83, 2.13 |

| Turnaway–no-birth | 1.94 | .381 | 1.48 | 0.44, 8.61 | 1.04 | .941 | 0.53 | 0.38, 2.80 |

| Time to diagnosis, mo | ||||||||

| 0–6 | 2.94 | .047 | 1.59 | 1.01, 8.51 | 3.78 | < .001 | 1.36 | 1.86, 7.66 |

| 6–12 | 3.01 | .031 | 1.54 | 1.11, 8.21 | 3.54 | .001 | 1.39 | 1.64, 7.65 |

| 12–18 | 2.01 | .292 | 1.32 | 0.55, 7.32 | 2.34 | .038 | 0.96 | 1.05, 5.23 |

| 18–24 | 1.81 | .311 | 1.06 | 0.57, 5.71 | 2.66 | .023 | 1.15 | 1.14, 6.21 |

| 24–30 | 1.43 | .615 | 1.01 | 0.36, 5.70 | 1.55 | .376 | 0.77 | 0.59, 4.12 |

| 30–36 (Ref) | 1.00 | |||||||

| Anxiety disorder diagnoses | ||||||||

| Near-limit (Ref) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||

| First-trimester | 1.42 | .152 | 0.35 | 0.88, 2.29 | 1.52 | .039 | 0.31 | 1.02, 2.26 |

| Turnaway–birth | 1.33 | .353 | 0.41 | 0.73, 2.45 | 1.44 | .138 | 0.36 | 0.89, 2.35 |

| Turnaway–no-birth | 1.39 | .512 | 0.70 | 0.52, 3.73 | 2.71 | < .001 | 0.57 | 1.80, 4.08 |

| Time to diagnosis, mo | ||||||||

| 0–6 | 1.30 | .541 | 0.55 | 0.56, 2.99 | 1.97 | .06 | 0.71 | 0.97, 4.01 |

| 6–12 | 1.73 | .05 | 0.48 | 1.00, 2.98 | 1.85 | .118 | 0.72 | 0.86, 3.98 |

| 12–18 | 1.12 | .815 | 0.55 | 0.43, 2.95 | 1.82 | .105 | 0.68 | 0.88, 3.77 |

| 18–24 | 0.69 | .407 | 0.31 | 0.29, 1.65 | 1.17 | .681 | 0.44 | 0.56, 2.46 |

| 24–30 | 0.77 | .608 | 0.40 | 0.28, 2.13 | 1.06 | .888 | 0.47 | 0.45, 2.52 |

| 30–36 (Ref) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||

Note. AOR = adjusted odds ratio; CI = confidence interval; RSE = robust standard error. Models were adjusted for the effects of race, age, parity, education, marital and employment status, health insurance coverage, drug and problem alcohol use prior to pregnancy recognition, history of depression or anxiety diagnosis, and history of child abuse and neglect.

Findings from sensitivity analyses limited to the women from sites with high recruitment rates were mostly consistent with our main findings, with the exception that the turnaway–no-birth group was significantly more likely than near-limit women to report new professional diagnoses of depression (AOR = 7.59; CI = 1.51, 38.20) and the first-trimester group was significantly more likely than the near-limit group to report new self-diagnoses of depression (AOR = 1.66; CI = 1.87, 2.32). Results of our second set of sensitivity analyses that excluded women who had placed their babies for adoption were consistent with our main findings, except that the turnaway–birth group was now significantly more likely to experience a new self-diagnosis of anxiety than the near-limit group (AOR = 1.68; CI = 1.05, 2.68).

DISCUSSION

The Turnaway Study was the first study in the United States to assess whether terminating an unwanted pregnancy resulted in adverse mental health outcomes over time by comparing women who obtained an abortion to women who had sought an abortion but were turned away. It has been difficult in the past for researchers to isolate any psychological responses after an abortion from other factors, such as the experience of having an unwanted pregnancy.24 Most other studies have compared women who obtained an abortion to women who did not want one or to women with wanted pregnancies, such as women who experienced miscarriages or wanted childbirth.5 By following women who were seeking a wanted abortion for 3 years, controlling for mental health history and other factors known to be related with depression and anxiety, and comparing the psychological response of women having abortion to those denied a wanted abortion, we were able to isolate the effects of abortion on women’s subsequent mental health. Furthermore, by including a substantial number of women who sought a later abortion and comparing them to women who sought one in their first trimester, we gained a better understanding of the psychological responses of this understudied group. Consistent with several reviews,3–5 we found that women who obtained a later abortion were not at increased risk for experiencing a new diagnosed depression or anxiety condition than women who carried an unwanted pregnancy to term or women who obtained a first-trimester abortion.

Those in the first-trimester abortion group were at slightly elevated risk for self-reporting an anxiety disorder than women who obtained an abortion in the near-limit abortion group. The reasons why women in the first-trimester group were more likely to experience or report anxiety than women in the near-limit group is not known.

Women who were initially denied an abortion but went on to have an abortion or miscarriage (turnaway–no-birth group) were most likely to develop a self-diagnosed anxiety condition. This group of women is unique in that they continued to seek pregnancy termination even after being turned away from an abortion, primarily because they were earlier in pregnancy and had more options.25 Previous analyses from the Turnaway Study have demonstrated that the primary reasons for being unable to obtain an abortion after having been denied one included procedure and travel costs and difficulty finding and getting to an appropriate provider.25 Thus, those who were able to obtain an abortion after having been denied one likely had to overcome several barriers related to cost, travel, and identifying a provider, which may have contributed to the heightened feelings of anxiety among this group.

Our findings demonstrated that the onset of professionally diagnosed depression or anxiety does not differ by study group. However, both women who received an abortion and women who gave birth were more likely to report self-diagnoses of depression in the first year after having sought an abortion than at the end of the study period. This finding suggests something other than having an abortion, potentially the experience of having an unintended pregnancy or the circumstances that lead women to want to terminate the pregnancy, place women at risk for feeling depressed for some time after seeking an abortion. Such circumstances may be intricately linked to the reasons why women seek abortions in the first place, including financial- and partner-related reasons17 or the recent experience of a disruptive life event, which has been found to be common among women who obtain abortions.26

Our previous analyses of this group of women’s depressive and anxiety symptoms were limited in that women reported their symptoms for a 1-week period, every 6 months. By contrast, this study explored the experience of more severe psychological distress that may result in professional diagnoses of depression and anxiety and allowed us to capture any diagnoses that may have occurred at any point in the 3-year study period. By allowing women to report whether they believed themselves to have a psychological disorder, we aimed to capture signs of clinical distress among women who may not have had access to care to obtain a medical diagnosis.

Despite improving upon several of the methodological weaknesses found in prior studies, this study has some important limitations. For survey research standards, our participation rate of less than 40% is low. However, if we consider that women were asked to a participate in 11 lengthy telephone interviews, over a period of 5 years, concerning the stigmatized topic of abortion, and were not offered any direct medical benefit for participating, our participation rate was reasonable and similar to other prospective longitudinal studies.3,24 Another potential concern is that there may have been differential participation by study group. Participation rates for the first-trimester group were somewhat lower than our 2 main comparison groups, the turnaway and near-limit women, who had similar rates of participation (41% and 42%, respectively).25 Onset of depression and anxiety diagnoses may have differed from those who participated and those who did not. Furthermore, we cannot rule out that women suffering from mental health conditions may have been lost to follow-up, potentially biasing our results. However, mitigating some of these concerns is the fact that we controlled for pre-existing depression and anxiety, that baseline mental health history was similar between groups, and that baseline mental health history, including suicidal ideation, were not significantly associated with attrition. Losing less than 6% from wave to wave, our participant retention rate was high, strengthening the validity of our findings. Although our study oversampled women who sought an abortion later in pregnancy, our sample demographics were similar to nationally representative samples of women who sought an abortion, suggesting that these results were generalizable to women who sought an abortion across the country.17,26 Self-reported measures may not accurately reflect whether participants met the clinical criteria for a psychological disorder and should be interpreted with that in mind. In particular, women’s assessment of whether they perceived themselves to have a mental health condition likely varied depending on their interpretation of the condition. Nonetheless, we believe that this measure added to our understanding about women who may not have access to mental health services and thus would have been unable to obtain a professional mental health diagnosis.

Although this study found that self-diagnosed depression was more common closer to the time of seeking abortion than after 3 years, this experience did not differ by study group. Among women seeking an abortion near facility gestational age limits, those who obtained one were at no greater risk of depression or anxiety than women who carried an unwanted pregnancy to term. Our results were consistent with the conclusions of several reviews that have found that abortion is not associated with adverse mental health outcomes.3–6 This finding calls into question the appropriateness of policies that mandate counseling of all women who obtain an abortion on the psychological effects that can accompany them.27 Although some women may benefit from appropriately tailored education and counseling approaches,20 the assumption that all women experience a negative psychological response after an abortion is not supported by this study. The more frequent occurrence of new mental health diagnoses immediately after abortion and being denied an abortion does suggest that other factors in women’s lives, not the experience of the abortion procedure or its aftermath, are associated with more adverse mental health outcomes. These factors may stem from the experience of having an unwanted pregnancy or may reflect the reasons that the pregnancy is unwanted, such as not being ready to parent, a poor relationship with the partner involved, or financial-related reasons.17

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by research and institutional grants from the Wallace Alexander Gerbode Foundation, the David and Lucile Packard Foundation, and an anonymous foundation. The authors thank Rana Barar, Heather Gould, and Sandy Stonesifer for study coordination and management; Mattie Boehler-Tatman, Janine Carpenter, Undine Darney, Ivette Gomez, C. Emily Hendrick, Selena Phipps, Brenly Rowland, Claire Schreiber, and Danielle Sinkford for conducting interviews; Michaela Ferrari, Debbie Nguyen, and Elisette Weiss for project support; Jay Fraser for statistical and database assistance; and all the participating providers for their assistance with recruitment.

Human Participant Protection

Study protocol and procedures for the Turnaway Study received institutional review board approval from the Committee on Human Research at the University of California, San Francisco.

References

- 1.Finer LB, Zolna MR. Unintended pregnancy in the United States: incidence and disparities, 2006. Contraception. 2011;84(5):478–485. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2011.07.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jones RK, Zolna MR, Henshaw SK, Finer LB. Abortion in the United States: incidence and access to services, 2005. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2008;40(1):6–16. doi: 10.1363/4000608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Major B, Appelbaum M, Beckman L, Dutton MA, Russo NF, West C. Abortion and mental health: evaluating the evidence. Am Psychol. 2009;64(9):863–890. doi: 10.1037/a0017497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Charles VE, Polis CB, Sridhara SK, Blum RW. Abortion and long-term mental health outcomes: a systematic review of the evidence. Contraception. 2008;78(6):436–450. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2008.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health at the Royal College of Psychiatrists. Induced Abortion and Mental Health: A Systematic Review of the Mental Health Outcomes of Induced Abortion, Including Their Prevalence and Associated Factors. London, UK: Royal College of Psychiatrists; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Robinson GE, Stotland NL, Russo NF, Lang JA, Occhiogrosso M. Is there an “abortion trauma syndrome”? Critiquing the evidence. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 2009;17(4):268–290. doi: 10.1080/10673220903149119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Coleman PK. Abortion and mental health: quantitative synthesis and analysis of research published 1995–2009. Br J Psychiatry. 2011;199(3):180–186. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.110.077230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Abel KM, Susser ES, Brocklehurst P, Webb RT. Abortion and mental health: guidelines for proper scientific conduct ignored. Br J Psychiatry. 2012;200(1):74–75. doi: 10.1192/bjp.200.1.74a. discussion 78–79, author reply 79–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Polis CB, Charles VE, Blum RW, Gates WH., Sr Abortion and mental health: guidelines for proper scientific conduct ignored. Br J Psychiatry. 2012;200(1):76–77. doi: 10.1192/bjp.200.1.76. discussion 78–79, author reply 79–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kendall T, Bird V, Cantwell R, Taylor C. To meta-analyse or not to meta-analyse: abortion, birth and mental health. Br J Psychiatry. 2012;200(1):12–14. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.111.106112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Steinberg JR, Trussell J, Hall KS, Guthrie K. Fatal flaws in a recent meta-analysis on abortion and mental health. Contraception. 2012;86(5):430–437. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2012.03.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Munk-Olsen T, Laursen TM, Pedersen CB, Lidegaard O, Mortensen PB. Induced first-trimester abortion and risk of mental disorder. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(4):332–339. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0905882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Broen AN, Moum T, Bodtker AS, Ekeberg O. The course of mental health after miscarriage and induced abortion: a longitudinal, five-year follow-up study. BMC Med. 2005;3(18) doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-3-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ, Ridder EM. Abortion in young women and subsequent mental health. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2006;47(1):16–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2005.01538.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ, Boden JM. Abortion and mental health disorders: evidence from a 30-year longitudinal study. Br J Psychiatry. 2008;193(6):444–451. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.108.056499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Steinberg JR, McCulloch CE, Adler NE. Abortion and mental health: findings from The National Comorbidity Survey-Replication. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123(2 pt 1):263–270. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000000092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Biggs MA, Gould H, Foster DG. Understanding why women seek abortions in the US. BMC Womens Health. 2013;13(29) doi: 10.1186/1472-6874-13-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rocca CH, Kimport K, Gould H, Foster DG. Women’s emotions one week after receiving or being denied an abortion in the United States. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2013;45(3):122–131. doi: 10.1363/4512213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Foster DG, Steinberg JR, Roberts SC, Neuhaus J, Biggs MA. A comparison of depression and anxiety symptom trajectories between women who had an abortion and women denied one. Psychol Med. 2015 doi: 10.1017/S0033291714003213. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gould H, Perrucci A, Barar R, Sinkford D, Foster DG. Patient education and emotional support practices in abortion care facilities in the United States. Women’s Health Issues. 2012;22(4):e359–e364. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2012.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dobkin LM, Gould H, Barar R, Ferrari M, Weiss E, Foster DG. Implementing a prospective study of women seeking abortion in the United States: understanding and overcoming barriers to recruitment. Women’s Health Issues. 2014;24(1):e115–e123. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2013.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pazol K, Creanga AA, Burley KD, Hayes B, Jamieson DJ. Abortion surveillance— United States, 2010. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2013;62(8):1–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Foster DG, Gould H, Kimport K. How women anticipate coping after an abortion. Contraception. 2012;86(1):84–90. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2011.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Adler NE, David HP, Major B, Roth SH, Russo NF, Wyatt GE. Psychological factors in abortion: a review. Am Psychol. 1992;47(10):1194–1204. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.47.10.1194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Upadhyay UD, Weitz TA, Jones RK, Barar RE, Foster DG. Denial of abortion because of provider gestational age limits in the United States. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(9):1687–1694. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jones RK, Frohwirth L, Moore AM. More than poverty: disruptive events among women having abortions in the USA. J Fam Plann Reprod Health Care. 2013;39(1):36–43. doi: 10.1136/jfprhc-2012-100311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Guttmacher Institute. State policies in brief: counseling and waiting periods for abortion. Available at: http://www.guttmacher.org/statecenter/spibs/spib_MWPA.pdf. Accessed June 11, 2015.