Abstract

Solitary pulmonary nodules are a common finding on chest radiography and CT. We present the case of an asymptomatic 59-year-old male found to have a 13 mm left upper lobe nodule on CT scan. The patient was asymptomatic and the CT was performed to follow up mediastinal and hilar lymphadenopathy that had been stable on several previous CT scans. He had a history of emphysema and reported a 15 pack-year smoking history. PET-CT was performed which demonstrated mild 18-FDG uptake within the nodule. Given his age and smoking history, malignancy was a consideration and he underwent a wedge resection. Pathological examination revealed a necrobiotic granulomatous nodule with a central thrombosed artery containing a parasitic worm with internal longitudinal ridges and abundant somatic muscle, consistent with pulmonary dirofilariasis. Dirofilaria immitis, commonly known as the canine heartworm, rarely affects humans. On occasion it can be transmitted to a human host by a mosquito bite. There are two major clinical syndromes in humans: pulmonary dirofilariasis and subcutaneous dirofilariasis. In the pulmonary form, the injected larvae die before becoming fully mature and become lodged in the pulmonary arteries.

Keywords: Pulmonary dirofilariasis, zoonoses, canine heartworm, solitary pulmonary nodule, Dirofilaria, D. immitis, zoonotic

CASE REPORT

A 59-year-old male with a past medical history of emphysema, hypertension, and dyslipidemia underwent contrast enhanced computed tomography (CT) of the chest to follow up on borderline enlarged mediastinal and left hilar lymph nodes that had been identified on previous CT (Figures 1–3). He was asymptomatic at the time of the follow up scan and denied respiratory or constitutional symptoms. He was afebrile and his lungs were clear to auscultation. The scan showed a 13 mm nodule in the periphery of the left upper lobe, which was new from a CT approximately 6 months prior. Given a reported smoking history, malignancy was a primary concern and positron emission tomography (PET) CT was performed (Figures 4–6). The lesion demonstrated mild18-Fluorodeoxyglucose (18-FDG) hypermetabolism on PET. There were no additional suspicious lesions.

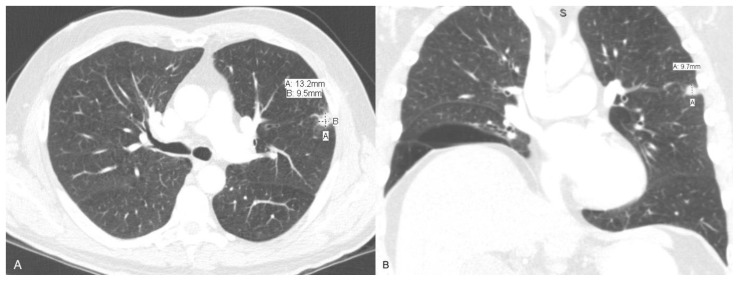

Figure 1.

57 year old male with pulmonary dirofilariasis.

Findings: CT demonstrates an irregular nodule within the peripheral left upper lobe measuring 13 × 10 × 10 mm.

Technique: Axial(A) and coronal (B) CT, 399 mAs, 120 kVp, 2.5 mm slice thickness, 60 ml Optiray 350.

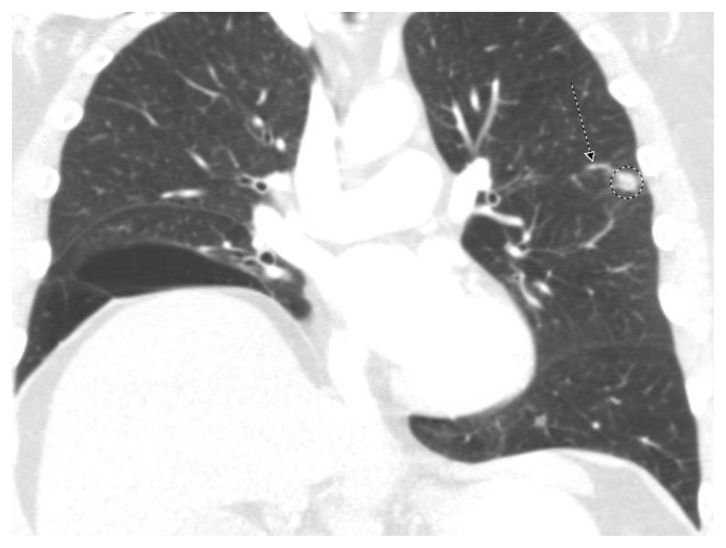

Figure 2.

57 year old male with pulmonary dirofilariasis.

Findings: CT demonstrates an irregular nodule within the peripheral left upper lobe (dashed circle) with adjacent feeding artery (dashed arrow).

Technique: Coronal CT, 399 mAs, 120 kVp, 2.5 mm slice thickness, 60 ml Optiray 350.

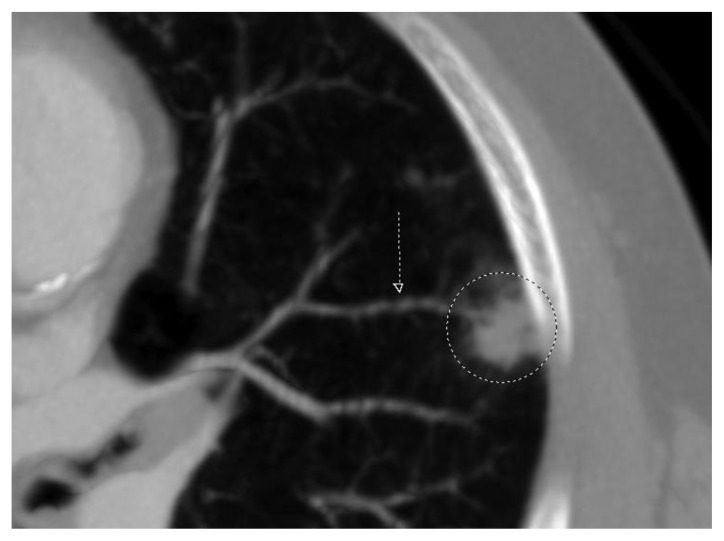

Figure 3.

57 year old male with pulmonary dirofilariasis.

Findings: CT demonstrates an irregular nodule within the peripheral left upper lobe (dashed circle) with feeding artery (dashed arrow).

Technique: Curved reformat axial CT, 399 mAs, 120 kVp, 2.5 mm slick thickness,60 ml Optiray 350.

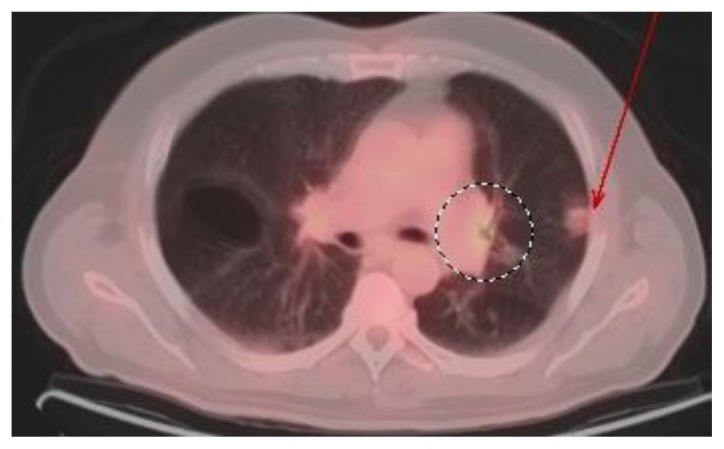

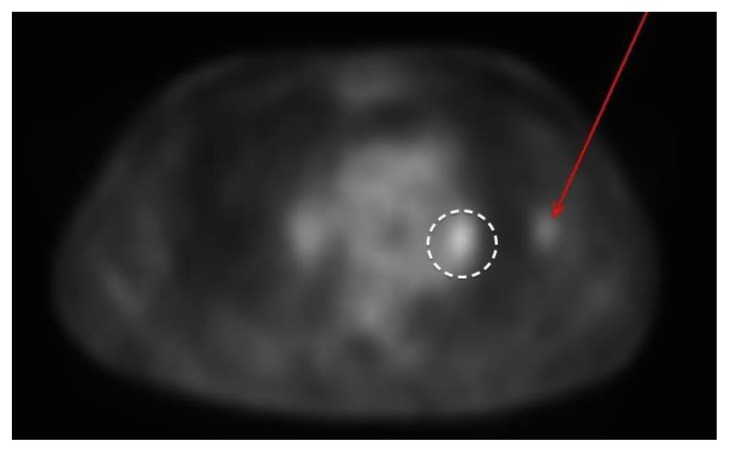

Figure 4.

57 year old male with pulmonary dirofilariasis.

Findings: Fused PET-CT demonstrates mild 18-FDG uptake in a left upper lobe nodule (red arrow) and left hilar lymph nodes (dashed circle). Maximum SUV of the nodule was 2.2. Maximum SUV of the left hilar lymph nodes was 2.6. Average liver SUV was 2.5.

Technique: Fused axial PET-CT, 399 mAs, 120 kVp, 2.5 mm slick thickness, 60 ml Optiray 350, 14.4 mCi 18-FDG, images obtained at approximately 60 minutes

Figure 5.

57 year old male with pulmonary dirofilariasis.

Findings: Fused PET-CT demonstrates mild 18-FDG uptake in a left upper lobe nodule (red arrow) and left hilar lymph nodes (dashed circle). Maximum SUV of the nodule was 2.2. Maximum SUV of the left hilar lymph nodes was 2.6. Average liver SUV was 2.5.

Technique: Fused coronal PET-CT, 399 mAs, 120 kVp, 2.5 mm slick thickness, 60 ml Optiray 350, 14.4 mCi 18-FDG, images obtained at approximately 60 minutes

Figure 6.

57 year old male with pulmonary dirofilariasis.

Findings: PET demonstrates mild 18-FDG uptake in a left upper lobe nodule (red arrow) and left hilar lymph nodes (dashed circle). Maximum SUV of the nodule was 2.2. Maximum SUV of the left hilar lymph nodes was 2.6. Average liver SUV was 2.5.

Technique: Attenuation correction axial PET, 14.4 mCi 18-FDG, images obtained at approximately 60 minutes

Imaging Findings

The patient’s CT scan demonstrated an irregularly shaped non-calcified solid nodule in the periphery of the left upper lobe, which measured approximately 13 × 10 × 10 mm in length, width, and craniocaudal dimensions respectively. Subsequent PET scan demonstrated mild 18-FDG uptake within the nodule (maximum standard uptake value (SUV)=2.2, average liver SUV=2.5). Mild 18-FDG uptake was also demonstrated in borderline enlarged mediastinal and left hilar lymph nodes (maximum SUV=2.6). These lymph nodes demonstrated approximately 2 years of stability on the CT scan and were of uncertain significance. There were no other sites of abnormal 18-FDG uptake.

Management

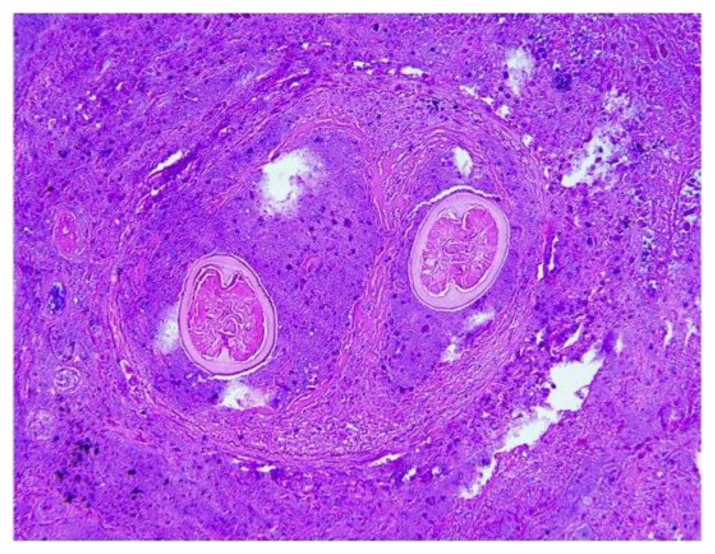

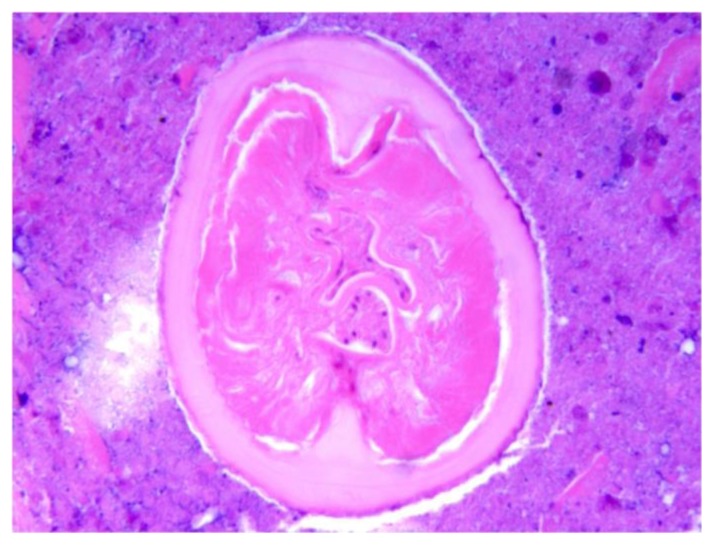

Although the lesion demonstrated only mild 18-FDG uptake on PET-CT, malignancy such as bronchioloalveolar cell carcinoma remained a consideration and the patient was referred to cardiothoracic surgery for further management. The patient underwent a wedge resection. Pathology revealed a discrete necrobiotic granulomatous nodule with a centrally placed thrombosed artery containing a parasitic worm (Figure 7). In cross section, the worm demonstrated internal longitudinal ridges and abundant somatic muscle, consistent with Dirofilaria immitis (Figures 8 and 9). The patient had an uneventful postoperative course and continued to be asymptomatic at follow up clinic visits.

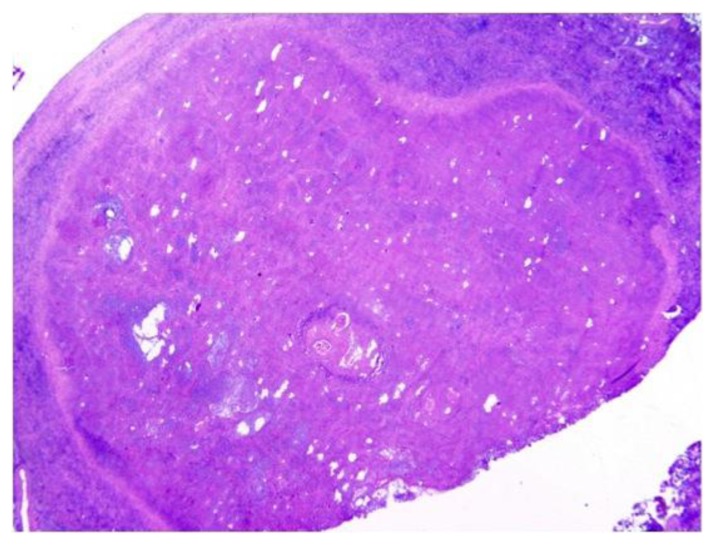

Figure 7.

57 year old male with pulmonary dirofilariasis.

Findings: Histopathology demonstrates a granulomatous reaction surrounding a centrally thrombosed artery.

Technique: Low power magnification, hematoxylin and esosin stain.

Figure 8.

57 year old male with pulmonary dirofilariasis.

Findings: Histopathology demonstrates an occluded pulmonary artery containing two cross sections of a filarial nematode.

Technique: 10X magnification, hematoxylin and esosin stain.

Figure 9.

57 year old male with pulmonary dirofilariasis.

Findings: Histopathology demonstrates a filaria in cross section with a multilayered culticle with an internal cuticular ridge and abundant somatic muscle, consistent with D. immitis.

Technique: 20X magnification, hematoxylin and esosin stain

DISCUSSION

Etiology & Demographics

Pulmonary dirofilariasis is a rare nonfatal disease caused by the filarial nematode Dirofilaria immitis, commonly known as the canine heartworm. The first case of pulmonary dirofilariasis in humans was reported in 1961 in a 57-year-old woman from Detroit, Michigan [1]. Since then, approximately 180 cases have been reported worldwide. The majority of cases have been in the southeastern United States [2]. The typical patient is a 40–60 year old male living in an area endemic for canine dirofilariasis. Reported cases have demonstrated an approximately 2:1 male to female incidence of disease [3].

D.immitis is a common canine parasite in many parts of the world. Other hosts include the cat, fox, muskrat, wolf, otter, and sea lion [4]. Mature adult worms form coiled masses in the right ventricle of definitive hosts. Female worms shed microfilariae, which circulate in the blood. These microfilariae can be transmitted to other hosts by many species of mosquitoes[5]. Humans are accidental hosts for D. immitis. The worm never reaches maturity. It dies and embolizes to the lung leading to pulmonary infarction. Although it is almost always a self-limited process that poses no significant health risk, its importance lies in its radiologic appearance, being potentially interpreted to represent metastatic or primary malignancy.

Clinical & Imaging Findings

Patients are most commonly asymptomatic. When symptomatic, common findings include cough, chest pain, eosinophilia, hemoptysis, and fever [6].

Typically, a single peripheral pulmonary nodule measuring 1 to 3 cm is identified on chest radiography or CT scan. Occasionally, patients can have bilateral and/or multiple nodules [6]. The lesions are typically smoothly marginated round or oval nodules with a predilection for the right lower lobe [7,8]. Our presented case is atypical in that the borders of the nodule were somewhat irregular. To our knowledge this has only been reported in one additional patient [9]. Oshiro and Moore have described contact with a feeding artery on CT scan [7,9]. This finding was demonstrated in our patient. 18-FDG uptake on PET scan is variable. Higashi et al. reported 3 cases that did not demonstrate 18-FDG uptake on PET scan [10]. As demonstrated in our reported case, the lesions in pulmonary dirofilariasis can demonstrate 18-FDG uptake. To our knowledge, only one prior case of 18-FDG uptake on PET scan has been reported in the literature [9]. In this prior case, 18-FDG avidity was significantly higher with SUV= 7.5 as compared to SUV=2.2 in our case. 18-FDG uptake likely reflects the granulomatous response to the parasite. We speculate that variability in 18-FDG uptake may relate to the timing of the initial insult, with higher activity reflecting a greater degree of active granulomatous inflammation.

Treatment & Prognosis

The lesions in pulmonary dirofilariasis pose no significant risk in asymptomatic patients. But as they typically raise concern for malignancy, they are usually resected. Diagnosis by fine needle aspiration is rare, but has been reported in two cases [6]. Given the lack of other sensitive or specific means of diagnosis, the lesions are typically excised.

Histopathologic examination demonstrates a central area of necrosis surrounded by a narrow granulomatous reaction. This necrotic zone is composed of epithelioid cells, plasma cells, lymphocytes, and occasional Langerhans or foreign body type granulomas. A single worm is typically found within a small artery in the necrotic tissue [4,6].

Following excision no further treatment is typically indicated. Should a reliable means of preoperative diagnosis be developed, surgery would likely not be indicated in most cases. In those cases where the diagnosis was obtained by fine needle aspiration, surgery was not performed [6].

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of a single pulmonary nodule on radiograph or CT is vast. Some considerations could include granuloma, bronchogenic carcinoma, hamartoma, metastatic disease, arteriovenous malformation (AVM), carcinoid, and round atelectasis.

On radiograph and CT a granuloma most commonly presents as a small calcified nodule. Laminar, central, or complete calcification may be seen. No discrete enhancement is typically seen on contrast enhanced CT. 18-FDG uptake can be variable on PET scan. An AVM typically presents as a peripheral 1–5 cm nodule or mass on radiograph or CT. Occasionally multiple lesions may be seen. The finding of feeding arteries and draining veins and avid enhancement is characteristic on CT. No discrete 18-FDG uptake is typically seen. On radiograph or CT, a bronchogenic carcinoma may appear as a spiculated or irregular nodule or mass. No discrete enhancement is typically seen on contrast enhanced CT. These lesions typically demonstrate 18-FDG uptake on PET scan, although a minor degree of uptake may be seen in bronchioloalveolar cell carcinoma. On radiograph and CT, hamartomas typically present as solitary smooth rounded nodules, occasionally with popcorn-like calcification. Internal fat density may be identified on CT. They may occasionally be endobronchial. Typically, no discrete 18-FDG uptake is seen. Pulmonary metastases usually present as multiple nodules or masses on radiograph or CT. A feeding vessel can occasionally be identified on CT in the setting of hematogenous metastases and enhancement on contrast enhanced CT is variable. 18-FDG uptake is typically seen on PET-CT. Carcinoid typically presents as a centrally located smooth round mass or nodule on radiograph or CT. Association with a main, lobar, or segmental bronchus is often identified on CT. Avid enhancement is typical on contrast enhanced CT. Typical carcinoids do not demonstrate discrete 18-FDG uptake. Round atelectasis most commonly appears on radiograph and CT as a subpleural rounded, irregular, or wedge shaped mass or nodule. Adjacent pleural thickening and volume loss are associated findings. On CT, convergence of bronchovascular structures with the lesion is typical. Air bronchograms may also be seen. These lesions typically enhance homogeneously on CT. No discrete 18-FDG uptake is typically seen on PET.

As discussed above, the differential considerations of a solitary pulmonary nodule on radiograph or CT are numerable. The finding of 18-FDG uptake on PET-CT would most often exclude the possibility of hamartoma, AVM, typical carcinoid, and round atelectasis. The remaining considerations can be further narrowed based on the clinical situation and additional imaging findings discussed above. Given that pulmonary dirofilariasis is usually not differentiated from malignancy, the diagnosis is typically made histopathologically.

TEACHING POINT

Pulmonary dirofilariasis typically presents as a smooth 1 to 3 cm rounded nodule in an asymptomatic patient. 18-FDG uptake on PET-CT is variable but the lesion may demonstrate increased uptake.

Table 1.

Summary table of pulmonary dirofilariasis.

| Etiology | Dirofilaria immitis |

| Incidence | Unknown, approximately 180 reported cases |

| Gender Ratio | Approximately 2 times more common in males |

| Age predilection | Most common between ages 40 and 60 |

| Risk factors | Residence in an area endemic for canine dirofilariasis |

| Treatment | Usually no treatment is necessary. Typically resected because of concern for malignancy |

| Prognosis | Excellent |

| Imaging Findings | Typically smooth rounded peripheral lung nodule. Most common in the right lower lobe. 18-FDG uptake can be seen on PET-CT. |

Table 2.

Differential diagnosis table for pulmonary dirofilariasis on radiograph, CT, and PET.

| Radiograph | CT | PET | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pulmonary Dirofilariasis |

|

|

|

| Arteriovenous Malformation |

|

|

|

| Primary Bronchogenic Carcinoma |

|

|

|

| Pulmonary Metastasis |

|

|

|

| Hamartoma |

|

|

|

| Typical Carcinoid |

|

|

|

| Round Atelectasis |

|

|

|

| Granuloma |

|

|

|

ABBREVIATIONS

- 18-FDG

18-Fluorodeoxyglucose

- CT

Computed Tomography

- PET

Positron Emission Tomography

- SUV

Standardized Uptake Value

REFERENCES

- 1.Dashiell G. A case of dirofilariasis involving the lung. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1961 Feb;10(1):37–8. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1961.10.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rena O, Leutner M, Casadio C. Human pulmonary dirofilariasis: uncommon cause of pulmonary coin-lesion. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2002 Jul;22(1):157–9. doi: 10.1016/s1010-7940(02)00221-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ciferri F. Human pulmonary dirofilariasis in the United States: a critical review. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1982 Mar;31(2):302–8. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1982.31.302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Neafie RC, Connor DH, Meyers WM. Dirofilariasis. In: Binford CH, Connor DH, editors. Pathology of tropical and extraordinary diseases. Armed Forces Institute of Pathology; Washington, DC: 1976. pp. 391–396. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ciferri F. Human pulmonary dirofilariasis in the West. West J Med. 1981 Feb;134(1):158–62. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Asimacopoulos P, Katras A, Christie B. Pulmonary dirofilariasis: the largest single hospital experience. Chest. 1992 Sep;102(3):851–55. doi: 10.1378/chest.102.3.851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Oshiro Y, Murayama S, Sunagawa U, et al. Pulmonary dirofilariasis: computed tomography findings and correlation with pathologic features. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2004 Nov-Dec;28(6):796–800. doi: 10.1097/00004728-200411000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Flieder DB, Moran CA. Pulmonary dirofilariasis: a clinicopathologic study of 41 lesions in 39 patients. Hum Pathol. 1999 Mar;30(3):251–6. doi: 10.1016/s0046-8177(99)90001-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moore W, Franceschi D. PET findings in pulmonary dirofilariasis. J Thorac Imaging. 2005 Nov;20(4):305–6. doi: 10.1097/01.rti.0000181524.95015.ea. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Higashi K, Ueda Y, Sakuma T, et al. Comparison of [(18)F]FDG PET and (201)Tl SPECT in evaluation of pulmonary nodules. J Nucl Med. 2001 Oct;42(10):1489–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]